Home » Posts tagged 'reform'

Tag Archives: reform

NHS Privatisation: The end-game

where you see * you can click to the hyperlink to bring you to the original website source of the direct quote.

I was recently reminded of a debacle under a Labour government in 2006 which the Guardian reported as follows*:

“A secret plan to privatise an entire tier of the NHS in England was revealed prematurely yesterday when the Department of Health asked multinational firms to manage services worth up to £64bn.

The department’s commercial directorate placed an advertisement in the EU official journal inviting companies to begin “a competitive dialogue” about how they could take over the purchasing of healthcare for millions of NHS patients. …

The advertisement asked firms to show how they could benefit patients if they took over responsibility for buying healthcare from NHS hospitals, private clinics and charities. The plan would give private firms responsibility for deciding which treatments and services would be made available to patients – and whether NHS or private hospitals would provide them.” (The Guardian)

“How to create money” in the NHS has always been one about denigrating the views of its professional social capital, and thinking about ways of maximising income.

As we approach the ‘E day’, May 7th 2015, when we know that the UK will go to the polls, it is useful to consider now the end-game of NHS privatisation.

False reassurances have been a-plenty.

Privatisation, when you apply common sense, is simply diversion of resources into the private sector from the public sector. Outsourcing (enacted through section 75 Health and Social Care Act (2012) and its regulations) is a key part of that.

But it’s not the full story. You’d have to be a complete idiot to wish to maintain that the NHS is not being privatised.

Some people, it seems, are prepared to perform that rôle.

The end-game

Nearly a year ago, before the section 75 regulations had been discussed in parliament, I introduced here how this somewhat ignored clause would fix the NHS into a competitive market.

I wrote a blogpost on the predictable trajectory of the NHS privatisation which clearly argues that this had started with shifts in policy from the Thatcher and Major governments.

If you want to understand the model, it’s worth tracking it back to the horses’ mouths: Conservative MPs Mr John Redwood and Dr Oliver Letwin.

In a now seminal article, “Opening the oyster: the 2010-1 NHS reforms in England” by academics Dr Lucy Reynolds and Prof Martin McKee for the Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London (2012), known as “Clinical medicine”, the background to this journey to full privatisation is laid bare [Clin Med, April 1, 2012 vol 12 no 2, pp. 128-132.]

Reynolds and McKee argue in their conclusion*:

“Enthoven’s description of the HMO model, which he explicitly stated was at least as problematic but more expensive than the NHS, has somehow been adopted as a blueprint for the privatisation of the NHS. It was recently reported that the newer ‘accountable care model’ now finds favour with the secretary of state for health. This flexible model is a successor to the HMO model, although it is not greatly different in concept or operation. It involves a managed care arrangement in which the private sector primary care gatekeeper receives a subsidy from the government to pay all or part of the individual premiums due for the people registered with it, with the individuals concerned expected to pay any shortfall between the personal budgets provided by government and the amount charged by the accountable care organisation.

… Fulfilment of the longstanding ambition, documented by Redwood and Letwin, to expand private financing of the healthcare system through user contributions is thus now imminent. Enthoven’s reasoned view that market-based healthcare provision is more expensive and less universal than the NHS system consistently has been overlooked. …” (Reynolds and McKee, 2012)

“Commissioning support units” are for the time-being part of the new NHS landscape. Here they are discussed by Veronika Thiel on the King’s Fund website (linking to an article in the HSJ)*:

“Commissioning support units are set to take on important functions in the new NHS structure. They will support clinical commissioning groups by providing business intelligence, health and clinical procurement services, as well as back-office administrative functions, including contract management.” (Thiel, King’s Fund website)

The immediate future steps are something like this:

1. CSUs spun off as private entities, to private equity firms.

2. CSUs provide support to CCGs.

3. CCGs commission services from providers.

4. Each of us given a voucher worth what it is predicted we will cost.

5. We then exercise our choice to find an option that meets our expectations.

6. If the value of our voucher is insufficient, we top it up ourselves.

7. There’s some safety net for the very poor perhaps (and there’s a bit of lee-way here for anti-immigration politics).

8. CCGs compete with each other.

Commissioning support units and private equity

Roy Lilley, a health commentator, only this week reported on the big problem with the CSUs in an article entitled “Trojan Horse”*:

