The National Health Service (Procurement, patient choice and competition) Regulations 2013 is the statutory instrument which makes much more sense of the procurement regimen introduced previously. There is hardly any time to discuss the subtleties of this relatively short document which firmly thrusts the rules of the market in “competition” at the heart of NHS procurement. Many will say that these regulations existed in some form previously, but the legal intricacies of them definitely deserve full scrutiny. It sends CCGs into the coalface of making complicated procurement decisions, where the quality of tender might become significantly more important than actual “patient choice”. The procurement legislation as drafted could equally apply to procurement of virtually anything.

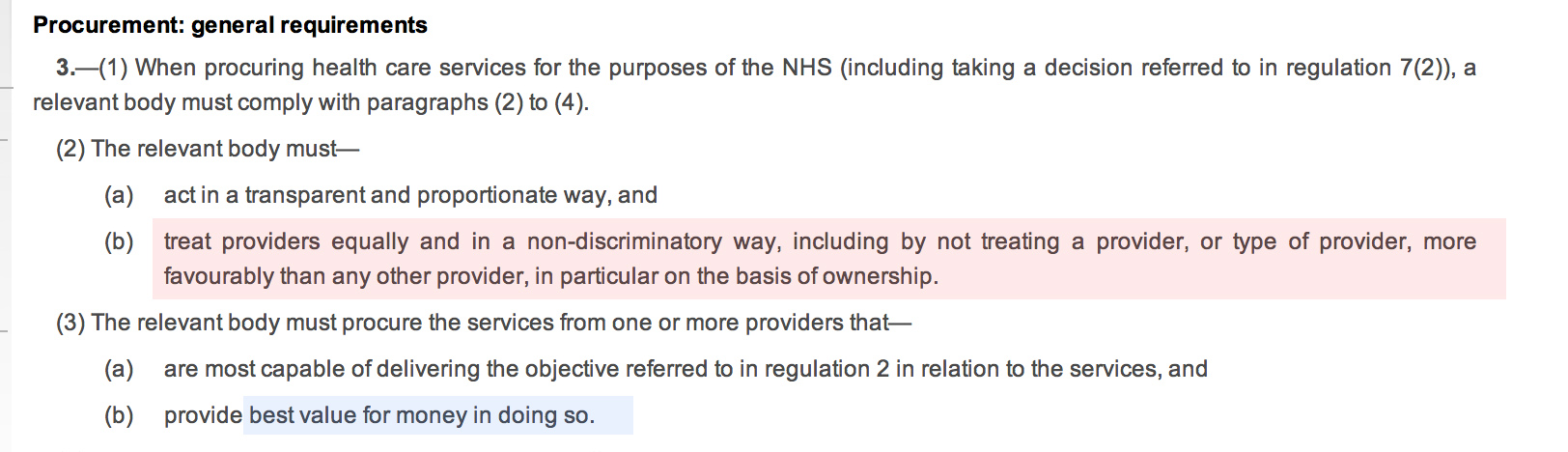

The entity, “the relevant body”, defined in s.1(2) as “CCG or board”, making the procurement decision according to s.3(2), and s.3(3) must make the procurement decision which does not favour any particular provider “in particular on the basis of ownership”, and which provides “best value”:

The inclusion of the reference to “ownership” is vague – it could possibly be a reference to not giving preference to NHS providers. The drafting of this Act voluntarily diminishes the rôle of the State in providing the NHS.

At first it seems that “best value” is simply to provide procurement at maximum “efficiency”, however it is widely acknowledged that there may be other benefits and outcomes of “best value” which might be hard to measure, e.g. effect locally on disadvantaged groups, possible local benefit in creating jobs. The notion of “best value” is indeed generally a thorny issue. The BIS document published in November 2011, entitled “Delivering best value through innovation: forward commitment procurement”, does however provide useful guidance. As an explanation of where it has come from, this guidance explains, “[this] comprises the European Union (EU) procurement directives, the EU Treaty principles of non-discrimination, equal-treatment and transparency, and the Governments procurement policy based on value for money”. However, the “best value” solution may not necessarily be the cheapest, and this is particularly relevant to innovative solutions (explained elsewhere in the document):

“Value for money should not be seen as a barrier to innovative solutions. Sometimes innovative offers can look more expensive in the short term, but will be a better offer in the long term. Although not listed explicitly in the Regulations, criteria involving innovative solutions may be used to determine the most economically advantageous tender, where they provide an economic advantage for the contracting authority which is linked to the product or service which is the subject matter of the contract.”

