Home » Public Health (Page 2)

Health screening: corporates, the third sector, the NHS and the media “in it together”? BBC One’s “Long Live Britain”

The All Party Parliamentary Group Primary Care & Public Health published yesterday their ‘Inquiry Report into the Sustainability of the NHS “Is Bevan’s NHS under Threat?”‘. In their excellent report, they provided that “Preventative illnesses are overwhelming the NHS; illnesses caused by obesity, smoking, alcohol and lack of exercise. Diabetes, for example takes up 10% of the NHS budget, of which 90% is spent on dealing with preventable complications.”

The Faculty of Public Health response was follows:

“The need to treat lung cancer is waste – smoking cessation works and is far more cost effective at prolonging life than treatment for lung cancer. The need to treat heart disease is a waste – increasing physical activity levels, stopping smoking, improving diet are all preferable and cheaper. Treating measles is a waste – increasing vaccination uptake rates is more efficient; every case of HIV is a waste when it is easily preventable. There are barriers to smoking cessation (quality of services, access to services for vulnerable groups) as well as things that can be done to prevent people smoking in the first place (standardised tobacco packaging). There are barriers to preventing heart disease – transport systems and public open space that do not encourage incidental physical exercise; the availability of cheap high fat / salt / sugar food actively marketed to vulnerable populations (e.g. children); smoking (see above).”

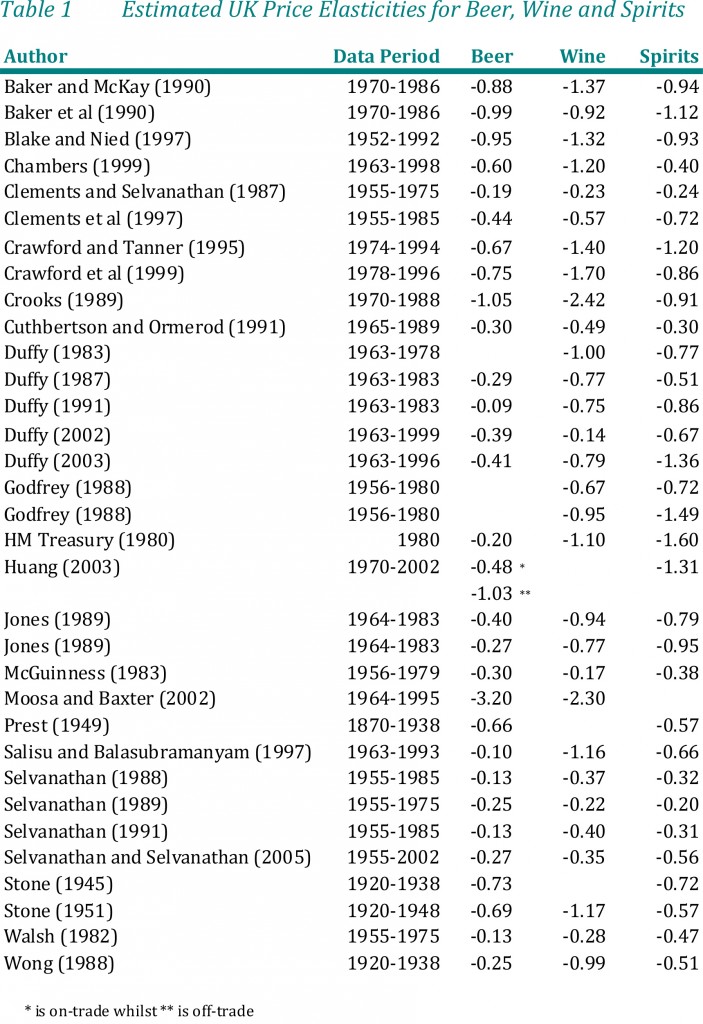

Two issues have dominated the headlines in politics and public health this week; one is the issue of standardised packaging of cigarettes and the other is minimum alcohol pricing. A new BBC One two-part series, Long Live Britain, claims to be an “one-off, record-breaking televised event that will challenge the way we tackle three of Britain’s biggest preventable diseases.” On Saturday 25 May, Long Live Britain says it “will attempt to host Britain’s biggest-ever health screening, potentially testing thousands of possible undiagnosed sufferers for the three secret killers that collectively kill 200,000 each year and affect an estimated 11 million people each year – Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and liver disease. Presented by Julia Bradbury, Phil Tufnell and Dr Phil Hammond (@drphilhammond), it is claimed that, “the fascinating results will be screened on BBC One over one night in early summer.”

However, this is a delicate issue in reality. A group of practising Doctors have set up a website, Dr Pete Deveson (GP in Epsom, Surrey) (@PeteDeveson) , Dr Margaret McCartney (GP in Glasgow) (@mgtmccartney), Dr David Nicholl (Consultant Neurologist in Birmingham) (@djnicholl), Dr Jonathon Tomlinson (GP in Hackney, London) (@mellojonny), and and Professor Charles Warlow (Emeritus Professor of Medical Neurology University of Edinburgh) because they are concerned that the promotion of private screening tests in the UK is potentially unfair to people reading many of their adverts. They indeed have complained to the Advertising Standards Authority and the General Medical Council. Some changes have been made to the adverts after their complaints (see here and here. Clearly adequate choice can only be made on complete and accurae information.

Screening is a complicated issue. Prostate cancer is a good example. If a man is showing none of the symptoms associated with Prostate Cancer why should he consider having a screening? GP Dr Pete Deveson and Dr Tony Rudd, who is a consultant stroke physician, have both publicly voiced their concerns over private health checks. Margaret McCartney (above) was written passionately on this issue in the Guardian:

“The NHS offers many screening programmes, from the heelprick test for newborn babies to breast screening for women over 50. But screening – testing well people as opposed to people who already feel unwell or who have symptoms, like a lump, or palpitations – always has the potential to harm, and is a constant balance of pros and cons. There is a risk of false positives, false negatives and false reassurance, and the problem of sometimes giving people a diagnosis they don’t need, or subjecting them to treatment they won’t benefit from. Noninvasive tests may cause few hazards, but the way the knowledge from a positive or negative scan is used may result in harm to the patient for no benefit.

We’ve seen this in prostate cancer screening: initial enthusiasm for PSA (prostate-specific antigen) screening was followed by the realisation that around a third of men operated on would suffer impotence as a result and a fifth would have incontinence.

These might be acceptable risks if the treatment was death-delaying, butmost prostate cancers don’t kill and the evidence suggests that PSA screening does not reduce death rates.

This led Richard Albin, who discovered PSA, to tell the New York Timesthat screening for it had been a “public health disaster” in the US.

So screening is often counterintuitive and harmful. Because of these inherent problems, people need to make good choices about whether to be screened based on evidence. We know, for example, that when men are given better information about PSA screening, fewer want it.”

