Home » NHS reorganisation

If the NHS is like a human brain, we may have to think about reconfigurations a bit differently

The human brain is probably the most complex organ of the body, and comparing it to the National Health Service may give us conceptual hints as to how we approach reconfigurations.

The brain cannot undergo limitless growth in response to increasing demand, which may or may not increase as a person gets older.

This is shown for example by the fact that it’s contained within a skull. It has an outer covering which encases it. This is known as the ‘blood brain barrier’ regulating traffic between the body and the brain, analogous to the regulators.

Seeing what is happening from output this barrier can be a good marker of the quality of activities within the brain itself.

The brain makes decisions, plans ahead, makes decisions, has a working memory, can learn, has memory for events, and is able to perceive aspects of the world around it.

Also bits of it can suffer from a build-up of toxic metabolites, which may be kept hidden.

It needs a brainstem to survive, which for example contains centres that control our breath. This brainstem also connects the brain to the rest of the body.

We of course need lungs to breathe. In the same way, the the NHS needs the rest of the economy to survive. And we can’t absolutely divorce what is happening in the NHS from the rest of what is happening in the UK, in much the same way the brain cannot be thought to be separate from lungs. There’s an interdependency.

The human brain is incredibly metabolically active. Without being given adequate resources, the whole thing will simply die.

The body needs to work too. For example, if we can’t breath, we don’t get the oxygen to run the brain. If there is insufficient monies to run the NHS, of the order of billions, it will simply fail.

No-one really understands the complexity of the brain, in a similar way to not many people understand how the NHS works as a whole. There are thought to be 100 billion brain cells, in various proportions of the types of brain cells.

With so many brain cells, and connections between them, it’s inevitable that some connections (and even brain cells) will become “redundant” with time.

The number of each category of brain cells doesn’t matter as such as long as the whole brain functions well. However, some people worry that certain types of brain cells, or entities in the NHS, consume too much energy and are not particularly efficient. This is of course of concern if you’re thinking about having enough energy for the brain as a whole.

It’s likely that no one part of the brain fulfils a certain function in the brain, such as decision making. It’s likely that different parts of the brain work in synchrony to fulfil these functions. However, some parts of the brain may be more important than others for producing certain brain functions.

This is possibly helpful to think about what happens when some parts of the brain fail.

Some parts of the NHS may be running a deficit in a moribund way before they enter an outright failure regime.

In the same way, it could be that some parts of the brain don’t have enough oxygen – maybe insufficient money or spending too much money, and so forth. Lack of oxygen can produce a stroke.

The question is what happens when a part of the brain has a stroke. Somebody has to ascertain that that part of the brain has no residual function left.

Who makes that diagnosis, that there’s no function left, and no amount of oxygen will make that brain part work, is bound to be controversial, as to the subsequent management step of allowing that brain part to go peacefully out of action.

A problem obviously arises if it’s decided that that ‘out of action’ brain part goes into managed decline too quickly.

It could be that that part of the brain is actually critical for a function from the brain. This could be the case for a particular entity in the NHS itself too.

If a part of the brain is truly dead, the rest of a network of other parts of the brain could be recruited to fulfil that function. Such plasticity is known to a limited degree in the adult nervous system, but is much easier in the developing nervous system.

Brains which are old depend on activity in parts of the brain to determine where the connections are strongest and best made.

This is fundamentally the ‘issue’ for socialists who think that activity can determine some NHS services going into ‘managed decline’ through a mercenary neo-Darwinian ‘survival of the fitness’ process.

A problem with Lewisham, originally, was that it appeared that bits of the brain, to overegg this analogy, were being shut down because other parts of the brain had failed. This is of course counterintuitive.

It could be through proper planning can we can work out how to reconfigure networks so that the brain is still able to provide all its functions.

A major problem with recent legislation is bits of the brain can now be shut down without proper analysis,

Another major problem is that there is enormous public distrust, so that people are uncertain that the brain will be given enough oxygen to carry out its functions.

But on a happier note, the brain is a bit unpredictable. It is a remarkably sophisticated organ. There’s a lot of affection for it which far transcends it being a ‘sacred cow’.

As it gets older, we need the very best sophisticated minds to work out how best to progress English policy. I am not absolutely certain we have them just yet.

The vision to lead the NHS

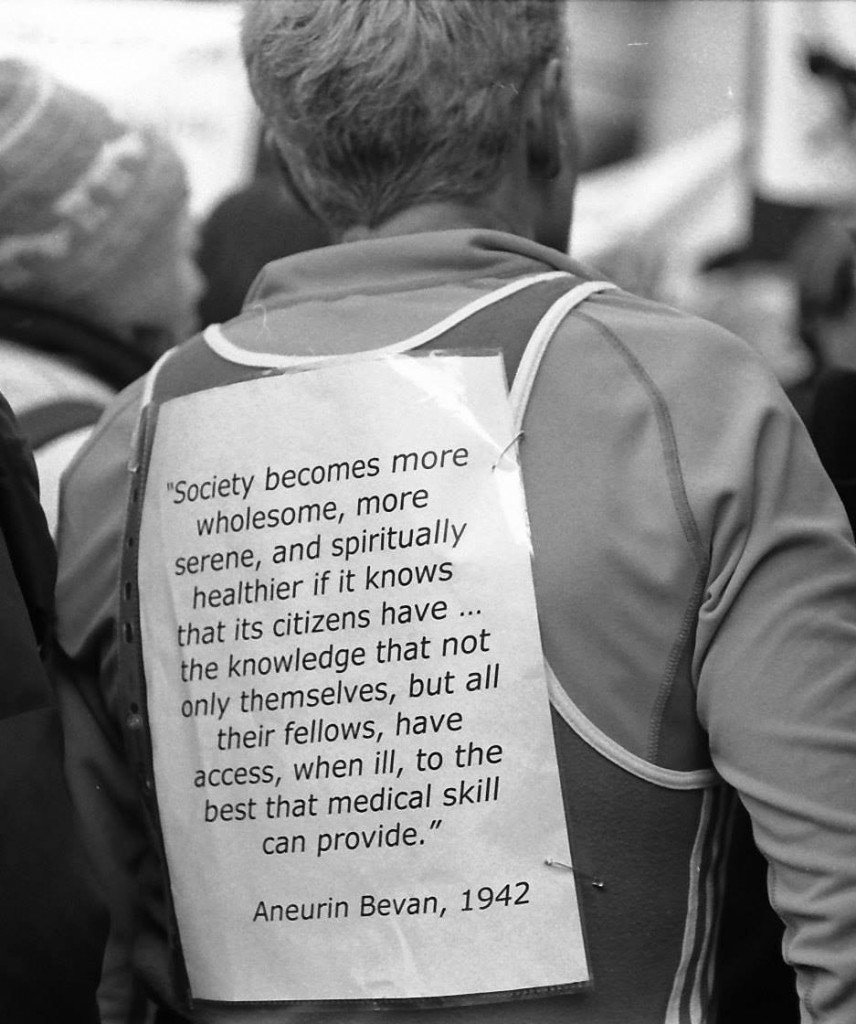

If you look at this person’s billboard, you’ll find a very short passage from Aneurin Bevan from 1942.

Aneurin Bevan had his critics too. Bevan would often comment that the Labour Party was not inherently socialist: citing that one in five members of Labour at the time were truly socialist.

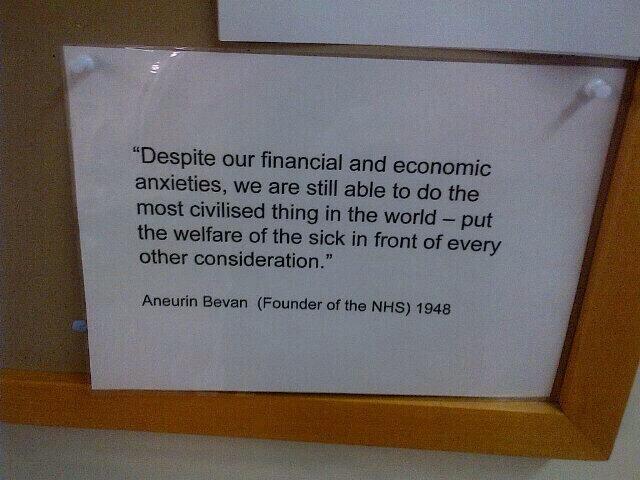

Still, Bevan and Attlee carried on regardless. Here’s a comment from Bevan from 1946.

Bevan left school at 13. He didn’t go to Charterhouse and Oxford.

The vision of the creation of the NHS is indeed one of the things which truly shocks critics of socialism. And for decades various Governments have been trying to undermine the National Health Service.

You can in fact tie yourself in knots over definitions of socialism, but certainly equality of opportunity for treatment and care (equitable access), solidarity, cooperation and collaboration might be strands. The idea of efficiently planning resources for the greater public good of the country might also be in the mix.

Lloyd George himself said it would be indecent for a democratic dictatorship to emerge from the National Government which had been put on a “war footing”.

