Home » Access to treatment

We do not wish to use their NHS

If we get another Conservative government, the Tories will be changing their mantra from the coded “The NHS is not sustainable” to a rather more blatant “WE do not want to use their NHS”.

Let the proles eat cake (from the food bank) – or play bingo with cheap pints?

ht Alex Andreou

The vast majority of interactions between individual citizens and the NHS are free at the point of use, including GP visits, Accident and Emergency admissions, and practically all the programmes of treatment which can follow on from them.

And there’s no doubt the rich are getting richer. Despite the tough economic conditions, the super-rich are getting richer, with the number of millionaires in the UK almost doubling in just two years uptil 2013.

Figures from HM Revenue & Customs showed there were 18,000 people earning £1m or more in the last tax year preceding the middle of 2013. Just two years previously, there had been only 10,000 in this income bracket. This is a significant increase on the 4,000 income millionaires recorded by the Revenue in the year 2000. The HMRC figures also show that more people are earning six-figure salaries. An additional 5,000 people now earn between £500,000 and £1m compared with two years ago; while a further 31,000 earned between £200,000 and £500,000 and 7,000 earned between £150,000 and £200,000. These figures cumulatively suggest that there is a growing disparity between the top earners – many of whom work in the financial sector – and the rest of society.

Mandelson may be ‘intensely relaxed’ about it all – but is he intensely relaxed about who pays for the NHS?

Whenever you hear news about wanting to bring in charges for the NHS, attention is never paid to the very rich who could afford to pay. Politicians of a certain ilk, enabled by a supine media, perpetuate the meme ‘the NHS is not sustainable’ demonstrating unsurpassable stupidity. It is not that the NHS is unsustainable – it’s just that some people feel they ought not to be contribuing to it out of general taxation. And the rest of the sheep follow.

The Cameron-led government may have wished to convey an ethos of ‘libertarian paternalism’, where we are nudged into decisions in the market. But it is now generally conceded that there are many decisions which are profoundly unsuitable for ‘Nudge’. Like a stubborn stain which refuses to go on a repeat wash and spin cycle, the Conservatives still want to be patricians. The problem is they’re failing at that.

Books have been written on the famous Harold Macmillan phrase, “You’ve never had it so good.” A number of reasons converge into Macmillan’s economic failure, but the phrase itself reinforces a sense of ‘them against us’. In spite of the talk about a social revolution in capitalism has not changed. It is still a system of minority wealth and mass poverty and insecurity. The only real dispute may be quite how large the “squeezed middle” is. Profits, stock exchange prices and the emergence of new crops of millionaires may truly mark the phase of “you never had it so good”. The Conservatives and high income Liberals don’t mind rubbishing the NHS as they hope not to use it. Whenever Grant Shapps talks about ‘hardworking people’, curiously he always talks about “them”.

The real charge sheet against David Cameron isn’t Eton or Bullingdon, arguably, but Carlton TV: how supposedly a good education is squandered for ‘ready money’. Where someone of his background might once have spent his early manhood serving with the Coldstream Guards, perhaps, he earnt his money doing PR for a television company. The legacy of the Conservative Party under the Thatcher revolution has been ‘easy money’ rather than wishing to build up an infrastructure we can all be proud of: what Miliband latterly called “the fast buck society”.

Douglas Carswell MP in the Telegraph had something quite interesting to say about it in the Telegraph in July 2013:

“Decades of patrician Toryism run out of SW1 have failed. What we need instead is insurgent Conservatism; anti big corporate interests and politics-as-usual in Westminster. Fiercely in favour of ordinary folk trying to make the most out of life.”

The Conservatives would hate to admit it but the cost-of-living crisis does resonate with voters. Also years of rubbishing the NHS has left a general public resenting the Conservatives, enabled by the Liberal Democrats, clinging onto government. In a patrician way, they legislated for a £2.4 bn implementation of the Health and Social Act (2012) which leading experts told them was fundamentally faulty because of the effect that competition would have.

It’s this arrogance and aloofness which is likely why this government will ultimately fall apart. The NHS reforms have not improved patient safety, but basically outsourced the NHS at turbo speed. Public resources have been allocated to the private sector. If it seems as if certain people don’t want to become ill in the NHS, that’s because they don’t – they want to tell you the NHS is “unsustainable” instead.

The legal problem for Keogh is potentially an unilateral variation of contract and this needs a solution

“Society has moved on, and people expect more from their services.”

This was the fairly harmless way in which Sir Bruce Keogh, the Medical Director, commenced his interview with Jeremy Vine on “The Andrew Marr Show” this morning. And that of course is motherhood and apple pie at its best.

Keogh may not actually have a problem at all on his hands, as the vast majority of NHS Trusts in England have been doing some form of 24/7 for years. In fact, it’s well known that many NHS consultants who have received ‘clinical excellence awards’ have been working 24/7 for ages, without even batting an eyelid.

Keogh then dropped the bombshell that, historically, we’ve been very good at providing services five days a week, but there was an evidenced problem with mortality in hospitals at the weekends. Keogh also proposed that junior doctors are feeling particularly stressed at the weekends, because of the complexity of diagnosis and treatment, and Keogh felt that, “We should worry about that because we could be training our next generation of doctors better.”

A major drive has been to have more Consultants ‘on the ground’ 24/7, though most people concede that to run a full offering, there will need to be to some extent 24/7 input from physiotherapists, OTs, speech therapists, dieticians, allied health professionals, and possibly even secretaries and NHS managers.

Nonetheless, Keogh was able to formulate a perfectly cogent case for NHS Consultants being there 24/7: “If you have more Consultants present, you don’t have as many inappropriate admissions. Secondly, they… get more appropriate treatment. This will cost 1.5-2% of the annual costs of running a hospital.”

Keogh introduced the fact that this new approach would require more specialists, and this would cost money. “We need to find the money from somewhere. One of the most expensive costs is the cost of workforce. We’re about to produce 1800 more specialists.”

This is what Andy Burnham MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Health, has asked about time and time again. Even Burnham has probably got fed up of banging his head against this particular brick wall.

However, the most revealing part of the interview was when this morning’s presenter of the Marr Show, Jeremy Vine, asked about the actual practical issue: as to whether the NHS could simply change contracts.

Keogh responded, “Most of my consultant colleagues are in at the weekend anyway.”… “All people in the NHS, from the managerial community, think it’s the right thing to do.”

