You are advised to read this article in bits, according to which parts interest you. If you would like to engage constructively in some of the issues here, I can easily be reached on my twitter thread @legalaware

Introduction

There are potentially very many false dichotomies in the debate over English healthcare: private vs public, efficient vs inefficient, etc. While we wait to halt the privatisation of the NHS, it might be better for our morale to think positively that some private healthcare providers are choosing different chocolates, rather than picking cherries, but ultimately the purpose of the State might be to aspire to cover all illnesses, irrespective of financial ability to pay, and this is of course a very admirable one. The problem is: in an unfettered market, the equilibrium will simply be the conditions which are most profitable for providers are ‘covered well’, but in the new-look NHS (“Neo NHS”), some conditions will be massively under-represented and could become very costly for CCGs covering these patients?

Whenever you introduce a market, you will always experience the phenomenon of “cherry picking”. The question in the short term must be: what do we do with the fact that certain companies will wish to pick their cherries, so that directors can fulfil their statutory duty under s.172 Companies Act [2006] to “promote the success of the company”, i.e. maximise shareholder dividend. For some reason, the electorate does not wish to be open about the privatisation of the NHS, even though market-oriented health care reforms have been high on the political agenda in many countries (e.g. Erik M. van Barneveld and colleagues, 2000). The response of the left tends to be a binary ‘boom-or-bust’ approach; for example, having the Act repealed, having no markets etc., and ideally ‘in moving forward, I wouldn’t start from here‘. The problem however is that we can all become trapped in ideology, and become attached to fundamental principles. Some would say that some issues are “clear red line” issues such as comprehensiveness or totality of the NHS, but, in light of the ongoing active discussions about rationing, it is clear that certain issues need to be confronted sooner rather than later. This article will consider how ‘cherrypicking’ has been addressed, and possible ways of dealing with it. It is only meant to be an introduction to this complicated issue, however.

Use of the term “cherry-picking”

One of the criticisms made about the NHS privatisation is that the outcome of the process will see some providers “cherry-picking” services. The issue about this term is that it sounds pejorative, even if this is your image of a bowl of cherries:

Legal origin of cherry picking as a concept

The legal use of the term “creamskimming”, in a different jurisdiction (the US), appears to have originated in a 1951 Supreme Court case, Panhandle Eastern Pipe Line Co. v. Michigan Public Service Commission [1951].The appellant Panhandle, an interstate gas pipeline company, launched a program to secure for itself large industrial accounts from customers already being served by the Michigan Consolidated Gas Company, a local distribution company franchised under Michigan law. The Supreme Court of the United States refused to grant Panhandle a purported “right to compete for the cream of the volume business” within Consolidated’s customer base “without regard to the local public convenience or necessity.”

Jim Chen has provided that the following definition of ‘cherrypicking’ should be used:

““Cream skimming” should be defined as “the practice of targeting only the customers that are the least expensive and most profitable for the incumbent firm to serve, thereby undercutting the incumbent firm’s ability to provide service throughout its service area.””

Chen quickly goes onto say the following:

“The unfortunate truth is that regulated incumbents have long exhibited a tendency to condemn lawful, desirable competition simply by invoking the pejorative label of “cream skimming.” Alfred Kahn diagnosed the urge long ago: “if one defines as ‘creamy’ whatever business is worth competing for,” one will reach the absurd conclusion that “all competition is by definition cream skimming.”

Indeed, at the time of another massive NHS reorganisation in 1974, Alan Reynolds writing in the Harvard Business Review observed from the same viewpoint:

“Whenever a monopoly or cartel pleads with the government to ban or restrain competitors, it invariably accuses the newcomers of skimming the “cream” and leaving the less profitable business to established companies.”

“Cherry-picking” as a political (and otherwise) device has been an on-running theme in the discussions over the Health and Social Care Act [2012]. Cherry picking (sometimes also referred to as cream skimming) is a term that generally refers to the act of selecting only the best or most desirable candidates from any group. As Mark Armstrong explains, “It is a common regulatory practice to “assist entry”, especially in the early stages of liberalisation.” In the context of healthcare provision, it is typically used to describe instances where private healthcare providers select patients which are of the highest value and lowest risk to them, referring less desirable patients, those with conditions likely to require more complex treatment, back to the NHS.

