Home » Posts tagged 'patient safety' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: patient safety

Is the answer to abject failure of medical regulation yet more regulation?

There are parallels with the discussion of whether the financial sector was too lightly regulated in the events in the global financial crash. This also happened under Labour’s watch. And Labour got a fair bit of blame for that, despite the Conservatives appearer to wish the regulation in that sector to be even “lighter”. Despite uncertainties about the number of people who actually died at Mid Staffs, for statistical reasons, there is a consensus there are clear examples of care which fell below the standard of the duty-of-care. Such breach caused damage, within an accept time period of remoteness, causing different forms of damage. The problem in this chain of the tort of regulation is that there appears to have been little in the way of damages. It is clear that the regulatory bodies have found it difficult to process their cases in a timely fashion in such a way that even some members of the medical profession and the public have found distressing and unproductive. The medical regulators are, however, fiercely concerned about their reputation, which is why any rumour that you have beeen involved in a cover up, ahead of patient safety, is potentially deadly.

There is a mild sense of panic amongst government ranks, with the introduction of a ‘Chief Inspector of Hospitals’, conducting OFSTED type assessments, and a “legal duty of candour”. It is proposed that this new legal duty might apply to institutions rather than individuals, unless Don Berwick, currently running for Governor of Massachussetts, has any better ideas in the interim. Here is the first problem; the GMC and other clinical councils take a punitive retributive approach (if not restorative), rather than rehabilitative, and Sir Robert Francis QC has emphasised that this is a wider culture malaise where it is difficult to find ‘scapegoats’. Organisations such as Cure however point to the fact that nobody appears to have taken responsibility, and are reported to have a shortlist of people who they’d like to see be in the firing line over Mid Staffs. The GMC is not in the business of blaming organisations, only individuals. In fact, its code (GMC’s “Duty of a Doctor”) is set up so that Doctors can report other Doctors to the GMC, and even report Managers to the GMC.

There is a possibility that NHS managers are not even aware of the professional code of the Doctors who comprise a key part of the workforce, but paragraph 56 of the GMC’s “Duties of a Doctor” is pivotal in demanding Doctors see their patients on the basis of clinical need. This is this clause which provides the tension with the A&E “four hour wait target”, but it is perhaps rather too late for medics to flex their professional muscles over this years after its introduction.

56. You must give priority to patients on the basis of their clinical need if these decisions are within your power. If inadequate resources, policies or systems prevent you from doing this, and patient safety, dignity or comfort may be seriously compromised, you must follow the guidance in paragraph 25b.

Paragraph 25b provides the trigger where Doctors have a duty in their Code to let their NHS manager know:

25. You must take prompt action if you think that patient safety, dignity or comfort is or may be seriously compromised. (b) If patients are at risk because of inadequate premises, equipment*or other resources, policies or systems, you should put the matter right if that is possible. You must raise your concern in line with our guidance11 and your workplace policy. You should also make a record of the steps you have taken.

And indeed following the legal trail, according to the CPS, a person holding “public office” can have committed the offence of “misconduct in a public office” if he or she does not act on such concerns, according to current guidance:

Misconduct in public office is an offence at common law triable only on indictment. It carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. It is an offence confined to those who are public office holders and is committed when the office holder acts (or fails to act) in a way that constitutes a breach of the duties of that office. The Court of Appeal has made it clear that the offence should be strictly confined. It can raise complex and sometimes sensitive issues. Prosecutors should therefore consider seeking the advice of the Principal Legal Advisor to resolve any uncertainty as to whether it would be appropriate to bring a prosecution for such an offence.

(current CPS guidance)

It is a legal point whether a NHS CEO meets the definition of a person holding “public office”. However, few will see little point in a Doctor, however Junior or Consultant, reporting a hospital manager to the GMC for lack of resources. The GMC indeed have a confidential helpline where Doctors can voice concerns about patient safety, even other colleagues, but this itself is fraught with practical considerations, such as when data are disclosed beyond confidentiality and consent, or a duty for the GMC not to encourage an avalanche of vexatious and time-consuming complaints either.

Indeed, the whole whistleblower affair has blown up because whistleblowers feel they have to make a disclosure for the purpose of patient safety in an unsupporting environment, often directly to the media, because nobody listens to them at best, or they get subject to detrimental behaviour (humiliation or bullying, for example) at worst. Clinical staff will not wish to get involved in lengthy GMC investigations about their hospital, and it would be interesting to see how many the actual number which have resulting in any form of sanction actually is. This is even amidst the backdrop that more than half of nurses believe their NHS ward or unit is dangerously understaffed, according to a recent survey, reported in February 2013. The Nursing Times conducted an online poll of nearly 600 of its readers on issues such as staffing, patient safety and NHS culture. Three-quarters had witnessed what they considered “poor” care over the past 12 months, the survey found. Understaffing in clinical wards has been identified as a cause of nurses working at a pace beyond what they are comfortable with, and the subsequent effects on patient safety are succinctly explained by Jenni Middleton (@NursingTimesEd) and colleagues in their video for the “Nursing Times Speak Out Safely” campaign.

In the same way, the cure for recession may not be more spending (this is a moot point), the answer to a failure of medical regulation may not be yet further regulation. The temptation is to add an extra layer of regulation, such as an OFHOSP body which goes round investigating hospitals, but we have already introduced a ‘Chief Inspector of Hospitals’. At worst, further regulation encourages a culture of intimidation and secrecy, and Prof Clare Gerada clearly does not believe the NHS being caught up in yet further regulation is practicable or advisable:

And yet most would agree, following Mid Staffs and the revelations over CQC at the weekend that ‘doing nothing is NOT an option’ (while conceding that a “moral panic” response cannot be appropriate either.) The fundamental problem is that this policy gives all the impression of being designed in response to a crisis, how acute medics work in ‘firefighting’. Likening patient safety to the economy, it might be more fruitful to focus attentions to the other end of the system. This is the patient safety equivalent of turning attention from redistributive (or even punitive) taxation to predistribution measures such as the living wage. Some advocates call for a greater emphasis on compassion, and reducing the number of admissions seen in the Medical Admissions Unit or A&E, but in a sense we are coming full-circle again in the underlying argument of an under-resourced ward being an unsafe one. Transplant on this a political mantra that the main parties have had divergent views about whether NHS spending is adequate now or has been adequate before, in apparent contradiction to the nearly £3bn savings which were not ploughed back into patient care. or the £2bn suddenly found for the complex implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012). The existing regulatory mechanism for complaints to be made about under-resourcing affecting patient safety is there, but the intensity of the incentive for professionals using this mechanism appears to be low. Professionals will argue that they have a professional duty to maintain patient safety regardless of yet further regulation, but professionals have reported the mission creep of deprofessionalism in the NHS for some time now. Here, the medical professions have a mechanism of holding the NHS to account, and, if adverse reports were investigated quickly and acted upon, it is possible that NHS CEOs are not overly rewarded for failure. But if this mechanism is considered unfeasible, along with a “new improved” performance management system incentivising somehow ‘whistleblowing’, it’s back to the drawing board yet again.

