Home » Posts tagged 'whole person care' (Page 3)

Tag Archives: whole person care

Are integrated care packages like M&Ms? Expect a competition law armageddon.

Somewhere along the path of the subconscious of this current Government they realised competition law, as the trojan horse for implementing the private market of the NHS, would be the ‘nuclear option’ gone too far.

After the original set of section 75 NHS regulations had been humiliatingly scrapped, Norman Lamb and other LibDem members in the Upper and Lower House had to ferret around for another way to sell this discredited policy. They found ‘integration’.

The idea of co-ordinated care bundles, delivering outcomes across a range of different domains, seems like an attractive one. For the privateers, their uncanny similarity to the Kaiser Permanente Integrated Care Plan is of course enticing.

Thrust on this that private providers can cobble together au “uber contract”, subcontracting bits of it to various bods, through the ‘prime contractor model’ – and job done.

However, this way of integrating services is a ‘red rag’ to the bull of the competition authorities both here and across the pond.

You have to have been living on the Planet Mars to escape the screw-ups of the regulation of the energy market in the UK.

In 2008, the Telegraph reported the following:

Regulator tells Treasury it has found no evidence that energy companies colluded to increase bills…

Energy watchdog Ofgem has dismissed suggestions that the UK’s six largest energy companies colluded to increase gas and electricity bills. The regulator has also demanded that those alleging price-fixing should produce the evidence.

Alistair Darling, the Chancellor, summoned Ofgem chairman Sir John Mogg and chief executive Alistair Buchanan after Npower, owned by the German giant RWE, last week increased gas prices by 17pc and electricity prices by 13pc.

Mr Buchanan said yesterday: “We have no evidence of anti-competitive behaviour. We see companies gaining and losing significant market share, record switching levels and innovative deals.”

That was unbelievably five years ago.

It was once famously said that, “Integration…is like M&Ms…a thin, sugary veneer of medical ‘science’ over a yummy core of price fixing…” (US Healthcare Executive).

In the US, health care providers are generally converge upon the view that competition concerns – namely the fear of violating competition law – have had a significant chilling effect on progress toward increased integration in the delivery of health care. This, it is claimed, has led to relative ‘conservatism’ over formal partnerships.

What happens in the UK depends on how ‘light touch’ Monitor ends to be – or whether it will be relatively supine. It is still claimed by some that the light touch regulation of the City, originally introduced by the Margaret Thatcher Conservative government, led to the City spiralling out of control.

Cartels are when companies act together to behave in a way together at the expense of the customer.

Quite irrespective of their clandestine character, cartels are difficult to prove due to their varying characteristics. Cartels can be evidentially complex in the sense that the duration and intensity of participation and the subsequent anti-competitive conduct on the market may vary and take different forms.

These specificities impose a near unbearable threshold for competition authorities to prove in detail an infringement, let aside to impose an appropriate sanction reflecting the cartelists’ real participation.

Montesquieu, in his seminal work ‘De l’esprit des lois’ observed that ‘natural equity demands that the degree of proof should be proportionable to the greatness of the accusation’. While the ‘greatness of the accusation’ in cartel infringements is undisputed – especially in light of the magnitude the incurred sanctions – it appears less clear to what extent this should affect the ‘degree of proof’ of those infringements, especially having regard to their specificities.

Article 101(1) TFEU sets out the European competition law position:

The following shall be prohibited as incompatible with the internal market all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market, and in particular those which:

(a) directly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditions;

(b) limit or control production, markets, technical development, or investment;

(c) share markets or sources of supply;

(d) apply dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage;

(e) make the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts.

In a famous case called Bayer v Commission, the Court of the First Instance, for the first time ventured to define the term ‘agreement’ as a concept that ‘centres around the existence of a concurrence of wills between at least two parties, the form in which it is manifested being unimportant so long as it constitutes the faithful expression of the parties’ intention’.

Over two centuries ago, Adam Smith, the dean of free market economics, warned: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but tbe conversa- tion ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivanee to raise prices.” ‘^

The costs of violating price-fixing laws are very high: lawyers’ fees, government fines, poor morale, damaged public image, civil suits, and now prison terms.

While the appearance of price collusion or price fixing may seem bad in the energy market, and unproven, what will happen behind ‘closed doors’ for procedures outsourced in the NHS is likely to be a hidden scandal.

There is some truth in making the energy market more ‘competitive’. One, often rarely discussed solution, way is to ‘differentiate the product’, such that they are not all selling the same thing.

For such a homogeneous item such as gas, it is difficult to propose to do this.

