Home » Posts tagged 'patient safety'

Tag Archives: patient safety

The perfect storm around #BawaGarba was a long time coming

As a result of my erasure in 2006 from the register of medical professionals in the UK, I had a lot of time to reflect on the events leading up to it. I have from time to time also reflected on this following my restoration in 2014. In the meantime, I had re-trained in law, paradoxically inspired by my experience of the judicial process. This was not a brief Masters in medical law, but both my Bachelor and Masters of Law, as well as the pre-solicitor training course. To do the last bit, I had to be approved as a fit and proper person by the legal regulator, the Solicitors Regulation Authority. I enjoyed my study of the English legal system, and reflect that if I had never studied law I would never have met the late Prof Gary Slapper – a formidable academic with an interest in conspiracy theories and corporate manslaughter.

This is all rather awkward, not least because Charlie Massey and Jeremy Hunt get on well, despite having divergent views on the implications of the #BawaGarba judgment. In a way, the General Medical Council (GMC) does not actually do ‘personal’, although ensuing events do rather appear like a hate campaign. It has become traditional to issue a sop to the ‘victim’ of misfeasance of a Doctor, and I do genuinely feel that there can be few things worse than the mental anguish of a grieving relative. The GMC and Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service maintain separation of powers, and, whilst I feel that the GMC can move in mysterious ways, I feel that the GMC believe that they are doing their very best to maintain public safety and confidence in the medical profession. This blogpost is therefore not an easy one to write, and inevitably will mean that I could accidentally cause offence. I am reflecting on issues to the best of my ability, and, if I fall short, I do apologise.

#BawaGarba found herself in a perfect storm. There are various systemic factors arguably out of direct control of the GMC. These are the exact funding of the NHS, including whether there is a sufficient number of doctors on rotas in individual hospitals. Notwithstanding, the GMC has a statutory duty in education and training, and, from what I know, will intervene in cases where NHS Trusts offer a suboptimal training experience. But there are important other systemic factors. It is quite common for non-white British trainees, once a GMC alert has been triggered, to be ‘thrown to the wolves’ from the regulatory process, but whether this achieves statistical significance is worth exploring. The trend has been for, once these Doctors have been reported, for all positive references to be withdrawn, and, often, although the source of the leaks are never identified, for the Doctors to receive a barrage of unfavourable press prior to any hearing. A media presence seems to defy any traditional notion of contempt of court, or right to a fair trial, as Doctors are subject to a total monstering and humiliation in the media. But it is not uncommon for papers in the English media, and their class of readers, also to subject groups of Doctors, such as EU Doctors, to an utter monstering as well, allowing xenophobia and outright racism to flourish. The scope for moral panic is enormous. But to lay these problems at the foot of the GMC, I feel personally, is unfair.

The GMC indeed also has an important statutory duty for patient safety under section 1 of the Medical Act 1983. The “There but the grace of God go I” used alarmingly frequently by white, English doctors on Twitter might reflect the observation that some Doctors are safer from attacks from institutional racism than others. This is particularly problematic if the NHS Trusts continue on its trend to trigger an official regulatory complaint effectively to cover their own backs rather than a genuine attempt to improve the performance, health and wellbeing of their Doctors employed under employment contracts. This has indeed been witnessed in the enforcement of the junior doctors’ contracts, arguably. Also, the “There but” observation is also problematic from the point of view that it seems to signal an admission that registers an admission that registered Doctors go to work knowingly taking risks and making mistakes. Most Doctors will admit to having taken risks and having made a mistake, and the number of mistakes reported daily in the NHS, a mere fraction of the real number, must urge a need for an open and transparent culture where people can learn from mistakes. But the GMC and the higher courts will tend not to tolerate any mistakes, or catalogues of error, whatever the mitigating factors. This might include an unblemished record for 30 years. The issue is that if the performance is way below a standard, there can be no excuse for it. If somebody has died, the threshold for mitigation has to be high, most reasonable persons might argue. And if a court of law has found someone guilty of manslaughter, whatever the process involved for doing so or the people involved, it is hard to leave no sanction on the Doctor, it is argued, whatever the need for organisational learning. Both the GMC and higher courts have consistently argued that public trust and confidence in the medical profession are more important than any individual doctor’s career.

The argument that ‘We go to work and are caught between a rock and a hard place’ merits scrutiny too. This comes down to the nature of how a crime is satisfied in English law – there can be intention to do the crime, and, although there is some finesse about the jurisprudence, there might be recklessness. The law in this is fairly well settled since R v Adomako. It might seem unfair to blame a Doctor having to cover seven bleeps one morning, but the point in law is that the Doctor by carrying those bleeps has assumed a duty of care to his or her patients, and any breach therefore of this duty of care, given the issues of causation and remoteness, is negligence. It might be argued that in tort the Doctor has assumed this responsibility under duress, but in reality most Doctors pick up the bleep from an office in the Hospital without any altercation. And Doctors are entitled to resign if they feel that there has been a fundamental breach of a contract, including a bilateral feeling of trust and confidence, between employer and employee. In reality, Doctors never do, despite the potential risks for patient safety.

Whilst there might be outrage about the lack of due emphasis on organisational learning, this organisational learning nor indeed any individual duty of candour are operational at any meaningful statutory level, meaning they exist in an Act of parliament or statutory instruments. And nobody is above the law. If there had been no sanction on #GawaBarba, a possible interpretation might have been that mistakes, whatever the reason, are excusable because of the ‘state of the NHS’. It might then be argued that the correct course of action might be for corporate manslaughter against the Secretary of State for health and social care, for ‘avoidable deaths’, but this has to be proven beyond reasonable doubt – an incredibly difficult offence to fulfil, as the late Prof Gary Slapper I am certain would testify.

I doubt, if #BawaGarba finds herself back on the GMC Register, she will find it easy to find employment again, especially with at least a five year gap in training. The GMC, even with its statutory duty for education and training, as well as patient safety, seems pretty indifferent to the professional rehabilitation and retraining of Doctors put back onto their Register. But the observation that no Doctor can ever be professional rehabilitated does concern me, even with the strong emotions that the ‘punishment should fit the crime’, and the need for a scalp can be overwhelming. For example, #BawaGarba has found that her subsequent good performance had become somewhat irrelevant as far as the regulator and higher courts were concerned.

As the old trope provides, there are no winners. There are only losers. It’s said that the GMC ‘doesn’t do personal’ in the same way a sanction is delivered in the same way a parking ticket is issued, and the GMC’s purpose isn’t, it is argued, to do ‘show trials’. The GMC’s position is that they are not in the business of ‘punishing Doctors’, but, I feel, it is of concern that unintended consequences, including a culture of fear, could continue to be dominant in the medical profession. The GMC doesn’t likewise, perhaps reflecting their perceived concerns from the general public, want to allow free rein on Doctors ‘free to make mistakes’, and good doctors will argue that they are all trying to do the job to ‘the best of their abiility’. The problem facing the GMC is whether ‘the best of someone’s ability’ is simply good enough. The general approach is that there is no shortage of doctors, and it is a honour to be a registered doctor. Whether there is a sufficient number of doctors for the demand is a concern the GMC can decide to involve itself with, or not. There is a clause in the code of conduct – Good Medical Practice, 2013 – stating that it is the responsibility of doctors to identify any shortfall of resources. I doubt all the senior Consultants or even STs in training taking to Twitter outraged about the #BawaGarba judgment are writing this morning to the GMC to warn about shortage of resources in their own hospitals, despite concerns about patient safety. It is noteworthy that the GMC in their statement on the case mentioned this only yesterday even. But individual Doctors have also been rather effective at protecting their own backs?

Golden handcuffs

“Golden handcuffs” in corporate land are normally financial incentives to stop employees from leaving.

My friend described to me yesterday a different type of “golden handcuffs” at play in his NHS Foundation Trust. I spent an hour with him, a youngish NHS Consultant in England. He works as a general physician. He also has direct links to the RCP, of which he is a senior member. As you would expect, he was knowledgeable about what is happening to the National Health Service, which he adores. But he feels that the system in his Trust has gone very badly wrong. Whilst autonomy and independence of NHS Foundation Trusts are both key features of the policy, he feels it likely that similar behaviours are being emulated in other Trusts. He feels there to be a rife ‘target culture’, led by non-clinicians. This, he attributes, occurred when the new management took over in the Trust, rather than when there was any change in central party politics.