It was honour to speak to a group of suspended Doctors on the Practitioner Health Programme this morning about recovery

It was a real honour and privilege to be invited to give a talk to a group of medical Doctors who were currently suspended on the GMC Medical Register this morning (in confidence). I gave a talk for about thirty minutes, and took questions afterwards. I have enormous affection for the medical profession in fact, having obtained a First at Cambridge in 1996, and also produced a seminal paper in dementia published in a leading journal as part of my Ph.D. there. I have had nothing to do with the medical profession for several years now, apart from volunteering part-time for two medical charities in London which I no longer do.

I currently think patient safety is paramount, and Doctors with addiction problems often do not realise the effect the negative impact of their addiction on their performance. No regulatory authority can do ‘outreach’, otherwise it would be there forever, in the same way that Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous do not actively go out looking for people with addiction problems. I personally have doubts about the notion of a ‘high functioning addict’, as the addict is virtually oblivious to all the distress and débris caused by their addiction; the impact on others is much worse than on the individual himself, who can lack insight and can be in denial. Insight is something that is best for others to judge.

However, I have now been in recovery for 72 months, with things having come to a head when I was admitted in August 2007 having had an epileptic seizure and asystolic cardiac arrest. Having woken up on the top floor of the Royal Free Hospital in pitch darkness, I had to cope with recovery from alcoholism (I have never been addicted to any other drugs), and newly-acquired physical disability. I in fact could neither walk nor talk. Nonetheless, I am happy as I live with my mum in Primrose Hill, have never had any regular salaried employment since my coma in the summer of 2007, received scholarships to do my MBA and legal training (otherwise my life would have become totally unsustainable financially apart from my disability living allowance which I use for my mobility and living). I am also very proud to have completed my Master of Law with a commendation in January 2011. My greatest achievement of all has been sustaining my recovery, and my talk went very well this morning.

The message I wished to impart that personal health and recovery is much more important than temporary abstinence, ‘getting the certificate’ and carrying on with your career if you have a genuine problem. People in any discipline will often not seek help for addiction, as they worry about their training record. Some will even not enlist with a G.P., in case the GP reports them to a regulatory authority. I discussed how I had a brilliant doctor-patient relationship with my own G.P. and how the support from the Solicitors Regulation Authority (who allowed me unconditionally to do the Legal Practice Course after an extensive due diligence) had been vital, but I also fielded questions on the potential impact of stigma of stigma in the regulatory process as a barrier-to-recovery.

I gave an extensive list of my own ‘support network’, which included my own G.P., psychiatrist, my mum, other family and friends, the Practitioner Health Programme, and ‘After Care’ at my local hospital.

The Practitioner Health Programme, supported by the General Medical Council, describes itself as follows:

The Practitioner Health Programme is a free, confidential service for doctors and dentists living in London who have mental or physical health concerns and/or addiction problems.

Any medical or dental practitioner can use the service, where they have

• A mental health or addiction concern (at any level of severity) and/or

• A physical health concern (where that concern may impact on the practitioner’s performance.)

I was asked which of these had helped me the most, which I thought was a very good question. I said that it was not necessarily the case that a bigger network was necessarily better, but it did need individuals to be open and truthful with you if things began to go wrong. It gave me a chance to outline the fundamental conundrum of recovery; it’s impossible to go into recovery on your own (for many this will mean going to A.A. or other meetings, and discussing recovery with close friends), but likewise the only person who can help you is yourself (no number of expensive ‘rehabs’ will on their own provide you with the ‘cure’.) This is of course a lifelong battle for me, and whilst I am very happy now as things have moved on for me, I hope I may at last help others who need help in a non-professional capacity.

Best wishes, Shibley

My talk [ edited ]

It was honour to speak to a group of suspended Doctors on the Practitioner Health Programme this morning about recovery

It was a real honour and privilege to be invited to give a talk to a group of medical Doctors who were currently suspended on the GMC Medical Register this morning (in confidence). I gave a talk for about thirty minutes, and took questions afterwards. I have enormous affection for the medical profession in fact, having obtained a First at Cambridge in 1996, and also produced a seminal paper in dementia published in a leading journal as part of my Ph.D. there. I have had nothing to do with the medical profession for several years now, apart from volunteering part-time for two medical charities in London which I no longer do.

I think patient safety is paramount, and Doctors with addiction problems often do not realise the effect the negative impact of their addiction on their performance. No regulatory authority can do ‘outreach’, otherwise it would be there forever, in the same way that Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous do not actively go out looking for people with addiction problems. I personally have doubts about the notion of a ‘high functioning addict’, as the addict is virtually oblivious to all the distress and débris caused by their addiction; the impact on others is much worse than on the individual himself, who can lack insight and can be in denial. Insight is something that is best for others to judge.

However, I have now been in recovery for 72 months, with things having come to a head when I was admitted in August 2007 having had an epileptic seizure and asystolic cardiac arrest. Having woken up on the top floor of the Royal Free Hospital in pitch darkness, I had to cope with recovery from alcoholism (I have never been addicted to any other drugs), and newly-acquired physical disability. I in fact could neither walk nor talk. Nonetheless, I am happy as I live with my mum in Primrose Hill, have never had any regular salaried employment since my coma in the summer of 2007, received scholarships to do my MBA and legal training (otherwise my life would have become totally unsustainable financially apart from my disability living allowance which I use for my mobility and living). I am also very proud to have completed my Master of Law with a commendation in January 2011. My greatest achievement of all has been sustaining my recovery, and my talk went very well this morning.

The message I wished to impart that personal health and recovery is much more important than temporary abstinence, ‘getting the certificate’ and carrying on with your career if you have a genuine problem. People in any discipline will often not seek help for addiction, as they worry about their training record. Some will even not enlist with a G.P., in case the GP reports them to a regulatory authority. I discussed how I had a brilliant doctor-patient relationship with my own G.P. and how the support from the Solicitors Regulation Authority (who allowed me unconditionally to do the Legal Practice Course after an extensive due diligence) had been vital, but I also fielded questions on the potential impact of stigma of stigma in the regulatory process as a barrier-to-recovery.

