Home » Posts tagged 'screening'

Tag Archives: screening

Identifying people who “might” have dementia is simply not good enough

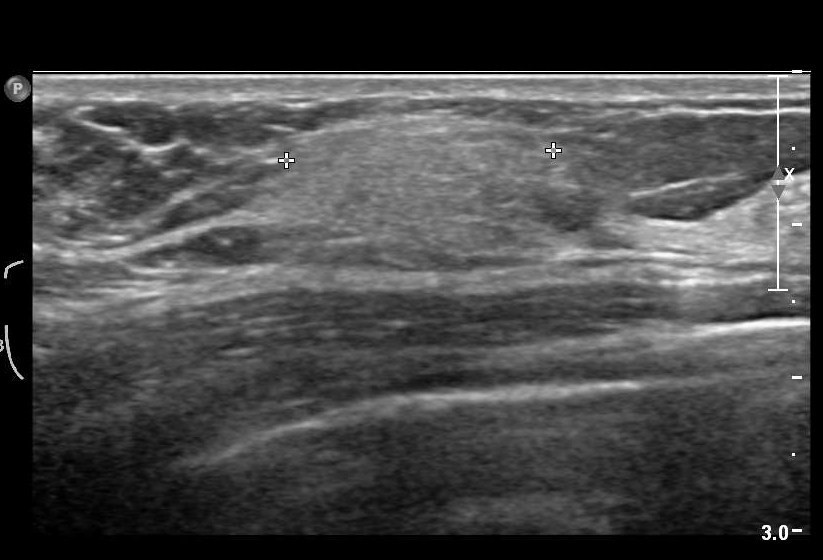

Imagine you are a 45 year old lady who goes to see a GP with a lump on the breast.

Just pretend the lump on the breast is not a sinister cancer, but a small harmless fatty collection of fatty cells called a lipoma.

Would you appreciate that GP labelling you as having breast cancer because of a Government target to improve the number of diagnoses of breast cancer nationally?

Whilst it might be good for that GP ‘hitting the target’, the GP is certainly ‘missing the point’, as he or she has inadvertently given the patient much distress through the misdiagnosis.

In medicine of course you do not necessarily need to progress to a surgical biopsy to lead to a confident diagnosis. It happens that it is relatively most unusual for a diagnosis of dementia to warrant a neurosurgical brain biopsy unless it might be for a rarer condition such as Variant Creutzfeld Jacob, or a potentially treatable cerebral vasculitis (inflammation of the brain).

It is known that a sizeable minority of people we think have dementia do not actually turn out to have dementia on post mortem. Indeed, according to Professor Seth Love? Department of Neuropathology, University of Bristol Institute of Clinical Neurosciences, “In most published series, the accuracy of clinical diagnosis of the different diseases that cause dementia is of the order of 70–80%.”

The definitive diagnosis of dementia is achieved post mortem.

Whilst it is laudable that there is a strong drive to improve the diagnosis of rate of dementia in England, it is absolutely imperative that this diagnosis should be reliable. Otherwise the scenario arises where a 85 year-old man who lives on his own, recently widowed, suffering from profound clinical depression can inadvertently get mislabelled as having a dementia, and this diagnosis in itself makes him even more depressed.

In recent years, large corporate-acting charities have been largely responsible for touting the concept of identifying people ‘before they have the disease’, for example overweight people who are likely to develop type II diabetes. Likewise, in dementia, professionals have received massive pressure from non-professionals for finding that ‘pot of gold’ of people who most likely might develop dementia. Despite much obfuscation and smoke and mirrors, it is known reliably now that the ‘mild cognitive impairment’, of ‘minor’ dementia-like symptoms, is not that pot of gold, as many individuals with this condition never go onto develop dementia.

But having a roadside MOT in primary care has been argument popularised by large charities and politicians who have been successfully lobbied by them. Without adequate resources going into service provision or training of people in the service, this approach runs the risk of creating an unprecedented demand for people who are in fact ‘worried well’.

Robert Aronowitz (2009) argues that risk of disease and actually having the disease have become conflated.

“Imagine two women, one who is suffering from breast cancer and the second, “merely” at risk for the disease. The first woman is fifty-eight years old. Two years earlier, she detected a lump in her left breast. After an aspiration biopsy revealed cancerous cells, she had a lumpectomy and removal of lymph nodes in her armpit (none of which contained cancer), followed by a course of local radiation and then six months of chemotherapy. After this acute treatment, she was put on a five-year course of the “anti-estrogen” Tamoxifen. She now closely follows developments in breast cancer. At the moment, she is concerned about whether to start another kind of hormonal therapy after her course of Tamoxifen ends and whether she should begin getting screening breast MRIs and/or more frequent mammography. For these and other questions, she frequently searches the web and attends meetings of breast cancer survivor and advocacy groups.”

“The second woman also is fifty-eight years old. She took birth control pills during her twenties, had her first child at age thirty-four, and, at the urging of her gynecologist, took supplementary estrogen pills starting at age fifty because of menopausal symptoms and to prevent heart disease and osteoporosis. A few years later her doctor told her to stop taking these pills because new medical evidence had conclusively shown that their risks—especially an increased risk of developing breast cancer—outweighed their putative benefits. Since age forty, she has been getting annual mammograms. Four years ago, she had an abnormal mammogram, which led to an aspiration biopsy that did not show cancer. Fearful of developing breast cancer, she is attentive to media reports and periodically browses the Internet for new information on cancer prevention. She has seen direct-to-consumer advertisements for Tamoxifen as a preventive measure for women at high risk of breast cancer. She understands that she has multiple risk factors for breast cancer, such as being middle-aged, being postmenopausal, having had her first child after thirty, having earlier used hormone replacement therapy, and having a history of a benign breast biopsy. She has sought advice from friends, doctors, and breast cancer advocacy groups about whether to take Tamoxifen and/or to find other means of reducing her risk of breast cancer.”

