Home » NHS reorganisation (Page 2)

The section 75 NHS regulations exposed muddled thinking all round; but is there really no alternative?

It’s easy to lose sight of Labour’s fundamental question in terms of the economic model; viz, whether the State should, in fact, intervene in any failing #NHS healthcare (in a financial sense). That is what distinguishes it from neoliberal models of healthcare, including the New Labour one. It is a reasonable expectation that the healthcare regulators will uphold professional standards of the medical and nursing professions, whether in the public or private sector.

One of the most memorable experiences in my whole journey of the section 75 NHS regulations was Richard Bourne, the Chair of the Socialist Health Association, asking me what would probably happen at the end of the day. I originally replied saying that I was not an astrologer, but, as I thought about that question more, I became totally convinced it was a very reasonable question to ask. In management, private or public, when one is uncertain about the outcome, a perfectly valid tool is the ‘scenario analysis’, where one considers the various options and their likelihood of success. Also, if you really don’t know what the eventual outcome is, which might be the case, say, if you have to produce a complicated budget for the whole of the next year, you can to some extent ‘hedge your bets’ by doing a rolling forecast which updates your plan on the basis of virtually contemporaneous information.

Section 75 NHS regulations had become a very ‘Marmite issue’. Richard was right to pick up on the fact that the world would not necessarily implode with the successful resolution by the House of Lords of the second version of the regulations. On the other hand, the event itself marked a useful occasion for us all to take stock of where the overall ‘direction of travel’ was heading. Wednesday’s charge, led by Lord Phil Hunt, was as ‘good as it gets’. Reasons for why Labour in places produced a lack lustre attack is that some individuals themselves were alleged to have significant conflicts of interest, or some elderly Peers were unable to organise suitable accommodation so that they could negotiate the ‘late night’ vote. Lord Walton of Detchant, whom all junior neurologists will have encountered in their travels at some point in the UK, said convincingly he had a look at the Regulations, and felt that they would be OK even given the ‘torrent’ of communication he had personally received about it.

I certainly don’t wish to rehearse yet again the arguments for why the section 75 NHS regulations appears to be farming out the NHS to the private sector, but in the 1997 Labour manifesto, where Tony Blair was likely to win, Labour promised to abolish the purchaser-provider split. It didn’t. Labour likewise is promising now the repeal the current reincarnation of the Health and Social Care Act. It might not. There is substantial brand loyalty to Labour, over the NHS, such that the Conservatives would find it hard to emulate the goodwill of the public towards it that is shown to Labour. Given that the market has been implemented in the NHS, the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats are now arguing that they wish to make the market ‘a fair playing field’, which is of course a reasonable aspiration provided that a comprehensive NHS can be maintained for the public good.

Many have no fundamental objection to running a NHS most efficiently. I often find that health policy experts who have little clinical knowledge find themselves going on wild goose chases about efficiency in the NHS. For example, I remember the biggest barrier to progressing with a patient with an acute coronary syndrome is that it would be impossible to get a troponin blood result off the HISS computer system for hours, such that you would be forced to track somebody down from the laboratory itself. Co-ordinated care can mean better care. The best example I can think of is where a GP prescribes Viagra for a man with erectile problems in the morning, the patient collects all his new medication from the local chemist, the patient then takes the first tablet around lunchtime, the patient has sex with his partner in the evening, but unfortunately attends A&E in the evening for angina (chest pain). Modern advice (for example here) would argue that an emergency room should take a very cautious approach in administering nitrates, a first line medication for angina, within 24 hours of a dose of viagra. What a Doctor would do in this particular scenario is not something I wish to discuss, but it is simply to demonstrate that patient care would benefit from ‘joined up’ operational processes, where the emergency room doctor had knowledge of what had been prescribed etc. that day.

So, it probably was no wonder that there was ‘muddled thinking’ all round. Baroness Williams is a case in point. She acknowledges that many in the social media think that she personally, with the Liberal Democrats en masse, has ‘sold out’ on the NHS. And yet she talks about a deluge of misinformation from organisations such as 38 degrees who cannot be shot for being the messenger for a concerned public; that presumably is consistent with the Liberal Democrats yearning for ‘a fair society’? Lord Clement-Jones attacked the person not the ball, advancing the argument that lawyers will always provide a legal opinion which favours the client. However, many agree with David Lock QC in his concerns on how the legislation could be interpreted to go further than the previously existant legislation from Labour over the Competition and Cooperation Panel. Indeed, Labour in the late 2000s had tried to legislate for public contracts, with attention to how their statutory instruments might be consistent with EU competition law.

However, the muddled thinking did not stop there. Only a few people consistently explained why the regulations were a ‘step too far’, and it is no small achievement that the original set of regulations had to be abandoned. The general public themselves can be legitimately blamed for muddled thinking. The general impression is that they resent bankers being awarded bonuses, resent the explosion of the deficit due to the banking crisis, but did not wish the banks to implode. The general impression is also they are happy with the previously high satisfaction ratings of the NHS, do not wish the NHS budget to be cut, and yet do not want ‘failing NHS trusts’ to be shut down altogether. Meanwhile, the Francis report exposed sheer horror in how some patients and their relatives or families experienced care from the NHS, and there are concerns that similar phenomena might be exposed in other Trusts. All of this is totally cognitively dissonant with the idea of ‘efficiency savings’ in the NHS, with billions of surplus being given back to the Treasury instead of frontline patient care. The issue about whether private companies should be allowed to make a profit from healthcare is a difficult one, when compared to an issue of whether parents can have a ‘choice’ as to whether to send their children to independent schools. However, many members of the general public would prefer any profit made in the NHS to be put back into patient care, rather than lining the pockets of shareholders or producing healthy balance sheets of private equity investors. The section 75 NHS regulations has done nothing for a discussion about how to maximise patient safety, nor the value of employees in the NHS. Managers in the NHS appear to be pre-occupied with ‘excellence awards’, innovation and leadership, but appear to have lost sight of the big picture of the real distress shown by some working at the coal face in the NHS.

Monitor, the new economics healthcare regulator, has a pivotal part to play; but they are an economic regulator ensuring fair competition, so it is hard to see as yet how they can best secure value for the patient rather than dividend for the providers. This is a Circle to be squared (pardon the pun). Possibly the only way to ensure that the NHS does not become a ‘race to the bottom’ (where “I don’t care who provides my healthcare as long as it’s the most efficient” becomes “I don’t care who provides my healthcare as long as it’s the cheapest and delivers most profit for the private provider)” is to ensure that people who are clinically skilled are involved in procurement decisions, or in regulatory decisions. This is the only way where yet another one of Earl Howe’s promises might be fulfilled; that local commissioners can commission services, even if they are only available from the NHS, if it happens that ‘there is no alternative’. Possibly doom-and-gloom is not needed yet, but it cannot be said that Lord Warner did much to inspire faith as the only Labour peer to vote against Labour’s “fatal motion”. Many people did indeed share the sense of despair felt by Lord Owen before, during and after the debate. However, Labour has to react to the present and think about the future. It cannot rewind much of the past, for example current PFI contracts in progress. The public have already exhausted themselves with the debate over ‘who is to blame over PFI?’, where both Labour and Conservatives have contributed in different ways to the implementation of PFI, and there are still some who believe that the benefits of infrastructure spending through PFI are yet to be seen. But blaming people now is probably a poor way to use precious resources, and there is a sense of ‘in moving forward, I wouldn’t start from here.’ Labour has to think now carefully of what exactly it is that it intends to repeal and reverse. Its fundamental problem, apart from sustainability, is to what extent the State should ‘bail out’ parts of the system which, for whatever reason, aren’t working; but this is essentially the heart of the neoliberal v socialism debate, without using such loaded language?