I gave an extensive list of my own ‘support network’, which included my own G.P., psychiatrist, my mum, other family and friends, the Practitioner Health Programme, and ‘After Care’ at my local hospital.

The Practitioner Health Programme, supported by the General Medical Council, describes itself as follows:

The Practitioner Health Programme is a free, confidential service for doctors and dentists living in London who have mental or physical health concerns and/or addiction problems.

Any medical or dental practitioner can use the service, where they have

• A mental health or addiction concern (at any level of severity) and/or

• A physical health concern (where that concern may impact on the practitioner’s performance.)

I was asked which of these had helped me the most, which I thought was a very good question. I said that it was not necessarily the case that a bigger network was necessarily better, but it did need individuals to be open and truthful with you if things began to go wrong. It gave me a chance to outline the fundamental conundrum of recovery; it’s impossible to go into recovery on your own (for many this will mean going to A.A. or other meetings, and discussing recovery with close friends), but likewise the only person who can help you is yourself (no number of expensive ‘rehabs’ will on their own provide you with the ‘cure’.) This is of course a lifelong battle for me, and whilst I am very happy now as things have moved on for me, I hope I may at last help others who need help in a non-professional capacity.

Best wishes, Shibley

My talk [ edited ]

Is the pilot always to blame if things go wrong in a safety-compliant plane in the NHS?

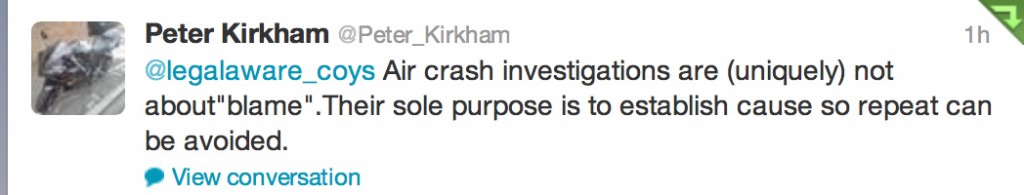

The “purpose” of an air plane crash investigation is apparently as set out in the tweet below:

It seems appropriate to extend the “lessons from the aviation industry” in approaching the issue of how to approach blame and patient safety in the NHS. Dr Kevin Fong, NHS consultant at UCHL NHS Foundation Trust in anaesthetics amongst many other specialties, highlighted this week in his excellent BBC Horizon programme how an abnormal cognitive reaction to failure can often make management of patient safety issues in real time more difficult. Approaches to management in the real world have long made the distinction between “managers” and “leaders” and it is useful to consider what the rôle of both types of NHS employees might be, particularly given the political drive for ‘better leadership’ in the NHS.

In corporates, reasons for ‘denial about failure’ are well established (e.g. Richard Farson and Ralph Keyes writing in the Harvard Business Review, August 2002):

“While companies are beginning to accept the value of failure in the abstract-at the level of corporate policies, processes, and practices-it’s an entirely different matter at the personal level. Everyone hates to fail. We assume, rationally or not, that we’ll suffer embarrassment and a loss of esteem and stature. And nowhere is the fear of failure more intense and debilitating than in the competitive world of business, where a mistake can mean losing a bonus, a promotion, or even a job.”

Farson and Keyes (2011) identify early-on for potential benefits of “failure-tolerant leaders”:

“Of course, there are failures and there are failures. Some mistakes are lethal-producing and marketing a dysfunctional car tire, for example. At no time can management be casual about issues of health and safety. But encouraging failure doesn’t mean abandoning supervision, quality control, or respect for sound practices, just the opposite. Managing for failure requires executives to be more engaged, not less. Although mistakes are inevitable when launching innovation initiatives, management cannot abdicate its responsibility to assess the nature of the failures. Some are excusable errors; others are simply the result of sloppiness. Those willing to take a close look at what happened and why can usually tell the difference. Failure-tolerant leaders identify excusable mistakes and approach them as outcomes to be examined, understood, and built upon. They often ask simple but illuminating questions when a project falls short of its goals:

- Was the project designed conscientiously, or was it carelessly organized?

- Could the failure have been prevented with more thorough research or consultation?

- Was the project a collaborative process, or did those involved resist useful input from colleagues or fail to inform interested parties of their progress?

- Did the project remain true to its goals, or did it appear to be driven solely by personal interests?

- Were projections of risks, costs, and timing honest or deceptive?

- Were the same mistakes made repeatedly?”

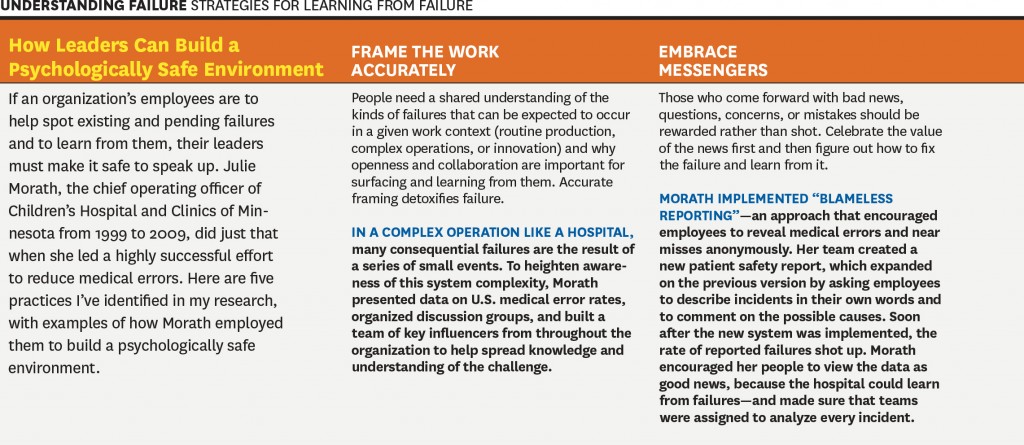

It is incredibly difficult to identify who is ‘accountable’ or ‘responsible’ for potential failures in patient safety in the NHS: is it David Nicholson, as widely discussed, or any of the Secretaries of States for health? There is a mentality in the popular media to try to find someone who is responsible for this policy, and potentially the need to attach blame can be a barrier to learning from failure. For example, Amy C Edmondson also in the Harvard Business Review writes:

“The wisdom of learning from failure is incontrovertible. Yet organizations that do it well are extraordinarily rare. This gap is not due to a lack of commitment to learning. Managers in the vast majority of enterprises that I have studied over the past 20 years—pharmaceutical, financial services, product design, telecommunications, and construction companies, hospitals, and NASA’s space shuttle program, among others—genuinely wanted to help their organizations learn from failures to improve future performance. In some cases they and their teams had devoted many hours to after-action reviews, post mortems, and the like. But time after time I saw that these painstaking efforts led to no real change. The reason: Those managers were thinking about failure the wrong way.”

