It is pretty clear that the NHS as currently engineered puts Foundation Trusts on an elevated platform. Hospitals, being paid on the basis of activity involved for any one patient, can act for a sink for funding, when the health of any particular person is not easily matched to the aggregate level of activity for that person in a hospital.

The problem with ‘money following the patient‘ is it depends on whether you view it to be a success or failure that more money is spent on you the more ill you become. When a patient is admitted for an acute medical emergency in England, the care pathway can be pretty unambiguous. Most reasonable doctors on hearing about a history of cough, sputum and temperature, for a person with new breathing difficulties, on seeing the appropriate chest x-ray, would embark on a management of pneumonia; depending on the hospital, the course of antibiotics would be pretty standard from i.v. to oral, and the person would end up being discharged.

However, ‘activity based costing‘ and ‘payment by results‘ for hospital totally ignore the health of a person outside hospital. And if a healthcare model is to shift with time to ‘whole person care‘, what happens to a person outside of hospital is going to become increasingly important. If a person is better ‘controlled‘ for diabetes in the community, it is hoped that emergency admissions, such as for the diabetic ketocacidotic coma, can be avoided; or for example if a person is able to monitor their breathing peak flow in the community and notice the warning signs (such as a change in the colour of sputum), an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may be headed off at the pass.

Medicine is not an exact art or science, and the approach of ‘payment-by-results’, of a managerial accounting approach of activity-based costing, is at total odds to how decisions are actually made. Even in complex economics, within the last decade or so, the idea of “bounded rationality” has conceded that in decision-making, rationality of individuals is limited by the information they have, the cognitive limitations of their minds, and the finite amount of time they have to make a decision. Many ‘decision makers’ are not in fact perfectly rational, and it is likely that even the best doctors will differ in exact details for management of a patient in hospital for any given set of circumstances.

In health care, value is defined as the patient health outcomes achieved per pound spent. Value should be the pre-eminent goal in the health care system, because it is what ultimately matters for patients. Value encompasses many of the other goals already embraced in health care, such as quality, safety, patient centeredness, and cost containment, and integrates them.

However, despite the overarching significance of value in health care, it has not been the central focus.

The failures to adopt value as the central goal in health care and to measure value are arguably the most serious failures of the medical community.

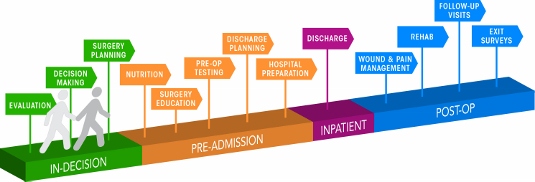

Health care delivery involves numerous organisational units, ranging from hospitals, to departments and divisions, to physicians’ practices, to units providing single services. The fundamental failing has been not to acknowledge how all these units interact in the “patient journey”.

In health care, needs for specialty care are determined by the patient’s medical condition. A medical condition is an interrelated set of patient medical circumstances — such as breast cancer, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, or congestive heart failure — that is best addressed in an integrated way. Therefore, a patient can be ‘plugged into the system’, as Mr X attending the specialist cystic fibrosis clinic at a local hospital. However, it is equally true to say that there are many patients with many different conditions, which interact either in disease process or treatment. And there are people who may later develop a medical illness who are perfectly well at any one ti,e.

For primary and preventive care, value could be measured for defined patient groups with similar needs. Patient populations requiring different bundles of primary and preventive care services might include, for example, healthy children, healthy adults, patients with a single chronic disease, frail elderly people, and patients with multiple chronic conditions. Each patient group has unique needs and requires inherently different primary care services which are best delivered by different teams, and potentially in different settings and facilities. However, life is clearly not so simple, and the beauty about the National Health Service is that it does not consider a person as the sum of his individual insurance packages.

Care for a medical condition (or a patient population) usually involves multiple specialties and numerous interventions. The most important thing here is that value for the patient is created not by any one particular intervention or specialty, but by the combined efforts of all of them. (he specialties involved in care for a medical condition may vary among patient populations. Rather than “focused factories” concentrating on narrow sets of interventions, we need integrated practice units accountable for the total care for a medical condition and its complications. To give as an example, optimal glucose control for diabetes in the community could possibly mean fewer referrals to the specialist eye clinic for the condition of diabetic retinopathy, an eye manifestation of diabetes, or to the vascular surgeon for a gangrenous toe requiring amputation.

