Home » Posts tagged 'value'

Tag Archives: value

What’s best for a person isn’t necessarily what’s best for a hospital

It is pretty clear that the NHS as currently engineered puts Foundation Trusts on an elevated platform. Hospitals, being paid on the basis of activity involved for any one patient, can act for a sink for funding, when the health of any particular person is not easily matched to the aggregate level of activity for that person in a hospital.

The problem with ‘money following the patient‘ is it depends on whether you view it to be a success or failure that more money is spent on you the more ill you become. When a patient is admitted for an acute medical emergency in England, the care pathway can be pretty unambiguous. Most reasonable doctors on hearing about a history of cough, sputum and temperature, for a person with new breathing difficulties, on seeing the appropriate chest x-ray, would embark on a management of pneumonia; depending on the hospital, the course of antibiotics would be pretty standard from i.v. to oral, and the person would end up being discharged.

However, ‘activity based costing‘ and ‘payment by results‘ for hospital totally ignore the health of a person outside hospital. And if a healthcare model is to shift with time to ‘whole person care‘, what happens to a person outside of hospital is going to become increasingly important. If a person is better ‘controlled‘ for diabetes in the community, it is hoped that emergency admissions, such as for the diabetic ketocacidotic coma, can be avoided; or for example if a person is able to monitor their breathing peak flow in the community and notice the warning signs (such as a change in the colour of sputum), an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may be headed off at the pass.

Medicine is not an exact art or science, and the approach of ‘payment-by-results’, of a managerial accounting approach of activity-based costing, is at total odds to how decisions are actually made. Even in complex economics, within the last decade or so, the idea of “bounded rationality” has conceded that in decision-making, rationality of individuals is limited by the information they have, the cognitive limitations of their minds, and the finite amount of time they have to make a decision. Many ‘decision makers’ are not in fact perfectly rational, and it is likely that even the best doctors will differ in exact details for management of a patient in hospital for any given set of circumstances.

In health care, value is defined as the patient health outcomes achieved per pound spent. Value should be the pre-eminent goal in the health care system, because it is what ultimately matters for patients. Value encompasses many of the other goals already embraced in health care, such as quality, safety, patient centeredness, and cost containment, and integrates them.

However, despite the overarching significance of value in health care, it has not been the central focus.

The failures to adopt value as the central goal in health care and to measure value are arguably the most serious failures of the medical community.

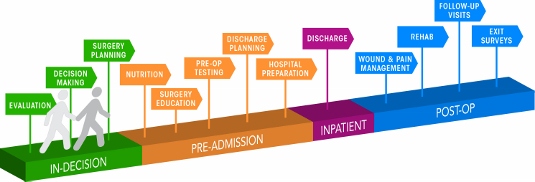

Health care delivery involves numerous organisational units, ranging from hospitals, to departments and divisions, to physicians’ practices, to units providing single services. The fundamental failing has been not to acknowledge how all these units interact in the “patient journey”.

In health care, needs for specialty care are determined by the patient’s medical condition. A medical condition is an interrelated set of patient medical circumstances — such as breast cancer, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, or congestive heart failure — that is best addressed in an integrated way. Therefore, a patient can be ‘plugged into the system’, as Mr X attending the specialist cystic fibrosis clinic at a local hospital. However, it is equally true to say that there are many patients with many different conditions, which interact either in disease process or treatment. And there are people who may later develop a medical illness who are perfectly well at any one ti,e.

For primary and preventive care, value could be measured for defined patient groups with similar needs. Patient populations requiring different bundles of primary and preventive care services might include, for example, healthy children, healthy adults, patients with a single chronic disease, frail elderly people, and patients with multiple chronic conditions. Each patient group has unique needs and requires inherently different primary care services which are best delivered by different teams, and potentially in different settings and facilities. However, life is clearly not so simple, and the beauty about the National Health Service is that it does not consider a person as the sum of his individual insurance packages.

