Home » Posts tagged 'law'

Tag Archives: law

How do we interpret the significance of living well with dementia?

Strange through it may seem, I have been most influenced in my philosophy of living better with dementia by the late Prof Ronald Dworkin who died in 2013 at the age of 81 (obituary here).

One recent campaign has the tagline ‘Right to know’ from the UK Alzheimer’s Society – about the right for you to know if you have dementia as a diagnosis, a right to treatment, and right to plan for the future.

I feel that people newly diagnosed with dementia have other rights too. I would say that, wouldn’t I. Above all, I feel that people who have received a diagnosis of dementia have a right to live well. This is truly a legal right, as this is not negotiable under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Recent case law, in the judgment from Lady Hale in R v Cheshire West and Chester Council (et al), re-emphasises that human rights are inalienable. And given that dementia is a disability under law, the right of that person with dementia is a right to dignity, reinforced by our universal human rights.

Focusing on a right to treatment further consolidates the biomedical model which I think is utterly unjustified. We have just seen the peak of one of the most successful campaigns ever mounted by Pharma and large charities for dementia to raise funds for pharmaceutical approaches to dementia. But at the expense of offering jam tomorrow there was very little on offer for people currently living well with dementia. The answer given to Helga Rohra by the World Dementia Envoy gave little in the way of concrete help for people currently trying to live well with dementia. And the ignorance of this is not benign – for the millions of dollars or pounds sterling spent on molecular biology and orphan drugs for dementia to meet the deadline of 2020, this amount of money is being taken out of the pot for developing the evidence base for and for strategies for living better with dementia in a non-pharmacological way.

Just a minute. Look at the evidence. The medications known as cholinesterase inhibitors are generally thought not to slow down the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in humans, even if they have a short valuable time window of use for symptomatic treatment In the UK, and across the world, there has been a drive for reducing the number of inappropriate prescriptions of antipsychotics for people living with dementia; there is now a growing consensus that where symptoms exist they often are due to a fundamental failure in communication with that person living with dementia, and often other therapeutic routes are much more suitable (such as psychological therapies).

The great FR Leavis, intensely under promoted at Cambridge, reminded us that criticism had to be free and flexible: and hence the famous description of the ideal critical debate as an ongoing process with no final answer: “This is so, isn’t it?” “Yes, but …”

Criticism of the English dementia policy may seem like criticism of senior clinicians, senior personnel in charities or senior politicians, but Leavis gives us a powerful reminder to stand up for what it is right. Surely, people living well with dementia have a right to comprehensive high quality dementia care and support? The evidence in support of multidisciplinary teams, including social work practitioners, speech therapists, doctors, cognitive neuropsychologists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, working to produce pro-active plans is now overwhelming. There is now increasing evidence that specialist nursing could prevent many acute admissions to secondary care.

As the late Ronald Dworkin asked us to consider, we might think about what makes an “interpretation” true. As Dworkin notes, psychoanalysts interpret dreams, and lawyers interpret contracts. I would go as far as to say clinicians, of various backgrounds, interpret whether a person presenting with a particular cluster of mainly psychological symptoms is presenting with a dementia. I don’t think the diagnosis of dementia is necessarily easy to make. Given that you’re giving a diagnosis of dementia not just to a person with possible dementia but also to his friends and family it is essential to get right; not to misdiagnose depression as dementia for example. My gut instinct is that doctors of all variety do their utmost to get this diagnosis correct. I think there is also a degree of interpretation in how much a person will successfully adapt to their diagnosis in taking an attitude of ‘living well’, or how they will put their faith in pharmacological treatments. The drugs do work for some people for part of the time after diagnosis, so their importance must not be diminished either. I think there is also a degree of interpretation of how disruptive a diagnosis of dementia might be for that person and his or her community.

Dworkin also notes you would be prone to sack a Judge who said, “I am not sure if this person is guilty or not guilty. I think he’s guilty, but you could probably find great many judges who finds the person not guilty.” It is possible that in the more complicated cases a Doctor might find a person living with dementia, another one not living with dementia. Dementia is presented as a definite diagnosis, a binary decision; but this would be to ignore that even the diagnostic criteria, such as the critical importance of memory (or not), has changed with time. Likewise, there has been a growing conflation of whether you fail a series of tests is the same thing as having a diagnostic label; see for example how some people recorded as having ‘delirium’ in the medical notes have in fact, strictly speaking, failed a specific set of screening tools.

But we can say that there are non-medical routes which are not an idle exercise but are of a person flowing from the diagnosis of probable dementia. This is there is much which can do to enhance the living environment of a person, whether a hospital ward, home or town. Or somebody can be directed towards advocates who can help persons with dementia communicate decisions. Or a person can be directed to inexpensive assistive technologies or lifestyle adjustments that can allow a person to live with dementia just like any other disability. This is framing long term care as living with a condition, rather than the single hit treatment.

Dignity, independence and a vast array of other values will, I feel, are a very necessary outcome of this more helpful approach to dementia. The person who has received a diagnosis of dementia is as much of a need of an acknowledgement of uncertainty as a water-tight explanation. The person who has received a diagnosis of dementia needs to be partnership with the people who wish to share that diagnosis with him or her.

I feel it is now time to unmask the medical professional who may simply be not be able to cope with this cultural shift. The medical profession does not know all the answers, nor indeed do all the people who’ve signed up to the Pharma script.

People who want to live better with dementia can be secure in the knowledge that that is their human right. They have a right to this solution, wherever it comes from.

Reference

Is there truth in interpretation? Prof Ronald Dworkin

The GMC needs to be a good citizen too

The topic of how corporates act as ‘good citizens’ has been significant in recent years, for example the synthesis of work on strategy and society.

Broadly speaking, this work has identified a number of different concepts which are vital to corporate social responsibility.

The first is a ‘moral obligation’.

This must include honesty and integrity, and directly relates to domain 4 of the code of conduct “Good medical practice” for standards in trust and probity from the “General Medical Council” (GMC). Moral behaviour and legal regulation are dissociable. A legal ‘duty of candour’ or ‘wilful neglect’ are enforcement mechanisms for people telling the truth and protecting against deliberate malicious behaviour. But these are undeniable moral imperatives too. If the clinical regulator finds itself in dealing with a case in an unnecessarily protracted length of time which is disproportionate to reasonable standards, the clinical regulator should make an appropriate apology, ideally.

Sustainability is important if the clinical regulator is to be ‘in the long game’ rather than grabbing headlines for being seen to be tough on misfeasance from individuals. This means in reality that the clinical regulator should be sensitive to the environment and ecosystem in which it operates. If it is felt, for example, that politically and economically it is expedient to pursue ‘efficiency savings’, the regulator must have a sustainable plan to ensure that it is able to ensure that such savings do not impact on patient safety. The raison d’être of the GMC is supposed to be promote patient safety. A proportion of the Doctors will be unwell. The legal precedent is that conduct which is so bad cannot be condoned whatever the reason. However, it is also true that ‘but for’ alcoholism, for example, certain problems in misconduct and poor performance would not have occurred. An ill doctor is about as much use economically as somebody out of the service entirely, so it is an economic sustainable argument that the health of doctors should be an imperative for the NHS. A ‘patient group’ within the GMC would go a long way to demonstrate that the GMC is capable of playing its part within a wider ecosystem. I know of no other important entity which does not have one.

Thirdly, there should be a license-to-operate. This cannot be overstated. ‘Mid Staffs’ commanded much momentum in the media which was a problem for both the medical profession and its integrity, and yet there is still an enduring issue whether the GMC were able to regulate this as best they could under the confines of the English law and codes of practice. The GMC are also yet to report on the deaths of Doctors awaiting Fitness to Practise hearings, and the outcome of this will be essential for Doctors to ‘buy in’ literally into wishing to pay their subs.

Last of all is reputation. This goes beyond the popularity on a Twitter stream. At the moment, there is concern that neither the medical profession nor the public feel very satisfied about the performance of the GMC. There is uncertainty what the public perception of the GMC is; many feel that it is a general complaints agency, when it is, in part, to regulate the performance of individual Doctors. There’s no statutory definition of what ‘unacceptable misconduct is’, and hugely relevant to the reputation of the medical profession. This had been addressed in the English Law Commission’s proposals for regulation of clinical professionals, which are yet to see the light of day. Without this definition, the GMC can simply come down heavily on behaviour which it feels is embarrassing with impunity, whatever the potential other contribution of that doctor might be. It is quite unpredictable what the consistent set of standards where members of the public feel wronged might be for this; the GMC is very unwilling to be seen as a ‘light touch’ against members of the public who want tough sanctions.