Differentiating hernia operations, the bread-and-butter of the cherrypicked NHS for ‘high volume, low cost procedures’, is easier. You can vary the quality of en-suite ‘refreshments’. It’s well known that cinemas attract clients not on the basis of the quality of films, but on their range of things to go with their popcorn.

It may be intrinsically more easy to distinguish different ‘integrated care packages’, by varying the relative proportions of physical healthcare, social care, and social care (the components of what Andy Burnham MP might call “whole person care”).

The “we’ve been doing it for years” phenomenon of collusive practices is a tougher nut to crack. But in some fairness, the new private health providers haven’t been “doing it for years”, as the jet engines for the Health and Social Care Act (2012) for competitive tendering – the section 75 regulations – have only just been legislated for.

Amazingly enough, some producers of ‘folding boxes’ were given hefty fines in the United States in the 1970s. The experience there was that executives in the convicted paper companies acknowledge that the lack of contact between them and company lawyers made it hard to apply the law.

Direct contact between operating managers and members of the legal staff seemed to be less frequent in the companies that were more heavily involved in the conspiracy.

As they say, we live in ‘interesting times’, but, helpfully on this occasion, the experience from other jurisdictions may be quite helpful. Don’t blame me – Le Grand and Propper started it!

Will looking for blame in the ‘prime contractor model’ end up like one giant “pass-the-parcel”?

In a previous article of mine, “Outsourcing has become a policy drug, and they need to kick the habit”, I explained how the aspiration to have a smaller State had led to “reform” of the public services where the situation was now far worse.

Public money is being siphoned off into private sector shareholder dividends. Worse still, some performance monitoring of ongoing contracts is terrible. Furthermore, many outsourcing companies are currently embroiled in criminal allegations of one sort of another, mainly fraud.

It does seem a laudable aim to integrate healhcare (including mental health care) and social care. Indeed, by calling it ‘whole person care’, you temporarily get round the comparison to the ‘integrated shared care plans” of the United Staes.

The Health and Social Care Bill initially started life as the tr0jan horse of competitive markets into the NHS. Once this approach under Earl Howe blatantly fell apart, Norman Lamb was left to bring up the policy rear by talking about “integrated care”. However, the problem with integrated care is that it is yet again being launched as a launchpad for private providers to rustle together huge packages across a number of different areas through subcontracting.

Of course, one can argue that it’s great that a private provider can take control of so many different diverse services. But remember when the same argument was used to attack the NHS as ‘outdated’, ‘bloated’ and ‘Stalinist’? Such arguments for economies of scale or promotion of a coherent national health policy were jettisoned in favour of a fetish for introducing the market into the NHS at high speed. Unfortunately this policy has been totally discredited.

On the “prime contractor model”, the eminent health commentator Roy Lilley remarks:

Is this novel contacting or dumping the problem on someone else. Imaging trying to unpick a problem in the pathway. Everyone will blame someone else. This is a giant game of pass the parcel, isn’t it? The prime contractor may be accountable but they will pass the accountability up the line, delays will occur in getting answers. They will become a CCG-lite.

The prime contractor model involves a single organisation subcontracting work to other providers to integrate services across a pathway. A proportion of payments is dependent on the achievement of specific outcomes. Dozens of clinical commissioning groups are already said to be devising “innovative” contracts in which a lead provider receives an outcomes based payment to integrate an entire care pathway. For example, if the £120m deal is finalised, Circle ? which also runs Hinchingbrooke Health Care Trust ? will be financially and clinically accountable to commissioners for the whole pathway. The CCG said this previously involved 20 contracts across primary, secondary and community services. That news came after Bedfordshire CCG was named private company Circle as its preferred bidder to be “prime contractor” for an integrated musculoskeletal service.

Outsourcing companies don’t particularly appear to care what sectors they operate in, whether it’s in the running of healthcare, asylum seeking or probation services. Such an approach therefore lends itself easily to each citizen becoming a number not a name. The idea of us all having a special ‘services mastercard’ is not that far-fetched now, and if one day NHS budgeting is linked up with benefits, we’ll be yet closer to this ‘brave new world’.

In March 2012, G4S won a massive £30 million UK Border Agency contract to house asylum-seekers in the Midlands, the East of England, the North East, Yorkshire and Humberside. Using the “prime contractor model”, which G4S tells investors is “attractive”, the company granted subcontracts to UPM and the charity Migrant Help. And yet, in July 2013, Stephen Small, G4S managing director for Immigration and Borders, and Jeremy Stafford, Serco CEO for the UK and Europe were forced to defend their record before the Home Affairs Committee into the asylum system.

