Home » Posts tagged 'patient choice'

Tag Archives: patient choice

National Health Service (Procurement, patient choice and competition) Regulations 2013: what is "best value"?

The National Health Service (Procurement, patient choice and competition) Regulations 2013 is the statutory instrument which makes much more sense of the procurement regimen introduced previously. There is hardly any time to discuss the subtleties of this relatively short document which firmly thrusts the rules of the market in “competition” at the heart of NHS procurement. Many will say that these regulations existed in some form previously, but the legal intricacies of them definitely deserve full scrutiny. It sends CCGs into the coalface of making complicated procurement decisions, where the quality of tender might become significantly more important than actual “patient choice”. The procurement legislation as drafted could equally apply to procurement of virtually anything.

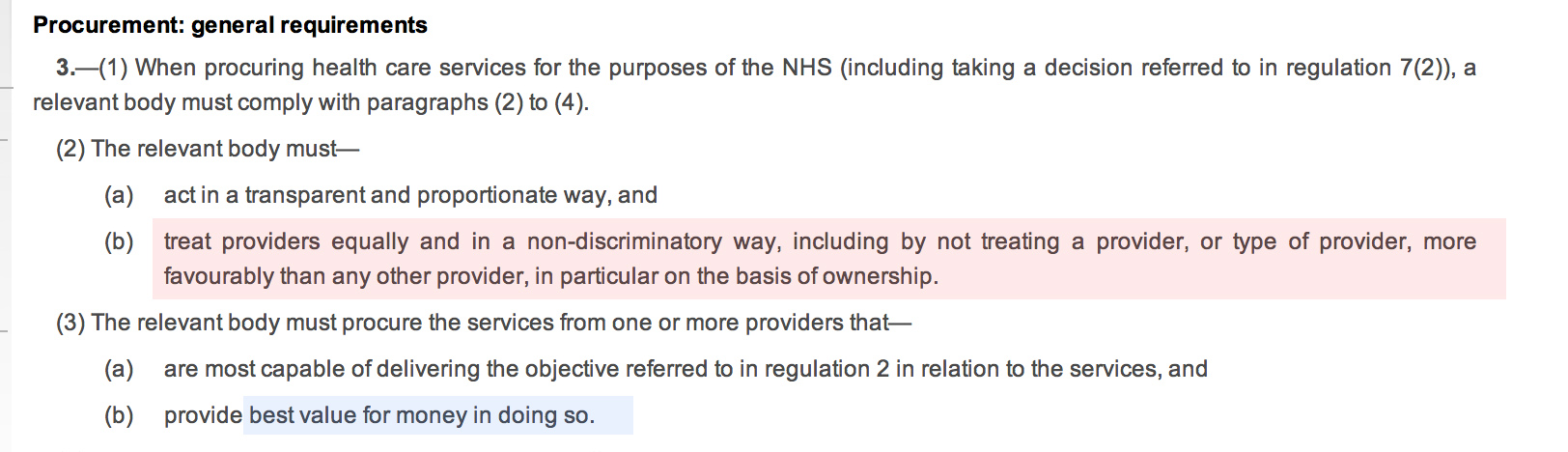

The entity, “the relevant body”, defined in s.1(2) as “CCG or board”, making the procurement decision according to s.3(2), and s.3(3) must make the procurement decision which does not favour any particular provider “in particular on the basis of ownership”, and which provides “best value”:

The inclusion of the reference to “ownership” is vague – it could possibly be a reference to not giving preference to NHS providers. The drafting of this Act voluntarily diminishes the rôle of the State in providing the NHS.