This drew polite short shrift from Vine, “The fact that there are some nice consultants is neither here nor there.”

Clearly the entire NHS cannot be run on the goodwill of Keogh’s pals. Keogh instead offered that,

“This isn’t about money, it’s about flexible working practices, and better recruitment. We believe the arguments for this are compelling.”

And the indeed the problem is not in introducing new contracts for new Consultants in the NHS. You can simply introduce new terms and conditions for them. It is what to do with existing Consultants with existing employment contracts.

The general position in English employment is that a party cannot unilaterally vary the terms of a contract. The position reflects the principle that a unilateral material change of terms may equate to a fundamental ‘repudiatory’ breach of contract. A repudiatory breach is one that is so fundamental to the contract that the aggrieved party may terminate it and sue for damages. Of course, it could be that there is no change in contract as ‘consultants are doing this anyway’. But it is not unheard of for all NHS staff, of all ranks, to do work effectively for free (for example checking up on liver function tests in a cirrhotic patient with a queried life-threatening subacute peritonitis.) However, the position is not so straight forward where a party is allowed to amend a contract unilaterally by virtue of a term in that contract.

If an employer tries to impose a variation of contract, they will potentially be in breach of contract.

To decide whether they are, two initial questions have to be asked:

- Is the term being varied a term of the contract? And, if so, does the employer have the right to unilaterally vary it?

- Working hours will invariably an explicit term of that employment contract between a NHS consultant and a Trust.

However, terms enabling unilateral variation are allowed in contracts and are not that hard to find. Two widely used examples in the commercial world are those granting sellers the power to change the price of their goods and those granting lenders the right to vary the rate of interest charged.

There are a number of ways that an employer can change/vary your employment contract legally. By obtaining your consent to vary/change the contract of employment. This can be done either orally or in writing, although it is better in writing. Any employer can imposing changes/variations to your employment contract with your implied consent. An example of this would be if your employer brought in new terms and conditions, and you did not raise any objection to them after they had been brought in and you continued to work in accordance with the new terms and conditions. Here it’s going to be critical to see what the precise reaction of the BMA is, often referred to in the BBC and the professional press as “the Doctors’ Union”. By relying on an existing clause in an employment contract that gives the employer the contractual right to vary/change the contract. These clauses are more commonly referred to as “variation clauses” or “flexibility clauses”. For a variation clause to be enforceable, it must be clear, specific and unambiguous. These clauses are terms in a contract that give employers the right to change some other condition of employment, eg relocation to a hospital as part of a regional network of Trusts.

If this Government, or indeed any Government, wished to ‘steamroller’ this policy of 24/7 for NHS consultants, there are two possible basic approaches, both of which entail legal risks and potential damage to general employer/employee relations. The employer make a unilateral change to the existing contract by simply announcing the change and implementing it forthwith or with notice. Or the employer could simply terminate the existing employment contract with proper notice (whilst complying with the statutory dismissal procedures), and offer re-engagement on a new contract which reflects the amended terms If the employer adopts the first approach, the employee may accept the change despite an initial protest. However, employees may continue to protest, insist on the terms of the original contract, and either bring a claim for breach of contract or resign and claim “constructive dismissal”.

Alternatively, they could work under the new terms, but “under protest” which means they reserve their right to claim breach of contract or, in limited cases, unfair dismissal. The employer would be unlikely to have a defence to these claims and the tribunal may not only award compensation for the loss previous employees have suffered as a result of the change or dismissal but also make an award that these employees are in fact reinstated to their job on their original terms. If approach two is adopted, the employee is being dismissed and can therefore still claim unfair dismissal. However, if there is a reasonable consultation process an employer would be more likely to be able to defend a claim on this basis than under approach one and more likely to minimise any compensatory payments. Importantly, however, the change will not be revoked and the employee will have to bring any action within three months of the dismissal.

All of these legal issues of course assume that NHS Consultants, if they were in such a professional situation, would be properly legally advised. The cost in legal fees, and legal claims in general, is not an unknown notion for the NHS currently given the estimated £3bn implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) which outsourced the NHS, set up a stronger insolvency regime for ‘failing hospitals’, and gave greater powers to the economic regulator of the NHS (“Monitor”).

This has been criticised previously in the GP magazine:

“From then on, each management level may resort to bullying those below in order to force these unworkable policies through, complete with personal threats of what will happen if their orders are not obeyed or targets not hit. This is when managers can throw their weight around by insisting that ‘this is government policy’ and therefore ‘you will carry this out’ — if only to make their own jobs secure. We have here the NHS version of constructive dismissal: the setting of impossible targets, which are then cascaded throughout the entire organisation. And because these goals are ultimately unattainable, compliance has to be attempted through intimidation rather than the use of logical argument. I’m sure that this scenario explains why bullying in the NHS has now become endemic.The solution is simple: creating an impossible target should be treated in law both as bullying and constructive dismissal. Those who do it should be sacked from the NHS and told never to return.”

As for the basic issue, it is perhaps laudable that Keogh and the NHS, under this administration or any other, should wish hospitals to be run 24/7 like any other organisation. The legal issues will have to be overcome, but the major issue is still resources. The comparable situation in a supermarket would be like having the doors open but with fewer cashier assistants, no people supervising cashiers, no people doing “store fills” (they’re the people who ensure the store shelves are well stocked and that the shop is clean and tidy for when you, as customers are in the store), checkout supervisors, bakery managers (if the bakery is an essential part of your offering), and so on.

Disclaimer: This blogpost should not be construed in any way as a professional legal opinion. It is simply an academic comment.

Is technology a friend of the NHS?

Imagine if you could 3-D print a pink diamond.

Or a £50,000 note.

The world would truly be your oyster.

3-D printing has inevitably received its share of hype. But in this case, the excitement could conceivably be justified. 3-D printing is one of 12 technologies that the McKinsey Global Institute recently identified as having high potential for economically disruptive impact between now and 2025.

Technology can be sexy.

You have to be quite astute, sometimes, to dodge what may seem like manifestations of the latest fat.

Can robots be companions for the elderly?

However, some of the aspects of the NHS are much more mundane; even depressing.

Professor Michael Porter, the world expert in competition, often used to cite in lectures at Harvard how technology itself often doesn’t necessarily mean ‘a competitive advantage’.

This year, it was announced that the costs of the multibillion-pound national health IT programme abandoned by the government are set to continue rising significantly.

