Home » Substance abuse

My experience of being a sick Doctor

“Anything can happen to anybody at any time.”

This one principle does guide what I think about people and health.

It’s what I think when a friend of mine living with dementia suffers a bereavement. It’s what I think when a friend of mine gets told he has bladder cancer.

It’s also how I come to rationalise my six week coma in 2007 due to acute bacterial meningitis. I was rushed into the intensive care unit of the Royal Free Hospital Hampstead, having been resuscitated successfully by somebody I used to work with in fact. He knows who he is.

His team stopped me fitting in an epileptic seizure. His crash team got a pulse back on their third cycle of jumping down on my chest after I had been flatlining in cardiac asystole. He managed to put a tube down me as I had stopped breathing.

I then spent six weeks in a coma, and my mother and late father came to visit me every day in intensive care, and in the neurorehabilitation unit (Albany Ward) at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London (a hospital in which I had worked in 2002 in a rotation which included an interest of mine, dementia).

I am now living with physical disability. I can now walk, and I remember my protracted time in a wheelchair. I remember people’s reactions to you in the street. I remember how ‘available’ black cabs would simply drive past. I was, in effect, taught how to work again by inpatient and community physiotherapy.

Due to my meningitis, I could barely speak; the “speechies” helped me with that. I had difficulty planning a cup of tea; the “OTs” helped me with that.

I can relate to all the current NHS concerns how you become stripped of identity in the modern NHS: you become a bed number, or at best a surname.

But in many ways, as my late father kept reminding me shortly before his own death in November 2010, that meningitis in a way saved my life.

I then engaged properly with the NHS as a patient. I used to see my GP regularly.

As a medical student, I had felt as if I was too busy to see my own GP. Big mistake.

As a young house officer in hepatology, I used to be surrounded with very pleasant patients; but for whom I had to perform an abdominal paracentesis, as they were often bright yellow due to liver failure (but awaiting a liver transplantation).

I slowly became alcoholic and isolated. I have often been asked when did I start to drink heavily. This is very difficult for me to place, as most people like me go through a phase of problem drinking.

My official diagnosis for the alcoholism is severe alcohol dependence syndrome in remission. I have now not drunk alcohol for seven years. I know I am an alcoholic as it is unsafe for me to have an alcoholic drink. If I have an alcoholic drink, I would either end up in A&E or in a police cell. I am incapable of having a social drink.

Receiving a medical diagnosis for my mental health condition, in my particular case, helped me to rationalise the cause of my problems which had caused so much distress to others including especially my mother and late father.

I was listening to LBC last night and the presenter was joking that he had a listener rung up “I am an alcoholic. I haven’t had a drink for 35 years.” But seriously folks, it is like that.

I am now regulated by the legal profession. I spent 9 years at medical school, doing my basic degrees for medicine and surgery, and my PhD in the early diagnosis of frontal dementia. As a junior in the medical profession, walking around as the most junior member pushing the Consultant’s trolley and writing in the notes, the thought that you might be ill did seem an alien one.

And yet I was extremely ill. For all people in addiction, there becomes a time when you are in complete denial and lack complete insight. That’s when it is impossible for you to be regulated.

I also have a lot of sympathy for the regulators who regulate people who I think can be best be described as a “dry drunk patients” – i.e. they spend months or even years dry before relapsing. They are, I feel, “living by the seat of their pants”, or “whiteknuckling” it.

The alternative is recovery – where you are not merely abstinent, but where you embrace a life which is utterly content, but in the absence of your addiction of choice.

I indeed find this hard to explain to people who have never experienced addiction. I do not wish to compete with ‘patient leaders’, or think tanks who go on and on and on and on about patient involvement.

But I do wish to recommend to you, if you are in their catchment area, the Practitioners Health Programme (PHP). An incredible ambition of Prof Clare Gerada, the programme is a lifeline to doctors who are ill. It’s been shown in numerous numerous surveys that an ill doctor under-functions as much ‘use’ as a doctor who is completely out of the service. I would simply say to anyone who is ill in the medical profession, put your own health ahead of your career. Your patients deserve that too. Do not be blinded by your own career. I am proud to attend regularly PHP.

I don’t do much apart from hundreds of blogs for the SHA, or campaigning for people living with dementia. But I am at least at last content.

Update: I (Dr Shibley Rahman) was returned to the GMC Register for the UK 26 August 2014. I had been in recovery from alcohol since the onset of my coma due to meningitis in June 2007.

Should e-cigarettes be available on the NHS?

Addicts are great customers, they have a huge appetite for your product and they keep coming back.

Addicts are great customers, they have a huge appetite for your product and they keep coming back.

That of course is the market-driven view of public health. A coherent national public health policy should consider the evidential impact of measures on the health of its citizens.

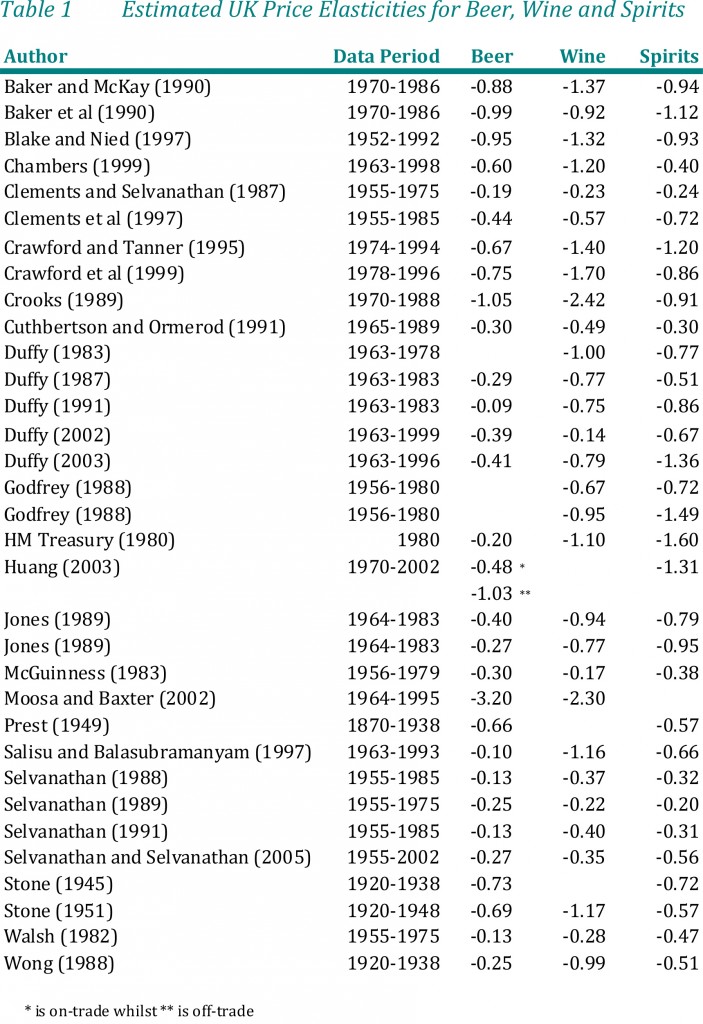

The last few years have indeed seen a public health which appears to have been somewhat determined by the phenomenon of ‘corporate capture’, such as the interests of corporates rather than public health physicians. This is of course partly a reflection of the current government in office, and spans across a growing number of policies including obesity, packaging of cigarettes, and pricing of alcohol.