Shibley tweets at @legalaware.

Should we be choosing chocolates rather than picking cherries?

You are advised to read this article in bits, according to which parts interest you. If you would like to engage constructively in some of the issues here, I can easily be reached on my twitter thread @legalaware

Introduction

There are potentially very many false dichotomies in the debate over English healthcare: private vs public, efficient vs inefficient, etc. While we wait to halt the privatisation of the NHS, it might be better for our morale to think positively that some private healthcare providers are choosing different chocolates, rather than picking cherries, but ultimately the purpose of the State might be to aspire to cover all illnesses, irrespective of financial ability to pay, and this is of course a very admirable one. The problem is: in an unfettered market, the equilibrium will simply be the conditions which are most profitable for providers are ‘covered well’, but in the new-look NHS (“Neo NHS”), some conditions will be massively under-represented and could become very costly for CCGs covering these patients?

Whenever you introduce a market, you will always experience the phenomenon of “cherry picking”. The question in the short term must be: what do we do with the fact that certain companies will wish to pick their cherries, so that directors can fulfil their statutory duty under s.172 Companies Act [2006] to “promote the success of the company”, i.e. maximise shareholder dividend. For some reason, the electorate does not wish to be open about the privatisation of the NHS, even though market-oriented health care reforms have been high on the political agenda in many countries (e.g. Erik M. van Barneveld and colleagues, 2000). The response of the left tends to be a binary ‘boom-or-bust’ approach; for example, having the Act repealed, having no markets etc., and ideally ‘in moving forward, I wouldn’t start from here‘. The problem however is that we can all become trapped in ideology, and become attached to fundamental principles. Some would say that some issues are “clear red line” issues such as comprehensiveness or totality of the NHS, but, in light of the ongoing active discussions about rationing, it is clear that certain issues need to be confronted sooner rather than later. This article will consider how ‘cherrypicking’ has been addressed, and possible ways of dealing with it. It is only meant to be an introduction to this complicated issue, however.

Use of the term “cherry-picking”

One of the criticisms made about the NHS privatisation is that the outcome of the process will see some providers “cherry-picking” services. The issue about this term is that it sounds pejorative, even if this is your image of a bowl of cherries:

Legal origin of cherry picking as a concept

The legal use of the term “creamskimming”, in a different jurisdiction (the US), appears to have originated in a 1951 Supreme Court case, Panhandle Eastern Pipe Line Co. v. Michigan Public Service Commission [1951].The appellant Panhandle, an interstate gas pipeline company, launched a program to secure for itself large industrial accounts from customers already being served by the Michigan Consolidated Gas Company, a local distribution company franchised under Michigan law. The Supreme Court of the United States refused to grant Panhandle a purported “right to compete for the cream of the volume business” within Consolidated’s customer base “without regard to the local public convenience or necessity.”

Jim Chen has provided that the following definition of ‘cherrypicking’ should be used:

““Cream skimming” should be defined as “the practice of targeting only the customers that are the least expensive and most profitable for the incumbent firm to serve, thereby undercutting the incumbent firm’s ability to provide service throughout its service area.””

Chen quickly goes onto say the following:

“The unfortunate truth is that regulated incumbents have long exhibited a tendency to condemn lawful, desirable competition simply by invoking the pejorative label of “cream skimming.” Alfred Kahn diagnosed the urge long ago: “if one defines as ‘creamy’ whatever business is worth competing for,” one will reach the absurd conclusion that “all competition is by definition cream skimming.”

Indeed, at the time of another massive NHS reorganisation in 1974, Alan Reynolds writing in the Harvard Business Review observed from the same viewpoint:

“Whenever a monopoly or cartel pleads with the government to ban or restrain competitors, it invariably accuses the newcomers of skimming the “cream” and leaving the less profitable business to established companies.”

“Cherry-picking” as a political (and otherwise) device has been an on-running theme in the discussions over the Health and Social Care Act [2012]. Cherry picking (sometimes also referred to as cream skimming) is a term that generally refers to the act of selecting only the best or most desirable candidates from any group. As Mark Armstrong explains, “It is a common regulatory practice to “assist entry”, especially in the early stages of liberalisation.” In the context of healthcare provision, it is typically used to describe instances where private healthcare providers select patients which are of the highest value and lowest risk to them, referring less desirable patients, those with conditions likely to require more complex treatment, back to the NHS.

As the Health and Social Care Act introduces markets to many more areas of the NHS, cherry picking is likely to increase. As as this increases, public scrutiny of it is likely to increase, and it’s pretty likely that private suppliers are already organising their PR for this. Indeed, Alan Reynolds (1974) had advised the following to (presumably predominantly corporate) readers of his article in the Harvard Business Review:

“Newcomers accused of cream skimming should force their accusers to be quite explicit about how much cream there is, where it comes from, and where it goes. Where did the monopoly get the mandate to run this [] program. What are exactly are the objectives? Is there a better way to achieve them. Who audits the results? Without such substance, the cream-skimming cliché has about as much credibility as an unsupported accusation that competition is unfair. There are plenty of epithets for those who charge low prices, but they relatively merit attention.”

The importance of the regulator

Cherrypicking poses a difficult problem for the regulators – as predatory pricing should not be confused with improved competition in financial markets, and may not in fact be illegal per se in some jurisdictions. This has been a “known issue” for some time, see for example the memorandum submitted by Monitor, the “sector regulator” dated 19th July 2011:

There was also concern that the Health and Social Care Bill would enable private providers to ‘cherry pick’ routine and less complex healthcare services and interventions that are cheaper to provide and more profitable. The concern was that this would leave the NHS to deal with the higher-cost, more complex and long-term conditions with inadequate prices, causing the destabilisation of local hospitals. A proposal has now been included in the Bill to address this concern, which means that Monitor would be given a specific duty to set prices that reflect underlying costs, so there should no longer be any cherries to pick. Cherry-picking should not be an issue if NHS prices are designed to reflect complexity of treatment so that appropriate payments are made for both simple and complex services.

In his latest advice to 38Degrees, David Lock indeed refers to “cherry picking”:

“Private providers will seek, for example, cherry pick services which are relatively cost-effective to deliver may be able to put pressure on the commissioner to divide out those services from others on the grounds that the private provider can provide those services more economically or that to bundle up these services with other services amounts to anticompetitive behaviour. This is likely to be an area of intense debate within the NHS as private providers seek to use the (in places unclear) wording of the Regulations to put pressure on CCGs to divide contracts. Some CCGs may be able to resist this pressure but others are likely to succumb to this pressure. It follows that whilst the wording of the regulations does not place any duties onCCGs explicitly to divide contracts, in practice this happen for the reasons outlined above.”

So there is patently a debate to be had. History has provided that there can be a huge problem in effecting market entry, and the only way you can achieve anything like ‘good competition’ is to avoid a situation with only a few suppliers. Cited in Armstrong (2000), the privatisation of BT is noted.