There are so many aspects how the GMC could demonstrate its willingness to be a good citizen, which could help with the four points above. I feel as a person who has been through the whole cycle of having been regulated, who takes his credentials of being a NHS patient and being a student lawyer regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority rather seriously, there are constructive ways to move forward.

Firstly, I would like to see a ‘user group’ of Doctors who’ve been through the regulatory process, and who have had bad health, who might wish to volunteer on helping the GMC with improving its operational output. Secondly, I understand the temptation to throw ‘red meat’ at the readership of certain newspapers. But likewise, the GMC could make more effective use of local dispute resolution mechanisms, looking at what the Doctor, the Trust and the member(s) of the public would like as a compromise to problems. This could have the aim of having a Doctor where reasonable corrective action has taken place finding himself or herself being able to return to work. The current situation has evolved through history as being adversarial, and this can err towards catastrophising of problems rather than wishing to solve them. Likewise, there is a public perception that some issues are completely ‘shut down’ before any attempt to investigate it. Thirdly, the GMC must be aware, I feel, of the evolving culture and landscape of the medical profession across a number of jurisdictions. This means the GMC, patients and professionals could be, if they wanted to, united in their need to uphold the very highest standards of patient safety. Clinicians work in teams, and techniques such as the ‘root cause analysis’ have as an aim finding out where the performance of a team has produced an inadequate outcome. Furthermore, there is no point in one end of the system urging learning from mistakes and organisational learning with the other end of the system cracking down heavily on individuals, with the effect that some individuals never work again.

Like whole person care in policy, the clinical regulator should be concerned about all the needs of an individual, including health needs, public safety promotion, and the needs of the service as a whole. I have every confidence that the GMC can rise to the challenge. It’s not a question of light touch regulation, but the right touch regulation.

And, as per medicine, sometimes prevention is better than cure.

Isn’t it time to admit failure in ‘regulating cultures’?

It is alleged that a problem with socialists is that, at the end of the day, they all eventually run out of somebody else’s money. Perhaps more validly, it might be proposed that the problem with all politicians is that they all run of other people to blame?

It is almost as if politicians form in their minds a checklist of people they wish to nark off systematically when they get into government: candidates might include lawyers, Doctors, bankers, nurses, disabled citizens, to name but a few.

Politicians are able to use the law as a weapon. That’s because they write it. The law progressively has been reluctant to decide on moral or ethical issues, but altercations have occurred over potentially inflammable issues such as ‘the bedroom tax’. Normative ethics takes on a more practical task, which is to arrive at moral standards that regulate right and wrong conduct.

There has always been a tension between the law and ethics. As an example, to prove an offence in the English criminal law, you have to prove beyond reasonable doubt an intention rather than a motive, for example that a person intended to burn someone’s house down, rather than why he had intended so. Normative ethics involve articulating the good habits that we should acquire, the duties that we should follow, or the consequences of our behaviour on others. The ultimate ‘normative principle’ is that we should do to others what we would want others to do to us.

Parliament is about to get its knickers in a twist once again over the thorny issue of press regulation. However, there is a sense of history repeating itself. A few centuries ago, “Areopagitica” was published on 23 November 1644, at the height of the English Civil War. It is titled after Areopagitikos (Greek: ?????????????), a speech written by the Athenian orator Isocrates in the 5th century BC. (The Areopagus is a hill in Athens, the site of real and legendary tribunals, and was the name of a council whose power Isocrates hoped to restore).

“Areopagitica” was distributed via pamphlet, defying the same publication censorship it argued vehemently against. As a Protestant, Milton had supported the Presbyterians in Parliament, but in this work he argued forcefully against the Licensing Order of 1643, in which Parliament required authors to have a license approved by the government before their work could be published.

Milton then argued that Parliament’s licensing order will fail in its purpose to suppress scandalous, seditious, and libellous books: “This order of licensing conduces nothing to the end for which it was framed.” Milton objects, arguing that the licensing order is too sweeping, because even the Bible itself had been historically limited to readers for containing offensive descriptions of blasphemy and wicked men.

England has for a long time experienced problems with moving goalposts in the law, and indeed the judicial solutions sought have varied with the questions being asked. Lord Justice Leveson acknowledged that the “world wide web” was a medium subject to no central authority and that British websites were competing against foreign news organisations, particularly in America, which were part of no regulatory system.

Leveson once nevertheless proposed that newspapers should still face more regulation than the internet because parents can ‘to some extent’ control what their children see online, while they could not control what they see on a newsagent or supermarket shelf.

‘It is clear that the enforcement of law and regulation online is problematic,’ said Lord Justice Leveson at the end of his year-long inquiry into press ethics.

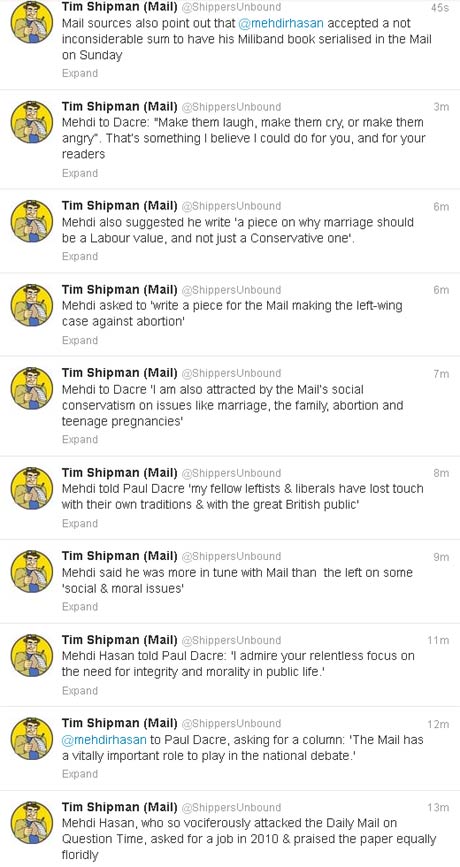

An attempt at ‘regulating culture’ was dismissed in the Leveson Report largely through arguing that the offences were substantially already ‘covered’, such as trespass of the person or phone hacking. And yet it is the case that there are ‘victims of phone hacking’ who feel that we are unlikely to be much further forward than we were before spending millions on an investigation into journalistic practices. In recent discussions this week, eyebrows have been raised at the suggestion that Ed Miliband could write to senior members in the Mail-on-Sunday empire to suggest that the culture in their newspapers is awry, and to ask them to do something about it. It could be argued it is none of Miliband’s business, except that Miliband would probably prefer the Mail to write favourably about him. Such flexibility in judgments might be on a par with Mehdi Hasan changing his writing style and target audience within a few years, as the recent Twitterstorm demonstrates.

The medical and nursing professions have latterly urged for an approach which is not overzealously punitive. There have been very few sanctions for regulatory offences in Mid Staffs or Morecambe Bay, for example.

Robert Francis QC still identified that an institutional culture which put the “business of the system ahead of patients” is to blame for the failings surrounding Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust. Announcing the publication of his three volume report into the Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust public inquiry, Mr Francis described what happened as a “total system failure”.

Francis argued the NHS culture during the 2005-2009 period considered by the inquiry as one that “too often didn’t consider properly the impact on patients of decisions”. However, he said the problems could not “be cured by finding scapegoats or [through] reorganisation” of the NHS but by a “real change in culture”. However, having identified the problem, solutions for cultural ‘failure’ in the NHS have not particularly been forthcoming.

There are promising reports of ‘cultural change’ in the NHS, for example at Mid Staffs and Salford, but some aggrieved relatives of patients still have a feeling that ‘justice has not been done’. There has been no magic bullet from the legislature over concerns about bad practice in the NHS, and it is unlikely that any are immediately forthcoming. There is little doubt, however, that parliament improving the law on safe staffing or how whistleblowers can raise issues in the public interest safely might be constructive steps forward. There therefore exists how the law might conceivably ‘improve’ the culture, and one suspects that this change in culture will have to permeate throughout the entire organisation to be effective. That is, fundamentally, people are not punished for speaking out safely, and, whilst legitimate employers’ interests will have to be protected, the protection for employees will have to be necessary and proportionate equally under such a framework.

Journalism and the NHS are not isolated examples, however, Newly released reports into the failures of management at several major banks – HBOS, Barclays, and JP Morgan among them – show that some of the worst losses had roots deeper than the 2008 credit crisis. It is said that a toxic internal culture and poor management, not the subprime mortgage collapse, caused billion-dollar losses at some of the world’s largest banks

In an argument akin to that used to argue that there is no need to regulate the journalism industry, the banking industry have long maintained that a strong feeling of internal competition can be healthy for profitability, but problems such as abject fraud and misselling of financial products are already illegal.