Learning from failure is of course extremely important in the corporate sectors, and some of the lessons might be productively transposed to the NHS too. This is from the same article:

However, is this is a cultural issue or a leadership issue? Michael Leonard and Allan Frankel in an excellent “thought paper” from the Health Foundation begin to address this issue:

“A robust safety culture is the combination of attitudes and behaviours that best manages the inevitable dangers created when humans, who are inherently fallible, work in extraordinarily complex environments. The combination, epitomised by healthcare, is a lethal brew.

Great leaders know how to wield attitudinal and behavioural norms to best protect against these risks. These include: 1) psychological safety that ensures speaking up is not associated with being perceived as ignorant, incompetent, critical or disruptive (leaders must create an environment where no one is hesitant to voice a concern and caregivers know that they will be treated with respect when they do); 2) organisational fairness, where caregivers know that they are accountable for being capable, conscientious and not engaging in unsafe behaviour, but are not held accountable for system failures; and 3) a learning system where engaged leaders hear patients and front-line caregivers’ concerns regarding defects that interfere with the delivery of safe care, and promote improvement to increase safety and reduce waste. Leaders are the keepers and guardians of these attitudinal norms and the learning system.”

Whatever the debate about which measure accurately describes mortality in the NHS, it is clear that there is potentially an issue in some NHS trusts on a case-by-case issue (see for example this transcript of “File on 4″‘s “Dangerous hospitals”), prompting further investigation through Sir Bruce Keogh’s “hit list“) Whilst headlines stating dramatic statistics are definitely unhelpful, such as “Another nine hospital trusts with suspiciously high death rates are to be investigated, it was revealed today”, there is definitely something to investigate here.

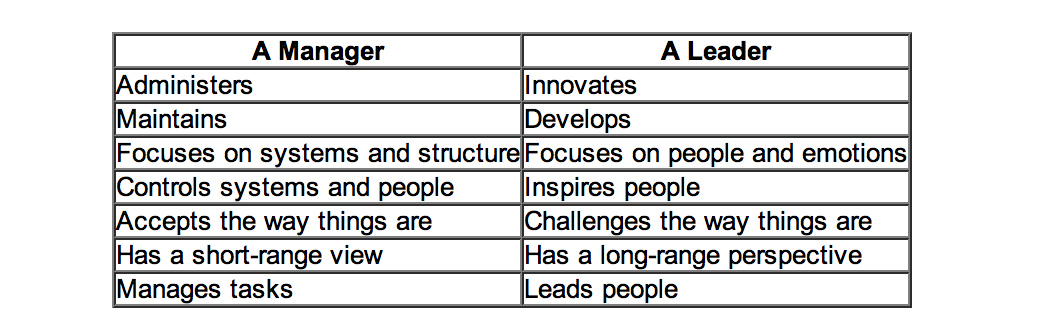

Is this even a leadership or management thing? One of the most famous distinctions between managers and leaders was made by Warren Bennis, a professor at the University of Southern California. Bennis famously believes that, “Managers do things right but leaders do the right things”. It is argued that doing the right thing, however, is a much more philosophical concept and makes us think about the future, about vision and dreams: this is a trait of a leader. Bennis goes on to compare these thoughts in more detail, the table below is based on his work:

Differences between managers and leaders

Indeed, people are currently scrabbling around now for “A new style of leadership for the NHS” as described in this Guardian article here.

Is patient safety predominantly a question of “teamwork”?

Amalberti and colleagues (Amalberti et al., 2005) make some interesting observations about teamwork and professionalism:

“A growing movement toward educating health care professionals in teamwork and strict regulations have reduced the autonomy of health care professionals and thereby improved safety in health care. But the barrier of too much autonomy cannot be overcome completely when teamwork must extend across departments or geographic areas, such as among hospital wards or departments. For example, unforeseen personal or technical circumstances sometimes cause a surgery to start and end well beyond schedule. The operating room may be organized in teams to face such a change in plan, but the ward awaiting the patient’s return is not part of the team and may be unprepared. The surgeon and the anesthesiologist must adopt a much broader representation of the system that includes anticipation of problems for others and moderation of goals, among other factors. Systemic thinking and anticipation of the consequences of processes across depart- ments remain a major challenge.”

Weisner and colleagues (Weisner et al., 2010) have indeed observed that:

“Medical teams are generally autocratic, with even more extreme authority gradient in some developing countries, so there is little opportunity for error catching due to cross-check. A checklist is ‘a formal list used to identify, schedule, compare or verify a group of elements or… used as a visual or oral aid that enables the user to overcome the limitations of short-term human memory’. The use of checklists in health care is increasingly common. One of the first widely publicized checklists was for the insertion of central venous catheters. This checklist, in addition to other team-building exercises, helped significantly decrease the central line infection rate per 1000 catheter days from 2.7 at baseline to zero.”

M. van Beuzekom and colleagues (van Beuzekom et al., 2013) and colleagues, additionally, describe an interesting example from the Netherlands. Teams in healthcare are co-incidentally formed, similar to airline crews. The teams consist of members of several different disciplines that work together for that particular operation or the whole operating day. This task-oriented team model with high levels of specialization has historically focused on technical expertise and performance of members with little emphasis on interpersonal behaviour and teamwork. In this model, communication is informally learned and developed with experience. This places a substantial demand on the non-clinical skills of the team members, especially in high-demand situations like crises.

Bleetman and colleagues (Bleetman et al., 2011) mention that, “whenever aviation is cited as an example of effective team management to the healthcare audience, there is an almost audible sigh.” Debriefing is the final teamwork behaviour that closes the loop and facilitates both teamwork and learning. Sustaining these team behaviours depends on the ability to capture information from front-line caregivers and take action. In aviation, briefings are a ‘must-do’ are not an optional extra. They are performed before every take-off and every landing. They serve to share the plan for what should happen, what could happen, to distribute the workload efficiently and to prevent and manage unexpected problems. So how could we fit briefings into emergency medicine? Even though staff may be reluctant to leave the computer screen in a busy department, it is likely to be worth assembling the team for a few minutes to provide some order and structure to a busy department and plan the shift.