He feels essentially that he and colleagues in the NHS are being ‘bought with silence’. He feels, rather perversely, that awards which promote, say, excellence, leadership or innovation are in fact having an unwanted effect. People, he says, with numerous awards, even if they have strong misgivings about the system, are far less likely to raise concerns. Raising concerns makes it more difficult to get an award; and awards impact on your assessment for clinical excellence awards. The Trust he works in is described as having ‘clinical leaders’ who are essentially ‘yes men’ or ‘wing men’, who “protect” higher management. He’s adamant that management have become really focused on one thing: their own reputation management. However, he does want his tale to be heard, as he feels that there are lessons to be learnt about how clinicians interact with management in the English NHS. He feels that the English NHS has become a joke in the way the system is basically rigged towards not identifying good practice, and not sharing any issues with patients.

The background to this is as follows. To be honest, the coverage of the problems in the NHS had washed over me when it veeered towards a complicated statistical debate. I watched the news coverage like many of us did. We all got a bit sidetracked with the thousands of excess or needless deaths allegations. We wondered about its statistical validity. We wondered about the truth of some of more hyperbolic claims in the media. Some people that it was all a ruse to picture the NHS in a permanent state of turmoil and disaster, interspersed with some quality gems about how fantastic the NHS is. He feels that the NHS as a public service could be superb, but has concerns that the public-run NHS has allowed itself ‘to get into this mess’.

When I mentioned his remarks to someone, that person even said, “Is this guy for real? It’s too good an account. Isn’t it fiction?”

What he described truly shocked me. I’m an avid supporter of the NHS, but what he described was very clearly a system in his Trust which had gone very badly wrong. Even worse, it was extremely unlikely that patients would know about poor quality care because of the resistance of clinical staff and managers to tell the patients. His Foundation Trust is one of the best performing hospital units in England, with one of the best figures for the 4 hour wait. The management is indeed very keen to trumpet loudly this figure. And yet the way the acute medical takes are being run are utterly shambolic, according to him.

He feels that it’s become impossible to monitor the quality of his team’s clinical decision making. There’s no way of ascertaining whether patients were given the best available management steps, as the service is totally uninterested in discussing cases openly. The management prefer to rely on targets instead, and increasingly they’ve stopped measuring certain targets (such as length of stay). A poor length of stay figure in his Trust will invariably be spun as problems in discharging a patient to the community, rather than the notion that the patient was not properly given the correct management in hospital. A mention of ‘C difficile’ on the death certificate would trigger a root cause analysis, however. Because of staffing issues, he only has a skimpy foundation years team, and one Staff Grade; he has no Registrar. Apart from things blatantly going wrong, generating a complaint, there’s no way of telling whether other Doctors are exercising poor judgment in clinical decision-making.

But he does “blame” various people. He blames his management for refusing to acknowledge any bad news, let alone offering any solutions. He doesn’t blame the majority of nurses whom he perceives as being worn out and demoralised by the conditions they’re working in. But he does blame the senior nurses who are trying to spread the idea that everything’s great, for not risking their bonus. And most of all he blames other Consultants for mostly keeping silent about the poor medical management of the patients. He says he presents his findings at the Grand Round, and senior consultants often come up to him to thank him for being problems. But in the same breath he says nothing of ‘them’ report the same problems. He says of all the people it’s the junior medics who are likely to raise complaints. That’s because they don’t get any experience in medicine of clerking and managing a patient, so it’s in their interests to express their training concerns. And bear in mind this a “University teaching hospital” too. My Consultant friend was even able to raise an audit of these concerns at the tail end of a meeting with the Deanery and management staff. The management staff had no idea that they were about to be ambushed, and had presented an unblemished account. But the manoeuvre worked, as the Deanery is now receiving detailed feedback from my Consultant friend. And, particularly, the junior doctors didn’t mind raising these concerns as they are mostly looking forward to leaving the Trust, as it’s felt that they’re there on a ‘merry go round’ basis.

He says the culture is insufferable. “You keep your head down. You merely survive.”

He writes e-mails to his senior clinicians, but he never receives replies. People who raise concerns are first ignored, then discredited, then attacked, and starved of any mechanism for career progression. He says the management is ‘totally uninterested’ in his views on clinical quality control. He describes a ‘really horrible’ culture of exclusion if you voice any concerns. He says nothing can disrupt the script between the clinical leadership and the management, of how to paint the performance of the Trust in public.

He says the whole Emergency Room is set up wrong, as it has too few beds, and there’s no choice but to shunt patients to any ward within four hours. He explains a team of mainly Emergency Room (ER) doctors see the patient. Towards the end of the four hour window, a Specialist Registrar will do a minimalistic thirty minute clerking, only to be followed by a brief assessment by ER Consultant as a ‘sign off’. When the patient is received by him on a medical ward, often the basic admission investigations like bloods and chest x-ray haven’t even been done. He says he often deletes inappropriate medications off drug charts, and orders outstanding investigations. But he feels exasperated at firefighting.

He feels the complaints procedure in his Trust is virtually non-existent. Whilst patients receive a ‘welcome pack’ from the nursing staff about how to make a complaint, the staff actively do not explain to patients how they can complain about this care. This I think is a complete anethema compared to the solicitors’ regulatory code where solicitors should explain the complaints procedure on their first meeting. He says complaints are never actioned upon anyway. There’s no critical feedback loop from primary care to hospital care, or vice versa. He finally adds that the Friends and Families Test is not going anywhere in his Trust, as patients aren’t told when they receive bad care at all. If anything this test is being used by management to promote how excellent the Trust is, as management benefits from such positive reporting.

He says he’s had incomprehensible messages appearing to come from management how his discharge letters should use preferred terms such as “urosepsis” to “UTI”, or “NSTEMI” to “acute coronary syndrome”; and nobody can work out why apart from how his FT gets paid. As to what to do next, he freely admits having drawn blanks with his own NHS FT’s management and clinical ‘leaders’. He’s reported it so far to the Medical Protection Society, so I suppose he’s waiting to hear what happens. He feels that the BMA are utterly irrelevant to his concerns. He knows that the mandate for an external review from the Royal College of Physicians can only come from management. And unsurprisingly they haven’t asked for an external review. So he intends to by-pass management, being completely at the end of his tether, by asking the College directly. This reckons is a fatal flaw in the system, but one which is easily remediable.

I asked him why he hadn’t gone to the press. I thought he’d come up with the usual Doctor-patient relationship, but surprisingly he explained he hadn’t deliberately just in case it would give the Trust’s management to ‘cover their tracks’. He did look genuinely upset at this thought. He’s been invited to become an Inspector for the Care Quality Commission. He feels this is the only way now to voice his concerns.

But most of all he blames other Consultants for Mid Staffs. He feels it was up to the Consultants ‘to say something about it‘. Those who did were victimised. Those who didn’t survived. He says he can’t put up with the situation any longer because patient safety is being compromised simply so the management can ‘look good’. He feels quite paradoxically that ‘competition’ has resulted in this mess: competition amongst health professionals not to whistleblow, and competition amongst hospital managers who don’t give a toss for patient quality of care as long their national rankings for key metrics are good.

And he feels that his personal situation is not unrepresentative. This, above all, is the thing that I find the most scary.

Fears and smears – wilful inattention from healthcare journalists?

In an article today in the Independent, subtitled “Fears and smears”, Ed Miliband MP writes:

“They want to distract attention from the issues that matter. With the support of a determined section of the press, they have decided that mudslinging matters more than the futures of millions of families across this country.”

Discussion of the NHS is an incredibly sensitive area and yet it has been done incredibly badly by many journalists and politicians.

Mid Staffs was an unacceptable disaster. It was THE low point in the NHS.

Relatives of loved ones have shown incredible bravery and resilience in the face of an unbelievably tragic intolerable event.

For many, the issues in Mid Staffs appeared to be simply brushed under the carpet for political purposes, and real patients and relatives suffered.

The claim over professional codes and a duty of candour

On Thursday, Jeremy Hunt gave an answer on Mid Staffs on the BBC programme ‘Question Time‘. Regarding making it easier for people to speak out, “people are going to be given protection in their professional codes which have happened before.”

Mr Hunt is therefore speaking as if this has sprung up from nowhere.

Not true, even from the briefest scan of ‘Five Minute Digest – Duty of Candour’ in ‘Pulse Today‘:

The claim that Burnham opposed an inquiry

There are two inquiries – when you read the rest of this article, be mindful that

- November 2009 – Robert Francis QC begins hearing evidence in private as part of his independent inquiry

- February 2010 – Robert Francis QC publishes his independent inquiry report into the poor care at Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust

- May 2010 – Change of government and Health Secretary

- November 2010 – The public inquiry begins to hear evidence

- December 2011 – The public inquiry finishes hearing evidence after more than 12 months

In Question Time last week, regarding Mid Staffs, Mr Hunt explained, “Your party opposed a public inquiry. Andy Burnham decided to oppose a public inquiry.”