The situation is therefore a nonsense one. There is a failed culture, ranging across several diverse disciplines, of politicians wishing to use regulation to correct failed cultures. Cultures of an organisation, even with the best will in the world, can only be changed from within, even if the public, vicariously through politicians, wish to impose moral and ethical standards from outside.

Whichever way you wish to frame the argument, it might appear ‘we cannot go on like this.’ It is a pathology which straddles across all the major political parties, and yet all the parties wish to claim that they have identified a poor culture.

Their lack of perception about what to do with these problems is perhaps further evidence that the political class is not fit for the job.

Compromise agreements, redundancy and efficiency – the ingredients of a ‘perfect storm’ in the NHS?

The NHS spent £15 million in three years on gagging whistleblowers, according to the Daily Mail. In just three years there were 598 ‘special severance payments’, almost all of which carried draconian confidentiality clauses aimed at silencing whistleblowers. They cost the taxpayer £14.7million, the equivalent of almost 750 nurses’ salaries.

Whistleblowers have found them at the end of such agreements, and why the NHS culture is not one of transparency and trust is a damning observation. Compromise agreements have also been used in ‘genuine’ situations of redundancy. Redundancy arises when an employer either:

- Closes the place of work; or

- Reduces the number of employees which are employed by it.

The employer is under an obligation to pay a redundancy award to any employee who is dismissed by reason of redundancy if that employee has two years’ service or more. From an employee’s perspective, it is quite common that when employment ends, you and your employer agree to enter into a “Compromise Agreement”. The purpose of the compromise agreement is to regulate matters arising from the termination. A compromise agreement is a legal document that records the agreement between an employee and employer whereby the employee agrees to ‘compromise’, or not to bring, a claim against the employer in relation to any contractual or statutory claims they may have in relation to their employment or the manner of its termination. This type of agreement is typically in return for the payment of a sum of money from the employer to the employee. It may also contain details of additional ancillary agreements between the parties on topics such as: ongoing confidentiality/ restrictions, agreed form references etc.

Compromise Agreements can be very effective and, in essence, amount to a ‘clean break’ that, hopefully, benefit both parties and enable everyone to move on. They are enshrined in law through s.203 Employment Rights Act (1996). A dismissal by reason of redundancy can amount to an unfair dismissal. There are other statutory reasons for unfair dismissal which are allowed, which are cited earlier in the Employment Rights Act.

A dismissal by reason of redundancy can amount to an unfair dismissal. Issues which render such dismissal unfair often include:-

- The selection of a pool of employees from which the redundant candidate is chosen;

- The criteria for such selection; and

- Failure to consult appropriately.

The House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts published a document “Department of Health: progress in making NHS efficiency savings: Thirty-ninth Report of Session 2012–13″ on 13 March 2013. The discussion between Meg Hillier and Mike Farrar talks about redundancy payments, but interestingly this document does not refer to ‘compromise agreements’ once.

“Q29 Meg Hillier: Maybe at chief executive level, but I know for a fact that there are people out there who have taken generous redundancy payments—they may genuinely have thought they were not going to work in the NHS again—but there is such demand for their skills and services that they have been brought back in. There seems to be no real ability to have safeguards. I know they are your members, so maybe it is in your interests for them to get these positions, but this is about all taxpayers’ money, and in the end it affects everyone.

Mike Farrar: We have tried to support the management of people through the system to the best possible place to get the best value for taxpayers; that is what we would want to see. The reforms have abolished authorities and organisations. People have not been able to take redundancy unless they were eligible for redundancy on the basis that their organisation has been abolished. That has allowed management cost savings of a significant level—

Q30 Chair: Well, we do not know, because you might have had a whole load of management costs in terms of redundancy, with people then re-emerging elsewhere. We are very sceptical.

Mike Farrar: I think the reforms of this House are responsible for certain people having been eligible for redundancy. There is a notion that those individuals leapt at the chance to be made redundant in order to deploy their services back, but that has only been created in terms of an opportunity because of reforms passed by the House. Some of these points were made during the passage of the Bill. “

HM Government has never published its “Risk Register” for the Health and Social Care Act (2012), despite the guidance involving the Information Commissioner. Today’s Report published by the National Audit Office on the use of compromise agreements makes for depressing reading:

“There is a lack of transparency, consistency and accountability in the use of compromise agreements in the public sector and little is being done to change this situation, an investigation by the National Audit Office has found.

Public sector workers are sometimes offered a financial payment in return for terminating their employment contract and agreeing to keep the facts surrounding the payment confidential. The contract is often terminated through the use of a compromise agreement and the associated payment is referred to as a special severance payment.

The spending watchdog highlights the lack of central or coordinated controls over the use of compromise agreements. The NAO was not able to gauge accurately the prevalence of such agreements or the associated severance payments. This was down to decentralized decision-making, limited recording and the inclusion of confidentiality clauses which mean that they are not openly discussed. No individual body has shown leadership to address these issues; the Treasury believes that there is no need for central collection of this data.”

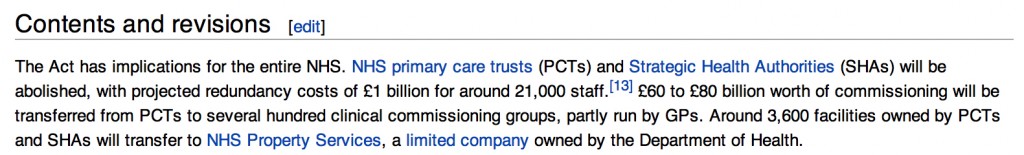

It could be there that there is a fundamental faultline in how performance management in the NHS is currently being implemented, in which commercial lawyers are not quite silent bystanders. That is, the NHS has found itself in a situation where it is generating efficiency savings, which do not get ploughed back into frontline care. A reasonable place to start is also the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012), and this complex strategic restructuring has obviously had its opportunity cost, even as described on Wikipedia here:

When you have CEOs and NHS Foundation Trusts being judged by their ‘efficiency savings’ which may involve redundancies (though these parties will argue that many of these staff are mostly employed back), the performance management system is heavily weighted against long-serving staff with experience and skills of working in the NHS who ought to be cherished for ‘adding value’. This is clearly a massive fault with how the NHS rewards ‘success’ in the NHS (and if the CQC’s recent scandal and more are anything to go by does not appear to punish ‘failure’ in the regulatory system, either.) And when you add to that that the experience of NHS whistleblowers, often at the receiving end of compromise agreements with suboptimal legal advice (whereas the NHS has access to the best commercial and corporate lawyers), is that whistleblowers tend to get humiliated and marginalised to such an extent that they never work again, you can see how compromise agreements, while certainly enshrined in law for a legitimate person, along with an alleged lack of teeth of the Public Interest Disclosure Act (1998), has successfully allowed a ‘toxic culture’ to perpetuate very successfully indeed?

Why George Osborne's parking spot is such a problem

George Osborne wished to approach this week, Master Tactician that he is, setting the news agenda away from ‘The Millionaire’s Tax Cut’, for a debate about welfare reform. However, George Osborne is stuck in a mental rut, as well as perhaps “gutter politics” as proposed by Ed Balls MP, that the welfare reform debate is about shirkers v strivers, not about the pensions of the elderly which in fact constitute the bulk of the budget currently. Osborne in Torytown Toryshire earlier this week used the same image of shirkers being in bed with their curtains closed (with some of the words interchanged) while strivers go to work in the morning. Osborne therefore fundamentally wants to articulate his welfare debate in the language of ‘fairness’. He doesn’t wish to talk about those Directors of HBOS which have been alleged to underperform and who had been holding ludrative positions elsewhere. Not that kind of fairness. He doesn’t particularly wish to talk about tax avoidance – even though he has a “crack squad” of a handful of people looking into the billions which disappear because of multinational tax avoidance. No, instead, Osborne is pathologically stuck in a mental mindset of pointing the finger “at those below you” who earn more by doing less, not “at those above you” who earn more by doing much less.

Enter Mick Philpott. Like Ed Miliband ‘wants to have a conversation with you’, George Osborne wants you to have a debate about shirker psychology. However, Osborne’s fundamental problem is that benefit fraud, even according to the DWPs’ own statistics, is a relatively minor problem compared to other problems in the welfare budget. Also, it is dangerous to construct policy on the basis of one extreme example, for the same reason you would not necessarily reconstruct the entire policy of inheritance tax based on the recent Seddon case. The Daily Mail and George Osborne have undoubtedly succeeded in their primary goal of having people “discuss” this issue; except the discussion is one of competing shrills, of blame and counterblame, and there is a lot of noise compared to a weak signal.

