Home » Posts tagged 'regulations'

Tag Archives: regulations

The section 75 NHS regulations exposed muddled thinking all round; but is there really no alternative?

It’s easy to lose sight of Labour’s fundamental question in terms of the economic model; viz, whether the State should, in fact, intervene in any failing #NHS healthcare (in a financial sense). That is what distinguishes it from neoliberal models of healthcare, including the New Labour one. It is a reasonable expectation that the healthcare regulators will uphold professional standards of the medical and nursing professions, whether in the public or private sector.

One of the most memorable experiences in my whole journey of the section 75 NHS regulations was Richard Bourne, the Chair of the Socialist Health Association, asking me what would probably happen at the end of the day. I originally replied saying that I was not an astrologer, but, as I thought about that question more, I became totally convinced it was a very reasonable question to ask. In management, private or public, when one is uncertain about the outcome, a perfectly valid tool is the ‘scenario analysis’, where one considers the various options and their likelihood of success. Also, if you really don’t know what the eventual outcome is, which might be the case, say, if you have to produce a complicated budget for the whole of the next year, you can to some extent ‘hedge your bets’ by doing a rolling forecast which updates your plan on the basis of virtually contemporaneous information.

Section 75 NHS regulations had become a very ‘Marmite issue’. Richard was right to pick up on the fact that the world would not necessarily implode with the successful resolution by the House of Lords of the second version of the regulations. On the other hand, the event itself marked a useful occasion for us all to take stock of where the overall ‘direction of travel’ was heading. Wednesday’s charge, led by Lord Phil Hunt, was as ‘good as it gets’. Reasons for why Labour in places produced a lack lustre attack is that some individuals themselves were alleged to have significant conflicts of interest, or some elderly Peers were unable to organise suitable accommodation so that they could negotiate the ‘late night’ vote. Lord Walton of Detchant, whom all junior neurologists will have encountered in their travels at some point in the UK, said convincingly he had a look at the Regulations, and felt that they would be OK even given the ‘torrent’ of communication he had personally received about it.

I certainly don’t wish to rehearse yet again the arguments for why the section 75 NHS regulations appears to be farming out the NHS to the private sector, but in the 1997 Labour manifesto, where Tony Blair was likely to win, Labour promised to abolish the purchaser-provider split. It didn’t. Labour likewise is promising now the repeal the current reincarnation of the Health and Social Care Act. It might not. There is substantial brand loyalty to Labour, over the NHS, such that the Conservatives would find it hard to emulate the goodwill of the public towards it that is shown to Labour. Given that the market has been implemented in the NHS, the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats are now arguing that they wish to make the market ‘a fair playing field’, which is of course a reasonable aspiration provided that a comprehensive NHS can be maintained for the public good.

Many have no fundamental objection to running a NHS most efficiently. I often find that health policy experts who have little clinical knowledge find themselves going on wild goose chases about efficiency in the NHS. For example, I remember the biggest barrier to progressing with a patient with an acute coronary syndrome is that it would be impossible to get a troponin blood result off the HISS computer system for hours, such that you would be forced to track somebody down from the laboratory itself. Co-ordinated care can mean better care. The best example I can think of is where a GP prescribes Viagra for a man with erectile problems in the morning, the patient collects all his new medication from the local chemist, the patient then takes the first tablet around lunchtime, the patient has sex with his partner in the evening, but unfortunately attends A&E in the evening for angina (chest pain). Modern advice (for example here) would argue that an emergency room should take a very cautious approach in administering nitrates, a first line medication for angina, within 24 hours of a dose of viagra. What a Doctor would do in this particular scenario is not something I wish to discuss, but it is simply to demonstrate that patient care would benefit from ‘joined up’ operational processes, where the emergency room doctor had knowledge of what had been prescribed etc. that day.

So, it probably was no wonder that there was ‘muddled thinking’ all round. Baroness Williams is a case in point. She acknowledges that many in the social media think that she personally, with the Liberal Democrats en masse, has ‘sold out’ on the NHS. And yet she talks about a deluge of misinformation from organisations such as 38 degrees who cannot be shot for being the messenger for a concerned public; that presumably is consistent with the Liberal Democrats yearning for ‘a fair society’? Lord Clement-Jones attacked the person not the ball, advancing the argument that lawyers will always provide a legal opinion which favours the client. However, many agree with David Lock QC in his concerns on how the legislation could be interpreted to go further than the previously existant legislation from Labour over the Competition and Cooperation Panel. Indeed, Labour in the late 2000s had tried to legislate for public contracts, with attention to how their statutory instruments might be consistent with EU competition law.