The Executive Summary of the Report of the public inquiry, published in 2013, is here.

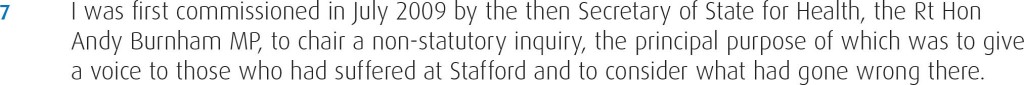

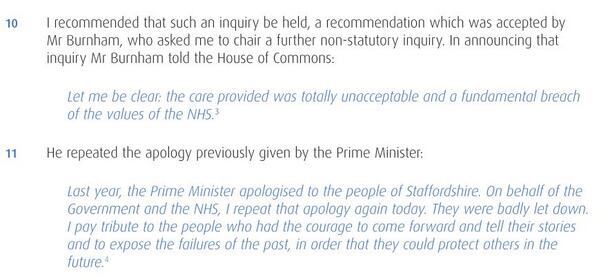

The way the original private inquiry was set up by Andy Burnham MP, the then Secretary of State for Health, is described in the 2013 Francis report as follows.

A new Government was elected in the UK in May 2010. The way in which Andrew Lansley MP, the then Secretary of State for Health, set up a public inquiry is provided in the 2013 Francis report as follows.

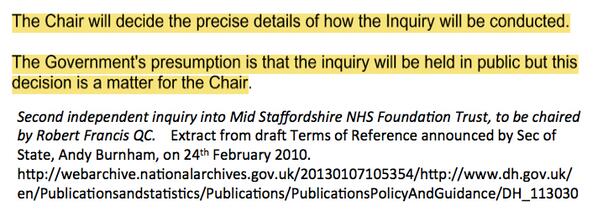

This actually came as no surprise, as Andy Burnham MP had already stated that the second Inquiry would be held in public, as cited here.

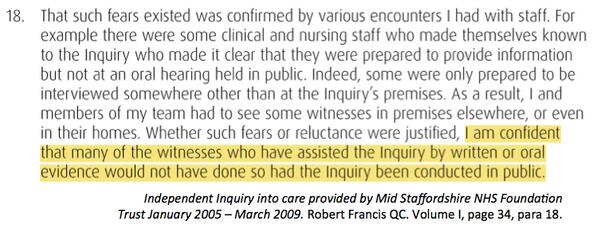

Francis himself did not want the first inquiry to sit in public for the first time, and is even reported as being satisfied with the arrangements, as cited here.

The problem here is in the media at large the genuine message that Burnham set up the first inquiry in 2009 ‘to give patients a voice’ has been swamped by the toxic meme from some, and they know who they are, that ‘Burnham blocked an inquiry’.

The claim that Burnham never apologised

Another blatant classic lie is that Burnham has never ‘apologised for Mid Staffs’.

This is addressed too, as cited here.

The claim that Burnham resisted an inquiry under the Inquiries Act

Burnham obviously did not have any powers as Secretary of State for Health after the General Election of May 2010. The decision for the second public inquiry comes after that date.

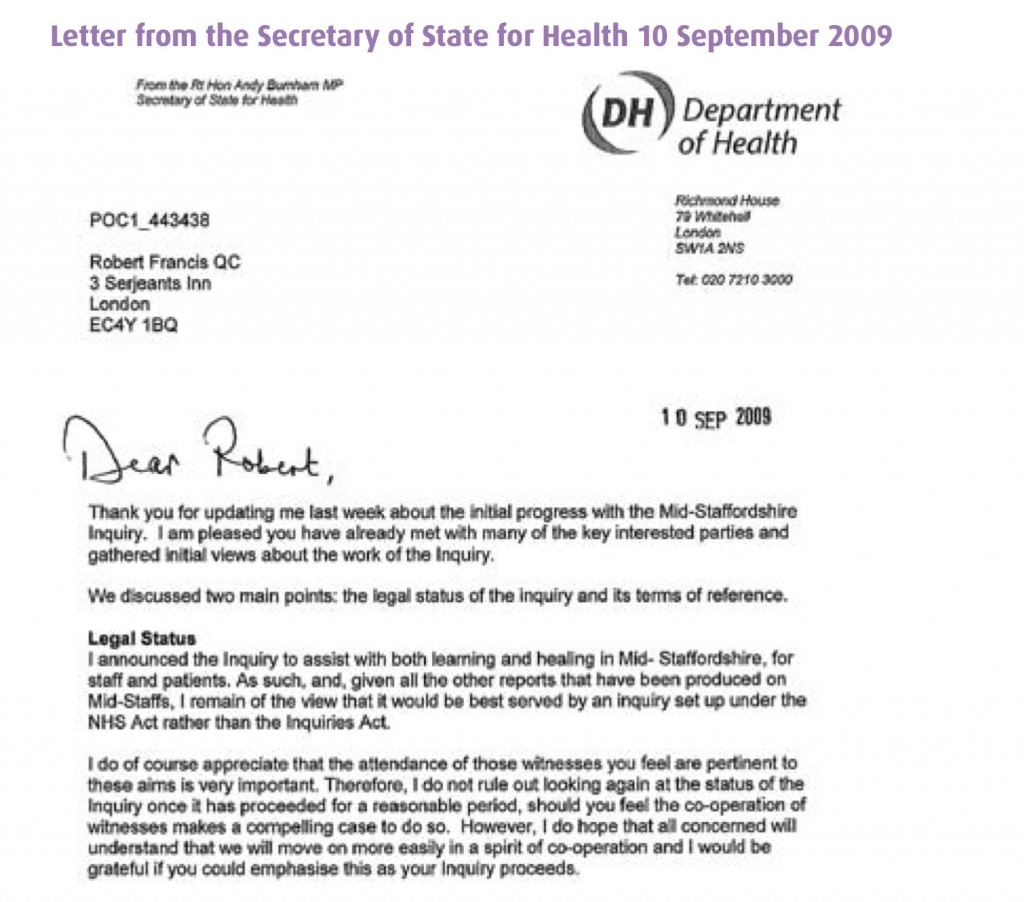

It has been claimed furthermore that Andy Burnham MP resisted his inquiry to take place under the auspices of the Inquiries Act, but Burnham did actually leave it all times to be directed by Francis, the Chair of the Inquiry.

This legally is a somewhat obtuse claim, as it was a Labour government which enacted the Inquiries Act in 2005 in the first place.

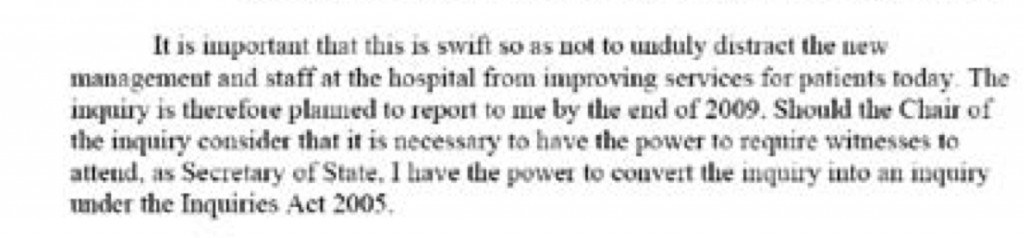

In Appendix 1 of the bundle of documents entitled “Independent Inquiry into care provided by Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust January 2005-March 2009 Volume 1″ Appendix 2, Andy Burnham MP as the then Secretary of State for Health in his Written Ministerial statement (21 July 2009) first cites his perceived need to set up an inquiry “swift so as not to unduly distract the new management and staff at the hospital from improving services for today”, but that he has the power to convert the Inquiry to one under the Inquiries Act should the Chair of the Inquiry (Robert Francis QC) should demand it.

This exact text of the statement is indeed evidenced in Hansard, for 21 July 2009 Column WS188 as per here.

In Appendix 2 of the bundle of documents entitled “Independent Inquiry into care provided by Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust January 2005-March 2009 Volume 1″ Appendix 2, Andy Burnham MP as the then Secretary of State for Health repeats (10 September 2009) his willingness for his inquiry to be set up under the Inquiries Act not the NHS Act.