This morning, George Osborne is facing more criticism over welfare reforms after he was photographed getting into a car parked in a disabled space. The picture shows the Chancellor being picked up by his official car in a restricted bay, after he stopped for lunch at the Magor services on the M4 in Monmouthshire. Senior Conservative sources said he had been to buy food from McDonald’s and was not aware the Land Rover had been inappropriately parked. George Osborne’s parking spot, on the front cover of the Daily Mirror, is a problem for a number of reasons. The embarrassing incident comes as the chancellor stands accused of pushing through welfare reforms that will hurt the disabled, including housing benefit cuts for people with spare rooms. The disability charity Scope says 3.7 million people will be affected by the government’s welfare cuts, losing £28.3bn of support by 2018. The charity’s chief executive, Richard Hawkes, told the Mirror the incident “shows how wildly out of touch the chancellor is with disabled people in the UK”. He said: “They will see this as rubbing salt in their wounds.

The issue is that George Osborne’s “team” appears to be taking up a parking space which should be taken up by a “real” disabled citizen. This taps into the “hypocrisy” attack of voters which is a very potent one – and when it is combined with an attack on someone perceived as privileged, there is a lot of political capital in it. This argument is only tenable if it happens that George Osborne’s driver is not disabled; it is perfectly possible for him or her to be a person with an obvious disability or a “hidden” disability. If the criticism of Osborne’s “team” is correct, then the idea of someone claiming something fraudulent is exactly what Osborne has seemed to accuse disabled citizens of. Osborne’s defence is one of ignorance, and indeed it is perfectly possible that his “team” parked in this parking spot negligently or innocently rather than fraudulently. However, it is a fundamental tenet of the English law that ignorance is no defence, in other words “ignorantia non excusat juris”. Nobody is above the law, including George Osborne, even if it is possible for the Coalition to rewrite hurriedly the law if it does not suit their purposes with the help of Labour (such as happened recently with the Workfare vote over which a number of Labour MPs were forced to rebel.)

The starting point is, of course, that George Osborne is inherently unpopular with Labour voters (and some within the Conservative Party say that he is inherently unpopular with many within the Conservative Party as well.) A lot of this is “personality politics”, in part contributed to by Osborne himself who appears to revel in playing a ‘pantomime villain’. He was openly very hostile to Alistair Darling, but since May 2010 when the economy was in fact in a fragile recovery, he has driven the economy at high speed in the reverse gear, and, whether or not the service sector recovers, he has taken the UK economy through a “double dip”.

Of course, the issue is a “storm in a teacup”, compared to NHS management, the management of the economy, etc., and Conservatives will feel that it is ludicrous that Osborne is being harrassed into apologising for a relatively minor incident. It is impossible to locate somebody who has never made a mistake. However, in the political “rough-and-tumble” ‘every little bit helps’, and the incident is not an isolated one contributing to an overall ambience of perceived incompetence. The other famous incident is of course when Osborne claimed that “his team” was unable to upgrade his standard class ticket to First Class, while he was merrily sitting in First Class. After a while these incidents, while perhaps unfortunate, all blend into the “pantomime villain” persona of George Osborne as a man who simply doesn’t care. A man who doesn’t care is normally pretty unattractive to voters, even in “white van” (or “white suit”) Tatton.

The legal issues in the statutory instrument (2013, No. 257) on NHS procurement in England

The key document in question is here.

In a nutshell, it has thrust private sector ‘competitive tendering’ in the procurement of NHS services into the limelight.

The legislature, as recommended by the executive, has an obligation to provide law that is clear and predictable, and the judiciary can only rely on the Acts on the statute books and any supporting discussions of what parliament might have intended. It is at the heart of parliamentary sovereignty that parliament can do what it wishes. There is, unfortunately, a large number of issues concerning this statutory instrument 2013 No. 257 concerning procurement in England. These embrace a plethora of commercial and legal, not just political, considerations, which do need to be discussed as a matter of some urgency in the public interest. Such discussion will be to the benefit of all involved parties.

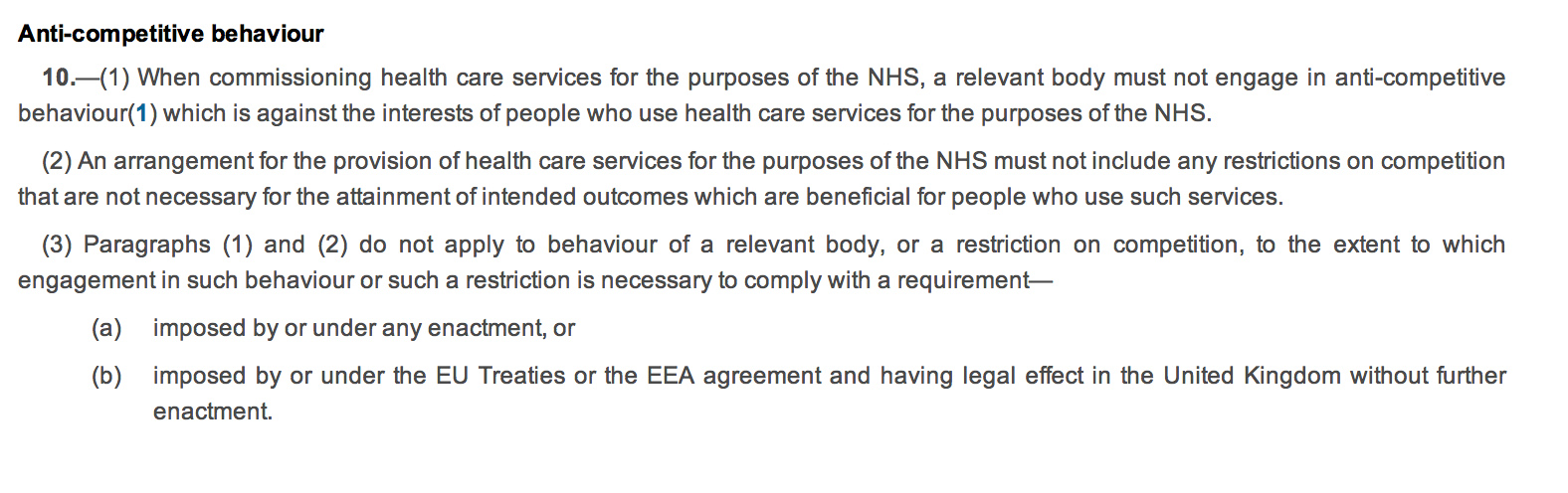

The judiciary must have a clear understanding of how this law was arrived at, for it to interpret the ‘intention of parliament’ when any disputes arise as they indeed will. To help it, it has the Bill and Act itself, as well records in Hansard. The case and statute law, both domestic and EU law, have a recent history in effecting English NHS health policy, but only in as much the NHS has encroached upon ‘undertakings’ and ‘economic activity’ in EU law. The Health and Social Care Act (2012) has changed the legal climate substantially; indeed, the ambit of competition is thrown very wide indeed, as reflected in Regulation 10.

Section 75 of the Health and Social Care Act has firmly enmeshed the Act in competition legislation, parallel to but distinct from previous legislation such as the Public Contracts Regulations (2006). However, the adoption of key concepts and themes from the European law, voluntarily by the English legislature as proposed in the statutory instrument, makes it rather unclear as to the actual ‘direction of travel’. It is as if Parliament has wished to enmesh the NHS in European competition and procurement law, without any democratic scrutiny. The aforementioned statutory instrument is particularly vague on the precise functions of Monitor in the distinct phases of award and execution of procurement, does not map out how Monitor is to function on behalf of key stakeholders in the NHS along with other regulatory processes (such as judicial review or the health ombudsman), and how precisely this English legal framework will operate alongside other approaches (such as the UNCITRAL Model law, European regimens, and World Trade Organisation).

Critically, it seems quite mysterious how overall this particular method was chosen (formal tendering, as opposed to less structured methods of competitive tendering such as requests for proposals and quotations, or single-source procurement), when the discussions in the lower and upper Houses of Parliament did not heavily lean in this direction in the first place. (Such methods are extensively discussed in ‘Regulating Public Procurement: National and International Perspectives’ (2000) Sue Arrowsmith, John Linarelli and Don Wallace Jr. Kluwer Law International). This obligatory competitive tendering mechanism for the majority of tenders is a robust method of making sure as many contracts are awarded to the private sector as possible. There would be nothing to prevent parliament from legislating for a minimum of NHS services to stay in the NHS, as that would not offend any law in Europe; it does not distort the market, but for public policy reasons could easily be argued to have a legitimate reason. For example, if a key provider, e.g. of blood products, went bust, this could be the detriment of the entire service, and protection for such a service can easily be justified under statute.

Some specific points which are particularly noteworthy are raised in the Appendix.