As the Health and Social Care Act introduces markets to many more areas of the NHS, cherry picking is likely to increase. As as this increases, public scrutiny of it is likely to increase, and it’s pretty likely that private suppliers are already organising their PR for this. Indeed, Alan Reynolds (1974) had advised the following to (presumably predominantly corporate) readers of his article in the Harvard Business Review:

“Newcomers accused of cream skimming should force their accusers to be quite explicit about how much cream there is, where it comes from, and where it goes. Where did the monopoly get the mandate to run this [] program. What are exactly are the objectives? Is there a better way to achieve them. Who audits the results? Without such substance, the cream-skimming cliché has about as much credibility as an unsupported accusation that competition is unfair. There are plenty of epithets for those who charge low prices, but they relatively merit attention.”

The importance of the regulator

Cherrypicking poses a difficult problem for the regulators – as predatory pricing should not be confused with improved competition in financial markets, and may not in fact be illegal per se in some jurisdictions. This has been a “known issue” for some time, see for example the memorandum submitted by Monitor, the “sector regulator” dated 19th July 2011:

There was also concern that the Health and Social Care Bill would enable private providers to ‘cherry pick’ routine and less complex healthcare services and interventions that are cheaper to provide and more profitable. The concern was that this would leave the NHS to deal with the higher-cost, more complex and long-term conditions with inadequate prices, causing the destabilisation of local hospitals. A proposal has now been included in the Bill to address this concern, which means that Monitor would be given a specific duty to set prices that reflect underlying costs, so there should no longer be any cherries to pick. Cherry-picking should not be an issue if NHS prices are designed to reflect complexity of treatment so that appropriate payments are made for both simple and complex services.

In his latest advice to 38Degrees, David Lock indeed refers to “cherry picking”:

“Private providers will seek, for example, cherry pick services which are relatively cost-effective to deliver may be able to put pressure on the commissioner to divide out those services from others on the grounds that the private provider can provide those services more economically or that to bundle up these services with other services amounts to anticompetitive behaviour. This is likely to be an area of intense debate within the NHS as private providers seek to use the (in places unclear) wording of the Regulations to put pressure on CCGs to divide contracts. Some CCGs may be able to resist this pressure but others are likely to succumb to this pressure. It follows that whilst the wording of the regulations does not place any duties onCCGs explicitly to divide contracts, in practice this happen for the reasons outlined above.”

So there is patently a debate to be had. History has provided that there can be a huge problem in effecting market entry, and the only way you can achieve anything like ‘good competition’ is to avoid a situation with only a few suppliers. Cited in Armstrong (2000), the privatisation of BT is noted.

“In Britain, the first competitor was explicitly granted favourable access to BT’s network, and in particular was made exempt from making any contribution to BT’s access deficit (see DTI, 1991, page 70):

“it is reasonable to exempt a new competitor [...] from the [access deficit] contribution in the early stages of its business development, in the interests of helping it get started. If this were not done, the ability of the newcomer to compete might be inhibited because of the economies of scale available to the incumbent and competition might never become established.“

Cross-subsidies

A possibly way to address this is through the use of “cross-subsidies”?

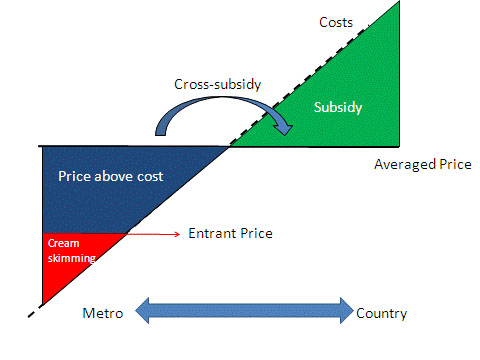

As shown here (diagram produced originally in http://www.ictregulationtoolkit.org/en/Section.3545.html) this could be a mechanism of addressing a potential market failure, but a cross-subsidy may indeed itself be anti-competitive when a firm with market power prices services in less competitive markets higher so that it can have lower price for services it sells into competitive markets.