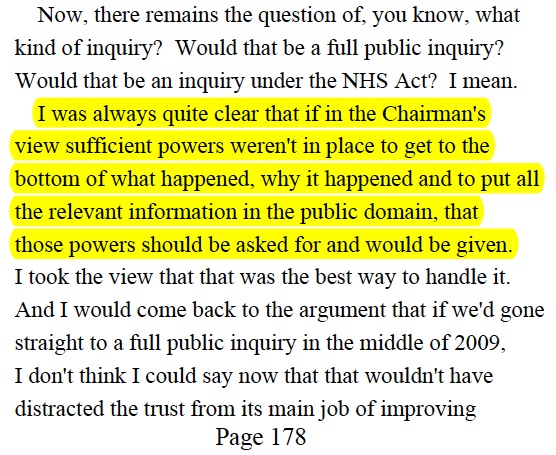

This is the evidence that Burnham gave to Francis 2 on 6 Sep 2011, page 178:

Indeed, parsimoniously, the option of ‘converting another form of inquiry’ into an Inquiry as under the Inquiries Act at any time is clearly good application of the law, under section 15 Inquiries Act (2005).

The claim that ‘wilful neglect’ legislation is a fundamental new shift in the law

The Berwick Report itself was all about constructive organisational learning, and only introducing a statutory crime of ‘wilful neglect’ for the most extreme cases.

Some vocal campaigners in Mid Staffs clearly desire targeted retributive justice, but the media thus far have refused to cover why the law of ‘wilful neglect’ in the form of section 44 Mental Capacity Act (2005) has failed to see a flurry of successful criminal prosecutions in Mid Staffs. We have instead discusssed it here. ‘Wilful neglect’ is NOT a fundamental new shift in the law, unless it can now be applied to adults with full capacity.

The claim that ‘there was a culture of cruelty in the NHS and no-one noticed”

Staff in various NHS Trusts have voiced loudly their resentment as being targeted in some sort of ‘hate campaign’.

Jeremy Hunt last week specifically referred to how a culture of cruelty ‘became normal in our NHS’, not in any particular Trust.

as cited in Hansard 19 November 2013.

Summary

The problem in this imbalance of irresponsible reporting is that it creates a culture of fear in NHS nurses, even in those ‘who have nothing to hide’. It is not a mature discussion of the technical problems in the law. It is instead ‘red meat’, ‘dog whistle’ politics of the worst kind, of a particular political inclination. As a result of memes about the Inquiry, candour and putting clinical staff in the clink, an irresponsible media has diverted attention from important issues.

By allowing copious air time for lies, the important discussion of why A&E is experiencing difficulties, a lack of a stated minimum level of safe staffing, why social care cuts have been so dangerous, or why NHS 111 has failed so dramatically, have not been explored in any level of acceptable detail.

Sadiq Khan MP tried valiantly to bring up how staffing levels had been so low, and ‘without the doctors and nurses, it’s all talk and no action.” But the stench of the narrative above diverted him from discussing the critical issues as much as he would have liked, although he did get in an official statistic about a cut in nursing numbers.

Real staff are none-the-wiser. Patient campaigners are led down the river without a paddle. Voters are completely bamboozled.

This is an unholy disgusting mess from those responsible. Call it wilful inattention.

Thanks to the public tweets of @gabrielscally for many of the extracts cited in the article.

Does speaking out safely under the Public Interest Disclosure Act (1998) work?

The irony is that, if as a junior doctor you spend an extra three hours unpaid checking that all the results for your unwell patients are in, nobody will thank you, but if any mistake is made the system can come down on you like a tonne of bricks. This aggressive blame culture is at odds with the much-needed openness many love talking about but actually fail to practise. How clinical staff, and indeed managers, are able to speak out safely about problems in the system, such as inadequate levels of staffing for the clinical workload, has never been a more important issue as the NHS seeks to make £20bn efficiency savings in the next few years.

The employer in English law is supposed to have a duty of trust and confidence in the employee, and this is supposed to be mutual. This is often called “the duty of fidelity”. There is therefore a problem if any part of the English law is perceived to come down noticeably in favour of one political party. The number of examples of ‘successful whistle blowers’ is relatively small. Whilst thought leaders in business management have advocated that whistleblowers should be visibly promoted in an organisation to bring about a cultural change, nothing in reality could possibly be further from the truth in the current English NHS.

To be a ‘whistle blower‘, you have to be very brave. The accounts here in this Channel 4 report are truly horrific.

The stories of the culture of fear are remarkably similar.

Management styles in a particular Trust were described as ‘coercive, vindictive, and bullying’. The Care Quality Commission have now prioritised learning from whistle blowers, symbolising a dramatic change in direction. As this video above explains, the temporary result has superb NHS clinicians have left to practise abroad.

The life cycle of the whistle blower is indeed fascinating. Here’s the a very recent description of it from Patients First, which makes for most interesting reading (thanks to the author Roger Kline – @rogerkline – for sharing; it formed evidence to the ‘Whistle-blowing Commission).

The NHS is not unique, and an initial problem may indeed arise from a law which is designed to cover a number of different sectors. Health and safety disasters (for example, the sinking of the Herald of Free Enterprise, the Lyme Bay drownings and the Piper Alpha explosion), financial scandals (for example, at Maxwell pensions, Doncaster Council, Barlow Clowes, Barings Bank and BCCI) and the work of the Committee on Standards in Public Life, all emphasised the need to provide greater protection for whistle blowers in the UK.

Whistle blowing is ‘the disclosure by organization members (former or current) of illegal, immoral or illegitimate practices under the control of their employers, to persons or organisations that may be able to affect action’ (Near and Miceli, 1985). ‘Blowing the whistle’ was, in fact, a relatively unknown expression in the English jurisdiction when the Public Interest Disclosure Act (Pida) became law in 1998, providing workers with overdue protection against dismissal or victimisation for raising concerns about illegal or unsafe practices. But since compensation is uncapped, employees are sometimes tempted to use the law tactically to get around the £70,000 to £80,000 limit on unfair dismissal compensation.

The ‘patient safety’ issue in the NHS in England

In the English NHS, one of the major findings of the Francis inquiry into care failings at Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust was that staff who raised concerns about patient care were not taken seriously. It is commonplace to hear that even if a large volume of complaints many of them are not actioned. Some complainants are said even to be bullied and threatened, and receive no protection from their employer. Sadly, it is now impossible to claim that the situation at Mid Staffs is far from unique – many staff working for the NHS and other healthcare providers have raised concerns within their organisations and have suffered personally and/or professionally. They have been bullied by colleagues, discredited by their employers or even lost their jobs. This is not a problem which solely rests in the public sector either, as the events in Winterbourne for example have demonstrated.

The “Nursing Times Speak Out Safely (SOS)“ (@NursingTimesSOS) campaign aims to help ensure that healthcare providers listen to, support and value staff who raise concerns about the quality of care, and learn from the issues they raise. One of its aims is to encourage NHS organisations and independent healthcare providers to develop cultures that are honest and transparent, to actively encourage staff to raise the alarm when they see poor practice, and to protect them when they do so. So far, the uptake has been good, and one cannot imagine intuitively why NHS England Trusts should not wish to be involved in such an important campaign.

Personal sacrifices

The issue of personal detriment to whistle blowers, however, is a tragic one. Rothschild and Miethe (1999) found that over half the whistle blowers they interviewed had family problems. They found that two-thirds of whistle blowers ‘‘lost their job or were forced to retire’’ and ‘‘were blacklisted from getting another job in their field.’’ Consequently, two-thirds of them also had severe financial problems. They also found that 84% suffered from ‘‘severe depression or anxiety’’ and over two-thirds of them also had ‘‘declining physical health.’’ That Gunsalus (1998) wrote an article entitled ‘‘How to blow the whistle and still have a career afterwards’’ is in itself sad.

A whistle blower mentioned by Oliver (2003) ‘‘estimates that his legal costs have exceeded $130,000.’’ Alford (2007) sees suffering as an essential part of whistle blowing: ‘‘the whistle blower is defined by the retaliation he or she receives. No retaliation, and the whistle blower is just a respon sible employee doing her job to protect the company’s interest.’’ If ‘‘often the protest is most effective if one has already resigned from the organization’’ (Harris et al., 2005) then one can only choose between a total self-sacrifice and a partial and pointless self-sacrifice. A further problem is that it is clear that the NHS has been putting aside a considerable amount of money regarding ‘gagging clauses’, even if the Department of Health had considerable problems in being open and transparent about their existence for some time.