“The DH has a problem. By 2016 CSUs have to be off the NHS’s books as their grace period as chaperoned NHSE organisations comes to an end. They could be taken over and run by their staff, as a social enterprise or the private sector encouraged to buy-in. The usual suspects, Capita, Serco, Atos, and McKinsey are having a look. KPMG are not. …

Will they make money? Not now, not next year, but assuming there is no political upheaval in 2015, CSUs, as a long term punt, with payback measured in years not months might make them Primary Care’s Trojan Horse.” (Roy Lilley)

On 3 November 2013, the Financial Times had reported the following*:

“The NHS has approached private equity companies about taking over organisations that help buy billions of pounds of services for hospitals and GPs. The talks focus on the 19 commissioning support units (CSUs) set up last year to provide services to the new doctor-led commissioning groups that spend more than two-thirds of the NHS budget. …

CSUs were created as part of contentious healthcare reforms pushed through by the coalition government last year in the teeth of fierce opposition from Labour and much of the medical profession. Although the turnover of the 19 units range from just £21m to £62m a year, together they employ nearly 9,000 staff, designing health services and providing back office IT, procurement and payroll services to clinical commissioning groups. While the CSUs are subsidised by the NHS, they are expected to become self-sufficient profitmaking businesses or form joint ventures with the public or private sectors by 2016.” (Financial Times)

The public’s lack of appetite for privatisation

The public generally think that all privatisations work with a lot of publicity like the BT or Royal Mail one. Where ‘word-of-mouth advertising’ has usually effective (e.g. “Tell Sid”), campaigns anti-NHS privatisation can all too easily go viral (pooled efforts of NHS activists on the section 75 regulations, which saw withdrawal of the original statutory instrument.)

The situation of the ongoing NHS privatisation, across a number of successive UK administrations, is fundamentally different, as in this case the whole project can only work if the public do not realise that they are being duped. Many organisations, politicians, and other leaders can rightly share the blame for not been truthful about the situation. What in fact is most incredible that the process of privatisation of the NHS has been so vehemently denied by politicians and think-tanks, when it is all so incredibly blatant.

There are still a few ‘barriers’ to the ultimate end described below, but these are not impossible for the ‘privateers’ given the right environment.

These include the election of a government which can implement the final steps (this could be any of the main political parties based on their past performance), a NHS IT system ‘fit for purpose’, a method of allocating funds for CCGs depending on individuals’ contributions, a method for allowing top-up payments, to name but a few. However the privateers will be encouraged by the privatisation ‘progress’ which has been made in the last few years.