The issue of “cross-subsidies” has been addressed in other sectors: for example: “Incumbents complain about “cream-skimming” competition allowed by the cross-subsidies above. So, regulators assist incumbents with price rebalancing to meet competition, which generally increases line rentals so that call prices can fall. This is a politically sensitive process because raising access prices disadvantages the poorer users who make fewer calls; so some policy direction may be needed.”

But politically, does admitting there are cross-subsidies constitute a failure of the market? This is again where the patient may not be given complete information. Indeed, unless you happen to be medically qualified, you will not share the level of information a clinician may have in making a decision about your own care. Like all other aspects, it is quite possible that the general public, i.e. real patients, will not be involved in this discussion, but it does indeed happen in other sectors, for example:

Respondents knew that cross-subsidising goes on – at least to some extent – in other areas. They knew, for example, that they paid some additional, albeit unknown, amount in the supermarket to cover the cost of shoplifting, breakages and in-store damage to goods. They suspected that the cost of insurance premiums must allow for fraudulent claims. They were less aware that train fares include a subsidy to cover revenue lost through fare dodging, or that mortgage rates compensate lenders for defaulters, or that electricity and gas customers in rural areas are more expensive to service than those in urban areas but the cost is spread across all customers. There was no awareness at all of a cross-subsidy in the water bill.

Payment-by-results?

The Government has decided to tackle this through “payment by results”. As Crispin Dowler and Dave West have recently reported in the Health Services Journal,

“Commissioners may need to increase the prices they pay to NHS hospitals left with more complex workloads after other providers have “cherry picked” the easier patients, new Department of Health guidance shows.

… Rules introduced this year gave commissioners the flexibility to cut the tariffs they pay to such providers, but did not mandate increased payments to hospitals that are left with disproportionate numbers of complex and costly patients.

However, the guidance for 2013-14 appears to endorse above- as well as below-tariff payments.

“Commissioners will be required to base any decision to reduce tariffs on clear evidence which shows that the provider would be over-reimbursed at the national tariff rate,” it states. “They must also give consideration to the potential for other providers to be left with an altered, more costly, casemix which may therefore also require a funding adjustment.”

As was indicated in the draft document published in December, the final PbR guidance also includes a list of high-volume procedures that may be more susceptible to “cherry picking”.”

Conclusion

So, what should the response be from an organisation interested in socialism? There is no doubt that this discussion has advanced well beyond “whether it’s marketisation or it’s privatisation”. The legal instruments will come into force on 1 April 2013, and this article has no intention of proposing a campaigning thrust for ‘saving the NHS’. However, what has been presented here has been some indication of the language of ‘cherry picking’, what the potential issues about ‘cherry picking’ in markets might be, and how these might be mitigated against by the regulators. The problem is: in an unfettered market, the equilibrium will simply be the conditions which are most profitable for providers are ‘covered well’, but in the new-look NHS (“Neo NHS”), some conditions will be massively under-represented and could become very costly for CCGs covering these patients? Time will tell how this evolves.

Further reading

February 2000: Mark Armstrong (Nuffield College, Oxford OX1 1NF) Regulation and Inefficient Entry.

Department of Trade and Industry (1991), Competition and Choice: Telecommunications

Policy for the 1990s, London, HMSO.

Alan Reynolds. November – December 1974. A kind word for cream-skimming. pp.113-118.

Erik M. van Barneveld, Leida M, Lamers, Ren6 C.J.A. van Vliet and Wynand P.M.M. van de Ven. (2000) Ignoring small predictable profits and losses: a new approach for measuring incentives for cream skimming. Health Care Management Science 3: 131-40.

Pingback: If the NHS is not a market, why do we even bother to regulate it like one? - Socialist Health Association()