Care for a medical condition (or a patient population) usually involves multiple specialties and numerous interventions. The most important thing here is that value for the patient is created not by any one particular intervention or specialty, but by the combined efforts of all of them. (he specialties involved in care for a medical condition may vary among patient populations. Rather than “focused factories” concentrating on narrow sets of interventions, we need integrated practice units accountable for the total care for a medical condition and its complications. To give as an example, optimal glucose control for diabetes in the community could possibly mean fewer referrals to the specialist eye clinic for the condition of diabetic retinopathy, an eye manifestation of diabetes, or to the vascular surgeon for a gangrenous toe requiring amputation.

A major barrier to delivering this care will be a fragmented, outsourced or privatised, NHS. In care for a medical condition, then, value for the patient is created by providers’ combined efforts over the full cycle of care — not at any one point in time or in a short episode of care. The only way to accurately measure value, then, is to track individual patient outcomes and costs longitudinally over the full care cycle. And this will be difficult the more care providers there are for any one patient.

Although outcomes and costs should be measured for the care of each medical condition or primary care patient population, current organisational structure and information systems make it challenging to measure (and deliver) value. Thus, most providers fail to do so. Providers tend to measure only the portion of an intervention or care cycle that they directly control or what is easily measured, rather than what matters for outcomes. For example, current measures often cover a single department (too narrow to be relevant to patients) or outcomes for a hospital as a whole, such as infection rates (too broad to be relevant to patients). Or providers measure what is billed, even though current reimbursement is for individual services or short episodes.

A way to get round this problem is to consider “indicators” which are are biological measures in patients that are predictors of outcomes, such as glycated hemoglobin levels (“HBA1c”) measuring blood-sugar control in patients with diabetes. Indicators can be highly correlated with actual outcomes over time, such as the incidence of acute episodes and complications. A HbA1c can be a good indicator of the compliance of an individual with diabetes with his or her medication or diet.

Indicators also have the advantage of being measurable earlier and potentially more easily than actual outcomes, which may be revealed only over time.

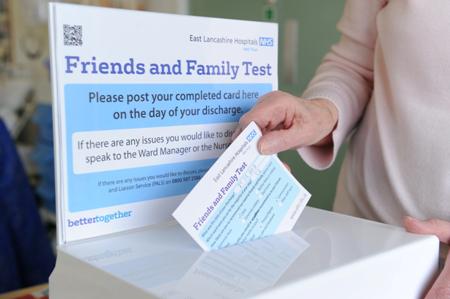

This is where over-focus on the wrong measure can be unhelpful. The launch of the ‘friends and family test’, which has seen an explosion of innovative technologies being sold to NHS Foundation Trusts over all the land, may be an important means of ensuring patient safety. Or it may not. We don’t know, as the data on this doesn’t exist.

However, patient satisfaction has multiple meanings in value measurement, with greatly different significance for value. It can refer to satisfaction with care processes. This is the focus of most patient surveys, which cover hospitality, amenities, friendliness, and other aspects of the service experience. Though the service experience can be important to good outcomes, it is not itself a health outcome. The risk of such an approach is that focusing measurement solely on friendliness, convenience, and amenities, rather than outcomes, can distract providers and patients from value improvement.

Value measurement in health care today in the English NHS is rather limited, and highly imperfect. Most physicians lack critical information such as their own rates of hospital readmissions, or data on when their patients returned to work. Not only is outcome data lacking, but understanding of the true costs of care is virtually absent. Most physicians do not know the full costs of caring for their patients — the information needed for real efficiency improvement.

In the recent target-driven culture of the English NHS, senior physicians are well aware of how length-of-stay has been gamed so there has been a ‘quick in and quick out’ mentality, seeing readmission rates for certain patients with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease sky-high.

At worst, what could have been a properly managed non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome ultimately ends up being a full-blown heart attack. Or what could have been a minor transient ischaemic attack ends up being a full-blown haemorrhagic stroke, causing a patient to be in a wheelchair and numerous healthcare teams looking after him or her.

Today, measurement focuses overwhelmingly on care processes. Processes are sometimes confused or confounded not only with outcomes, but with structural measures as well. Radiologists focus on the accuracy of reading a scan, for example, rather than whether the scan contributed to better outcomes or efficiency in subsequent care. Cancer specialists are trained to focus solely on survival rates, overlooking crucial functional measures in which major improvements vital to the patient are possible.