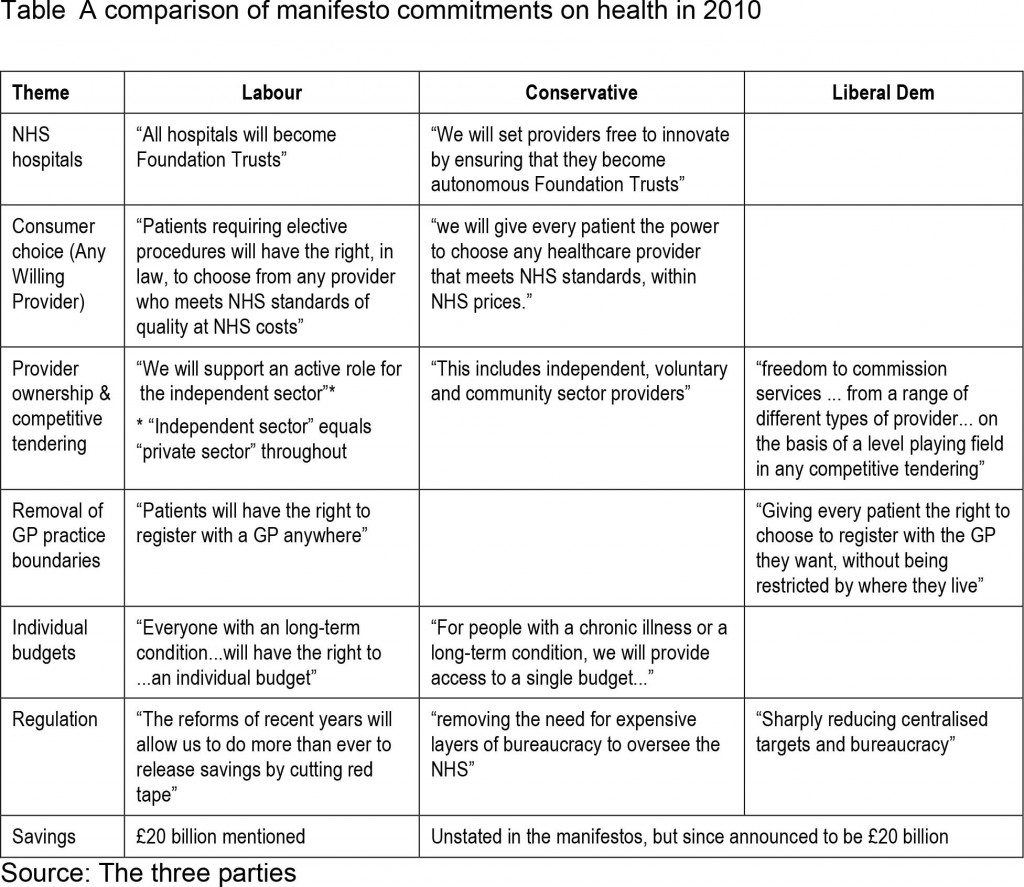

Appetite for privatisation had failed to increase prior to the last election, despite little manoeuvres like the NHS logo available to private companies to make it hard for patients to distinguish between services provided by them and the NHS proper; and permitting private hospitals to compete to sell whichever procedures they wish to offer. With all three main major political parties having converged on the market, there was barely a cigarette paper’s difference between these parties from which to choose.

Arguably, however, it would be quite unfair to blame unilaterally the UK Labour Party with the benefit of hindsight. Labour remain adamant that they would never have enacted a statutory instrument such as the Health and Social Care Act (2012). There is no indication that Labour had intended to publish a similar Act from Hansard. Furthermore, they did consistently fight tooth-and-nail against the Act in the lower House and the House of Lords.

Clinical-based commissioning

Doctors have been sold a bit of a pup, but the media and politicians were adamant that GPs would have a greater rôle in commissioning.

A starting point for understanding the relevance of commissioning to the privatised NHS is the famous Adam Smith Institute’s Pirie and Butler document, which includes a description of their proposed final phase of a switch from a classic NHS to a US-style system. Madsen Pirie and Eamonn Butler are the well known free market gurus at the Adam-Smith Institute. Their entire document reads like a promotion glossy for privatisation, completely bereft of evidence-based academic references.

The end point is a US-style health maintenance organisation (HMO).

The problem of starting new system such as Health Maintenance Organisations is largely avoided by keeping patients with their present GP. In theory, the resources go to the CCG selected by the doctor, although the ultimate choice lies with the patient, who can change CCG by going to a doctor registered with another one. The resources are thus supposed to be directed to the CCGs which are most favoured by doctors and patients.

Nonetheless, it is the CCG who holds the power. As such, CCGs don’t need to have any medical expertise.

Even a Tory MP, Dr Sarah Wollaston, has drawn attention* to how CCGs appear to have gone ‘gun-ho‘ in privatising when David Bennett from Monitor had not felt such a need:

“The existing guidance is widely ignored. David Bennet (sic), the Chief Executive of the regulator Monitor, has set out in a number of settings that commissioners are putting too many services out to tender and yet the waste of resources continues. Perhaps because no commissioners have the spare cash to fight a legal challenge themselves.” (Dr Sarah Wollaston’s blog)

That is why this from Earl Howe is pure ‘smoke and mirrors’ from when the section 75 Regulations were being discussed (shared by Clive Peedell of the National Health Action Party):

Resource allocation and “vouchers”

There are various accounts of how resource allocation works in the NHS, and indeed one of the challenges of understanding NHS privatisation is understanding new parts of the puzzle as they fall into place. NHS England, as Baumann offered in his Health Select Committee evidence this week, will be describing yet another configuration of this formula in December which is apparently going to factor in inequality as well.

In this model, each individual would receive from the state a health voucher, equivalent in value to what he or she approximately is currently ‘consuming’. Making the maths work is of course made a lot easier if the allotted budgets have already been worked out through implementation of ‘personal health budgets‘.