Cameron and Clegg put us on a war footing, despite not having won the 2010 general election. But the war footing was to use the five years to extract as much money out of the public service and outsource it to the same bunch of people, as per outsourcing and privatisation of NHS, probation services, Olympics or workfare. These people are in the private sector.

Diverting resources from the public sector to the private sector is privatisation.

The result of this war footing for the NHS was an Act of parliament which did not have a single clause on patient safety, apart from the abolition of the National Patient Safety Agency; so it is rather ironic and foolhardy perhaps that Jeremy Hunt would wish to campaign on this issue.

The 493 page Act of parliament has been used to spin a number of lies, such as GPs being in the ‘driving seat’. CCGs, or clinical commissioning groups, are simply insurance schemes which apportion risk to local populations, and work out how much money should be alloted to them for their future care or treatment (and how it should be spent.)

They are conceptually the same as the “health maintenance organizations” (sic), borrowed from the United States.

The absurdity of it is that the NHS was borne out of the failure of private insurance approaches before the War, so why should we wish to return to an inequitable fragmented country which the Attlee government had tried so hard to repair?

That war footing for the NHS was a convenient way to shoehorn in that famous section 75 and its Regulations which provided the jet engine for a market – competition. This market needed to be ‘regulated’ (in as much as the cost of living crisis has demonstrated the failure to regulate an oligopoly of companies which can legally collude in setting prices). And there needed to be a régime for fast managed decline of NHS trusts.

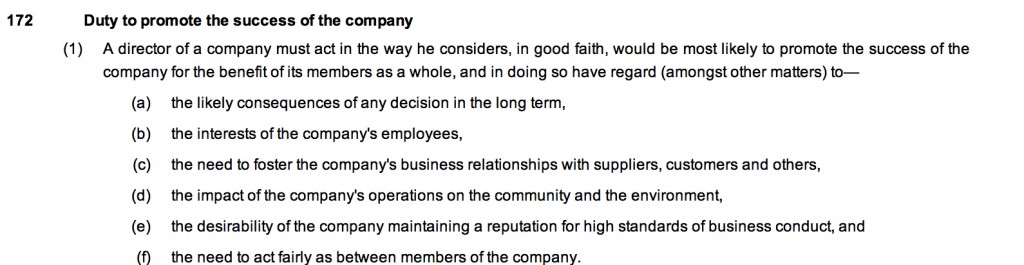

Private markets are fragmented, and always introduce “transaction costs” leading to waste and inefficiency. Directors of private limited companies have a primary duty to make a profit for their shareholders, and that’s the case even if you’re using the “NHS” as a logo or kitemark.

And you can take treatments out of scope. This is rationing. It happened under the previous Government, is happening under the current Government, and will happen under the next.

And it cost £3bn – money which could have been better spent elsewhere, such as on the frontline.

The myths keep on coming and coming and coming.

Who’s going to pay for the NHS going seven days a week? Are NHS Consultants simply going to accept a unilateral variation of contract with no mutual agreement? It might be a case of ‘see you in court’.

The next Labour government needs to set out a vision which can inspire the general public, and equally importantly inspire the staff of the NHS.

The staff of the NHS do not want to be told that ‘a culture of evil has become normal’ by the Secretary of State for Health. They want some dignity and respect too.

They don’t want a technocrat who can implement textbook ‘transformative’ leadership, such that they can turn their NHS Trust into the healthcare version of a motor car production plant.

They wish their views to be respected, and where they can speak out safely where something goes wrong.

Nobody’s ever dared to discuss with the public the effects of PFI on local economies, or the billions of efficiency savings, but, if indeed ‘transparency is the best disinfectant’, we need all major political parties to speak openly about this issue.

It might be that “clinical leaders” need to grow some balls where possible to neutralise some who are overly aggressive NHS management seeking to balance budgets and hit targets at all costs.

I’m sorry if this sounds like a rant more fitting for a left-wing version of Katie Hopkins (perish the thought).

But we need a vision.

That vision is the SHA.

Why yesterday’s Care Bill debate matters to tomorrow’s decision about Mid Staffs

s. 118 is the contentious clause of the Care Bill.

An important question is of course whether the Labour Party, if they were to come into government in 2015, would seek to repeal this clause if enacted. The likelihood is yes. What to do about reconfigurations and reconsultations for NHS entities which are not clinically or financially viable is a practical problem facing all political parties. A practical difficulty which will be faced by all people involved in the TSA process between now and 2015 is that it is relatively unclear what Labour’s exact legislative stance on the future structural reorganisation of the NHS is, save for, for example, having strongly opposed the recent decisions over Lewisham (prior to the High Court and Court of Appeal.)

Draft recommendations for the future of Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust were published on Wednesday 31 July 2013 by the Joint Trust Special Administrators. Tomorrow will see the publication of the final proposals (and it is widely expected that interested parties will be informed about the outcome of the consultation process this evening.) Producing a long-term outlook for key services, including paediatrics, ICU and maternity, is going to have been a complicated decision-making process for all involved.

Stephen Dorrell MP, Chairman of the influential Health Select Committee, pointed out in the Care Bill debate yesterday afternoon that the competition debate about the NHS is usually presented as ‘binary’, and this is to some extent reflected in John Appleby’s famous piece for the King’s Fund on how there are both advantages and disadvantages of competition. What people agree on more or less is the need to move beyond fragmented care to an integrated approach in which patients receive high-quality co-ordinated services. The idea is that competition itself need not be a barrier to collaboration provided that the risks of the wrong kind of competition are addressed. This will involve considerable legislative manoeuvring in the future. In securing a more integrated approach, reflected also in Labour’s “whole person care” ultimately, commissioners are expected not be able to fund ever-increasing levels of hospital activity.

Trying to keep frail older people away from hospital, and to allow such individuals to live independently, has become an important policy goal. Trying to keep people in hospital for shorter stays is another key aspiration. Matching services to actual demand is a worthy aspect of any reconfiguration (and also providing the full range of relatively unprofitable emergency services locally.) All of these factors become especially important with the increasing numbers of older people in the population, some of whom have multiple and complex chronic conditions that require the expertise of GPs and a range of specialists and their team. “Integrated delivery systems” in other countries have previously embraced a model of multi-specialty medical practice in which GPs work alongside specialists, often in the same facilities. It is possible that this sort of approach will become more popular in future here in the UK. It is relevant to the NHS here, because of the need for specialists and GPs to work together much more closely to help patients remain independent for as long as possible and to reduce avoidable hospital admissions.

A frequent criticism has been that ‘competition lawyers should not be blocking decisions which are in the patients’ interest‘. The problem with this argument is that simple mergers may not actually be in the patients’ interest. While mergers to create organisations that take full responsibility for commissioning and providing services for the populations they serve have been pursued in Scotland and Wales, the benefits of this kind of organisational integration remain a matter of dispute.

It’s been mooted that stroke care in London and Manchester has been improved by planning the provision of these services across networks linking hospitals. They are reported ass “success stories”. For example, Manchester uses an integrated hub-and-spoke model that provides one comprehensive, two primary and six district stroke centres. Results include increasing the number of eligible patients receiving thrombolysis within the metropolitan area from 10 to 69 between 2006 and 2009.

The decision over the future of services in Staffordshire allows to put to the test the idea that health care teams can develop a relationship over time with a ‘registered’ population or local community. They can therefore target individuals who would most benefit from a more co-ordinated approach to the management of their care. For example, a “frail elderly assessment service” might well to act as a one-stop assessment for older people and take referrals from a wide range of sources to better meet the needs of the frail elderly. The ‘new look’ services in Mid Staffs could become a ‘test bed’ for seeing how information technology (IT) could be best used. IT could, in this way, support the delivery of integrated care, especially via the electronic medical record and the use of clinical decision support systems, and through the ability to identify and target ‘at risk’ patients

A clinician–management partnership that links the clinical skills of health care professionals with the organisational skills of executives, sometimes bringing together the skills of purchasers and providers ‘under one roof’, might become more likely in future. This might be particularly important for ensuring that patient safety targets are actually met in clinical governance, and corrective action can be initiated if at any stage deemed necessary. The engagement of actual patients would be very much in keeping with Berwick’s open organisational learning culture. Of course the Care Bill cannot set top-down commands for organisational culture and leadership. It was interesting though that these were discussed in yesterday’s debate. Effective leadership at all levels will be necessary to focus on continuous quality improvement. A collaborative culture will be needed which emphasises team working and the delivery of highly co-ordinated and patient-centred care.

So the future of Mid Staffs clearly represents an opportunity for the NHS, not a threat; it would be helpful if politicians of all sides could rise to the occasion with maturity and goodwill.

This is no time for an amateur. Burnham must become Secretary of State for Health.

Andy Burnham MP (@andyburnhammp), Shadow Secretary of State for Health, was interviewed this morning by veteran broadcaster, Andrew Neil (@afneil) on #BBCSP.