Cost is among the most pressing issues in health care, and serious efforts to control costs have been under way for decades. At one level, there are endless cost data at all levels of the system. However, as an ongoing project with Robert Kaplan makes clear, we actually know very little about cost from the perspective of examining the value delivered for patients.

Understanding of cost in health care delivery suffers from two major problems. The first is a cost-aggregation problem. Today, health care organisations measure and accumulate costs for departments, physician specialties, discrete service areas, and line items (e.g. supplies or drugs). As with outcome measurement, this practice reflects the way that care delivery is currently organised and billed for. Today each unit or department is typically seen as a separate revenue or cost centre. Proper cost measurement is challenging because of the fragmentation of entities involved in care.

To understand costs properly, they must be aggregated around the patient rather than for discrete services, just as is the case with outcomes. It is the total costs of providing care for the patient’s medical condition (or bundle of primary and preventive care services), not the cost of any individual service or intervention, that matters for value. If all the costs involved in a patient’s care for a medical condition — inpatient, outpatient, rehabilitation, physiotherapy, dietician, occupational therapy, diagnostic services, pharmacy, physician services, equipment, facilities — are brought together, it is then finally possible to compare the costs with the outcomes achieved.

Proper cost aggregation around the patient will allow us to distinguish charges and costs, understand the components of cost, and reveal the sources of cost differences.

Today, most physicians and provider organisations do not even know the total cost of caring for a particular patient or group of patients over the full cycle of care. There has been no reason to know, and Doctors resent turning their profession of medicine into one of bean-counting.

In aggregating costs around patients and medical conditions, we quickly arrive at the second problem: “the cost-allocation problem“. Many, even most, of the costs of health care delivery are shared costs, involving shared resources such as physicians, staff, facilities, equipment, and overhead functions involved in care for multiple patients. Even costs that are directly attributable to a patient, such as drugs or supplies, often involve shared resources, such as units involved in inventory management, handling, and set-up (e.g., the pharmacy). Today, these costs are normally calculated as the average cost over all patients for an intervention or department, such as an hourly charge for the operating room. However, individual patients with different conditions and circumstances can utilize the capacity of such shared resources quite differently.

The NHS in England has latterly become obsessed by its “funding gap”. Much health care is delivered in over-resourced facilities. Routine care, for example, is delivered in expensive hospital settings. Expensive space and equipment is underutilised, because facilities are often idle and much equipment is present but rarely used. Skilled physicians and staff spend much of their time on activities that do not make good use of their expertise and training. It is not uncommon for junior doctors to end up spending hours in a hospital taking blood, putting in catheters, or putting in venflons.

It is likely that ‘payment-by-results’ will at some stage have to go. Reimbursement should cover a period that matches the care cycle. For chronic conditions, bundled payments should cover total care for extended periods of a year or more. Aligning reimbursement with value in this way rewards providers for efficiency in achieving good outcomes while creating accountability for substandard care.

Improvements in outcomes and cost measurement will greatly ease the shift to bundled reimbursement and produce a major benefit in terms of value improvement. Current organisational structures, practice standards, and reimbursement create obstacles to value measurement, but there are promising efforts under way to overcome them.

The “payment-by-results” model is a complete anethema to how decisions are made in the real world. Prospect theory is a behavioral economic theory that describes the way people choose between probabilistic alternatives that involve risk, where the probabilities of outcomes are known. The theory states that people make decisions based on the potential value of losses and gains rather than the final outcome, and that people evaluate these losses and gains using certain heuristics. The model is descriptive: it tries to model real-life choices, rather than optimal decisions. The theory was developed by Daniel Kahneman, a professor at Princeton University’s Department of Psychology, who won the Nobel Prize for economics in 2002.

It is a pity that the payment-by-results ideology has been so overwhelming, perhaps powerfully pushed for by the accountants and management consultants wishing to drive ‘efficiency’ in the NHS, taking the media with them on this escapade. However, it is poorly aligned to how healthcare, psychiatric care and social care professionals make decisions in the real world.