At first it seems that “best value” is simply to provide procurement at maximum “efficiency”, however it is widely acknowledged that there may be other benefits and outcomes of “best value” which might be hard to measure, e.g. effect locally on disadvantaged groups, possible local benefit in creating jobs. The notion of “best value” is indeed generally a thorny issue. The BIS document published in November 2011, entitled “Delivering best value through innovation: forward commitment procurement”, does however provide useful guidance. As an explanation of where it has come from, this guidance explains, “[this] comprises the European Union (EU) procurement directives, the EU Treaty principles of non-discrimination, equal-treatment and transparency, and the Governments procurement policy based on value for money”. However, the “best value” solution may not necessarily be the cheapest, and this is particularly relevant to innovative solutions (explained elsewhere in the document):

“Value for money should not be seen as a barrier to innovative solutions. Sometimes innovative offers can look more expensive in the short term, but will be a better offer in the long term. Although not listed explicitly in the Regulations, criteria involving innovative solutions may be used to determine the most economically advantageous tender, where they provide an economic advantage for the contracting authority which is linked to the product or service which is the subject matter of the contract.”

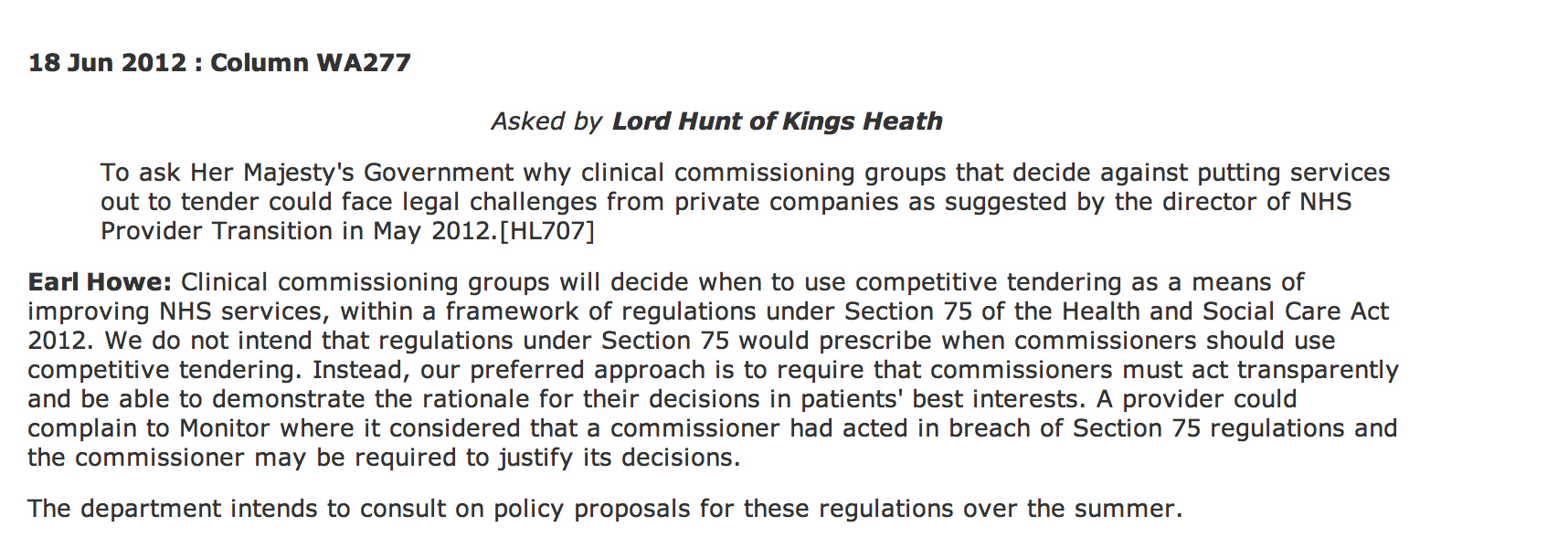

According to Hansard, Earl Howe did not intend to prescribe when ‘competitive tendering’ should exist under section 75 Health and Social Care Act (2012):

However, the problem is that Monitor can step in if the CCGs get the decision “wrong”.