The voucher can be used towards the purchase of private health insurance or exchanged for treatment within the public sector health system. This can easily be sold on the basis of ‘equity’ – that each person has equal access to a ‘National Health Service’ – whereas people actually have access to an inter-tradeable insurance scheme.

Those who opt into private insurance can use the voucher to pay their premiums, and the insurance companies then collect the cash value of the “voucher” from the government. This is the most odd aspect of the model, but easy if you understand the apparent ease with which successive Conservative governments have effectively provided state benefits for their private sector colleagues (see recent outsourcing debacles across a number of sectors.)

The issue of co-payments had been kicked into the long grass.

Sir David Nicholson gave a further reassurance recently (irony klaxon) that it was unlikely that such payments would be introduced imminently on a BBC Radio 4 discussion programme called “Costing the NHS“.

People who decide that health care is particularly important to them are free to add to the amount covered by the voucher and thus purchase more expensive forms of insurance, perhaps covering more unlikely risks or providing superior standards of comfort or convenience.

This is where the right-wing are able to allow for the fact that people who want to pay more can. People on the centre and left, however, interpret this as producing potentially a ‘two tier system’. It is currently not that difficult to find stories of how inadequate the US Medicaid services are currently, and it is a national disgrace of theirs that there are some citizens who are too poor or too ill to be able to afford an insurance-based healthcare.

The voucher would not force people into private insurance, although it certainly makes the option of going private instantly available to everyone. Those who want to use the state service will continue to receive it, their voucher being their ticket to free treatment just as their national insurance number is at the moment.

The distinction between a public health service which does what it can on a take-it-or-leave-it basis, and a private system for the rich which offers choice and competition begins to overlap.

The demise of the CCGs

“Integration” is the standard weapon in the war of words which tries to legitimise the smuggling of the US health insurance industry into running the NHS. The insurance/voucher system fits snugly into such “integration” (or even “whole person care”), and could see one arm of the system (e.g. “universal credit”) enmeshing with another (e.g. “personal health budgets”) for whole person care. This is of course is hugely dangerous without the proper safeguards. Successsive governments have tried so hard to shore up the NHS IT system, under various pretences such as “the paperless NHS”, precisely for this purpose.

A possible relationship between universal credit and whole person credit was mooted here in the mysteriously insightful article by Jennie Macklin and Liam Byrne.

Why are MasterCard so keen on working on payment mechanisms? This article explores possibly why.

The public sector CCGs, taking responsibility for total health care of NHS patients, are not too far removed in structure from private insurance and management bodies. The funds for premiums are publicly provided, but the same competition and incentives operate, and the same choices are made available. Experience, however, from the US is that it is difficult for a patient to sue a CCG directly if a problem arises.

So the Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) still remains a favourite means of achieving the NHS privatisation ‘end game’. The CCG format simply lays the groundwork and the basis for further changes at a later stage.

One of the first things to happen is that CCGs receive their population-based allowances. Whilst it is likely that this will be done on an incremental basis from what the current allocations might be, as CCGs become more sophisticated, they might make use of other techniques such as ‘the dementia prevalence calculator‘ which appears to have achieved somewhat of a pedestal status in dementia public health.

Another trick in the ‘registration process’ is hoping that some members of the public never register and so never receive their allowance. This is known to be a trick of the Department of Work and Pensions which have often failed to notify benefit claimants that their welfare benefits have come to an end.

CCGs might become themselves sitting ducks for becoming insolvent.

The Department of Health will have to conjure up increasingly imaginative methods of arranging CCG funding sharing so as to not make them look like cuts (and find a mouthpiece to publicise them).

A final change of direction for the NHS hoped by some?

Nick Seddon has recently been reported to have caused some controversy by proposing NHS cuts and GP charges. He of course has been the Deputy Director of the think-tank Reform. In 2008, published during the time of a Labour government, Reform produced a pamphlet entitled, “Making the NHS the best insurance policy in the world “.

Their “top recommendations” included the following*:

“These incentives could be introduced by changing the National Health Service to a National Health Protection System. Taxpayer funding and guaranteed access would continue, but individuals would be empowered to decide which approved Health Protection Provider to use. Custody of individual health outcomes would be made independent; it would no longer be in the hands of politicians.

This would mean the following for individuals:

- A “healthcare protection premium” of £2,000 per year would be paid out of general taxation, equivalent to the current NHS cost per individual in England. NB this is similar to the cost of health insurance in France and the Netherlands.

