The Government has a very confusing narrative on when it decides to use “evidence” to make policy. We all know of things appearing in Government bulletins which are simply lifted out the glossies of management consultancy firms, which is sold as advertising patter. Last week, the Government justified – irrespective of Lynton Crosby – whether “standard packaging worked”, rather than whether “standard packaging did any harm”, because that’s what the Philip Morris New Zealand copy said. This afternoon, health groups have strongly condemned the government for failing to introduce minimum unit pricing for alcohol and substituting a series of measures to curb excessive drinking that they say will not work. They warn that more lives will now be lost, but it is not the first time that this Government has ignored the views of the medical profession. The complete disregard for the views of physicians still leaves a lump in many throats of those who have had to swallow the Health and Social Care Act (2012). Now, many are breathing in the latest Government toxic policy on public health, but trying desperately hard not to inhale. The Alcohol Health Alliance (AHA), which includes medical royal colleges and specialist doctors as well as campaigners, accused the government of buckling to pressure from the drink industry, which has fiercely opposed minimum pricing – a measure which is supported by doctors, children’s charities, pub landlords and the police.

I must admit that I have a conflict of interest, but I don’t think this makes me look at this issue particularly emotionally. I know that I am alcoholic, but I am one in remission. I have been in recovery for over six years. I think alcoholism is a good example of where the medical profession does not have all the answers, though the side effects of alcohol misuse affects every bodily system under the sun (for example peripheral neuropathy or gastritis.) It turns out that drug prescriptions to treat alcohol dependency in England has increased by almost 75 per cent in nine years, a health watchdog has warned. Almost 180,000 prescriptions were given to patients dependent on alcohol in 2012 compared to 102,740 in 2003, which, according to the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC), is the highest number ever recorded. HSCIC Chief Executive Alan Perkins said today’s report illustrates the impact of alcohol misuse on hospitals in England. The report ‘Statistics on Alcohol: England, 2013’ shows 315 prescription items were dispensed per 100,000 of the population in 2012 compared to 203 per 100,000 in the previous year. Dr Nick Sheron, Royal College of Physicians advisor on alcohol, said “The rise in prescriptions of drugs to treat alcohol dependency is indicative of the huge strain alcohol abuse puts on our society.” “The rise in alcohol addiction is being driven by cheap alcohol. A minimum unit price for alcohol would effectively tackle this problem.”

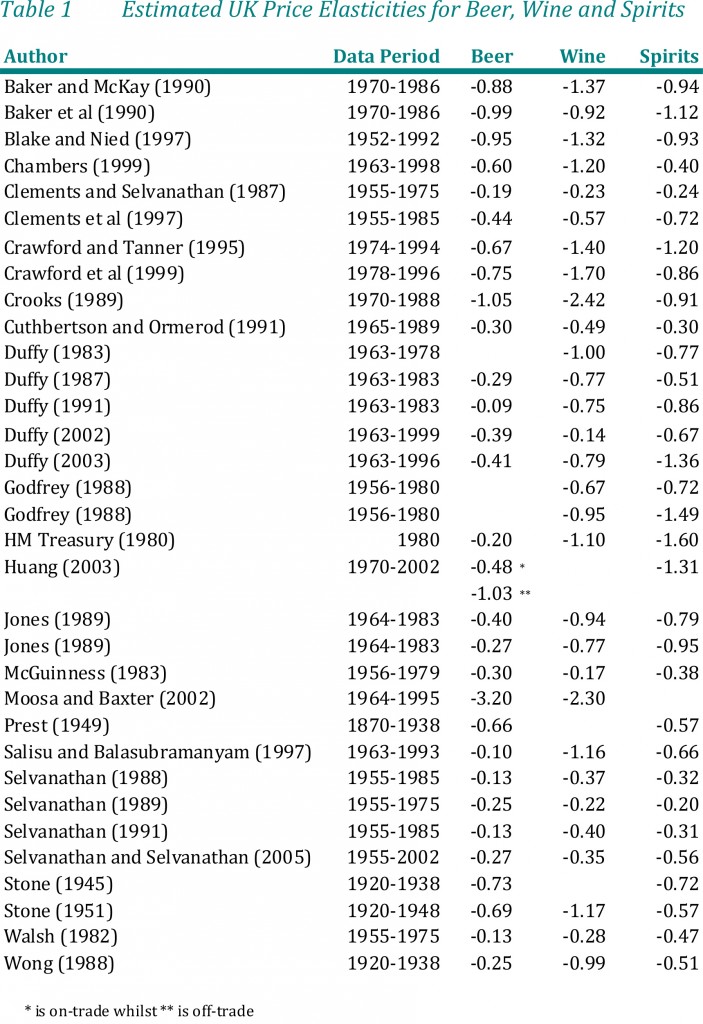

One of the many strands in this vital policy debate is whether citizens give a damn about the price of alcohol. One could argue that hardcore alcoholics like I was once don’t really care about the price of alcohol, because by that stage an alcoholic with severe dependence is not drinking alcohol for enjoyment, but to avoid withdrawal symptoms as a drug. A HRMC document entitled “Econometric Analysis of Alcohol Consumption in the UK” described that the demand for alcohol is influenced by a greater set of factors than many other consumption goods. The factors in the mix are intriguing, and also have a part to play in alcohol policy taken as a whole. As well as price and income, alcohol consumption is influenced by licensing restrictions, taxation, advertising restrictions, minimum age requirements, social factors, peer group pressure, habit formation, underlying health concerns, location, sex, age, religion, marital status, and so on. Cross?section analysis, as used in this study, is able to capture and control for this level of diversity. There is fairly conclusive and longstanding evidence that price has a negative impact on alcohol consumption in the UK. From this Table, one can also see that the general pattern is that beer is the most inelastic of the three main alcohol products.