However, the muddled thinking did not stop there. Only a few people consistently explained why the regulations were a ‘step too far’, and it is no small achievement that the original set of regulations had to be abandoned. The general public themselves can be legitimately blamed for muddled thinking. The general impression is that they resent bankers being awarded bonuses, resent the explosion of the deficit due to the banking crisis, but did not wish the banks to implode. The general impression is also they are happy with the previously high satisfaction ratings of the NHS, do not wish the NHS budget to be cut, and yet do not want ‘failing NHS trusts’ to be shut down altogether. Meanwhile, the Francis report exposed sheer horror in how some patients and their relatives or families experienced care from the NHS, and there are concerns that similar phenomena might be exposed in other Trusts. All of this is totally cognitively dissonant with the idea of ‘efficiency savings’ in the NHS, with billions of surplus being given back to the Treasury instead of frontline patient care. The issue about whether private companies should be allowed to make a profit from healthcare is a difficult one, when compared to an issue of whether parents can have a ‘choice’ as to whether to send their children to independent schools. However, many members of the general public would prefer any profit made in the NHS to be put back into patient care, rather than lining the pockets of shareholders or producing healthy balance sheets of private equity investors. The section 75 NHS regulations has done nothing for a discussion about how to maximise patient safety, nor the value of employees in the NHS. Managers in the NHS appear to be pre-occupied with ‘excellence awards’, innovation and leadership, but appear to have lost sight of the big picture of the real distress shown by some working at the coal face in the NHS.

Monitor, the new economics healthcare regulator, has a pivotal part to play; but they are an economic regulator ensuring fair competition, so it is hard to see as yet how they can best secure value for the patient rather than dividend for the providers. This is a Circle to be squared (pardon the pun). Possibly the only way to ensure that the NHS does not become a ‘race to the bottom’ (where “I don’t care who provides my healthcare as long as it’s the most efficient” becomes “I don’t care who provides my healthcare as long as it’s the cheapest and delivers most profit for the private provider)” is to ensure that people who are clinically skilled are involved in procurement decisions, or in regulatory decisions. This is the only way where yet another one of Earl Howe’s promises might be fulfilled; that local commissioners can commission services, even if they are only available from the NHS, if it happens that ‘there is no alternative’. Possibly doom-and-gloom is not needed yet, but it cannot be said that Lord Warner did much to inspire faith as the only Labour peer to vote against Labour’s “fatal motion”. Many people did indeed share the sense of despair felt by Lord Owen before, during and after the debate. However, Labour has to react to the present and think about the future. It cannot rewind much of the past, for example current PFI contracts in progress. The public have already exhausted themselves with the debate over ‘who is to blame over PFI?’, where both Labour and Conservatives have contributed in different ways to the implementation of PFI, and there are still some who believe that the benefits of infrastructure spending through PFI are yet to be seen. But blaming people now is probably a poor way to use precious resources, and there is a sense of ‘in moving forward, I wouldn’t start from here.’ Labour has to think now carefully of what exactly it is that it intends to repeal and reverse. Its fundamental problem, apart from sustainability, is to what extent the State should ‘bail out’ parts of the system which, for whatever reason, aren’t working; but this is essentially the heart of the neoliberal v socialism debate, without using such loaded language?

Shibley tweets at @legalaware.

How is parliamentary procedure being followed to take the previous statutory instrument on NHS procurement out-of-action?

A Statutory Instrument is used when an Act of Parliament passed after 1947 confers a power to make, confirm or approve delegated legislation on: the Queen and states that it is to be exercisable by Order in Council; or a Minister of the Crown and states that it is to be exercisable by Statutory Instrument. 1.15 pm last Tuesday (5 March 2013) saw Andy Burnham MP, the Shadow Secretary of State for Health, go head-to-head with Norman Lamb (The Minister of State, Department of Health). Lamb was invited to comment on the regulations on procurement, patient choice and competition under section 75 of the Health and Social Care Act 2012.