The Commons public accounts committee issued the warning as it branded the scheme one of the “worst and most expensive contracting fiascos” in the history of the public sector.

And yet – curiously at the same time – the UK now needs to become world class at developing, testing and rapidly

diffusing the best new technologies and practices.

In June this year, NHS England called on the public, NHS staff and politicians to have an open and honest debate about the future shape of the NHS in order to meet rising demand, introduce new technology and meet the expectations of its patients. This is set against a backdrop of “the funding gap”.

New technology is considered either an opportunity or a threat, depending on how expensive it is.

But a new technology doesn’t necessarily need to be expensive.

A “disruptive innovation” is an innovation that helps create a new market and value network, and eventually goes on to disrupt an existing market and value network (over a few years or decades), displacing an earlier technology.

The term is used in business and technology literature to describe innovations that improve a product or service in ways that the market does not expect, typically first by designing for a different set of consumers in a new market and later by lowering prices in the existing market.

The concern, however, is that the NHS faces tighter financial constraints, a plethora of new private providers will seek new ways of capitalising on the new NHS market. In economic terms, the Health and Social Care Act (2012) has produced the correct ‘rent extraction’ environment for companies seeking to maximise shareholder dividend.

The added concern for some healthcare analysts is that this is diverting resources away from front-line care.

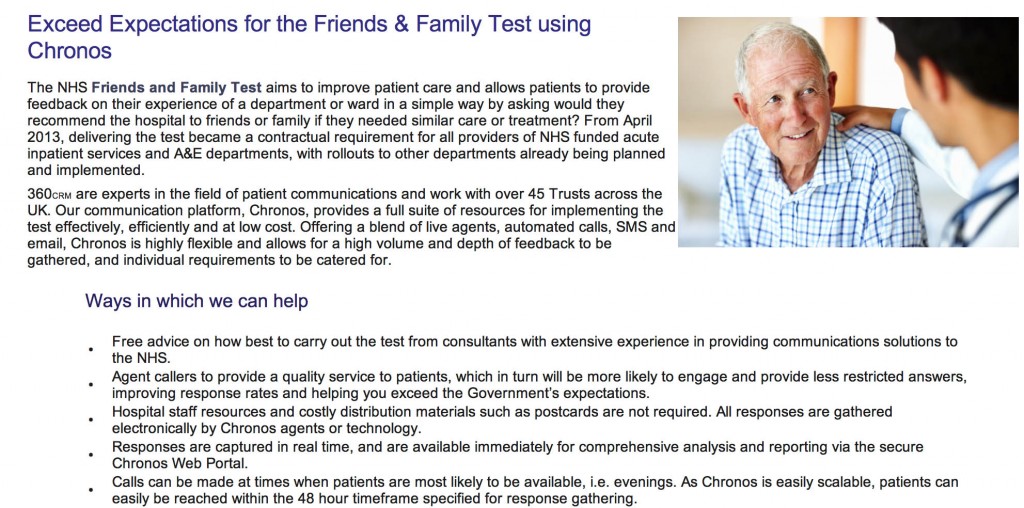

For example, here is a pitch from a provider of “The Friends and Family Test”:

Please click here for a magnified version of this image. You can read from the first paragraph why commissioning this would be so attractive to NHS Trusts, as they all gear up to be Foundation Trusts by the end of 2014.

Publishing has seen innovations which have been ‘revolutionary’. Similar to Gutenberg’s printing technology that replaced handwritten manuscripts, digital technology is replacing printed books. Paper replacing parchment; desktop publishing replaced typesetting, and so on.

Cheaper doesn’t though necessarily mean worse. An ipad to screen for dementia isn’t necessarily better than pen-and-paper.

Some years ago, a group published a paper in the BMJ.

They had sought to evaluate evaluate a brief screening test, the TYM (“test your memory”), in the detection of Alzheimer’s disease. They examined its efficacy in outpatient departments in three hospitals, including a memory clinic.

They involved a large number of people. They included 540 control participants aged 18-95 and 139 patients attending a memory clinic with dementia/amnestic mild cognitive impairment.

They found that the TYM can be completed quickly and accurately by normal controls. They concluded, by comparing the test’s performance to other instruments, that it was a powerful and valid screening test for the detection of Alzheimer’s disease.

Another system of the body provides an equally interesting example.

PCP is an infection of the lungs caused by Pneumocystis jiroveci, which is a common micro-organism in people. It causes disease only in people with weakened immune systems, such as those who have had transplants, chemotherapy, or advanced HIV infection. As the infection progresses, the air spaces in the lungs fill with fluid, making it harder to breathe.

You can apply a ‘pulse oximeter’ to the index finger of an individual to measure non-invasively an oxygen saturation. A ‘tight’ chest and shortness of breath can occur when climbing stairs. This can be evidenced by the pulse oximeter’s change in readings from high to low. This is not a particularly expensive test, say compared to a high-resolution CT scan.

These aren’t of course definitive tests, but simply demonstrations of cheapish equipment can be helpful in medicine without exploding the technology budget.

As a final example, one can think of home pregnancy tests which detect the hormone human chorionic gonadotropin, or hCG. In general, the human body produces detectable levels of this so-called pregnancy hormone only when a blastocyst has implanted into the wall of the uterus. While false positives are rare, there are are several interesting causes of a positive pregnancy test. Very rarely, a positive pregnancy test may be the first indication of a tumour in the ovaries, uterus or endometrium. The amount of hCG secreted by these tumours will vary dramatically depending on the type of tumour. Levels can be sky-high on occasion. Even sophisticated algorithms on computers can get it wrong.

Part of the well-founded anxiety in non-clinicians operating the NHS 111 algorithm is that a call handler might miss a life-threatening meningitis if the correct constellation of symptoms around a headache is missed. The end-point of such calls apparently from the algorithm is ‘go to A&E’ or an ambulance, so hopefully such cases are picked up.

Stephen on the ‘Lex Futurus’ blog (@lexfuturus is PwC’s lead in innovatively transforming legal services) hit the nail-on-the-head for the legal industry, and lessons should be learnt by the medics too.

It’s all about using technology intelligently, stupid.

We now live in a world of email, smart phones, automated document production and Nespresso machines. We have better technology than Roger Moore’s 007 (although there are meetings I would have dearly loved access to his exploding pen) yet, we are working harder and not necessarily smarter.