A buzzword in management circles has been ‘disruption‘. It is felt that early digital cameras suffered from low picture quality and resolution and long shutter lag. Quality and resolution are no longer major issues and shutter lag is much less than it used to be. The convenience and low cost of small memory cards and portable hard drives that hold hundreds or thousands of pictures, as well as the lack of the need to develop these pictures, also contributed to the successful adoption of these disruptive technologies. Digital cameras have a high power consumption (but several lightweight battery packs can provide enough power for thousands of pictures).

According to Wikipedia, a disruptive innovation “is an innovation that helps create a new market and value network, and eventually goes on to disrupt an existing market and value network, displacing an earlier technology”. It is a term used to describe changes that improve a product or service in ways that the market does not expect.

Disruptive technologies have created new industries and new markets. They have also rendered others obsolete and outdated. They provided consumers with something they did not know they wanted. The economist Joseph Schumpeter referred to this process as “creative destruction.” Early investors in these companies certainly took on a lot of risk. There was no way to know whether or not an idea would be profitable. After all, these ideas had no track record.

The American investment banking firm Goldman Sachs earlier this year released a list of eight disruptive themes that have the potential to reshape their categories and command greater investor attention in the near future. Electronic cigarettes were listed as one of these eight markets investors should keep an eye on, for their potential to transform the tobacco industry.

As described in “E Cigarette Forum”,

The little vaping companies that make alternative devices may not make it into the fortune 500 or onto the boards of the NYSE, but they will survive because they have a passionate clientele. They’re like the little mammals that scurried around the massive feet of the dinosaurs at the end of the Jurassic, 65 million years ago, just as the big guys were about to go belly up. Bet on the little guys. They’ll survive.

On October 8th 2013, the European Parliament is to vote on a proposal to regulate the devices as if they were medical products. E-cigarettes (“e-cigs”), which allow users to inhale nicotine-laced vapour instead of tar-clogged smoke, are a growing market, set to top $1bn in the next three years. Smoking is falling in most rich countries, but “vaping” is rising. In Europe, 7m people are thought to be using e-cigs, which vaporise a solution containing nicotine without the toxins from burning tobacco. Sales of e-cigs in America may treble this year, according to figures from Bonnie Herzog of Wells Fargo, a bank. She thinks their consumption could overtake that of ordinary cigarettes in a decade.

An “e-cig” is composed of a mouthpiece, a liquid nicotine cartridge, a heating element and a battery. When the user inhales on the e-cig, the heating element is activated. The liquid nicotine cartridge is heated and creates a vapor. This is what the user inhales. It is odourless. It doesn’t contain any of the other chemicals or tar found in traditional cigarettes.

E-cigs may be far safer than normal cigarettes and at least as good at getting people to quit smoking as nicotine patches and gum, but they too are based on that addictive substance. Manufactured by hundreds of suppliers using materials from China and elsewhere, the quality and labelling of e-cigs on sale are known to be uneven.

E-cigs can be smoked indoors. Once again, there are no noted effects of secondhand vapour. The vapour that is exhaled has little to no odour. Bar and club owners may even be becoming fans of e-cigs. Users who buy them are more likely to stay in the bar and consume more drinks than they otherwise would. This may add to the ‘coolness’ and convenience factor of these disruptive new products. There are a number of possible suggested benefits.

There is a noted reduction in side effects commonly reported by smokers. Some of these side effects are shortness of breath, dry mouth and headaches. Along with reduction of side effects, there is no secondhand smoke. The vapour that the user exhales quickly vanishes and does not appear to cause harm to bystanders.

A ‘quick reference guide’ for ‘smoking cessation services’, from NICE, published in February 2008 gives an overview of what was perceived then could or should be offered on the NHS to help people give up smoking. This evidence-based guidance presents the recommendations made in ‘Smoking cessation services in primary care, pharmacies, local authorities and workplaces, particularly for manual working groups, pregnant women and hard to reach communities’. It provides a rationale for who could provide smoking cessation services (as it predates the £3bn top-down reorganisation, it refers to a critical rôle for PCTs and SHAs), what pharmacotherapies might be prescribed and for whom (and where they should not be prescribed), which patient groups might be beneficially targeted, and how effectively educational and training resources might be allocated.

It is no secret that despite public health efforts the popularity of electronic cigarettes has increased at a rapid pace in recent years. E-cig sales have doubled in the last two years and they are estimated to reach $1billion in retail sales in 2013. According to a Gallup poll, 74% of smokers want to quit, and Goldman Sachs analysts believe the electronic cigarette is “the most credible alternative to conventional cigarettes in the market today”.

This investment giant estimates electronic cigarettes could reach $10 billion in sales over the next few years and account for over 10% of the total tobacco industry volume and 15% of the total profit pool by 2020. In April 2012, one of the big cigarette companies threw its hat in the ring. This was Lorillard, maker of Newport and other cigarette brands. They spent $135 million on the purchase of blu e-cigs. They’ve seen a lot of success with the brand. Sales have grown from $8 million in in the second quarter of 2012 to $57 million in the second quarter 2013. This is a gain of more than 600%. Lorillard claims they hold around 40% of the total e-cig market share. So of course Big Tobacco is eager to get in on the act, and as Hargreaves notes, cigarette manufacturers Lorillard, Reynolds American, Imperial Tobacco, British American Tobacco, and Altria are all bringing out e-cigs, along with newer companies like Vapor and privately-held NJOY.