“In Britain, the first competitor was explicitly granted favourable access to BT’s network, and in particular was made exempt from making any contribution to BT’s access deficit (see DTI, 1991, page 70):

“it is reasonable to exempt a new competitor [...] from the [access deficit] contribution in the early stages of its business development, in the interests of helping it get started. If this were not done, the ability of the newcomer to compete might be inhibited because of the economies of scale available to the incumbent and competition might never become established.“

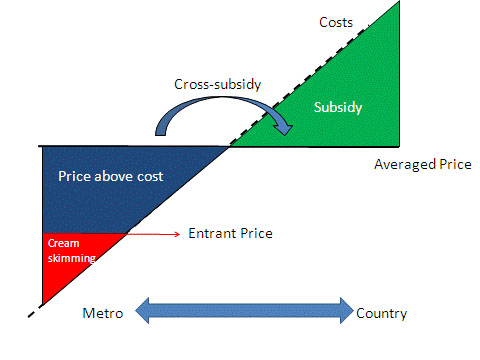

Cross-subsidies

A possibly way to address this is through the use of “cross-subsidies”?

As shown here (diagram produced originally in http://www.ictregulationtoolkit.org/en/Section.3545.html) this could be a mechanism of addressing a potential market failure, but a cross-subsidy may indeed itself be anti-competitive when a firm with market power prices services in less competitive markets higher so that it can have lower price for services it sells into competitive markets.

The issue of “cross-subsidies” has been addressed in other sectors: for example: “Incumbents complain about “cream-skimming” competition allowed by the cross-subsidies above. So, regulators assist incumbents with price rebalancing to meet competition, which generally increases line rentals so that call prices can fall. This is a politically sensitive process because raising access prices disadvantages the poorer users who make fewer calls; so some policy direction may be needed.”

But politically, does admitting there are cross-subsidies constitute a failure of the market? This is again where the patient may not be given complete information. Indeed, unless you happen to be medically qualified, you will not share the level of information a clinician may have in making a decision about your own care. Like all other aspects, it is quite possible that the general public, i.e. real patients, will not be involved in this discussion, but it does indeed happen in other sectors, for example:

Respondents knew that cross-subsidising goes on – at least to some extent – in other areas. They knew, for example, that they paid some additional, albeit unknown, amount in the supermarket to cover the cost of shoplifting, breakages and in-store damage to goods. They suspected that the cost of insurance premiums must allow for fraudulent claims. They were less aware that train fares include a subsidy to cover revenue lost through fare dodging, or that mortgage rates compensate lenders for defaulters, or that electricity and gas customers in rural areas are more expensive to service than those in urban areas but the cost is spread across all customers. There was no awareness at all of a cross-subsidy in the water bill.

Payment-by-results?

The Government has decided to tackle this through “payment by results”. As Crispin Dowler and Dave West have recently reported in the Health Services Journal,

“Commissioners may need to increase the prices they pay to NHS hospitals left with more complex workloads after other providers have “cherry picked” the easier patients, new Department of Health guidance shows.

… Rules introduced this year gave commissioners the flexibility to cut the tariffs they pay to such providers, but did not mandate increased payments to hospitals that are left with disproportionate numbers of complex and costly patients.

However, the guidance for 2013-14 appears to endorse above- as well as below-tariff payments.

“Commissioners will be required to base any decision to reduce tariffs on clear evidence which shows that the provider would be over-reimbursed at the national tariff rate,” it states. “They must also give consideration to the potential for other providers to be left with an altered, more costly, casemix which may therefore also require a funding adjustment.”

As was indicated in the draft document published in December, the final PbR guidance also includes a list of high-volume procedures that may be more susceptible to “cherry picking”.”

Conclusion

So, what should the response be from an organisation interested in socialism? There is no doubt that this discussion has advanced well beyond “whether it’s marketisation or it’s privatisation”. The legal instruments will come into force on 1 April 2013, and this article has no intention of proposing a campaigning thrust for ‘saving the NHS’. However, what has been presented here has been some indication of the language of ‘cherry picking’, what the potential issues about ‘cherry picking’ in markets might be, and how these might be mitigated against by the regulators. The problem is: in an unfettered market, the equilibrium will simply be the conditions which are most profitable for providers are ‘covered well’, but in the new-look NHS (“Neo NHS”), some conditions will be massively under-represented and could become very costly for CCGs covering these patients? Time will tell how this evolves.

Further reading

February 2000: Mark Armstrong (Nuffield College, Oxford OX1 1NF) Regulation and Inefficient Entry.

Department of Trade and Industry (1991), Competition and Choice: Telecommunications

Policy for the 1990s, London, HMSO.

Alan Reynolds. November – December 1974. A kind word for cream-skimming. pp.113-118.

Erik M. van Barneveld, Leida M, Lamers, Ren6 C.J.A. van Vliet and Wynand P.M.M. van de Ven. (2000) Ignoring small predictable profits and losses: a new approach for measuring incentives for cream skimming. Health Care Management Science 3: 131-40.

Patient choice or a choice of a good procurement lawyer?

John Major famously introduced “The Patients’ Charter”, which set out a number of rights for NHS patients. It was originally introduced in 1991, under the now Conservative government, and was revised in 1995 and 1997. The charter specifically set out rights in service areas including general practice, hospital treatment, community treatment, ambulance, dental, optical, pharmaceutical and maternity. ” Patient choice has of course been the “buzz word” in the amateurish-marketing of the NHS changes, but they hide a devillish agenda of substantial legal considerations.

The revised regulations (“Regulations”) [2013/500], are here. The Regulations impose obligations on CCG commissioners to act in a transparent and proportionate way and to treat providers equally and in a nondiscriminatory way (see Regulation 3). In doing this the Regulations substantially replicate the duties which are already imposed by EU law on NHS commissioners. The way in which EU law impacts on NHS commissioning was explored in R (Ota Lloyd) v Gloucestershire PCT. In that case, Lock himself describes that:

The legal challenge by local Gloucestershire resident, Michael Lloyd, to the decision of the Gloucestershire PCT to outsource its community services to a Community Interest Company raised serious questions for NHS commissioners. The case was settled on day two, so there will not be a court judgment which explains how the law works in this area. That may (and here I speculate) be a great relief to the Department of Health who may not have welcomed the Judge expressing her views on whether the PCT was acting lawfully or not, and thus constraining future NHS management decisions. However EU procurement law is now a big issue for the NHS and, on a purely personal basis, it seems that the cases raises serious issues for the NHS.

In his advice on the latest Regulations, David Lock QC outlines that,

“A … problem arises where there is more than one potential provider for a range of NHS services but where it is in the interests of integration of local services for a contract to be placed with a local hospital provider. This will happen for example in any urban conurbation where there is more than one major hospital within a reasonable ambulance ride from the CCG area. In such circumstances there is more than one potential provider of A & E services and therefore more than one provider of other acute services. A CCG may feel it has a strategic interest in maintaining services at its local hospital but, in such circumstances, the CCG will be forced to run an expensive competition between acute providers each year before it is able to relect the annual acute services contract. It is difficult to see how such a process can benefit the NHS as a whole.”

This is explained in full in “advice no. 2″ point 15:

“One key question is whether commissioners would be entitled to take a strategic decision to avoid a competition for a contract if they took view that it would be in the interests of patients for a particular service to be integrated together with other health or social care services that were already being provided by an existing NHS provider. This is clearly the thinking which led to the change to Regulation 2 which specifically allows NHS commissioners to take account of the benefits of services being provided in an integrated way (including with other health care services, healthrelated services or social care services). However that objective cannot be achieved in practice if, in making the decision under Regulation 5 whether a commissioner can lawfully avoid having a competition, the only test a commissioner is permitted to apply is whether the contract relating to those services (as opposed to other services) is only capable of being delivered by a single provider. If the answer to that question is that the contract is capable of being delivered by more than one provider, the CCG must hold a competition even if it is not in the interests of patients to do so.”