“At present, the first woman does not experience any symptoms of cancer but nonetheless undergoes intensive surveillance, has concerns about the long-term effects of previous treatments, and faces the future with caution. The experience of the second women is not very different. She may well decide to take Tamoxifen to prevent breast cancer. Like the first woman, she undergoes frequent surveillance and faces the future with caution. Both women face an array of similar choices and seek guidance in similar places. They share fears for the future, feelings of randomness and uncertainty, and pressures for self-surveillance. Both seek ways to regain a sense of control and face difficult decisions about preventive treatment and consumption. They are part of a larger breast cancer continuum, both in how scientists understand breast cancer and as a mobilized group for advocacy, fund-raising, and awareness (Klawiter 2002).”

In dementia, people who might be ‘at risk’ are those with strong genetic risk factors, or have a particular constellation of risk factors (hypothetically food intake low in zinc or high in cholesterol etc.) Industries allied to medicine would love to open up new markets by finding these people and offering them treatments early on. However, the drugs currently used to treat Alzheimer’s disease only impact on symptoms for some for a short while, and there is no consistent robust evidence that they slow down the disease course in humans.

In October 2014, I will be presenting data in the Alzheimer’s Europe conference in Glasgow about how precise identification of people most likely to develop dementia will lead those people to have insurance premiums which go through the roof, in a private insurance system, compared to a system where we all pool risk in the National Health Service.

I blogged on this study originally here.

The direction of travel for dementia with influences from private industry is a malign one. It consists of actively seeking out people are who are yet to develop dementia at the risk of completely ignoring the needs of the current cohort of people trying to live well with dementia. The pharmaceutical companies have been spectacular in the minimisation of failures over the last few decades in therapeutic treatment of dementia, and the current case finding approach in the English national health service has the potential to produce as much distress as much benefit.

But people have been warning about major fault lines in our dementia policy, correctly, for some time. See, for example, the excellent work by Margaret McCartney and Martin Brunet.

We can’t go on like this. Identifying people who “might” have dementia is simply not good enough. A properly funded National Health Service, where we are all “in it together”, where the concerns of professionals are listened to as well as the spokesmen of the new ‘dementia economy’, is a necessary start. Besides, the service for post-diagnostic support for those individuals who have been correctly identified as having a dementia needs to be far better resourced and organised so that people don’t feel they are being sent from pillar to post.

Have Big Pharma undermined the case for screening through their grip on dementia policy?

Certain General Practitioners are ‘on heat’ as they take great delight in identifying that dementia does not meet current screening criteria, but they are missing their targets of creating maximum fuss but totally missing the point. In their narrow world, they define “benefit” as a treatment such as a magic bullet. “Benefit”, I believe even under the Wilson and Jungner (1968) construct, can mean something much wider, and ultimately the authors give a very big sense of this being for the benefit of the person or patient not the benefit of the physician. We simply have a lack of evidence base for living well with dementia, due to charities which focus on cure, care and prevention. Without this evidence, we cannot say, any of us, however big or small in the medical establishment or outside, that there’s “no benefit”. Carts and horses spring to mind. This is a good case of medical hierarchy being utterly irrelevant to ‘who is right’, and more importantly ‘what is right’ for the person trying to live well with dementia after his or her diagnosis.

There’s no doubt about it. There’s been an intense policy drive to encourage people with memory problems ‘to present themselves’ for early diagnosis, and various devices have been used to encourage this, including participating in drug research (hence the extreme media publicity for a ‘drive for a cure’). Screening for dementia is a pot of gold for the ‘dementia health economy’, even more so than “Dementia Friends”, as it produces a new market for people who might be eligible for a drug treatment that ‘stops dementia in its tracks’ one day. But some of the confusion has come from the extent to which the screening criteria embraces early symptomatic persons as well as completely asymptomatic ones, and official guidelines, derived from Wilson and Jungner (1968), are not solely for early symptomatic people. But the irony is that the relentless focus on the medical model, without resources going into demonstrating the efficacy of wellbeing interventions as a way of ameliorating morbidity in dementias, including Alzheimer’s Disease, may be ultimately stopping the screening criteria being met, denying access of Big Pharma to this pot of gold. But the way in which Big Pharma has a stranglehold on big charities and research programmes, epitomised by the recent G8 dementia summit in Lancaster House frontloading personalised medicine, could be entirely to blame.

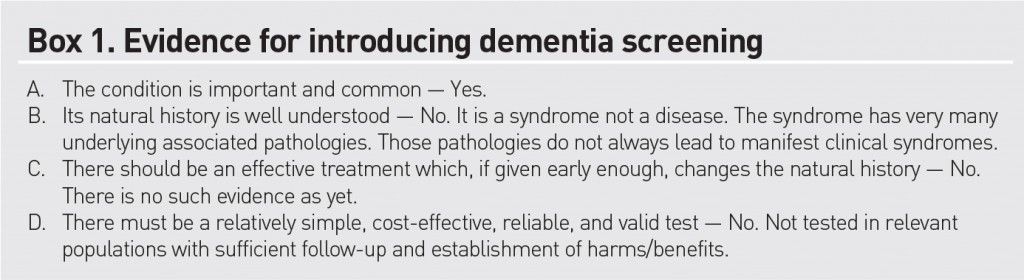

Various intellectual frameworks have, for example, been proposed for the screening of dementia in primary care outside of this jurisdiction. For example, this scheme appeared in the following paper.