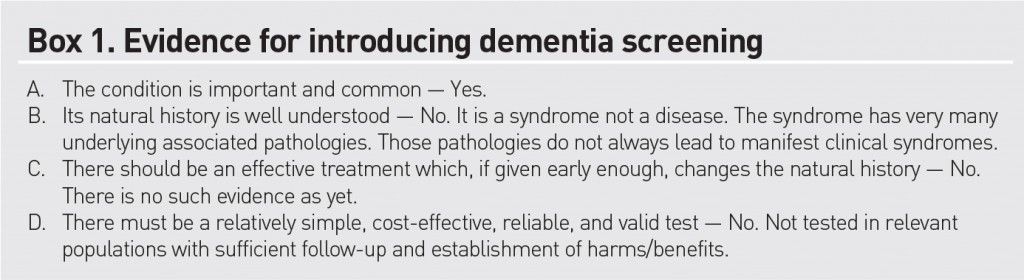

Screening has not been advocated for dementia, but this is ripe for corporate profiteering (and third sector colleagues who wish to be part of this agenda.) In an outstanding article published in British Journal of General Practice, Prof Carol Brayne and colleagues tackle this issue head on. Carol Brayne identifies the possible efficacy of ‘awareness’ campaigns in ‘generating fear’, and elaborates on these concerns:

“Turning to the private sector. It is quite possible that considerable ‘market’ can be generated through capitalisation of fear of dementia and cognitive decline. Direct-to-consumer advertising already exists for cancer (specific insurance schemes) and stroke (carotid and risk screening). Taking the example of stroke risk ‘screening’, individuals may receive, through population listings, materials that promote testing in centres sometimes hosted by primary care settings, which gives an apparent endorsement that this is evidenced practice. Could this happen with cognition? It seems likely, including the online potential. Does this matter? It depends on the outcome of the testing. If positive in some way where will these individuals turn for support? How much investigation will reassure them? How many people will be tested unnecessarily and for those who are identified as having a problem will there be sufficient resources to support them? In a publicly-funded system this will fall to their GP, who will therefore have less time for those who attend with existing concerns. In a private model these individuals may seek help elsewhere, paying for imaging and further tests. These may or may not provide reassurance or further indication of problems, but doing such tests is not, at present, justified on the basis of evidence. For some a remediable condition may be found, but as with general health screening, it will be impossible to say who has been harmed and who helped by such efforts.”

Brayne and colleagues do not feel that dementia fits the traditional Wilson-Jungner criteria for screening:

Either way, it is beginning to become clear, pursuant to an Act of parliament which enabled the outsourcing and award of contracts to the private sector in the National Health Service, and where the income in the NHS can come from private sources in up to 50%, screening is yet another issue which can be gamed by the private sector. How much the media wishes to have a genuine debate about raising awareness of clinical issues, as indeed is the agenda of the Faculty of Public Health, or gets embroiled in complex rent seeking behaviour for profitability or surplus generation of corporates and the third sector is a different matter. Of course, corporates, charities and the media, like the National Health Service, can have the best of intentions too.

Many decisions are subconscious. That’s what marketing people manipulate to make loadsamoney.

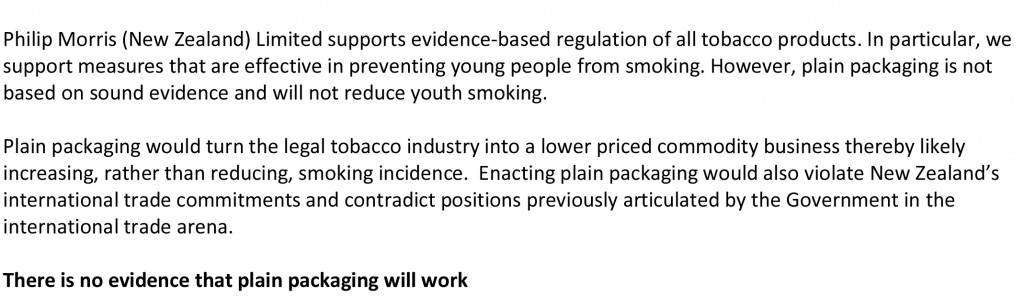

It is actually very hard to tell whether this Government’s actions are a result of a fundamentally libertarian ideology, or whether there is simply no ideology at all – they simply wish to allow their “corporate friends” to make lots of money (which as such is not an ideology). The screw-up over plain packaging in cigarettes can be interpreted at a number of different levels. One is how plausible transparency in the Government is: whilst the evidence concerning Lynton Crosby himself (and his company) is unconvincing, the lengths that international tobacco companies might go through in influencing public health policy are interesting. It could be argued that tobacco companies are simply not keen on regulation, but that does not stop Philip Morris initiating legal action at the drop of the hat. There are wider subtler inherent contraindications in the analysis of the power of the State and its rôle in public health too which will cause problems ultimately. A strong undercurrent has been the notion of “choice”, typified by Tim Kelsey’s approach to the use of data in decision-making of patients, or “customers of the NHS” as called by some. The idea that “regulation is bad” is of course fully consistent with a political philosophy from the Conservative Party, and while the Labour Party could rightly be accused of a somewhat authoritarian, “nanny state” tinge to its last attempt at office and power, the idea of the “public good” continues to gather much support in many jurisdictions.

The government has actually now mutualised its “Nudge” unit, but “Nudge” was the future once. The centrality of using behavioural insights to the Coalition government is such that it entered formal written agreement between the Conservative and Liberal parties, in the foreword by the two party leaders and their juniors:

“There has been the assumption that central government can only change people’s behaviour through rules and regulations. Our government will be a much smarter one, shunning the bureaucratic levers of the past and finding intelligent ways to encourage support and enable people to make better choices for themselves”.

Nudge is an interesting foray into consumer behaviour, and part of the problem in this is that human beings are often irrational (and certainly will make suboptimal decisions on the basis of dodgy data.) Consumer behaviour is ultimately determined by cognitive processes, such as perception, selective attention, and memory, which is why the approach to “big data” fails inherently to capture individual differences. This is a problem in planning public policy, but why should the field of marketing and economics be so interested in packaging if it does not matter? The actual evidence provides that product packaging is an important tool for suppliers to communicate with consumers.1 Tobacco manufacturers have effectively used cigarette pack design, colours, and descriptive terms to communicate the impression of lower tar or milder smoke while preserving taste “satisfaction”. Smokers’ beliefs about a given product are likely to be shaped in part by the descriptors, colours, and images portrayed on the pack and in related marketing materials.

In the US jurisdiction, “The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control” (Article 11) calls for a ban on misleading descriptors in an effort to address consumer misperceptions about tobacco products. New regulations contained in the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 (FSPTCA) prohibit tobacco companies from labelling cigarette packs with terms such as light, mild, or low after June 2010. However, experience from countries that have removed these descriptors suggests that cigarette marketers manage to circumvent the intended goal of the regulation by using different terms, colours, or numbers to communicate the same messages. Specifically, recent research has shown that consumers in the United Kingdom and Canada, which have removed “light” and “mild” descriptors, perceive cigarettes in packs with lighter colours as less harmful and easier to quit compared to cigarettes in packs with darker colours. Colour is a good example of non-verbal marketing signal, which has an important influence on our daily lives. The underlying emotions that colours evoke have been cultivated since birth and vary depending on age, geographic location, and gender (e.g. blue for boys, pink for girls). Colour, it affects, affects our moods and feelings, and research suggests that it has a physical effect as well, influencing the hormones that control our emotions.

Studies have shown that color:

- Increases brand recognition by up to 80%

- Improves readership as much as 40%

- Increases comprehension by 73%

- Can be up to 85% of the reason people decide to buy

Bansal-Travers, O’Connor, Fix,and Cummings (Am J Prev Med 2011;40(6):683–689) showed 193 participants array of six cigarette packages (altered to remove all descriptive terms) and asked to link package images with their corresponding descriptive terms. Participants were then asked to identify which pack in the array they would choose if they were concerned with health, tar, nicotine, image, and taste. Participants were more accurate in matching descriptors to pack images for Marlboro brand cigarettes than for unfamiliar Peter Jackson brand (sold in Australia). Smokers overwhelmingly chose the “whitest” pack if they were concerned about health, tar, and nicotine. Smokers in the U.S. associate brand descriptors with colours. Further, white packaging appeared to most influence perceptions of safety.