Critics will correctly argue that value is notoriously difficult to measure, and might be virtually impossible to measure across a ‘care cycle’. Indeed the original criticism of the Kaplan and Cooper (1992) account of ‘activity based costing’ warned against organisations allocating excessive resources to collecting information which they are then able to make use of properly.

We are quickly coming to an age where it is going to be a ‘good outcome’ to keep a frail patient out of hospital through high quality care in the community through integrated teams. By that stage, the ideological shift from cost to value will have needed to have taken place, and funding models will have to reflect more the drive towards value and ultimate clinical outcome.

The “Everyday” “stack-em-high” approach may not work for all parts of the NHS

Right-wing commentators always attack the NHS by saying that it mustn’t be treated as a “sacred cow”, like a “national religion”. The public don’t wish to see it as a business either. I have no idea what the majority of members of the Royal College of Surgeons think.

The "everyday" "stack-em-high" culture clearly doesn't work for all of the NHS

Right-wing commentators always attack the NHS by saying that it mustn’t be treated as a “sacred cow”, like a “national religion”. The public don’t wish to see it as a business either. It is not surprising that the Royal College of Surgeons as a College are in favour of the “reforms” increasing the scope for private provision, but most surgeons were indeed also trained by the NHS.

So, if it’s not a business, why are they such pains to keep the NHS branding and logo then? The lettering (even the font, size, colour and slant) is known on the national trademarks register, so is the exact Pantone colour. Why are Virgin and Circle not keen to get rid of the NHS branding and do all their NHS services in their own brand? This is simple. It’s because the NHS brand is incredibly strong, so much so that successive governments have wished to export it.

Tesco everyday burgers contain “no artificial preservatives, flavours or colours”, except some contained horsemeat apparently. Not being able to see inside the box with the benefit of a DNA reader is possibly to blame, but which corporate supplier is providing your hernia operation in future may not be so easy to tell in future either.

One thing is absolutely certain about the NHS “reforms”. It is most definitely a “top-down reorganisation”, it will not address the numerous concerns of the Francis Report, and it gives a clear green light to outsourcing a far greater number of contracts to private sector suppliers who are very slick at producing bids. Even the most unintelligent of spokespeople for the Conservatives’ policy, both official and unofficial, openly concede that it is hard to provide a service that is comprehensive and bitty through this route.

That’s why it best for the profitability of shareholders that the product is delivered in a short-sharp-shock, like an abdominal hernia repair, or a Tesco “everyday burger” containing horsemeat. They choose what offerings they wish to produce. Whilst the Ed Miliband conference speech on ‘predators and producers’ was on-the-whole “panned”, the new healthcare market is perfect for private equity investors. Their freedom to operate in a “liberalised market” is only constrained by the legal and regulatory constraints placed upon them. You can argue “til the cows come” home whether the abolition of the Foods Standards Authority created a climate for such cutting corners to occur – or maybe that should be “til the horses come home”.

While it’s well known that some high street firms have struggled, it’s noticeable that “value brands”, including Tesco everyday value items and Aldi, and “luxury” brands have withstood the recession quite well. There is of course no real market in healthcare, of people “shopping around”, with a customer not paying directly to the supplier of the healthcare product, the supplier using the NHS branding away, and dodgy metrics to judge the ‘quality’ of a healthcare intervention largely dreamt up by a busybody who has never set foot on a busy NHS ward.

However, that the NHS could offer its equivalent of “value” products, but not to enhance shareholder dividend, but for the benefit of treating as many people as possible efficiently to the highest of rigorous medical and nursing standards is a worthy cause. An unfortunate effect of the reaction to the Tesco “horsemeat” saga is that rather demeaning judgements about people who buy “everyday” products have entered through the back door. However, many people are desperately keen to avoid an emergence of a “two tier” service in healthcare where access-to-medical-treatment becomes dependent upon an ability-to-pay.