The UK NSC policy on Alzheimer’s Disease screening in adults is in fact clear. A systematic population screening programme is not recommended. The National Screening Committee criteria for appraising the viability, effectiveness and appropriateness of a screening programme are based on the criteria developed by Wilson and Jungner in 1968 and address the condition, the test, the treatment and the screening programme. The need to refine them in the genomic age is illustrated in this statement from WHO in 2008. I have no intention of discussing the usual issues of screening/early detection, such as the distress caused by a false diagnosis, described elegantly elsewhere.

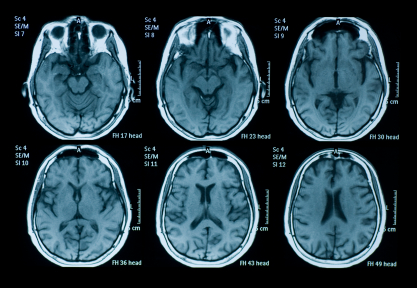

There is no doubt that the drives for screening at all under standard criteria suffer from a lack of inexpensive test which is sufficiently sensitive and specific – but this might be a temporary situation, and might be ultimately resolved one day with the correct ‘mix’ of questions, say in testing a wide range of neurocognitive functions. What is clearly untenable is sticking a large needle into the backs of all people who might be at risk of developing dementia to collect cerebrospinal fluid for biomarkers, or doing expensive MRI scans on everyone (notwithstanding the known limitations of brain scans in making the dementia diagnosis.)

A significant stumbling block is that there should be evidence from high quality Randomised Controlled Trials that the screening programme is effective in reducing mortality or morbidity. Clearly, drugs in reducing mortality for Alzheimer’s disease, which is only one type of dementia, have been lacking. The conclusion that there have been no randomised controlled trials to show that a screening programme for Alzheimer’s disease would be effective in reducing mortality or morbidity. But in fairness there has NEVER been a drive to collect a robust body of information on the long term effects on living well with dementia from an early diagnosis of dementia. Nobody has wished to fund it. The data are lacking. Decades and millions at least have been chucked into the aim that the drugs which ‘don’t work’ (and in fact can have dreadful side effects).

It is interesting that the stumbling block is not the lack of pre-symptomatic stage, though interestingly the National Screening Committee never make reference to mild cognitive impairment, which people who do not understand the evidence incorrectly refer to as ‘pre-dementia’. It is argued, for example, that during the pre-symptomatic period there is a gradual loss of axons and neurons in the brain and at a certain threshold the first symptoms, typically impaired memory for events and facts appear.

And it’s a useful context to think about the ethos in which the Wilson and Jungner criteria should be applied? Wilson and Junger themselves used the term ‘principles’ for ‘ease of description rather than from dogma’. It is unlikely that any screening programme will be able to fulfil all of these criteria to everyone’s satisfaction in any case. The question therefore arises as to whether each criterion has equal merit, or whether there is a hierarchy of importance using this construct. Wilson and Junger felt that ‘of all the criteria that a screening test should fulfil, the ability to treat the condition adequately, when discovered, is perhaps the most important’.

And the build up of these criteria emphasise the clinical method, although the literature in reviewing data results as a desktop exercise is massive. Jungner and Wilson themselves state:

“The medical history is very important, and can be obtained by appro- priate questionaries. It has been reported from many investigations that the medical history and the physician’s physical examination make the greatest contribution to the diagnosis. However, most of the diagnoses are then known before the screening procedures. How much medical value is afforded by the notation of earlier known disease remains to be seen. Obviously, the information is most useful the first time an examination is undertaken. The history is of immense value and the advantage of questionaries is great.”

Jungner and Wilson refer to their review of relevant papers in the 1950s, and their criticisms of case-finding in the absence of seeing the big picture are well known from close reading of their paper.

They cite:

“Some of the chief points made in these papers were:

(1) Case-finding by multiple screening is a technique well suited to public health departments, whose role is changing.

(2) Provision for diagnosis, follow-up and treatment is vitally impor- tant; without it case-finding must inevitably fall into disrepute.

(3) Tests must be validated before they are applied to case-finding; harm may result to public health agencies’ relationships with the public (not to mention the direct harm to the public), and with the medical profession, from large numbers of fruitless referrals for diagnosis.”

Putting all your eggs in the investigations basket has been a discredited approach in the past in neurology. In one particular review of studies, 82% percent (54/66) of investigators reported discovering incidental findings, such as arteriovenous malformations, brain tumours, and developmental abnormalities. Auhors of that particular paper (J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2004;20:743–747) proposed that guidelines for minimum and optimum standards for detecting and communicating incidental findings on brain MRI research are needed.

So is it viable to do backdoor collection of data to identify cases? Wilson and Jungner indeed describe this failed approach in diabetes detection, according to Joslin and colleagues this work goes back to 1909, when Barringer had reported the findings on over 70 000 persons examined for life insurance purposes. Wilson and Jungner themselves noted that, “Despite all this work it is still difficult to evaluate the results in terms of benefit to the populations screened. Some of the criteria for case-finding discussed above remain unsatisfied.”

So this lack of intelligent thinking from the medical profession has come full circle many years after the original Wilson and Jungner paper. General Practitioners increasingly now recognise the importance and benefits of a timely and explicitly disclosed dementia diagnosis. But it’s argued that there are many barriers to diagnosis at both the physician and patient level. Barriers at the physician level include time constraints, insufficient knowledge and skills to diagnose dementia, therapeutic nihilism and fear to harm the patient.