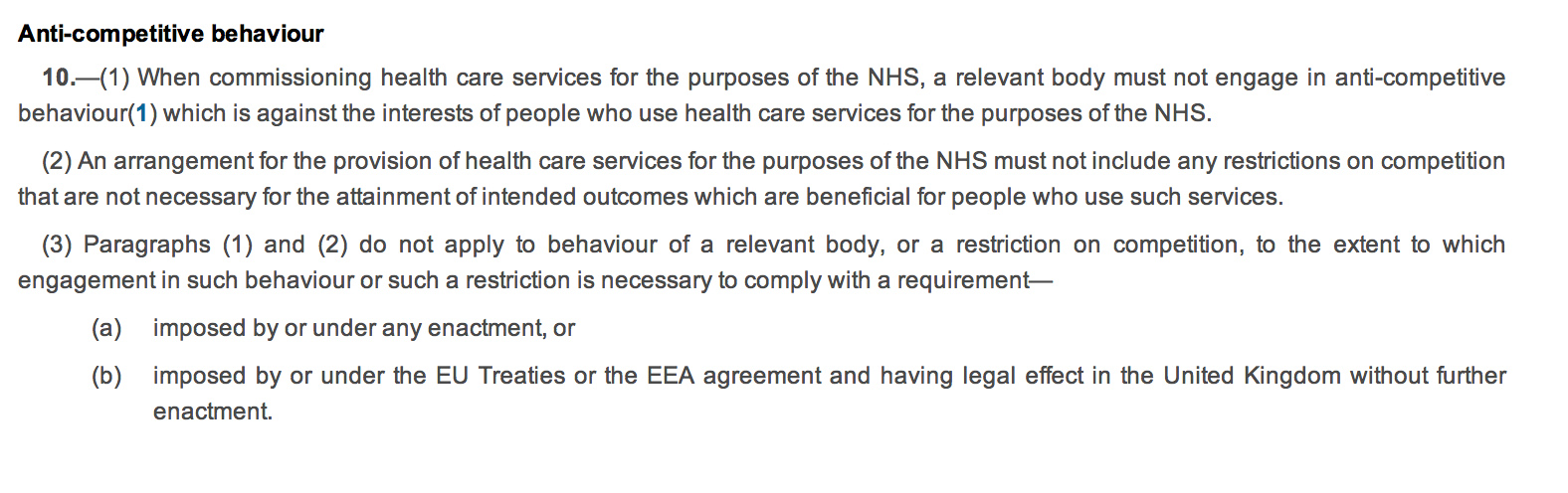

Regulation 10 governs the “anti-competitive principles”. The drafting of this is ‘clunky’, with 10(2) possibly the worst example of a double negative in drafting which offends the basic legal drafting principle of clarity. The Coalition has decided to enmesh the Act full-frontally in domestic and EU competition law (as shown in regulation 10(3)), whereas before there was a lifeline for escape from competition law because of the ambiguity in whether the terms “undertaking” or “economic activity” would apply to the NHS (a downloadable document is here). This is remarkable politically in that often governments describe the EU as imposing unnecessary legislation on UK citizens; here it is almost as if the Coalition is using EU arguments about general procurement law, applicable to widgets not clinical decision-making, to justify their NHS legislation. Again, a nuance in the drafting is clearly that a NHS provider cannot be given any preference in procurement. This reflects a notion in general procurement policy, of “equal treatment of providers”, designed to encourage confidence in the process and preventing abuse of the process for undue preference to any particular suppliers. Whilst this is an objective of the “UNICTRAL model law on the procurement of goods, construction and services” in the preamble, it is thought to be a subsidiary function, and is intended to protect against overt corruption and bribery.

It is an altogether different phenomenon if Parliament had intended to offer a “comprehensive”, nationally-planned health service, and therefore wished to have a corpus of NHS providers to fulfil this aim. There are no legal limitations on Parliament. It can pass any law whatsoever. The classic example (Sir Leslie Stephens, 1882) is that Parliament could pass a law ordering the death of all blue eyed babies.

It is an altogether different phenomenon if Parliament had intended to offer a “comprehensive”, nationally-planned health service, and therefore wished to have a corpus of NHS providers to fulfil this aim. There are no legal limitations on Parliament. It can pass any law whatsoever. The classic example (Sir Leslie Stephens, 1882) is that Parliament could pass a law ordering the death of all blue eyed babies.