It’s possible that at the “everyday” end of the NHS, it might be possible to go for the “stack them high” approach which is pervading education and healthcare, which is perfect for private equity investors. However, this system is clearly not ideal for all, and this is clear not a market led by the “end-consumer”. Characteristics of markets where there is poor competition due to lack of participants include an inability of customers to lower prices and an ability for suppliers to increase prices, while providing the essentially the same product. This is what has happened in a whole string of privatised industries, including gas, electricity, water and railways, and the (relatively) “simple” hernia operation is going to be no different. Whose going to benefit from offering a contracted core NHS service? Of course, the corporates whom I don’t dare to name because of their legal teams. Will the patient benefit compared to a NHS ideal of “comprehensive” and “free-at-the-point-of-use”? Absolutely not.

Blogpost: "Blogging Against Disablism Day 2012" – my experience #BADD2012

The seventh annual Blogging Against Disablism day is today, on Tuesday, 1st May 2012. This is the day where all around the world, disabled and non-disabled people blog about their experiences, observations and thoughts about disability discrimination. In this way, we hope to raise awareness of inequality, promote equality and celebrate the progress we’ve made. I once wrote a post for the legal blog, Legal Cheek, describing the practical difficulties that disabled students like me, have in training contract interviews. But this is a different post!

I have often written on this blog about inclusivity and accessibility in relation to law and legal education; and I strongly recommend their twitter thread @legalcheek.

Actually, the firms on the whole are very good at making you feel comfortable for the interview. So much so you end up feeling very uncomfortable (as a result of the ‘Does he take sugar?’ syndrome). However, I would say almost too comfortable, in the sense that you do feel that the Partners concerned were taking meticulous care. In a sense, this is a case of ‘damned if you do, or damned if you don’t’.

My disability is multi-fold. I see double all the time, therefore I often voluntarily have to shut one eye to avoid seeing double. This is because I was in a coma for six weeks in the summer of 2007 due to meningitis. I now have also a cerebllar dysarthria (speech problem), but I am told that my speech is comprehensible. Secondly, I have trouble walking. I have a condition which is known as ataxia, which means I can easily go off balance, and I look as if I am mildly drunk. I find that London cabbies immediately know that I have ataxia, even if I hail a cab from outside a pub (I do not drink alcohol any more); they are very discerning, and, of course they have a right to refuse to pick you up if they wish and they can justify it. The handicap means I have to take it steady while walking (I won’t be doing the London Legal Walk 2012, but the organisers have kindly given me the chance to do sponsored tweeting for it, which makes me very happy as I volunteered for 5 months last year in a law centre in London in welfare benefits, as a law student approved to do the LPC).

I think for training contract interviews, some candidates do not even know that they require ‘reasonable adjustments’. I am very influenced by David Merkel, the lawyer in charge of the Law Society’s ‘Lawyers with Disabilities’ group. I went to their Christmas bash in 2010, and David told me, at a quiet moment aside, it was all about giving law students ‘a chance to show what they can add to a law firm, on a level playing field‘.This I feel is very true. Disabled citizens like me don’t like being made to feel ill, which they can sometimes do in the application procedure for training contracts. They’re not ill, they’re just different. Unfortunately, this Government, which stopped my Disabled Living Allowance without any warning or notification, makes me feel unwanted. I refuse to allow that perception of me, even if Katie Hopkins makes hurtful tweets like this. I cried for a bit after I read it, but with all due respect having completed my MBA recently I feel confident about business too, but in a different sense. I am 37, with several good postgraduate degrees, including in business, law and natural sciences, so I feel that I can bring value to society, even more than a popular TV show. Ironically, I feel @Lord_Sugar appreciates ‘value’ in business.

Finally, I am most grateful to @BADDTweets for alerting me to this, which is the Twitter stream for “Blogging Against Disablism Day”, run by @goldfish and @themanoutside (#bad2012): http://tinyurl.com/BADD2012. I particularly appreciate the chance to voice my experience of disability and disabilism here. All I can say to disabled and non-disabled citizens that it can be, in any context, very insidious and subtle. I am very lucky in that the law school I’m in does not “make me feel ill” (in any way you wish to interpret this legally or not!), but rather instead wanted and valued, and it is a joy to study my Legal Practice Course at BPP Law School, Holborn.

Why the NHS Health and Social Care Bill doesn’t make sense to me

This post is inspired by brief discussions I’ve had with Sunny Hundal where Sunny asked me lots of questions I couldn’t answer!