- A choice of where to spend the health protection premium, between Health Protection Providers (HPPs). Coverage for a wide, core level of health treatment, including all essential operations and treatments.

- Extra services, such as gym membership, and rebates for healthy living, for example smoking cessation, offered by HPPs to attract customers.

- Regulation of HPPs by government to ensure they reach minimum standards.

- The ability to top-up their premium to have extra services such as certain drugs, cosmetic surgery or better accommodation in hospitals. People in the UK already value their healthcare enough to spend £1,600 per family per year on health and fitness.The current Departmental review of top-up payments for cancer drugs and the draft EU Directive on cross-border healthcare are likely to lead to greater clarity over what individuals are entitled to and to a new market in insurance for top-up payments.

- Guaranteed accident and emergency cover through a general agreement with insurers, on the model of the Dutch compulsory insurance system.

Because of the positive developments in the UK, this is a task of evolution rather than revolution which could be complete in three to five years. The key steps would be turning Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) into Health Protection Providers; allowing other insurers to join the system; and defining the core entitlement to healthcare.

In January 2008 the Prime Minister described the NHS as “the best insurance policy in the world”. That is the right idea. It means radical change, to combine universal coverage with the focus on the patient evident in other countries. Success would see the UK rejoin the top rank of international health systems and become again the envy of the world.” (Reform Report, 2008)

I remember when I was once in a cab in London, and the cabbie was telling me how, for some private care his wife had received, the insurer had refused to pay for certain aspects of after-care. This is somewhat reminiscent for me of the following criticism made by Reynolds and McKee (2012) in relation to the Reform report*:

“This plan is alluded to in the 2010 white paper in the opaque phrase ‘money will follow the patient’. This refers to the impending roll-out of personal health budgets for all those registered with the NHS. These have been greeted with enthusiasm by patient groups, somewhat strangely when one considers that the NHS currently undertakes to cover all costs of care, whereas the concept of a finite budget implies that it is possible that the actual costs of care could exceed that budget, leaving the patient to cover the excess.” (Reynolds and McKee, 2012)

Andy Burnham MP: “I admit it – we let the market in too far”

Andy Burnham MP is reported on June 9th 2013 as saying the following*:

“When Shadow health lead Andy Burnham MP visited Lewisham the previous evening, he began his speech:

“I admit it – we let the market in too far and now on the 65th anniversary of the NHS we need to renew our commitment to Bevan’s NHS: public service over privatisation; collaboration over competition and people’s wellbeing before self-interested profit.”” (“Left Foot Forward” blog)

This was an important statement to have made.

And Burnham is reported in the same article as wishing to put a stop to the neoliberal firestorm of hospital reconfigurations:

“Later in the day Burnham left his Lewisham audience in no doubt as to his feelings and his intention :

“I give my full support and backing to Lewisham Hospital. 25,000 people marching through the streets is a remarkable achievement. We support the campaign.””

Conclusion

It’s all fairly predictable.

Or so it might appear. You could mount an argument that the present system is far better (having “liberalised” the NHS with non-NHS providers) than having an insurance-based system.

Indeed, indeed Andrew Lansley, the former Secretary of State for Health preceding Jeremy Hunt in the current government, claimed to be opposed to be against such a method of funding the NHS when the Bill was beginning to reach a climax in its discussions.

(see beginning of this video)

Aside from who exactly is in the market post 2015, whether it’s Andy Burnham MP’s “NHS preferred provider” or the Coalition’s “Any qualified provider”, it’s still of concern that there’s still a market. As a first step, Burnham in October 2012 asked for a block on the further ‘roll out’ of “any qualified provider”.

There’s no ‘conspiracy theory’ about it.

For anyone with a training in business and commercial or corporate law, it’s dead obvious.

If you wish to look at what we might be heading to, this overview of the ‘current problems’ of the US healthcare system is a good introduction.

‘Competition’ was used to crowbar the market in. Everyone knows that. People who aggressively pimped competition as a means of improving quality know exactly how faulty their reasoning was (see my previous blogpost). Unfortunately this has done massive damage to English health policy.