It is left up to Monitor to “regulate” breaches of this statutory instrument (regulations 13-17). What is striking is that the legislation appears to suggest that all “complaints” are funneled through Monitor, rather than a general health ombudsman or judicial review (presumably CCGs are still public bodies serving a public function in the public interest). The system is therefore highly dependent on Monitor running a fully explicable process, and the statutory guidance on this will be critical. We have already seen this week the judiciary ‘clearing up’ bad law from parliament. The chances are that CCGs, without adequate legal advice, will end up being powerless in querying any decisions that Monitor has judged “incorrect”, which they are fully entitled to do of their own accord according to Regulation 13(2).

The legislation, whatever the intentions of the Conservatives, Liberal Democrats, or Labour, makes it much harder for the NHS to justify procurement from NHS providers without challenges, and whose side Monitor takes on these challenges is incredibly hard to predict because of the complexities in determining what is “best value”.

Information imbalances are the heart of many recent disasters

Had certain people at the BBC known about, and acted upon, the information which is alleged about Jimmy Savile, might things have turned out differently? George Entwhistle tried to explain yesterday in the DCMS Select Committee his local audit trail of what exactly had happened with the non-report by Newsnight over these allegations.

‘Information asymmetry’ deals with the study of decisions in transactions where one party has more or better information than the other. This creates an imbalance of power in transactions which can sometimes cause the transactions to go awry, a kind of market failure in the worst case. Information asymmetry causes misinforming and is essential in every communication process. In 2001, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to George Akerlof, Michael Spence, and Joseph E. Stiglitz for their “analyses of markets with asymmetric information.” Information asymmetry models assume that at least one party to a transaction has relevant information whereas the other(s) do not. Some asymmetric information models can also be used in situations where at least one party can enforce, or effectively retaliate for breaches of, certain parts of an agreement whereas the other(s) cannot.

In adverse selection models, the ignorant party lacks information while negotiating an agreed understanding of or contract to the transaction, whereas in moral hazard the ignorant party lacks information about performance of the agreed-upon transaction or lacks the ability to retaliate for a breach of the agreement. An example of adverse selection is when people who are high risk are more likely to buy insurance, because the insurance company cannot effectively discriminate against them, usually due to lack of information about the particular individual’s risk but also sometimes by force of law or other constraints. An example of moral hazard is when people are more likely to behave recklessly after becoming insured, either because the insurer cannot observe this behavior or cannot effectively retaliate against it, for example by failing to renew the insurance.

Joseph E. Stiglitz pioneered the theory of screening, and screening is a pivotal theme in both economics and medicine. In this way the underinformed party can induce the other party to reveal their information. They can provide a menu of choices in such a way that the choice depends on the private information of the other party.

Examples of situations where the seller usually has better information than the buyer are numerous but include used-car salespeople, mortgage brokers and loan originators, stockbrokers and real estate agents. Examples of situations where the buyer usually has better information than the seller include estate sales as specified in a last will and testament, life insurance, or sales of old art pieces without prior professional assessment of their value.

This situation was first described by Kenneth J. Arrow in an article on health care in 1963. The asymmetry of information makes the relationship between patients and doctors rather different from the usual relationship between buyers and sellers. We rely upon our doctor to act in our best interests, to act as our agent. This means we are expecting our doctor to divide herself in half – on the one hand to act in our interests as the buyer of health care for us but on the other to act in her own interests as the seller of health care. In a free market situation where the doctor is primarily motivated by the profit motive, the possibility exists for doctors to exploit patients by advising more treatment to be purchased than is necessary – supplier induced demand. Traditionally, doctors’ behaviour has been controlled by a professional code and a system of licensure. In other words people can only work as doctors provided they are licensed and this in turn depends upon their acceptance of a code which makes the obligations of being an agent explicit or as Kenneth Arrow put it “The control that is exercised ordinarily by informed buyers is replaced by internalised values”