But it’s impossible to skirt around the basic ‘rules’ of medical ethics, much as non-clinicians in the dementia economy might like to. These include respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficience and justice. And doing things without a patient’s consent, if they have mental capacity, is ethically offensive and legally could constitute assault or battery. This issue has been seen in coeliac disease previously, reported in a paper about a decade ago (Gut. Jul 2003; 52(7): 1070–1071):

“Although the investigational process for population screening and case finding may be the same, there is an important ethical difference between them. If a patient seeks medical help then the physician is attempting to diagnose the underlying condition (for example: patients with CD who present with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome). This would be classified as case finding and clearly it is the patient who has initiated the consultation and in some sense is consenting for investigation. Conversely, individuals (who are not patients) found to have CD through screening programmes, may have considered themselves as “well” and it is the physician or healthcare system that is identifying them as potentially ill.”

And these ethical concerns appeared originally in the mid 1980s with HIV testing. HIV is used as the “poster boy” in the drive for a cure for dementia, but it’s worth remembering the history of this situation too. Prior to an effective treatment, ethical concerns centred on the right of patients not to be tested, since an HIV diagnosis provided few medical benefits and posed serious risks of stigma and discrimination. The 3Cs were identified of “counselling, voluntary informed consent and confidentially”. But with the availability of ART drugs, there was accumulating evidence that ART can prevent transmission of HIV, strengthened public health arguments for scaling up testing. This led to a reformulation of guidelines, such as “Testing the gateway to prevention, treatment and care” when in 2007 WHO recommended PITC (provider?initiated counselling and testing)

Nevertheless, the primary care setting in England provides unique opportunities for timely diagnosis of dementia. It has just been reported that GPs will be given more leeway to use their clinical judgement in deciding when to offer dementia assessments under a revamp of the specifications for the controversial dementia case finding DES. Under the agreed changes, GPs will still be required to offer the assessments to the same ‘at-risk’ groups of patients on their list, but only if the GP feels it is ‘clinically appropriate’ and ‘clinical evidence supports it’. At-risk groups again include patients aged 60 and over with vascular disease or diabetes, those over 40 with Down’s syndrome, other patients over 50 with learning disabilities and patients with neurodegenerative disease.

And, this is broadly consistent with approaches from other jurisdictions. Case finding remains the preferred approach to identifying patients with dementia and Alzheimer disease, according Australian experts, after a US advisory body found insufficient evidence to support universal screening for cognitive impairment in older patients.

Professor Dimity Pond, professor of general practice at the University of Newcastle, agreed that there was insufficient evidence for screening. Professor Pond said further a false-positive diagnosis could also cause a lot of distress to the patient and their family. “It’s a huge diagnosis to be made — it causes their family to worry about the need to start activating power of attorney, selling the house and putting them in a nursing home.”

Wilson and Junger themselves do not, however, specify whether patients, a third party, or society as a whole, should prioritise importance, and the utilitarian part of this economics discussion is lacking in temporal and geographical jurisdiction (in the same way that G8 hopes to meet its objectives likewise). J.S. Mill, in his celebrated essay “On Liberty”, argues that ‘there is no one so fit to conduct business, or to determine how or by whom it shall be conducted, as those who are personally interested in it’. But it is in reality difficult for an individual patient to be objective as to whether his/her health problem is more important than that of another patient or whether he/she deserves scarce resources in preference to others: it is impossible for an individual patient to make that comparison because of patient confidentiality, for example.

And policy makers need to be able to justify why memory problems are sufficient to trigger a particular care pathway, when a cough does not necessarily trigger full investigations for emphysema, or a headache does not trigger necessarily a full work-up for a brain tumour. The general rule for a ‘care pathway’ is “treating the right patient right at the right time and in the right way.”

I feel a fixation on ‘benefit’ as defined through the prism of the Pharma part of the health economy has led to a wilful neglect for wanting to find any beneficial outcomes in wellbeing from a timely diagnosis, such as improved design of the home, design of the built environments, and access to advocacy. But ultimately, regardless of the health economy and the lack of proper scrutiny of the issue, it is persons with dementia and their caregivers who I feel are suffering most, at the hands of the large charities and Big Pharma. GPs and medics are simply unable to say there’s “no benefit” for finding cases of dementia, whether it is screening or not, if the evidence base on living well with dementia is simply absent. Try to put the horse before the cart next time.

Health screening: corporates, the third sector, the NHS and the media “in it together”? BBC One’s “Long Live Britain”

The All Party Parliamentary Group Primary Care & Public Health published yesterday their ‘Inquiry Report into the Sustainability of the NHS “Is Bevan’s NHS under Threat?”‘. In their excellent report, they provided that “Preventative illnesses are overwhelming the NHS; illnesses caused by obesity, smoking, alcohol and lack of exercise. Diabetes, for example takes up 10% of the NHS budget, of which 90% is spent on dealing with preventable complications.”

The Faculty of Public Health response was follows:

“The need to treat lung cancer is waste – smoking cessation works and is far more cost effective at prolonging life than treatment for lung cancer. The need to treat heart disease is a waste – increasing physical activity levels, stopping smoking, improving diet are all preferable and cheaper. Treating measles is a waste – increasing vaccination uptake rates is more efficient; every case of HIV is a waste when it is easily preventable. There are barriers to smoking cessation (quality of services, access to services for vulnerable groups) as well as things that can be done to prevent people smoking in the first place (standardised tobacco packaging). There are barriers to preventing heart disease – transport systems and public open space that do not encourage incidental physical exercise; the availability of cheap high fat / salt / sugar food actively marketed to vulnerable populations (e.g. children); smoking (see above).”