Briefing points apparently could cover:

- The current situation

- Who is present on the team and their experience level

- Who is best suited to which patients and crises so that the most effective deployment of team members occurs rathe than a haphazard arrangement

- The identification of possible traps and hazards such as staff shortages ahead of time

- Shared opinions and concerns.

The authors describe that, “at the end of the shift a short debriefing is useful to thank staff and identify what went well and what did not. Positive outcomes and initiatives can be agreed.”

Is patient safety predominantly a question of “leadership”?

The literature identifies that overall team members are important who have a good sense of “situational awareness” about the patient safety issue evolving around them. However, it is being increasingly recognised that to provide effective clinical leadership in such situations, the “team leader” needs to develop a certain set of non-clinical skills. This situation demands more than currency in advance paediatric life support or advanced trauma life support; it requires the confidence (underpinned by clinical knowledge) to guide, lead and assimilate information from multiple sources to make quick and sound decisions. The team leader is bound to encounter different personalities, seniority, expectations and behaviours from members of the team, each of whom will have their own insecurities, personality, anxieties and ego.

Amalberti and colleagues (Amalberti et al., 2005) begin to develop a complex narrative on the relationship between leadership and management (and the patients whom “they serve”):

“Systems have a definite tendency toward constraint. For example, civil aviation restricts pilots in terms of the type of plane they may fly, limits operations on the basis of traffic and weather conditions, and maintains a list of the minimum equipment required before an aircraft can fly. Line pilots are not allowed to exceed these limits even when they are trained and competent. Hence, the flight (product) offered to the client is safe, but it is also often delayed, rerouted, or cancelled. Would health care and patients be willing to follow this trend and reject a surgical procedure under circumstances in which the risks are outside the boundaries of safety? Physicians already accept individual limits on the scope of their maximum performance in the privileging process; societal demand, workforce strategies, and competing demands on leadership will undermine this goal. A hard-line policy may conflict with ethical guidelines that recommend trying all possible measures to save individual patients.”

Conclusion

Even if one decides to blame the pilot of the plane, one has to wonder the extent to which the CEO of the entire airplane organisation might to be blame. The question for the NHS has become: who exactly is the pilot of plane? Is it the CEO of the NHS Foundation Trust, the CEO of NHS England, or even someone else? And rumbling on in this debate is whether the plane has definitely crashed: some relatives of passengers are overall in absolutely no doubt that the plane has crashed, and they indeed have to live with the wreckage daily. Politicians have then to decide whether the pilot ought to resign (has he done something fundamentally wrong?) or has there been something fundamentally much more distal which has gone wrong with his cockpit crew for example? And, whichever figurehead is identified if at all for any problems in this particular flights, should the figurehead be encouraged to work in a culture where problems in flying his plane have been identified and corrected safely? And finally is this is a lone airplane which has crashed (or not crashed), and are there other reports of plane crashes or near-misses to come?

References

Learning from failure

Farson, R. and Keyes, R. (2002) The Failure Tolerant Leader, Harvard Bus Rev, 80(8):64-71, 148.

Edmondson, A. Strategies for learning from failure, Harvard Bus Rev, ;89(4):48-55, 137.

Patient safety

Amalbert, R., Auroy, Y., Berwick, D., and Barach, P. (2005) Five System Barriers to Achieving Ultrasafe Health Care, Ann Intern Med, 142, pp. 756-764.

Bleetman, A., Sanusi, S., Dale, T., and Brace, S.(2012) Human factors and error prevention in emergency medicine, Emerg Med J, 29, pp. 389e393. d

Federal Aviation Administration, Section 12: Aircraft Checklists for 14 CFR Parts 121/135 iFOFSIMSF.

Pronovost, P., Needham, D., Berenholtz, S., Sinopoli, D., Chu, H., Cosgrove, S., Sexton, B., Hyzy, R., Welsh, R., Roth, G., Bander, J., Kepros, J., and Goeschel, C. (2006) An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU, N Engl J Med, 355, pp. 2725–32.

van Beuzekom, M., Boer, F., Akerboom, S., and Dahan, A. (2013) Perception of patient safety differs by clinical area and discipline, British Journal of Anaesthesia, 110 (1), pp. 107–14.

Weisner, T.G., Haynes, A.B., Lashoher, A., Dziekman, G., Moorman, D.J., Berry, W.R., and Gawande, A.A. (2010) Perspectives in quality: designing the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 22(5), pp. 365–370.

Is it appropriate to blame the pilot of the NHS safety-compliant plane?

Please contact @legalaware if you would like to tweet constructively with the author about the ideas contained herewith.

The “purpose” of an air plane crash investigation is apparently as set out in the tweet below:

It seems appropriate to extend the “lessons from the aviation industry” in approaching the issue of how to approach blame and patient safety in the NHS. Dr Kevin Fong, NHS consultant at UCHL NHS Foundation Trust in anaesthetics amongst many other specialties, highlighted this week in his excellent BBC Horizon programme how an abnormal cognitive reaction to failure can often make management of patient safety issues in real time more difficult. Approaches to management in the real world have long made the distinction between “managers” and “leaders” and it is useful to consider what the rôle of both types of NHS employees might be, particularly given the political drive for ‘better leadership’ in the NHS.

In corporates, reasons for ‘denial about failure’ are well established (e.g. Richard Farson and Ralph Keyes writing in the Harvard Business Review, August 2002):

“While companies are beginning to accept the value of failure in the abstract-at the level of corporate policies, processes, and practices-it’s an entirely different matter at the personal level. Everyone hates to fail. We assume, rationally or not, that we’ll suffer embarrassment and a loss of esteem and stature. And nowhere is the fear of failure more intense and debilitating than in the competitive world of business, where a mistake can mean losing a bonus, a promotion, or even a job.”

Farson and Keyes (2011) identify early-on for potential benefits of “failure-tolerant leaders”:

“Of course, there are failures and there are failures. Some mistakes are lethal-producing and marketing a dysfunctional car tire, for example. At no time can management be casual about issues of health and safety. But encouraging failure doesn’t mean abandoning supervision, quality control, or respect for sound practices, just the opposite. Managing for failure requires executives to be more engaged, not less. Although mistakes are inevitable when launching innovation initiatives, management cannot abdicate its responsibility to assess the nature of the failures. Some are excusable errors; others are simply the result of sloppiness. Those willing to take a close look at what happened and why can usually tell the difference. Failure-tolerant leaders identify excusable mistakes and approach them as outcomes to be examined, understood, and built upon. They often ask simple but illuminating questions when a project falls short of its goals:

- Was the project designed conscientiously, or was it carelessly organized?

- Could the failure have been prevented with more thorough research or consultation?