APPENDIX

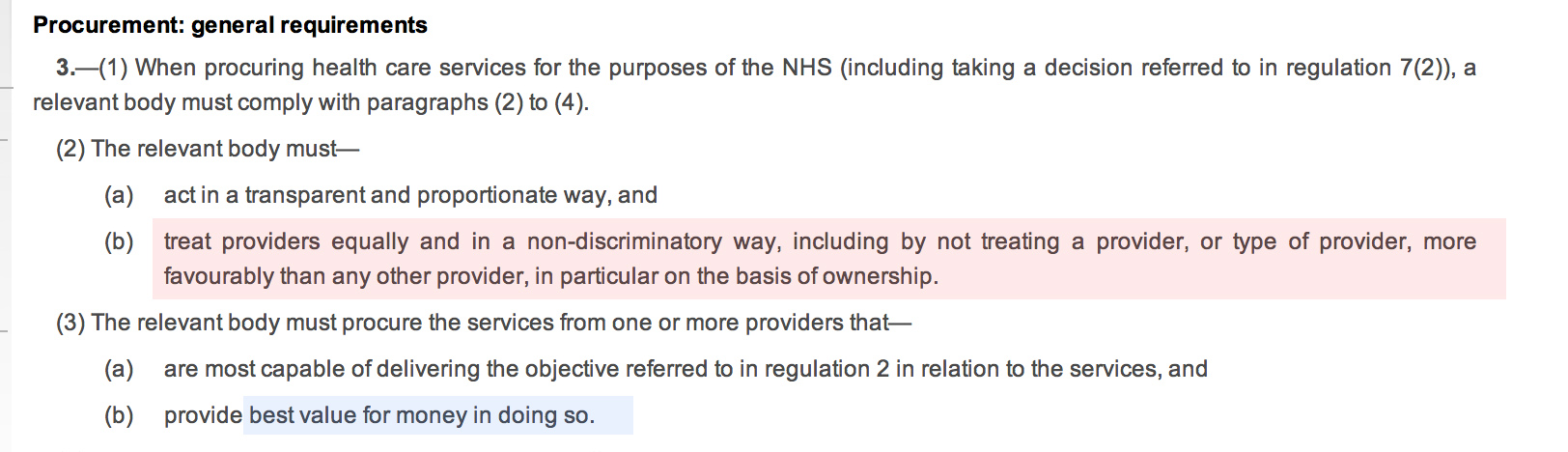

Regulation 3

3 (2)(b): “treat providers equally and in a non-discriminatory way, including by not treating aprovider, or type of provider, more favourably than any other provider, in particular onthe basis of ownership.”

It is quite unclear what this is driving at, and whether equality of providers is indeed a primary aim of the procurement process. For example, UNCITRAL model law on procurement of goods, construction and services lists this as an objective in the preamble to the law, but the Guide to Enactment suggests perhaps it is a subsidiary role. Cases such as Fabricom case (Fabricom SA v Belgium (Judgment Joined Cases C-21/03, C-34/03, 3 March 2005) are particularly helpful here.

3(b) What does “best value” in this sector indeed mean? Typical considerations such as “value for money”, as well as social, technological, environmental and various other non-price considerations, need to be discussed at some point. Again, this is essential if the law and guidance for the NHS procurement is to have adequate clarity. The point is not so much playing party-politics about grinding this legislation to a halt with an intellectual ping-pong, but it is helpful, if this clause is to be included in this statutory instrument, to understand what is in parliament’s mind for later disputes to be resolved. Presumably Monitor have begun to think about this as they hope to issue specific guidance on this?

3(4)(c) “allowing patients a choice of provider of the services” – as drafted it is unclear whether the true beneficiaries of the choice of providers are the patients themselves or CCGs (the relevant bodies); the relationship between actual patient choice and vicarious choices made by the CCGs is not addressed in this statutory instrument.

Regulation 4

Transparency for contract opportunities. This is indeed helpful to provide a rough check on how contracts are being awarded, but it has to be conceded that the public will be largely none-the-wiser as they will perform functions under the NHS logo (unless parliament requires the full identity of providers to be disclosed at the point-of-use for any particular patient.)

Regulation 6

This regulation, as drafted, is only confined to conflicts between purchasers and suppliers in the NHS, but a purpose of clauses such as this in other jurisdictions has been to address wider conflicts-of-interest, such as political donations. Although it may not be desirable to extend the ambit of discussion here too widely, some consideration should be made to how this might relate to other existant laws concerning bribery currently in force in England, for example?

Regulation 7

“Framework agreements”, which are not in fact ‘necessary’ will require in due course much greater detail if they are to be included. They certainly require, pursuant to Stroud, some scrutiny. How many suppliers will be involved in such agreements, as this relates to a complex interplay between operational efficiency, security of supply and the scope of competition? The question has to be why they have been imported from EU procurement law voluntarily, when there is actually no obligation to. It would be helpful if parliament could provide some indication of the processes and purpose of any shortlisting in the operation of these framework agreements, particularly in relation to relevant national policy considerations and disclosure of relevant criteria?

Regulations 13-17: Monitor (Investigations, declarations, directions and undertakings)

Ideally the outcome should be clear rule-based decision-making systems that limits the discretion of procuring entities. Monitor will have to have to explain this in due course, but no mention even is made of the types of issues which Monitor might have to face (e.g. fraudulent information in the bidding or execution phases, mechanisms of correcting any errors, late tenders.)

National Health Service (Procurement, patient choice and competition) Regulations 2013: what is "best value"?

The National Health Service (Procurement, patient choice and competition) Regulations 2013 is the statutory instrument which makes much more sense of the procurement regimen introduced previously. There is hardly any time to discuss the subtleties of this relatively short document which firmly thrusts the rules of the market in “competition” at the heart of NHS procurement. Many will say that these regulations existed in some form previously, but the legal intricacies of them definitely deserve full scrutiny. It sends CCGs into the coalface of making complicated procurement decisions, where the quality of tender might become significantly more important than actual “patient choice”. The procurement legislation as drafted could equally apply to procurement of virtually anything.

The entity, “the relevant body”, defined in s.1(2) as “CCG or board”, making the procurement decision according to s.3(2), and s.3(3) must make the procurement decision which does not favour any particular provider “in particular on the basis of ownership”, and which provides “best value”:

The inclusion of the reference to “ownership” is vague – it could possibly be a reference to not giving preference to NHS providers. The drafting of this Act voluntarily diminishes the rôle of the State in providing the NHS.

At first it seems that “best value” is simply to provide procurement at maximum “efficiency”, however it is widely acknowledged that there may be other benefits and outcomes of “best value” which might be hard to measure, e.g. effect locally on disadvantaged groups, possible local benefit in creating jobs. The notion of “best value” is indeed generally a thorny issue. The BIS document published in November 2011, entitled “Delivering best value through innovation: forward commitment procurement”, does however provide useful guidance. As an explanation of where it has come from, this guidance explains, “[this] comprises the European Union (EU) procurement directives, the EU Treaty principles of non-discrimination, equal-treatment and transparency, and the Governments procurement policy based on value for money”. However, the “best value” solution may not necessarily be the cheapest, and this is particularly relevant to innovative solutions (explained elsewhere in the document):

“Value for money should not be seen as a barrier to innovative solutions. Sometimes innovative offers can look more expensive in the short term, but will be a better offer in the long term. Although not listed explicitly in the Regulations, criteria involving innovative solutions may be used to determine the most economically advantageous tender, where they provide an economic advantage for the contracting authority which is linked to the product or service which is the subject matter of the contract.”