Meanwhile, current recommendations are for four A&E departments in hospitals in north-west London to be closed. The departments at Ealing, Central Middlesex, Charing Cross and Hammersmith hospitals would be downgraded to 24/7 urgent care centres and would no longer take “blue light patients”. Five “major hospitals” – Chelsea and Westminster, Hillingdon, Northwick Park, St Mary’s in Paddington and West Middlesex – would have more specialist and experienced doctors available more of the time.

It is this question of societal needs above individual patient needs which keeps on coming back to bite this debate on the arse. In R v Cambridge Health Authority Ex Parte B (A minor) [1995] EWCA Civ 49, Lord Bingham provides that:

“I have no doubt that in a perfect world any treatment which a patient, or a patient’s family,sought would be provided if doctors were willing to give it, no matter how much it cost, particularly when a life was potentially at stake. It would however, in my view, be shutting one’s eyes to the real world if the court were to proceed on the basis that we do live in such a world. It is common knowledge that health authorities of all kinds are constantly pressed to make ends meet. They cannot pay their nurses as much as they would like; they cannot provide all the treatments they would like; they cannot purchase all the extremely expensive medical equipment they would like; they cannot carry out all the research they would like; they cannot build all the hospitals and specialist units they would like. Difficult and agonising judgments have to be made as to how a limited budget is best allocated to the maximum advantage of the maximum number of patients. That is not a judgment which the court can make. In my judgment, it is not something that a health authority such as this Authority can be fairly criticised for not advancing before the court.”

This is potentially a very dangerous situation for clinical commissioning groups (“CCGs). If lawyers and accountants acting on behalf of private healthcare suppliers can find any way in which competition law was not followed in the way the contract was awarded then Monitor can potentially declare the contract void. The CCG will find itself forced into certain decisions through having limited time and financial resources, whereas the private provider may be in a position submit an elegant presentation or pitch.

The reality, and this will become clear in time, is that this is a ‘gravy train’ for procurement lawyers, and it is not clear where the money to defend the CCGs decisions “on behalf of patients” will actually come from. Prof. Colin Leys gives a very good example of how this has concerned concern, only yesterday in the Guardian:

“How it will work was strikingly illustrated in Hackney last month. Some Hackney GPs and their patients were deeply dissatisfied with the out-of-hours GP service provided by Harmoni, a private company that is the subject of well-publicised allegations of staff shortages and other problems, which the company refutes.

The GPs formed a social enterprise to take over the service when Harmoni’s contract expired, and the primary care trust (PCT) wrote to say they were expected to do so from 1 April. But at the last minute the PCT rescinded this decision and extended Harmoni’s contract.

Furious Hackney residents and GPs wanted to know why. The answer was that lawyers for both the PCT and the new CCG had advised that there was a risk that Harmoni’s owners would take legal action if the social enterprise was allowed to take over without a new bidding process. The PCT chair told a meeting of Hackney council’s scrutiny committee he felt it was his duty to avoid the risk of major legal costs.

So, this is the new reality. Where any risk of legal action exists, CCGs’ lawyers will naturally advise them to avoid it. How many CCGs will be willing to disregard this advice? The ultimately decisive factor in what gets commissioned looks likely to be not the wishes of CCGs (let alone patients, or voters), but corporate legal firepower.”

Integrated care – there’s an app for that! A hypothetical case study.

Innovation and integrated care

Andrew Neil reminded us this morning on ‘The Sunday Politics’ that there are currently around 4 million individuals who don’t have access to the internet. Prof Michael Porter, chair of strategy at the Harvard Business School, has for a long time reminded us that sectors which have competitive advantage are not necessarily those which are cutting-edge technologically, but his colleague Prof Clay Christensen, chair of innovation at the same institution, has been seminal in introducing the concept of ‘disruptive innovation’. An introduction to this area is here. The central theory of Christensen’s work is the dichotomy of sustaining and disruptive innovation. A sustaining innovation hardly results in the downfall of established companies because it improves the performance of existing products along the dimensions that mainstream customers value. Disruptive innovation, on the other hand, will often have characteristics that traditional customer segments may not want, at least initially. Such innovations will appear as cheaper, simpler and even with inferior quality if compared to existing products, but some marginal or new segment will value it. (more…)

‘Fixing the broken delivery system: the case for change” – Dean’s lecture series, City University

Prof Stanton Newman, Dean of School of Health Sciences at City University, introduced Prof Chris Ham this evening. Chris Ham is of course extremely well known as the Chief Executive of the King’s Fund.

He is also engaged directly in clinical work and holds a regular clinic at University College Hospital mainly with referrals from medical and surgical colleagues in the hospital and also from primary care.He is the Principal Investigator on the Whole Systems Demonstrator Project funded by the Department of Health to evaluate the role of assistive technologies in health and social care. The studies in this programme constitute the largest randomized controlled trials on the role and impact of telehealth and telecare devices. The whole system demonstrator project is a comprehensive evaluation of these devices to inform policy. In addition his group is conducting research on the role of them portable devices in diabetes and web-based applications to improve the management of chronic conditions.

The biography of Prof Ham appears here:

Chris Ham took up his post as Chief Executive of The King’s Fund in April 2010.

He has been Professor of Health Policy and Management at the University of Birmingham, England since 1992. From 2000 to 2004 he was seconded to the Department of Health, where he was Director of the Strategy Unit, working with ministers on NHS reform. Chris is the author of 20 books and numerous articles about health policy and management. Chris was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Kent in 2012.

Chris has advised the WHO and the World Bank and has served as a consultant to governments in a number of countries. He is an honorary fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of London and of the Royal College of General Practitioners, an honorary professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, a companion of the Institute of Healthcare Management, and a visiting professor at the University of Surrey.

Chris was a governor and then a non-executive director of the Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust between 2007 and 2010. He has also served as a governor of the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation and the Health Foundation.

In 2004 he was awarded a CBE for his services to the National Health Service.

Rather than privatisation being the main challenge, Ham believes that inertia is the main challenge. Ham and colleagues will be producing constructive comments on how change can happen on scale and at pace. The King’s Fund is ‘the middle ground’ between theory and practice, but in an applied practical capacity. ‘This interest gets me out of bed in the morning, to improve health and healthcare’.

Chris Ham’s presentation

There are four burning platforms, not an inappropriate metaphor for health and social care.

The first burning platform is money. There are important differences in the four country, with no growth. Given the state of the economy, it could be a decade for austerity for public services including the NHS. We’ve had seven years of ‘feast’, perhaps followed by seven years of ‘famine’. After eighteen months, the situation is reasonably good. The pay freeze has helped to maintain a surplus. At a local level, there are growing financial pressures. An increasing number of organisations find themselves in deficit, struggling. The number of organisations struggle will increase.

After 18 months, it will be a test to ensure standards of patient care are maintained. John Appleby published a report on ‘Improving NHS productivity: more with the same not more of the same’. Prof David Nicholson has sought £20 bn “efficiency savings”. Everybody has to play a part in ‘Nicholson Challenge’, and this can be approached through an inverted triangle. Key decisions are made in the clinical microsystems, e.g. GPs, nurses, AHPs; prescribing, referrals, length of stay of patients, etc. It is the sum of these clinical decisions that will account for £10 bn of how the health budget is spent. Every clinical team has to eliminate waste, freeing up money for investment.