Serco’s evidence to the Committee revealed that in the North West it directly manages homes for asylum seekers through what the chair Keith Vaz described as ‘around twenty subcontractors from Happy Homes Ltd to First Choice Homes and Cosmopolitan Housing’.

Jeremy Stafford of Serco claimed this apparent recipe for housing management disaster was in fact a proven way of outsourcing and privatisation. It is ‘a very effective model and we do that in a number of the services we deliver’, he said.

This confidence in the ‘new delivery model’ of privatisation in the COMPASS contracts seems somewhat misplaced in the context of the JRF evidence. For it reveals that Reliance, the other security company with asylum housing contracts in London, the South West and Wales, sold on the privatised contracts after only two months to Capita and Clearel. The new provider, Clearel, did not fulfil the requirements of the contracts as tendered.

Only this week, the Serco boss quit. Four of the government’s biggest suppliers – G4S, Serco as well as rivals Capita and Atos – have been called to appear before a committee of British lawmakers next month for questioning about the outsourcing sector. Serco, which makes annual revenue of around 4.9 billion pounds, has continued to win deals in its other markets, such as a 335 million pound tie-up to run Dubai’s metro system, though it has encountered some problems abroad.

But back to G4S. There is even some reference to problems in the past on the G4s Welfare to Work website:

G4S Welfare to Work knows that most of the services needed to support workless people into meaningful, progressive employment in the UK already exist. What has been missing is an effective structure for managing and coordinating that provision.

… We are:

…

Operating a unique model for the delivery of welfare-to-work services that learns from mistakes made in previous Prime Contracting models, and builds on what works.

As I have described also in a previous article on this blog, one facet of globalisation is that it has become extremely difficult to regulate the behaviour of multinational corporations involved in healthcare.

G4s has now been ‘accused of “shocking” abuses and of losing control at one of South Africa’s most dangerous prisons‘. The South African government has temporarily taken over the running of Mangaung prison from G4S and launched an official investigation. It comes after inmates claimed they had been subjected to electric shocks and forced injections. G4S says it has seen no evidence of abuse by its employees. However, the BBC has obtained leaked footage filmed inside the high security prison, in which one can hear the click of electrified shields, and shrieking. It also shows a prisoner resisting a medication.

I have previously on this blog described the legal problems with the “prime contractor” model.

I have said before, and I will say it again. Especially since these contracts can be of such a long duration (for example, ten years), it is absolutely essential there are rigorous mechanisms for ongoing and continuous monitoring of performance. This way commissioners can spot easily and early on when providers are running into difficulties.

The English law gives a complex message on whether a private provider can still take the money and run, even if it doesn’t fulfill part of its side of the bargain in a contract.

Take for example the case of Sumpter v Hedges [1898] 1 QB 673 in the English Court of Appeal.

This was a matter where the plaintiff was contracted to erect certain buildings on the grounds of the defendant for a lump sum of 565 pounds, but the plaintiff was only able to do part of the work to a value of 333 pounds, with the defendant subsequently completing the rest of the work. As a result, the plaintiff sued on quantum meruit (as much as he or she has earned) appealing from the judgment of the trial judge who awarded the plaintiff for the value of the materials used, but nothing in respect to the work done.

The Court of Appeal upheld the trial judge’s decision and held that the plaintiff could not recover from the defendant in respect to the work done as part of quantum meruit due to the fact that the contract was for a lump sum, and there was no evidence that an agreement for part performance was formed.

While spinners are giving themselves multiple orgasms over ‘transparency and disclosure’ in the new Jerusalem of the NHS, it appears that “the fair playing field” of private and public health providers regarding basic patient safety is a complete fiasco.

Grahame Morris MP recently reviewed the gravity situation on the influential “Our NHS” website:

While public services are being outsourced to the private sector, especially in the NHS, Freedom of Information responsibilities are not following the public pound. Private health care companies can hide behind a cloak of commercial confidentiality when barely transparent contracts are awarded.

At the start of the bidding process private providers already receive a competitive advantage due to unequal disclosure requirements.

Private companies are free to use the Freedom of Information Act to gain detailed knowledge of a public sector provider, which can then be used to undercut or outbid the same public body when the contract is put out for tender.

NHS bodies must answer Freedom of Information requests relating to costs, performance and staffing. Yet a private provider has no similar duty of disclosure despite the fact they could have treated private patients for many years.

Once a contract is awarded, there is little that can be done if a private provider refuses to supply details to allow commissioning bodies to answer Freedom of Information requests. As they are not subject to Freedom of Information laws, the Information Commissioner has no power to investigate private contractors. They cannot serve notices for an investigation, and neither can they take enforcement action if a contractor destroys information or fails to comply with a request.