There are, of course, risks to this growth. One realistic threat is the tightening of the manufacturing and product standards, or bring in a specific set of rules rather like those governing cosmetics. However, any government would have to be motivated to do this, and, following evidence for ‘corporate capture’ in English policy since the election of the UK Coalition government in 2010, e-cigs are likely to experience an ‘easy ride’.

But there are other considerations. Electric smokes compete with cigarettes yet do not in most places face the same restrictions, to say nothing of excise taxes. They compete with smoking-cessation products yet do not usually have to secure prior approval for products or make them to pharmaceutical standards. If they are required to do either, their price will rise, variety will fall and the uptake by consumers, who are overwhelmingly smokers, will be cut.

Furthermore, the World Health Organisation does not encourage them. America’s Food and Drug Administration is expected to propose restrictions in October. In 2009 it claimed that e-cigarettes were unapproved medical products, but a court said they should be regulated as tobacco products instead. Health authorities worldwide are struggling to deal with this new way of getting a nicotine kick. E-cigarettes are sold as leisure products and as such are covered by safety and quality standards wherever these exist and are implemented. But leaving them, like shoes or beds, to such “catch-all rules” makes some regulators uneasy. The most obvious is the involvement of the FDA. E-cig companies are anticipating that the FDA will get more heavily involved in regulating the e-cig market. This is a known risk currently being priced into e-cig dividends.

If, conversely, FDA regulation is passed, this could actually help their stock price. It would grant a degree of certainty in the minds of investors. It could also have the effect of crowding out some of the smaller players. It may also have the effect of boosting consumer confidence in the e-cigarettes. E-cigarettes, which allow users to inhale nicotine-laced vapour rather than tar-clogged smoke, are a growing market (expected to top $1billion in the next three years) but some countries including Brazil, Norway and Singapore have already banned the devices. The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) have already announced that e-cigarettes will be regulated in the UK as a non-prescription medicine. In the US, the FDA has previously warned makers for violating good manufacturing practices and making unsubstantiated drug claims.

The goal, according to Clive Bates, a former director of Action on Smoking and Health, a British campaigning group, and a tireless advocate of e-cigarettes, is not to lose the chance of millions of smokers switching in whole or in part to a relatively benign alternative. “The market is producing, at no cost to the taxpayer, an emerging triumph of public health,” he says.

In terms of the market economy, regarding the way Big Tobacco will be affected by the evolution of electronic cigarettes, Goldman Sachs predicts Lorillard will be the biggest beneficiary of the shift. after its acquisition of Blu ecigs. Blu commands 40% of e-cigarette market share and and it is expected its sales will account for 5% of Lorillard’s overall sales this year. Having a dominant e-cig brand in its portfolio puts the company in a favorable position, and could be included in even the most ‘ethical’ of pension funds in an investment portfolio.

However, perhaps the biggest threat to public health might be the market philosophy, which the current Coalition of the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats appear to be sympathetic towards. As the Conservative Party begin their annual party conference in Manchester, it is possibly worth noting the criticism of Dr Clive Peedell, Co-Chair of the National Health Action Party, of an article by Nigel Edwards in Health Services Journal.

Peedell described that,

“In addition, market theory in the form of public choice theory rejects the idea of medical professionalism and the public service ethos. James Buchanon, “the father” of this theory admitted in a BBC documentary (“The Trap”, by Adam Curtis) that he didn’t believe in the concept of the public service ethos. Julian Le Grand famously used the “Knights and Knaves” metaphor to explain this. The solution to “rent seeking behaviour” is the discipline of the market. This would turn “pawns in queens”. The introduction of the market also explains the rise of New Public Management (managerialism), which favours narrow economic priorities and micro-management practices (e.g audit, inspection, performance indicators, league tables, monitoring and centrally imposed targets) over professional judgment [6]. (I was politicised by MMC, by the way, because I rejected its anti-professional tick box aims. It was about delivering a new breed of doctor to suit the needs of employers in the new healthcare market). And there’s more! (as Frank Carson used to say). Markets undermine the social contract between doctors and patients and damage the doctor patient relationship, because decision making becomes increasingly finance based rather than needs based. It is no coincidence that the American medical profession lost public support faster than any other profession during the rapid commercialisation of the US healthcare system in the 1970/80s.”

Libertarians might argue that citizens individually are ‘free’ to make their own choices, in the same way that ‘fat people may choose to become fatter’ due to lack of self-restraint on food. However, such crass stupidity ignores the sheer biology of how some human beings control their intake. Indeed, the first rule of recovery in substance abuse and misuse clinics in the ‘Twelve Steps’ program is for the addict to admit “powerless” over their drug of choice. Ultimately, like many of these decisions, it will come down to a cost-benefit analysis, but such sums are notoriously difficult. How much money should the NHS spend ‘from hard-working taxpayers’ money’ on such treatments, when people ‘choose to smoke’ or ‘choose to become fat’ in the rather prejudiced jaded view of the health of others? Some people might prefer this health responsibility to be offloaded who can exploit maximal rent-seeking behaviour in making a profit, in much the same way that the ‘first mover advantage’ of any Big Pharma that unlocks the secret to NHS ‘Big Data’ might become a multi-billionaire.

Deciding on the health benefits of the e-cig would have been a difficult enough job. Pile on this the consideration of this Government which knows where its priorities lie, the terrain is even more uncertain possibly.

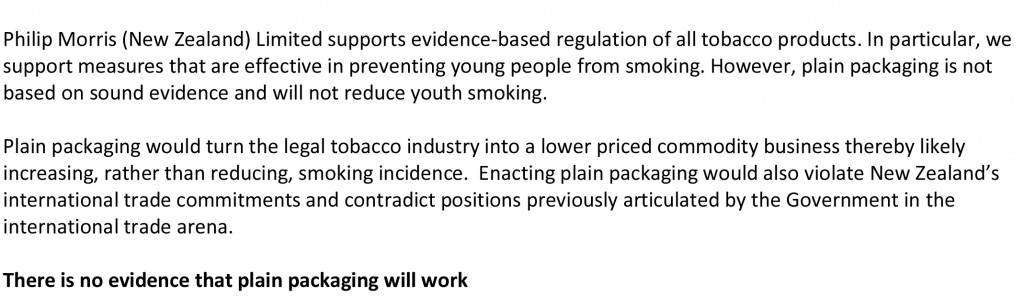

Government statement on consultation on standardised packaging of cigarettes

Links:

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/consultation-on-standardised-packaging-of-tobacco-products

https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/standardised-packaging-of-tobacco-products

The summary report of the responses to the public consultation on standardised packaging of cigarettes has recently been published by the Department of Health. There were more than 668,000 responses to the consultation. The opinions were highly polarised with strong views put forward on both sides of the debate. There was also widespread use of campaigns and petitions by a number of organisations. Having carefully considered these differing views, the Government has decided to wait until the emerging impact of the decision in Australia can be measured before making a final decision on this policy. Currently, only Australia has introduced standardised packaging, although the Governments of New Zealand and the Republic of Ireland have committed to introduce similar policies. Standardised packaging, therefore, remains a policy under consideration.

Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt said:

The UK is known the world over for its comprehensive, evidence-based tobacco control strategy, and we are continually driving down smoking rates through our range of actions.

Obviously we take very seriously the potential for standardised packaging to reduce smoking rates, but in light of the differing views, we have decided to wait until the emerging impact of the decision in Australia can be measured, and then we will make a decision in England.

This decision is an important one and whilst we keep it under review, we’ll be continuing to implement our existing plan to reduce smoking rates through ending the display of tobacco in all shops, running national behaviour change campaigns to encourage smokers to quit and through supporting local authorities to provide effective stop smoking services.

Many decisions are subconscious. That’s what marketing people manipulate to make loadsamoney.

It is actually very hard to tell whether this Government’s actions are a result of a fundamentally libertarian ideology, or whether there is simply no ideology at all – they simply wish to allow their “corporate friends” to make lots of money (which as such is not an ideology). The screw-up over plain packaging in cigarettes can be interpreted at a number of different levels. One is how plausible transparency in the Government is: whilst the evidence concerning Lynton Crosby himself (and his company) is unconvincing, the lengths that international tobacco companies might go through in influencing public health policy are interesting. It could be argued that tobacco companies are simply not keen on regulation, but that does not stop Philip Morris initiating legal action at the drop of the hat. There are wider subtler inherent contraindications in the analysis of the power of the State and its rôle in public health too which will cause problems ultimately. A strong undercurrent has been the notion of “choice”, typified by Tim Kelsey’s approach to the use of data in decision-making of patients, or “customers of the NHS” as called by some. The idea that “regulation is bad” is of course fully consistent with a political philosophy from the Conservative Party, and while the Labour Party could rightly be accused of a somewhat authoritarian, “nanny state” tinge to its last attempt at office and power, the idea of the “public good” continues to gather much support in many jurisdictions.

The government has actually now mutualised its “Nudge” unit, but “Nudge” was the future once. The centrality of using behavioural insights to the Coalition government is such that it entered formal written agreement between the Conservative and Liberal parties, in the foreword by the two party leaders and their juniors:

“There has been the assumption that central government can only change people’s behaviour through rules and regulations. Our government will be a much smarter one, shunning the bureaucratic levers of the past and finding intelligent ways to encourage support and enable people to make better choices for themselves”.

Nudge is an interesting foray into consumer behaviour, and part of the problem in this is that human beings are often irrational (and certainly will make suboptimal decisions on the basis of dodgy data.) Consumer behaviour is ultimately determined by cognitive processes, such as perception, selective attention, and memory, which is why the approach to “big data” fails inherently to capture individual differences. This is a problem in planning public policy, but why should the field of marketing and economics be so interested in packaging if it does not matter? The actual evidence provides that product packaging is an important tool for suppliers to communicate with consumers.1 Tobacco manufacturers have effectively used cigarette pack design, colours, and descriptive terms to communicate the impression of lower tar or milder smoke while preserving taste “satisfaction”. Smokers’ beliefs about a given product are likely to be shaped in part by the descriptors, colours, and images portrayed on the pack and in related marketing materials.

In the US jurisdiction, “The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control” (Article 11) calls for a ban on misleading descriptors in an effort to address consumer misperceptions about tobacco products. New regulations contained in the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 (FSPTCA) prohibit tobacco companies from labelling cigarette packs with terms such as light, mild, or low after June 2010. However, experience from countries that have removed these descriptors suggests that cigarette marketers manage to circumvent the intended goal of the regulation by using different terms, colours, or numbers to communicate the same messages. Specifically, recent research has shown that consumers in the United Kingdom and Canada, which have removed “light” and “mild” descriptors, perceive cigarettes in packs with lighter colours as less harmful and easier to quit compared to cigarettes in packs with darker colours. Colour is a good example of non-verbal marketing signal, which has an important influence on our daily lives. The underlying emotions that colours evoke have been cultivated since birth and vary depending on age, geographic location, and gender (e.g. blue for boys, pink for girls). Colour, it affects, affects our moods and feelings, and research suggests that it has a physical effect as well, influencing the hormones that control our emotions.

Studies have shown that color:

- Increases brand recognition by up to 80%

- Improves readership as much as 40%

- Increases comprehension by 73%

- Can be up to 85% of the reason people decide to buy

Bansal-Travers, O’Connor, Fix,and Cummings (Am J Prev Med 2011;40(6):683–689) showed 193 participants array of six cigarette packages (altered to remove all descriptive terms) and asked to link package images with their corresponding descriptive terms. Participants were then asked to identify which pack in the array they would choose if they were concerned with health, tar, nicotine, image, and taste. Participants were more accurate in matching descriptors to pack images for Marlboro brand cigarettes than for unfamiliar Peter Jackson brand (sold in Australia). Smokers overwhelmingly chose the “whitest” pack if they were concerned about health, tar, and nicotine. Smokers in the U.S. associate brand descriptors with colours. Further, white packaging appeared to most influence perceptions of safety.

Tobacco studies indicate that health-related information in cigarette advertising leads consumers to underestimate the detrimental health effects of smoking and contributes to their smoking-related perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes. Paek and colleagues (Paek et al., 2010) examined the frequencies and kinds of implicit health information in cigarette advertising across five distinct smoking eras covering the years 1954-2003. Most notably, a majority of the cigarette ads portrayed models smoking, lighting, or offering a cigarette to others. Rooke and colleagues (Rooke et al., 2010) investigated how tobacco displays are used at the point of sale (PoS) as an important means for the tobacco industry to communicate with consumers. With regulations prohibiting PoS displays recently having come into force in Ireland, this is an increasingly important issue. Over 100 retailers were visited, with interviews taking place on site. Information was gathered on the type and size of tobacco display, who was paying for the display, requirements and incentives, and visits by industry representatives. The majority of retailers had gantries provided by tobacco companies. A minority of these were fitted with automated dispensers called retail vending machines. Attractive lighting and colour were often used to highlight particular products. Wakefield and colleagues (Wakefield et al., 2002) investigated the role of pack design in tobacco marketing. A search of tobacco company document sites using a list of specified search terms was undertaken during November 2000 to July 2001. Many smokers are misled by pack design into thinking that cigarettes may be “safer”. There is a need to consider regulation of cigarette packaging.