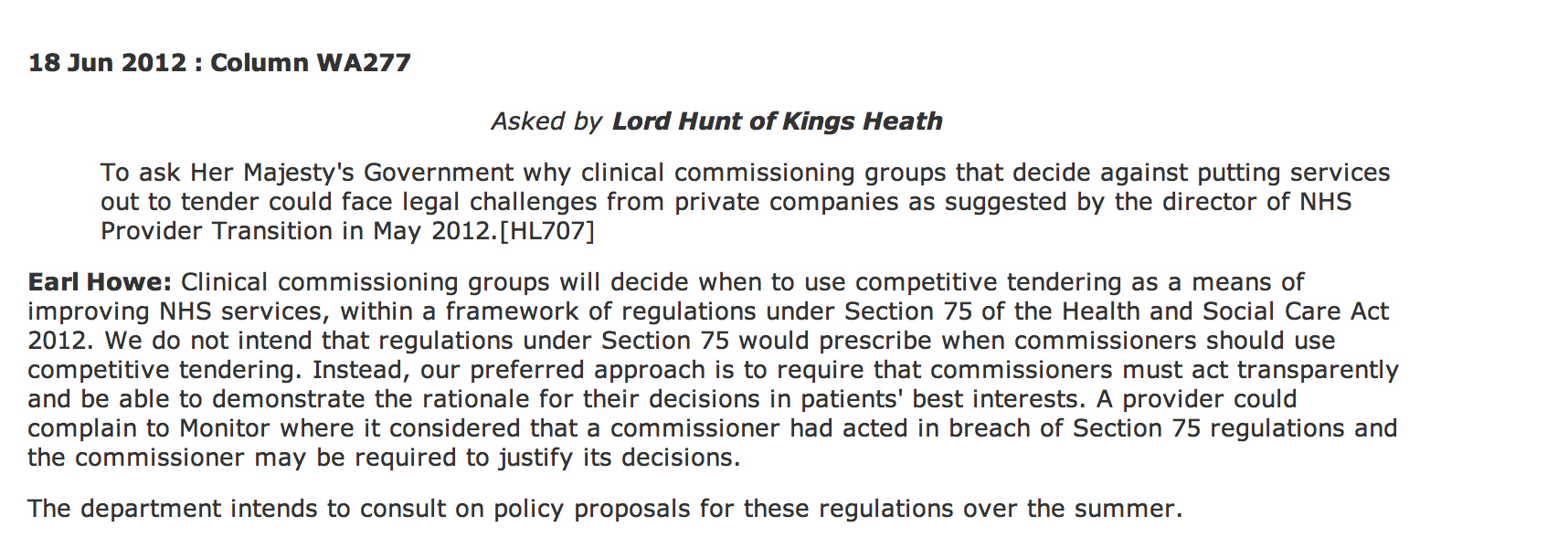

According to Hansard, Earl Howe did not intend to prescribe when ‘competitive tendering’ should exist under section 75 Health and Social Care Act (2012):

However, the problem is that Monitor can step in if the CCGs get the decision “wrong”.

Regulation 10 governs the “anti-competitive principles”. The drafting of this is ‘clunky’, with 10(2) possibly the worst example of a double negative in drafting which offends the basic legal drafting principle of clarity. The Coalition has decided to enmesh the Act full-frontally in domestic and EU competition law (as shown in regulation 10(3)), whereas before there was a lifeline for escape from competition law because of the ambiguity in whether the terms “undertaking” or “economic activity” would apply to the NHS (a downloadable document is here). This is remarkable politically in that often governments describe the EU as imposing unnecessary legislation on UK citizens; here it is almost as if the Coalition is using EU arguments about general procurement law, applicable to widgets not clinical decision-making, to justify their NHS legislation. Again, a nuance in the drafting is clearly that a NHS provider cannot be given any preference in procurement. This reflects a notion in general procurement policy, of “equal treatment of providers”, designed to encourage confidence in the process and preventing abuse of the process for undue preference to any particular suppliers. Whilst this is an objective of the “UNICTRAL model law on the procurement of goods, construction and services” in the preamble, it is thought to be a subsidiary function, and is intended to protect against overt corruption and bribery.

It is an altogether different phenomenon if Parliament had intended to offer a “comprehensive”, nationally-planned health service, and therefore wished to have a corpus of NHS providers to fulfil this aim. There are no legal limitations on Parliament. It can pass any law whatsoever. The classic example (Sir Leslie Stephens, 1882) is that Parliament could pass a law ordering the death of all blue eyed babies.

It is an altogether different phenomenon if Parliament had intended to offer a “comprehensive”, nationally-planned health service, and therefore wished to have a corpus of NHS providers to fulfil this aim. There are no legal limitations on Parliament. It can pass any law whatsoever. The classic example (Sir Leslie Stephens, 1882) is that Parliament could pass a law ordering the death of all blue eyed babies.

It is left up to Monitor to “regulate” breaches of this statutory instrument (regulations 13-17). What is striking is that the legislation appears to suggest that all “complaints” are funneled through Monitor, rather than a general health ombudsman or judicial review (presumably CCGs are still public bodies serving a public function in the public interest). The system is therefore highly dependent on Monitor running a fully explicable process, and the statutory guidance on this will be critical. We have already seen this week the judiciary ‘clearing up’ bad law from parliament. The chances are that CCGs, without adequate legal advice, will end up being powerless in querying any decisions that Monitor has judged “incorrect”, which they are fully entitled to do of their own accord according to Regulation 13(2).

The legislation, whatever the intentions of the Conservatives, Liberal Democrats, or Labour, makes it much harder for the NHS to justify procurement from NHS providers without challenges, and whose side Monitor takes on these challenges is incredibly hard to predict because of the complexities in determining what is “best value”.

The legal case for "the living wage"

It’s actually very bold, and fits in completely with the “One Nation” philosophy of Ed Miliband and Labour. It could even be one of the first Acts to be proposed by a Labour government in 2015/6, and has profound implications.

The “living wage” has a focus on the wage rate that is necessary to provide workers and their families with a basic but acceptable standard of living. It is an hourly rate set independently and updated annually, and calculated according to the basic cost of living in the UK. Employers currently can choose to pay the Living Wage on a voluntary basis; the UK Living Wage is calculated by the Centre for Research in Social Policy, but the London Living Wage is calculated by the Greater London Authority. This minimum standard of living is socially defined (and therefore varies by place and time) and is often explicitly linked to other social goals such as the fulfilment of caring responsibilities.

Uniquely for opposition policies, the Living Wage enjoys cross-party support, with public backing from the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition. That said, the main beneficiary of the living wage is the Treasury, and this is obviously critical for it to be implemented at a time of austerity (but so was the £2bn NHS reorganisation). Financial gains from the living wage will arise from higher income tax payments, higher national insurance contributions and reduced spending on in-work benefits. This has a number of important implications.

On a visit to Islington in north London last year to discuss how Labour councils across Britain have succeeded in implementing the living wage, Ed Miliband described the living wage as an idea “whose time has come”. “The next step is to help more people, including workers in the private sector, have the dignity of earning a living wage. This is one way we can begin building a One Nation economy where prosperity is fairly shared, because it is only by coming together that we can succeed as a country.”

Background

The concept of the “living wage” has roots in various cultural, religious and philiosophical traditions. The modern UK Living Wage Campaign was launched by members of London Citizens in 2001. The founders were parents in the East End of London, who wanted to remain in work, but found that despite working two minimum wage jobs they were struggling to make ends meet and were left with no time for family and community life. In 2005, following a series of successful Living Wage campaigns and growing interest from employers, the Greater London Authority established the Living Wage Unit to calculate the London Living Wage. The Living Wage campaign has since grown into a “national movement”, and Ed Miliband has often talked about how he wishes Labour to be seen as a movement and not just a political party. Local campaigns began emerging across the UK offering the opportunity to involve many more employers and lift many more thousands of families out of working poverty. In 2008 the Centre for Research in Social Policy funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation began calculating a UK wide Minimum Income Standard (MIS) figure. In 2011 Citizens UK brought together grass roots campaigners and leading employers from across the UK, working closely with colleagues on the Scottish Living Wage Campaign inparticular, to agree a standard model, for setting the UK Living Wage outside of London. At the same time, following consultation with campaigners, employers who support the Living Wage and HR specialists, Citizens UK launched the Living Wage Foundation and Living Wage Employer mark. Since 2001 the campaign has impacted over 45,000 employees and put over £210 million into the pockets of some of the lowest paid workers in the UK.

The rationale for the living wage clearly merits scrutiny. It has much popular support, and thus, as far as Labour and the Unions are concerned, consitute a clear “vote winner”. In a recent article in the Telegraph, a newspaper not known for its significant Labour sympathies, Jeremy Warner described that, “the potential negatives from such a policy are almost too numerous to list – surging inflation, higher immigration, rising unemployment, a growing black economy, and so on. These alone might appear to kill the idea stone dead. Yet all these adverse consequences could quite easily be countered, and it is a fact that the great bulk of internationally competitive business in Britain already pays living wages. It is in the low-skilled, service areas of the economy that the problem largely lies.” Interestingly, Heller Clain (2007) (J Labor Res (2008) 29:205–218) had previously argued that living wage legislation produces statistically significant differences in poverty outcomes (but that minimum wage legislation does not), with empirical evidence, and provided a clear argument concerning costs and demand how this is most likely to have arisen.

“Beyond the bottom line: the challenges and opportunities of a living wage” (IPPR)

A critical development has been the publication of “Beyond the bottom line: The challenges and opportunities of a living wage” by the IPPR, authors Matthew Pennycook and Kate Lawton (20 January 2013). This provided much detail, with The Living Wage Foundation having already established three critical functions of theirs. It offers accreditation to employers that pay the living wage, or those committed to an agreed timetable of implementation, by awarding the ‘Living Wage Employer’ mark. It also provides advice and support to employers implementing the Living Wage including best practice guides; case studies from leading employers; model procurement frameworks; access to specialist legal and HR advice. Finally, it provides a forum for leading employers to publicly back the Living Wage. We work with Principal Partners who bring financial and strategic support to the work.

