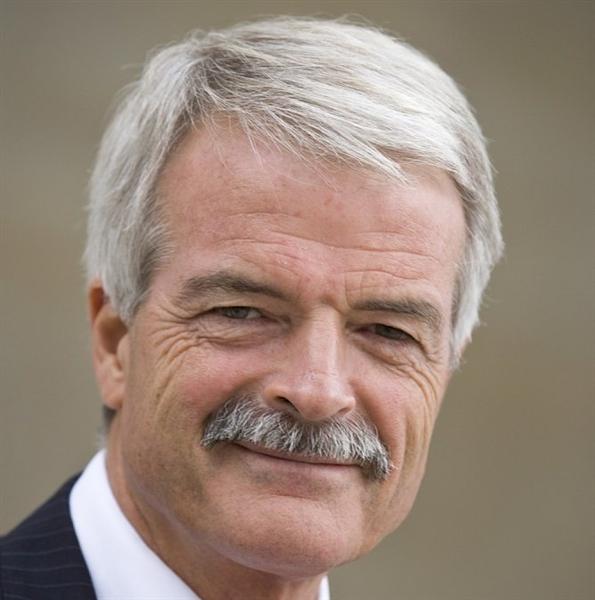

Sir Malcolm Grant is Chair of NHS England. He helpfully presented an overview of commissioning in the NHS under ‘clinical commissioning groups’ yesterday afternoon at Olympia. Grant was until very recently the President and Provost of UCL in London, having had an accomplished career elsewhere including at Cambridge.

Grant’s talk was an optimistic vision of how commissioning might work in this new era following the Health and Social Care Act (2012). He emphasised that the roll-out of CCGs effectively was “the dog that didn’t bark”. I asked a question whether he felt disappointed that the participation of GPs wasn’t greater in CCGs. Grant said, “If I’m being honest, yes”, which was a frank reaction to the observation that CCGs may not be ‘led’ by GPs and that indeed many GPs are unwilling to participate in the CCGs.

At first, Grant’s suggestion that there could be more providers on CCGs might seem ludicrous, but, in terms of policy, might reflect a genuine concern of the providers’ viewpoint to be expressed too. In any case, there are numerous allegations of GPs having ‘conflicts of interests’ in also sitting on CCGs for the commission of services where they potentially have a direct financial interest.

Part of the raison d’être of clinical commissioning groups, and actively promoted as a ‘catalyst for change’, was that primary care physicians could ‘drive’ commissioning. The history of CCGs, however, can be delineated from two sources. One is the evolution of health maintenance organisations in the US, and the second is Pirie and Butler’s “The Health of Nations” discussion document for the Adam Smith Institute a while ago.

CCGs are functionally insurance bodies which assess risk in a given population. Grant cited that there had been great flexibility in the population sizes being served by CCGs. In insurance terms, there is nothing particularly emotional about it, however. The greater the size of population, the more accurate your assessment of risk might potentially be.

One of the most striking suggestions by Grant was that the undergraduate medical curriculum could be much ‘shorter’, reflecting how easily information could be looked up on electronic search engines at the drop of a hat. Grant correctly pointed out that most of the audience probably had the equivalent of 32GB in their hand.

By suggesting this, Grant is of course admitting that ‘knowledge is power’, a sensible thing in itself. However, the narrative that ‘all information is knowledge’ is a dangerous one, given the sheer volume of irrelevant information.

Making decisions in the real world, in business management, has been much influenced recently by the field of ‘bounded rationality’, that fundamentally we have to make quite quick decisions having paid selective attention to parts of the world around us. When you do a Google search, you can’t possibly read all of the search results.

The drive towards a ‘quick medical course’, say 2 years rather than 6 years, comes from the idea that you could get rid of time wasted in learning material available elsewhere more easily. For example, a medical student would no longer be required to show a ‘fact dump’ of the point of origin, insertion, action and nerve supply of every muscle in the body? Likewise, a medical student would no longer be required to present every chemical involved in the biochemical cascade leading from activation of a particular receptor for a drug?

There is certainly a case that an undergraduate medical student learns a lot of useless information in 5-6 years, which is not good preparation for the pre-registration junior doctor jobs in a busy hospital, when other skills such as practical procedures or time management might be more beneficial. Certainly, even in the current curriculum, a medical student might do a maximum of one month in General Practice, or one clinical lecture on dementia and delirium.

It is also, unfortunately, the case that, at many medical schools, the preclinical medical school is overloaded by overly detailed lectures by basic scientists expert in their fields (but these scientists have never seen a patient in their life.)

A ‘provider’ offering a short medical curriculum might have business ‘competitive advantage’ as a shorter curriculum is likely to be shorter and cost less. The General Medical Council will of course wish to ensure that the end-product of a short medical course is a Doctor who is safe for the public.

A short medical course could therefore be a ‘genuine disruption’ which dislodges the power of the ‘incumbents’. In other words, one simple change to the way the medical curriculum is changed to focus on skills of learning how to learn rather than sheer volume might benefit the student and public alike. Grant, correctly perhaps, feels that the emphasis should be on lifelong learning through CPD (and to extend his concept lifelong regulation through mechanisms such as ‘revalidation’).

At worst, the short medical curriculum could be interpreted as a ‘race to the bottom’, reducing the ‘barriers to entry’ in educational provider, producing Doctors at high volume and low cost. This might lead to a glut of unemployed Doctors. The needs of individual Doctors are not higher than the needs of the profession, but it is a valid presumption that the public prefers Doctors to be as highly skilled as possible.

Anyway, it is clear that Sir Malcolm Grant has not got an attitude of ‘mission accomplished’, but instead Grant seems genuinely fired up about all his challenges ahead.

Pingback: Is Sir Malcolm Grant's new idea of a short medi...()