- Was the project a collaborative process, or did those involved resist useful input from colleagues or fail to inform interested parties of their progress?

- Did the project remain true to its goals, or did it appear to be driven solely by personal interests?

- Were projections of risks, costs, and timing honest or deceptive?

- Were the same mistakes made repeatedly?”

It is incredibly difficult to identify who is ‘accountable’ or ‘responsible’ for potential failures in patient safety in the NHS: is it David Nicholson, as widely discussed, or any of the Secretaries of States for health? There is a mentality in the popular media to try to find someone who is responsible for this policy, and potentially the need to attach blame can be a barrier to learning from failure. For example, Amy C Edmondson also in the Harvard Business Review writes:

“The wisdom of learning from failure is incontrovertible. Yet organizations that do it well are extraordinarily rare. This gap is not due to a lack of commitment to learning. Managers in the vast majority of enterprises that I have studied over the past 20 years—pharmaceutical, financial services, product design, telecommunications, and construction companies, hospitals, and NASA’s space shuttle program, among others—genuinely wanted to help their organizations learn from failures to improve future performance. In some cases they and their teams had devoted many hours to after-action reviews, post mortems, and the like. But time after time I saw that these painstaking efforts led to no real change. The reason: Those managers were thinking about failure the wrong way.”

Learning from failure is of course extremely important in the corporate sectors, and some of the lessons might be productively transposed to the NHS too. This is from the same article:

However, is this is a cultural issue or a leadership issue? Michael Leonard and Allan Frankel in an excellent “thought paper” from the Health Foundation begin to address this issue:

“A robust safety culture is the combination of attitudes and behaviours that best manages the inevitable dangers created when humans, who are inherently fallible, work in extraordinarily complex environments. The combination, epitomised by healthcare, is a lethal brew.

Great leaders know how to wield attitudinal and behavioural norms to best protect against these risks. These include: 1) psychological safety that ensures speaking up is not associated with being perceived as ignorant, incompetent, critical or disruptive (leaders must create an environment where no one is hesitant to voice a concern and caregivers know that they will be treated with respect when they do); 2) organisational fairness, where caregivers know that they are accountable for being capable, conscientious and not engaging in unsafe behaviour, but are not held accountable for system failures; and 3) a learning system where engaged leaders hear patients and front-line caregivers’ concerns regarding defects that interfere with the delivery of safe care, and promote improvement to increase safety and reduce waste. Leaders are the keepers and guardians of these attitudinal norms and the learning system.”

Whatever the debate about which measure accurately describes mortality in the NHS, it is clear that there is potentially an issue in some NHS trusts on a case-by-case issue (see for example this transcript of “File on 4″‘s “Dangerous hospitals”), prompting further investigation through Sir Bruce Keogh’s “hit list“) Whilst headlines stating dramatic statistics are definitely unhelpful, such as “Another nine hospital trusts with suspiciously high death rates are to be investigated, it was revealed today”, there is definitely something to investigate here.

Is this even a leadership or management thing? One of the most famous distinctions between managers and leaders was made by Warren Bennis, a professor at the University of Southern California. Bennis famously believes that, “Managers do things right but leaders do the right things”. It is argued that doing the right thing, however, is a much more philosophical concept and makes us think about the future, about vision and dreams: this is a trait of a leader. Bennis goes on to compare these thoughts in more detail, the table below is based on his work:

Indeed, people are currently scrabbling around now for “A new style of leadership for the NHS” as described in this Guardian article here.

Is patient safety predominantly a question of “teamwork”?

Amalberti et al. (2005) make some interesting observations about teamwork and professionalism:

“A growing movement toward educating health care professionals in teamwork and strict regulations have reduced the autonomy of health care professionals and thereby improved safety in health care. But the barrier of too much autonomy cannot be overcome completely when teamwork must extend across departments or geographic areas, such as among hospital wards or departments. For example, unforeseen personal or technical circumstances sometimes cause a surgery to start and end well beyond schedule. The operating room may be organized in teams to face such a change in plan, but the ward awaiting the patient’s return is not part of the team and may be unprepared. The surgeon and the anesthesiologist must adopt a much broader representation of the system that includes anticipation of problems for others and moderation of goals, among other factors. Systemic thinking and anticipation of the consequences of processes across depart- ments remain a major challenge.”

Weisner et al. (2010) have indeed observed that:

“Medical teams are generally autocratic, with even more extreme authority gradient in some developing countries, so there is little opportunity for error catching due to cross-check. A checklist is ‘a formal list used to identify, schedule, compare or verify a group of elements or… used as a visual or oral aid that enables the user to overcome the limitations of short-term human memory’. The use of checklists in health care is increasingly common. One of the first widely publicized checklists was for the insertion of central venous catheters. This checklist, in addition to other team-building exercises, helped significantly decrease the central line infection rate per 1000 catheter days from 2.7 at baseline to zero.”

M. van Beuzekom et al. (2013) and colleagues, additionally, describe an interesting example from the Netherlands. Teams in healthcare are co-incidentally formed, similar to airline crews. The teams consist of members of several different disciplines that work together for that particular operation or the whole operating day. This task-oriented team model with high levels of specialization has historically focused on technical expertise and performance of members with little emphasis on interpersonal behaviour and teamwork. In this model, communication is informally learned and developed with experience. This places a substantial demand on the non-clinical skills of the team members, especially in high-demand situations like crises.

Bleetman et al. (2011) mention that, “whenever aviation is cited as an example of effective team management to the healthcare audience, there is an almost audible sigh.” Debriefing is the final teamwork behaviour that closes the loop and facilitates both teamwork and learning. Sustaining these team behaviours depends on the ability to capture information from front-line caregivers and take action. In aviation, briefings are a ‘must-do’ are not an optional extra. They are performed before every take-off and every landing. They serve to share the plan for what should happen, what could happen, to distribute the workload efficiently and to prevent and manage unexpected problems. So how could we fit briefings into emergency medicine? Even though staff may be reluctant to leave the computer screen in a busy department, it is likely to be worth assembling the team for a few minutes to provide some order and structure to a busy department and plan the shift.

Briefing points could cover:

- The current situation

- Who is present on the team and their experience level

- Who is best suited to which patients and crises so that the most effective deployment of team members occurs rathe than a haphazard arrangement

- The identification of possible traps and hazards such as staff shortages ahead of time

- Shared opinions and concerns.

The authors describe that, “at the end of the shift a short debriefing is useful to thank staff and identify what went well and what did not. Positive outcomes and initiatives can be agreed.”