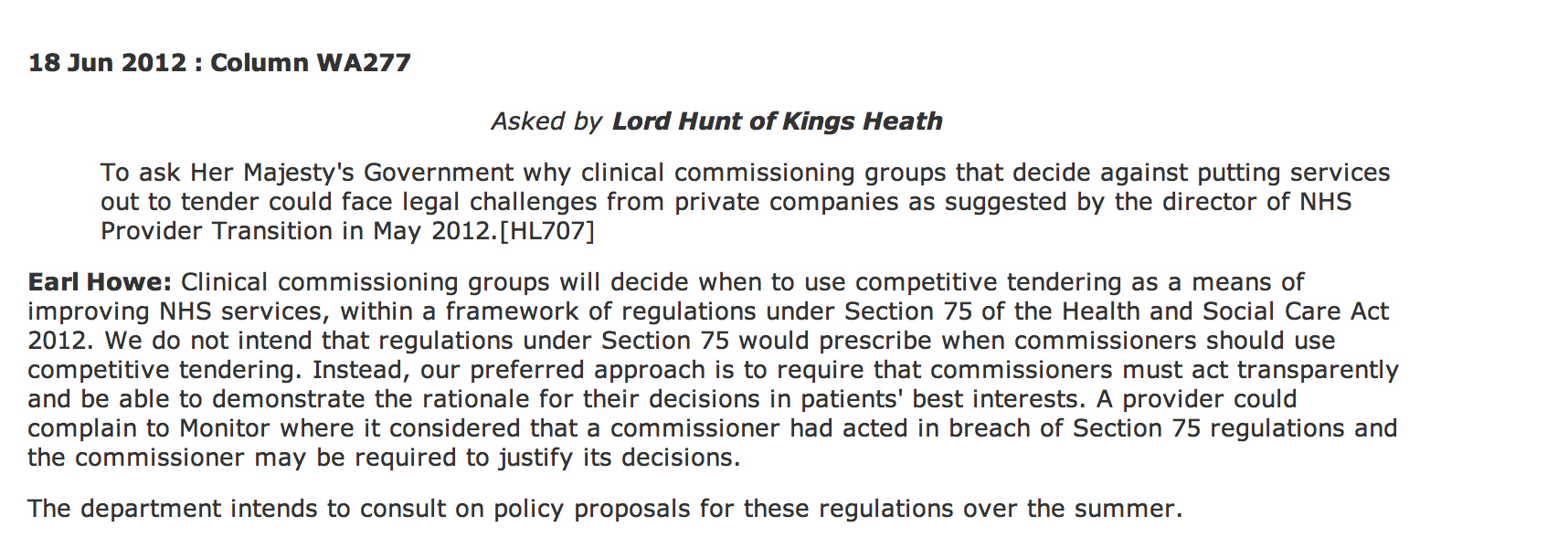

According to Hansard, Earl Howe did not intend to prescribe when ‘competitive tendering’ should exist under section 75 Health and Social Care Act (2012):

However, the problem is that Monitor can step in if the CCGs get the decision “wrong”.