Tobacco studies indicate that health-related information in cigarette advertising leads consumers to underestimate the detrimental health effects of smoking and contributes to their smoking-related perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes. Paek and colleagues (Paek et al., 2010) examined the frequencies and kinds of implicit health information in cigarette advertising across five distinct smoking eras covering the years 1954-2003. Most notably, a majority of the cigarette ads portrayed models smoking, lighting, or offering a cigarette to others. Rooke and colleagues (Rooke et al., 2010) investigated how tobacco displays are used at the point of sale (PoS) as an important means for the tobacco industry to communicate with consumers. With regulations prohibiting PoS displays recently having come into force in Ireland, this is an increasingly important issue. Over 100 retailers were visited, with interviews taking place on site. Information was gathered on the type and size of tobacco display, who was paying for the display, requirements and incentives, and visits by industry representatives. The majority of retailers had gantries provided by tobacco companies. A minority of these were fitted with automated dispensers called retail vending machines. Attractive lighting and colour were often used to highlight particular products. Wakefield and colleagues (Wakefield et al., 2002) investigated the role of pack design in tobacco marketing. A search of tobacco company document sites using a list of specified search terms was undertaken during November 2000 to July 2001. Many smokers are misled by pack design into thinking that cigarettes may be “safer”. There is a need to consider regulation of cigarette packaging.

The World Health Organization applauded Australia’s law on plain packaging noting that “the legislation sets a new global standard for the control of a product that accounts for nearly 6 million deaths each year” The Cancer Council of Australia hailed the passing of the legislation, stating, “Documents obtained from the tobacco industry show how much the tobacco companies rely on pack design to attract new smokers….You only have to look at how desperate the tobacco companies are to stop plain packaging, for confirmation that pack design is seen as critical to sales.” Don Rothwell, professor of international law at the Australian National University, noted that Philip Morris was pursuing multiple legal avenues. The Notice of Arbitration under the bilateral investment treaty between Hong Kong and Australia has a 90-day cooling off period after which the case would most likely be sent to the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes in Washington. He stated that Philip Morris was most likely aiming for the Australian Government to back down, or failing that, to sue for compensation. He said the questions to decide are whether the legislation means that Australia would acquire property by the imposition of these rules and if this legislation is a legitimate public-health measure. Gavin Allen of the Daily Mail newspaper reported that the Philip Morris lawsuit could cost the Australian government “billions”. He also noted that the Australian law is being closely watched by other governments in Europe, Canada and New Zealand. In 2005, the World Health Organization urged countries to consider plain packaging, and noted that Bhutan had banned the sale of tobacco earlier in 2011.

As the latest row over the role of big money in politics hit Downing Street, Paul Burstow, who was a health minister until September last year, said Crosby should either quit or be sacked by Cameron after it emerged that his lobbying firm works for global tobacco giant Philip Morris. Other Liberal Democrats also made clear they were furious and would fight to ensure Crosby was removed from any role in which he could influence health or any other coalition policy. Amid the growing furore, the Tory chairman of the all-party select committee on health, former health secretary Stephen Dorrell, announced that his committee would look into why the government had changed its mind on the question of cigarette packaging.

This is a very serious issue. The Observer editorial was devoted to it this morning.

As the Smokefree Action Coalition points out, cigarettes are the only legal product sold in the UK that kill their consumers when used exactly as the manufacturer intends. Even if the government remains unconvinced of the wisdom of plain packaging, an alliance of MPs, charities and health experts and the Faculty of Public Health disagree, as does the public. A YouGov poll in February found that 64% of the public is also in favour. So why the sudden U-turn?

The tobacco giants are spending £2m in a campaign against standardised packaging. Critics also point out that the industry has its very own Trojan horse inside Number 10, in the shape of Australian Lynton Crosby, the Conservatives’ general election co-ordinator. Hours after the decision to postpone plain packaging, it emerged that Crosby’s company, CTF, has been advising Philip Morris Ltd in Britain since November. Now there are calls for an inquiry. As the lacklustre bill on lobbying moves through parliament, Deborah Arnott, chief executive of the health charity Action on Smoking and Health, rightly says: “David Cameron has called political lobbying the ‘next big scandal waiting to happen’. Happen it has, right in 10 Downing Street.” Tory MP and GP Dr Sarah Wollaston, who also campaigns for price controls on alcohol, aptly tweeted: “RIP public health. A day of shame for this government; the only winners big tobacco, big alcohol and big undertakers.”

“There is another fundamental contradiction in nudging, particularly in the context of the declared intent to increase a sense of individual responsibility outlined by the Prime Minister. Whilst there may be an attempt to provide at least token interference transparency to preserve the possibility of exposing a ‘nudge too far’, this also underlines how far this process is from one that encourages greater learning about problems and how the individual might take on some responsibility for their management. Behaviouralism directs us away from building the renewed sense of personal and social responsibility the Coalition government has set out as fundamental to its mission.”

Therein lies the rub perhaps. While promoting “individual choice” through nudges, the policy has inadvertently discouraged personal responsibility, and especially responsibility for other members of the community. The critical problem is that the whole is not the sum of its constituent parts, and while FA Hayek’s “The Road to Serfdom” was hailed by Margaret Thatcher (whose remark was passionately argued by the Bishop of London at her funeral to have been misquoted), cognitive neuroscience acknowledges that individuals often make the “wrong” choices – wrong for them individually, and also wrong for society. Many decisions are unconscious, and indeed that is what the whole of the profit-generating marketing industry is devoted to manipulating. But the fact that these decisions are unconscious tells you exactly what is fundamentally incorrect about the libertarian analysis. People don’t know why they’re making certain decisions: they are not in control at all. The advertisers are. And more importantly, they cannot learn from their decision-making process. Public health, for all its possible faults, is firmly against this philosophy.

References

Paek HJ, Reid LN, Choi H, Jeong HJ. (2010) Promoting health (implicitly)? A longitudinal content analysis of implicit health information in cigarette advertising, 1954-2003. J Health Commun. 2010 Oct;15(7):769-87. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.514033.

Rooke C, Cheeseman H, Dockrell M, Millward D, Sandford A. Tobacco point-of-sale displays in England: a snapshot survey of current practices. Tob Control. 2010 Aug;19(4):279-84. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.034447. Epub 2010 May 14.

Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK, Cummings KM. (2002) The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. Mar;11 Suppl 1:I73-80.

Bansal-Travers, M, O’Connor, R, Fix, BV, Cummings, KM (2011) What Do Cigarette Pack Colors Communicate to Smokers in the U.S.? Am J Prev Med 2011;40(6):683– 689

What Labour must do to prove that the NHS is ‘safe in its hands’

The problem with the mantra, “The NHS is safe in our hands”, is that it sums up a lean-management approach to management of the NHS. Whilst heralded by some as a ‘success’ in the National Health Service as an efficient way of doing things, its reputation in the private sector is rather more notorious. It is associated with a ‘just-in-time’ approach, where things are always done at the last minute. Where there is relevant to operations management is that if anything untoward happens the system becomes quite unable to cope. Take for example a major road traffic accident, or any similar clinical incident.

Labour will ultimately wish more than the basic aspiration that “NHS is safe in its hands”. This would be like me reassuring you if you asked me to childmind your baby, “You can rest assured that I won’t kill your lovely baby tonight.” And yet possibly expectations for the NHS have become rather low. The formidable campaigner, Marcus Chown, has a tweet which you often see in circulation thus:

Take for example this tweet from 18 March 2012:

Many accept this claim to be a bare-faced lie. The idea that David Cameron and the Conservative Party are simply pathological liars about the NHS is not new. They intended a full-blown reorganisation of the #NHS prior to coming into Government, and yet stubbornly refused to put it in their 2010 manifesto. Further to this, Cameron has previously made pledges to save A&E hospitals which his Government has subsequently shut down, and yesterday did a full-frontal U-turn on minimum pricing in alcohol. In terms of currency in credibility, Cameron needs to ‘sell, sell, sell’, encapsulated in the spirit of another famous tweet by Marcus Chown:

Many accept this claim to be a bare-faced lie. The idea that David Cameron and the Conservative Party are simply pathological liars about the NHS is not new. They intended a full-blown reorganisation of the #NHS prior to coming into Government, and yet stubbornly refused to put it in their 2010 manifesto. Further to this, Cameron has previously made pledges to save A&E hospitals which his Government has subsequently shut down, and yesterday did a full-frontal U-turn on minimum pricing in alcohol. In terms of currency in credibility, Cameron needs to ‘sell, sell, sell’, encapsulated in the spirit of another famous tweet by Marcus Chown:

Again, it’s a case maybe of, “If I were starting now, I wouldn’t go from here.” But we’re now stuck with the Health and Social Care Act (2012), that is until Labour decides to repeal it. However, that as we all know is only part of the story. Removing the 50% of cap from private income (section 164(1)(2A)) and redrafting the Regulations associated with procurement such that the default option is not price competitive tendering (section 75) should be the relatively easy parts. There’s still the problem for all parties of how the NHS can be legislated for integration, as strictly speaking bundling offends EU competition law if it distorts trade.