For in-house lawyers, there should be a “thinking premium” (unless they can negotiate better hours with their CEO) which the technology proffers them, to allow observation, analysis, reflection and strategising – to lift in-housers up from the tyranny of case-by-case reactivity but to think on a proactive basis at an enterprise level.Instead of the “silver bullet” technology promises, in many cases IT would appear to add to the burden of legal teams, requiring them to extract reports, manipulate into excel, collate additional data manually or, in some cases, do and enter everything twice.

..

In truth, we are sold IT as a panacea – the answer to all our many woes. Well choreographed presentations are whizzed through but smart tech-types, demonstrating how their solution is the key to unlocking our efficiency... IT can be game changing – just make sure you know the game your playing and that you’ve got the tactics mapped out.

These are lessons which could be beneficially considered by those in NHS procurement too.

And it’s likely that assistive technology and telecare will impact, for the public good, in the dementia care of the future.

So like all friends, choose your type of technology carefully?

[Disclaimer: Do not rely on any information in this blogpost.]

The car crash interview of a Trustee of the King’s Fund about potential payments for the NHS

The political parties have two strands of consensus which at first blush may seem somewhat irreconcilable: a NHS which is universal, and free-at-the-point-of-need, and £15-20 ‘efficiency savings’ within the next few years.

Taxes could rise to increase the size of the public expenditure pot. thereby generating additional funds to flow into public funding for healthcare. There does not seem to be any political appetite for this approach at the moment. While technically possible (tax levels are far higher in Nordic countries than in the UK), this is unlikely to provide an answer in the short term.

The NHS is heading for a “breakdown” if people expect it carry on providing all services for free under increasing demand, the former head of Marie Curie Cancer Care has warned.

Sir Thomas Hughes-Hallett urged us to ‘take more responsibility’, encouraging us to think about what we ‘really need for free'; he gave his view of how to keep the NHS on the road, saying it should – like a a garage – charge “for extras”.

He said people “need a sat-nav” to point them what is “most convenient”, towards chemists or community support centres and “steer them away from the NHS when they don’t need it”.

He further added that people should treat their bodies like a car, with a regular MOT, and that “we need to take more responsibility for our own health”.

Hughes-Hallett, a trustee of the King’s Fund, and Executive Chair of the Institute of Global Health Innovation at Imperial College, London, predicted: “We need to make tough choices for now about what we really need for free”.

Unfortunately, Sir Thomas was a guest on Wednesday’s Daily Politics today, and his defence of his own argument was worse than pitiful as you can see here (at 1 hr 29 minutes).

Andrew Neil started the discussion by enquiring off Hughes-Hallett where he “would draw the line”, mooting gastric banding, acupuncture, and varicose veins.

For fertility treatment, he said: “there is no yes or no answer.”

Neil then replied that some difficult questions would have to be answered.

Alan Duncan MP said: “It’s free-at-the-point of need and that’s not going to change…. but for the mainstream medical needs, that’s not going to change.”

Vernon Coaker MP said: “This is the thin-end-of-the-wedge. The whole point of the NHS is that’s free-at-the-point-of-use, and if you start charging, you’re going to end up with a two tier service, and the poor will be disadvantaged.”

Hughes-Hallett claimed: “Many people are willing to pay.”

The NHS could start to draw in funds from other sources, such as co-payments and supplementary insurance. Again, these could potentially start to challenge existing views on equity, because they inevitably introduce an element of some kind of payment to access services. Exemptions and subsidies can mitigate this to some extent, but the more they are used, the more they offset the expenditure benefits of alternative sources of funding in the first place.

In a recent view, the departing CEO of NHS England said that the introduction of co-payments, imminently, was “unlikely”.

A question still remains over how to deal with services that fall outside the defined core package. If they are significant in the eyes of patients, markets will develop to cover those services, funded either through fee for service or insurance-based mechanisms.

On the one hand, the development of such a market might be regarded as undermining equity (some in society will be able to pay to access health services that are not freely available to all). Others will interpret it as a natural market response that is neither desirable nor sensible to prevent — what matters is ensuring that the core package of services that is available to all is adequate.

It cannot be denied, however, that a growing number of people feel that the marketisation of the NHS has gone far too far.

In fact, many want the market abolished altogether now.

Should Doctors and Nurses act as surrogate immigration officials?

Anyone can get very ill at any time.

Anyone can get very ill at any time.

This issue is also about recognising mutual obligations and responsibilities, and looking after all our futures.

Would you like to be a British citizen abroad in France and being refused treatment?

Nonetheless, the British media has been relentless in presenting the ‘dogwhistle’ politics of immigration, rather than having an open, honest or complete debate about the NHS privatisation enacted by this Government.

Jeremy Hunt MP says today:

Having a universal health service free at the point of use rightly makes us the envy of the world, but we must make sure the system is fair to the hardworking British taxpayers who fund it.

This current Government, it has been argued, has been extremely divisive, setting off able-bodied people against disabled citizens, employed people against unemployed, and so it goes on.

The ludicrous farce of this latest announcement, of cracking down on “health tourism”, is that similar announcements have been made before. In the meantime, Hunt has been forced to apologise for a tweet when faced with legal action, and there has been talk of an impending crisis in acute medicine.

Today’s announcement will again see Ministers facing renewed claims that GP surgeries are being turned into “border posts”.

In its three years in power the government has a poor record on announcing policies that sound good but prove to be completely unworkable

(shadow health minister Liz Kendall, previously)

The Chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners, Prof Clare Gerada, has previously warned that:

“GPs must not be a new ‘border agency’ in policing access to the NHS. While the health system must not be abused and we must bring an end to health tourism, it is important that we do not overestimate the problem and that GPs are not placed in the invidious position of being the new border agency.”

Today, the Department of Health is publishing the first comprehensive study of how widely migrants use the NHS. These independent findings show the major financial costs and disruption for staff which result from a system which will be substantially reformed in the interests of British taxpayers. Just because they are ‘independent’ findings does not necessarily mean they are very accurate, as any observer of the “output” of the OBR will tell you.

Previous estimates of the cost to the NHS have varied, but this latest attempt research reveals the cost may be significantly higher than all earlier figures.

To tackle this issue and deter abuse of the system, the #omnishambles Government is proposing the following now:-

- introducing a simpler registration process to help identify earlier those patients who should be charged.

- looking at new incentives so that hospitals report that they have treated someone from the EEA to enable the Government to recover the costs of care from their home country.