The question is how well the NHS is prepared for the winter period this time around. This is no time for an amateur. Winter staffing levels and bed capacity are going to be vital planning considerations.

According to Richard Vautrey (Deputy Chair of the BMA GPs committee), “Doctors and all healthcare professionals are hugely frustrated… The political knockabout is hugely frustrating.”

Neil asked Burnham what one move he would implement to relieve the crisis in A&E forecast for this winter.

“I would immediately halt the closure of NHS walk-in centres”, announced Burnham.

There has been much criticism over the NHS 111 ‘rolled out’ by the Coalition, and indeed Keogh this week signalled that he wished to extend the powers of NHS 111 in the next few years in a reconfiguration of A&E services.

Burnham himself has much attacked how people are not clinically trained have to stick to their algorithms, which invariably end with ‘Go to A&E!’ for difficult problems.

“I would put nurses back on the end of phones, and restore the NHS Direct-type service”.

Of course, many people in English health policy feel that the A&E problem has been exacerbated with sometimes inappropriate ‘social admissions’. Burnham cites often that the ‘whole person’ was a founding principle of the National Health Service under Bevan. Therefore it was unsurprising that he should bring up this flagship policy of Labour in this brief interview.

“I want to rethink how the NHS works – the full integration of health and social care.”

Neil then went onto explore other interesting issues currently confronting English health policy.

Should the NHS brace itself for another ‘top down reorganisation’ under Labour after May 8th 2015?

“No it shouldn’t. I will repeal the Health and Social Care Act. Moving forward, it’s all about making the current structures do different things. I will work with the health professions.”

At this point in the interview, Andy Burnham started ‘talking back’ (politely).

“Why don’t you spend time talking about £1.5bn NHS reorganisation?”

GPs have been put in the firing line by Jeremy Hunt, especially the 2004 GP contract. Accessibility to GPs has therefore become a political ‘hot potato’.

Labour has been much criticised for the ‘target driven culture’. Indeed, the political manifestos in 2010 had appeared to signal a shift from this culture. Managers being driven by targets keep on resurfacing in the news headlines; as for example, the recent furore in Colchester.

This, however, was a positive opportunity to talk about a beneficial target which had been scrapped.

“We brought in evening and weekend opening. This has been reversed too.”

“I welcome a move to bring back named GPs. But I want to be clear. It’s got harder to get a GP appointment, as the 48 hour target – which we introduced – has been scrapped.”

The Health and Social Care Act (2012) is fundamentally hinged on a competitive market and its regulation.

It is clear now, however, that competition, heavily touted by some think-tanks, has become a massively flawed plank in policy.

Referring to David Nicholson’s recent evidence in the Health Select Committee, Burnham opined, “Only last week the CEO of the NHS is bogged down in a ‘morasse of competition law”.”

Furthermore Burnham signalled that he welcomed a right for patients to come under GPs outside of their catchment area, as he had indeed promised before the last election.

On the general issue of how GPs are performing, Burnham added quickly, “I think every political party supports transparency.”

This week is likely see a number of proposals from the current Government in response to the latest Francis report about Mid Staffs, which had really put patient safety in the NHS into the public spotlight.

“‘Wilful neglect’ was a recommendation of the Francis Report. You can’t ‘pick and mix’ the recommendations. It is an entire package. It must be implemented in full. This includes safe staffing levels. The Government has a responsibility to staff as well.”

Is the GPs Contract of 2004 to blame? ‘Our survey’ of Stephen Dorrell and Alan Milburn “say no”.

Milburn even called it ‘nonsense’, saying though he felt Jeremy Hunt’s “pain”.

“[The Contract] got changed every year from 2004. There are a lot of myths which have built up around the contract. The 2004 Contract was responsible for the A&E crisis is just spin of the worst kind.”

Then veteran broadcaster Neil started talking about other issues.

“I can’t believe you’re talking about those emails on a national programme. You’re really scraping the barrel.”

They both chuckled and ended the brief interview.

This is no time for an amateur.

He may drive the Tories “nuts”, but yesterday was a virtuoso interview from Burnham.

Andy Burnham MP must become the Secretary State of Health.

Explicit acknowledgement from the Court of Appeal that the government is taking the TSA model to attempt widespread NHS reconfiguration

The judgment from the appeal court (Court of Appeal), the second highest court in England and Wales, provides useful clarification on the reasoning behind why Jeremy Hunt lost.

This judgment has been published thus by LJ Sullivan, with their other Lordships in agreement, including significantly the current Master of the Rolls.

Jos Bell explains elegantly the situation regarding Lewisham on the ‘Our NHS’ website as follows:

In the Lewisham case, the judge, Justice Silber, had ruled that Hunt and his administrator Matthew Kershaw had no right to use the ‘special administration process’ in a neighbouring NHS trust – South London – to meddle in the affairs of unrelated Lewisham Hospital – and to ignore the view of local GPs.

In part, this sudden pop-up Amendment (to Care Bill Clause 109) is the action of a government shoring themselves up for a judicial defeat. Lewisham campaigners suspect that the government senses their Appeal, due to be heard just a week after the Lords debate has been tabled, is on rocky ground. Although the Amendment will not apply retrospectively to the Lewisham case, if it passes it would enable them to rain blows on Lewisham that they have been unable to inflict by other means, all over again.

It is reported that the health minister Frederick Howe had explained in a letter to peers that the amendment would “put beyond doubt” that the trust special administrator has power to make recommendations and that the health secretary (or Monitor in the case of foundation trusts) has the power to take decisions that affect providers other than the one to which the administrator was appointed.

The Court of Appeal decision fundamentally hinges on a very strict point of law – that is, what parliament had intended, particularly in relation to how Chapter 5A must be construed in the context of the 2006 Act as a whole [as legislated].

Due to the separation of powers in English law, it is not for judges to make the law generally.

Judges are there to interpret the law.

The Court of Appeal appears to be acknowledging that the current government is taking the TSA model to attempt widespread NHS reconfiguration. The evidence for this strikingly emerged in para. 19 of the Judgment:

- The fact that in some cases a TSA might think it necessary to go further and make recommendations for action in relation to other Trusts, as happened in the present case, might be a justification for conferring wider powers on TSAs and the Secretary of State, but whether or not that would be desirable is a matter for Parliament, not this Court. We were told that a new clause has been inserted into the Care Bill, which is presently before Parliament. The new clause provides that references in Chapter 5A to taking action in relation to an NHS trust include a reference to taking action “in relation to another NHS Trust”. This is precisely the kind of provision that one would have expected to see in Chapter 5A if Parliament had intended it to have the meaning attributed to it by the Appellants.

Now it is crucial for Parliament to decide how it is going to progress on this issue.

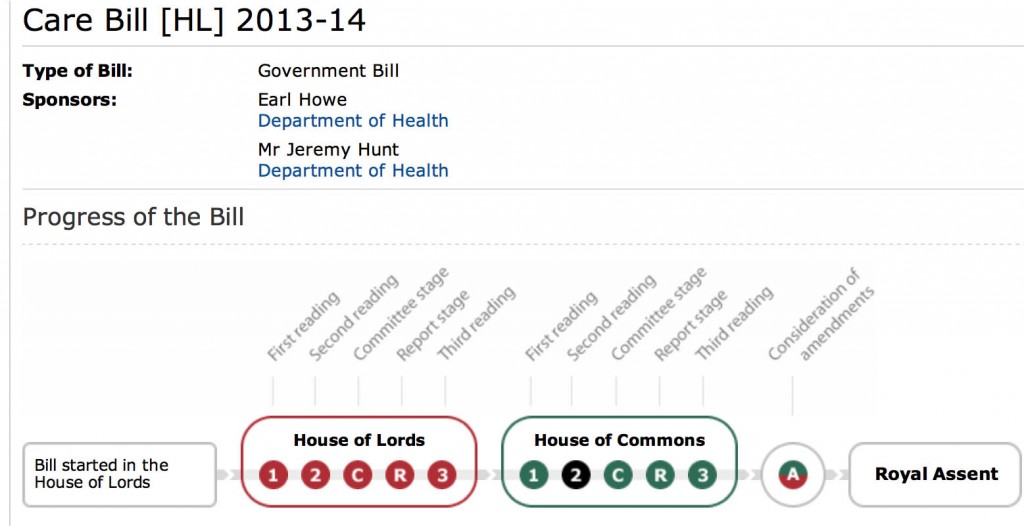

It is also vital to acknowledge that the Care Bill 2013 has not obtained Royal Assent yet.

It’s not law yet.

But it is getting closer and closer.

As confirmed by Jos Bell, the next steps are going to be crucial.

The law has to be “clear, unambigious and devoid of relevant qualification“.

Judges in deciding upon controversial cases often have to go behind ‘what parliament had intended’.

But what parliament had intended was clear.