The discussion is reported in Hansard.

Lamb describes an intention to ‘amend’ the legislation

Lamb explains:

“Concerns have been raised that Monitor would use the regulations to force commissioners to tender competitively. However, I recognise that the wording of the regulations has created uncertainty, so we will amend them to put this beyond doubt.”

The problem is that this statutory instrument would have become law automatically on 1 April 2013, and still promises to do so in the absence of anything else happening. The safest way to get this statutory instrument out-of-action is to ‘annul’ the law, rather than having the statutory instrument still in force but awaiting amendment. Experts are uncertain the extent to which statutory instruments can be so easily amended, while in force.

Most Statutory Instruments (SIs) are subject to one of two forms of control by Parliament, depending on what is specified in the parent Act.

Fatal motion

There is a constitutional convention that the House of Lords does not vote against delegated legislation. However, Andy Burnham has said the exceptional nature of the Section 75 regulations, which force all NHS services out to tender, meant he needed to table a ‘fatal’ motion in the second Chamber. Indeed, Lord Hunt later tweeted that this fatal chamber had forced a rethink on the original Regulations:

The main effect of delegated legislation being made by Statutory Instrument is that it is effective as soon as it is made, numbered, catalogued, printed, made available for sale, and published on the internet. This ensures that the public has easy access to the new laws. This statutory instrument (SI 2013/057:The National Health Service (Procurement, Patient Choice and Competition) Regulations 2013) is still available in its original form, with no declaration of its imminent amendment or annulment, on the official legislation website here.

The “Prayer”

The more common form of control is the ‘negative resolution procedure’. This requires that either the Instrument is laid before Parliament in draft, and can be made once 40 days (excluding any time during which Parliament is dissolved or prorogued, or during which both Houses are adjourned for more than four days) have passed unless either House passes a resolution disapproving it, or the Instrument is laid before Parliament after it is made (but before it comes into force), but will be revoked if either House passes a resolution annulling it within 40 days.

A motion to annul a Statutory Instrument is known as a ‘prayer’ and uses the following wording:

- That an humble address be presented to Her Majesty praying that the [name of Statutory Instrument] be annulled.

Any member of either House can put down a motion that an Instrument should be annulled, although in the Commons unless the motion is signed by a large number of Members, or is moved by the official Opposition, it is unlikely to be debated, and in the Lords they are seldom actually voted upon.

Indeed, this is exactly what happened. Ed Miliband submitted EDM 1104 on 26 February 2013, which currently – at the time of writing – has 183 signatures – with the exact wording:

“That an humble Address be presented to Her Majesty, praying that the National Health Service (Procurement, Patient Choice and Competition) Regulations 2013 (S.I., 2013, No. 257), dated 11 February 2013, a copy of which was laid before this House on 13 February, be annulled.”

The purpose of “amending” the legislation

Lamb later provides in his answer:

“Concerns have also been raised that competition would be allowed to trump integration and co-operation. The Future Forum recognised that competition and integration are not mutually exclusive. Competition, as the Government made clear during the passage of the Bill, can only be a means to improve services for patients—not an end in itself. What is important is what is in patients’ best interests. Where there is co-operation and integration, there would be nothing in the regulations to prevent this. Integration is a key tool that commissioners are under a duty to use to improve services for patients. We will amend the regulations to make that point absolutely clear.”

How the Government “amends” the legislation is clearly pivotal here. Integration is another “buzzword” in the privatisation ammunition. Colin Leys wrote in 2011:

“In the emerging vision of the Department of Health, however, integrated care has always been associated with the drive to enlarge private sector provision, and the Kaiser [Permanente] connection emphasised this. The competitive culture attached to integrated care in the Kaiser model, coupled with the keen interest of private providers in all integrated care initiatives, were constants, and put their stamp on official thinking about the future NHS market.”

A possible reason for why this emphasis on competition has failed is that in other markets, such as utilities, rail and telecoms, there is a strong case that competition has not driven down cost at all, because of shareholder dividend primacy. Another good reason for people in favour of the private market to discourage competition is that competition might even inhibit a drive to integration, and integration is strongly promoted by private providers (and, incidentally, New Labour).