The World Health Organization applauded Australia’s law on plain packaging noting that “the legislation sets a new global standard for the control of a product that accounts for nearly 6 million deaths each year” The Cancer Council of Australia hailed the passing of the legislation, stating, “Documents obtained from the tobacco industry show how much the tobacco companies rely on pack design to attract new smokers….You only have to look at how desperate the tobacco companies are to stop plain packaging, for confirmation that pack design is seen as critical to sales.” Don Rothwell, professor of international law at the Australian National University, noted that Philip Morris was pursuing multiple legal avenues. The Notice of Arbitration under the bilateral investment treaty between Hong Kong and Australia has a 90-day cooling off period after which the case would most likely be sent to the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes in Washington. He stated that Philip Morris was most likely aiming for the Australian Government to back down, or failing that, to sue for compensation. He said the questions to decide are whether the legislation means that Australia would acquire property by the imposition of these rules and if this legislation is a legitimate public-health measure. Gavin Allen of the Daily Mail newspaper reported that the Philip Morris lawsuit could cost the Australian government “billions”. He also noted that the Australian law is being closely watched by other governments in Europe, Canada and New Zealand. In 2005, the World Health Organization urged countries to consider plain packaging, and noted that Bhutan had banned the sale of tobacco earlier in 2011.

As the latest row over the role of big money in politics hit Downing Street, Paul Burstow, who was a health minister until September last year, said Crosby should either quit or be sacked by Cameron after it emerged that his lobbying firm works for global tobacco giant Philip Morris. Other Liberal Democrats also made clear they were furious and would fight to ensure Crosby was removed from any role in which he could influence health or any other coalition policy. Amid the growing furore, the Tory chairman of the all-party select committee on health, former health secretary Stephen Dorrell, announced that his committee would look into why the government had changed its mind on the question of cigarette packaging.

This is a very serious issue. The Observer editorial was devoted to it this morning.

As the Smokefree Action Coalition points out, cigarettes are the only legal product sold in the UK that kill their consumers when used exactly as the manufacturer intends. Even if the government remains unconvinced of the wisdom of plain packaging, an alliance of MPs, charities and health experts and the Faculty of Public Health disagree, as does the public. A YouGov poll in February found that 64% of the public is also in favour. So why the sudden U-turn?

The tobacco giants are spending £2m in a campaign against standardised packaging. Critics also point out that the industry has its very own Trojan horse inside Number 10, in the shape of Australian Lynton Crosby, the Conservatives’ general election co-ordinator. Hours after the decision to postpone plain packaging, it emerged that Crosby’s company, CTF, has been advising Philip Morris Ltd in Britain since November. Now there are calls for an inquiry. As the lacklustre bill on lobbying moves through parliament, Deborah Arnott, chief executive of the health charity Action on Smoking and Health, rightly says: “David Cameron has called political lobbying the ‘next big scandal waiting to happen’. Happen it has, right in 10 Downing Street.” Tory MP and GP Dr Sarah Wollaston, who also campaigns for price controls on alcohol, aptly tweeted: “RIP public health. A day of shame for this government; the only winners big tobacco, big alcohol and big undertakers.”

“There is another fundamental contradiction in nudging, particularly in the context of the declared intent to increase a sense of individual responsibility outlined by the Prime Minister. Whilst there may be an attempt to provide at least token interference transparency to preserve the possibility of exposing a ‘nudge too far’, this also underlines how far this process is from one that encourages greater learning about problems and how the individual might take on some responsibility for their management. Behaviouralism directs us away from building the renewed sense of personal and social responsibility the Coalition government has set out as fundamental to its mission.”

Therein lies the rub perhaps. While promoting “individual choice” through nudges, the policy has inadvertently discouraged personal responsibility, and especially responsibility for other members of the community. The critical problem is that the whole is not the sum of its constituent parts, and while FA Hayek’s “The Road to Serfdom” was hailed by Margaret Thatcher (whose remark was passionately argued by the Bishop of London at her funeral to have been misquoted), cognitive neuroscience acknowledges that individuals often make the “wrong” choices – wrong for them individually, and also wrong for society. Many decisions are unconscious, and indeed that is what the whole of the profit-generating marketing industry is devoted to manipulating. But the fact that these decisions are unconscious tells you exactly what is fundamentally incorrect about the libertarian analysis. People don’t know why they’re making certain decisions: they are not in control at all. The advertisers are. And more importantly, they cannot learn from their decision-making process. Public health, for all its possible faults, is firmly against this philosophy.

References

Paek HJ, Reid LN, Choi H, Jeong HJ. (2010) Promoting health (implicitly)? A longitudinal content analysis of implicit health information in cigarette advertising, 1954-2003. J Health Commun. 2010 Oct;15(7):769-87. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.514033.

Rooke C, Cheeseman H, Dockrell M, Millward D, Sandford A. Tobacco point-of-sale displays in England: a snapshot survey of current practices. Tob Control. 2010 Aug;19(4):279-84. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.034447. Epub 2010 May 14.

Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK, Cummings KM. (2002) The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. Mar;11 Suppl 1:I73-80.

Bansal-Travers, M, O’Connor, R, Fix, BV, Cummings, KM (2011) What Do Cigarette Pack Colors Communicate to Smokers in the U.S.? Am J Prev Med 2011;40(6):683– 689

If I could predict the future of my health, would I change my behaviour?

A major issue in economics certainly is how individuals cope with information. Much information is uncertain, so one’s ability to make rational decisions based on irrational information is a fascinating one. Predicting the future may be viewed as best kept as the bastion of astrologers such as Mystic Meg, but the likelihood of future outcomes is clearly of interest in the insurance industry. These decisions are not only helpful for people at an individual basis, but also hopefully useful for planning, rather than predicting, what is best for the population at large in future.