In standard civil litigation, disclosure of information takes place between the two parties in standard proceedings, a party must disclose every document of which it has control and which falls within the scope of the court’s order for disclosure. Even if a party discloses a document, the other party is not entitled to inspect the document. Of course, this disclosure procedure might have effects in producing information imbalances, where it is important to see ‘the big picture’. Such a situation is the Leveson Inquiry, ultimately looking at how activities might be better regulated if appropriate (and by whom). The communications with the former News International chief executive and the News of the World editor-turned spin doctor, Andy Coulson, were reportedly kept from the hearings into press standards after the Prime Minister sought legal advice. Labour said that David Cameron, the UK Prime Minister, must make sure that “every single communication” that passed between him and the pair be made available to the inquiry and the public. The cache runs to dozens of emails including messages sent to Mr Coulson while he was still an employee of Rupert Murdoch, according to reports. It was described by sources as containing “embarrassing” exchanges with the potential to cast further light on Mr Cameron’s relationship with two of Mr Murdoch’s most senior executives. However, Downing Street was said to have been advised that it was not “relevant” to the Leveson inquiry as the documents they contained fell outside its remit, according to The Independent.

Information imbalances, for us on a more daily basis, have a direct effect on the consumer-supplier relationship of the econy, We have been told to absurdity on how much of our problems as consumers would be solved if we could simply ‘switch easily’ between energy suppliers. In a sense, either there should be far less competition (i.e. the whole thing merges into one state supplier, reducing absurdities in a few suppliers all providing the same product at a high price, similar to exam boards currently), or there should be far more competition (there is currently an oligopolistic situation in many markets, which would be greatly ameliorated by having many more active participants in the competition market.) In 2009, the four largest banks supplied 67% of the market of mortgages, and, in 2006, the ‘big four’ banks accounted for 47% of the market. According to the “Cruickshank review”, the ‘big four’ banks accounted for 17% of the market. Demutualised building societies held 48%: these are, (a) Lloyds TSB, Halifax and Bank of Scotland; (b) Royal Bank of Scotland, Natwest; (c) HSBC, First Direct; (d) Abbey, Alliance and Leicester, Bradford and Bingley.

The Competition Commission believes that helping customers to easily switch products is paramount to the effective operation of competitive markets: markets do not function without customers who vote with their feet. As Dr Adam Marshall of the British Chambers of Commerce told the Commission: ‘There’s lots of products and services on the market, but the theoretical competition between those products and services is limited by the real world barriers of form filling, hassle, bureaucracy, decisions not being taken, etc…’ The regulator responsible for consumer protection regulation should have both: (a) an explicit mandate to promote effective competition in markets in the financial sector; and (b) the necessary powers to regulate the sector to achieve this, including the ability to apply specific licence conditions to banks and exercise competition and consumer protection legislation. These powers will be concurrent with the competition powers of the OFT, and will enable the regulator to both enforce competition law and make market investigation references to the Competition Commission.

The aim of consumer protection regulation is to promote the conditions under which effective competition can flourish as far as possible, and where not, the regulator will be able to take direct action. In order best to promote the interests of the consumer, the regulator will encourage financial firms to compete: on the merit of the quality and price of their products and services; and to gain a competitive advantage by investment in innovation, technology, operational efficiency, superior products, superior service, due diligence, human capital, and offering better information to customers. Ideally, the regulator would then step in whenever there is a sign of market failure. Market failures include: (a) poor quality information being disclosed to consumers when they are deciding whether to purchase products; (b) information asymmetry between the provider and the consumer; or (c) providers taking advantage of typical consumer behaviour such as the tendency evident in retail customers to select the default option offered, and reluctance to switch products because of inertia. Any sign of market failure indicates that competition is probably not effective, and the regulator should then take action to counteract the failure.

Therefore, it is hard to see how information imbalances are not at the heart of many ‘decisions’ affecting modern life, and can lead to imperfect decisions being made. Ideally, it is up to parties to make a full disclosure about things, whether this includes personal health or corporate misfeasance; if they are not so willing to give up their secrets, they possibly can be ‘nudged’ into doing so. Of course, some parties, particularly those intending to generate a healthy shareholder dividend, may not be very keen at all at spilling the beans, and that is where law and regulation come in. However, even then there can be significant imbalances in the legal process which can be obstructive in the correct solutions being arrived at. Certainly the field has progressed substantially since this Nobel Prize for Economics was first awarded over 30 years ago.