GPs were asked about the best ways of introducing efficiency savings. There is a lot of apparent agreement between GPs and hospital doctors; better coordination of care, and increased collaboration, between GPs and other services. At the time they were working on ‘Clinical and service integration: the route to improved outcomes” by Natasha Curry and Chris Ham. Getting clinical teams collaborating, and getting care for elderly people more joined-up. The means-to-the-end is better value for the resources being committed, and this paper aims to provide the evidence base from various research studies and countries, to demonstrate evidence and experience towards greater integration. The evidence is seen as ‘good enough’ to justify greater integration.

The second burning platform: the Health and Social Care Act 2012.

What does this mean?

- Massive organisational change

- Loss of experienced managers

- Increased complexity

- A focus on structures and not services

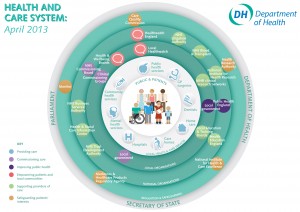

The simplified streamline map of the Department of Health (April 2013)

What does this mean?

Thatcher, Blair and Milburn started on this journey. Next chapter is the extension of choice and competition, with a bigger role for GP-led commissioning through 212 Clinical Commission Groups in England. There will be a new NHS Commissioning Board will have a major influence and its role viz a viz CCGs will be criticial. Provider reform/failure is well underway. Several healthcare providers are in financial difficulties. In South London Trust, a trust is bankrupt, and has been subject to administration. Peterborough Foundation NHS Trust has been in financial difficulty. The public will be worried about whether the hospital, GP, community nurse, are still there, and therefore whether failure is small but increasing.

The key document from the King’s Fund and the Institute of Government is Nick Timmins, “Never again?”. Timmins had unprecedented access to people involved in the genesis of the Act, a ‘who done it’ of health policy. A new team is appointed at the beginning of September. This does not signal a major change in the direction of reform. More emphasis will be placed on presentation and communication of the government’s plans. The big political challenges are about service reconfigurations, especially in hospitals.

The third burning platform is the Francis Report. There will be a delay. It will be produced very early in January 2013, bringing quality back onto the agenda. Supervisory bodies, and the role of CQCs and Monitors, in Mid Staffs NHS Foundation Trust will be scrutinised, considering systematic failures. This report will add ‘fuel to the fire’.

The government has put into place a mechanism for safeguarding quality in the NHS (National Quality Board 2010).

There are three lines of defence. The first line of defence should be the front line teams delivering care. The second line should be organisational leadership at the board level; are they talking about finance, or taking patient safety and quality-of-care seriously? The third line should be regulators and others. Organisational leadership and culture at all levels and staff engagement are critical. A focus on regulation could be erroneous, Ham believes. CQC must bear its share of responsibility, under David Bearn. You have to be realistic about what a regulator can do, and what a regulator cannot do. The experience and credibility of people who go on visits will have to be scrutinised. This will project on the King’s Fund RADAR early in the new year.

The fourth burning platform is the most important, and critically important. It is about future of services, coming from real and welcome improvements in the NHS. We have moved from very long waiting times in the NHS. NHS performance has improved greatly. Despite this, the model for health and care delivery is outmoded. We are really feeling the effects of overinvesting in hospitals and care homes, but tolerated average improvements in general practice, but been slow in technology and innovation uptake. There is a fundamental clinical, compelling, case as to how these services are provided in future.

- Report published at the beginning of September produces a foundation, hopefully. The UK has the second highest rate of mortality amenable to health care among16 high income nations, despite recent falls in death rates (Nolte and McKee, 2011). 10,000 lives would be saved each year, if England achieved survival rates at the level of the Euopean best.

- As many as 1,500 children a year might not die if the UK performed as well as Sweden, in relation to illnesses that rely on first-cass care, such as asthma and pneumonia.

- There is excess mortality in hospitals at weekends (Dr Foster Intelligence, 2011), and in London alone there would be a minimum of 500 fewer deaths a year, if the weekend mortality rate were the same as the weekday rate.

- More than half of 100 acute hospitals inspected by Care Quality Commission in 2011 were non-compliant with standards of dignity and nutrition for older people, or were found to be cause of concern (Care Quality Commission, 2011).

We have a lot of work to do: the report published by the King’s Fund is “Transforming the delivery of health and social care: the case for fundamrntal change”. It is interesting to compare the data to international data, in the form of ‘Commonwealth Fund International Ranking’. Netherland ranked first, and the UK came 2nd. Ten years ago, the rankings would be near the bottom. Long, healthy, productive lives comes 6th out of 7th (Nolte and McKee, 2011), and patient-centred care we come out bottom.

A possible future model of care might therefore have:

- Enhancing the role of patients and users in the care team (chronic diseases, long term conditions, expert patient programme)

- Changing professional routes

- Rethinking the location of care (too much reliance on nursing homes and care homes, too much focus on acute trusts)

- Using new information and communication technologies

- Harnessing the potential of new medical technologies (?better use of smartphones)

- Making intelligent use of data and information

The report deliberately does not spell out details.

“Fixing the broken system” would therefore consist of:

- Fundamental and rapid changes is needed

- More consistent standards of primary care

- Primary care working at scale through networks

- Integrated out of hospital care working 24/7

- Acute hospitals working in collaboration and with reduced role over time.

- The home as the hub of care with range of supported housing options (older people would prefer to be in the own homes, and telecare might be more important in future).

In an article dramatically titled ‘closing one in three hospitals would improve patient care’, the Guardian described:

Shutting a third of hospitals would improve quality of care and should be part of changes to the NHS that would let patients see their GP or have surgery at the weekend, a leading doctor has claimed. A dramatic centralisation of services would benefit patients by putting larger numbers of doctors in fewer places, with the inconvenience for the sick and their loved ones of having to travel further outweighed by better treatment, according to Professor Tim Evans of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP).

This is of course much of what the King’s Fund has been said before. But there has only been limited progress in effecting change this time round at scale and at pace. The issues are urgent.

Tackling the challenge of inertia

Potential strategies might include:

- Opening up the market to new providers, with new and better business models. Competition should be a tactic not a strategy.

- Existing providers to support staff to innovate. A lot of change should not come from outside, but from within.

- Decommissioning outmoded models of care

- Recognising the key role of clinical and managerial leaders, taking on politicians and vested interests.

- Risk taking needs support from politicians. We will not make progress unless there is a degree of innovation.

Selected references

Care Quality Commission (2011). Dignity and Nutrition: Inspection programme. Newcastle upon Tyne: CQC.

Dr Foster Intelligence (2011). Inside your hospital. Dr Foster Hospital Guide. 2001–2011.

Nolte E, McKee M (2011). ‘Variations in amenable mortality – trends in 16 high-income nations’. Health Policy, vol 103 no 1, pp 47–52.

‘Work in progress’ : Andy Burnham’s 2012 conference speech throws up tough challenges

Andy Burnham has vowed to reverse the “rapid” privatisation of NHS hospitals in England if Labour wins power. In particular, Mr Burnham said he feared the new freedom for hospitals to earn 49% of their income from private work would “damage the character and culture” of the NHS and take it closer to an American model.

The issue of fragmentation of the NHS is a genuine problem in the NHS, as enacted this year. This is manifest in a number of different guises, such as lack of clarity as to which private entity owns what for local services, the abolition of statutory bodies involved in healthcare (such as the National Patient Safety Agency and the Health Protection Agency), and the phenomenon of “postcode lottery” in healthcare provision.