Does it need an Act of parliament?

The National Minimum Wage Act 1998 created a minimum wage across the United Kingdom. It was a flagship policy of the Labour Party in the UK during its 1997 election campaign, and is still pronounced today in Labour Party circulars as an outstanding gain for ‘at least 1.5 million people’. The policy was opposed by the Conservative party at the time of implementation, who argued that it would create extra costs for businesses and would cause unemployment. The Conservative party’s current leader (and Prime Minister), David Cameron, said at the time that the minimum wage “would send unemployment straight back up”. However, in 2005, Cameron stated that “I think the minimum wage has been a success, yes. It turned out much better than many people expected, including the CBI.” It is now Conservative Party policy to support the minimum wage.

Indeed, “the living wage” has some prominent supporters.

The IPPR indeed argue that are clear reasons not to legislate for a statutory living wage including the fact that the living wage should not be seen as a replacement for the minimum wage. It there is argued that the minimum wage is based on an empirical judgment about employment effects and is agreed through a social partnership model, allowing a mandatory, statutory approach. However, the living wage reflects standards of living and prices and does not take account of employment effects. Advancing the living wage therefore requires an incremental approach, which can also bring wider benefits by mobilising low-paid workers who lack traditional forms of representation. The question for policymakers is the extent to which the state can support a campaign rooted in civil society.

The IPPR instead recommended that government amends the UK corporate governance code to require listed companies to publish the proportion and number of their staff paid below the living wage, and legislate for this if necessary. This indeed is a very sensible idea, if Ed Miliband and Labour include it as part of a raft of measures in corporate governance which could encourage ‘responsible capitalism’, which thus far has been lacking regulatory teeth. It’s possible that “the living wage” is in fact a practical mechanism of delivering “predistribution“, the thesis articulated elegantly by Professor Joseph Hacker but which people dare not mention in polite public. As part of Labour’s policy review, the party is considering ways to make the rate, which is more than £1 higher than the legal adult minimum wage, the new norm. Listed companies who do not pay the living wage could be “named and shamed” through new corporate governance proposals, and Whitehall contracts could be limited to firms that pay their workers at the new hourly rate. This would be entirely in keeping of the description of a “moral economy” advanced by Jon Cruddas discussing rebuilding Britain, a “new Jerusalem“: “Markets require reciprocity for efficiency and productivity. Together they establish trust, relationships and a sense of stewardship at the heart of transactions. It is a moral economy that can be expressed through co-operative and mutual forms of ownership, and internalised in the culture of business through employee involvement in the governance of firms. In return for their commitment to the company, employees can have a voice on salary levels, improving productivity and business strategy.”

There are though, some might say, good reasons why living wage legislation should enter the statute books in some form, corresponding to the passing of any laws in our jurisdiction. These are namely to protect an individual from harm including employment exploitation, to contribute towards a framework of the rules needed for a society to live and work together, to ensure an enforceable mechanism through which justice can been served, to “punish” people as necessary, and to maintain social order (such as prevention of poverty). It is obviously important that any laws we introduce are not incompatible with European laws, and the current indications are that the “minimum wage is (not) always incompatible with EU procurement rules. There are however obligations to treat all bidders equally, fairly and transparently and in a non-discriminatory way in any procurement process.” Specifically, the European Commission has provided clarification on the issue in 2009, stating that living wage conditions “must concern only the employees involved in the execution of the relevant contract, and may not be extended to the other employees of the contractor”. However, this perspective is to treat law as an administrative process, free from social values and judgments, as discussed by LJ Laws for example in the context of human rights. By enacting a formal law on the living wage could be a strong signal that the law is not merely an error-corrective mechanism for market values, what Prof Michael Sandel at Harvard calls ‘markets mitigating governance’ as a technocratic process done through cost benefit analyses, but that the law is in fact designed ‘for the public good’, encouraging citizenship, civic values and solidarity. Sandel conceptualises this striving for the public good as a necessary reaction to the approaches of Thatcher, Reagan and indeed New Labour, which had generated a sense of ‘market triumphalism’, but points out readily that under such administrations this had had a destructive effect on rich and poor people living further apart in society. This indeed can be easily seen in the UK with the rich becoming even richer.

One Nation Economy

Trade unions are still a significant part of the culture of UK, not least because they serve to protect workers and employees against scrupulous employers. In the trade union movement, UNISON has had noteworthy success in offering practical advice about how citizens can “win the winning wage”. Ed Miliband has made it no secret that he does not wish to see a divide between ‘private sector’ and ‘public sector’, in that we all contribute to one unitary UK economy. This has been reflected in how Miliband has provided hints about trying to make trade unions also relevant to the public sector. Encouraging a ‘living wage’ could be a way of getting more people involved in the Union movement, which Miliband has openly warned should not be seen as the “evil uncle” of Labour. The IPPR report indeed cites: “The greatest successes in securing the living wage have been made through bottom-up processes of organising and campaigning. These processes have sought to involve low-paid workers directly in the struggle to improve their own wages, as well as building broader alliances with a diverse mix of unions, faith organisations and community groups.”

As the forerunner to a ‘one nation economy’, local and regional initiatives have consolidated a number of improvements in pay for nearly 45,000 low-paid workers. In addition to the nine local authorities that have been formally accredited as living wage employers, a growing number of private sector employers have introduced living wage agreements including Barclays, KPMG, Deloitte, Linklaters and Lloyd’s of London. More widely, living wage initiatives have reshaped social norms around wages and in-work poverty and have refocused attention on the role that decent pay above the national minimum can play in raising living standards, alongside remedial redistribution through tax credits and in-work benefits. This, alongside the fact that a national minimum wage has already been acted in the UK, is significant when noted with an observation from Heller Clain 2012 (Atl Econ J (2012) 40:315–327) about how experiences of implementation of the “living wage” in the US: “Ceteris paribus, the strength of the community sentiment in support of living wage legislation may be lessened, where the state government has already adopted policies aimed at raising the incomes of the working poor. For example, there may be less motivation to enact living wage legislation where the state has already enacted a statewide minimum wage higher than the federal level.”

There are clear benefits which have been experienced by adopters of “the living wage”. An independent study of the business benefits of implementing a Living Wage policy in London found that more than 80% of employers believe that the Living Wage had enhanced the quality of the work of their staff, while absenteeism had fallen by approximately 25%. A major economic rationale is that paying UK workers a “living wage” would save the Treasury more than £2bn a year by boosting income tax receipts and reducing welfare spending, according to a joint research by the Resolution Foundation and the Institute for Public Policy Research. They found gross earnings would rise by £6.5bn if employees were paid a living wage – an estimate, above the statutory minimum hourly rate, of what workers must earn to meet basic needs. There is, additionally, a much wider elegant narrative at play here. It has been recognised by anyone other than George Osborne and his colleagues that ‘underconsumption’ has been a major factor in why the UK economy has been failing latterly (parallel with decreased levels of tax receipts, even predating the current financial crash). Indeed, starting with Malthus and Ricardo in the nineteenth century, economists had long debated the viability of ‘underconsumption’ as a cause of cyclical depressions. This is now recognised in the economic press, for example “the increasing attention to consumer demand among businessmen merged with a related trend in economics: the rise of institutional economics … A key element, though, was the conviction that economists needed detailed, quantitative, empirical studies of consumer behavior (sic) and existing markets, encompassing everything from focused psychological or sociological analyses to expansive, aggregative surveys of household income, prices, and family expenditures.” (Stapleford, Labor History, Vol. 49, No. 1, February 2008, 1–22)

The IPPR are mindful that many small and medium-sized firms are likely to struggle with the costs of implementing the living wage if a significant proportion of their staff are low paid. They recommend the government should explore using the architecture of City Deals to create ‘living wage city deals’, drawing forward future tax and benefit savings from paying local government workers the living wage and devolving this money to support private sector businesses in transitioning to the living wage. So far, two thirds of employers reported a significant impact on recruitment and retention within their organisation. 70% of employers felt that the Living Wage had increased consumer awareness of their organisation’s commitment to be an ethical employer.