A former boss of a hospital which was being investigated over high death rates told senior MPs in the prestigious Commons Select Committee there was a culture of “sheer bullying” in the NHS. The brace Gary Walker, former United Lincolnshire Hospitals Trust CEO, said he was sacked because of a row over an 18-week non-emergency waiting list target. He said he was threatened by the East Midlands Strategic Health Authority when he flagged up capacity problems. Mr Walker was officially dismissed in 2010 for “gross professional misconduct”. The NHS stated he was sacked for allegedly swearing in a meeting and denied Mr Walker’s claims he was “gagged” by a compromise agreement for raising concerns about patient safety.

A study commissioned by PCAW from Cardiff University covering the period January 1997 to December 2009 found that 54% of the national newspaper stories represented whistle blowers in a positive light, while only 5% of stories were negative. The remainder (41%) were neutral.The most commonly reported form of wrongdoing was financial malpractice, which was the subject of 27% of the newspaper articles. One in five cases (20%) of media coverage of whistle blowing dealt with concerns about public safety and 63% of it related to the public sector.

Problems with the common law

There were problems in the common law which were known to legislators before they dealt with drafting their new Statute.

The common law has never given workers a general right to disclose information about their employment. Even the revelation of non- confidential material could be regarded as undermining the implied duty of trust and give rise to an action for breach of contract. In relation to confidential information obtained in the course of employment, the common law again provides protection against disclosure through both express and implied terms.

The duty of fidelity can be used to prevent disclosures while the employment subsists, and restrictive cove- nants can be used to inhibit the activities of former employees after the relationship has ceased. However, post-employment covenants will only be enforceable if they can be shown to protect legitimate business interests and are reasonable in all the circumstances.

Even in the absence of an enforceable post-employment “restrictive covenant”, ex-employees are bound not to reveal matters learned in confidence during their employment. Where employees have allegedly disclosed confidential information in breach of an express or implied term, they may seek to invoke a public interest defence to a legal action. Although the common law allows the public interest to be used as a shield against an injunction or damages, it has proved to be a weapon of uncertain strength.

Statute law: the Public Interest Disclosure Act (1998)

The Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 (c.23) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that protects whistleblowers from detrimental treatment by their employer.

Influenced by various financial scandals and accidents, along with the report of the Committee on Standards in Public Life, the bill was introduced to Parliament by Richard Shepherd and given government support, on the condition that it become an amendment to the Employment Rights Act 1996. After receiving the Royal Assent on 2 July 1998, the Act came into force on 2 July 1999.

It protects employees who make disclosures of certain types of information, including evidence of illegal activity or damage to the environment, from retribution from their employers, such as dismissal or being passed over for promotion. In cases where such retribution takes place the employee may bring a case before an employment tribunal, which can award compensation.

Section 1 of the Act inserts sections 43A to L into the Employment Rights Act 1996, titled “Protected Disclosures”. It provides that a disclosure which the whistle blower makes to their employer, a “prescribed person“, in the course of seeking legal advice,

In addition, the disclosure must be one which the whistle blower “reasonably believes” shows a criminal offence, a failure to comply with legal obligations, a miscarriage of justice, danger to the health and safety of employees, damage to the environment, or the hiding of information which would show any of the above actions. These disclosures do not have to be of confidential information, and this section does not abolish the public interest defence; in addition, it can be the disclosure of information about actions which have already occurred, are occurring, or could occur in the future.

The list of “prescribed persons” is found in the Public Interest Disclosure (Prescribed Persons) Order 1999, and includes only official bodies; the Health and Safety Executive, the Data Protection Registrar, the Certification Officer, the Environment Agency and the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry. An employee will be protected if he “makes a disclosure in good faith” to one of these people, and “reasonably believes that the relevant failure…is a matter in respect of which the person is prescribed and the information is substantially true”.

If an employee does make such a disclosure, Section 2 inserts a new Section 47B, providing that the employee shall suffer no detriment in their employment as a result. This includes both negative actions and the absence of action, and as such covers discipline, dismissal, or failing to gain a pay rise or access to facilities which would otherwise have been provided.

If an employee does suffer a detriment, he is permitted to make a complaint before an employment tribunal under Section 3. In front of an employment tribunal, the law is amended in Sections 4 and 5 to provide compensation, and to reverse the burden of proof; if an employee has been dismissed for making a protected disclosure, this dismissal is automatically considered unfair.

Moving forward

Unfortunately, it appears that PIDA 1998 may be too pro-employer. Given the imbalance in resources and expertise in defending legal claims from the NHS compared to claimants, this is clearly a potential problem. It is too easy for the NHS to be accused of operating “bully boy” tactics, when there are petrified whistleblowers who find themselves totally disenfranchised in the system.

Sadly it appears that PIDA 1998 has not adequately protected whistleblowers.

There might be ways of moving this situation forward.

This list has been adapted from an excellent article entitled, “Ten years of public interest disclosure legislation in the UK: are whistle blowers adequately protected?”, by David Lewis [Journal of Business Ethics (2008), 82: 497-507]

- Workers could be given a positive right to report concerns. However, the scope of reprisals is enormous, so imposing a contractual duty to disclose concerns may be difficult to enforce in practice.

- Workers should be protected if they raise concerns about serious wrongdoing even if it does not amount to a breach of a legal obligation. To know what is a legal obligation itself requires some knowledge of the law, and, with the cutbacks in legal aid, it may be impossible for an employee to obtain good quality legal advice.

- Workers should be protected not only if they have made a protected disclosure but also if they are victimised for attempting to make such a disclosure. There is noticeably no provision in the law for such victimisation, although victimisation is currently legislated for in a different context (the Equality Act 2010).

- Legislation could outlaw discrimination against whistleblowers at the hiring stage. Although cynics will argue that victimisation in the recruitment process can easily be concealed, Parliament has already marked its disapproval in relation to discrimination on the grounds of sex and sexual orientation, race and religious belief, age, disability and trade union membership. The major difficulty about this is how enforceable this could be, and whether the system could cope with genuine complainants who felt they had cause for umbrage. It could be that an employer might not take on a new whistleblower, regardless of his or her previous history as a whistleblower, and an employment tribunal might prefer to take on the side of the employer in such circumstances upholding a presumption of innocence. A solution might be for individuals, with a past history of whistle blowing, to have no obligation to put it down on employment applications, but this might undermine the mutual duty of trust and confidence even before the employment contract has started. Such a philosophy though might be in keeping with the philosophy of ‘spent convictions’ in the rehabilitation of previous offenders legislation.

- There should be no investigation of a person’s motive for making a disclosure? Here the critical issue is why the individual had intended to make a disclosure rather than a motive of why a person wanted to make a disclosure. This would bring the PIDA into line with the current jurisprudence of establishing the mens rea in the criminal law? A perfect valid intention, legally proportionate in its justification of promotion of patient safety, might be to prevent any further harm to patients. Workers should be protected if they have reasonable grounds to believe that the information they disclose is true or “likely to be true”? The “likely to be true” could lower the bar for a whistleblower to make a complainant, otherwise a whistleblower might simply wait until the ‘case’ against the employer is ‘water tight’, when the risk of harm to patients is still materially significant.

- There could be a statutory duty on employers to establish and maintain adequate effective reporting procedures? Legislation might also ensure that authoritative guidance (for example, via ACAS) is provided about the role and contents of such procedures. Clearly, there has historically been a problem with clinical regulators sharing information about risks to persons to patients, and this problem has caused unnecessary delay and confusion in the system.

- Union representatives could become prescribed persons so that workers who raise concerns with them would be protected. In future, it is hoped by some that union representation might become more easily available in both the private and public sector?

- An actual Public Interest Disclosure Agency could be established. Such an agency might receive disclosures, arrange for their investigation by an appropriate authority, provide advisory and counselling services and protect whistle blowers from reprisals. Whistle blowers have often complained how quickly the system has been to label their genuine concerns as ‘vexatious’. Such a body could build up experience and specialist expertise, through valid mechanisms for organisational learning, for spotting ‘genuine cases’ early, and for dealing with them speedily.

Reprisals against the whistle blower

One of the most important aspects perhaps is that out English legislation should relieve individuals of civil and criminal liability for making a protected disclosure.

At present it would appear that if a reasonable belief turned out to be incorrect, defamation proceedings could be brought against a worker who has made a protected disclosure. This is clearly ‘extremely problematic’, to put it mildly.

As regards possible retaliation, those who genuinely fear adverse treatment in their employment should be entitled to seek a transfer.It is unlikely that whistleblowers would wish for reinstatement into the organisation, to which they are devoted but have gone through hell in speaking out against.