Andy Burnham clearly wishes “Labour values” of collaboration and solidarity to be pervasive in an equitable National Health Service, rather than competition, where there are winners and losers. This is particularly interesting from a business management sense, as it has long been a source of academic interest in innovation management how the “innovators’ dilemma” is solved in the private sector. This is the practical business question posed by Prof Clay Christensen, professorial fellow in innovation at Harvard, as to how it is possible, that, amongst private entities in the market place, business entities can secure competitive advantage, while working together sharing knowledge in seamless collaboration.

It seems pretty likely that, even if Labour win the 2015 general election and the Health and Social Act (2012) is repealed, commissioning will exist in some form, with Labour taking forward ‘best practice’ from the experiences of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs). There is no inkling that, whilst certain structures are in the process of being abolished for some time (such as the PCTs and SHAs), the CCGS and NHS Foundation Trusts will follow suit. Indeed, Professor Brian Edwards, special adviser to the Institute of Healthcare Managers, said he was “appalled and frustrated” at news the Francis Report would not be published until January 2013, and called it “a cruel blow” to the families of victims. This report discusses the failings at hospitals in Mid Staffordshire between 2005 and 2009, and is anticipated to be invaluable in developing further NHS foundation trusts.

Integration in person-centred care has always been a hallmark of excellent medical care, and Burnham keens to bring this out as a dominant theme in components of his new Health Bill in 2015 or 2016 if elected. When patients present to their G.P., they simply do not present as isolated medical diagnoses. For example, if an elderly patient, who may incidentally have a probable diagnosis of dementia, falls, a GP would be concerned with the patient is at risk of a fracture due to underlying osteoporosis, has poor eyesight due to a cataract for example, or leads a life in a cluttered home environment due to lack of social care. There are a plethora of problems which are likely to cause an individual to come into contact with the NHS, and the integration of health and social care is indeed entirely in keeping with Nye Bevan’s original aspiration for the NHS. The ideal would be of course to have an integrated health and social care service, but much time (and money) has been lost by the Coalition kicking the Dilnot review ‘into the long grass’ when we were already supposedly meant to be looking for greater efficiencies through the Nicholson Challenge.

Moves are clearly afoot as to who is providing the services, with various morphologies in terminology (for example “NHS preferred provider”, “any willing provider”, or “any qualified provider”). Closer to home for the current delegates in Manchester, patients will be taken to hospital by a bus company after the North West Ambulance Service (NWAS) failed to win a contract. It will not affect 999 emergency call-outs. Arriva, which run bus services throughout Greater Manchester, will replace NWAS which currently runs the service but was outbid by Arriva after the the service was put out to tender.

Chris Ham, Chief Executive of the Kings Fund, has concerns which are perfectly fair, in response:

“Andy Burnham has outlined a vision for the future of health and social care which accentuates the differences between the Labour Party and the government on the NHS. He is right to stress the need for fundamental change in health and social care services. Our own work has made the case for radical changes to ensure the NHS is fit to meet the challenges of the future as the population ages and health needs change.

This includes moving care closer to people’s homes and re-thinking the role of hospitals which must change to improve the quality of specialist services and better meet the needs of older patients. We also welcome his emphasis on delivering integrated care – the challenge now is to move integrated care from the policy arena and make it happen across the country at scale and pace.

However, while the long term vision is ambitious, the details of Labour’s plans are sketchy. A number of questions will need to be answered in the policy review announced today. For example, it is not clear how local authorities could take on the role of commissioning health care without further structural upheaval. And despite the Shadow Chancellor’s pledge earlier in the week, it is not clear how Labour would ensure adequate funding for social care.”

Text of speech given this morning in Manchester.

Conference, my thanks to everyone who has spoken so passionately today and I take note of the composite.

A year ago, I asked for your help.

To join the fight to defend the NHS – the ultimate symbol of Ed’s One Nation Britain.

You couldn’t have done more.

You helped me mount a Drop the Bill campaign that shook this Coalition to its core.

Dave’s NHS Break-Up Bill was dead in the water until Nick gave it the kiss of life.

NHS privatisation – courtesy of the Lib Dems. Don’t ever let them forget that.

We didn’t win, but all was not lost.

We reminded people of the strength there still is in this Labour movement of ours when we fight as one, unions and Party together, for the things we hold in common.

We stood up for thousands of NHS staff like those with us today who saw Labour defending the values to which they have devoted their working lives.

And we spoke for the country – for patients and people everywhere who truly value the health service Labour created and don’t want to see it broken down.

Conference, our job now is to give them hope.

To put Labour at the heart of a new coalition for the NHS.

To set out a Labour alternative to Cameron’s market.

To make the next election a choice between two futures for our NHS.

They inherited from us a self-confident and successful NHS.

In just two years, they have reduced it to a service demoralised, destabilised, fearful of the future.

The N in NHS under sustained attack.

A postcode lottery running riot – older people denied cataract and hip operations.

NHS privatisation at a pace and scale never seen before.

Be warned – Cameron’s Great NHS Carve-Up is coming to your community.

As we speak, contracts are being signed in the single biggest act of privatisation the NHS has ever seen.

398 NHS community services all over England – worth over a quarter of a billion pounds – out to open tender.

At least 37 private bidders – and yes, friends of Dave amongst the winners.

Not the choice of GPs, who we were told would be in control.

But a forced privatisation ordered from the top.

And a secret privatisation – details hidden under “commercial confidentiality” – but exposed today in Labour’s NHS Check.

Our country’s most-valued institution broken up, sold off, sold out – all under a news black-out.

It’s not just community services.

From this week, hospitals can earn up to half their income from treating private patients. Already, plans emerging for a massive expansion in private work, meaning longer waits for NHS patients.

And here in Greater Manchester – Arriva, a private bus company, now in charge of your ambulances.

When you said three letters would be your priority, Mr Cameron, people didn’t realise you meant a business priority for your friends.

Conference, I now have a huge responsibility to you all to challenge it.

Every single month until the Election, Jamie Reed will use NHS Check to expose the reality.

I know you want us to hit them even harder – and we will.

But, Conference, I have to tell you this: it’s hard to be a Shadow when you’re up against the Invisible Man.

Hunt Jeremy – the search is on for the missing Health Secretary.

A month in the job but not a word about thousands of nursing jobs lost.

Not one word about crude rationing, older people left without essential treatment.

Not a word about moves in the South West to break national pay.

Jeremy Hunt might be happy hiding behind trees while the front-line of the NHS takes a battering.

But, Conference, for as long as I do this job, I will support front-line staff and defend national pay in the NHS to the hilt.

Lightweight Jeremy might look harmless. But don’t be conned.

This is the man who said the NHS should be replaced with an insurance system.

The man who loves the NHS so much he tried to remove the tribute to it from the Opening Ceremony of the Olympic Games.

Can you imagine the conversation with Danny Boyle?

“Danny, if you really must spell NHS with the beds, at least can we have a Virgin Health logo on the uniforms?”

Never before has the NHS been lumbered with a Secretary of State with so little belief in it.

It’s almost enough to say “come back Lansley.”

But no. He’s guilty too.

Lansley smashed it up for Hunt to sell it off with a smile.

But let me say this to you, Mr Hunt. If you promise to stop privatising the NHS, I promise never to mispronounce your name.

So, Conference, we’re the NHS’s best hope. Its only hope.

It’s counting on us.

We can’t let it down.

So let’s defend it on the ground in every community in England.

Andrew Gwynne is building an NHS Pledge with our councillors so, come May, our message will be: Labour councils, last line of defence for your NHS.