A major barrier to delivering this care will be a fragmented, outsourced or privatised, NHS. In care for a medical condition, then, value for the patient is created by providers’ combined efforts over the full cycle of care — not at any one point in time or in a short episode of care. The only way to accurately measure value, then, is to track individual patient outcomes and costs longitudinally over the full care cycle. And this will be difficult the more care providers there are for any one patient.

Although outcomes and costs should be measured for the care of each medical condition or primary care patient population, current organisational structure and information systems make it challenging to measure (and deliver) value. Thus, most providers fail to do so. Providers tend to measure only the portion of an intervention or care cycle that they directly control or what is easily measured, rather than what matters for outcomes. For example, current measures often cover a single department (too narrow to be relevant to patients) or outcomes for a hospital as a whole, such as infection rates (too broad to be relevant to patients). Or providers measure what is billed, even though current reimbursement is for individual services or short episodes.

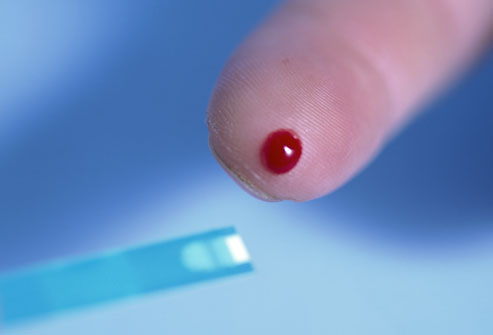

A way to get round this problem is to consider “indicators” which are are biological measures in patients that are predictors of outcomes, such as glycated hemoglobin levels (“HBA1c”) measuring blood-sugar control in patients with diabetes. Indicators can be highly correlated with actual outcomes over time, such as the incidence of acute episodes and complications. A HbA1c can be a good indicator of the compliance of an individual with diabetes with his or her medication or diet.

Indicators also have the advantage of being measurable earlier and potentially more easily than actual outcomes, which may be revealed only over time.

This is where over-focus on the wrong measure can be unhelpful. The launch of the ‘friends and family test’, which has seen an explosion of innovative technologies being sold to NHS Foundation Trusts over all the land, may be an important means of ensuring patient safety. Or it may not. We don’t know, as the data on this doesn’t exist.

However, patient satisfaction has multiple meanings in value measurement, with greatly different significance for value. It can refer to satisfaction with care processes. This is the focus of most patient surveys, which cover hospitality, amenities, friendliness, and other aspects of the service experience. Though the service experience can be important to good outcomes, it is not itself a health outcome. The risk of such an approach is that focusing measurement solely on friendliness, convenience, and amenities, rather than outcomes, can distract providers and patients from value improvement.

Value measurement in health care today in the English NHS is rather limited, and highly imperfect. Most physicians lack critical information such as their own rates of hospital readmissions, or data on when their patients returned to work. Not only is outcome data lacking, but understanding of the true costs of care is virtually absent. Most physicians do not know the full costs of caring for their patients — the information needed for real efficiency improvement.

In the recent target-driven culture of the English NHS, senior physicians are well aware of how length-of-stay has been gamed so there has been a ‘quick in and quick out’ mentality, seeing readmission rates for certain patients with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease sky-high.

At worst, what could have been a properly managed non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome ultimately ends up being a full-blown heart attack. Or what could have been a minor transient ischaemic attack ends up being a full-blown haemorrhagic stroke, causing a patient to be in a wheelchair and numerous healthcare teams looking after him or her.

Today, measurement focuses overwhelmingly on care processes. Processes are sometimes confused or confounded not only with outcomes, but with structural measures as well. Radiologists focus on the accuracy of reading a scan, for example, rather than whether the scan contributed to better outcomes or efficiency in subsequent care. Cancer specialists are trained to focus solely on survival rates, overlooking crucial functional measures in which major improvements vital to the patient are possible.

Cost is among the most pressing issues in health care, and serious efforts to control costs have been under way for decades. At one level, there are endless cost data at all levels of the system. However, as an ongoing project with Robert Kaplan makes clear, we actually know very little about cost from the perspective of examining the value delivered for patients.