Where workers have lost their jobs they should also have the option of choosing reinstatement or reeengagement somewhere else. It could be that some whistle blowers do want to rejoin the organisation they have been committed to, and clearly one of the defining factors here is the genuine attitude of the employer. Unfortunately, whistleblowers report a systematic exclusion from the activities of the organisation (e.g. no longer being invited to meetings, no longer appearing on organisation emails).

There could be specific statutory protection against post-employment detriments by outlawing victimisation which ‘‘arises out of and is closely connected to’’ the employment relationship. This would be entirely consistent with the notion that whistleblowers should be protected against all forms of discrimination, and would deal with the common problem of refusing to provide a reference.

In the last three years, the percentage of conciliated settlements has been rising in many jurisdictions. However, the PIDA average of 40.7% is well above the 28.3% average for all jurisdictions and second only to disability claims (44.7%). As regards withdrawals, the percentage in PIDA cases has been falling recently (30.8% in 2008/09), but this is generally in line with tribunal cases overall (33% in the same year) and the anti-discrimination jurisdictions.

Experience from other jurisdictions

Whilst the legal route is an important one, in the current ethos of rationing ‘access to justice’, it might be more valid in tackling the problem in its ‘root cause’ – i.e. by making it easier to speak out about problems in the NHS in an open and transparent culture.

However, whistle blowing poses formidable legal and ethical issues.

In some countries (such as Belgium and Germany) the political debate focuses on whether or not whistle blowing should be a protected right, whereas in other countries (such as the US, the UK and the Netherlands) the whistle blowing debate is more focussed on how to get more reports of wrongdoing in order to fight fraud.

In countries such as the UK and US, whistle blowing tends to be perceived as a duty and knowledge about wrongdoing as a liability.

It should be noted that in a 2003 Communication the European Commission acknowledged the part that whistleblowers can play in the fight against corruption and urged Member States to provide protection for them.

Subsequently three whistle blower organisations from Germany, Norway and the UK have requested the European Commission to take action.

The Commons Health Select Committee

The Commons Health Select Committee could not be clearer on their conclusions.

Thanks to Dr David Drew (@NHSwhistleblowr) for pointing me to the correct official published record of their findings (found here).

Firstly, they say that disciplinary fora and employment tribunals – inter alia – are often most the best place for a constructive airing for honestly-held genuine beliefs and concerns.

Secondly, they dispute whether the regulatory framework and contractual law work ‘well’ together to produce the current legislative framework.

Thirdly, the Committee were also clear on why and how there was tragically a place for ‘whistle blowing’ behaviour.

Thirdly, the Committee were also clear on why and how there was tragically a place for ‘whistle blowing’ behaviour.

Conclusion

As Simon Stevens takes up his new rôle as CEO of NHS England, I am sure he will wish to prioritise patient safety, organisational learning and transparency as key themes in moving the NHS further.

Whilst it is clear that the ‘sustainability’ myth of the NHS has taken foot to the detriment of a mature discussion about whether a safe National Health Service can be funded out of general taxation, it is clear that one thing is not sustainable in the NHS.

That is: the ballooning cost of successful NHS litigation claims AGAINST the NHS, and the personal cost to whistle blowers whose lives have been simply ruined. Their ultimate crime – working for the NHS, parts of which can be incredibly unsupportive to its employees, and wishing to speak out safely.

Possible further readings

Alford, C. F. (2007) ‘Whistle-Blower Narratives: The Experience of Choiceless Choice’, Social Research 74, 223–248.

Gunsalus, C. K. (1998) ‘How to Blow the Whistle and Still have a Career Afterwards’, Science and Engineering Ethics 4, 51–64.

Harris, C. E., Pritchard, M.S., Rabins, M.J. (2005) Engineering Ethics: Concepts and Cases, 3rd Edition (Wadsworth, Belmont, CA).

Near, J. P., Miceli, M. P. (1985) Organizational dissidence: The case of whistle-blowing. Journal of Business Ethics, 4: 1-16.

Oliver, D. (2003) ‘Whistle-Blowing Engineer’, Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice

129, 246–256.

Rothschild, J, Miethe, T.D. (1999) ‘Whistle-Blower Disclosures and Management Retaliation’, Work and Occupations 26, 107–128.

The Brave New Berwick World

In this gloomy world for socialists and the ‘reforms’ of the NHS led by the market (or, rather, McKinsey’s), there was much to welcome in the report by Don Berwick into patient safety and lessons from Mid Staffs. The beauty of the Berwick report was it attempted to take a measured, proportionate response, but Berwick advised in a subsequent interview with Victoria Derbyshire on #BBCNewsnight that it was not a time to be “fuelled up by anger, remorse or hatred about what happened”. There are people who are truly hurt by their experiences at Mid Staffs, and their pain will never go away, but at some stage the Kubler-Ross grieving process will have to progress from anger to acceptance in its natural time-course . It is not as if Mid Staffs ‘never happened’, but the Berwick report places Mid Staffs into a context which makes general, almost quite philosophical, conclusions about what happened, and, more importantly, how one might progress.

The starting point is that Don Berwick has not been drafted in as a Republican to spit bullets at ‘our National Health Service’ as the Medical Director, Sir Bruce Keogh, is fond of saying. In an almost trance-like state, Berwick was saying the NHS deserves to be the ‘best system in the world for patient safety’, and as a country we should rather pat ourselves on the back for a ‘comprehensive, equitable, free-at-the-point-of-use’ system almost spoken like a true socialist. These are, after all, words you only hear from mostly neoliberal politicians here in this jurisdiction through gritted teeth, while policy is geared up for back-door rationing of care in all of its market-led fairly subtle guises.

Berwick’s philosophy poses problems for those experienced in medicine and management. He seems to advocate a ‘learning from mistakes’ culture while promoting ‘zero fault’. Yet elsewhere in the document he does talk about patient safety in terms of realistic risk mitigation. Berwick also talks about ‘wilful neglect’, and appears to offer criminal sanctions in the most extreme cases of misconduct rather than incompetence. This is not so for the lay person to understand, unless you understand two things.

Firstly, it is very hard to take a prosecution for ‘wilful neglect’ under section 44 of the Mental Capacity Act against managers, quite distal in the ‘chain of command’, compared to individuals who provide frontline care. The implementation of ‘wilful neglect’ in practice is complicated further by the capacity issues of elderly patients; physicians will be guided by their own professional guidelines on the withdrawal of food and nutrition in palliative care, but will not wish to be at risk of committing a criminal offence under the new proposals. Berwick indeed refers to ‘criminal’ and other ‘legal sanctions’, meaning it is uncertain whether Berwick, who is not a lawyer, is contemplating a civil (on the balance of probabilities) or criminal (beyond reasonable doubt) burden of proof.

Secondly, it could be that Don Berwick has really at the back of his mind ‘wilful blindness’, a concept popularised by Margaret Heffernan in relation to senior people in management turning a blind eye to misfeasance lower down in the organisation. Extreme misconduct was a feature of senior mangers in ENRON, and, in the end, the US had to legislate the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, to counter this toxic culture. Berwick is able to complete his analysis by indicating where this toxic culture has come from. Berwick clearly posits it is some managers who have ‘gamed the system’, working with national politicians who have not given frontline staff adequate resources. He feels that frontline clinical staff have ‘copped the blame’ for this, and they should in future not be frightened to speak out if they feel they have been given inadequate tools to do the job in hand.

An issue at the forefront of Berwick’s mind is not adding to the overwhelming bureaucratic and legal demands of the NHS. He feels the regulatory system is overly complex anyway, and clearly alludes to the potential that, with the regulatory bodies having duplication of duties, there could be a lot of ‘buck passing’ going on. This has been a problem with clinical staff whistleblowing about inadequate resources, or indeed a ‘duty of candour’, which theoretically are already part of the code of conduct of professional bodies. A clear solution to this would be to encourage sharing of information between the regulators, and Berwick sensibly proposes this. One does wonder though whether his idea of a ‘superregulator’, as also proposed for the legal services sector, has ‘any legs’. Berwick completes his analysis that people have been much more concerned about impressing the regulators and politicians, than the main focus: they should be more concerned about patient safety, then delivering shoddy care through depleted, exhausted frontline clinicians on the cheap, but which is personally very rewarding for them.

Berwick’s overall solution actually could have been suggested in the US jurisdiction, and indeed there is a lot of evidence both here and in the US to support it. That is, to listen to patients first, and to be open about a NHS driven by a real culture of organisational learning. How we get from what we have now to this Brave New Berwick world, requires us to do textbook change management, e.g. “unfreeze”, “change”, “freeze” as described originally by Kurt Lewin, and later elaborated on by Kotler and others. This is possible if done properly, but given the cack-handed way in which the entire NHS reforms were implemented, this could go dreadfully wrong. Whilst the headline media accounts emphasised that “Berwick does not call for a minimum staffing level”, Berwick clearly sees a link between safe staffing and patient safety, which in all fairness is impossible to deny.