- introducing a new health surcharge in the Immigration Bill to generate income for the Government (but it is unlikely this money will go into frontline patient care, as indeed the £2.4bn “efficiency savings” have not been returned either);

- appointing Sir Keith Pearson as an independent adviser on visitor and migrant cost recovery;

- identifying a more efficient system of claiming back costs by establishing “a cost recovery unit”, headed by a Director of Cost Recovery;

Andy Burnham MP, Labour’s Shadow Health Secretary, responding to Jeremy Hunt’s announcement on overseas visitors’ and migrants’ use of the NHS, said:

We are in favour of improving the recovery of costs from people with no entitlement to NHS treatment. But it’s hard not to conclude that this announcement is more about spin than substance. The Government’s own report undermines their headline-grabbing figures, admitting they are based on old and incomplete data. Instead of grand-standing, the Government need to focus on delivering practical changes. Labour would not support changes that make doctors and nurses surrogate immigration officials.

For a video of Andy Burnham MP responding to this latest report, please go here.

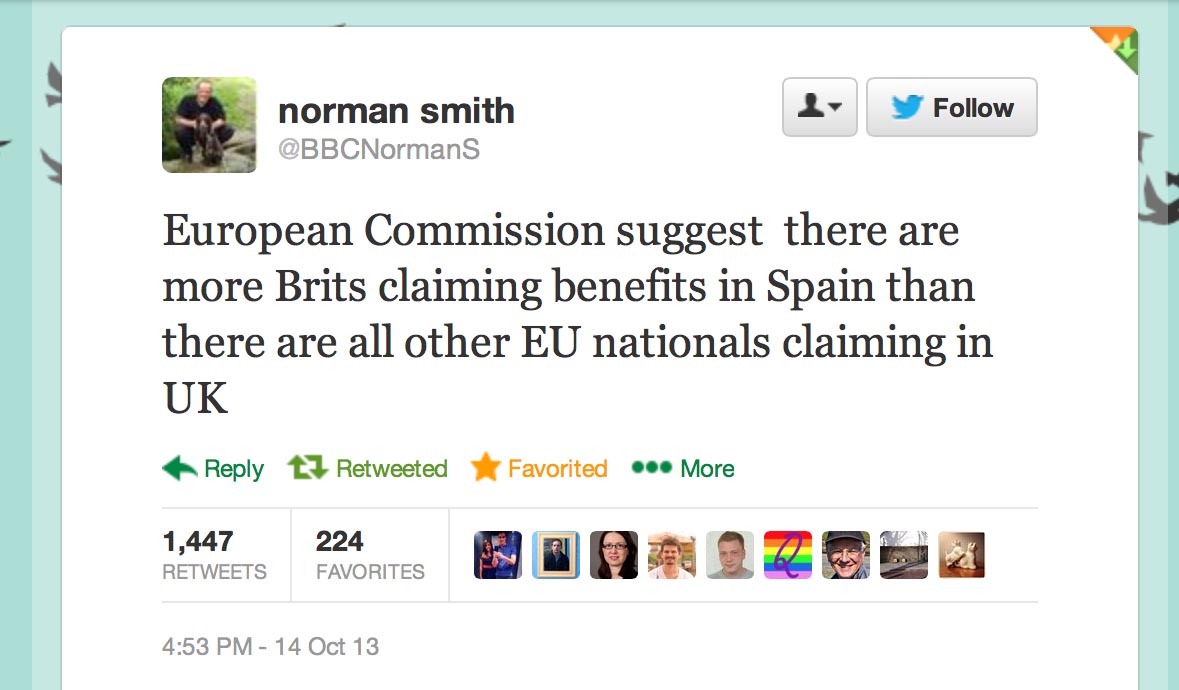

Furthermore, it appears that what Hunt won’t say about migrants is that British expatriates might make much heavier use of the NHS than any other visitors (and accordingly they should pay.)

A recent report by the European Commission concluded that so-called benefits tourism was “neither widespread nor systematic”.

As for most countries, residency not nationality primarily determines eligibility for healthcare treatment.

With the Conservative Party finding themselves ‘squeezed’ by UKIP in the run-up to the European elections, this could provide an useful smokescreen for the disaster in acute care which the Conservatives have somehow single-handedly generated.

However, the “benefits tourism” narrative of the Conservatives and UKIP was dealt a heavy blow by the emergence of this information, which the BBC’s Norman Smith tweeted earlier last week:

Last week’s announcement by Jeremy Hunt on loneliness was panned in a widespread manner by many professionals.

Last week’s announcement by Jeremy Hunt on loneliness was panned in a widespread manner by many professionals.

Maybe for the Conservatives there is ‘no such thing as Society’ after all?

Overseas visitors and migrant use of the NHS: extent and costs

Should you pay ‘extra’ to see your GP?

The outsourcing of the NHS continues to go well, as previously described, and this ‘aggravated pimping’ of the NHS was not in any political manifesto. It did really happen, though. It was not simply a bad dream. That is indeed fairly symptomatic of most incremental shifts in policy which has seen the bulk transfer of a State-run “national health service” into a private sector-dominated “fragmented illness service”. The NHS is an explosive issue, to an extent that nobody really wishes to talk about it. Labour wish to campaign on various issues as or when it suits them, such as the spike of mortality in the elderly recently reported, or on ‘whole person care’. And yet it has been perfectly happy to float ideas, such as co-payments, without much warning, though you can probably find the original seeds of such policies in a thinktank or management consultancy document a few years back. The idea of GPs charging is another one of those ideas, in that you could imagine any political party implementing it at the drop of the hat. It might be too optimistic to say ‘it will never happen’, in that many thought the 493 pages of the “Health and Social Care Act” would never happen either. Welcome to the age of policy of stealth, after yet another ‘big bang’ of NHS reforms.

The idea of GPs charging their patients fundamentally runs counterintuitive to the ‘principle of universality’, repeated here by Simon Burns MP, a Conservative, on the Department of Health website:

“An NHS that still provides a universal service, free at the point of use, and is as far removed from a US-style insurance system as any other health service on the planet.”

It’s been successfully argued that rationing to some extent has existed within the NHS or years now; for instance, for cosmetic procedures such as varicose veins stripping, alternative therapies and IVF. This appears to make financial sense at a time when the burden of ill health continues to rise, and possibly the term ‘rationing’ is a perjorative extreme of what might make reasonable policy-sense, an equitable distribution of resources for the most number of people, a fundamentally utilitarian approach. Unlike many other countries, English General Practitioners (GPs) in the UK have always acted as gatekeepers to secondary care services. A torrent of policy steps in the last two decades has seen whether GPs are somewhat ‘overzealous’ gatekeepers, for example in the initial diagnosis of a diagnosis of dementia, and whether the floodgates to secondary care should be opened through alternative routes such as “NHS 111″ (or, previously, “NHS Direct”).