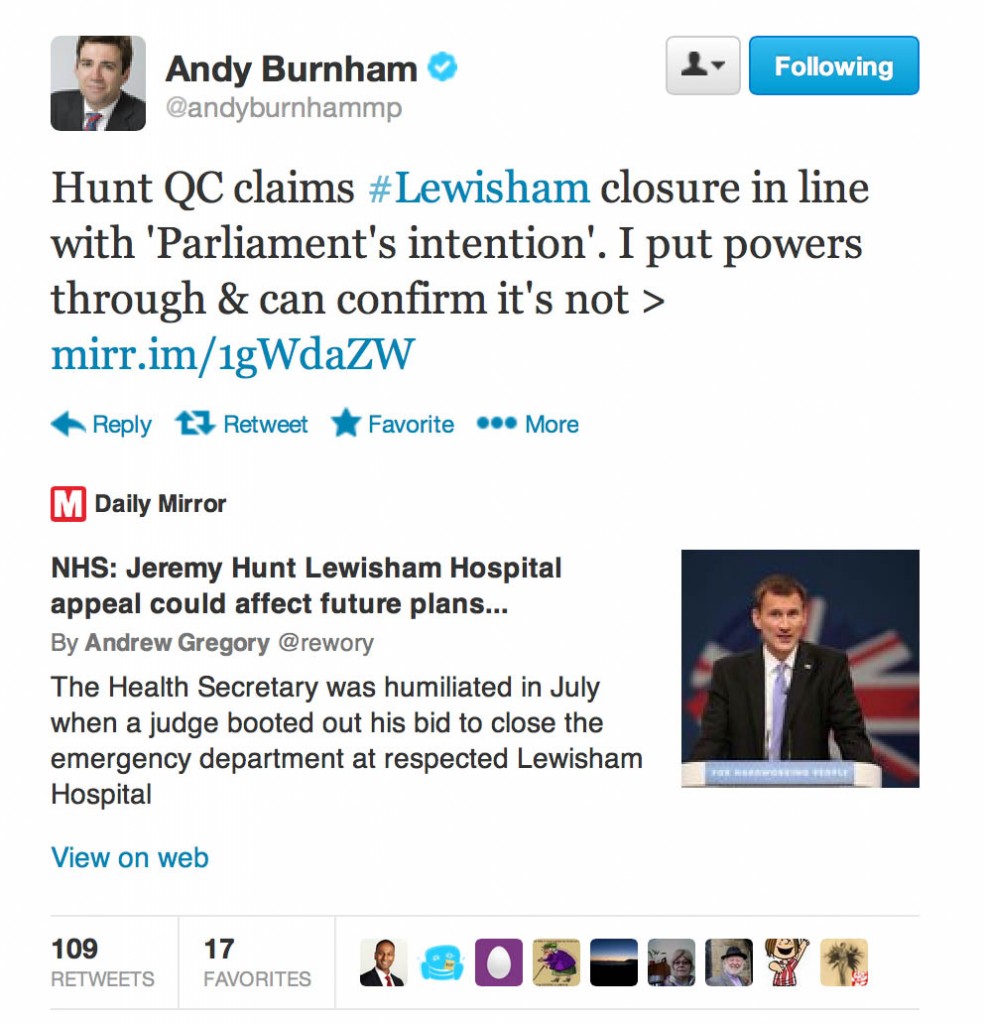

Lawyers are indeed allowed to look to external statutory aids to help them interpret the law. This can conceivably even in come in the form of Twitter. Andy Burnham MP, the former Secretary of State for Health, announced on Twitter on 28 October 2013:

Jeremy Hunt’s cardinal mistake for both the High Court and the Court of Appeal was try to act outside of his powers. What the current executive is attempting here is an aggressive use of the ‘special administration process’ to shut down NHS entities, contrary to p.47 of the 2010 Conservative Party Manifesto.

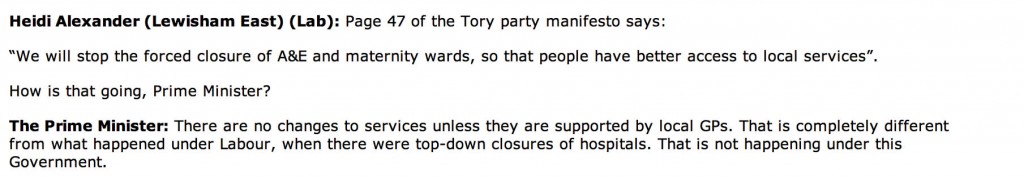

That the Conservative Party had broken their Manifesto pledge was articulately demonstrated in #pmqs by Heidi Alexander MP this week (as reported in Hansard):

The Coalition is propelling us at high speed into the chaotic “dog-eats-dog” ‘rule of the market’. It is this out-of-control market which appears fundamentally, and rather paradoxically, anarchic.

For Labour currently, it is critical that abuse of powers through the TSA ‘route’ is stopped.

It is widely anticipated that Liz Kendall MP and Jamie Reed MP will be playing a critical rôle in Labour’s response to the Care Bill including its amendments. One cannot wish but to give them full support, as this parliamentary fight is not over by any means.

In a significant step, Jeremy Taylor, Chief Executive of “National Voices” has asked for the Department of Health to withdraw this amendment to the Care Bill. He has copied in fact his letter to Norman Lamb MP and Una O’Brien.

Jeremy’s letter could not be clearer:

We recognise the special and difficult circumstances surrounding trust failure. We do not accept that these conditions justify cutting out patient and public involvement. If anything it is the reverse. Without the input of the citizens affected by the changes, decisions taken in haste are more likely to be wrong and more likely to erode public confidence. The circumstances call for a different model of engagement, not an absence of engagement. National Voices, together with our members, partners and friends, offers to work with the Department and other key system players to help co-produce such a model.

A clear solution for what (now) ‘parliament intends’, especially given that no party won the general election of 2010, is not in sight yet.

You can’t trust David Cameron with the NHS

This afternoon at just after midday, David Cameron clashed with Ed Miliband over the impending A&E crisis.

The Labour Party have issued a broadcast as follows:

One of the exchanges was particularly revealing – also in demonstrating that David Cameron doesn’t know the brief well of an important contemporary issue in English health policy.

The exchange has been reported in Hansard today as follows:

Edward Miliband:The Prime Minister is giving P45s to nurses and six-figure payoffs to managers. Can he tell us how many of the people who have been let go from the NHS have been fired, paid off and then re-hired?

The Prime Minister:First, we are saving £4.5 billion by reducing the number of managers in our NHS. For the first time, anyone re-employed has to pay back part of the money they were given. That never happened under Labour. We do not have to remember Labour’s past record, because we can look at its record in Wales, where it has been running the health service. It cut the budget by 8.5%, it has not met a cancer target since 2008, and it has not met an A and E target since 2009. The fact is that the right hon. Gentleman is too weak to stand up to the poor management of the NHS in Wales, just as he is too weak to sack his shadow Health Secretary.

Edward Miliband:And we have a Prime Minister too clueless to know the facts about the NHS. Let us give him the answer, shall we? The answer is that over 2,000 people have been made redundant—[Interruption.] The hon. Gentleman says it is rubbish; it is absolutely true—we have a parliamentary answer from one of the Health Ministers. Two thousand people have been made redundant and re-hired, diverting money from the front line as this Prime Minister sacks nurses. [Interruption.] The Prime Minister seems to be saying it is untrue; well, if he replies he can tell me whether it is untrue. We know why the NHS is failing: his botched reorganisation, the abolition of NHS Direct, cuts to social care, and 6,000 fewer nurses. There is only one person responsible for the A and E crisis, and that is him.

Unknown to Cameron, @andyburnhammp had asked exactly the same question as @Ed_Miliband asked in #pmqs and got a reply.

The reference for this Q/A is: http://bit.ly/1ejPr3Q

Andy Burnham: To ask the Secretary of State for Health how many NHS staff have been made redundant and subsequently re-employed by NHS organisations on a (a) permanent basis and (b) fixed-term contract basis since May 2010. [147768]

Dr Poulter: The number of NHS staff made redundant in the NHS since 1 May 2010 and subsequently re-employed by NHS organisations on a (a) permanent basis is estimated to be 1,300 and (b) fixed-term contract basis is estimated to be 900.

These estimates are based on staff recorded on the Electronic Staff Record (ESR) Data Warehouse as having a reason for leaving as either voluntary or compulsory redundancy between 1 May 2010 and 30 September 2012, and who have a subsequent record on the ESR Data Warehouse up to 30 November 2012.

In April 2010 there were 42,515 full-time equivalent (FTE) managers. Between April 2010 and November 2012 this figure has reduced by 6,905 to 35,610 FTE.

The ESR Data Warehouse is a monthly snapshot of the live ESR system. This is the HR and payroll system that covers all NHS employees other than those working in General Practice, Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and Chesterfield Royal Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, and some NHS staff who have transferred to local authorities and social enterprises.

Thanks to @DrEoinCl for finding this.

On the sensitive issue of how many people who had been made redundant were later appointed by the NHS, which David Nicholson was asked about yesterday, David Cameron attempted a bluster with no real avail.