One Nation Society

It’s clear that the arguments for “the living wage” are not just economic, as discussed above, but also are profoundly relevant to a sense of soldiarity and “civic duty” inherent in a “one nation society”, Living wage initiatives grounded in forms of community organising seek to increase the bargaining power of workers who lack access to more traditional forms of representation such as through trade union structures. It furthermore can easily be argued that, beyond their ability to lift wages and living standards, living wage initiatives have the potential to empower low-paid workers, many of whom lack voice and power in the workplace and in wider society. Many living wage initiatives, both in the US and UK, have sought to mobilise low earners directly rather than campaigning on their behalf, by organising workers and communities through a process described as ‘community organising’ or ‘community unionism’. Indeed, here in the UK, the Living Wage campaign was launched in 2001 by parents in East London, who were frustrated that working two minimum wage jobs left no time for family life. The causes of poverty are complex and in order to improve lives there should be a package of solutions across policy areas. The Living Wage can be part of the solution. Over 45,000 families have been lifted out of working poverty as a direct result of the Living Wage.

This is fundamentally a point to do with “cohesion” of our society. It has been patently obvious that New Labour failed monumentally on “inequality”. in its quest for market triumphalism, described above. There is a sense of Ed Miliband ‘righting a wrong’ here, in addressing the societal problem of inequality, and if Miliband can achieve this he will have succeeded in a crucial area where Blair had failed.

Conclusion

Boris Johnson appears superficially laid the groundwork for “the living wage” in London, but credit that the overall Conservative-led admininstration has led the way on employment justice can only massively dampened for a number of diverse reasons. The cross-party support is described above, but it is conceded that, in the US, “a larger population and greater local support for Democratic presidential candidates are significantly linked to a greater likelihood of adopting living wage legislation and a greater speed in adopting living wage legislation.” (Heller Clain, 2012) And yet, the “living wage” may not be necessarily partisan, although one has no idea what the Liberal Democrats wish to advance following June 2015, and would nicely fit into the framework which Ed Miliband has already provided. I expect it will be a major, if not the, major campaigning issue for Labour in 2015, and could be one of the first things an incoming Labour government would legislate for in some form. The monumental research of IPPR, the Living Wage Foundation, numerous corporates and the trade unions will have contributed greatly to the success of this initiative, as will have Ed Miliband of course.

Jon Harman and Scott Slorach: learning in the new digital age, lessons from @CollegeofLaw

An e-book is not an electronic form of a book.

I first encountered the iTutorial when I was a LLM student by distance learning by the College of Law. They are professionally presented, but I suppose that is neither here nor there. I like television news generally. The reason they work is that it’s possible to replay parts you don’t understand, and the ‘quizzes’ are very helpful to check progress.

That Jon Harman, Director of Learning at the College of Law, is interested in gaming is of no surprise. Jon is remarkably astute at environment sensing, which is the hallmark of all exceptional innovators. And “gaming”, and the approaches exemplified through the TED demonstrates, is what innovation is actually about. The success of any innovation is ultimately determined by its ease of use, how easily it can be explained, and how much people enjoying the innovation. It’s ideally meant to be an ‘easier’ way of doing thing, and the ultimate nirvana in education is for students to feel as if they’re learning for themselves in a relatively effortless manner.

This is where I feel gaming should perhaps come in, and Jon and Scott may in fact be ahead of their time. My own training was at Cambridge in neuroscience, and for a brief period in academic neurology, before I took a brief necessary detour in legal and business legal education. I am therefore concerned about how the brain works in practice. We have 1000 billion neurones, many of which make connections to one another, some functional, some not. The brain, in a way that a supercomputer might hope to be, probably has exploded in size in evolution due to the way in which combines information through ‘oscillations’ of neural activity. It’s long been of interest to Prof Horace Barlow at Cambridge, now retired but indeed Prof Colin Blakemore’s supervisor (Prof Blakemore has now head of the physiology department at Oxford for a long time), why the human brain often does functions which are subserved much ‘lower down’ in the animal kingdom, such as the fly’s eye.

The clue to this, I believe, comes from the design of the brain. The brain has rather specialised areas involved in planning, working memory, different types of factual memory, all the five senses (including especially vision), and of course movement. But sitting under the brain is of course the brainstem, and this has a fundamental role in motivation and arousal. And somewhere in the brain, probably near the front, is the part most connected with emotion (though it’s probably fair to say that the emotional state is spread quite widely throughout the entire body).

Learning is not just about learning a series of facts (or cases). Your state of mind, and indeed your mood or alertness, can both have significant effects on ‘how much you take in’, how much you are able to think on the spot, how much you are able to filter appropriate and inappropriate information, and how appropriate your solutions are. I think it is utterly reasonable for Jon and Scott to take this approach to how students can benefit from a learning process, and to think about how their learning materials can bring out the best in their students. That they have effectively come from the starting point of how the human brain actually works is of course a big honour to my own particular origin of my own learning, which are the fields of neuroscience and neurology.

Information imbalances are the heart of many recent disasters

Had certain people at the BBC known about, and acted upon, the information which is alleged about Jimmy Savile, might things have turned out differently? George Entwhistle tried to explain yesterday in the DCMS Select Committee his local audit trail of what exactly had happened with the non-report by Newsnight over these allegations.

‘Information asymmetry’ deals with the study of decisions in transactions where one party has more or better information than the other. This creates an imbalance of power in transactions which can sometimes cause the transactions to go awry, a kind of market failure in the worst case. Information asymmetry causes misinforming and is essential in every communication process. In 2001, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to George Akerlof, Michael Spence, and Joseph E. Stiglitz for their “analyses of markets with asymmetric information.” Information asymmetry models assume that at least one party to a transaction has relevant information whereas the other(s) do not. Some asymmetric information models can also be used in situations where at least one party can enforce, or effectively retaliate for breaches of, certain parts of an agreement whereas the other(s) cannot.

In adverse selection models, the ignorant party lacks information while negotiating an agreed understanding of or contract to the transaction, whereas in moral hazard the ignorant party lacks information about performance of the agreed-upon transaction or lacks the ability to retaliate for a breach of the agreement. An example of adverse selection is when people who are high risk are more likely to buy insurance, because the insurance company cannot effectively discriminate against them, usually due to lack of information about the particular individual’s risk but also sometimes by force of law or other constraints. An example of moral hazard is when people are more likely to behave recklessly after becoming insured, either because the insurer cannot observe this behavior or cannot effectively retaliate against it, for example by failing to renew the insurance.

Joseph E. Stiglitz pioneered the theory of screening, and screening is a pivotal theme in both economics and medicine. In this way the underinformed party can induce the other party to reveal their information. They can provide a menu of choices in such a way that the choice depends on the private information of the other party.

Examples of situations where the seller usually has better information than the buyer are numerous but include used-car salespeople, mortgage brokers and loan originators, stockbrokers and real estate agents. Examples of situations where the buyer usually has better information than the seller include estate sales as specified in a last will and testament, life insurance, or sales of old art pieces without prior professional assessment of their value.

This situation was first described by Kenneth J. Arrow in an article on health care in 1963. The asymmetry of information makes the relationship between patients and doctors rather different from the usual relationship between buyers and sellers. We rely upon our doctor to act in our best interests, to act as our agent. This means we are expecting our doctor to divide herself in half – on the one hand to act in our interests as the buyer of health care for us but on the other to act in her own interests as the seller of health care. In a free market situation where the doctor is primarily motivated by the profit motive, the possibility exists for doctors to exploit patients by advising more treatment to be purchased than is necessary – supplier induced demand. Traditionally, doctors’ behaviour has been controlled by a professional code and a system of licensure. In other words people can only work as doctors provided they are licensed and this in turn depends upon their acceptance of a code which makes the obligations of being an agent explicit or as Kenneth Arrow put it “The control that is exercised ordinarily by informed buyers is replaced by internalised values”

In standard civil litigation, disclosure of information takes place between the two parties in standard proceedings, a party must disclose every document of which it has control and which falls within the scope of the court’s order for disclosure. Even if a party discloses a document, the other party is not entitled to inspect the document. Of course, this disclosure procedure might have effects in producing information imbalances, where it is important to see ‘the big picture’. Such a situation is the Leveson Inquiry, ultimately looking at how activities might be better regulated if appropriate (and by whom). The communications with the former News International chief executive and the News of the World editor-turned spin doctor, Andy Coulson, were reportedly kept from the hearings into press standards after the Prime Minister sought legal advice. Labour said that David Cameron, the UK Prime Minister, must make sure that “every single communication” that passed between him and the pair be made available to the inquiry and the public. The cache runs to dozens of emails including messages sent to Mr Coulson while he was still an employee of Rupert Murdoch, according to reports. It was described by sources as containing “embarrassing” exchanges with the potential to cast further light on Mr Cameron’s relationship with two of Mr Murdoch’s most senior executives. However, Downing Street was said to have been advised that it was not “relevant” to the Leveson inquiry as the documents they contained fell outside its remit, according to The Independent.