Imagine you are a 45 year old lady who goes to see a GP with a lump on the breast.

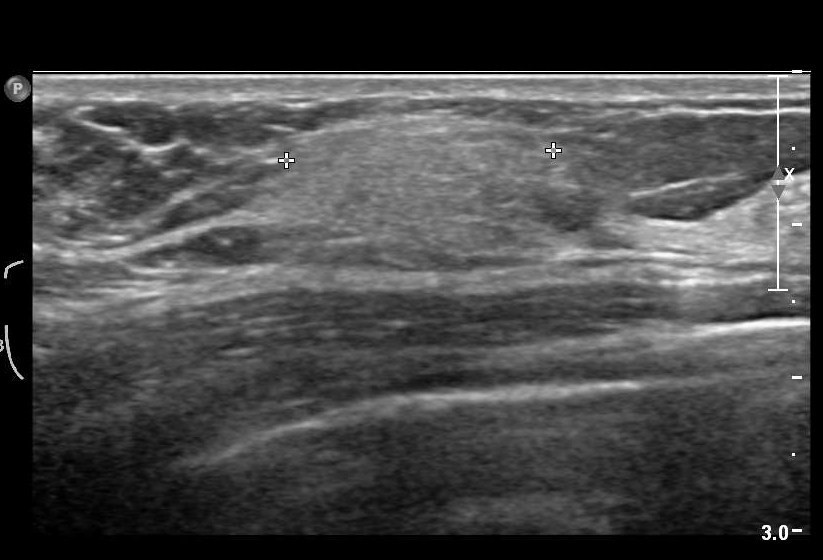

Just pretend the lump on the breast is not a sinister cancer, but a small harmless fatty collection of fatty cells called a lipoma.

Would you appreciate that GP labelling you as having breast cancer because of a Government target to improve the number of diagnoses of breast cancer nationally?

Whilst it might be good for that GP ‘hitting the target’, the GP is certainly ‘missing the point’, as he or she has inadvertently given the patient much distress through the misdiagnosis.

In medicine of course you do not necessarily need to progress to a surgical biopsy to lead to a confident diagnosis. It happens that it is relatively most unusual for a diagnosis of dementia to warrant a neurosurgical brain biopsy unless it might be for a rarer condition such as Variant Creutzfeld Jacob, or a potentially treatable cerebral vasculitis (inflammation of the brain).

It is known that a sizeable minority of people we think have dementia do not actually turn out to have dementia on post mortem. Indeed, according to Professor Seth Love? Department of Neuropathology, University of Bristol Institute of Clinical Neurosciences, “In most published series, the accuracy of clinical diagnosis of the different diseases that cause dementia is of the order of 70–80%.”

The definitive diagnosis of dementia is achieved post mortem.

Whilst it is laudable that there is a strong drive to improve the diagnosis of rate of dementia in England, it is absolutely imperative that this diagnosis should be reliable. Otherwise the scenario arises where a 85 year-old man who lives on his own, recently widowed, suffering from profound clinical depression can inadvertently get mislabelled as having a dementia, and this diagnosis in itself makes him even more depressed.

In recent years, large corporate-acting charities have been largely responsible for touting the concept of identifying people ‘before they have the disease’, for example overweight people who are likely to develop type II diabetes. Likewise, in dementia, professionals have received massive pressure from non-professionals for finding that ‘pot of gold’ of people who most likely might develop dementia. Despite much obfuscation and smoke and mirrors, it is known reliably now that the ‘mild cognitive impairment’, of ‘minor’ dementia-like symptoms, is not that pot of gold, as many individuals with this condition never go onto develop dementia.

But having a roadside MOT in primary care has been argument popularised by large charities and politicians who have been successfully lobbied by them. Without adequate resources going into service provision or training of people in the service, this approach runs the risk of creating an unprecedented demand for people who are in fact ‘worried well’.

Robert Aronowitz (2009) argues that risk of disease and actually having the disease have become conflated.