Angelina Jolie did not have cancer, but, in fact, like many women with breast cancer mutations, she had the radical surgery to lower her risk. She, at the age of 37, has described her decision as “My Medical Choice,” in an op-ed in the New York Times. She carries the BRCA1 gene mutation, which gives her an 87% risk of developing breast cancer at some point in her life. The abnormal gene also increases her risk of getting ovarian cancer, a typically aggressive disease, by 50%. To counteract those odds, Jolie wrote that she decided to have both her breasts removed. In 2010, Australian scientists found that women with the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who chose to have preventive mastectomies did not develop breast cancer over the three-year follow-up. Since the genetic abnormalities increase the risk of ovarian cancer, women who had their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed also dramatically lowered their risk of developing ovarian or breast cancers. The ability of medicine to predict one day, with relative certainty, the likelihood to develop certain conditions is an intriguing way, and leaves the open the possibility of ‘personalised medicine’ on the basis of your own individual information. If you think the NHS is already overstretched, with A&E closures contributing to the ‘crisis’ in emergency health provision, then footing a bill for personalised medicine might be the ‘straw that breaks the camel’s back’. The idea that one day you can predict the likelihood of a person developing multiple sclerosis or Alzheimer’s Disease still intrigues neurologists.

This furthermore presents formidable challenges for the law. In recent years, governments have been embracing policies that ‘nudge’ citizens into making decisions that are better for their own health and welfare, including our own Government which has decided to ‘mutualise’ its own ‘Nudge Unit’. The European Commission has embraced this ‘libertarian paternalism’ in its review of the Tobacco Products Directive. Various people has recently explained that by introducing measures such as plain packaging and display bans, the European Union may be able to ‘nudge’ people into smoking less, whilst preserving their right to choose. After having relied on the assumption that governments can only change people’s behaviour through rules and regulations, policy makers seem ready to design polices that better reflect how people really behave. Inspired by “libertarian paternalism,” the nudge approach suggests that the goal of public policy should be to steer citizens towards making positive decisions as individuals and for society while preserving individual choice.

It’s likely that a ‘one glove fits all’ policy is not going to work. About a decade ago, I was surrounded in my day job by individuals with hepatic cirrhosis, requiring abdominal paracentesis to tap away fluid from their tummies. And yet being confronted with people yellow due to the build-up of bilirubin did not deter me one jot from being a card-carrying alcohol. I am not over seventy months in recovery from alcohol misuse, so this aspect of how people make decisions before being addicted intrigues me. I think that people genuinely in addiction ‘can’t say stop’, as they don’t have an off-switch; they lack insight, and are in denial, mostly, I feel from personal experience.

It’s also clear that there is a long-list of medical problems that cause someone to present to an A&E department aside from alcohol, such as a sore-throat, faint, dislocated shoulder, and so on. But alcohol is undeniably a big issue, so the question is a sobering one, pardon the pun. To what extent can we ‘nudge’ people out of alcohol-related illness? Commenting on the report out today from the College of Emergency Medicine, that highlights the pressures that Accident and Emergency (A&E) wards are under, Dr John Middleton, Vice President for Policy at the Faculty of Public Health, said:

“We quite rightly have high expectations of doctors and nurses working in emergency medicine, so it’s only fair that they get the support they need to do their jobs safely and well. One way to reduce the burden on Accident and Emergency (A&E) wards would be to tackle the reasons why people are admitted in the first place: in particular, alcohol. Given that drink related violence accounts for over one million A&E visits every year, we urgently need the government to be bold and introduce a minimum price per unit of alcohol. That would reduce the burden on overstretched hospitals and society as a whole.”

Nobody likes assessing risk, especially the consequences of an addict picking up/using again are potentially catastrophic even if in probability terms theoretically infinitesimally low. People who know about Taleb’s “Black Swan” work will know this well. And assessing harm has led others to be blasted in the public arena previously, for example Prof David Nutt who once compared the dangers of horse riding to the dangers presented by the major drugs of abuse. At a time when both the medical and legal professions at least think there should be an open debate about having ‘another look’ at the Misuse of Drugs Act (1971), hopefully a public can welcome a mature debate on this.

Even today, the news reports that introducing a law to force cyclists to wear helmets may not reduce the number of hospital admissions for cycling-related head injuries.Researchers said that while helmets reduce head injuries and should be encouraged, the decrease in hospital admissions in Canada, where the law is in place in some regions, seems to have been “minimal”. The authors examined data concerning all 66,000 cycling-related injuries in Canada between 1994 and 2008 – 30% of which were head injuries. Writing in the British Medical Journal, the authors noted a substantial fall in the rate of hospital admissions among young people, particularly in regions where helmet legislation was in place, but they said that the fall was not found to be statistically significant.

I suppose all political parties desire people with capacity to make decisions about their own lifestyle and healthcare, very much in keeping with the ‘no decision about me without me’ philosophy currently in vogue. If push came to shove, if I could predict the future of my health, would I fundamentally change my behaviour? Probably within reason, but the only thing which I am pretty certain about is having another alcoholic drink may lead to a pattern of behaviour that will ultimately kill me.

It was honour to speak to a group of suspended Doctors on the Practitioner Health Programme this morning about recovery

It was a real honour and privilege to be invited to give a talk to a group of medical Doctors who were currently suspended on the GMC Medical Register this morning (in confidence). I gave a talk for about thirty minutes, and took questions afterwards. I have enormous affection for the medical profession in fact, having obtained a First at Cambridge in 1996, and also produced a seminal paper in dementia published in a leading journal as part of my Ph.D. there. I have had nothing to do with the medical profession for several years now, apart from volunteering part-time for two medical charities in London which I no longer do.

I think patient safety is paramount, and Doctors with addiction problems often do not realise the effect the negative impact of their addiction on their performance. No regulatory authority can do ‘outreach’, otherwise it would be there forever, in the same way that Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous do not actively go out looking for people with addiction problems. I personally have doubts about the notion of a ‘high functioning addict’, as the addict is virtually oblivious to all the distress and débris caused by their addiction; the impact on others is much worse than on the individual himself, who can lack insight and can be in denial. Insight is something that is best for others to judge.

However, I have now been in recovery for 72 months, with things having come to a head when I was admitted in August 2007 having had an epileptic seizure and asystolic cardiac arrest. Having woken up on the top floor of the Royal Free Hospital in pitch darkness, I had to cope with recovery from alcoholism (I have never been addicted to any other drugs), and newly-acquired physical disability. I in fact could neither walk nor talk. Nonetheless, I am happy as I live with my mum in Primrose Hill, have never had any regular salaried employment since my coma in the summer of 2007, received scholarships to do my MBA and legal training (otherwise my life would have become totally unsustainable financially apart from my disability living allowance which I use for my mobility and living). I am also very proud to have completed my Master of Law with a commendation in January 2011. My greatest achievement of all has been sustaining my recovery, and my talk went very well this morning.