What does the Act itself say about ‘annulling’ statutory instruments?

According to s. 304(3), “Subject to subsections (4) to (6), a statutory instrument containing regulations under this Act, or an order by the Secretary of State or the Privy Council under this Act, is subject to annulment in pursuance of a resolution of either House of Parliament.” So, at the moment, we are clearly in limbo, with parliament yet to pass a EDM, and new redrafted Regulations yet to appear. However, it is still a very dangerous situation, as the original set of Regulations is still yet to be enacted on 1 April 2013.

National Health Service (Procurement, patient choice and competition) Regulations 2013: what is "best value"?

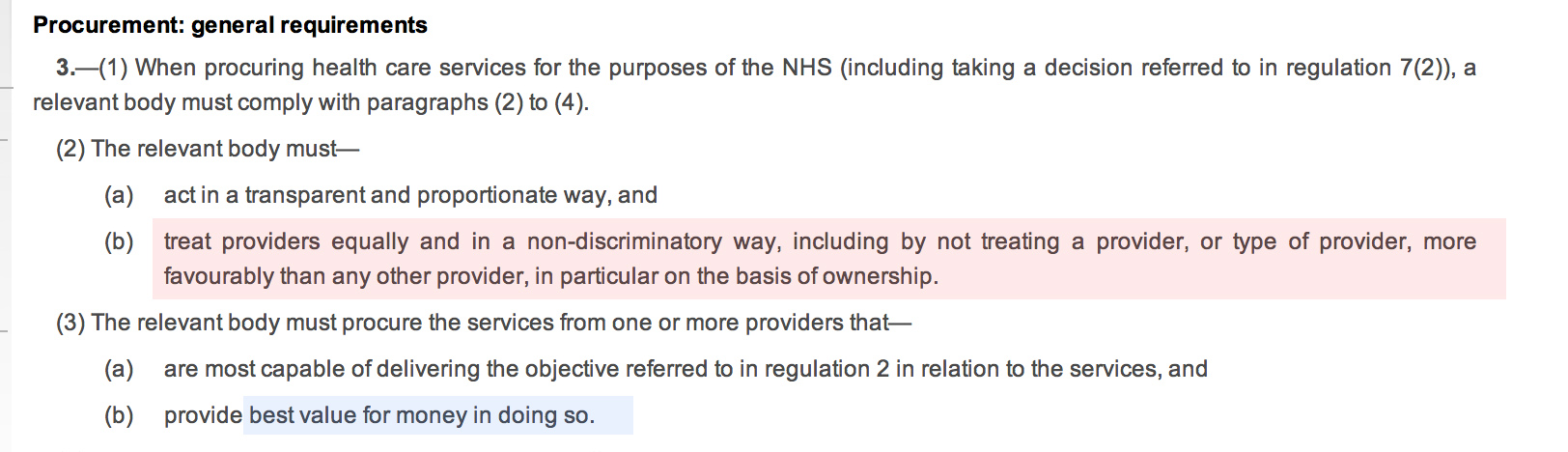

The National Health Service (Procurement, patient choice and competition) Regulations 2013 is the statutory instrument which makes much more sense of the procurement regimen introduced previously. There is hardly any time to discuss the subtleties of this relatively short document which firmly thrusts the rules of the market in “competition” at the heart of NHS procurement. Many will say that these regulations existed in some form previously, but the legal intricacies of them definitely deserve full scrutiny. It sends CCGs into the coalface of making complicated procurement decisions, where the quality of tender might become significantly more important than actual “patient choice”. The procurement legislation as drafted could equally apply to procurement of virtually anything.

The entity, “the relevant body”, defined in s.1(2) as “CCG or board”, making the procurement decision according to s.3(2), and s.3(3) must make the procurement decision which does not favour any particular provider “in particular on the basis of ownership”, and which provides “best value”:

The inclusion of the reference to “ownership” is vague – it could possibly be a reference to not giving preference to NHS providers. The drafting of this Act voluntarily diminishes the rôle of the State in providing the NHS.