But we need to do more.

People across the political spectrum oppose NHS privatisation.

We need to reach out to them, build a new coalition for the NHS.

I want Labour at its heart, but that means saying more about what we would do.

We know working in the NHS is hard right now, when everything you care about is being pulled down around you.

I want all the staff to know you have the thanks of this Conference for what you do.

But thanks are not enough. You need hope.

To all patients and staff worried about the future, hear me today: the next Labour Government will repeal Cameron’s Act.

We will stop the sell-off, put patients before profits, restore the N in NHS.

Conference, put it on every leaflet you write. Mention it on every doorstep.

Make the next election a referendum on Cameron’s NHS betrayal.

On the man who cynically posed as a friend of the NHS to rebrand the Tories but who has sold it down the river.

In 2015, a vote for Labour will be a vote for the NHS.

Labour – the best hope of the NHS. Its only hope.

And we can save it without another structural re-organisation.

I’ve never had any objection to involving doctors in commissioning. It’s the creation of a full-blown market I can’t accept.

So I don’t need new organisations. I will simply ask those I inherit to work differently.

Not hospital against hospital or doctor against doctor.

But working together, putting patients before profits.

For that to happen, I must repeal Cameron’s market and restore the legal basis of a national, democratically-accountable, collaborative health service.

But that’s just the start.

Now I need your help to build a Labour vision for 21st century health and care, reflecting on our time in Government.

We left an NHS with the lowest-ever waiting lists, highest-ever patient satisfaction.

Conference, always take pride in that.

But where we got it wrong, let’s say so.

So while we rebuilt the crumbling, damp hospitals we inherited, providing world-class facilities for patients and staff, some PFI deals were poor value for money.

At times, care of older people simply wasn’t good enough. So we owe it to the people of Stafford to reflect carefully on the Francis report into the failure at Mid-Staffordshire Foundation NHS Trust.

And while we brought waiting lists down to record lows, with the help of the private sector, at times we let the market in too far.

Some tell me markets are the only way forward.

My answer is simple: markets deliver fragmentation; the future demands integration.

As we get older, our needs become a mix of the social, mental and physical.

But, today, we meet them through three separate, fragmented systems.

In this century of the ageing society, that won’t do.

Older people failed, struggling at home, falling between the gaps.

Families never getting the peace of mind they are looking for, being passed from pillar to post, facing an ever-increasing number of providers.

Too many older people suffering in hospital, disorientated and dehydrated.

When I shadowed a nurse at the Royal Derby, I asked her why this happens.

Her answer made an impression.

It’s not that modern nurses are callous, she said. Far from it. It’s simply that frail people in their 80s and 90s are in hospitals in ever greater numbers and the NHS front-line, designed for a different age, is in danger of being overwhelmed.

Our hospitals are simply not geared to meet people’s social or mental care needs.

They can take too much of a production-line approach, seeing the isolated problem – the stroke, the broken hip – but not the whole person behind it.

And the sadness is they are paid by how many older people they admit, not by how many they keep out.

If we don’t change that, we won’t deliver the care people need in an era when there’s less money around.

It’s not about new money.

We can get better results for people if we think of one budget, one system caring for the whole person – with councils and the NHS working closely together.

All options must be considered – including full integration of health and social care.

We don’t have all the answers. But we have the ambition. So help us build that alternative as Liz Kendall leads our health service policy review.

It means ending the care lottery and setting a clear a national entitlement to what physical, mental and social care we can afford – so people can see what’s free and what must be paid for.

It means councils developing a more ambitious vision for local people’s health: matching housing with health and care need; getting people active, less dependent on care services, by linking health with leisure and libraries; prioritising cycling and walking.

A 21st century public health policy that Diane Abbott will lead.

If we are prepared to accept changes to our hospitals, more care could be provided in the home for free for those with the greatest needs and for those reaching the end of their lives.

To the district general hospitals that are struggling, I don’t say close or privatise.

I say let’s help you develop into different organisations – moving into the community and the home meeting physical, social and mental needs.

Whole-person care – the best route to an NHS with mental health at its heart, not relegated to the fringes, but ready to help people deal with the pressure of modern living.

Imagine what a step forward this could be.

Carers today at their wits end with worry, battling the system, in future able to rely on one point of contact to look after all of their loved-one’s needs.

The older person with advanced dementia supported by one team at home, not lost on a hospital ward.

The devoted people who look after our grans and grand-dads, mums and dads, brothers and sisters – today exploited in a cut-price, minimum wage business – held in the same regard as NHS staff.

And, if we can find a better solution to paying for care, one day we might be able to replace the cruel ‘dementia taxes’ we have at the moment and build a system meeting all of a person’s needs – mental, physical, social – rooted in NHS values.

In the century of the ageing society, just imagine what a step forward that could be.

Families with peace of mind, able to work and balance the pressures of caring – the best way to help people work longer and support a productive economy in the 21st century.

True human progress of the kind only this Party can deliver.

So, in this century, let’s be as bold as Bevan was in the last.

Conference, the NHS is at a fork in the road.

Two directions: integration or fragmentation.

We have chosen our path.

Not Cameron’s fast-track to fragmentation.

But whole-person care.

A One Nation system built on NHS values, putting people before profits.

A Labour vision to give people the hope they need, to unite a new coalition for the NHS.

The NHS desperately needs a Labour win in 2015.

You, me, we are its best hope. It’s only real hope.

It won’t last another term of Cameron.

NHS.

Three letters. Not Here Soon.

The man who promised to protect it is privatising it.

The man who cut the NHS not the deficit.

Cameron. NHS Conman.

Now more than ever, it needs folk with the faith to fight for it.

You’re its best hope. It’s only hope.

You’ve kept the faith.

Now fight for it – and we will win.

Andy Burnham vows to repeal the Health and Social Care Act, and to reverse Part 3

Andy Burnham will repeal the Act, but is due to establish Labour’s official position at Conference later this week.

He answered my straightforward question about the Health and Social Care Act (2012) with a simple answer, at the Fabian Society Question Time this evening, hosted by Alison McGovern MP, and a panel also including Owen Jones, Dan Hodges, and Polly Toynbee. I had a very nice chat with Andy at the end, and Andy seemed to be quite impressed that I had read the entire Act carefully ‘from cover to cover’.

Andy reinforced his belief that the Act would be repealed, but he wanted the NHS to further a spirit of collaboration. There’s been a question about, even if the Act is repealed, there are genuine questions about which policy planks might go into reverse. I feel it is unlikely that NHS Foundation Trusts will be revised, and I don’t think commissioning will be done away with, though I am uncertain about the future of ‘clinical commissioning groups’ (“CCGs”). Andy’s indication that existing structures might be asked to do different things gives Andy a bit of lee-way as to the working relationship between NHS Foundation Trusts, or CCGs (or whatever they turn out to be).

Part 3 will be first in the firing line, the Act will be repealed, and the NHS will go back to a system based on collaboration consistent with its founding principles. Critically, this Part of the Act establishes the legislative framework for the sector-regulatory body and its functions, “Monitor”, competition and licensing. My guess is that Andy Burnham MP will find a way for the NHS not to be a free-for-all in an unfettered market. My impression is a lot depends on escaping the EU definition of “undertaking” in EU competition law.