Two issues have dominated the headlines in politics and public health this week; one is the issue of standardised packaging of cigarettes and the other is minimum alcohol pricing. A new BBC One two-part series, Long Live Britain, claims to be an “one-off, record-breaking televised event that will challenge the way we tackle three of Britain’s biggest preventable diseases.” On Saturday 25 May, Long Live Britain says it “will attempt to host Britain’s biggest-ever health screening, potentially testing thousands of possible undiagnosed sufferers for the three secret killers that collectively kill 200,000 each year and affect an estimated 11 million people each year – Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and liver disease. Presented by Julia Bradbury, Phil Tufnell and Dr Phil Hammond (@drphilhammond), it is claimed that, “the fascinating results will be screened on BBC One over one night in early summer.”

However, this is a delicate issue in reality. A group of practising Doctors have set up a website, Dr Pete Deveson (GP in Epsom, Surrey) (@PeteDeveson) , Dr Margaret McCartney (GP in Glasgow) (@mgtmccartney), Dr David Nicholl (Consultant Neurologist in Birmingham) (@djnicholl), Dr Jonathon Tomlinson (GP in Hackney, London) (@mellojonny), and and Professor Charles Warlow (Emeritus Professor of Medical Neurology University of Edinburgh) because they are concerned that the promotion of private screening tests in the UK is potentially unfair to people reading many of their adverts. They indeed have complained to the Advertising Standards Authority and the General Medical Council. Some changes have been made to the adverts after their complaints (see here and here. Clearly adequate choice can only be made on complete and accurae information.

Screening is a complicated issue. Prostate cancer is a good example. If a man is showing none of the symptoms associated with Prostate Cancer why should he consider having a screening? GP Dr Pete Deveson and Dr Tony Rudd, who is a consultant stroke physician, have both publicly voiced their concerns over private health checks. Margaret McCartney (above) was written passionately on this issue in the Guardian:

“The NHS offers many screening programmes, from the heelprick test for newborn babies to breast screening for women over 50. But screening – testing well people as opposed to people who already feel unwell or who have symptoms, like a lump, or palpitations – always has the potential to harm, and is a constant balance of pros and cons. There is a risk of false positives, false negatives and false reassurance, and the problem of sometimes giving people a diagnosis they don’t need, or subjecting them to treatment they won’t benefit from. Noninvasive tests may cause few hazards, but the way the knowledge from a positive or negative scan is used may result in harm to the patient for no benefit.

We’ve seen this in prostate cancer screening: initial enthusiasm for PSA (prostate-specific antigen) screening was followed by the realisation that around a third of men operated on would suffer impotence as a result and a fifth would have incontinence.

These might be acceptable risks if the treatment was death-delaying, butmost prostate cancers don’t kill and the evidence suggests that PSA screening does not reduce death rates.

This led Richard Albin, who discovered PSA, to tell the New York Timesthat screening for it had been a “public health disaster” in the US.

So screening is often counterintuitive and harmful. Because of these inherent problems, people need to make good choices about whether to be screened based on evidence. We know, for example, that when men are given better information about PSA screening, fewer want it.”

Screening has not been advocated for dementia, but this is ripe for corporate profiteering (and third sector colleagues who wish to be part of this agenda.) In an outstanding article published in British Journal of General Practice, Prof Carol Brayne and colleagues tackle this issue head on. Carol Brayne identifies the possible efficacy of ‘awareness’ campaigns in ‘generating fear’, and elaborates on these concerns:

“Turning to the private sector. It is quite possible that considerable ‘market’ can be generated through capitalisation of fear of dementia and cognitive decline. Direct-to-consumer advertising already exists for cancer (specific insurance schemes) and stroke (carotid and risk screening). Taking the example of stroke risk ‘screening’, individuals may receive, through population listings, materials that promote testing in centres sometimes hosted by primary care settings, which gives an apparent endorsement that this is evidenced practice. Could this happen with cognition? It seems likely, including the online potential. Does this matter? It depends on the outcome of the testing. If positive in some way where will these individuals turn for support? How much investigation will reassure them? How many people will be tested unnecessarily and for those who are identified as having a problem will there be sufficient resources to support them? In a publicly-funded system this will fall to their GP, who will therefore have less time for those who attend with existing concerns. In a private model these individuals may seek help elsewhere, paying for imaging and further tests. These may or may not provide reassurance or further indication of problems, but doing such tests is not, at present, justified on the basis of evidence. For some a remediable condition may be found, but as with general health screening, it will be impossible to say who has been harmed and who helped by such efforts.”

Brayne and colleagues do not feel that dementia fits the traditional Wilson-Jungner criteria for screening:

Either way, it is beginning to become clear, pursuant to an Act of parliament which enabled the outsourcing and award of contracts to the private sector in the National Health Service, and where the income in the NHS can come from private sources in up to 50%, screening is yet another issue which can be gamed by the private sector. How much the media wishes to have a genuine debate about raising awareness of clinical issues, as indeed is the agenda of the Faculty of Public Health, or gets embroiled in complex rent seeking behaviour for profitability or surplus generation of corporates and the third sector is a different matter. Of course, corporates, charities and the media, like the National Health Service, can have the best of intentions too.

Prof Alistair Burns, National Clinical Lead for Dementia, asks, “Do you have problems with your memory?”

It is widely anticipated that Scotland on Monday 3rd June 2013 will support England in calling for a ‘timely’ diagnosis for dementia, leading to an emphasis of person-centred care. The issue of how that diagnosis is made is therefore alive and well.

A G.P. is of course is incredibly busy. It is possibly the hardest job in medicine. In asking patients in a General Practice whether they are aware of memory problems, it’s like to looking for any horses once they have bolted. In terms of English policy, at least an attempt to find these bolted horses is presumably welcome, given that the general impression is that we are missing many horses bolting under our very eyes.

The question which Prof Burns proposes that Doctors in passing might ask is,

“Do you think you have any problems with your memory?”