The “Brave New Berwick World” is surprisingly apolitical, but it does put the patient and the frontline staff first. It will be ultimately for those in the legal and medical professions, their regulators, and management as a professional body, to work out their responses. Berwick has often highlighted the ‘waste and inefficiency’ of the US system, which is ironically exactly where we are heading with our newly outsourced, marketised and privatised NHS. Berwick, despite media taunting, has tried not to state the size of the NHS as a weakness, in that he feels that one of the beauties of the NHS is that if a part of the NHS runs into problems it can call on the skill and expertise of another part.

The philosophical difficulty that Berwick will have, in giving some prominence to organisational learning, will be fully to embrace the heterogeneity of the NHS. The ‘zero fault’ methodology in patient safety was first popularised in anaesthetics, parking aside its history in the aviation industry. It may therefore be harder to apply in areas of general medicine where risk is a more pervasive theme such as oncology. All anti-cancer drugs have risks, for example, and not treating cancer (whatever type) has a risk of its own. Secondly, ‘learning from mistakes’ means one thing to experts in patient safety, but means something totally different in other areas of NHS management, such as innovation. The NHS has even toyed with rewarding managers who make mistakes in innovation to reward the process of experimenting.

But Berwick should be congratulated in introducing us to his “Brave New Berwick World“. Whilst it may have left scalp-hunters somewhat disappointed, there is a lot of substance in this very brief report that can be constructively discussed.

A ‘paradox of regulation’ in the NHS has opened the neoliberal floodgates

At 493 pages, the ‘Health and Social Care Act’ is a massive piece of legislation. Writing a blogpost on it would be like trying to summarise the contents of ‘War and Peace’ in a single tweet. From that perspective, it might seem as if the NHS is over-regulated, and certainly the number of guidelines and policies relating to the NHS has exploded. The Act has no provisions on patient safety, apart from the abolition of the “National Patient Safety Agency”, and yet Monitor is expected to publish a huge armoury of regulation of ‘competitive activity’ in the market. The full-frontal marketisation, together with outsourcing and privatisation of the NHS, is considered totally unacceptable to many reasonable onlookers, especially socialists. Market failure is a very important concept in economics, on the other hand. Market failure is a concept within economic theory describing when the allocation of goods and services by a free market is not efficient. That is, there exists another conceivable outcome where a market participant may be made better-off without making someone else worse-off. Market failures can be viewed as scenarios where individuals’ pursuit of pure self-interest leads to results that are not efficient – that can be improved upon from the societal point-of-view. The first known use of the term by economists was in 1958, but the concept has been traced back to the Victorian philosopher Henry Sidgwick. The general consensus, now, is not that there is a desperate drive for yet ‘more regulation’ at any cost, but there is a need for a higher standard of effective regulation in the NHS, to which not only top CEOs in NHS management can have full access. This is particularly poignant since the volume of budgeted NHS litigation claims has in fact exploded in recent years.

There is an ideological divide between those on the left-wing and those on the right-wing. The Conservatives promoted themselves on ‘light touch regulation’ at roughly the same time as the Financial Services and Markets Bill was going through parliament. There are two crucial issues now for the adequate regulation of the NHS. Firstly, all parties have a concern in patient safety. The previous failures of the Health Service Ombudsman’s office and that of CQC could be, and even now possibly, be pinned down directly on a lack of sufficient resources needed for them to fulfil their functions, and existing staff there would prefer not to amplify any suggestion that they are failing patients. Neoliberals also have an interest in patient safety, as failures in patient safety threaten competitive advantage, ultimately the profitability of private healthcare companies. Secondly, the failure of adequate market regulation in the water industry (and indeed the privatised utilities) still remains powerfully sobering for any ‘users’ of the National Health Service, a group within the general public formerly known as ‘patients’.

Employment is the first clear example of the ‘law in action’ in the NHS. The NHS, by its own admission, has decided to use compromise and confidentiality agreements in settlement with outgoing employees to prevent them pursuing unfair dismissal claims as is their statutory right. When it comes to a minimum staffing level, the usual riposte from the Right is that the complete answer involves ‘the staffing mix’. However, this is disingeniously to divert from the issue that there is an unsafe staffing level. Despite the fierce debates about the use and statistical reliably of hospital standardised mortality ratios (HMSRs), the clear evidence is that unsafe doctors:bed ratios can shove up the HSMR for weekends both in this jurisdiction and abroad (Dr Foster report 2010-2011, Prof Brian Jarman (personal communication by twitter.)) While the Left (and the Unions particularly) see the minimum staffing levels of nurses as ensuring a safe minimum standard for hospital safety, the Right (and neoliberals) invariably see the safe minimum staffing level as part of ‘the race to the bottom’ to maximise shareholder profitability. Staffing remains the number one issue where more effective regulation in the NHS could make a massive impact on patient safety, and indeed it is likely that this will be addressed as well as the legal duty of candour for hospitals, in Don Berwick’s wideranging report due out tomorrow.

The turbo-charged implementation of the economic market, rejected by true socialists, presents formidable problems for the regulation of the NHS. Traumatic lessons from other sectors, especially the privatised utilities, are particularly helpful here. There are currently twenty one private water companies operating in England, answerable to their shareholders. They are overseen by economic regulator OFWAT. Before 1989, water supply in England and Wales had been in the hands of 10 public regional water authorities, which were then sold off. They are private companies, many are owned by banks, private equity firms or foreign investment funds, like the main supermarkets.Thames Water, for instance, has been owned by Kemble Water Holdings – an investment consortium led by Australian banking and finance group Macquarie, with recent shareholdings taken by the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority and the China Investment Corporation. This democratic deficit of course makes many people angry, whereas the Unions have been the target of malicious smears from virtually all sectors of the media. Similarly, when Cheung Kong Infrastructure was buying Northumbria Water at the end of 2011, it sold Cambridge Water to South Staffordshire Water. South Staffordshire is wholly owned by the US based Alinda Infrastructure Fund.

OFWAT calculates the average water and sewerage bill in England and Wales at £340 for 2011-12, compared to £236 when water was privatised in 1989-90. The Health and Social Care Act and the regulations for implementing it change the nature of the NHS to allocate NHS resources into the private sector, to maximise profitability for shareholders. Private competitive tendering as the default option has seen major contracts being awarded to private sector corporates. The tragedy of this is that some private providers have an atrocious performance record in outsourcing, but because they are able to make slick bids appear to be implementing a ‘winning formula‘ in rent seeking behaviour from the current neoliberal Coalition. Priorities change from patient care to ensuring corporate rights, from spending directly on health care to investor dividends. The UK NHS becomes much more like the corporate-benefit US health care system which has very high spending while many people have no health care.

Any Qualified Provider is a procurement model that CCGs can use to develop a register of providers accredited to deliver a range of specified services within a community setting. The model aims to reduce bureaucracy and barriers to entry for potential providers. The US/EU free trade agreement has been launched, formally called the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). When TTIP negotiations are completed, unless the neoliberal Coalition manage to negotiate successfully an exemption for the NHS, corporations will have the right to sue the UK government for any attempts at ‘reversals’ that limit future corporate profits. In terms of “ownership”, most of our power generating companies, our airports and ports, our water companies, many of our rail franchises and our chemical, engineering and electronic companies, our merchant banks, an iconic chocolate company – Cadbury, our heavily subsidised wind farms, a vast amount of expensive housing and many, many other assets, all disappeared into foreign ownership. No mainstream party appears to be making any progress in this. Debbie Abrahams, Labour MP for Oldham East and Saddleworth, as a lone voice almost, has lodged a question from David Cameron regarding what exemption (if any) has been negotiated (recorded in Hansard here), and it turns out that Debbie Abrahams has now received a rather unclear reply.

In the EU, there are concerns that liberalising public procurement markets, combined with measures to protect foreign investors from government action, could constrain the power of national governments to decide how public services are provided. Concerns about the status and future of the NHS have been raised in the UK by people from many quarters other than in the Socialist Health Association. In particular, some commentators have claimed that measures to open up the NHS to competition would be made irreversible under the TTIP if its investor protection regime required US companies to be compensated in the event of a change of policy. This is of course a very dangerous situation. The liberalisation of the NHS market through the US-EU would be accelerated through a US-EU Free Trade Agreement. This is something which some corporates have been working very hard on ‘behind the scenes’. To dismiss this issue as scaremongering by the Socialist Health Association, which is supposed to uphold socialist principles and oppose further marketisation and privatisation, would be to turn a blind eye to all the legal evidence and judgments.