The NHS prior to this Act had been immune from a discussion of competition in that the NHS had from this previously is that a regulatory authority for competition, the Office for Fair Trading (“OFT”) did not consider that any public bodies involved in the purchasing or supply of goods or services within the NHS were “undertakings”, and therefore were not subject to action under the Competition Act. In other words, any involvement of these bodies was for “non-economic purposes”. This was reinforced by the EU in relation to a Spanish healthcare case FENIN v Commission in 2006, on the basis that the system concerned operated on the principle of ‘solidarity’. They have therefore exposed some services (which previously would have been provided in-house) to a scenario where they will be considered for competitive tendering. The extension of Any Qualified Provider (albeit with a more limited, phased implementation from 2012) to a wider range of services, and the distancing of the state from acute sector provision in the form of foundation trusts could conceivably weaken the argument against healthcare provision being for “non-economic purposes”, particularly when individual service lines are considered.

This is highly significant, I feel, that Andy Burnham could be steering the NHS away from being run for ‘economic purposes’, and this could be the passport for Andy for not becoming enmeshed in lots of complicated domestic and EU law. As it happens, I have a real feeling that European lawyers would prefer not to enmeshed in a complicated discussion about private provision in healthcare, as they feel that competition law is best applied to pure private or commercial entities not involved in social/healthcare policy.

As it stands, the Health and Social Care Act (2012) is a complex interplay of domestic and EU law in the disciplines of company law (including mergers, financial assistance), commercial law, procurement law (including public contracts), regulatory law, insolvency law (particularly administration). However, the law, albeit at nearly 500 pages, does have some notable omissions, such as what happens if a CCG ‘trades’ while going insolvent. Law would have to clarify consider, in its capacity as a ‘body corporate’, whether the CCG were still capable of wrongful or even fraudulent trading.

An acceleration in the NHS privatisation will only hasten its disaster

The promotion of Jeremy Hunt to Secretary of State for Health marks a return of the Conservative Party to a state of permanent toxification of their Party. A ‘hard-won’ victory of David Cameron had to be to appear ‘compassionate’, and to detoxify his politics. In an issue so politically sensitive, David Cameron’s decision was bound to be ‘make or break’, and this is a decision he will inevitably regret.

The separation of the ‘induction’ and the ‘implementation’ phases by Downing Street is purely a strategic one, necessarily a cosmetic one, but substantially an illusory one. The ‘induction’ phase was an unmitigated disaster, for the reason that this was a textbook ‘how not to do a strategic change’ in management. The strategic change failed to take account of the solid foundations of the public sector ethos of the NHS public sector, and, most specifically, failed to understand the organisational culture of the NHS in terms of its key attitudes and values. The privatisation of the railways industry showed how that there was a relentless fragmentation of the implicit and explicit knowledge of that sector, meaning information and skills could no longer easily be shared, and people came disillusioned with the fragmentation. That is why it is impossible to divorce the ‘implementation’ from the ‘induction’ phase, as this strategic change does not have any support from the medical Royal Colleges or the British Medical Association.

The goal of the implementation is fundamentally at odds with the proposed mission of the people within it. Doctors, nurses and health service never undergo their protracted training to make money – there are easier ways of making money. They resent people who do not have any knowledge or wisdom about their field, making powerful decisions about how they should do their job, in much the same way that a policy director of a national charity might have no medical training but feel all potent in making policy decisions that affect the health of the nation. The private health entity has to maximise shareholder dividend by law, and Jeremy Hunt has made his views known about the NHS previously.

Hunt had also previously made his views and beliefs known about BSkyB, and it was this lack of trust which fundamentally destroyed Murdoch’s business hopes, as there was a seething sense of mistrust by the general public. Hunt has made his anti-NHS feelings known about the NHS, and Andy Burnham and Labour apparently wish to put the ‘N’ (national) back in NHS. If Jeremy Hunt seriously wishes to accelerate the speed of these ‘reforms’, this will be a guaranteed way to ensure disaster. What should have happened was for clusters of change experts to discuss the implementation of the privatisation of the NHS in small groups such that the organisational structure and culture of the NHS could gradually change, given that this was their desired mission. Inflicting this change at high speed will mean that this comes a crashing halt, and the privatisation of the NHS will result in being a massive political disaster.

The implications for David Cameron politically are massive. David Cameron failed to win the 2010 General Election, and yet has tried to embark on a privatisation of the NHS costing millions when the public cannot afford it. It does not carry with it the goodwill of the nation, and even some Conservatives are terrified about it on nostalgic grounds. It may act as a perfect sop to the ‘hard right’, but ultimately a conversion of the NHS into a neocon or neoliberal conglomerate is not a vote-winner in the long term. In fact, the reverse. Both the major parties are mistrusted on the economy, with a cigarette paper in their popularity. However, Labour is consistently ahead in terms of trust on the NHS. Jeremy Hunt is already much despised politically for his handling of press regulation and Leveson, and, while he might appear as a ‘Mr Nice Guy’, he is the perfect agent for killing the Conservative Party for a very long time indeed. Hunt has a tendency of wishing to be seen to do everything ‘by the book’, but the implementation of the privatisation of the NHS is a complex strategic change. It is not a case of presenting it in terms of excellent PR skills, on account of its fault being thus far a failure of communication (this is how people tried to explain Lansley’s failure). The strategic change requires the guts of somebody who understands business or competition law, and Hunt lacks the necessary skills or experience for this. He is the ultimate in pen-pushers, a culture that is threatening to strangle the NHS and medical charities at large.

The business model of the company, albeit in the NHS, is not in the national interest

In the new-look National Health Service, certain providers, whether they be private-limited companies or public-limited companies, will be guaranteed work from being able to charge the NHS however they wish to produce their services. They can choose to opt out of all sectors which they consider to be unprofitable, and ‘cherry pick’ what type of work it does. They are mandated by law to maximise shareholder divined.

The UK needs the structure of a National Health Service, with a clear direction about the prioritisation of clinical services at a national level. Otherwise, unprofitable health services will go insolvent and disappear from the NHS, unless the NHS is rigorously regulated.

With the progression of the new Health and Social Care Act, the horrific effect will be, unfortunately, to penalise areas of the UK where health inequalities are known to exist (for example coal miners developing emphysema or chronic obstructive airways disease through their work, or British-Bangladeshis having a high prevalence of heart attacks or strokes in Tower Hamlets through a genetic predisposition to cardiopathic traits such as hypercholesterolaemia).

We have seen precisely this problem with markets before. “Oligopolistic” markets are where there are few competitors. If an oligopolistic market then exists, the customer (or patient as he or she should be known in the NHS) may come last, as the need for shareholder primacy takes over. In gas or water, markets also privatised by the Conservatives, there is actual little competition for the consumer, prices are high, the quality of the service has not vastly improved, and shareholders have made a massive profit. Unfortunately, health is the perfect market where this deception can take place, as metrics appear in health reports, which emphasise waiting times or bed days, as the number of patients with ‘hidden’ problems, often unprofitable to treat, such as dementia or depression go unnoticed.

The real workers in the NHS are doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals, many of whom have difficulty in defining an ‘excellent outcome’ in the NHS even after a lifetime of dedicated hard work often with unbelievable stress and experience. These healthcare workers and employees need the protection of the Unions, particularly over employment rights, and need to feel valued in the NHS. It’s completely wrong if they should become merely ‘disposables’ for venture capital companies to generate a profit; the fact that reports of running roughshod over UNISON exist, and the fact that the Medical Royal Colleges have been steadfastedly opposed to the reforms, means that this is a very dangerous path for the NHS to go down.

Shibley is a member of Labour, and a member of the Socialist Health Association. He has postgraduate degrees in medicine, natural sciences, law and business.