At first it seems that “best value” is simply to provide procurement at maximum “efficiency”, however it is widely acknowledged that there may be other benefits and outcomes of “best value” which might be hard to measure, e.g. effect locally on disadvantaged groups, possible local benefit in creating jobs. The notion of “best value” is indeed generally a thorny issue. The BIS document published in November 2011, entitled “Delivering best value through innovation: forward commitment procurement”, does however provide useful guidance. As an explanation of where it has come from, this guidance explains, “[this] comprises the European Union (EU) procurement directives, the EU Treaty principles of non-discrimination, equal-treatment and transparency, and the Governments procurement policy based on value for money”. However, the “best value” solution may not necessarily be the cheapest, and this is particularly relevant to innovative solutions (explained elsewhere in the document):

“Value for money should not be seen as a barrier to innovative solutions. Sometimes innovative offers can look more expensive in the short term, but will be a better offer in the long term. Although not listed explicitly in the Regulations, criteria involving innovative solutions may be used to determine the most economically advantageous tender, where they provide an economic advantage for the contracting authority which is linked to the product or service which is the subject matter of the contract.”

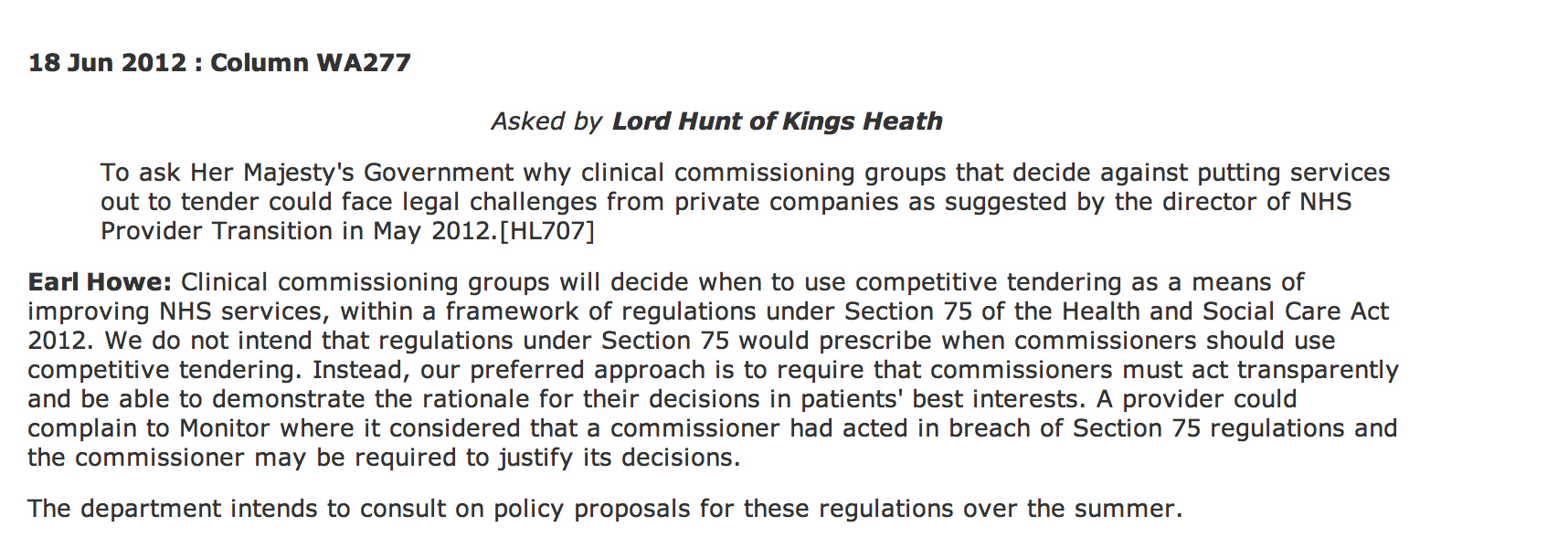

According to Hansard, Earl Howe did not intend to prescribe when ‘competitive tendering’ should exist under section 75 Health and Social Care Act (2012):

However, the problem is that Monitor can step in if the CCGs get the decision “wrong”.

