“Society has moved on, and people expect more from their services.”

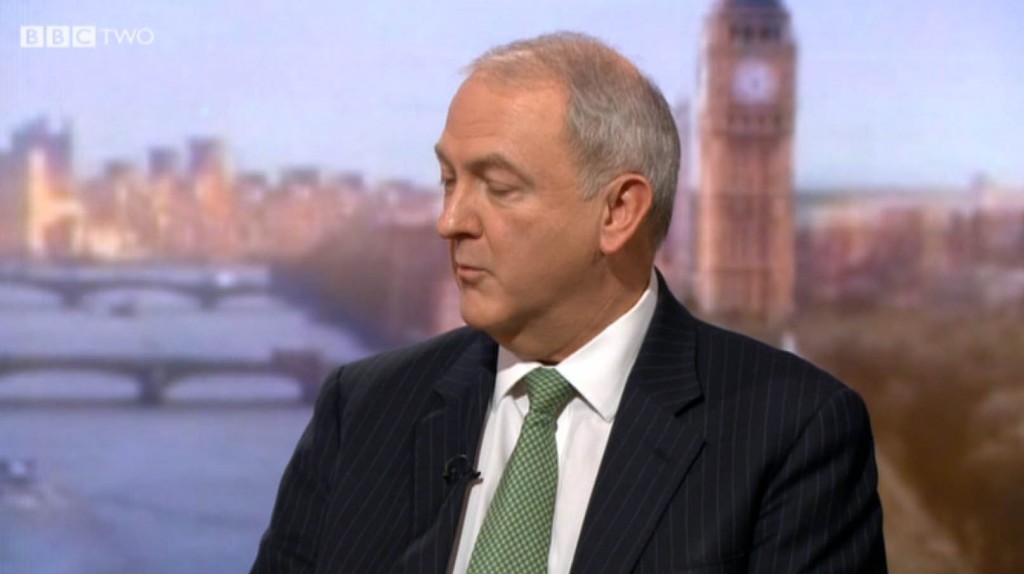

This was the fairly harmless way in which Sir Bruce Keogh, the Medical Director, commenced his interview with Jeremy Vine on “The Andrew Marr Show” this morning. And that of course is motherhood and apple pie at its best.

Keogh may not actually have a problem at all on his hands, as the vast majority of NHS Trusts in England have been doing some form of 24/7 for years. In fact, it’s well known that many NHS consultants who have received ‘clinical excellence awards’ have been working 24/7 for ages, without even batting an eyelid.

Keogh then dropped the bombshell that, historically, we’ve been very good at providing services five days a week, but there was an evidenced problem with mortality in hospitals at the weekends. Keogh also proposed that junior doctors are feeling particularly stressed at the weekends, because of the complexity of diagnosis and treatment, and Keogh felt that, “We should worry about that because we could be training our next generation of doctors better.”

A major drive has been to have more Consultants ‘on the ground’ 24/7, though most people concede that to run a full offering, there will need to be to some extent 24/7 input from physiotherapists, OTs, speech therapists, dieticians, allied health professionals, and possibly even secretaries and NHS managers.

Nonetheless, Keogh was able to formulate a perfectly cogent case for NHS Consultants being there 24/7: “If you have more Consultants present, you don’t have as many inappropriate admissions. Secondly, they… get more appropriate treatment. This will cost 1.5-2% of the annual costs of running a hospital.”

Keogh introduced the fact that this new approach would require more specialists, and this would cost money. “We need to find the money from somewhere. One of the most expensive costs is the cost of workforce. We’re about to produce 1800 more specialists.”

This is what Andy Burnham MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Health, has asked about time and time again. Even Burnham has probably got fed up of banging his head against this particular brick wall.

However, the most revealing part of the interview was when this morning’s presenter of the Marr Show, Jeremy Vine, asked about the actual practical issue: as to whether the NHS could simply change contracts.

Keogh responded, “Most of my consultant colleagues are in at the weekend anyway.”… “All people in the NHS, from the managerial community, think it’s the right thing to do.”

This drew polite short shrift from Vine, “The fact that there are some nice consultants is neither here nor there.”

Clearly the entire NHS cannot be run on the goodwill of Keogh’s pals. Keogh instead offered that,

“This isn’t about money, it’s about flexible working practices, and better recruitment. We believe the arguments for this are compelling.”

And the indeed the problem is not in introducing new contracts for new Consultants in the NHS. You can simply introduce new terms and conditions for them. It is what to do with existing Consultants with existing employment contracts.

The general position in English employment is that a party cannot unilaterally vary the terms of a contract. The position reflects the principle that a unilateral material change of terms may equate to a fundamental ‘repudiatory’ breach of contract. A repudiatory breach is one that is so fundamental to the contract that the aggrieved party may terminate it and sue for damages. Of course, it could be that there is no change in contract as ‘consultants are doing this anyway’. But it is not unheard of for all NHS staff, of all ranks, to do work effectively for free (for example checking up on liver function tests in a cirrhotic patient with a queried life-threatening subacute peritonitis.) However, the position is not so straight forward where a party is allowed to amend a contract unilaterally by virtue of a term in that contract.