A poll of 440 GPs by Pulse magazine found that 51 per cent were in favour of making patients pay a small fee for routine appointments. This latest introduction of the GPs charges policy plank came from ‘evidence’ that most family doctors think patients should be charged for appointments to deter them from turning up at surgeries ‘for no reason’, according to a poll. They apparently want the NHS to impose fees of between £5 and £25 per consultation, with some arguing that wealthier patients should pay £150 a time. Except, the evidence here is ‘flimsy’. It was done through a Survey Monkey platform, which means that, without doing a breakdown of the IP addresses, you cannot tell whether the respondents are ‘genuine’, or even from this jurisdiction. This is of course a criticism of any form of electronic market research. What is intriguing is that this poll has actually returned a verdict in favour of GPs charging, allegedly from GPs, whereas previous negative findings have not been published. This is of course exactly the statistical artefact which Ben Goldacre describes on a totally different level to how Big Pharma present the evidence to sway national policy. The Pulse survey also demonstrates a much discussed warning about electronic survey methods; that is, ‘fake respondents’ can theoretically bias the response, and this is precisely the fear in the implementation, whenever it happens, of the “Friends and Family Test”.

The numbers of patients seeking appointments is expected to double over the next 25 years. It is said that this is “driven by the ageing population with more people falling ill”, but this tragically is to submit yourself to the narrative that elderly citizens are a ‘burden’ on the rest of society, whatever social value or capital they might contribute. Of course, this basic narrative itself is resented by many. Experts say the only way the NHS will be able to afford to care for all these people is by charging for some treatments and services which are free. The majority said the charges should be between £5 and £25 per appointment but one anonymous doctor called for means testing with the wealthiest patients paying £150. We are now having this ‘frank and honest’ debate as ‘the cat is out of the bag’, or ‘the horse has bolted’. It is, of course, somewhat of a Pyrrhic victory that we can now discuss the best way of implementing privatisation of the NHS, when many of us didn’t want it in the first place, but there are a number of perceived “advantages” of introducing GP charges. Such an approach ultimately engages well with the ideological drive to reform ‘public services’, so that it is easier to “process map” a public service, and commodify it for economic purposes. GPs might argue that having a deterrent in the form of cost might be useful to stop the NHS being “abused”, in that if the front door is shut in a person’s face, he or she cannot “abuse” the rest of the service. Such restrictions on the “abuse” of GPs might lead to GPs being more respected if one believes that ‘earning power’ provides equivalence between different vocations and professions such as lawyers, plumbers or footballers. Furthermore, the money generated by such a policy move could potentially help to pay for more services, and ‘every little bit helps’, especially when at a time when the NHS is seeking ‘efficiency savings’ of the order of billions before 2020.

GPs’ charges also touches upon an emerging concept generally in policy, known as the “contributory principle”.Ed Miliband used one of his speeches speech to bring the contributory principle back into the heart of Labour thinking on welfare reform. It is less clear, however, that the contributory principle can really serve to underpin a modernisation of the welfare state for the 21st century. It only now covers around 10% of working age benefits. Critically, it is not possible simply to withdraw public services or benefits for people who are in need. Children must be housed and educated, whatever their parents have done. Article 3 of the Human Rights Act also places a floor under the welfare state, preventing people from suffering humiliating and degrading treatment through destitution. Nonetheless, reciprocity is vital to public support for the welfare state and the strength of community solidarity, hence the debate about “contribution” in wider broader terms: not just to embrace caring and community activities, but to mean reciprocity across a range of services and entitlements, whether funded by general taxation, National Insurance or hybrid state-private insurance policies. This could potentially include GPs charging, and through talking about responsibility from top-to-bottom of society Miliband has also refused to allow this debate to be focused on the poorest alone. While right-wing think-tanks and others want social justice to be reduced to what happens to an “underclass”, Labour’s leader is keeping the whole of society in view, or indeed the “One Nation” philosophy. Knowing which patients use the NHS most, or which “customers” use the NHS most to think of it in free market terms, it is argued, leads to greater clarity in resource allocation and incremental budgeting for primary healthcare services. Charging patients at the point of use, if coupled with an appropriate IT infrastructure for implementing an integrated co-ordinated service, could allow a ‘way in’ for a mechanism to allow how “money follows the patient”. It has long been held, erroneously or not. that the money in the NHS should in theory, the areas of greatest ‘activity’ (a phenomenon known as ‘activity based costing’ by management accountants).

However, it’s easily possible to mount a defence of the “status quo”. You would have thought that was the natural inclination of the “Conservative” Party? Above all, when it might seem that an overwhelming purpose of English health policy is to reduce inequality, with growing appreciation of the social determinants of disease, it will definitely be perceived as an anethema to introduce GP charges. Whatever the finding of this online survey, it can hardly be considered a policy drive of practising Doctors to introduce recklessly or knowingly ‘barriers to access’ for the financially disadvantaged or underprivileged in society. Firstly, it may not be necessary to impose shifts in English health policy, especially at a time when George Osborne is insisting that “the economy is healing” (despite the fact that Osborne claims it has been healing for the last few months, while the rate of unemployment increase has remained stable). A main concern is also that introducing GPs charging further emboldens a public perception, which the media are fond of, that GPs are in fact ‘money grabbing bastards’, and that it is not particularly fair for politicians or think tanks to breed resentment in this way. Furthermore, the policy could disproportionately discriminate against certain population demographics. For example, currently the people who make the most appointments are the elderly. Some conditions might necessarily involve a person to see his or her GP, like depression, pregnancy or disability, and it seems intuitively unfair to ‘punish’ people for needing to see their GP. Whilst there are powerful “generational attitudes” at play here, in the sense that younger people are much more likely to ‘bother’ their GP than elderly citizens for a whole host of reasons, it could be that the elderly are “the hardest hit”, as they have the greatest number of medical and social care morbidities.