Is patient safety predominantly a question of “leadership”?

The literature identifies that overall team members are important who have a good sense of “situational awareness” about the patient safety issue evolving around them. However, it is being increasingly recognised that to provide effective clinical leadership in such situations, the “team leader” needs to develop a certain set of non-clinical skills. This situation demands more than currency in advance paediatric life support or advanced trauma life support; it requires the confidence (underpinned by clinical knowledge) to guide, lead and assimilate information from multiple sources to make quick and sound decisions. The team leader is bound to encounter different personalities, seniority, expectations and behaviours from members of the team, each of whom will have their own insecurities, personality, anxieties and ego.

Amalberti et al. (2005) begin to develop a complex narrative on the relationship between leadership and management (and the patients whom “they serve”):

“Systems have a definite tendency toward constraint. For example, civil aviation restricts pilots in terms of the type of plane they may fly, limits operations on the basis of traffic and weather conditions, and maintains a list of the minimum equipment required before an aircraft can fly. Line pilots are not allowed to exceed these limits even when they are trained and competent. Hence, the flight (product) offered to the client is safe, but it is also often delayed, rerouted, or cancelled. Would health care and patients be willing to follow this trend and reject a surgical procedure under circumstances in which the risks are outside the boundaries of safety? Physicians already accept individual limits on the scope of their maximum performance in the privileging process; societal demand, workforce strategies, and competing demands on leadership will undermine this goal. A hard-line policy may conflict with ethical guidelines that recommend trying all possible measures to save individual patients.”

Conclusion

Even if one decides to blame the pilot of the plane, one has to wonder the extent to which the CEO of the entire airplane organisation might to be blame. The question for the NHS has become: who exactly is the pilot of plane? Is it the CEO of the NHS Foundation Trust, the CEO of NHS England, or even someone else? And rumbling on in this debate is whether the plane has definitely crashed: some relatives of passengers are overall in absolutely no doubt that the plane has crashed, and they indeed have to live with the wreckage daily. Politicians have then to decide whether the pilot ought to resign (has he done something fundamentally wrong?) or has there been something fundamentally much more distal which has gone wrong with his cockpit crew for example? And, whichever figurehead is identified if at all for any problems in this particular flights, should the figurehead be encouraged to work in a culture where problems in flying his plane have been identified and corrected safely? And finally is this is a lone airplane which has crashed (or not crashed), and are there other reports of plane crashes or near-misses to come?

References

Learning from failure

Richard Farson and Ralph Keyes. The Failure Tolerant Leader. Harvard Business Review: August 2002.

Amy Edmondson. Strategies for learning from failure. Harvard Business Review: April 2011.

Patient safety

Amalbert, R, Auroy, Y, Berwick, D, Barach, P. Five System Barriers to Achieving Ultrasafe Health Care Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:756-764.

Bleetman, A, Sanusi, S, Dale, T, Brace. (2012) Human factors and error prevention in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J 2012;29:389e393. doi:10.1136/emj.2010.107698

Federal Aviation Administration. Section 12: Aircraft Checklists for 14 CFR Parts 121/135 iFOFSIMSF.

Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S et al. (2006) An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med 355:2725–32.

van Beuzekom, M, Boer, F, Akerboom, S, Dahan, A. (2013) Perception of patient safety differs by clinical area and discipline. British Journal of Anaesthesia 110 (1): 107–14 (2013)

Weisner, TG, Haynes, AB, Lashoher, A, Dziekman, G, Moorman, DJ, Berry, WR, Gawande, AA. Perspectives in quality: designing the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist. (2010) International Journal for Quality in Health Care Volume 22, Number 5: pp. 365–370

A failure of leadership and management: toxic cultures, ENRON and the Francis Report

Robert Francis has an incredibly difficult task. It is difficult for people who have not qualified, even managers and leaders of healthcare think tanks, to understand how this situation has arisen. Being a senior lawyer, his approach will necessarily involve “the law is not enough”. The NHS is currently a “political football”, but the overriding objective must be one of patient safety. Whatever your views about managers following financial targets religiously, and regulatory authorities pursuing their own targets sometimes with equal passion, it is hard to escape from the desire for a national framework for patient safety. This is at a time indeed when it is proposed that the National Health and Patient Safety Agency should be abolished, which indeed has oversight of medical devices and equipment. Indeed, one of the findings of the Francis Inquiry is that essential medical equipment was not always available or working. A general problem with the approach of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) has been the abolition of ‘national’ elements, such as abolition of the Health Protection Authority. (more…)

Robert Francis has an incredibly difficult task. It is difficult for people who have not qualified, even managers and leaders of healthcare think tanks, to understand how this situation has arisen. Being a senior lawyer, his approach will necessarily involve “the law is not enough”. The NHS is currently a “political football”, but the overriding objective must be one of patient safety. Whatever your views about managers following financial targets religiously, and regulatory authorities pursuing their own targets sometimes with equal passion, it is hard to escape from the desire for a national framework for patient safety. This is at a time indeed when it is proposed that the National Health and Patient Safety Agency should be abolished, which indeed has oversight of medical devices and equipment. Indeed, one of the findings of the Francis Inquiry is that essential medical equipment was not always available or working. A general problem with the approach of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) has been the abolition of ‘national’ elements, such as abolition of the Health Protection Authority. (more…)

We've been here before. On legislation against toxic culture within the NHS: lessons from ENRON for the Francis Report.

Robert Francis has an incredibly difficult task. It is difficult for people who have not qualified in medicine, even managers and leaders of healthcare think tanks, to understand how this situation has arisen. Being a senior lawyer, his approach will necessarily involve “the law is not enough”. The NHS is currently a “political football”, but the overriding objective must be one of patient safety. Whatever your views about managers following financial targets religiously, and regulatory authorities pursuing their own targets sometimes with equal passion, it is hard to escape from the desire for a national framework for patient safety. This is at a time indeed when it is proposed that the National Health and Patient Safety Agency should be abolished, which indeed has oversight of medical devices and equipment. Indeed, one of the findings of the Francis Inquiry is that essential medical equipment was not always available or working. A general problem with the approach of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) has been the abolition of ‘national’ elements, such as abolition of the Health Protection Authority.

That the hospital assumes voluntarily a duty-of-care for its patient once the patient presents himself is a given in English law, but this fact is essential to establish that there has been a breach of duty-of-care legally later down the line. In the increasingly corporate nature of the NHS following the Health and Social Care Act, there is of course a mild irony that there is more than a stench of corporate scandals in the aftermath which is about to explode in English healthcare. Patients’ families feel that they have been failed, and this is a disgrace.