Matthew d’Ancona on the formation of the Coalition: they were the future once

The Coalition were the future once.

Matthew d’Ancona, a pretty formidable intellect himself, has been publicising his excellent book, “In it together – the inside story of the Coalition.” Britain actually had had no recent experience of coalition government, so this work of scholarship is a very useful one. d’Ancona found that it wasn’t the fevered days following the Coalition which determined most the coalition. d’Ancona felt, however, that behind the scenes of their election campaign, it was known that the Conservatives knew that they couldn’t win the 2010 general election (for a period of months before the election.) At the time, David Cameron was producing a ‘moderate’ offering, and the Orange Bookers were dominating the Liberal Democrat Party.

d’Ancona feels that it was possible to draw together common strands from the Conservative and Liberal Democrat manifestos. It was very difficult to forge together the parties, despite commonalities in approaches from their grassroots memberships. Having the Liberal Democrats inside the Coalition was seen as a useful way of ‘taming the Tory right’, such as Peter Bone MP and Bill Cash MP, and it turns out that the major impetus for the fixed term Government was from the Conservatives who felt the Liberal Democrats might have bailed out.

It’s said that the coalition government is run by the ‘quad’ – David Cameron, Osborne, Nick Clegg and Danny Alexander. Osborne invariably chairs this meeting of the most senior officials and advisers because of his political skills. The expertise regarding the NHS is pretty small. In fact, the expertise in the current Coalition leadership is pretty poor. In comparison, the expertise of an incoming Miliband government will be quite great in comparison. d’Ancona has usefully likened it to a traditional ‘oligarchy’ – to be contrasted with the “sofa government” characterised by Tony Blair’s approach. Blair himself had had very little experience himself of senior offices of state prior to being Prime Minister.

Boris Johnson is alleged to have said that the formation of the Coalition was a ‘triumph of the public school system’. Indeed, it is reputed that George Osborne MP and David Cameron MP saw themselves as the antithesis of the dysfunctional Blair-Brown relationship. Clegg and Cameron had both come from a public school background, been through the Oxbridge mill, were at ease with modernity and “at ease with affluence” (according to d’Ancona). In keeping with this, Rafael Behr in the New Statesman comments:

D’Ancona describes a tight social circle running the Tory side of the coalition – old friends, their wives, ex-girlfriends, all joining each other for holidays and dinner parties and sharing childcare, now all ministers or Downing Street staffers. He draws the contrast with the New Labour elite who took charge of the country in 1997. Tony Blair’s clan started life as a political project and only later evolved into a governing family before splitting into mafiosi tribes. Cameron’s was a clique before it thought of running the country. That makes it more affable than the Blairites but also lacking in purpose. The Cameroons had an easy ride to power before they had thought enough about what power should be for.

The book by d’Ancona also comes warmly recommended by Nick Cohen, writing in the Guardian:

No journalist has better access to our rulers than Matthew d’Ancona. As a liberal conservative, he is at ease with the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, and it is at ease with him. Just about everyone in power spoke to him for In It Together, and as a result, I doubt there will be a better insider’s account of the coalition for years. If you want to understand today’s high politics, you should read him.

Ideally, one should check progress against the Coalition Agreement which is in a non-legal sense a compromise agreement of its own. Even that agreement is fraught with blind alleys, notions such as ‘we will give enhanced powers to the PCTs’ and the such like. However, d’Ancona says that going through the two manifestos became a textual exercise, where they arguably saw areas of overlap. What we have therefore seen in the last three years represents this area of overlap. Indications are with an emphasis on patient safety, 24/7 and ‘out of hours’ care, no more maternity and A&E closures what was promised was very far from reality.

No more top down reorganisations?

The curious starting point of the Conservative manifesto is that David Cameron and his party wish to protect the NHS from top-down reorganisations. This is blatantly a lie as anyone who has read ‘NHS SOS’ will clearly conclude.

“more than three years ago, David Cameron spelled out his priorities in three letters – NHS. Since then, we have consistently fought to protect the values the NHS stands for and have campaigned to defend the NHS from Labour’s cuts and reorganisations. as the party of the NHS, we will never change the idea at its heart – that healthcare in this country is free at the point of use and available to everyone based on need, not ability to pay.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

Only this afternoon, Dr Sarah Wollaston MP was asking the current NHS England CEO, Mr David Nicholson, about whether the English law was a ‘barrier to reconfiguration’. Of course, the essential issue is NOT whether the law is OBSTRUCTIVE to the NHS carrying out reconfigurations. Reconfigurations must be led by proposed benefits or improved outcomes in quality of care locally, at a clinical level, and should not be merely seen as a cost-cutting exercise to deliver the £20bn or so McKinsey ‘efficiency savings’. The Conservative Party manifesto therefore takes the position of MPs wishing to save their seats in such reconfigurations, rather than the national stance it later adopted over Trust services. The Lewisham campaign has recently won a second victory at the Court of Appeal, and the decisions of the Trust Special Administrator (TSA) in Staffordshire have yet to be published.

“We will stop the forced closure of A&E and maternity wards, so that people have better access to local services, and give mothers a real choice over where to have their baby, with nhS funding following their decisions.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

And this even appears to be an area of agreement between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. However, in the drive for the NHS ‘efficiency savings’, as part of the austerity aka ‘cuts’ national interest narrative, this could have been a firm commitment for this Government. Most people agree that this Government has conducted backdoor reconfigurations of the NHS in a cack-handed manner, though it is unclear precisely what Labour wish to legislate regarding this, currently?

“The NHS often feels too remote and complex. Local services – especially maternity wards and accident and emergency departments – keep being closed, even though local people desperately want them to stay open.”

Liberal Democrat Manifesto 2010

And the creation of NHS England is at least signposted in the Conservative Party manifesto.

“We will make sure that funding decisions are made on the basis of need, and commissioning decisions according to evidence-based quality standards, by creating an independent NHS board to allocate resources and provide commissioning guidelines.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

This – at first blush – seems contradictory to the Liberal Democrat version, although the LibDems also concede a need to stem management costs. The creation of NHS England might conceivably be considered an area of commonality between the two parties, depending on your perspective.

“We have identified specific savings that can be made in management costs, bureaucracy and quangos, and we will reinvest that money back into the health care you need.”

Liberal Democrat Manifesto 2010

The ensuing ‘Coalition agreement: A programme for government‘ makes numerous references to PCTs, which were also ultimately scrapped in the NHS ‘reforms’.

However, at least the Liberal Democrats do throw forward to the concept of abolishing PCTs. It might be argued that the Liberal Democrats at this stage were still living in ‘cloud cuckoo’ land, with making all sorts of pledges and promises believing that they would never come into government (as per the tuition fees debacle.) And yet it is the Coalition government that implemented the Health and Social Bill as it was going through parliament, and beyond after it obtained Royal Assent. Had the Liberal Democrats been at all serious about government, irrespective of whether the general public took them seriously or not, they should have attempted to budget the opportunity cost of dismissals and subsequent re-appointment elsewhere in the system.

David Nicholson, current NHS England chief, explained today that he does not have this information about dismissals leading to reengagement, although he claims to have the figure for redundancies etc. overall. This is something which the Conservative government, and presumably David Baumann, the Chief Financing Officer, could have budgeted for. Of course, the current Government prides itself on fiscal responsibility, having never clearly stated as to whether they too would have bailed out the investment banks to the tune of £860bn thus massively increasing the deficit.

The Liberal Democrats’ plan to scrap PCTs is clearly stated here:

“Empowering local communities to improve health services through elected Local Health Boards, which will take over the role of Primary Care Trust boards in commissioning care for local people, working in co-operation with local councils. Over time, Local Health Boards should be able to take on greater responsibility for revenue and resources to allow local people to fund local services which need extra money.”

Liberal Democrat Manifesto 2010

Resource allocation problems

There have been thousands of nursing staff cut under the Conservative-led government, with parts of the capital relatively shielded from the effects of the cuts.

“We all know that too much precious NHS money is wasted on bureaucracy, and doctors and nurses spend too much time trying to meet government targets.”

Liberal Democrat Manifesto 2010

The ‘pledge’ made by the Conservatives for allocating resources in the NHS responsibly is of course hugely laughable, with the benefit of hindsight of a reorganisation estimated at £2.4 bn.

“as a result, we will be able to cut the cost of NHS administration by a third and transfer resources to support doctors and nurses on the frontline.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

John Appleby from the King’s Fund in the lifetime of this Coalition government has written in the BMJ on how the issue of ‘increased health spending’ has been mischievously addressed thus far.

“We will back the NHS. We will increase health spending every year. We will give patients more choice and free health professionals from the tangle of politically-motivated targets that get in the way of providing the best care.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

Jeremy Hunt has indeed announced to limit the pay and bonuses of NHS managers, indeed referring also to how such pay shouldn’t exceed that of the Prime Minister announced in the Liberal Democrat manifesto. The problem with this argument is that it is alleged that Jeremy Hunt’s personal income for various reasons is quite large, compared to the income of the nurses he is currently sacking.