The message I wished to impart that personal health and recovery is much more important than temporary abstinence, ‘getting the certificate’ and carrying on with your career if you have a genuine problem. People in any discipline will often not seek help for addiction, as they worry about their training record. Some will even not enlist with a G.P., in case the GP reports them to a regulatory authority. I discussed how I had a brilliant doctor-patient relationship with my own G.P. and how the support from the Solicitors Regulation Authority (who allowed me unconditionally to do the Legal Practice Course after an extensive due diligence) had been vital, but I also fielded questions on the potential impact of stigma of stigma in the regulatory process as a barrier-to-recovery.

I gave an extensive list of my own ‘support network’, which included my own G.P., psychiatrist, my mum, other family and friends, the Practitioner Health Programme, and ‘After Care’ at my local hospital.

The Practitioner Health Programme, supported by the General Medical Council, describes itself as follows:

The Practitioner Health Programme is a free, confidential service for doctors and dentists living in London who have mental or physical health concerns and/or addiction problems.

Any medical or dental practitioner can use the service, where they have

• A mental health or addiction concern (at any level of severity) and/or

• A physical health concern (where that concern may impact on the practitioner’s performance.)

I was asked which of these had helped me the most, which I thought was a very good question. I said that it was not necessarily the case that a bigger network was necessarily better, but it did need individuals to be open and truthful with you if things began to go wrong. It gave me a chance to outline the fundamental conundrum of recovery; it’s impossible to go into recovery on your own (for many this will mean going to A.A. or other meetings, and discussing recovery with close friends), but likewise the only person who can help you is yourself (no number of expensive ‘rehabs’ will on their own provide you with the ‘cure’.) This is of course a lifelong battle for me, and whilst I am very happy now as things have moved on for me, I hope I may at last help others who need help in a non-professional capacity.

Best wishes, Shibley

My talk [ edited ]

Coping being a professional in recovery: some personal thoughts for my talk

I’ve accepted an invitation to give a talk on May 10th 2013 on coping with being a professional in recovery.

I am posting my notes here in the hope that they may be useful to people one day.

Coping being a professional in recovery

Complicated area – personal thoughts – “no right answer!”

A. Being in recovery is a way of enjoying what life has to offer, not being dominated by your ‘drug of choice’.

There’s a temptation to think of some addictions as ‘morally superior’ to others: e.g. ‘alcoholism is not as bad as heroin addiction’. This is not all true – they are all equally destructive.

Common question on Twitter: “How do I know if I am an alcoholic?”

in a reply not giving any medical advice, “Because you can never stop at one drink.” (either end up in a police cell or in Medical Admissions.

Never ‘too late’ to enter recovery – even if you think your life cannot get any more disastrous. It can get more disastrous, surprisingly.

B. The legal doctrine of proportionality

Not personal – can seem that way.

GMC have a statutory duty for patient safety – their application of the law has to obey the legal doctrine of proportionality (necessary/legitimate aim) vs the ‘needs’ of the individual. This is undoubtedly a tricky balance to decide upon.

C. The media

Feb 2012, Daily Mail: Special Investigation: Why ARE so many doctors addicted to drink or drugs?

Can be a reactionary issue like foreign doctors/immigration etc.

“Disturbing new research reveals that one in six doctors has been hooked on alcohol or drugs. How has this happened – and what are the implications? According to shocking new figures, up to one in six doctors will have been addicted to drink or drugs – or both – at some stage in their medical career, raising the horrifying prospect that these highly-paid carers may have your life in their trembling hands.”

November 2012, Independent: The doctor battling drink and depression will see you now …

“Thousands of doctors are continuing to treat patients while hiding their own problems with drink, drugs and depression because of a “culture of invincibility” among health professionals. Each year hundreds of medics are treated for addiction and mental health issues, according to official statistics. But researchers investigating the issue say that this masks a much bigger problem, with thousands of doctors concealing their symptoms.1,384 doctors who had been assessed for underlying health concerns over the past five years. Of these, 98 per cent were diagnosed with alcohol, substance misuse or mental health issues.”

D. Some immediate thoughts

- Insidious progression between problem drinker and ‘serious alcoholic’.

- Patient safety – extremely important, but also important for regulators to resist any urge to find scapegoats.

- Poor performance management of trainees ?needs supervisors to be alert to and sensitive to problems (health, pt. safety, training record, needs of hospital).

- A referral to a regulatory body should not be a ‘substitute’ for sorting out performance issues for health locally.

- Need to build a culture of trust.

- A referral to a regulatory body can be used by all staff involved for the purposes of ‘covering their backs’, but not actually dealing with the problem as it arose.

- Tendency to airbrush

- Prone to overintellectualise – attributes of an alcoholic: telling lies, conceal the truth. Mitchell and Hirschman (2006) : “Forty-one of those patients (87%) kept the drinking hidden from treatment staff.” This project examined the frequency of within treatment drinking and surreptitious drinking among patients who attended a brief substance abuse treatment program that mandated within treatment abstinence.

E. Playing the blame game

Regulators hate it if the patient blames everyone except him or herself.

However this should not ignore widespread issues of culture which need a mature sensitive debate (can healthcare staff ‘whistleblow’ constructively on other staff in the pursuit of patient safety?)

Learning from mistakes – rehabilitation v retributive justice. “Zero fault” approach

Problems with the ‘blame game’ – denial and lack of insight by the patient himself or herself Duffy (1995)

If you have a drinking problem, you may deny it by:

- Drastically underestimating how much you drink

- Downplaying the negative consequences of your drinking

- Complaining that family and friends are exaggerating the problem

- Blaming your drinking or drinking-related problems on others and lack of insight

F. The “steps”

Step 1: WE ADMITTED WE WERE POWERLESS OVER ALCOHOL – THAT OUR LIVES HAD BECOME UNMANAGEABLE. (Step One consists of two distinct parts: (1) the admission that we have a mental obsession to drink alcohol and this allergy of the body will lead us to the brink of death or insanity, and (2) the admission that our lives have been, are now, and will remain unmanageable by us alone.)

The “steps” in full:

- We admitted we were powerless over alcohol – that our lives had become unmanageable.

- Came to believe that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

- Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.

- Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.

- Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.

- Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character.

- Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.

- Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all.

- Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.

- Continued to take personal inventory, and when we were wrong, promptly admitted it.

- Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out.

- Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics, and to practice these principles in all our affairs.

G. How do you know if you have a drinking problem?

You may have a drinking problem if:

- Feel guilty or ashamed about your drinking.