For an overview of the complexity of the dementias, I can recommend the excellent chapter 24.2.2 by Prof John Hodges from the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine. You can see it chapter-24-4-21. I am grateful to Prof Hodges for including my paper in his chapter on a diagnosis of a common form of dementia.

G.P.s consistently have warned that they are terrified about their patients being “scared” to see their G.P., in case this question pops up ‘on the sly’ and the possibility of dementia is raised publicly in the “confidential” medical notes. In theory, any of the disease processes can affect any parts of the brain, affecting any number of the cognitive functions of the brain, behaviour and personality according to the precise distributed neuronal networks affected. This means that memory might not be the presenting feature of a dementia at all; it could be visuospatial difficulties or apraxia, behavioural problems, or isolated problems with planning. This question of course assumes that the patient can communicate the answer, and it is possible even that the method in which the answer is executed, even if it is nothing to do with memory, reveals a substantial language impairment (for example, the progressive primary aphasias, e.g. Savage et al., 2013). A patient with early Alzheimer’s disease is very likely to report memory problems, in anterograde memory, and the purpose of a brief question of a GP in a busy clinic is to detect at a unrefined way possible glaring “diagnoses” of Alzheimer’s disease. Loss of cognitive function in the elderly population is a common condition encountered in general medical practice, and fairly precise clinical diagnosis is feasible (e.g. Knopman, Boeve and Petersen, 2003). An unfortunate theoretical problem exists that a patient does indeed have memory problems but the patient is unaware of them. In a seminal paper by Starkstein and colleagues (Starkstein et al., 2006), the authors reported on how unawareness of cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease is related might be related the severity of intellectual impairment, a phenomenon known as ‘anosognosia’.

The ideal is that a patient might report memory problems, when probed, but the question suffers from a lack of specificity. In other words, all sorts of people, even if they don’t have dementia, might at first answer “yes!” This inevitably will include what used to be called “the worried well”. Real memory problems could be caused by a whole manner of other conditions, as well as dementia, such as stroke, depression or an underactive thyroid. It could conceivably a “transient global amnesia”, and the exact aetiology of this is currently considered to be uncertain. A mild cognitive impairment (“MCI”) is a clinical diagnosis in which deficits in cognitive function are evident but not of sufficient severity to warrant a diagnosis of dementia (Nelson and O’Connor, 2008). In addition to presentations featuring memory impairment, symptoms in other cognitive domains (e.g. executive function, language, or visuospatial) have been identified. Indeed, in humans, heterogeneity in the decline of hippocampal-dependent episodic memory is observed during aging, and animal models now exist for this phenomenon (Foster, 2012).

There is also a problem that individuals with a dementia syndrome sometimes do not exhibit any memory problems. Indeed, as reviewed by Hornberger and Piquet (2012), over the last twenty years or so, however, the clinical view has been that episodic memory processing is relatively intact in the frontotemporal dementia syndrome; but it is perhaps also worth noting that these authors also note that recent evidence questions the validity of preserved episodic memory in frontotemporal dementia, particularly in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia, a progressive syndrome characterised in its early stages by changes in personality and behaviour, and which indeed gets confused with common adult psychiatric conditions (Pose et al., 2013). It is of course theoretically possible that individuals may have a subclinical form of dementia, where there are no florid memory symptoms for example, but there is an underlying cause (e.g. Morvan’s syndrome, a rare complex syndrome with antibodies to the potassium-channel gated complex producing a dementia involving cognitive problems (Loukaides et al., 2012)), or a paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis producing a dementia (Gultekin et al., 2010). Indeed, in the paraneoplastic dementias, mild cognitive deficits may present before a florid dementia or before the presentation even of the underlying malignancy, for which a full hunt might later then be instigated.

Full-blown screening on a national scale would fundamentally depend on finding a cheap test for finding individuals at risk of later developing the disease. Any quick question is immediately going to run into problems in that dementia is such a wide diagnostic group. Certainly, the question is not sufficient on its own. For example, in an appropriate patient, it might be sensible to ask if the patient has seen things which are not there (in the hope of identifying visual hallucinations as in diffuse Lewy Body Dementia, e.g. Gaig et al., 2011). Even for the most common type of dementia, there is a very active debate whether there might be a reliable prodromal or preclinical phase of Alzheimer’s disease, when changes are taking place even without overt symptoms. Molineuvo and colleagues (Molinuevo et al., 2012), consistent with previous findings, indeed suggest that the preclinical stage is biologically active and that there may be structural changes when amyloid is starting its deposition, reflected in changes in concentrations of markers in cerebrospinal fluid or cortical thickness.

Clearly, investing a lot of time, money and effort in using such techniques currently would be considered impractical in any booming economy (which we do not have), especially given that the cost-impact implications of managing patients with dementia in the community are unclear (Brilleman et al., 2013), and the very modest effects of treatments to improve memory such as the cholinesterase inhibitors have in fact been well known for some considerable time (Holden and Kelly, 2002). It might be attractive to think that MCI is a preclinical form of dementia of Alzheimer Type, but unfortunately the evidence is not there to back this claim up at present: only approximately 5-10% and most people with MCI will not progress to dementia even after ten years of follow-up (Mitchell and Shiri-Feshki, 2009). If one takes the point of view in that the existence of memory symptoms above a certain age might cause ‘alarm bells’ about the need for further investigation, such as specialist opinion about neuroimaging, cognitive psychometry, or even cerebrospinal fluid or brain biopsy (the latter conceivably in the case of cerebral vasculitis or prion disease), such an approach might be worthwhile. However, such a strategy is hugely dependent on the quality of clinicians in primary care and beyond in the NHS, where quality is not a function of economic competition. Quality of dementia care depends on a clinician’s aptitude in taking a targeted history, examination, investigations and management plan.