Again, it’s a case maybe of, “If I were starting now, I wouldn’t go from here.” But we’re now stuck with the Health and Social Care Act (2012), that is until Labour decides to repeal it. However, that as we all know is only part of the story. Removing the 50% of cap from private income (section 164(1)(2A)) and redrafting the Regulations associated with procurement such that the default option is not price competitive tendering (section 75) should be the relatively easy parts. There’s still the problem for all parties of how the NHS can be legislated for integration, as strictly speaking bundling offends EU competition law if it distorts trade.

Ed Miliband has been deeply immersed in a debate about party funding and transparency. Whilst Matt Forde claimed this week on “This Week”, the flagship politics show presented by Andrew Neil, that the Unions to have a “strangehold” on the Labour Party, it is not terribly certain how robust Labour’s opposition to Royal Mail privatisation will be. It is also noteworthy that UNISON violently opposed the ‘Private Finance Initiative’, admittedly brought in through Ken Clarke and John Major in the mid 1990s, but which Labour (and the Conservatives) have subsequently embraced. The loans for PFI have benefited the private sector, and the funding of NHS Foundation Trusts via this route has led some lawyers representing these trusts to withhold vital information such as staffing levels on the grounds that such information is “commercially sensitive”.

Therefore, Labour, even if offers a ‘safe alternative’ to the funding gap and the mechanism of procurement in a future Government, does not offer anything startingly different on the Private Finance Initiative. This would not matter if this issue was completely unknown to voters, but the issue is very well known. Some members of the public know that it is known as ‘off ledger accounting’, and that City firms are still very positive about it. Andy Burnham MP has long argued that the PFI was essential for improving the infrastructure of hospitals, e.g. spanking new businesses, but this is small beer for wards and NHS services being stripped to the bone. NHS Trusts being run with a skeleton staff at full capacity, such that Doctors and nurses feel they can’t cope, are becoming commonplace. This is as being justified in terms of the ‘necessary’ £20bn of NHS savings which have to be found until 2020 at least. No party wishes to challenge these savings, and that is partly the reason they find Sir David Nicholson a useful lightning conductor. He is the natural conduction rod for public anger, and indeed the Daily Mail’s anger, whereas all that is happening is that the messenger is being shot, and another messenger will possibly take over next year, for example Mark Britnell.

Labour does not wish to challenge the idea that the NHS is being stripped of necessary funds to do the job properly. If the demands from ageing and technological advances have increased as Nicholson and others claims, surely it is unfeasible to maintain the same level of service when you are barely changing the budget in incremental terms from year to year? Labour’s failure to challenge this dogma is at the heart of its other failings. It cannot embrace the disasters at Mid Staffs and Morecambe Bay while it is fully signed up to efficiency savings. Nobody can deny that any large organisation needs to be run at maximum productivity and efficiency, but when there is consistent robust evidence that adequate numbers of Doctors and Nurses saves lives this is a problem. Labour’s new line of attack is that the “hedgies” (hedge funds) have a strangehold on Tory policy, a weapon utilised to great effect by Ed Miliband in Prime Ministers’ Questions only this Wednesday (10 July 2013). It is a poorly kept secret that private sector entities made massive donations to the Conservative Party prior to the 2010 General Election, and as a result of the new NHS legislation, this situation latterly appeared (source):

For all the ranting by the Conservatives and Labour about “choice”, ultimately voters seem to have little choice where it matters. Citizens of Trafford and Lewisham appear to have little choice over their A&Es locally shutting. Reconfigurations seem to happen from Jeremy Hunt with little consultation with the public. Labour’s public opposition to these distressing reconfigurations seems to be minimal, in a way almost to suggest a collusion with the Government agenda to “reconfigure to save money”. And the dogma of the efficiency savings from the Department of Health goes unchallenged, including the surplus returned to the Treasury, in parallel to the big ticket numbers expenditure-wise going unchallenged. How come it’s possible to find the billions of HS2, another initiative which few people remember ‘voting for’, which has a dodgy business plan, and yet is unanimously agreed upon by all parties (like PFI)? It has become unacceptable to challenge anything coming out of the private sector, whether it’s the efficiency savings advised by McKinsey’s who have been advising on re-disorganisations since time began, well certainly since 1974 anyway. Coupled with this with toothless regulators (and in the CQC’s case a regulator which is allocating resources to protect its own reputation and whose own Report it is alleged is a ‘cover up of a cover up’), it is possible that the damage done by efficiency savings will go unnoticed. If the focus remains on reputational succes of NHS Trusts, and the reputational success of politicians of all ilk, any collusion between the Regulators and politicians to achieve NHS Foundation Trust will be disastrous. Andy Burnham has vehemently denied that there has been any such pressure thus far, but the future of the NHS Foundation Trust is highly relevant. Despite it being a noteworthy policy failure in Spain, the widespread conversion of hospitals to NHS Foundation Trusts could be the perfect stepping stone for super-hospitals, and in a market where supplier power is King, they may prove yet to be the perfect vehicle for the final part of NHS privatisation.

The thing is while it is easy to hide poor financial performance of the hospital, and this is after all the metric that will pay the salaries of CEOs in NHS Foundation Trusts, it is alarmingly easy to hide morbidity and excess mortality of NHS hospitals. Nobody wants to go into hospital to put their own life at risk, and yet we have this ludicrous situation, generated by all the political parties, where nobody accepts blame, and senior managers are in a ‘revolving door’ around the system with generous rewards for, ultimately, failure. The idea of the National Health Action party being the next Government is frankly ludicrous, which is why it is all the more important that Labour can strengthen its relationship with the Unions. However, the efforts of the NHA Party in putting this crucial agenda on the map are completely worthwhile if they move forward from being simply a ‘party of protest’. Maybe despite having been born out of the Unions to represent workers in Parliament, Labour does not feel that it should offer unfair advantage to the Unions, but this would be catastrophic in policy terms. The “democratic deficit” on the NHS is extremely bad, with the general public and the medical professions completely ignored on a range of issues, most recently plain packaging of cigarettes and minimum alcohol pricing. It’s the singularly obsessional Labour phobia of the perception of its relationship with the Unions with the right-wing press which means that it too might easily go down the route of being susceptible to powerful corporate lobbying over diet, alcohol, smoking, and the such like. This stems from the basic issue of turning the NHS into a profitable business, as a “wealth creator”. It is a world apart from “The Spirit of 45″, and Labour knows that it is sitting on an extremely comfortable lead of about 10% compared to the Conservatives.

Labour has to learn not to abuse this public faith in it regarding the NHS, and take a “second look” at NOT embracing a neoliberal, un-evidence based approach to medicine. It, like the NHS, has to learn from failure. Whilst whole-person or integrated care is important, it must never become, fundamentally, distraction therapy from the threats still posed by PFI and efficiency savings. Labour has been desperate for the Risk Register to be published, but it is highly likely that the Risk Register will also expose failures from their watch in Government.

It’s not the case that Labour is ‘sleepwalking’ into a disaster. It already has sleep-walked into a disaster, and it’s high time to retreat. Soon, it will be the case, at best, that people are not wishing to vote Labour over the NHS, but they represent “the best of a bad bunch”. Yet this ironically is entirely in keeping with the “just in time” philosophy of doing the rock bottom or “more for less”. Labour appears to be suffering from a ‘poverty of aspiration’, and whilst the emphasis in policy seems to be one of ‘equality of opportunity’ for profit-making healthcare private providers, it is this poverty of aspiration that might ultimately kill the NHS.

The author can easily be contacted on Twitter @legalaware.

Does the epidemiology of dementia constitute an ‘epidemic’, and does it warrant a “moral panic”?

The whole use of language surrounding the diagnosis of dementia matters, not least in the general context of how risk is communicated with the general public. A further problem is that medical terms often get adopted by more general media such as tabloids in a fairly non-discriminatory way. Take for example. the formal definition of an “epidemic” is:

“The occurrence in a community or region of cases of an illness, specific health- related behavior, or other health-related events clearly in excess of normal expectancy.”

(Greenland, Last and Porta, 2008)

According to Prof Paradis at Stanford University (2012), presented later by Paradis and colleagues (Paradis et al., 2012) in a public presentation, there has been an apparent ‘epidemic of epidemics‘, with no apparent restriction on the type of disease, on frequency or rates of affliction; there was no growth or contagion threshold. In the forthcoming decades, it is predicted that large numbers of people will enter the ages when the incidence rates of forms of dementia are the highest. People sixty years and over make up the most rapidly expanding segment of the population: in 2000, there were over 600 million persons aged 60 years or over worldwide, comprising just over 10% of the world population, and, by 2050 it is estimated that this figure will have tripled to nearly two billion older persons, comprising 22% of the world population (United Nations, 2007). Stephan and Blossom (2008) from the University of Cambridge state specifically that, “this ageing epidemic, while once limited to developed countries, is expected to become more marked in developing countries.” Supporting this, Sosa-Ortiz, Acosta-Castillo, and Prince (2012) propose that “global population aging has been one of the defining processes of the 20th century, with profound economic, political and social consequences. It is driving the current epidemic of dementia, both in terms of its extent and global distribution.” It could be that stakeholders in the research community, as Paradis (2011) proposes, are effectively competing for “social capital” (after Bourdieu, 1986). Bourdieu’s definition of ‘capital’ extends fat beyond the notion of material assets to capital that may be social, cultural or symbolic (Bourdieu 1986: cited in Navarro 2006).

In professional circles, the diagnosis of dementia enmeshes a plethora of ethical issues, as reviewed elegantly by Strech and colleagues (Strech et al., 2013):

- Risk of making a diagnosis too early or too late because of reasons related to differences in age- or gender-related disease frequencies

- Risk of making inappropriate diagnoses related to varying definitions of mild cognitive impairment

- Underestimation of the relatives’ experiences and assessments of the person with dementia

- Adequate point of making a diagnosis:

- Risk of disavowing signs of illness and disregarding advanced planning

- Respecting psychological burdens in breaking bad news

- Underestimation of the relatives’ experiences and assessments of the person with dementia Reasonableness of treatment indications:

- Overestimation of the effects of current pharmaceutical treatment options

- Considering challenges in balancing benefits and harms (side- effects)

- Not considering information from the patient’s relatives

- Adequate appreciation of the patient:

- Insufficient consideration of the patient as a person

- Insufficient consideration of existing preferences of the patient

- Problems concerning understanding and handling of patient autonomy

A correct early diagnosis may be clarifying, and appreciated by patients even without disease-modifying treatment, and a diagnosis could be valuable since it allows informed planning for the future (Kaduszkiewicz, Bachmann, and van den Bussche, 2008). A ‘positive test result’ indicating dementia of Alzheimer type (“DAT”) will almost certainly lead to extended follow-up., and that individual being plugged into the system. However, at worst, the diagnosis could lead to stigmatisation resulting in feelings of hopelessness, agony, and despair. The rôle of the clinician and support, such as family members, relatives, friends, and other members of the “dementia-friendly community”, will be to mitigate against this risk. From a legal perspective, a test result indicating DAT could potentially affect insurance premiums (sic), and the right for an individual to hold a driver’s licence, depending on the jurisdiction in question. Certainly, the ethical consequences in falsely diagnosed cases could be grave. Furthermore, as Matthson and colleagues explore (Matthson, Brax and Zetterberg, 2008), If a false positive diagnosis results in treatment, any harmful side effect is a serious infringe on the basic medical ethics principle of non-maleficience, accurately summarised in the Latin phrase primum non nocere (“first, do not harm”).

A salutory warning is provided by the well documented discussions of the communication of obesity as a public health issue. The very fast increase in mass media attention to obesity in the U.S. and beyond seems to have many of the elements of what social scientists call a ‘moral panic’. Moral panics are typical during times of rapid social change and involve an exaggeration or fabrication of risks, the use of disaster analogies, and the projection of societal anxieties onto a stigmatized group (Cohen, 1972; Goode and Ben-Yehuda, 1994). Moral panic is a term usually used to describe media presentation of something that has happened that the public will react to in a panicky manner. Moral panic has a tendency to exaggerate statistics and to create a ‘bogey-man’, known as a ‘folk-devil’ in sociological terms. In recent years moral panic and media presentation have covered a wide-ranging number of topics from HIV/AIDS in the 1980s to immigrants into the UK in the 2000’s. Moral panic goes back as far as World War One when the wartime government used the media to portray the Germans in a certain manner in the hope of provoking a response. The conduct of the media is pivotal in all this.

Despite arguably the very weak evidence that obesity represents a health crisis, scientific studies and news articles alike continue to treat the population’s weight gain as an “impending disaster”. A content analysis of 221 press articles discussing scientific studies of obesity found that over half employed alarming metaphors such as ‘time bomb’ (Saguy and Almeling, 2005). The fundamental problem is that there is no adequate treatment for the commonest type of dementia, DAT, and yet authors still talk in a language suggesting that it is possible to treat this epidemic successfully. For example, Korczyn and Vakhapova (2007) in their article entitled, “The prevention of the dementia epidemic”, cite polio as an example of an epidemic which was successfully ‘treated’.

“The last epidemic which has been fought with outstanding success is poliomyelitis. In order to win that war, the first step was to identify the cause, the polio virus. The next step, achieved within a few years, was to develop methods to cultivate the virus. Justifiably, J. Enders, T. H. Weller and F. C. Robbins were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1954 for this important discovery, which led to the development of immunization (sic) methods by A. B. Sabin and J. E. Salk.”

This is nothing new. Even the Department of Health (2002) has referred to the “obesity time bomb“:

“The growth of overweight and obesity in the population of our country – particularly amongst children – is a major concern. It is a health time bomb with the potential to explode over the next three decades…. Unless this time bomb is defused the consequences for the population’s health, the costs to the NHS and losses to the economy will be disastrous.” (Department of Health 2002)

In a remarkable paper, Bethan Evans (2010) considered the characterisation of obesity as a ‘threat to the future nation’ through considering obesity as a biopolitical problem – which simultaneously addresses the individual body and the ‘population’ (Foucault 1997) – and as a form of “pre-emptive politics”. According to Massumi (2007), pre-emptive action is not legitimised through ‘scientific truths’ established to know the future, but through the (re)production of ‘affective facts’ which make potential futures felt in the present. This ensures ‘any action taken to pre-empt a threat from emerging into a clear and present danger is legitimated by affective fact of fear, actual facts aside’ (Massumi 2007). An example of this use of language is seen in the report of Alzheimer’s Disease International (2012) on stigma in DAT. They clearly wish the reader to project to the future.

“Our healthcare and financial systems are not prepared for this epidemic. Dementia is the main cause of dependency in older people 1, and we will not have enough people to care for these large numbers of people with dementia. Globally, less than 1 in 4 people with dementia receive a formal diagnosis Without a diagnosis, few people receive appropriate care, treatment and support.”

The authors of that particular report cite numerous examples supporting their thesis than an early diagnosis is beneficial. For example, they state that, Scotland’s national dementia plan includes ‘overcoming the fear of dementia’ as one of its plan’s five key goals. This plan seeks to improve access to diagnosis by providing general practitioners with information and resources. If the “dementia epidemic” is a real one, according to Nepal and colleagues (Nepal et al., 2008), policy strategies to deal with the dementia “epidemic” could be informed in a number of ways. The prevalence depends upon interaction of age with other factors (e.g., co-morbidities, genetic or environmental factors) that in turn are subject to change. If onset of dementia could be postponed by modulating its risk factors, this could significantly affect its incidence (e.g. review, Treves and Korczyn, 2011). The need for longitudinal and population-based data that would enable analyses of resource allocation and cost implications has been identified (Wimo and Winblad, 2004). Conducting prospective intervention studies is an established approach to test alternative policy models in the field, but these studies require substantial investment in time and resources. Computer-based dynamic microsimulation models are an ideal alternative to these, as the computer simulations provide an opportunity to test a range of policy options in a virtual world in a shorter time frame.

Nonetheless, this debate is better ‘out than in’, and should be conducted openly for the benefit of those individuals with dementia, and their most immediate people in their community, including partners, friends, relatives or family members. Even charities have been known to use terms such as ‘epidemic’ and ‘timebomb’ in common parlance, and the debate above could go some way into explaining why the word “early” in dementia diagnosis has been replaced by “timely” in most UK circles. As we are all relatively new to the dementia journey, some more than others, it is appropriate we stop to think before rushing at full speed into an uncontrollable situation about communication.

[Thank you very much to @nchadborn and @peterdlrow for useful discussions on this issue through the medium of 'Twitter'.]

References

Alzheimer’s Disease International (2012) World Alzheimer Report 2012: Overcoming the stigma of dementia, London: Alzheimer’s Disease International, available at: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2012.pdf.

Bourdieu, P. (1986) The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (New York, Greenwood), 241-258.

Cohen, Stanley. (1972) Folk Devils and Moral Panics, Routledge: New York.

Department of Health (2002) Annual report of the chief medical officer 2002: Health check, on the state of the public health, available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/PublicationsAndStatistics/Publications/AnnualReports/DH_4006432.

Evans, B. (2010) “Anticipating fatness: childhood, affect and the pre-emptive ‘war on obesity’”, Trans Inst Br Geogr, 35, pp. 21–38.

Foucault, M. (1997) “Society must be defended: lectures at the Collège de France 1975–76 Translated by Macey, D.”, London: Penguin.

Goode E, Ben-Yehuda N. Moral Panics: The Social Construction of Deviance. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1994.

Greenland, S., Last. J.M., and Porta, M.S.(2008) A dictionary of epidemiology, New York: Oxford University Press.

Kaduszkiewicz, H., Bachmann, C., and van den Bussche, H. (2008) “Telling “the truth” in dementia-Do attitude and approach of general practitioners and specialists differ?”, Patient Education and Counseling, vol. 70, no. 2, pp. 220–226.

Korczyn, A.D., and Vakhapova, V. (2007) “The prevention of the dementia epidemic”, J Neurol Sci, 15. pp. 257(1-2):2-4.

Massumi, B. (2007) The future birth of the affective fact: the political ontology of threat forthcoming, in Pollock ,G. (ed ), The ethics and politics of virtuality and indexicality, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mattsson, N., Brax, D., and Zetterberg, H. (2010) “To know or not to know: ethical issues related to early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease”, Int J Alzheimers Dis,. pii: 841941.

Navarro, Z. (2006) ‘In Search of Cultural Intepretation of Power’, IDS Bulletin 37(6): 11-22.

Nepal, B., Ranmuthugala, G., Brown, L., and Budge M. (2008) “Modelling costs of dementia in Australia: evidence, gaps, and needs”, Aust Health Rev, 32(3), pp. 479-87.

Paradis, E. (2011) Changing meanings of fat: Fat, obesity, epidemics and America’s children, Stanford University unpublished dissertation.

Paradis, E., Albert, M., Byrne, N., and Kuper, A. (2012) Changing Meaning of Epidemic and Pandemic in the Medical Literature, 1900-2010. American Sociological Association Conference, Denver, CO: August, available at: http://www.eliseparadis.com/files/EoE-DenverV1.pdf.

Saguy, A.C., and Almeling, R. (2005) ‘Fat devils and moral panics: news reporting on obesity science.’ Presented at the SOMAH workshop. UCLA Department of Sociology. June 1.

Sosa-Ortiz, A.L., Acosta-Castillo, I., and Prince, M.J. (2012) “Epidemiology of dementias and Alzheimer’s disease”, Arch Med Res., 43(8), pp. 600-8.

Stephan, B., and Brayne, C. (2008) Prevalence and projections of dementia, in: Excellence in Dementia Care: Principles and Practice (eds. Downs, M. and Bowers, B), Maidenhead (UK): Open University Press (McGraw-Hill Education).

Strech, D., Mertz, M., Knüppel, H., Neitzke, G., and Schmidhuber, M. (2013) “The full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia care: systematic qualitative review”, Br J Psychiatry, 202, pp. 400-6

Treves, T.A., and Korczyn, A.D. (2012) “Modeling the dementia epidemic”, CNS Neurosci Ther., 18(2):175-81.

Wimo, A., and Winblad, B. (2004) “Economic aspects on drug therapy of dementia”, Curr Pharm Des, 10, pp. 295-301.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2007) World Population Ageing 2000. Repository at: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/publications.htm.

Foreword to my book ‘Living well with dementia’ by Prof John Hodges

This is the Foreword to my book entitled ‘Living well with dementia‘, a 18-chapter book looking at the concept of living well in dementia, and practical ways in which it might be achieved. Whilst the book is written by me (Shibley), I am honoured that the Foreword is written by Prof John Hodges.

Prof Hodges’ biography is as follows:

John Hodges trained in medicine and psychiatry in London, Southampton and Oxford before gravitating to neurology and becoming enamoured by neuropsychology. In 1990, he was appointed a University Lecturer in Cambridge and in 1997 became MRC Professor of Behaviour Neurology. A sabbatical in Sydney in 2002 with Glenda Halliday rekindled a love of sea, sun and surf which culminated in a move here in 2007. He has written over 400 papers on aspects of neuropsychology (especially memory and languages) and dementia, plus six books. He is building a multidisciplinary research group focusing on aspects of frontotemporal dementia.

I would like to propose a SHA committee on the use of GP data in the NHS

The GP-patient consultation is a pivotal part of everyday activity of the NHS. Whilst the reasons that a patient may decide to go to see his or her GP are diverse, it is clear that much information is exchanged in that consultation. Some of that information will be relevant for deciding upon the need for further investigations and examination, and even possible referral to other parts of the NHS. The data might therefore very useful at an individual level. However, the data, taken as a whole for a population, might also produce useful insights which are relevant for further research, and are therefore enormously beneficial for public health.

The GP-patient consultation is a pivotal part of everyday activity of the NHS. Whilst the reasons that a patient may decide to go to see his or her GP are diverse, it is clear that much information is exchanged in that consultation. Some of that information will be relevant for deciding upon the need for further investigations and examination, and even possible referral to other parts of the NHS. The data might therefore very useful at an individual level. However, the data, taken as a whole for a population, might also produce useful insights which are relevant for further research, and are therefore enormously beneficial for public health.

When a patient goes to see his/her own GP, normally the patient has an expectation that the consultation will be confidential. This is at the crux of the doctor-patient relationship.

1. Medical confidential data from an individual perspective

From April 1st 2013 there was a noteworthy change to the way in which the Department of Health collected information about patient health from GP record systems in England. Previously, mainly aggregate health data was collected and patients could sometimes opt out of having identifiable information from their own record uploaded to central systems. From April 1st, the newly-renamed NHS “Health and Social Care Information Centre” (HSCIC) began uploading identifiable patient information, without telling patients how they can opt out of this process – or even that they can. The data uploaded included every patient’s NHS number, date of birth, postcode and ethnicity, together with details of medical conditions, diagnoses and treatments.

That information is held on HSCIC and other NHS systems where it will be used to analyse health trends and demand for services, improve treatment and provide evidence upon which local clinical commissioning groups can base decisions about service provision. The data will also be made available to outside parties such as researchers and for-profit companies, and this is where the concern that “data will be sold to the highest bidder” has emerged from in the recent media (see for example the Guardian, “£140 buys private firms data on NHS patients”, article by Randeep Ramesh @tianran 17 May 2013). The HSCIC say that it will be ‘anonymised’ before release, but the concept of anonymisation is highly controversial and it is unlikely that guarantees can be given about the possible re-identification of the data.

2. Medical confidential data from a population perspective

However, there is also a parallel consideration, which could be seen as a fundamental socialist goal of solidarity. Patient records in general practice surgeries constitute a unique resource that can provide evidence to help medical researchers improve their understanding of disease, develop potential new treatments and improve patient care. But patient information is both sensitive and private, and the security of personal data must be safeguarded. The Wellcome Trust in 2009 argued that Research has shown that the public are generally supportive of research. Two-thirds of people are likely or certain to allow ‘personal health information’ to be allowed for research – however, there is little public understanding of what this actually means in practice.

As such, the Wellcome Trust therefore believed it was imperative to improve engagement and awareness among the general public:

- there should be a national awareness-raising programme highlighting the importance of using patient records for research, describing the difference between identifiable and non-identifiable data, and explaining the safeguards that will be put in place to protect privacy

- information should also be provided locally through general practices, for example as patients register at a practice, and through posters and leaflets.

The Wellcome Trust argued that, “transparency is essential, and it should be clear that patients can opt out of the use of their identifiable information in research if they wish.” For example, there may be times when it might be useful to know how agents of the NHS themselves behave in making decisions, for example to what extent GPs comply with NICE guidance, and to look for any reasonable deviation from ‘best practice’.

There is a plethora of approaches which could be taken to a ‘train of enquiry’ in how information has handled at GP level. The aim of this Committee is not to go on a ‘fishing expedition’ about all the uses of information at a GP level, for example incentives in making clinical decisions or ‘Nudge’.

The aim of this proposed Committee, for which applications from any interested parties are invited, including from General Practice, academics, doctors in other specialties (especially public health), and patients themselves, is to consider primarily whether patients in the NHS are aware of their ‘rights’ about the information they provide into the NHS, and how the needs for patient confidentiality at an individual and population level can be reconciled from the perspectives of the patient, the researcher, and other interested parties.

Members of the Committee ideally would therefore have to keep themselves familiar with recent policy developments which are relevant, including NHS information governance (including NHS England) and the views of the research councils (including the Wellcome Trust), as well as be aware of the approximate direction of travel of the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) and EU Data Protection Regulation. It would also be useful if members of the Committee are aware of the current activities of campaigning groups such as Medical Confidential or Liberty, who have tried to raise awareness of this issue previously, and continue to work for the pursuit of that goal.

Thanking you in anticipation.

Useful background reading

http://medconfidential.org/briefings/

http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/About-us/policy/Spotlight-issues/personal-information/gp-records/index.htm

£140 buys private firms data on NHS patients: http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2013/may/17/private-firms-data-hospital-patients (Randeep Ramesh, 17 May 2013, Guardian – @tianran)

GP patient data boosts research: http://www.gponline.com/News/article/1014146/GP-patient-data-boost-research/

If I could predict the future of my health, would I change my behaviour?

A major issue in economics certainly is how individuals cope with information. Much information is uncertain, so one’s ability to make rational decisions based on irrational information is a fascinating one. Predicting the future may be viewed as best kept as the bastion of astrologers such as Mystic Meg, but the likelihood of future outcomes is clearly of interest in the insurance industry. These decisions are not only helpful for people at an individual basis, but also hopefully useful for planning, rather than predicting, what is best for the population at large in future.

Angelina Jolie did not have cancer, but, in fact, like many women with breast cancer mutations, she had the radical surgery to lower her risk. She, at the age of 37, has described her decision as “My Medical Choice,” in an op-ed in the New York Times. She carries the BRCA1 gene mutation, which gives her an 87% risk of developing breast cancer at some point in her life. The abnormal gene also increases her risk of getting ovarian cancer, a typically aggressive disease, by 50%. To counteract those odds, Jolie wrote that she decided to have both her breasts removed. In 2010, Australian scientists found that women with the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who chose to have preventive mastectomies did not develop breast cancer over the three-year follow-up. Since the genetic abnormalities increase the risk of ovarian cancer, women who had their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed also dramatically lowered their risk of developing ovarian or breast cancers. The ability of medicine to predict one day, with relative certainty, the likelihood to develop certain conditions is an intriguing way, and leaves the open the possibility of ‘personalised medicine’ on the basis of your own individual information. If you think the NHS is already overstretched, with A&E closures contributing to the ‘crisis’ in emergency health provision, then footing a bill for personalised medicine might be the ‘straw that breaks the camel’s back’. The idea that one day you can predict the likelihood of a person developing multiple sclerosis or Alzheimer’s Disease still intrigues neurologists.

This furthermore presents formidable challenges for the law. In recent years, governments have been embracing policies that ‘nudge’ citizens into making decisions that are better for their own health and welfare, including our own Government which has decided to ‘mutualise’ its own ‘Nudge Unit’. The European Commission has embraced this ‘libertarian paternalism’ in its review of the Tobacco Products Directive. Various people has recently explained that by introducing measures such as plain packaging and display bans, the European Union may be able to ‘nudge’ people into smoking less, whilst preserving their right to choose. After having relied on the assumption that governments can only change people’s behaviour through rules and regulations, policy makers seem ready to design polices that better reflect how people really behave. Inspired by “libertarian paternalism,” the nudge approach suggests that the goal of public policy should be to steer citizens towards making positive decisions as individuals and for society while preserving individual choice.

It’s likely that a ‘one glove fits all’ policy is not going to work. About a decade ago, I was surrounded in my day job by individuals with hepatic cirrhosis, requiring abdominal paracentesis to tap away fluid from their tummies. And yet being confronted with people yellow due to the build-up of bilirubin did not deter me one jot from being a card-carrying alcohol. I am not over seventy months in recovery from alcohol misuse, so this aspect of how people make decisions before being addicted intrigues me. I think that people genuinely in addiction ‘can’t say stop’, as they don’t have an off-switch; they lack insight, and are in denial, mostly, I feel from personal experience.

It’s also clear that there is a long-list of medical problems that cause someone to present to an A&E department aside from alcohol, such as a sore-throat, faint, dislocated shoulder, and so on. But alcohol is undeniably a big issue, so the question is a sobering one, pardon the pun. To what extent can we ‘nudge’ people out of alcohol-related illness? Commenting on the report out today from the College of Emergency Medicine, that highlights the pressures that Accident and Emergency (A&E) wards are under, Dr John Middleton, Vice President for Policy at the Faculty of Public Health, said:

“We quite rightly have high expectations of doctors and nurses working in emergency medicine, so it’s only fair that they get the support they need to do their jobs safely and well. One way to reduce the burden on Accident and Emergency (A&E) wards would be to tackle the reasons why people are admitted in the first place: in particular, alcohol. Given that drink related violence accounts for over one million A&E visits every year, we urgently need the government to be bold and introduce a minimum price per unit of alcohol. That would reduce the burden on overstretched hospitals and society as a whole.”

Nobody likes assessing risk, especially the consequences of an addict picking up/using again are potentially catastrophic even if in probability terms theoretically infinitesimally low. People who know about Taleb’s “Black Swan” work will know this well. And assessing harm has led others to be blasted in the public arena previously, for example Prof David Nutt who once compared the dangers of horse riding to the dangers presented by the major drugs of abuse. At a time when both the medical and legal professions at least think there should be an open debate about having ‘another look’ at the Misuse of Drugs Act (1971), hopefully a public can welcome a mature debate on this.

Even today, the news reports that introducing a law to force cyclists to wear helmets may not reduce the number of hospital admissions for cycling-related head injuries.Researchers said that while helmets reduce head injuries and should be encouraged, the decrease in hospital admissions in Canada, where the law is in place in some regions, seems to have been “minimal”. The authors examined data concerning all 66,000 cycling-related injuries in Canada between 1994 and 2008 – 30% of which were head injuries. Writing in the British Medical Journal, the authors noted a substantial fall in the rate of hospital admissions among young people, particularly in regions where helmet legislation was in place, but they said that the fall was not found to be statistically significant.

I suppose all political parties desire people with capacity to make decisions about their own lifestyle and healthcare, very much in keeping with the ‘no decision about me without me’ philosophy currently in vogue. If push came to shove, if I could predict the future of my health, would I fundamentally change my behaviour? Probably within reason, but the only thing which I am pretty certain about is having another alcoholic drink may lead to a pattern of behaviour that will ultimately kill me.

Resilience in the midst of austerity: a challenge for dementia wellbeing

In Prof. Felicia Huppert’s latest chapter entitled, “The state of well-being science: concepts, measures, interventions and policie”s, to appear in Interventions and Policies to Enhance Well-being (Huppert, F.A. and Cooper, C.L. (eds.) ), Prof. Huppert re-establishes the perspective that it is possible to demonstrate wellbeing even in the presence of a label of a clinical diagnosis. This aligns itself nicely with the argument which I have been advancing, that it is the possible to enhance the wellbeing of an individual with dementia through careful consideration of his or environment. For example, one could attempt to make the home or ward better designed, attempt to involve the individual with leisure activities or general activities (such as reminiscence therapy), seek to encourage adoption of assistive technologies or assisted-living technologies, or try to encourage more social activities including participation in a wider community. However, Huppert and So (2013), to establish what components comprise well-being, have examined carefully the internationally agreed criteria for the common mental disorders (as defined in DSM-IV and ICD-10) and for each symptom, listed the opposite characteristic. This resulted in a list of ten features which represent positive mental health or ‘flourishing’. These are: competence, emotional stability, engagement, meaning, optimism, positive emotion, positive relationships, resilience, self esteem, vitality.

Just as symptoms of mental illness are combined in specific ways to provide an operational definition of each of the common mental disorders, they proposed that positive features could be combined in a specific way to provide an operational definition of flourishing. The diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder do not require that all the symptoms be present; likewise, the operational definitions of flourishing (Keyes, 2002) do not require that all the features of positive feeling and functioning be present. There is currently a relative paucity of literature on the efficacy of psychological techniques such as “mindfulness” in enhancing wellbeing in individuals with dementia, but it is possible that innovative ways of improving any aspects of the multi-dimensional construct could be developed through such a technique. Among the reported benefits of mindfulness training in other populations, which are related to subjective well-being, are: reductions in stress and anxiety, increased positive mood, improved sleep quality, better emotion regulations, greater bodily awareness and increased vitality, and greater empathy (Huppert, in press.)

Clearly, ignoring the economic climate of an individual with dementia is not going to be possible, although I have thus far successfully managed to avoid such a discussion. The data reported in Huppert and So (2013) are from 2006/07, two years before the severe economic recession from which many countries have since suffered. Huppert (2013) argues that it would be very interesting to know if the recession has changed the prevalence of flourishing or its component features within and between countries, and the extent to which country rankings of the prevalence of flourishing may have altered. Relatively recent data from the Gallup World Poll show almost no impact of the economics crisis on subjective well-being in the UK (Crabtree, 2010). However, one clearly has to acknowledge the ‘social determinants of health”, famously described by Marmot (2012) as: “Mental health and mental illness are profoundly affected by the social determinants of health; psychosocial processes are important pathways by which the social environment … impact [s] on … physical and mental health … ” Indeed McKee and colleagues (McKee et al., 2012) make a constructive but profoundly depressing link between illbeing and austerity:

“For many months, the political and financial aspects of the crisis have filled the headlines. However, behind those headlines, there are many individual human stories that remain untold. They include people with chronic diseases unable to access lifesustaining medicines, persons with rare diseases who are losing income support and forced to care for themselves, and those whose hopes of a better life in the future have been dashed see no alternative but to commit suicide. So far, the discussion has been limited to finance ministers and their counterparts in the international financial institutions. Health ministers have failed to get a seat at the table. As a consequence, the impact on the health and wellbeing of ordinary people was barely considered until they made their feelings clear at the ballot box.”

More optimistically, Huppert and So (2011) argue that this parcellation of the positive wellbeing multidimensional construct may be useful for developing targeted interventions:

“If a population group is high on some features of well-being such as positive relationships, but low on others such as engagement or resilience, it is clear where interventions should be targeted.”

Psychosocial resilience is a dimension of wellbeing which perhaps will be worth considering in detail, of how an individual and immediates might be able to cope and adapt to future adversity. This indeed is reflected in a definition of psychosocial resilience as provided by Williams and Kemp (in press) as “a person’s capacity for adapting psychologically, emotionally and physically reasonably well and without lasting detriment to self, relationships or personal development in the face of adversity, threat or challenge.” Reaching a logical conclusion, whilst there might be aspects of life which encourage illbeing, a reasonable strategy might be to strengthen components which can help to improve specific aspects of wellbeing. This would not have been possible had it not been for the work of Prof. Felicia Huppert and colleagues emphasising that wellbeing is a multidimensional construct, in the same way that it is widely acknowledged that it is unhelpful to think of dementia as a unitary diagnosis.

The Department of Health (2012) policy document, “No health without mental health: implementation framework” very nicely produces a backdrop for emphasising the importance of wellbeing in dementia. Their core principles are set out “a clear and compelling vision, centred around six objectives: more people will have good mental health, more people with mental health problems will recover, more people with mental health problems will have good physical health, more people will have a positive experience of care and support, fewer people will suffer avoidable harm, and fewer people will experience stigma and discrimination“.

Notwithstanding this, it appears that the analysis of ‘living well in dementia’ is now benefiting from an approach which has led to an appreciation that no dementia is clinically the same; nobody’s wellbeing is exactly the same, because of the way in which all the contributing parts have come together. This approach is elegant, holds incredible promise for the future.

References

Crabtree, S. (2010) Britons’ wellbeing stable through economic crisis Gallup, November 24, 2010. Available at: http://www.gallup.com/poll/144938/Britons-W%20ellbeing-Stable-Economic-Crisis.aspx

Department of Health (2012) No health without mental health: implementation framework, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/156084/No-Health-Without-Mental-Health-Implementation-Framework-Report-accessible-version.pdf.pdf

Huppert, F. (in press) The state of well-being science: concepts, measures, interventions and policies, to appear in Huppert, F.A. and Cooper, C.L. (eds.) Interventions and Policies to Enhance Well-being, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Huppert, F.A. and So, T.T.C. (2013) Flourishing across Europe: application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being, Social Indicators Research, 110(3), pp 837-861.

Keyes, C. L. M., (2002) The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207– 222.

Marmot M. (2012) Health inequalities and mental life, Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 18, pp. 320-322.

McKee, M., Karanikolos, M., Belcher, P., and Stuckler, D. (2012) Austerity: a failed experiment on the people of Europe. Clin Med, 12(4), pp. 346-50, available at: http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/clinmed-124-p346-350-mckee.pdf.

Williams, R, and Kemp, V. (in press.) Psychosocial resilience, psychosocial care and forensic mental healthcare. In: Bailey S, Tarbuck P. (eds.) Adolescence Forensic Psychiatry, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.