ENRON was a corporate scandal of equally monumental proportions, as explained here:

Mid Staffs NHS Foundation Trust was poor at identifying when things went wrong and managing risk. Some serious errors happened more than once and the trust had high levels of complaints compared with other trusts.

The starting point must be whether the current law is good enough. We have systems in place where complaints can be made against doctors, nurses, midwives and hospitals through the GMC, MWC and CQC respectively, further to local resolution. In fact, it is still noteworthy that many junior and senior doctors are not that cognisant of the local and national complaint mechanisms at all, and the mechanisms used for risk mitigation. There is a sense that the existing regulatory framework is failing patients, and public trust and confidence in medical and nursing, and this might be related to Prof Jarman’s suggestion of an imbalance between clinicians and managers in the NHS.

The Francis Inquiry heard a cornucopia of evidence about a diverse range of clinical patient safety issues, and indeed where early warnings were made but ignored. Prof Brian Jarman incredibly managed to encapsulate many of the single issues in a single tweet this morning:

Any list of failings makes grim reading. There are clear management failures. For example, assessing the priority of care for patients in accident and emergency (A&E) was routinely conducted by unqualified receptionists. There was often no experienced surgeon in the hospital after 9pm, with one recently qualified doctor responsible for covering all surgical patients and admitting up to 20 patients a night. A follower on my own Twitter thread who is in fact him/herself a junior, stated this morning to me that this problem had not gone away:

However, it is unclear what there may be about NHS culture where clinicians do not feel they are able to “whistle blow” about concerns. The “culture of fear” has been described previously, and was alive-and-well on my Twitter this morning:

Experience from other sectors and other jurisdictions is that the law clearly may not be protective towards employees who have genuine concerns which are in the “public interest”, and whose concerns are thereby suppressed in a “culture of bullying“. This breach of freedom of expression is indeed unlawful as a breach of human rights, and toxic leaders in other sectors are able to get away with this, in meeting their targets (in the case of ENRON increased profitability), “project a vision”, and exhibit “actions that “intimidate, demoralize (sic), demean and marginalize (sic)” others. Typically, employees are characterised as being of a vulnerable nature, and you can see how the NHS would be a great place for a toxic culture to thrive, as junior doctors and nurses are concerned about their appraisals and assessments for personal career success. “Projecting a vision” for a toxic hospital manager might mean performing well on efficiency targets, which of course might be the mandate of the government at the time, even if patient safety goes down the pan. Managers simply move onto a different job, and often do not have to deal even with the reputational damage of their decisions. Efficiency savings of course might be secured by “job cuts” (another follower):

Another issue which is clearly that such few patients were given the drug warfarin to help prevent blood clots despite deep vein thrombosis being a major cause of death in patients following surgery. This is a fault in decision-making of doctors and nurses, as the early and late complications of any surgery are pass/fail topics of final professional exams. Another professional failing in regulation of the nurses is that nurses lacked training, including in some cases how to read cardiac monitors, which were sometimes turned off, or how to use intravenous pumps. This meant patients did not always get the correct medication. The extent to which managers ignored this issue is suggestive of wilful blindness. A collusion in failure between management and surgical teams is the finding that delays in operations were commonplace, especially for trauma patients at weekends; surgery might be delayed for four days in a row during which time patients would receive “nil by mouth” for most of the day.

Whether this toxic culture was isolated and unique to Mid Staffs, akin to how corporate failures were rather specialist in ENRON, is a question of importance. What is clear that there has been a fundamental mismatch between the status and perception of healthcare entities where certain individuals have “gamed” the situation. Alarmingly it has also been reported that the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust have also had a spate of failures in in maternity, A&E and general medical services. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002) was enacted in the US in response to a number of high-profile accounting scandals. In English law, the Financial Markets and Services Act (2010), even during Labour’s “failure of regulation” was drafted to fill a void in financial regulation. There is now a clear drive for someone to take control, in a manner of crisis leadership in response to natural disasters. Any lack of leadership, including an ability to diagnose the crisis at hand and respond in a timely and appropriate fashion, against the backdrop of a £2bn reorganisation of the NHS, are likely to constitute “barriers-to-improvement” in the NHS.

This issue is far too important for the NHS to become a case for privatisation. It is a test of the mettle of politicians to be able to cope with this. They may have to legislate on this issue, but David Cameron has shown that he is resistant to legislate even after equally lengthy reports (such as the Leveson Inquiry). It is likely that a National Patient Safety Act which puts on a statutory footing a statutory duty for all patients treated in the NHS, even if they are seen by private contractors using the NHS logo, may be entitled to a formal statutory footing. The footing could be to avoid “failure” where “failure” is avoiding harm (non-maleficence). Company lawyers will note the irony of this being analogous to s.172 Companies Act (2006) obliging company directors to promote the “success” of a company, where “success” is defined in a limited way in improving shareholder dividend and profitability under existing common law.

The law needs to restore public trust and confidence in the nursing and healthcare professions, and the management upon which they depend. The problem is that the GMC and other regulatory bodies have limited sanctions, and the law has a limited repertoir including clinical negligence and corporate manslaughter with limited scope. At the end of the day, however, this is not a question about politics or the legal and medical professions, it is very much about real people.

The advantage of putting this on the statute books once-and-for-all is that it would send out a powerful signal that actions of clinical and management that meet targets but fail in patient safety have imposable sanctions. After America’s most high-profile corporate fraud trial, Mr Lay, the ENRON former chief executive was found guilty on 25 May on all six fraud and conspiracy charges that he faced. Many relatives and patients feel that what happened at Stafford was much worse as it affected real people rather than £££. However, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act made auditors culpable, and the actions of managers are no less important.

This is not actually about Jeremy Hunt. Warning: this is about to get very messy. That Mid Staffs is not isolated strongly suggests that an ability of managers and leaders in Trusts to game the system while failing significantly in patient safety, and the national policy which produced this merits attention, meaning also that urgent legislation is necessary to stem these foci of toxicity. A possible conclusion, but presumption of innocence is vital in English law, from Robert Francis, and he is indeed an eminent QC in regulatory law, is that certain managers were complicit in clinical negligence at their Trusts to improve managerial ratings, having rock bottom regard for actual clinical safety. This represents a form of wilful blindness (and Francis as an eminent regulatory QC may make that crucial link), and there is an element of denial and lack of insight by the clinical regulatory authorities in dealing with this issue, if at all, promptly to secure trust from relatives in the medical profession. The legal profession has a chance now to remedy that, but only if the legislature enable this. But this will be difficult.