Placing a minimum price on a unit of alcohol delivers health benefits much greater than those predicted by the UK government’s theoretical model, concluded a report by the independent UK Institute of Alcohol Studies recently, which decided to use empirical data from Canada, where minimum pricing has been in place for decades (Stockwell and Thomas, 2013). Official estimates of about 9000 alcohol related deaths annually are low as they exclude 4600 deaths from alcohol-related cancer and a wide range of alcohol-related injuries. UK alcohol consumption has risen in the last three decades, and is now 80% above the global average. More than half the alcohol sold in the UK is consumed above recommended daily limits. Alcohol is 45% more affordable than in 1980 and both men and women can exceed recommended daily limits for about /£1 if they purchase inexpensive alcohol from supermarkets or other outlets. The authors cited criticism of the Sheffield and Canadian research, much of it from commercial vested interest groups, has been inaccurate and misleading

It is interesting if one takes a comparative approach to alcohol policy. Most Canadian provinces have long exercised some form of government control over the distribution of alcohol through a mixture of government owned and privately owned outlets. Most provinces set minimum prices on a litre of wine, beer, and spirits. One province, Saskatchewan, adjusts minimum prices within drink categories according to alcohol content. The UK government has used the Sheffield alcohol policy model to predict effects of minimum unit pricing on consumption, health, and public revenue. In British Columbia the Sheffield model estimated that a minimum price per unit of $C1.50 (£1; €1.1; $US1.5) for all alcoholic drinks would reduce the number of wholly alcohol caused deaths (a category that includes alcohol poisoning but not cirrhosis) by 39 and the number of hospitalisations by 244 in the first year, with additional health benefits 10 years later.

However, the Institute of Alcohol Studies’ report cites studies published in Addiction and the American Journal of Public Health which found that a $C1.45 minimum price resulted in an estimated reduction of 92 wholly alcohol caused deaths and 1212 hospitalisations in the first year, with additional health benefits in chronic disease seen two years later (Zhao et al., 2013, Stockwell et al., 2013). Increases in the minimum price of alcohol in British Columbia, Canada, between 2002 and 2009 were associated with immediate and delayed decreases in alcohol-attributable mortality. By contrast, increases in the density of private liquor stores were associated with increases in alcohol-attributable mortality (Stockwell et al., 2013). A Can $0.10 increase in average minimum price would prevent 166 acute admissions in the 1st year and 275 chronic admissions 2 years later, it was further hypothesised. The authors estimated significant, though smaller, adverse impacts of increased private liquor store density on hospital admission rates for all types of alcohol-attributable admissions (Zhao et al., 2013).

The Institute’s own report cites evidence that heavy and problem drinkers are far more likely to seek out cheap alcohol and thus to be affected by a minimum price. Katherine Brown, the institute’s director of policy, said that the report would “give policy makers confidence that fulfilling the commitment to introduce this measure in the UK will deliver significant health and social benefits without unfairly penalising moderate drinkers or those on low incomes. The report comes as Scotland’s Court of Session struck down a challenge by the Scotch Whisky Association to the Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012, which sets a 50p minimum price on a unit of alcohol (Christie et al., 2013). This meant that Scotland became the first place in the UK to introduce minimum drink pricing, after MSPs passed new laws. Under the plans, it was envisaged that the cheapest bottle of wine would be £4.69 and a four-pack of lager would cost at least £3.52. The move had won broad political backing, although Labour refused to support the legislation at the Scottish Parliament. The Alcohol Minimum Pricing Act, which aims to help tackle drink-fuelled violence and associated health problems, cleared its final parliamentary hurdle when MSPs backed it by 86 votes to one, with 32 abstentions. In a landmark ruling applauded by medical groups, a court has judged Scotland’s proposal to set a minimum price on a unit of alcohol as legal and compatible with European law. However, the Scotch Whisky Association and the trade organisation Spirits Europe, which have challenged the legality of minimum pricing, intended to appeal and were confident of success.

One suspects that this story is not over, yet, irrespective of the Government’s obvious turmoil over lobbying.

References

Christie B. Minimum alcohol price is compatible with EU law, says Scottish court. BMJ 2013;346:f2925.

Stockwell T, Thomas G. Is alcohol too cheap in the UK? Setting the case for a minimum unit price for alcohol. Apr 2013. http://www.ias.org.uk/uploads/pdf/News%20stories/iasreport-thomas-stockwell-april2013.pdf

Stockwell T, Zhao J, Martin G, Macdonald S, Valance K, Treno A, et al. Minimum alcohol prices and outlet densities in British Columbia, Canada: estimated impacts on alcohol attributable hospital admissions. Am J Public Health. Published online ahead of print April 18, 2013: e1–e7.

Stockwell T, Zhao J, Giesbrecht N, Macdonald S, Thomas G, Wettlaufer A. The raising of minimum alcohol prices in Saskatchewan, Canada: impacts on consumption and implications for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012 Dec;102(12):e103-10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301094. Epub 2012 Oct 18.

Zhao J, Stockwell T, Martin G, Macdonald S, Valance K, Treno A, et al. The relationship between changes to minimum alcohol price, outlet densities and alcohol-related death in British Columbia, 2002-2009. Addiction, Volume 108, Issue 6, pages 1059–106.

Pingback: Minimum pricing of alcohol: what's the fuss? - ...()