So, to all intents and purposes, this simple question is dirt cheap, but fails somewhat on specificity and sensitivity. And it all might be pretty innocent enough, if individuals with a genuine diagnosis of dementia are able to access routes enabling them to live well through person-centred care. However, as it is presented, this is potentially a ‘huge ask’ if politicians raise expectations, and do not allocate resources in primary care and specialist dementia and cognitive disorders clinics to match. While the reported underreporting of dementia in the community is not a trivial issue, the demands concerning adequate care of individuals successfully found to be identified with a dementia are likely to be substantial, and for which no convincing impact assessment data have curiously ever been published. Diagnosing lots of dementia might become somebody else’s problem for management if there are inadequate resources; and by that stage this current Government and key personnel might have even moved on, of course.

Please direct comments to Prof @ABurns1907 on Twitter, and not me, if you should like to contribute to this debate. Thank you.

References

Brilleman SL, Purdy S, Salisbury C, Windmeijer F, Gravelle H, and Hollinghurst S. (2013) Implications of comorbidity for primary care costs in the UK: a retrospective observational study, Br J Gen Pract, 63(609), pp. e274-82.

Foster, T.C. (2012) Dissecting the age-related decline on spatial learning and memory tasks in rodent models: N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in senescent synaptic plasticity, Prog Neurobiol, 96(3), pp. 283 – 303.

Gaig, C., Valldeoriola, F., Gelpi, E., Ezquerra, M., Llufriu, S., Buongiorno, M., Rey, M.J., Martí, M.J., Graus, F., and Tolosa, E. (2011) Rapidly progressive diffuse Lewy body disease, Mov Disord, 26(7), pp. 1316 – 1323.

Gultekin, S.H., Rosenfeld, M.R., Voltz, R., Eichen, J., Posner, J.B., and Dalmau, J. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis: neurological symptoms, immunological findings and tumour association in 50 patients, Brain, 123 (Pt 7), pp. 1481 – 1494.

Holden, M., and Kelly, C. (2002)) Use of the cholinesterase inhibitors in dementia, Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 8, pp. 89-96.

Hornberger M, and Piguet O. (2012) Episodic memory in frontotemporal dementia: a critical review, Brain, 135 (Pt 3), pp. 678-92.

Knopman, DS, Boeve BF, and Petersen RC. (2003) Essentials of the proper diagnoses of mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and major subtypes of dementia. Mayo Clin Proc, 78(10), pp. 1290-308.

Loukaides, P., Schiza, N., Pettingill, P., Palazis, L., Vounou, E., Vincent, A., aand Kleopa, K.A. (2012) Morvan’s syndrome associated with antibodies to multiple components of the voltage-gated potassium channel complex, J Neurol Sci, 312(1-2), pp. 52-6.

Mitchell, A.J., and Shiri-Feshki, M. (2009) Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia -meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 119(4), pp. 252-65.

Molinuevo, J.L., Sánchez-Valle, R., Lladó, A., Fortea, J., Bartrés-Faz, D., Rami, L. (2012) Identifying earlier Alzheimer’s disease: insights from the preclinical and prodromal phases, Neurodegener Dis, 10(1-4), pp. 158-60.

Nelson, A.P., and O’Connor, M.G. (2008) Mild cognitive impairment: a neuropsychological perspective, CNS Spectr, 13(1), pp. 56-64.

Pose, M., Cetkovich, M., Gleichgerrcht, E., Ibáñez, A., Torralva, T., and Manes F. (2013) The overlap of symptomatic dimensions between frontotemporal dementia and several psychiatric disorders that appear in late adulthood, Int Rev Psychiatry, 25(2), pp. 159-167.

Savage, S., Hsieh, S., Leslie, F., Foxe, D., Piguet, O., and Hodges, J.R. (2013) Distinguishing subtypes in primary progressive aphasia: application of the Sydney language battery, Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 35(3-4), pp. 208-18.

Imbalance of information has been a problem endemic in much of life recently

Had certain people at the BBC known about, and acted upon, the information which is alleged about Jimmy Savile, might things have turned out differently? George Entwhistle tried to explain yesterday in the DCMS Select Committee his local audit trail of what exactly had happened with the non-report by Newsnight over these allegations.

‘Information asymmetry’ deals with the study of decisions in transactions where one party has more or better information than the other. This creates an imbalance of power in transactions which can sometimes cause the transactions to go awry, a kind of market failure in the worst case. Information asymmetry causes misinforming and is essential in every communication process. In 2001, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to George Akerlof, Michael Spence, and Joseph E. Stiglitz for their “analyses of markets with asymmetric information.” Information asymmetry models assume that at least one party to a transaction has relevant information whereas the other(s) do not. Some asymmetric information models can also be used in situations where at least one party can enforce, or effectively retaliate for breaches of, certain parts of an agreement whereas the other(s) cannot.

In adverse selection models, the ignorant party lacks information while negotiating an agreed understanding of or contract to the transaction, whereas in moral hazard the ignorant party lacks information about performance of the agreed-upon transaction or lacks the ability to retaliate for a breach of the agreement. An example of adverse selection is when people who are high risk are more likely to buy insurance, because the insurance company cannot effectively discriminate against them, usually due to lack of information about the particular individual’s risk but also sometimes by force of law or other constraints. An example of moral hazard is when people are more likely to behave recklessly after becoming insured, either because the insurer cannot observe this behavior or cannot effectively retaliate against it, for example by failing to renew the insurance.

Joseph E. Stiglitz pioneered the theory of screening, and screening is a pivotal theme in both economics and medicine. In this way the underinformed party can induce the other party to reveal their information. They can provide a menu of choices in such a way that the choice depends on the private information of the other party.