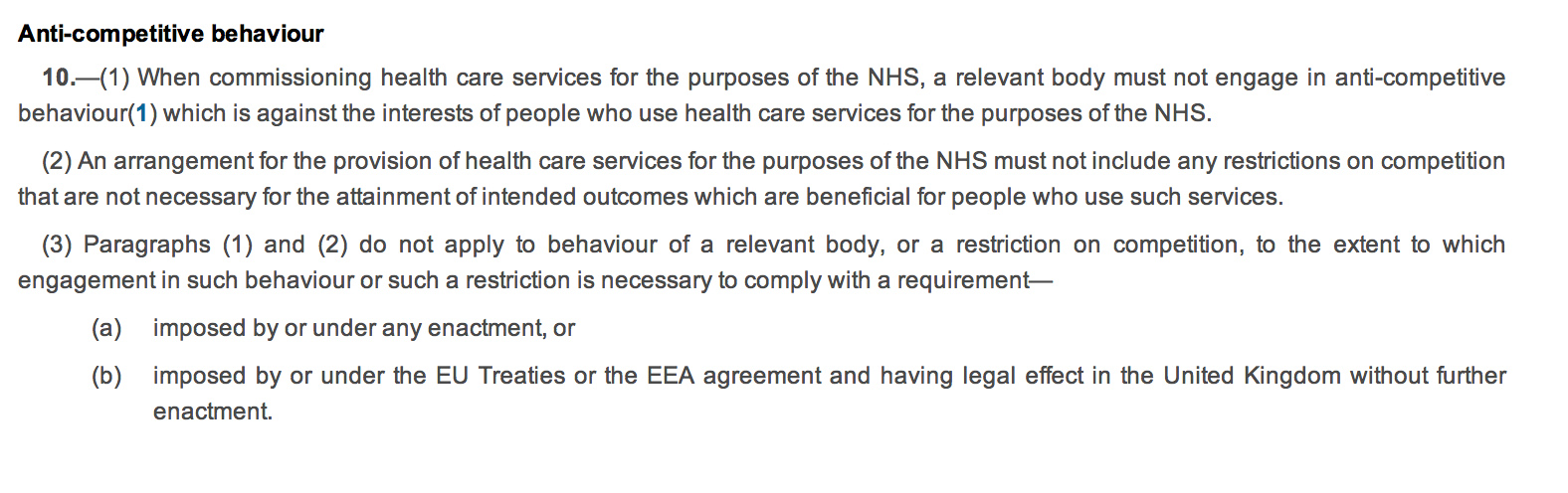

Regulation 10 governs the “anti-competitive principles”. The drafting of this is ‘clunky’, with 10(2) possibly the worst example of a double negative in drafting which offends the basic legal drafting principle of clarity. The Coalition has decided to enmesh the Act full-frontally in domestic and EU competition law (as shown in regulation 10(3)), whereas before there was a lifeline for escape from competition law because of the ambiguity in whether the terms “undertaking” or “economic activity” would apply to the NHS (a downloadable document is here). This is remarkable politically in that often governments describe the EU as imposing unnecessary legislation on UK citizens; here it is almost as if the Coalition is using EU arguments about general procurement law, applicable to widgets not clinical decision-making, to justify their NHS legislation. Again, a nuance in the drafting is clearly that a NHS provider cannot be given any preference in procurement. This reflects a notion in general procurement policy, of “equal treatment of providers”, designed to encourage confidence in the process and preventing abuse of the process for undue preference to any particular suppliers. Whilst this is an objective of the “UNICTRAL model law on the procurement of goods, construction and services” in the preamble, it is thought to be a subsidiary function, and is intended to protect against overt corruption and bribery.

It is an altogether different phenomenon if Parliament had intended to offer a “comprehensive”, nationally-planned health service, and therefore wished to have a corpus of NHS providers to fulfil this aim. There are no legal limitations on Parliament. It can pass any law whatsoever. The classic example (Sir Leslie Stephens, 1882) is that Parliament could pass a law ordering the death of all blue eyed babies.

It is an altogether different phenomenon if Parliament had intended to offer a “comprehensive”, nationally-planned health service, and therefore wished to have a corpus of NHS providers to fulfil this aim. There are no legal limitations on Parliament. It can pass any law whatsoever. The classic example (Sir Leslie Stephens, 1882) is that Parliament could pass a law ordering the death of all blue eyed babies.