“Imagine two women, one who is suffering from breast cancer and the second, “merely” at risk for the disease. The first woman is fifty-eight years old. Two years earlier, she detected a lump in her left breast. After an aspiration biopsy revealed cancerous cells, she had a lumpectomy and removal of lymph nodes in her armpit (none of which contained cancer), followed by a course of local radiation and then six months of chemotherapy. After this acute treatment, she was put on a five-year course of the “anti-estrogen” Tamoxifen. She now closely follows developments in breast cancer. At the moment, she is concerned about whether to start another kind of hormonal therapy after her course of Tamoxifen ends and whether she should begin getting screening breast MRIs and/or more frequent mammography. For these and other questions, she frequently searches the web and attends meetings of breast cancer survivor and advocacy groups.”

“The second woman also is fifty-eight years old. She took birth control pills during her twenties, had her first child at age thirty-four, and, at the urging of her gynecologist, took supplementary estrogen pills starting at age fifty because of menopausal symptoms and to prevent heart disease and osteoporosis. A few years later her doctor told her to stop taking these pills because new medical evidence had conclusively shown that their risks—especially an increased risk of developing breast cancer—outweighed their putative benefits. Since age forty, she has been getting annual mammograms. Four years ago, she had an abnormal mammogram, which led to an aspiration biopsy that did not show cancer. Fearful of developing breast cancer, she is attentive to media reports and periodically browses the Internet for new information on cancer prevention. She has seen direct-to-consumer advertisements for Tamoxifen as a preventive measure for women at high risk of breast cancer. She understands that she has multiple risk factors for breast cancer, such as being middle-aged, being postmenopausal, having had her first child after thirty, having earlier used hormone replacement therapy, and having a history of a benign breast biopsy. She has sought advice from friends, doctors, and breast cancer advocacy groups about whether to take Tamoxifen and/or to find other means of reducing her risk of breast cancer.”

“At present, the first woman does not experience any symptoms of cancer but nonetheless undergoes intensive surveillance, has concerns about the long-term effects of previous treatments, and faces the future with caution. The experience of the second women is not very different. She may well decide to take Tamoxifen to prevent breast cancer. Like the first woman, she undergoes frequent surveillance and faces the future with caution. Both women face an array of similar choices and seek guidance in similar places. They share fears for the future, feelings of randomness and uncertainty, and pressures for self-surveillance. Both seek ways to regain a sense of control and face difficult decisions about preventive treatment and consumption. They are part of a larger breast cancer continuum, both in how scientists understand breast cancer and as a mobilized group for advocacy, fund-raising, and awareness (Klawiter 2002).”

In dementia, people who might be ‘at risk’ are those with strong genetic risk factors, or have a particular constellation of risk factors (hypothetically food intake low in zinc or high in cholesterol etc.) Industries allied to medicine would love to open up new markets by finding these people and offering them treatments early on. However, the drugs currently used to treat Alzheimer’s disease only impact on symptoms for some for a short while, and there is no consistent robust evidence that they slow down the disease course in humans.

In October 2014, I will be presenting data in the Alzheimer’s Europe conference in Glasgow about how precise identification of people most likely to develop dementia will lead those people to have insurance premiums which go through the roof, in a private insurance system, compared to a system where we all pool risk in the National Health Service.

I blogged on this study originally here.

The direction of travel for dementia with influences from private industry is a malign one. It consists of actively seeking out people are who are yet to develop dementia at the risk of completely ignoring the needs of the current cohort of people trying to live well with dementia. The pharmaceutical companies have been spectacular in the minimisation of failures over the last few decades in therapeutic treatment of dementia, and the current case finding approach in the English national health service has the potential to produce as much distress as much benefit.

But people have been warning about major fault lines in our dementia policy, correctly, for some time. See, for example, the excellent work by Margaret McCartney and Martin Brunet.

We can’t go on like this. Identifying people who “might” have dementia is simply not good enough. A properly funded National Health Service, where we are all “in it together”, where the concerns of professionals are listened to as well as the spokesmen of the new ‘dementia economy’, is a necessary start. Besides, the service for post-diagnostic support for those individuals who have been correctly identified as having a dementia needs to be far better resourced and organised so that people don’t feel they are being sent from pillar to post.