Of course, Labour is clear that they oppose the NHS Health and Social Care Bill. What they had not been clear to me about is why they oppose it, though I am very grateful to Sunny Hundal for pointing me in the direction of the ‘Drop the Bill’ website which establishes five important alleged concerns of the Bill: postcode lottery, longer waiting times, privatisation, damaged doctor-patient relationship, and waste.

Labour and supporters bandy around the statement ‘It is privatising the NHS’. This is indeed a very good way of looking at it, as the fundamental thesis is that there will be a greater role for the private sector in the provision of health services for England. To ignore the existing contribution of the private sector in the NHS is complete nonsense, however. NHS budgets operate millions of pounds, and the private sector is clearly involved. Most people in the general public have heard of NHS procurement, or “NHS logistics”; many people, in both the private and public sector are somehow enmeshed in the NHS ‘supply chain’. In fact, at least with privatisation, according to the aspiration of Baronesss Thatcher, there is public ownership of the infrastructure. The worrying aspect here is that NHS entities can be bought by hedge funds or even foreign investors, as part of a multinational investment, and indeed Ed Miliband might be right after all – corporate entities might wish to sell bits off the NHS ‘for a quick buck’ in his much derided speech on corporate social responsibility last year. There is as such not illegal, but many will not agree with this sensitive corporate handling of key infrastructure assets.

A more mature intelligent debate is to consider why precisely the NHS Health and Social Care Bill does not make sense. It firmly places the NHS in private hands, and it is worth scrutinising carefully at this point what the legal entity of the NHS Trust is.

If it is a private limited company under law, it is under legal obligation to maximise shareholder dividend, and the question then becomes who exactly are the shareholders, and how will their profits from NHS patients be used? One assumes that NHS Trusts will be subject to all aspects of company law, such as insolvency law and competition law inter alia. How is competition going to work? And are entities going to offer products or services that are ‘profitable’? What about dementia, for example? I am worried about the fact that this could lead to major imbalances in service provision at both primary care level and in NHS Trusts. How is the Tory-led Government going to ensure that apples are not unfairly compared to bananas in this new free market of the NHS? This involves a complex understanding of how products and services are going to be costed in the new NHS; will they be simply the cost of providing the products or services, or will some corporate entities wish to undercut other suppliers by ‘penetration pricing'; or will some suppliers price themselves at a high price to denote high brand value, for example for ‘the best hip operation in town’? For that matter, how does the Bill deal with measuring benefits and outcomes for the patient, rather than the corporate supplier?

I believe strongly that we will almost have to invent a new entity in law to cover NHS trusts, if it is not the private limited company or charity under the Companies Act or Charities Act. I do not feel that such strategic change will succeed in management for one clear reason, anyway. In any such rushed strategic change, you must have follower support; so even if the LibDems in the lower and upper Houses act as the lubricant for the Conservative engine in allowing this Bill a clear path to Royal Assent, the implementation of the NHS Bill will almost certainly fail due to lack of support from many GPs, the Royal Colleges, many other health staff, and most importantly the patient. I also feel that, in management, it is going to impossible to implement such organisational structural and cultural change in such a hurry.

Calling the BMA a ‘trade union’ itself is not a trivial point. Trade Unions protect the rights of employees rather than shareholders (unless stakeholders are also shareholders), and therefore if the NHS Bill is enacted without key stakeholder support it will fail. This is because the members of this trade union are not involved in the strategic change process at all well, and feel it is being inflicted without their consent. They also will have much tacit implicit knowledge about the NHS, as well as codified principles, which will be harder to shift without specialist change managers.