Patient choice (yet again)

In a brief blogpost on ‘patient choice’, it’s hard to do anything really innovative like adding 2 and 2 to make 5. ‘Patient choice’ has been a game of ping-pong for the Conservatives and Labour, as this hot potato has been thrown around by Andy Burnham, Pat Hewitt, Alan Milburn, Andrew Lansley, and many others. They won’t be the first or the last.

Often the Annual Report is a dry statement of a state of affairs. Used creatively, it can be an ambitious marketing document. For example, in their Annual Report (downloadable here), Circle of Hinchinbrooke fame, refers to “significant gains in the number of patients being offered choice, …”, and then, “Firstly, we referred the issue of consultants’ contracted hours to the NHS Co-operation and Competition Panel (‘CCP’) which accepted our argument that consultants should have the freedom to practice at the location of their patients’ choice.” And then – “Secondly, we referred Primary Care Trusts (‘PCT’s) that were restricting NHS patients’ choice to the CCP, which again ruled in favour of patient choice.” Circle quickly pop it in then in the context of “Extended Choice Network”. Andy Burnham, back in 2006, in an extensive report on choice, explained that, for the public, “patients want and value choice: evidence from pilots, patient and public surveys and focus groups has shown this. Indeed, in 2007, Patricia Hewitt unveiled, “[a] new Choice website will allow members of the public and clinicians to access a range of information through one super site that will act as a one-stop gateway to navigate NHS services.”

There is a backdrop of Labour, through Alan Milburn, rejecting an ‘overcentralised State’, and Andy Burnham, while being fundamentally proud of NHS values, advocating de-centralised Foundation Hospitals. Given that this concept is being used by all parties, socialists have a different political definition of ‘choice’ compared to others such as libertarians. Socialists believe in sharing risks in society, where there aren’t winners or losers; this is why philosophically libertarianism is so difficult to reconcile with utilitiarianism (maximum benefit for all, amongst other things).

Having started with marketing and philosophy above, there are critical other aspects to this ‘choice’ debate from different academic disciplines, I feel:

1. Economics. (a) Patricia Hewitt’s website only works on complete, high-quality information. With people not disclosing full information because of patchy coverage nationally, ‘moral hazard‘ may occur where one party carries the risk for another party’s lack of provision of information. Corporates will have to be mandated to disclose all their results, including less impressive health outcomes. (b) The market will be oligopolistic, with some suppliers preferring not to participate in certain unprofitable markets, like dementia, meaning the ability to maximise shareholder dividend, with venture capital backing, in an uncompetitive market quite likely.

2. Accounting. The cost of collecting statistics, many of which can be irrelevant, needs resources, and can be expensive. This is for example the reason why some companies, unless they are large, do not collect metrics about activity in costing their business activities (“activity based costing”, as this is far too costly potentially) Who’s going to decide what information to collect and who’s going to collect this information in a small GP surgery or DGH?

3. Medicine. Quality healthcare depends not only on systems being in place for healthcare such as patient safety, but fundamentally depends on the quality of the physician and GP. For example, a provisional diagnosis of pneumocystis carinii can be made in A&E by a simple device that measures oxygen plummeting on somebody climbing a flight-of-stairs. It doesn’t need a multi-million £ CT machine, with costs transferred to the patient aka customer, and even the chest x-ray might be unhelpful.

4. Law. Choice is well known to the lawyers in the guise of competition. The regulatory mechanism is clearly inadequate in the new Health and Social Care Act. Agreements between competitors setting their prices collectively, price-fixing or abuse of dominant position would be clearly illegal under UK or European Competition Law, thankfully.

5. Ability of a patient to act on the information. Ultimately the patient is not specialist enough to choose between hospital suppliers anyway, and may not be able to implement his/her choice easily (unless the Government chooses to allow more ill patients greater personalised budgets, or travel expenses for travelling to distant units).

Either way, the NHS has now embarked on an experiment which it seems it cannot reverse, and which has not been mandated by any voter. It has been entirely enabled by the Liberal Democrats. The Socialist Health Association should explain why the socialist model does not throw up these problems, because ultimately we want an excellent service for everyone, irrespective of state-of-health or ability-to-pay.