Understanding of cost in health care delivery suffers from two major problems. The first is a cost-aggregation problem. Today, health care organisations measure and accumulate costs for departments, physician specialties, discrete service areas, and line items (e.g. supplies or drugs). As with outcome measurement, this practice reflects the way that care delivery is currently organised and billed for. Today each unit or department is typically seen as a separate revenue or cost centre. Proper cost measurement is challenging because of the fragmentation of entities involved in care.

To understand costs properly, they must be aggregated around the patient rather than for discrete services, just as is the case with outcomes. It is the total costs of providing care for the patient’s medical condition (or bundle of primary and preventive care services), not the cost of any individual service or intervention, that matters for value. If all the costs involved in a patient’s care for a medical condition — inpatient, outpatient, rehabilitation, physiotherapy, dietician, occupational therapy, diagnostic services, pharmacy, physician services, equipment, facilities — are brought together, it is then finally possible to compare the costs with the outcomes achieved.

Proper cost aggregation around the patient will allow us to distinguish charges and costs, understand the components of cost, and reveal the sources of cost differences.

Today, most physicians and provider organisations do not even know the total cost of caring for a particular patient or group of patients over the full cycle of care. There has been no reason to know, and Doctors resent turning their profession of medicine into one of bean-counting.

In aggregating costs around patients and medical conditions, we quickly arrive at the second problem: “the cost-allocation problem“. Many, even most, of the costs of health care delivery are shared costs, involving shared resources such as physicians, staff, facilities, equipment, and overhead functions involved in care for multiple patients. Even costs that are directly attributable to a patient, such as drugs or supplies, often involve shared resources, such as units involved in inventory management, handling, and set-up (e.g., the pharmacy). Today, these costs are normally calculated as the average cost over all patients for an intervention or department, such as an hourly charge for the operating room. However, individual patients with different conditions and circumstances can utilize the capacity of such shared resources quite differently.

The NHS in England has latterly become obsessed by its “funding gap”. Much health care is delivered in over-resourced facilities. Routine care, for example, is delivered in expensive hospital settings. Expensive space and equipment is underutilised, because facilities are often idle and much equipment is present but rarely used. Skilled physicians and staff spend much of their time on activities that do not make good use of their expertise and training. It is not uncommon for junior doctors to end up spending hours in a hospital taking blood, putting in catheters, or putting in venflons.

It is likely that ‘payment-by-results’ will at some stage have to go. Reimbursement should cover a period that matches the care cycle. For chronic conditions, bundled payments should cover total care for extended periods of a year or more. Aligning reimbursement with value in this way rewards providers for efficiency in achieving good outcomes while creating accountability for substandard care.

Improvements in outcomes and cost measurement will greatly ease the shift to bundled reimbursement and produce a major benefit in terms of value improvement. Current organisational structures, practice standards, and reimbursement create obstacles to value measurement, but there are promising efforts under way to overcome them.

The “payment-by-results” model is a complete anethema to how decisions are made in the real world. Prospect theory is a behavioral economic theory that describes the way people choose between probabilistic alternatives that involve risk, where the probabilities of outcomes are known. The theory states that people make decisions based on the potential value of losses and gains rather than the final outcome, and that people evaluate these losses and gains using certain heuristics. The model is descriptive: it tries to model real-life choices, rather than optimal decisions. The theory was developed by Daniel Kahneman, a professor at Princeton University’s Department of Psychology, who won the Nobel Prize for economics in 2002.

It is a pity that the payment-by-results ideology has been so overwhelming, perhaps powerfully pushed for by the accountants and management consultants wishing to drive ‘efficiency’ in the NHS, taking the media with them on this escapade. However, it is poorly aligned to how healthcare, psychiatric care and social care professionals make decisions in the real world.

Critics will correctly argue that value is notoriously difficult to measure, and might be virtually impossible to measure across a ‘care cycle’. Indeed the original criticism of the Kaplan and Cooper (1992) account of ‘activity based costing’ warned against organisations allocating excessive resources to collecting information which they are then able to make use of properly.

We are quickly coming to an age where it is going to be a ‘good outcome’ to keep a frail patient out of hospital through high quality care in the community through integrated teams. By that stage, the ideological shift from cost to value will have needed to have taken place, and funding models will have to reflect more the drive towards value and ultimate clinical outcome.

Pingback: The “official top 40″ of my most viewed articles on the SHA website this year()

Pingback: Care at the crossroads. Burnham has something big, and you may be quite pleased to see him()