However, there is no doubt that somebody does need to look at the management structure of the NHS, which is why I should rather Labour has a constructive input into the debate, on behalf of public sector workers, and if it decides it wishes for blanket obstruction, it should consider urgently an alternative, because it is currently the case there are parts of the NHS which are financial disaster zones. Furthermore, the NHS does not always work well; very many nurses work with poor pay and conditions, but stories about suboptimal care unfortunately do rumble on (especially in elderly care). Finally, there is a strong part of me that believes in a system where we all share risk in a National Health Service by paying a contribution – this is where reform of the tax system is vital, as the NHS is currently paid for out of income tax mainly to my knowledge. If private enterprises are allowed wholly to run the NHS, it could be that the business entities which go out of business are those where there are particular ‘hotspots’ of disease due to an unfortunate combination of nature and nurture, for example chronic obstructive airways disease in coal miners in Wales, or high incidence of cardiovascular disease in Bengali immigrants in Tower Hamlets. Health inequalities are a serious problem for medical care, and replacement of the NHS with increased private input for entities to run at a profit would be a serious threat to that.

That’s the sort of debate I wish for why I oppose the NHS Health and Social Care Bill. And what about Dilnot also?

This is a personal view of @legalaware, and does not represent the views of the BPP Legal Awareness Society, nor of BPP.

Book review: Socialnomics, Word of mouth for social good, by Erik Qualman (@Qualman)

The associated website of ‘Socialnomics’ is http://www.socialnomics.net/.

This book surrounds a huge mystery surrounding social value. The easiest question to ask is what is the cost of social media? Apart from the investment in the necessary computer hardware, the answer is ‘virtually nothing’. Erik Qualman devotes the entire book to discovering the value of social media for both individuals and businesses, and is a very engaging and impressively researched contribution to the field.

Whilst there is a relatively short formal section on ‘return on investment’, the book has its focus why people could possibly benefit from an involvement with social media. Like the nature of these innovative technologies themselves, this book is more than a simple invention. Like the importance of this book, the value of social media, according to Qualman’s thesis, ultimately arises from the quality of the interaction of the user with the product.

The book is surprisingly flexible in the possibilities that the reader might wish to adopt after reading this book, although there is one useful ‘socialnomics’ diagram which could be used as a basic framework. The actual business models of social media such as Facebook and Twitter have been evasive, even for the management of these companies in real life, so it would be unfair to expect Qualman to produce a definitive answer about this. There are some real ‘unexpected gems’, such as the possible ‘unique selling proposition’ of people who are experts in particular areas getting their 15 minutes (or beyond) on Twitter. I was particularly intrigued about the use of Twitter in easing communication between different generations of Twitter. I find this ‘democratisation’ of society through the social media extremely attractive, where every person’s opinion is highly valued, irrespective of social rank. This could be a potent theme in thinking how businesses interact in a dialogue with their clients, for example in law and business.

Qualman’s question is fundamentally a problematic one – what is the value of ‘socialnomics’? How or why might it go further than face-to-face real-life interactions. It is impossible to argue that the book lacks structure. The book in a very systematic way segments the discussion into relevant areas, but certain chapters (such as the use of social media in Obama’s electoral campaign) may not be that interesting to all readers in the UK. The book is founded on a plethora of interesting facts and opinions, and the case examples are relevant and interesting. For example, Qualman visits the notion of the ‘expert blogger’, and provides a very elegant and compelling argument why the “expert” blogger might be more impressive than the “expert” journalist in a prestigious newspaper. Qualman also reviews in a meaningful way the complicated world of Twitter, considering what might be of value in a 140 character tweet, and considers the advantages of real-time interaction in platforms such as Twitter and 4square, say, for example, compared to Facebook.

A possible limitation of this book is the answer to the question, “Can you show me the money?” This is where I feel that Qualman does not go into ‘hard sell’ of his undoubtedly considerable expertise in how to ‘make’ the customer benefit from the social media. Qualman sticks to a very interesting story about the possible impact of social media on society and its economy, instead of immersing himself in a turgid analysis based on international marketing principles which might have added little to the reader’s understanding. Instead, he allows in a very pleasant way the reader to make his or her own mind up, about what might work for him or her. Anyone who says otherwise, I feel, is exhibiting some sort of ‘book envy’.

I am not aware of any book like it, which provides a comprehensive understandable overview of the world of social media, for both personal and business user. It’s available in a number of formats, including audiobook, hard copy book, and of course a form which you can read on your #ipad2. Like is true for the whole social media industry, and corporate entities such as law firms, the ultimate goal is to find those new customers.