The policy could also disproportionately affect individuals with a single diagnosis which embraces a number of effects across different systems of the body (e.g. ophthalmological, rheumtological, respiratory, dermatological, hepatobiliary, neurological). Examples of certain conditions have multi-system effects which have this effect, e.g. rheumatoid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis. Despite the planning of ‘integrated services’ for such conditions, a system of GP charges might simply not be able to cope. Also, patients may be put off from seeing their GP where in fact unknown to them their general medicine may demand it. For example, an individual on warfarin, an anticoagulant, following a prosthetic heart valve may not appreciate that their dosing of warfarin has changed following prescription of the antibiotic amoxicillin hospital for pneumonia. Numerous examples of the interaction of drug interactions exist, and even drug-non-drug interactions, such as grapefruit and the oral contraceptive pill, which could be completely unknown to any individual patient. The less frequently an individual sees his or her GP is bound to have an effect on the quality, both in content and style, of the doctor-patient relationship. A less frequent attendee of the NHS may find that a rarer diagnosis, e.g. of idiopathic thromboytopaenia purpura, is missed, and this could lead to substantial ‘cost implications’ distally. Charging people to see the GP might also have serious unintended consequences in policy with a shift away from a well person consulting a GP on preventive medicine to a patient having to a doctor for treatment for a medical illness or disease; this might be significant in particular medical specialties especially, for example chlamydia screening to prevent pelvic inflammatory disease, an important cause of infertility. Besides, the bother (and cost) of collecting the information for billing purposes may not be worth the hassle (and this is indeed one of the notorious criticisms of ‘activity based costing’ in management accounting described earlier.) Finally, shutting off the route of persons and patients to General Practice in any way could have damaging knock-on effects for the rest of the service. It might lead to longer queues in A&E or Early Admissions Units, which is of course a particular policy concern given a potential A&E beds crisis this winter.

This depends on whether English health policy follows or leads. Barely any policy is based on scientific evidence, especially when that evidence is so poor, with no quantitative analysis of the power or confidence of replies. However, on the balance of probabilities, it is a debate that is better ‘out than in’. The irony of research evidence purporting to reflect GPs’ views is that GPs have been comprehensively ignored in the introduction of clinical-based commissioning groups (GPs) which have no compulsion to have GPs at all as they are simply state-run insurance schemes. Any party can introduce GP charges, but in the grand scheme of things, is probably a trivial issue compared to the ‘aggravated pimping’ of the section 75 mechanism for the outsourcing and subsequent privatisation of the NHS. That is, until it happens.

Infertility treatment: when poor access-to-medicine to access-to-law come together

It is estimated that infertility affects 1 in 7 heterosexual couples in the UK. Since the original NICE guideline on fertility published in 2004 there has been a small increase in the prevalence of fertility problems, and a greater proportion of people now seeking help for such problems.

In a striking letter published on 18 June 2013 in the BMJ entitled, “NICE promises on infertility and caesarean section are unmet” from Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Hospital, Lawrence Mascarenhas (a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist), Zachary Nash (medical student), and Bassem Nathan (consultant surgeon), describe that NICE ‘promises on infertility and caesarean section are unmet’. Mr Mascharenhas and colleagues argue that “Current underfunding of the NHS means that some National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines are unachievable”. According to Matthew Limb previously, writing in the BMJ, leaders of NHS organisations in England have voiced grave warnings about how the build up of financial pressures is affecting the care of patients (Limb, 2013). Current updated NICE guidelines (CG156) recommend that women under 42 years with unexplained infertility should be offered three cycles of in vitro fertilisation funded by the NHS. Others state that all pregnant women should be able to choose an elective caesarean without obstetric or psychological indications.

The authors of this letter in the BMJ proposed that this,

“results in raised expectations that cannot be met and a flurry of referrals of disappointed women to the private sector.”

The authors specifically report that:

“Our anonymous telephone research involving all London maternity units two months ago showed that commissioners are unwilling to fund caesareans at maternal request. It also showed that women with previous caesareans are being pushed down the road of a trial of vaginal birth because of targets for reducing these operations. This causes great disappointment and anxiety for these women, who are often met with the clinician’s response “operations are more dangerous,”4 which is contrary to NICE guidance.

Furthermore, the postcode lottery for NHS funded in vitro fertilisation is well documented. We believe that these updated NICE guidelines will perpetuate the belief that these guidelines are only implementable for a

select educated few who can successfully argue their case with professionals. Others have called for legal clarity in this respect.”

The area of “judicial review” in civil litigation is the procedure by which the courts examine the decisions of public bodies to ensure that they act lawfully and fairly. On the application of a party with sufficient interest in the case, the court conducts a review of the process by which a public body has reached a decision to assess whether it was validly made. The court’s authority to do this derives from statute, but the principles of judicial review are based on case law which is continually evolving. Judicial review is very much a remedy of last resort. Although the number of judicial review claims has increased in recent years, it can be difficult to bring a successful claim and a court may refuse permission to bring a claim if an alternative remedy has not been exhausted. A claimant should therefore explore all possible alternatives before applying for judicial review.

Judicial review has a number of heads. For example, under the head of “legitimate expectation“, a public body may, by its own statements or conduct, be required to act in a certain way, where there is a legitimate expectation as to the way in which it will act. A legitimate expectation only arises in exceptional cases and there can be no expectation that the public body will act unfairly or beyond its power.

Judicial review, like arguably access to medicine, has been attacked by the current Government. The issue of infertility treatment illustrates, it can be argued, a national disgrace in poor access to both the medicine and the law. In an address to the CBI, David Cameron vowed to cut “time-wasting” caused by the “massive growth industry” in judicial reviews. He apparently wants fewer reviews, specifically for those challenging planning, and he wants to shorten the limitation period for bringing a review. This is all in aid of a new “growth cabinet” – cutting “red tape” and “bureaucratic rubbish” and “trying to speed decision making”.

Martha Gill writing in the New Statesman has argued that,

“At the moment, a judicial review is one of the only ways by which the courts can scrutinise the decisions of public bodies. Legal Aid is available for it – prisoners, for example, can bring judicial reviews against decisions of the parole board. So there are the cons – disempowering people who didn’t have much power in the first place, and increasing opportunities for public bodies to overstep the mark, unchallenged. What of the pros? Cameron argues that the judicial review industry is growing, holding up progress and costing money.”