“We will cut the size of the Department of Health by half, abolish unnecessary quangos such as Connecting for Health and cut the budgets of the rest, scrap Strategic Health Authorities and seek to limit the pay and bonuses of top NHS managers so that none are paid more than the Prime Minister.”

Liberal Democrat Manifesto 2010

Health and Social Care Act (2012)

The Health and Social Care Act (2010) created the largest QUANGO in the universe, some allege, though commissioning power has been devolved locally to clinical commissioning groups (CCGs). However, it is still a moot point whether CCGs are genuinely clinically-led.

As CCGs are state insurance schemes, there’s actually no obligation for them to have much clinical input, so that they can ascertain the pooling of risk competently. No formal stipulation has ever been given on the optimal size of the CCG, interestingly.

Possibly the most significant line however is the comment that the NHS puts ‘targets before patients’. Whilst it is claimed that the targets introduced by the Labour administration improved patient care, e.g. waiting times, only this evening we had yet another report of performance figures being gamed by a English NHS Trust (Colchester).

“We have a reform plan to make the changes the NHS needs. We will decentralise power, so that patients have a real choice. We will make doctors and nurses accountable to patients, not to endless layers of bureaucracy and management. We can’t go on with an NHS that puts targets before patients.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

The Health and Social Care Act (2012) does, however, have three primary aims of legislation, despite the enormous volume of it at 493 pages.

The primary aim of it is to pivot the NHS on price competitive tendering. This was of course the famous section 75 which we all warned about. I was one of the first people to warn about the cost about this for resource allocation, in fact, in an article on this blog at the beginning of January 2013. David Nicholson, in contrast, appears to have been totally oblivious to the costs we had all warned him about, in his evidence to the Health Select Committee this afternoon. I wonder if he is fully aware of the extent of the failure of this showpiece plank in this policy, as I wrote about on this blog recently too.

The second arm of the legislation is a redefinition of the failure regime. This clearly has not gone according to plan from the Coalition’s point of view, with the present Government having hurriedly legislated for an amendment in the Care Bill (2013) to extend the powers of the TSA, as described here.

The third arm of the legislation is to put in place the regulator for this competitive market, Monitor. This has necessarily meant re-allocation of scarce resources away from frontline care into the regulator’s processes. But even in 2010, the Conservative Party gave a clear warning shot that they wished to extend the scope of the NHS market. Online reports of the performance of healthcare providers, in promoting ‘customer choice’, are in fact mentioned in the second set of regulations for section 75 (the revised statutory instrument – No 500 – after the first one – No 257 – had to be discarded due to popular criticism.)

“We need to allow patients to choose the best care available, giving healthcare providers the incentives they need to drive up quality. So we will give every patient the power to choose any healthcare provider that meets NHS standards, within NHS prices. We will publish detailed data about the performance of healthcare providers online.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

“We will set NHS providers free to innovate by ensuring that they become autonomous foundation trusts.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

The drive towards integration became particularly apparent when the first set of section 75 NHS regulations had to be scrapped, with Norman Lamb ferreting around for a compromise which Baroness Williams and partners-in-crime could sell to their Lordships.

It is hard to when at what stage the Liberal Democrats will begin their process of ‘differentiation’ from their partners, the Conservative Party, in the coalition, as described famously by LibDem strategist Richard Reeves. With the introduction of Norman Baker at the Home Office, it is conceivable that the Liberal Democrat Party will wish to make its mark on policy sooner rather than later.

The problem with integrated bundles is that it has just kicked the competition law football down the line, and this will have to be picked up again by Andy Burnham MP in the latest incarnation of integrated shared care packages, “whole person care”.

Integrated packages, especially if delivered through the ‘prime contractor model‘ where legal liability is currently unclear, may offend competition law in this jurisdiction.

The danger for Burnham of course is that by picking up the ball he might create a foul under the rules of football, unless he suddenly changes the rules to rugby; or, in political terms, changes the narrative to whole person care, which a sovereign parliament has legislated for.

“Integrate health and social care to create a seamless service, ending bureaucratic barriers and saving money to allow people to stay in their homes for longer rather than going into hospital or long-term residential care.”

Liberal Democrat Manifesto 2010

Personal budgets

The Conservative Party (just) have been marginally more open about personal budgets for social care. However, I have previously argued in my ‘OurNHS’ article called “Shop til you drop“, that this is a narrative that has gone on relatively unnoticed from all parties, and is likely to be an important policy issue in the near future in England, at least. This is set to become an explosive issue in the next parliament, with likely attempts to merge the healthcare and social care budgets. If these budgets get merged with universal credit, thus far scuppered by a poor NHS IT infrastructure, amidst a drive towards NHS data sharing (see this article from Tim Kelsey from today), this is a policy area which deserves special scrutiny.

“Where possible we want to devolve control over health budgets to the lowest possible level, so people have more control over their health needs. for people with a chronic illness or a long-term condition, we will provide access to a single budget that combines their health and social care funding, which they can tailor to their own needs.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

Public health

The Conservative-led government in the end rejected minimum pricing of alcohol and standard packaging of cigarettes.

I discussed some of the furore over standard packaging of cigarettes here, in relation to alleged “The Wizard of Oz effect” of Lynton Crosby.

A powerful criticism of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) was that it represented the end-point of powerful secret lobbying on behalf of the private healthcare provider corporates; and thus represented rent-seeking behaviour from the private sector in a pretty obvious ‘corporate capture’.

An interesting article on the phenomenon of corporate capture in public health in recent years was produced in the BMJ.

Nonetheless, the following bold, and now meaningless promises, are made in their manifestos.

“Reduce the ill health and crime caused by excessive drinking. We support a ban on below-cost selling, and are in favour of the principle of minimum pricing, subject to detailed work to establish how it could be used in tackling problems of irresponsible drinking. We will also review the complex, ill-thought-through system of taxation for alcohol to ensure it tackles binge drinking without unfairly penalising responsible drinkers, pubs and important local industries.

Liberal Democrat Manifesto 2010

“We will turn the Department of health into a Department for Public health so that the promotion of good health and prevention of illness get the attention they need. We will provide separate public health funding to local communities, which will be accountable for – and paid according to – how successful they are in improving their residents’ health.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

“Lifestyle-linked health problems like obesity and smoking, an ageing population, and the spread of infectious diseases are leading to soaring costs for the NHS. at the same time, the difference in male life expectancy between the richest and poorest areas in our country is now greater than during victorian times.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

Primary care

The future of general practice is a huge area, as I have previously given a brief account of.

‘Out of hours’ care has been a huge issue in the last few years. In April 2013, NHS England directors admitted that patients have been “let down” by the “unacceptable” failure of some NHS 111 services.

Prof Clare Gerada is about to step down as Chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners. She gave a brief account of what had to be done about out-of-hours care in her wide-ranging speech for the RCGP in October 2013:

Further details, published in the Guardian, are here.

The idea that GPs are directly involved in providing out-of-hours care was dealt a heavy blow in 2012 when it was reported that the Harmoni out-of-hours service was ‘putting patients at risk’.

“Ensuring that local GPs are directly involved in providing out-of-hours care.”

Liberal Democrat Manifesto 2010

And in June 2013, it was described that ‘out of hours, out of GPs’ hands‘.

The “24/7 narrative” has nonetheless continued, and I have blogged on the feasibility of this here quite recently.

“People want an NHS that is easy to access at any time of day or night. We will commission a 24/7 urgent care service in every area of england, including GP out of hours services, and ensure that every patient can access a GP in their area between 8am and 8pm, seven days a week.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

And, finally, it’s no particular surprise that the issue of GP records ending up in a national state information database, with flimsy valid consent if at all, did not appear in either manifesto.

Patient safety

It is impossible not to be affected by the sheer horror of Mid Staffs (I have previously blogged on toxic cultures), though it is important to acknowledge that staff in the Staffordshire area have been successful, it is argued, at turning this organisation around in recent times.

It is a significant tragedy of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) that there is not a single clause on patient safety, save for one clause on the abolition of the National Patient Safety Agency.

“We all need to be assured that, if we become unwell, the care we get will be of good quality. Most of all, we need to be confident that our safety comes first, and that the treatment we get doesn’t put us in more danger. We will introduce a series of reforms to improve patient safety.”

Liberal Democrat Manifesto 2010

The Government has been slow to legislate for a ‘duty of candour’, after the Francis reports, save for an amendment in the Care Bill (2013).

“We will require hospitals to be open about mistakes, and always tell patients if something has gone wrong.”

Liberal Democrat Manifesto 2010

Prof Sir Mike Richards has been appointed as a new Chief Inspector of Hospitals, Prof Steve Field has been appointed as Chief Inspector of General Practice, and Andrea Sutcliffe has been appointed as Chief Inspector of Social Care.

There is still a concern that the provision of social care will be through ultimately a mandatory insurance system. There is also a concern that this discussion will not be laid out openly by any political party ahead of the May 7th 2015 general election.