Examples of situations where the seller usually has better information than the buyer are numerous but include used-car salespeople, mortgage brokers and loan originators, stockbrokers and real estate agents. Examples of situations where the buyer usually has better information than the seller include estate sales as specified in a last will and testament, life insurance, or sales of old art pieces without prior professional assessment of their value.

This situation was first described by Kenneth J. Arrow in an article on health care in 1963. The asymmetry of information makes the relationship between patients and doctors rather different from the usual relationship between buyers and sellers. We rely upon our doctor to act in our best interests, to act as our agent. This means we are expecting our doctor to divide herself in half – on the one hand to act in our interests as the buyer of health care for us but on the other to act in her own interests as the seller of health care. In a free market situation where the doctor is primarily motivated by the profit motive, the possibility exists for doctors to exploit patients by advising more treatment to be purchased than is necessary – supplier induced demand. Traditionally, doctors’ behaviour has been controlled by a professional code and a system of licensure. In other words people can only work as doctors provided they are licensed and this in turn depends upon their acceptance of a code which makes the obligations of being an agent explicit or as Kenneth Arrow put it “The control that is exercised ordinarily by informed buyers is replaced by internalised values”

In standard civil litigation, disclosure of information takes place between the two parties in standard proceedings, a party must disclose every document of which it has control and which falls within the scope of the court’s order for disclosure. Even if a party discloses a document, the other party is not entitled to inspect the document. Of course, this disclosure procedure might have effects in producing information imbalances, where it is important to see ‘the big picture’. Such a situation is the Leveson Inquiry, ultimately looking at how activities might be better regulated if appropriate (and by whom). The communications with the former News International chief executive and the News of the World editor-turned spin doctor, Andy Coulson, were reportedly kept from the hearings into press standards after the Prime Minister sought legal advice. Labour said that David Cameron, the UK Prime Minister, must make sure that “every single communication” that passed between him and the pair be made available to the inquiry and the public. The cache runs to dozens of emails including messages sent to Mr Coulson while he was still an employee of Rupert Murdoch, according to reports. It was described by sources as containing “embarrassing” exchanges with the potential to cast further light on Mr Cameron’s relationship with two of Mr Murdoch’s most senior executives. However, Downing Street was said to have been advised that it was not “relevant” to the Leveson inquiry as the documents they contained fell outside its remit, according to The Independent.

Information imbalances, for us on a more daily basis, have a direct effect on the consumer-supplier relationship of the econy, We have been told to absurdity on how much of our problems as consumers would be solved if we could simply ‘switch easily’ between energy suppliers. In a sense, either there should be far less competition (i.e. the whole thing merges into one state supplier, reducing absurdities in a few suppliers all providing the same product at a high price, similar to exam boards currently), or there should be far more competition (there is currently an oligopolistic situation in many markets, which would be greatly ameliorated by having many more active participants in the competition market.) In 2009, the four largest banks supplied 67% of the market of mortgages, and, in 2006, the ‘big four’ banks accounted for 47% of the market. According to the “Cruickshank review”, the ‘big four’ banks accounted for 17% of the market. Demutualised building societies held 48%: these are, (a) Lloyds TSB, Halifax and Bank of Scotland; (b) Royal Bank of Scotland, Natwest; (c) HSBC, First Direct; (d) Abbey, Alliance and Leicester, Bradford and Bingley.

The Competition Commission believes that helping customers to easily switch products is paramount to the effective operation of competitive markets: markets do not function without customers who vote with their feet. As Dr Adam Marshall of the British Chambers of Commerce told the Commission: ‘There’s lots of products and services on the market, but the theoretical competition between those products and services is limited by the real world barriers of form filling, hassle, bureaucracy, decisions not being taken, etc…’ The regulator responsible for consumer protection regulation should have both: (a) an explicit mandate to promote effective competition in markets in the financial sector; and (b) the necessary powers to regulate the sector to achieve this, including the ability to apply specific licence conditions to banks and exercise competition and consumer protection legislation. These powers will be concurrent with the competition powers of the OFT, and will enable the regulator to both enforce competition law and make market investigation references to the Competition Commission.

The aim of consumer protection regulation is to promote the conditions under which effective competition can flourish as far as possible, and where not, the regulator will be able to take direct action. In order best to promote the interests of the consumer, the regulator will encourage financial firms to compete: on the merit of the quality and price of their products and services; and to gain a competitive advantage by investment in innovation, technology, operational efficiency, superior products, superior service, due diligence, human capital, and offering better information to customers. Ideally, the regulator would then step in whenever there is a sign of market failure. Market failures include: (a) poor quality information being disclosed to consumers when they are deciding whether to purchase products; (b) information asymmetry between the provider and the consumer; or (c) providers taking advantage of typical consumer behaviour such as the tendency evident in retail customers to select the default option offered, and reluctance to switch products because of inertia. Any sign of market failure indicates that competition is probably not effective, and the regulator should then take action to counteract the failure.

Therefore, it is hard to see how information imbalances are not at the heart of many ‘decisions’ affecting modern life, and can lead to imperfect decisions being made. Ideally, it is up to parties to make a full disclosure about things, whether this includes personal health or corporate misfeasance; if they are not so willing to give up their secrets, they possibly can be ‘nudged’ into doing so. Of course, some parties, particularly those intending to generate a healthy shareholder dividend, may not be very keen at all at spilling the beans, and that is where law and regulation come in. However, even then there can be significant imbalances in the legal process which can be obstructive in the correct solutions being arrived at. Certainly the field has progressed substantially since this Nobel Prize for Economics was first awarded over 30 years ago.