- Lie to others or hide your drinking habits.

- Have friends or family members who are worried about your drinking.

- Need to drink in order to relax or feel better.

- “Black out” or forget what you did while you were drinking.

- Regularly drink more than you intended to.

- Start drinking before you go out socially

- Drink on your own in bars

- Go to off-licences or supermarkets to buy cheap alcohol

- Don’t care if you’re ‘performance’ is substandard at work.

Common ‘issues’:

- Repeatedly neglecting your responsibilities at home or work, because of your drinking. ?house untidy, deferring ‘activities of daily living’ e.g. culture, shopping

- Using alcohol in situations where it’s physically dangerous, such as drinking and driving, or drinking the day before a heavy workload

- Experiencing repeated legal problems on account of your drinking. ?how many Doctors facing suspension voluntarily offer their PNC or CRB ?should Doctors be asked to submit this information as part of the revalidation process in future (note comments about outreach)?

- Continuing to drink even though your alcohol use is causing problems in your relationships.

- Drinking as a way to relax or de-stress/coping with ‘success’. Many drinking problems start when people use alcohol to self-soothe and relieve stress. Getting drunk after every stressful day, for example, or reaching for a bottle every time you have an argument with your boss.

H. Why are “professionals” particularly vulnerable?

Gossop et al. (2000): “There are several reasons why doctors and other health care professionals may be at risk of drug and alcohol misuse. The long years of medical training are characterized by intense competition, excessive workload and fear of failure, and few occupations face the intense stresses experienced in the daily practice of medicine”.

Personal experience from recovery meetings: city lawyers, traders, hospital managers, journalists

I. “Presenteeism” – seeking help is seen as getting a criminal record?

Dr Max Henderson, from King’s College London’s Institute of Psychiatry, believes that these numbers represent the tip of the iceberg because “doctors are often deterred from admitting that they are sick and need time off by feelings of shame.

A recent study led by Dr Henderson showed that medics who do fall ill fear being perceived as “weak” or “a failure” by colleagues. “There is a feeling among doctors, that illness shouldn’t happen to them – that they should somehow be invincible,” said Dr Henderson.

“Doctors are particularly vulnerable to ‘presenteeism’ and we know they are reluctant to use mainstream healthcare services and will sit on their symptoms and not share them with anyone. So they may treat themselves or they try to get their friends to treat them through what are known as ‘corridor consultations’.”

J. The difference between recovery and abstinence / white knuckling

For most serious alcoholics, it is easier to abstain altogether, rather than to engage in controlled, responsible, non-intoxicated drinking.

The idea of controlled drinking (or controlled drug use) is the one hope almost every addict brings to his or her initial encounter with treatment. As one AA veteran put it: “If it were possible for a majority of alcoholics to revert to controlled drinking, every alcoholic in AA would have found out about it a long time ago.”

The ‘dry drunk’ phenomenon: This describes a phenomenon in which a person stops drinking and using, but does not make any other significant changes in his life. They are known as “dry drunks” because even though they are sober, their behavior mirrors that of someone who is drinking.

Specialist advice for disulfiram and acamprosate, e.g.

K. Features of alcohol dependence

Alcoholism is the most severe form of problem drinking. Alcoholism involves all the symptoms of alcohol abuse, but it also involves another element: physical dependence on alcohol. If you rely on alcohol to function or feel physically compelled to drink, you’re an alcoholic.

Tolerance: The 1st major warning sign of alcoholism

Do you have to drink a lot more than you used to in order to get buzzed or to feel relaxed? Can you drink more than other people without getting drunk? These are signs of tolerance, which can be an early warning sign of alcoholism. Tolerance means that, over time, you need more and more alcohol to feel the same effects.

Withdrawal: The 2nd major warning sign of alcoholism

Do you need a drink to steady the shakes in the morning? Drinking to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms is a sign of alcoholism and a huge red flag. When you drink heavily, your body gets used to the alcohol and experiences withdrawal symptoms if it’s taken away.

These may include:

- Anxiety or jumpiness

- Shakiness or trembling

- Sweating

- Nausea and vomiting

- Insomnia

- Depression

- Irritability

- Fatigue

- Alcohol withdrawal fits

- Loss of appetite

- Headache

Waking up in the morning – needing to go to a pub

L. Two myths of ‘alcoholism’

a. I’m not an alcoholic because I have a job and I’m doing okay.

You don’t have to be homeless and drinking out of a brown paper bag to be an alcoholic. Many alcoholics are able to hold down jobs, get through school, and provide for their families. Some are even able to excel.

The myth about “the high functioning addict”.

b. Drinking is not a “real” addiction like drug abuse.

Alcohol is a drug, and alcoholism is every bit as damaging as drug addiction. Alcohol addiction causes changes in the body and brain, and long-term alcohol abuse can have devastating effects on your health, your career, and your relationships. Alcoholics go through physical withdrawal when they stop drinking, just like drug users do when they quit.

M. Recovery is an ongoing process

Recovery is a bumpy road, requiring time and patience.

The GMC fitness to practise procedures are reported by many, anecdotally, to be time consuming, but they also involve a huge commitment from GMC staff, panel members and specialist advisors. The problem comes to ensure that the mental health of people under investigation does not deteriorate in the lengthy process.

Stress can make addictive symptoms worse, but if right regulatory process can help encourage people in recovery.

Regulators should avoid giving any impression of criminalising people for illness, or humiliating people unnecessarily in the course of their proceedings. There should be a real effort to preserve the dignity of ill people, as Doctors can be patients too. This requires a commitment of being proportionate in a definite drive for destigmatisation, whilst preserving the duty of public safety in the utmost. This requires a shift in mindset of a view where some people cannot be treated for mental illness such as addiction.

N. Support networks

Tendency to ‘get the certificate’ than to understand the process of recovery.

1. Practitioners Health Programme

Dr Clare Gerada, Chair of the RCGP and PHP’s medical director, said: “We are seeing more sick doctors, more GPs in particular, more shame, more presenteeism, as doctors are worried about their futures. ”

2. British Doctors and Dentists Group – all ages, diverse backgrounds

The British Doctors and Dentists Group was formed originally for doctors who were attempting to recover from alcohol dependency and other substance abuse over 30 years ago. The late Dr Max Glatt encouraged some of the early members to form a group which met for mutual support on a monthly basis.

3. After Care

4. Psychiatrist/GP (nb GMC Good Medical Practice)

5. Friends/family/peers

6. ?Regulatory bodies

7. AA or similar entities.

END