Conspiracy theorists have held that ultimately integration of healthcare and social care, if enabled through a competent national IT system, will ultimately lead to integration of personal healthcare and social budgets; and even possibly with the private insurance system.

The ‘data farms’, which Tim Kelsey speaks about, could also be a source of entities denying healthcare, social care or benefits from entities in the public or private sector, in future, if not adequately regulated.

“We reject Labour’s plans for a compulsory ‘death tax’ on everyone to pay for social care, regardless of their needs. We want to create a system which is based on choice and which rewards the hundreds of thousands of people who care for an elderly relative full-time. So we will allow anyone to protect their home from being sold to fund residential care costs by paying a one-off insurance premium that is entirely voluntary. Independent experts suggest this should cost around £8,000. We will support older people to live independently at home and have access to the personal care they need. We will work to design a system where people can top up their premium – also voluntarily – to cover the costs of receiving care in their own home.”

Conservative Party Manifesto 2010

Where now?

And so in the words of Shirley Bassey history is repeating itself…

The Conservative Party know that they will need a miracle to win the 2015 general election on May 7th 2015, with Nick Clegg having delivered a fatal blow through the lack of boundary changes, perhaps in retaliation for AV.

The 493 page Health and Social Care Act (2012) did not deliver a single clause on patient safety.

And yet there is unfinished business there, with a possible statutory duty of candour for organisations and individuals; and a strengthening of the law on wilful neglect building on the Mental Capacity Act.

Whistleblowing against unsafe cultures is also a fertile area for legislating anew. I have previously argued that the Public Interest Disclosure Act is not currently fit-for-purpose. I have also emphasised that it may not be possible to legislate on everything to do with culture, but we should try to advance a culture which promotes ‘speaking out safely‘. It may also be necessary to revisit the issue of ‘safe staffing‘ soon.

Burnham intends to introduce the ‘NHS preferred provider’ approach, but this still perpetuates the market. It could still run into trouble if the US-EU free trade agreement comes in on the sly (I mentioned it here previously). Now that this government has firmly nailed its colours to the EU competition law mast, some drastic action is going to have to be taken by Burnham and Labour in repealing the Health and Social Care Act (2012). It is also critical that Part 3 of the said Act is reversed, so that not all the ongoings of the NHS are seen in the prism of the EU ‘economic activity’ prism, or else mergers proposed on the basis of clinical decision-making but blocked on the basis of legal competition law considerations will continue to be blocked.

Finally, no party wishes to mention PFI in its manifestos at all, although the policy think-tank behind this can be traced very accurately to the Major government as I explained here. Labour’s relative silence on this is troubling, not least because it gives uncertainty about the future of the NHS and what to do about ‘failing hospitals’. Labour does need to clarify the law on this in some way, if it disagrees with extending the powers of the TSA.

Labour claims to aspire for a comprehensive, free-at-the-point-of-need service, and, if it wishes to do this, if it believes in billions of efficiency savings and if it believes in a need for reconfigurations, it may well need to go further than simply aspiring to repeal the Act.

The strange thing is that Andrew Adonis’ version, “Five days in May: the Coalition and beyond“, paints a rather different picture, which emphasises more the commonalities in policy between Labour and the Conservatives.

If the general election of May 2015 delivers a ‘hung parliament’ comprising Labour and the Liberal Democrats, the person the Liberal Democrats wish to work with Ed Miliband is going to be critical for determining the outcome of a second coalition, if Matthew d’Ancona’s observations are correct.

What Labour writes in its manifesto is therefore going to be analysed in great detail – especially the bits about the market, gaming the system, and patient safety I should imagine.

The future of general practice in England

One of the most striking aspects of the biggest reorganisation in the history of the NHS in recent years, estimated to cost about £3bn, is that it manifests glaring gaps in legislation. There is not a single clause on patient safety, save for abolishing the National Patient Safety Agency. It also does not discuss general practitioners themselves. It does contain a nice legislative framework however for the law anticipated for scenarios (sic) quite close to asset stripping, in the event that NHS Trusts have to be wound up due to insufficient funds.

I took a relative to have her ear syringed this morning in a local general practice, and I was thinking only this morning how general practice would be likely to have a backdoor reconfiguration in the next parliament whoever is in power.

I personally am fed up of even hearing about, let alone discussing, the “Tony Blair Dictum”. I prefer to think of it now as “The Deceptive London Cab Analogy“. The Dictum in its various manifestations states that it doesn’t matter who provides my NHS services, as long as it’s of good quality and free at the point of use et cetera. I have always found the idea of private providers freeloading on the goodwill and reputation of the NHS as odd, when presumably they wish to establish the quality and kudos of their own distinctive services. I think the “Deceptive London Cab Analogy”, in that I don’t particularly care if it is actually a London cab, as long as it looks like a London Cab, and gets me from A to B (for example the Royal College of Surgeons in Lincoln’s Inn Fields to the Royal College of Physicians in St Andrew’s Place). It’s a bonus actually if it costs me less. I don’t care how it gets me there; in effect, there’s no difference between using a SatNav or somebody who has done 4 years of “The Knowledge” and has been examined accordingly.

I personally am fed up of even hearing about, let alone discussing, the “Tony Blair Dictum”. I prefer to think of it now as “The Deceptive London Cab Analogy“. The Dictum in its various manifestations states that it doesn’t matter who provides my NHS services, as long as it’s of good quality and free at the point of use et cetera. I have always found the idea of private providers freeloading on the goodwill and reputation of the NHS as odd, when presumably they wish to establish the quality and kudos of their own distinctive services. I think the “Deceptive London Cab Analogy”, in that I don’t particularly care if it is actually a London cab, as long as it looks like a London Cab, and gets me from A to B (for example the Royal College of Surgeons in Lincoln’s Inn Fields to the Royal College of Physicians in St Andrew’s Place). It’s a bonus actually if it costs me less. I don’t care how it gets me there; in effect, there’s no difference between using a SatNav or somebody who has done 4 years of “The Knowledge” and has been examined accordingly.

Primary care is of course “the elephant” in the room, in that everyone knows that certain multi-nationals, assisted by liberalisation of international free trade, are licking their lips. It’s yet another one of those unmentioned topics in policy, like the NHS McKinsey efficiency or productivity savings, co-payments or personal health budgets. The whole world knows the existence of policy forks in the world, except none of the established traditional parties wish to discuss precisely the details. And people within thinktanks can continue to spin their motherhood and apple pie, in the hope that they can curry favour with an incoming administration. But it’s important for us who have other views on this to make such views known clear, otherwise a political party, including Labour, could legislate through the backdoor based on conversations also done behind-the-scenes. The public, whilst fed up about this ‘democratic deficit‘, are relatively powerless over it.

In 2010, Apax Partners published a revealing document entitled, “Opportunities: Post Global Healthcare Reforms“. The Apax Partners Global Healthcare Conference, which took place in New York in October 2010, sought opinions about the future of healthcare from some interested stakeholders. The ideology of the document is clear:

“With over 1.3 million employees, the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) is the world’s fourth largest employer and one of the most monolithic state providers of healthcare services.”

It is the ultimate nirvana for a businessman to find a new market. And general practice is articulated in those terms in the Apax document:

“The other change that (Mark) Britnell sees in the UK is even more fundamental: “In future, The NHS will be a state insurance provider not a state deliverer.”

Mark Britnell has been previously mooted as a possible contender for the replacement of Sir David Nicholson in the Health Services Journal.

The main problem about the current NHS top-down reorganisation is that it is important to identify the correct problem before producing an appropriate solution. If the problem which the Government wished to address was how to outsource and increase the number of private providers in the NHS, the solution, if implemented successfully, can be considered to be appropriate. When McKinsey sneezes, English health policy catches a cold. In this regard, McKinsey’s document, entitled “Five strategies for improving primary care” (“Report”; to download, please follow this link) provides some useful pointers. Affirming the importance of this market, the authors (Elisabeth Hansson and Sorcha McKenna) begin with the statement, “Primary care is pivotal to any health system.” Indeed, the first identified problem is that ‘in many countries, patients are dissatisfied with their ability to see GPs in a timely fashion.’ This is of course a problem which the operations management of any State-run service can address too. It is reported that, in Sweden, for example, many patients report that they cannot get timely access to their GP, especially by telephone. This is conceivably something which patient groups or the Royal College of General Practitioners could collect data on (and there is no shortage of data collection in primary care in the name of QOF) to improve the quality of the service.

It is mooted that, “the productivity of British GPs, for example, has dropped sharply in the past 15 years despite the fact that the government has markedly increased what it pays them“, on page 71, but this will be strongly contested by British GPs one assumes. The Report specifically discusses QOF thus:

“The United Kingdom has attempted to improve the quality of its primary care services through a new program, the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), which gives GPs additional payments if they meet specified outcome metrics (for instance, the percentage of hypertensive patients whose blood pressure is lowered to the normal range). The program has been successful in focusing attention and improving scores on those metrics, but it has become clear that a GP’s performance on those metrics does not always reflect the overall quality of his or her practice.”