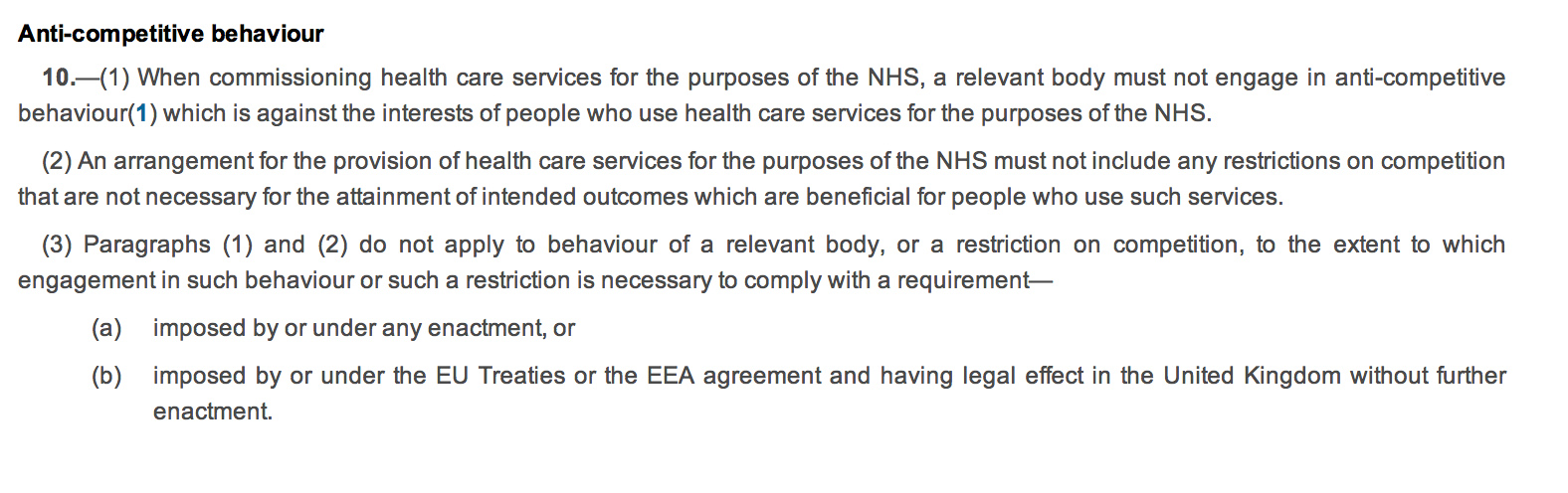

Regulation 10 governs the “anti-competitive principles”. The drafting of this is ‘clunky’, with 10(2) possibly the worst example of a double negative in drafting which offends the basic legal drafting principle of clarity. The Coalition has decided to enmesh the Act full-frontally in domestic and EU competition law (as shown in regulation 10(3)), whereas before there was a lifeline for escape from competition law because of the ambiguity in whether the terms “undertaking” or “economic activity” would apply to the NHS (a downloadable document is here). This is remarkable politically in that often governments describe the EU as imposing unnecessary legislation on UK citizens; here it is almost as if the Coalition is using EU arguments about general procurement law, applicable to widgets not clinical decision-making, to justify their NHS legislation. Again, a nuance in the drafting is clearly that a NHS provider cannot be given any preference in procurement. This reflects a notion in general procurement policy, of “equal treatment of providers”, designed to encourage confidence in the process and preventing abuse of the process for undue preference to any particular suppliers. Whilst this is an objective of the “UNICTRAL model law on the procurement of goods, construction and services” in the preamble, it is thought to be a subsidiary function, and is intended to protect against overt corruption and bribery.

It is an altogether different phenomenon if Parliament had intended to offer a “comprehensive”, nationally-planned health service, and therefore wished to have a corpus of NHS providers to fulfil this aim. There are no legal limitations on Parliament. It can pass any law whatsoever. The classic example (Sir Leslie Stephens, 1882) is that Parliament could pass a law ordering the death of all blue eyed babies.

It is an altogether different phenomenon if Parliament had intended to offer a “comprehensive”, nationally-planned health service, and therefore wished to have a corpus of NHS providers to fulfil this aim. There are no legal limitations on Parliament. It can pass any law whatsoever. The classic example (Sir Leslie Stephens, 1882) is that Parliament could pass a law ordering the death of all blue eyed babies.

It is left up to Monitor to “regulate” breaches of this statutory instrument (regulations 13-17). What is striking is that the legislation appears to suggest that all “complaints” are funneled through Monitor, rather than a general health ombudsman or judicial review (presumably CCGs are still public bodies serving a public function in the public interest). The system is therefore highly dependent on Monitor running a fully explicable process, and the statutory guidance on this will be critical. We have already seen this week the judiciary ‘clearing up’ bad law from parliament. The chances are that CCGs, without adequate legal advice, will end up being powerless in querying any decisions that Monitor has judged “incorrect”, which they are fully entitled to do of their own accord according to Regulation 13(2).

The legislation, whatever the intentions of the Conservatives, Liberal Democrats, or Labour, makes it much harder for the NHS to justify procurement from NHS providers without challenges, and whose side Monitor takes on these challenges is incredibly hard to predict because of the complexities in determining what is “best value”.