If an employer tries to impose a variation of contract, they will potentially be in breach of contract.

To decide whether they are, two initial questions have to be asked:

- Is the term being varied a term of the contract? And, if so, does the employer have the right to unilaterally vary it?

- Working hours will invariably an explicit term of that employment contract between a NHS consultant and a Trust.

However, terms enabling unilateral variation are allowed in contracts and are not that hard to find. Two widely used examples in the commercial world are those granting sellers the power to change the price of their goods and those granting lenders the right to vary the rate of interest charged.

There are a number of ways that an employer can change/vary your employment contract legally. By obtaining your consent to vary/change the contract of employment. This can be done either orally or in writing, although it is better in writing. Any employer can imposing changes/variations to your employment contract with your implied consent. An example of this would be if your employer brought in new terms and conditions, and you did not raise any objection to them after they had been brought in and you continued to work in accordance with the new terms and conditions. Here it’s going to be critical to see what the precise reaction of the BMA is, often referred to in the BBC and the professional press as “the Doctors’ Union”. By relying on an existing clause in an employment contract that gives the employer the contractual right to vary/change the contract. These clauses are more commonly referred to as “variation clauses” or “flexibility clauses”. For a variation clause to be enforceable, it must be clear, specific and unambiguous. These clauses are terms in a contract that give employers the right to change some other condition of employment, eg relocation to a hospital as part of a regional network of Trusts.

If this Government, or indeed any Government, wished to ‘steamroller’ this policy of 24/7 for NHS consultants, there are two possible basic approaches, both of which entail legal risks and potential damage to general employer/employee relations. The employer make a unilateral change to the existing contract by simply announcing the change and implementing it forthwith or with notice. Or the employer could simply terminate the existing employment contract with proper notice (whilst complying with the statutory dismissal procedures), and offer re-engagement on a new contract which reflects the amended terms If the employer adopts the first approach, the employee may accept the change despite an initial protest. However, employees may continue to protest, insist on the terms of the original contract, and either bring a claim for breach of contract or resign and claim “constructive dismissal”.

Alternatively, they could work under the new terms, but “under protest” which means they reserve their right to claim breach of contract or, in limited cases, unfair dismissal. The employer would be unlikely to have a defence to these claims and the tribunal may not only award compensation for the loss previous employees have suffered as a result of the change or dismissal but also make an award that these employees are in fact reinstated to their job on their original terms. If approach two is adopted, the employee is being dismissed and can therefore still claim unfair dismissal. However, if there is a reasonable consultation process an employer would be more likely to be able to defend a claim on this basis than under approach one and more likely to minimise any compensatory payments. Importantly, however, the change will not be revoked and the employee will have to bring any action within three months of the dismissal.

All of these legal issues of course assume that NHS Consultants, if they were in such a professional situation, would be properly legally advised. The cost in legal fees, and legal claims in general, is not an unknown notion for the NHS currently given the estimated £3bn implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) which outsourced the NHS, set up a stronger insolvency regime for ‘failing hospitals’, and gave greater powers to the economic regulator of the NHS (“Monitor”).

This has been criticised previously in the GP magazine:

“From then on, each management level may resort to bullying those below in order to force these unworkable policies through, complete with personal threats of what will happen if their orders are not obeyed or targets not hit. This is when managers can throw their weight around by insisting that ‘this is government policy’ and therefore ‘you will carry this out’ — if only to make their own jobs secure. We have here the NHS version of constructive dismissal: the setting of impossible targets, which are then cascaded throughout the entire organisation. And because these goals are ultimately unattainable, compliance has to be attempted through intimidation rather than the use of logical argument. I’m sure that this scenario explains why bullying in the NHS has now become endemic.The solution is simple: creating an impossible target should be treated in law both as bullying and constructive dismissal. Those who do it should be sacked from the NHS and told never to return.”

As for the basic issue, it is perhaps laudable that Keogh and the NHS, under this administration or any other, should wish hospitals to be run 24/7 like any other organisation. The legal issues will have to be overcome, but the major issue is still resources. The comparable situation in a supermarket would be like having the doors open but with fewer cashier assistants, no people supervising cashiers, no people doing “store fills” (they’re the people who ensure the store shelves are well stocked and that the shop is clean and tidy for when you, as customers are in the store), checkout supervisors, bakery managers (if the bakery is an essential part of your offering), and so on.

Disclaimer: This blogpost should not be construed in any way as a professional legal opinion. It is simply an academic comment.

Pingback: The legal problem for Keogh is potentially an u...()