As a result of the decision in Sumpter and other similar decisions, the common law had subsequently recognised some exceptions to the general rule other than that performance of a contract must be exact and complete according to the terms. Furthermore, there is nothing preventing parties to a contractual relationship to vary or discharge the agreement, and can do so in a few ways.

One such way is “mutual discharge”, where both parties agree to release one another from what was agreed upon before either party has performed any of the acts promised. Another way is “release by one party”, where one party has completed their contractual promise, and agrees to release the other party from further performance of the contract.

Anyway, the “pass the parcel” analogy may not be entirely accurate.

It more be of the case that someone is holding a highly explosive bomb eight years into a ten year “prime contractor model” contract when it suddenly blows up.

And you can bet your bottom dollar that the Secretary of State for Health will definitely not be to blame.

Frailty: a critical test in reversing a ‘Fragmented Illness Service’ to a ‘National Health Service”?

Professionals intuitively recognise “frail” older people as more shrinked, and slowly moving. This phenotype is beautifully described by the Finnish painter Helene Schjerfbeck in the self-portraits up to her ninth decade. Increasingly, there has been a welcome policy move in recognising older individuals as a really valuable part of Society. The emphasis should be on ‘living well’, even with comorbidities. Some have rightly attacked blaming the ‘woes’ of the NHS on “the ageing population”.

The lack of definitive diagnostic criteria for ‘frail people’ through DSM or ICD has been a stumbling block, but professionals tend to recognise frail individuals when they see them. The thing not to do is to label all people who are above a certain age as “frail”: there are for example very many able and remarkably able people in their 80s and 90s.

And yet policy has failed to tackle this across many generations in English health policy, because other issues have been considered more urgent, such as A&E “waits”. When one problem appears to be getting solved, another one starts up. Some patients may feel that they will get a ‘better deal’ from a Trust which is observing the 4-hour wait, and prefer to be “blue-lighted” in an ambulance, than to wait for a more appropriate social care referral. Geriatricians are not considered the ‘cinderella service’ of the National Health Service, and care of the elderly wards have not traditionally been considered attractive for ‘high flying’ nurses or doctors, it is sometimes claimed.

This issue is not insubstantial. Out of an acute medical take of about 40-60 patients in one 24 hour period in a busy DGH or teaching hospital, by the law of averages, a handful will be ‘frail’ and then branded ‘social’. However, the needs of such patients should not be seen as a bureaucratic, administrative exercise on the acute medical take. These patients are important, as they are vulnerable for future ‘events’ involving acute medical care in the National Health Service (fragile may be a more physical counterpart of lack of resilience in wellbeing.) Clarity of vision and leadership are both critically needed. General Practitioners will often not need to visit a frail patient at home, unless something goes wrong. And yet when a frail patient ends up in hospital, say from having fallen over but not due to an obvious medical problem, the notes can be voluminous and unintelligible. At this point, the person becomes medicalised and gets plugged into the system at full force. So here is the first problem – when such a person ends up hospital, the communication between medical, psychiatric and social care services can be extremely poor. The care of the ‘frail person’ will be therefore a test case for the success of an integrated care service, when it finally appears.

All this does not mean ignoring the medical needs of the patient, but with a less ‘last minute approach’ investigations can be planned, like a 24-hour-tape or ECG if it is considered that a person is at risk of falling, for example. Tackling frailness indeed is what a person-centred care is designed for, some might say, and would help to enhance the dignity and perceived importance of care in older life. As both the Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Psychiatrists embrace ‘whole person care’, and while SCIE continue to lead on ‘personalisation’, the hope is that the person will be given proper attention in a less panicked way. This would help enormously on steering the “National Health Service” away from a situation where it becomes a lass-minute “Fragmented Illness Service”

The individual gets better ‘whole person care’. And it will in the long run also save money.

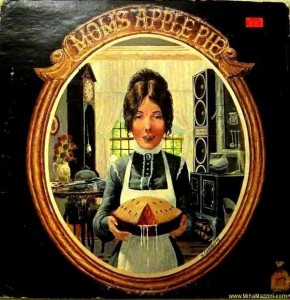

Andy Burnham’s “whole-person care” could be visionary, or it could be “motherhood and apple pie”

“Whole-Person Care” was at the heart of the proposal at the heart of Labour’s health and care policy review, formally launched yesterday, and presents a formidable task: a new “Burnham Challenge”?

It is described as follows:

“Whole-Person Care is a vision for a truly integrated service not just battling disease and infirmity but able to aspire to give all people a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being. A people-centred service which starts with people’s lives, their hopes and dreams, and builds out from there, strengthening and extending the NHS in the 21st century not whittling it away.” (more…)