The legal arguments against further privatisation of the NHS are overwhelmingly strong, and there is a distinct lack of effective regulation of the NHS currently. Such poor regulation, whilst a boon for profiting private health providers, offends what is actually in the ‘best interests’ of patients.

This should massively concern socialists.

We can’t go on like this.

Where was the Big Society last week in the parliamentary discussion of the Keogh report?

The Big Society was the flagship policy idea of the 2010 UK Conservative Party general election manifesto. It now forms part of the legislative programme of the Conservative through the Liberal Democrat Coalition Agreement. Its stated aim was to create a climate that empowers local people and communities, building a “Big Society” that will take power away from politicians and give it to people.The idea was launched in the 2010 Conservative manifesto and described by The Times as “an impressive attempt to reframe the role of government and unleash entrepreneurial spirit”. The plans include setting up a Big Society Bank and introducing a national citizen service. The stated priorities were to give communities more powers (localism and devolution), encourage people to take an active role in their communities (volunteerism), transfer power from central to local government, support co-ops, mutuals, charities and social enterprises, and publish government data (open/transparent government).

The Big Society remains as vague now, as it did then. Localism has clearly been a frustration of ‘communities taking action’. Both the ‘Save Trafford A&E’ and ‘Save Lewisham A&E’ have been on the receiving end of an argument which urges the need for responsible reconfiguration of NHS services.Whilst campaigners in both situations have urged the need for recognition of their own services, the constant rebuttal has been that in any policy formulation or consultation there are bound to be dissenting views particularly if the sample size of respondents is high. Many people will share the frustration of those who had been encouraged by mechanisms such as the Localism Act (2011), in wider local issues.

There has been a big drive also to encourage ‘social value’ in public services, manifest in the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012. The fundamental idea behind ‘social value’ is that it is a way of thinking about how scarce resources are allocated and used. It involves looking beyond the price of each individual contract and looking at what the collective benefit to a community is when a public body chooses to award a contract. Social enterprises are businesses that exist primarily for a social or environmental purpose. They use business to tackle social problems, improve people’s life chances, and protect the environment. Healthwatch England has referred to “The NHS Bodies and Local Authorities (Partnership Arrangements, Care Trusts, Public Health and Local Healthwatch) Regulations 2012″.

In relation to the section covering political campaigning, their view is that,

“section 36(2) ensures local Healthwatch has the necessary freedom to undertake campaigning and policy work related to its core activities and believe to do otherwise would be distracting. We do however, appreciate how there could be some confusion due to the nature of the wording in the section.”

Another issue is how failing Trusts have been allow to provide poor care for members of the general public. Accusations have been made of a poor ‘culture of care’, and this issue has become political with accusation-and-counteraccusation. Patient groups are vital in representing the views of patients accurately. I know, because I was resuscitated after a cardiac arrest and successfully kept alive for six weeks in a coma at the Royal Free Hampstead. However, more than a decade ago, I studied my basic medical degree at Cambridge and Ph.D. also in early onset dementia there. The concern is that Trusts are not being altogether transparent in their metrics about care. However, I personally think patient groups to do this responsibly should be free to campaign on behalf of patients for poor care, but without turning the public against all hard-working doctors and nurses. My experience was that junior doctors and nurses feel terrible about episodes of poor care, so they definitely wish to work with the patient groups. This is not at all a ‘them against us’ issue, but the language of ‘service user’ and ‘they’re providing a service we pay for’ have not helped in this narrative, perhaps together with a concept that clinicians ‘carry out orders to maintain managerial targets’. This concept is particularly toxic, as it might appear at first blush consistent with a growing trend towards the deprofessionalisation of medical Doctors and nurses. Patient groups do an extremely worthwhile rôle, and I have the highest regard for them.

This is why it is all the more important I feel that these issues about the NHS can be held in future in a dignified and balanced manner, without further talk of Hunt ‘politicising the NHS’ or an ‘active smear campaign against Andy Burnham’. Patient groups need to be carefully about their involvement in the media, otherwise they can easily become politicised. The academic issue of whether HSMRs are reliable has become politicised, although the academic debate about HSMR is safely ringfenced in the academic journals such as the British Medical Journal. The limitations of the claims of ‘excess deaths’ or ‘needless deaths’ always needed to be done carefully, and it was left to Sir Bruce Keogh himself and media sources not particularly known for their Conservative loyalty, such as the Guardian or New Statesman, to defuse the panic which had set in following irresponsible reporting of the Keogh mortality report at the weekend.

Political campaigning is defined by the Charity Commission is as follows:

Campaigning: We use this word to refer to awareness-raising and to efforts to educate or involve the public by mobilising their support on a particular issue, or to influence or change public attitudes. We also use it to refer to campaigning activity which aims to ensure that existing laws are observed. We distinguish this from an activity which involves trying to secure support for, or oppose, a change in the law or in the policy or decisions of central government, local authorities or other public bodies, whether in this country or abroad, and which we refer to in this guidance as ‘political activity’.

Further details are given as follows:

“Political activity, as defined in this guidance, must only be undertaken by a charity in the context of supporting the delivery of its charitable purposes. We use this term to refer to activity by a charity which is aimed at securing, or opposing, any change in the law or in the policy or decisions of central government, local authorities or other public bodies, whether in this country or abroad. It includes activity to preserve an existing piece of legislation, where a charity opposes it being repealed or amended.”

It would seem therefore that the definition of ‘political activity’ is not the same as the “rough and tumble” of politics seen in House of Commons debates, nor even on Twitter. However, it is really hard to know what ‘changes in the law’ might follow from Keogh or the Francis Report. This in part, one must to be admitted, needs clear definition what an appropriate ‘outcome’ might be. If the aspiration is “safe staffing”, serious consideration should be put into how enforceable this is, how it could be measured. and what sanctions might follow from an offence regarding it. A clear problem is that stakeholders will always have different views, particularly if there are more of them, and resolving conflicting views is especially difficult. This is all the more significant if you hope a ‘motherhood and mother pie’ approach in keeping with that ‘flagship policy’ of the Big Society. It is clear that some patient groups, indeed the Government, oppose a flat ‘minimum staffing level’ for perfectly rational reasons:

Christina McAnea, UNISON head of health, said this week:

We are pleased that the Keogh Review, as the Francis Report before it, has recognised the relationship between quality care and safe staffing levels. UNISON has been campaigning for safe staffing levels and the right skills mix on wards for many years. This includes in the evenings and at weekends – there is clear evidence that out of hours cover isn’t safe. It is time for the government to start listening and take action by committing to minimum staffing levels. They must also listen to staff and patients who are the best barometer of an organisation.

Spending pressures mean that health workers are losing their jobs. Financial pressures are building up in the NHS just as the demand for healthcare and its cost is rising – trusts are being asked to make obscene savings. Undoubtedly, this will hit standards of patient care hard, and is the direct consequences of decisions made by the government – not by hardworking NHS staff.”

Whilst one clearly not make everyone happy all of the time, it is fortunate that there are so many brilliant stakeholders who ultimately want the best of patients in the NHS. The purpose of the English law is obviously not to get in the way of all the people participating in English health policy at this particularly sensitive time. Politicians can help too by not turning people against other people, and members of the public can help too by not doing the same.

Safe staffing, Keogh and the Nursing Times “Speak out safely” campaign

Despite clear differences in opinion about what has happened in the past, patient groups, Andy Burnham, Jeremy Hunt, the Unions, bloggers, experts, other patients, whistleblowers, and relatives at face value appear to want the same thing: a safe NHS where you do not go into hospital as a risky event in itself. The issue of safe staffing in nursing has become the totemic pervasive core issue of secondary care safety, and no amount of parliamentary time one suspects will ever do proper justice to it. In reply to a question from Valerie Vaz, who is herself on the Health Select Committee, Jeremy Hunt immediately quoted the Nursing Times and the Francis Report (from Tuesday 16 July 2013):

The aim of the Nursing Times’ Speak Out Safely (SOS) campaign is to help bring about an NHS that is not only honest and transparent but also actively encourages staff to raise the alarm and protects them when they do so.

They want:

- The government to introduce a statutory duty of candour compelling health professionals and managers to be open about care failings

- Trusts to add specific protection for staff raising concerns to their whistleblowing policies

- The government to undertake a wholesale review of the Public Interest Disclosure Act, to ensure whistleblowers are fully protected.