Because of the “silo effect”, medics will have tended to notice on their watch a decline in universality and comprehensive nature of the NHS, with a focus on section 75 NHS regulations emphasising competitive tendering, but will be largely uncognisant of the battles the legal profession are facing of their own in the annihilation of high street legal aid services and cuts in judicial review. This letter in the BMJ from a leading Consultant’s firm at Guys’ and St.Thomas’ here in London demonstrates what a mess the confluence of these two policies, pretty horrific separately, can lead to.

References

Limb, M. (2013) Current financial pressures are worst ever, say NHS chiefs, BMJ, Jun 3, 346. f3616.

Mascharenas, M., Nash, Z., and Nathan, B. (2013) Letter: NICE promises on infertility and caesarean section are unmet, BMJ, Jun 18, 346.

How “comprehensive” is the NHS? Or “Something’s gotta give”?

Many in the discussion would wish you to concentrate on the phrase, “free-at-the-point-of-use”. This is the idea that you a patient does not pay for any treatment.

Many also do not understand the Health and Social Care Act (2012). There are many in the social media at large who feel that the NHS needs to face change in improving the service, and indeed point to crises within the NHS as examples of a failing service. It is critical that the NHS can learn from its mistakes, in terms of its operations, strategy and leadership. However, the Act’s primary purpose is not about that. I simply do not understand why the media, and notably the BBC, have been ‘asleep on the job’, in explaining what these £2bn reforms were about. The most common explanation is that the Act is incomprehensible. As a law student, it is perfectly comprehensible, but I would say that? The Act abolishes a number of important national authorities, such as the National Patient Safety Agency and the Health Protection Authority, but it legislates for a much greater number of private companies to do NHS functions in the name of the NHS. This means that ‘market forces’ can lead to distortions in provisions of healthcare, determined by the individual business plans of the companies involved. It is therefore a “supplier-led market”. In the high street, neoliberal forces have seen less profitable sectors such as immigration, housing and asylum, struggling compared to their City counterparts, corporate finance and the such like. Therefore, the critical issue is how “comprehensive” the NHS is.

On top of this, it is impossible to ignore the impact of the drive for ‘efficiency savings’. In 2009, Sir David Nicholson was reported of requiring such savings as below:

NHS trusts will have to deliver between £15 billion and £20 billion in efficiency savings over three years from 2011 to 2014, David Nicholson, the NHS chief executive, told health service finance directors in a speech delivered behind closed doors.

The steep cuts would be equivalent to up to six per cent of the current NHS budget.

Health trusts which fail to deliver the required savings could face tough new penalties following a review by the Department of Health of its enforcement regime.

The definition of “comprehensive” in the Oxford English Dictionary is indeed a useful starting point, essentially described as “including or dealing with all or nearly all elements or aspects of something“:

“Comprehensive” therefore means for most people “all” or “nearly all”, and it’s a matter of interpretation what “nearly” is. This “nearly” aspect has been a slow-burn in policy, for example: “Labour’s national policy forum will debate a draft document on the NHS which contains references to a “largely” comprehensive and “overwhelmingly” free service.” In March 2011, the NHS published its NHS Constitution, and a leading guiding principle is:

The NHS provides a comprehensive service, available to all irrespective of gender, race, disability, age, sexual orientation, religion or belief

This non-discriminatory aspect of provision of healthcare therefore emphasises equality.

It is therefore disingenious that a campaigning issue that individuals maintain that, after implementation of these costly reforms, that the NHS will still be ‘free-at-the-point-of-use’, as that ignores the comprehensive point. Colin Leys in the Guardian has already highlighted this as an issue in the Guardian:

Under the bill the range of what is available for free seems certain to contract further. Commissioning groups will have fixed budgets. The for-profit “support organisations” that are being lined up to do most of the commissioning for them will have a strong incentive to limit costs, and therefore the treatments to be paid for. CCGs also look likely to be free to decide that some treatments recommended by hospital specialists are “unreasonably” expensive, and refuse to pay for them, as health maintenance organisations do in the US.

A core of free NHS services will remain, but they will be of declining quality, because for-profit providers will cherry-pick the most profitable services. NHS hospitals will be left with the more costly work, so staffing levels and standards of care will be forced down and waiting times will get longer. To be sure of getting good healthcare people will increasingly take out private insurance, if they can afford it. At first most people will take out the cheaper insurance plans now on offer that cover just what is no longer free from the NHS, but gradually insurance for most forms of care will become normal. The poor will be left with a limited package of free services of lower quality.

What is available on the NHS should be determined nationally, in a transparent and democratic way, not by unelected local bodies. The bill will allow the secretary of state to deny responsibility when good, comprehensive, free care has become a thing of the past.

There are indications that services are being “scaled back”. For example, there have latterly been reports of impact on hearing services, for example:

NHS hearing services are being scaled back in England, an investigation by campaigners suggests.

Data obtained by Action on Hearing Loss from 128 hospitals found more than 40% had seen cuts in the past 18 months.

In particular, the study found evidence of rises in waiting times and reductions in follow-up care.

The report is the latest in a growing number to have suggested front-line care is being rationed as the health service struggles with finances.

The NHS is in the middle of a £20bn five-year savings drive.

The political question is, of course, whether the public accepts the need to ‘scale back’ these services and doesn’t care about the service being entirely comprehensive; or whether Labour (or indeed any party) should simply give up on an inspiration for totality in the service. A film once starred Marilyn Monroe entitled “Something’s Gotta Give”, and now that the first major step has been taken in ‘liberalising’ the NHS to any qualified provider, it is perhaps more necessary than ever to admit there is no guarantee at all on the NHS provision being close to “comprehensive”, unless the NHS Commissioning Board gives clear and precise details which services have been cut and where. This is going to be increasingly significant as a mature discussion about rationing gathers momentum too.

Above all, it seems now essential that local respondents are allowed to offer feedback into this clinical decision process, for example as demonstrated recently in the Lewisham situation, otherwise localism is a complete farce.

Integration: a completely personal view

I feel that there is a lot of “hype” concerning integration of health and social care services, and I do not wish to reinvent the wheel by offering the same definitions and the same process maps.

However, I think the challenge is at a number of different levels. First of all, I think that there needs to be a cultural change whereby the medical and social care cultures meet somewhere. Moving towards a culture where the health and social care needs, both medical and welfare, meet requires some understanding of why and how the cultures are different. There are a number of contributing factors, but it is hard to escape from the inherent difference in organizational structures and functions, personnel, training, budgets, to name but a few. Again, this brings up the problem of the extent to which managers can manage in the NHS without direct experience of how patients are clinically managed in the NHS.