It is left up to Monitor to “regulate” breaches of this statutory instrument (regulations 13-17). What is striking is that the legislation appears to suggest that all “complaints” are funneled through Monitor, rather than a general health ombudsman or judicial review (presumably CCGs are still public bodies serving a public function in the public interest). The system is therefore highly dependent on Monitor running a fully explicable process, and the statutory guidance on this will be critical. We have already seen this week the judiciary ‘clearing up’ bad law from parliament. The chances are that CCGs, without adequate legal advice, will end up being powerless in querying any decisions that Monitor has judged “incorrect”, which they are fully entitled to do of their own accord according to Regulation 13(2).

The legislation, whatever the intentions of the Conservatives, Liberal Democrats, or Labour, makes it much harder for the NHS to justify procurement from NHS providers without challenges, and whose side Monitor takes on these challenges is incredibly hard to predict because of the complexities in determining what is “best value”.

Does the UK really have an ability to opt out of law imposed by the EU? Guest blog by Matthew Scannell (@studentlawyer_)

At the present time, the European Communities Act [1972] provides that the UK is bound by law enacted by the European Union (“EU”), whereby provisions of EU law are superior to domestic law, in that EU provisions take precedent in circumstances where there is conflict between the two sources of law.

However, David Cameron’s recent proposal for a referendum to determine the UK’s future within the EU has fuelled questions as to whether the UK may finally ‘break free of the shackles’ that appear to have been imposed on it by the EU. Such a referendum could refine constructively the relationship between the UK and EU, and possibly reduce the effect that EU law has within the UK.

The first question to consider is whether the UK has the power to opt out of provisions of law imposed on it by the EU. In line with the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty, the UK Parliament has the ability to repeal the European Communities Act (the statutory instrument which brought the UK into the EU) and thus revoke its membership with the EU. This would mean that the provisions of law enacted by the EU would become void within the UK. However, it would be wrong to conclude that the UK may simply ‘pick and choose’ which provisions of EU law it wants to apply. If the UK attempted to take such a course of action, the EU may have the right to impose sanctions against the UK. I would suggest that the only way the UK may take free of provisions of EU law would be to legislate expressly for the revocation of its membership within the EU.

The UK’s ability to revoke its membership with the EU would then be dependent on whether a referendum such as the one proposed by David Cameron takes place, as well as the public voting against staying in Europe on such renewed terms. The second question to consider is whether the UK should merely make attempts to opt out of the law imposed on it by the EU, and what the consequences of such a course of action would be. The EU has limited law-making power within the UK, and so can only legislate in the areas that the treaties provide for. Therefore the consequences of such an attempt to remove the EU’s law-making power within the UK would be of limited effect.

I would then suggest that the extent to which the law would change if the EU was no longer recognised by the UK as a superior source of law would be dependent on the current status given to that law by the EU. Essentially there are two broad types of EU law; regulations and directives. Article 189 of the Treaty of Rome provides that regulations are binding on all member states and all members have to accept the same definition. This is in contrast to directives, where member states have scope to adjust or tinker with the definitions of such directives so that it may fit in with the requirements of national law. I would therefore suggest that it is less likely that directives, such as the Working Time Directive, would be subject to wholesale amendment or repeal, as such provisions of EU law have been read in such a way which ‘fits’ within national law.

However, if the UK was seen to split from the EU then there would be less regulation over the laws that are enacted by Parliament, as the UK would be moving towards a theory of parliamentary sovereignty outlined famously by AV Dicey. The only real protection that could then be used to safeguard against Parliament abusing its power is the political safeguard of democratic elections, although the judiciary also provides protection through the “separation of powers”, which offers useful “checks and balances”. This worry is compounded by the fact that laws enacted by the EU, such as the Working Time Directive, are necessary and proportionate, safeguarding against potential abuses by certain interest groups. If the UK Parliament was afforded the power to legislate for areas in relation to the work place, this could quite potentially result in the exploitation of certain citizens within society.

In my opinion, then, the only feasible way that the UK opt out of specific provisions of EU law would be to expressly state that they are making a move away from the EU by repealing the European Communities Act. Proposals for a referendum may have politically “lined the stomach of the UK”, but this is only the first step on the road to a different relationship between the UK and the EU – and there are certainly several crossroads to be negotiated along the way.