There has been, particularly since Kenneth Clarke’s “The Health of the Nation” paper in the 1980s, an enthusiasm for GPs to be paid to collect data, but such data has to be meaningful.

Consistent with the Health and Social Care Act (2012), and the pivotal section 75 which acted as the rocket boosters for introducing competitive tendering formally into the English NHS, the document argues that:

“In both tax-based and insurance-based systems, competition is a way to increase GP productivity and the quality of care, because it signals to physicians that they will have to perform better if they want to retain their contracts and patients.”

This has only this week been powerfully rebutted by Professor Amanda Howe (MA Med MD FRCGP), Honorary Secretary of Council the Royal College of General Practitioners, in her response to Monitor as a member of Council (as linked here):

“The RCGP welcomes Monitor’s stated aim to better understand the challenges faced by general practice at a time when it is operating under increased pressure. However, we would strongly caution against the assumption that the challenges faced by general practice are caused by a lack of competition, or that the best lever to reduce perceived variability in access and/or quality would be an increase in competition.”

One of the most powerful levers described by the Report is “changing the operating model”.

“This lever is conceptually simple but often difficult to implement. For example, it often makes a great deal of sense to move physicians away from small (often solo) practices and into larger primary care practices or polyclinics (which include a wider variety of services, including diagnostics and outpatient clinics). Larger practices and polyclinics allow physicians to achieve economies of scale in some areas, such as administration. Furthermore, having a mix of physicians working together can improve quality and provide a more attractive working environment for new physicians (which might then help increase the workforce supply).

If a health system does decide to change its primary care operating model, it should consider a question even more radical than where physicians should work—it should ask whether certain primary care services need to be delivered by physicians at all. In the United States, for example, certain nurses with advanced training (nurse practitioners) are legally able to perform physical examinations, take patient histories, prescribe drugs, and administer many other basic treatments. Nurse practitioners can usually provide these services at a much lower rate than physicians typically can, but with comparable quality.”

This is a powerful summary, as it is consistent with the view that certain jobs can be better done by cheaper workforce. This is i itself a constructive idea potentially, simply in organising functions within the workforce for the people most suitable to deliver those functions. For example, many NHS hospitals have employed “physician assistants” to put in venflons or insert catheters, freeing up junior doctors to get on with other tasks in their busy schedule too. There comes a problem as to whether diagnostic services should be ‘liberalised’ on demand, i.e. so that the ‘worried well’ establishing their autonomy can pay to have their blood pressure checked ‘on demand’ if they want it. Provided that the equipment works, and the user of the diagnostic equipment does not use that equipment negligently, and that the investigation itself did not do any harm or damage, a regulator might not intervene, depending on the exact circumstances of course.

The second “big lever” is integration, described as follows:

“As we discussed earlier, GPs are typically responsible for coordinating with all the other health professionals and organizations (sic) that provide care for a patient. Coordination is hampered, however, by the fact that few health systems have effective methods for ensuring that information is transmitted to the appropriate places. Ensuring that such communication takes place does not require that all providers be part of a single organization (sic). However, it does require that all providers commit to sharing information and coordinating care and that a strong IT system operating on a joint platform is available to facilitate data exchange. Payors can encourage this type of alignment through their contracting (for instance, by requiring the providers to report the same set of metrics).”

And there is still a hangover of the integrated healthcare model from the US health maintenance organisations. Here it is possibly more of a case of joined-up thinking in some different ways. Regulators should be mindful of referrals being made between primary care and secondary care (where VerCo GP practice refers to Verco NHS Trust) not on the basis of clinical need but for shareholder dividend, though the cases of clinical regulators making sanctions on the basis of unethical conflicts of interest are currently sparse for whatever reasoning. It is also remarkable how keen and enthusiastic many corporates are on building the IT infrastructure for primary care, and indeed these noises of data sharing and paperless records are echoed by Jeremy Hunt. Ultimately, if one so wishes, whoever ‘owns’ primary care, whether it is a state-run service or not, this IT system could be ultimately linked to the private insurance system; a minority feel that that is where an aspect of integrated care is ultimately aiming towards.

The drumbeat from McKinsey’s and Apax is therefore providing a structural set-up and culture such that there can be a greater number of private providers in the holy grail of primary care. The notion that GPs are ‘only interested in their wallet’ (as famously said by Kenneth Clarke) is not at all borne out by the evidence from the professional bodies or regulators, and whilst there have been many touting GPs as businessmen (including some isolated opinions from the leadership of the Socialist Health Association (“SHA”) which have to be read in context, e.g. as in this recent blogpost by Martin Rathfelder (Director of the SHA)):

“The issue is blurred anyway as many GPs have found ways to “profit” through taking interests in companies providing services.”

People who do not hold the same views as McKinseys’ and Apax should be allowed to influence an incoming Labour government, whether they are or have been the leadership of the SHA or not. It is hoped that these alternative views do not merely act as a boring echochamber, and genuinely reflect the founding values of the NHS.

What the Lewisham decision is about, and, more importantly, what it isn’t about

R (on the application of LB of Lewisham and others) v Secretary of State for Health and the TSA for South London Hospitals NHS Trust High Court of Justice (Queen’s Bench Division) Administrative Court [2013] EWHC 2329 (Admin)

Judgment here

None of this of course was ever meant to happen (except it was, because the history is elegantly deciphered in “NHS SOS”, edited by Tallis and Davis). Remember this?

The Lewisham decision was taken relating to a specific legal problem, in a particular place at a particular time. Judge Silber therefore applied the law to that particular situation, and he specifically did not wish to go into the merits of the case. He just looked at how the decision was taken, which was a bad mess. Jeremy Hunt, the Secretary of State for Health, either received bad legal advice, or chose to ignore the legal advice he was given. There are useful lessons to be learnt from the judgment (“Judgment”) though, which is a beautiful piece of work. Certain issues were avoided altogether, such as how next to proceed (is there a need for a reconsultation? who should now make the decision? The Judgment does not discuss whether neoliberal economics produces the best outcome for patients in the National Health Service, nor does it opine on the eventual consequences of failure regimes around the country. It takes the case law further, but the danger is that too much can be read into its significance. However, in terms of morale and confidence, this was undoubtedly a much needed ‘boost’ for the patients, public and clinicians of Lewisham.

At the root of the problem, the Prime Minister had said:-

“What the Government and I specifically promised was that there should be no closures or reorganisations unless they had support from the GP commissioners, unless there was proper public and patient engagement and unless there was an evidence base. Let me be absolutely clear: unlike under the last Government when these closures and changes were imposed in a top-down way, if they do not meet those criteria, they will not happen.”

The draftsman of the parliamentary legislation is aware of the problem posed by the Secretary of State having a duty to provide a comprehensive NHS. This is, of course, the major faultline in English health policy, with both the Conservatives and Labour truly adamant about ‘comprehensive, free-at-the-point of use, universal’, while stories appear all the time – in a drip-drip fashion – about the manifestations of rationing. Again, Silber can only refer to the law as it was at the time in para. 61:

61 All these matters have to be considered against the background that under Section 1 of the 2006 Act, the Secretary of State has the duty of continuing the promotion in England of a comprehensive health service. Section 3 of the 2006 Act specifies the Secretary of State’s duty to provide or arrange the provision of a wide range of services (including hospital accommodation and services) to such extent as he considers necessary to meet all reasonable requirements. Section 2 gives the Secretary of State the power to provide other services as he considers appropriate for the purpose of discharging any duties conferred on him by the 2006 Act.

Against this is the backdrop that each NHS Trust is a separate financial and clinical entity, allowing for units to be ‘ringfenced’ as or when they run into financial or clinical problems. The problem has emerged where the parliamentary draftsman has found himself producing every voluminous legislation to cover any eventual possibility, which is why Silber is able to state confidently as a point of legal fact at para. 76:

76 It is clear that each NHS Trust is a separate entity, and this issue raises questions of statutory interpretation.

The tension in reconciling the needs of the entire National Health Service and local resource of allocation, of course, had to be addressed, and indeed it was. What is certain is the extent to which national policy will be sketched out for the strategic and operational management of the entire NHS, calling into question the mantra of Andy Burnham MP, “putting the ‘N’ back into NHS”.

81 Third, the Parliamentary draftsman chose to distinguish between “the interests of the Health Service” and those of the Trust.

What clearly emerged yesterday was that any-old promise does not produce a ‘legitimate expectation’ in this jurisdiction. This of course will also be great news for Nick Clegg after his tuition fees fiasco. Indeed, in my blogpost of July 7th 2013 for the “Socialist Health Association”, I wrote the following:

“And what about the actual law? R v. Inland Revenue Commissioners ex parte MFK Underwriting Agents Limited (1991) WLR 1545 in which Bingham LJ and Judge J stated that, for a statement to give rise to a legitimate expectation, it must be: