The All Party Parliamentary Group Primary Care & Public Health published yesterday their ‘Inquiry Report into the Sustainability of the NHS “Is Bevan’s NHS under Threat?”‘. In their excellent report, they provided that “Preventative illnesses are overwhelming the NHS; illnesses caused by obesity, smoking, alcohol and lack of exercise. Diabetes, for example takes up 10% of the NHS budget, of which 90% is spent on dealing with preventable complications.”

The Faculty of Public Health response was follows:

“The need to treat lung cancer is waste – smoking cessation works and is far more cost effective at prolonging life than treatment for lung cancer. The need to treat heart disease is a waste – increasing physical activity levels, stopping smoking, improving diet are all preferable and cheaper. Treating measles is a waste – increasing vaccination uptake rates is more efficient; every case of HIV is a waste when it is easily preventable. There are barriers to smoking cessation (quality of services, access to services for vulnerable groups) as well as things that can be done to prevent people smoking in the first place (standardised tobacco packaging). There are barriers to preventing heart disease – transport systems and public open space that do not encourage incidental physical exercise; the availability of cheap high fat / salt / sugar food actively marketed to vulnerable populations (e.g. children); smoking (see above).”

Two issues have dominated the headlines in politics and public health this week; one is the issue of standardised packaging of cigarettes and the other is minimum alcohol pricing. A new BBC One two-part series, Long Live Britain, claims to be an “one-off, record-breaking televised event that will challenge the way we tackle three of Britain’s biggest preventable diseases.” On Saturday 25 May, Long Live Britain says it “will attempt to host Britain’s biggest-ever health screening, potentially testing thousands of possible undiagnosed sufferers for the three secret killers that collectively kill 200,000 each year and affect an estimated 11 million people each year – Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and liver disease. Presented by Julia Bradbury, Phil Tufnell and Dr Phil Hammond (@drphilhammond), it is claimed that, “the fascinating results will be screened on BBC One over one night in early summer.”

However, this is a delicate issue in reality. A group of practising Doctors have set up a website, Dr Pete Deveson (GP in Epsom, Surrey) (@PeteDeveson) , Dr Margaret McCartney (GP in Glasgow) (@mgtmccartney), Dr David Nicholl (Consultant Neurologist in Birmingham) (@djnicholl), Dr Jonathon Tomlinson (GP in Hackney, London) (@mellojonny), and and Professor Charles Warlow (Emeritus Professor of Medical Neurology University of Edinburgh) because they are concerned that the promotion of private screening tests in the UK is potentially unfair to people reading many of their adverts. They indeed have complained to the Advertising Standards Authority and the General Medical Council. Some changes have been made to the adverts after their complaints (see here and here. Clearly adequate choice can only be made on complete and accurae information.

Screening is a complicated issue. Prostate cancer is a good example. If a man is showing none of the symptoms associated with Prostate Cancer why should he consider having a screening? GP Dr Pete Deveson and Dr Tony Rudd, who is a consultant stroke physician, have both publicly voiced their concerns over private health checks. Margaret McCartney (above) was written passionately on this issue in the Guardian:

“The NHS offers many screening programmes, from the heelprick test for newborn babies to breast screening for women over 50. But screening – testing well people as opposed to people who already feel unwell or who have symptoms, like a lump, or palpitations – always has the potential to harm, and is a constant balance of pros and cons. There is a risk of false positives, false negatives and false reassurance, and the problem of sometimes giving people a diagnosis they don’t need, or subjecting them to treatment they won’t benefit from. Noninvasive tests may cause few hazards, but the way the knowledge from a positive or negative scan is used may result in harm to the patient for no benefit.

We’ve seen this in prostate cancer screening: initial enthusiasm for PSA (prostate-specific antigen) screening was followed by the realisation that around a third of men operated on would suffer impotence as a result and a fifth would have incontinence.

These might be acceptable risks if the treatment was death-delaying, butmost prostate cancers don’t kill and the evidence suggests that PSA screening does not reduce death rates.

This led Richard Albin, who discovered PSA, to tell the New York Timesthat screening for it had been a “public health disaster” in the US.

So screening is often counterintuitive and harmful. Because of these inherent problems, people need to make good choices about whether to be screened based on evidence. We know, for example, that when men are given better information about PSA screening, fewer want it.”

Screening has not been advocated for dementia, but this is ripe for corporate profiteering (and third sector colleagues who wish to be part of this agenda.) In an outstanding article published in British Journal of General Practice, Prof Carol Brayne and colleagues tackle this issue head on. Carol Brayne identifies the possible efficacy of ‘awareness’ campaigns in ‘generating fear’, and elaborates on these concerns:

“Turning to the private sector. It is quite possible that considerable ‘market’ can be generated through capitalisation of fear of dementia and cognitive decline. Direct-to-consumer advertising already exists for cancer (specific insurance schemes) and stroke (carotid and risk screening). Taking the example of stroke risk ‘screening’, individuals may receive, through population listings, materials that promote testing in centres sometimes hosted by primary care settings, which gives an apparent endorsement that this is evidenced practice. Could this happen with cognition? It seems likely, including the online potential. Does this matter? It depends on the outcome of the testing. If positive in some way where will these individuals turn for support? How much investigation will reassure them? How many people will be tested unnecessarily and for those who are identified as having a problem will there be sufficient resources to support them? In a publicly-funded system this will fall to their GP, who will therefore have less time for those who attend with existing concerns. In a private model these individuals may seek help elsewhere, paying for imaging and further tests. These may or may not provide reassurance or further indication of problems, but doing such tests is not, at present, justified on the basis of evidence. For some a remediable condition may be found, but as with general health screening, it will be impossible to say who has been harmed and who helped by such efforts.”

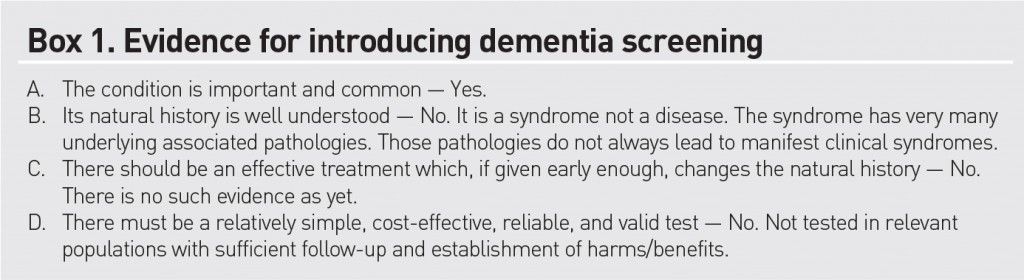

Brayne and colleagues do not feel that dementia fits the traditional Wilson-Jungner criteria for screening:

Either way, it is beginning to become clear, pursuant to an Act of parliament which enabled the outsourcing and award of contracts to the private sector in the National Health Service, and where the income in the NHS can come from private sources in up to 50%, screening is yet another issue which can be gamed by the private sector. How much the media wishes to have a genuine debate about raising awareness of clinical issues, as indeed is the agenda of the Faculty of Public Health, or gets embroiled in complex rent seeking behaviour for profitability or surplus generation of corporates and the third sector is a different matter. Of course, corporates, charities and the media, like the National Health Service, can have the best of intentions too.