This video’s quite useful as it approaches some topics which will are likely to become inevitable for us in this jurisdiction, if we should decide to go down this route: what the process of transformation will cost, how the insurance packages are likely to have to be controlled, competition between CSUs and competition between CCGs in the private market (we know quite how successful competition has been in the energy market), what clinical services will still become out-of-scope, and so on.

The current ‘state of play’ is that Labour has stated categorically to repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012) on many occasions. This is a determined attempt to ‘turn back the tide’ on NHS privatisation, which is a highly popular move amongst potential Labour voters.

Specifically, Labour wishes to put the stuff on competition in part 3 of the Act into reverse. Both Andy Burnham MP and Ed Miliband MP have stated their intention for this independently. Andy Burnham MP is reported as recently as 25 September 2013 as emphasising that he will end ‘fast track privatisation’.

A shift in emphasis from competition to collaboration will make it difficult to run the NHS as a market based on the rules of EU competition, with the correct adjustments in legislation from the Executive.

Many brilliant NHS activists have had landmark successes in opposing Government policy, too.

Never have the stakes been higher for the NHS with the election of the next UK Government, to take place during the course of May 8th 2015.

Try to talk to someone else about it to see what they think?

Why George Osborne's parking spot is such a problem

George Osborne wished to approach this week, Master Tactician that he is, setting the news agenda away from ‘The Millionaire’s Tax Cut’, for a debate about welfare reform. However, George Osborne is stuck in a mental rut, as well as perhaps “gutter politics” as proposed by Ed Balls MP, that the welfare reform debate is about shirkers v strivers, not about the pensions of the elderly which in fact constitute the bulk of the budget currently. Osborne in Torytown Toryshire earlier this week used the same image of shirkers being in bed with their curtains closed (with some of the words interchanged) while strivers go to work in the morning. Osborne therefore fundamentally wants to articulate his welfare debate in the language of ‘fairness’. He doesn’t wish to talk about those Directors of HBOS which have been alleged to underperform and who had been holding ludrative positions elsewhere. Not that kind of fairness. He doesn’t particularly wish to talk about tax avoidance – even though he has a “crack squad” of a handful of people looking into the billions which disappear because of multinational tax avoidance. No, instead, Osborne is pathologically stuck in a mental mindset of pointing the finger “at those below you” who earn more by doing less, not “at those above you” who earn more by doing much less.

Enter Mick Philpott. Like Ed Miliband ‘wants to have a conversation with you’, George Osborne wants you to have a debate about shirker psychology. However, Osborne’s fundamental problem is that benefit fraud, even according to the DWPs’ own statistics, is a relatively minor problem compared to other problems in the welfare budget. Also, it is dangerous to construct policy on the basis of one extreme example, for the same reason you would not necessarily reconstruct the entire policy of inheritance tax based on the recent Seddon case. The Daily Mail and George Osborne have undoubtedly succeeded in their primary goal of having people “discuss” this issue; except the discussion is one of competing shrills, of blame and counterblame, and there is a lot of noise compared to a weak signal.

This morning, George Osborne is facing more criticism over welfare reforms after he was photographed getting into a car parked in a disabled space. The picture shows the Chancellor being picked up by his official car in a restricted bay, after he stopped for lunch at the Magor services on the M4 in Monmouthshire. Senior Conservative sources said he had been to buy food from McDonald’s and was not aware the Land Rover had been inappropriately parked. George Osborne’s parking spot, on the front cover of the Daily Mirror, is a problem for a number of reasons. The embarrassing incident comes as the chancellor stands accused of pushing through welfare reforms that will hurt the disabled, including housing benefit cuts for people with spare rooms. The disability charity Scope says 3.7 million people will be affected by the government’s welfare cuts, losing £28.3bn of support by 2018. The charity’s chief executive, Richard Hawkes, told the Mirror the incident “shows how wildly out of touch the chancellor is with disabled people in the UK”. He said: “They will see this as rubbing salt in their wounds.

The issue is that George Osborne’s “team” appears to be taking up a parking space which should be taken up by a “real” disabled citizen. This taps into the “hypocrisy” attack of voters which is a very potent one – and when it is combined with an attack on someone perceived as privileged, there is a lot of political capital in it. This argument is only tenable if it happens that George Osborne’s driver is not disabled; it is perfectly possible for him or her to be a person with an obvious disability or a “hidden” disability. If the criticism of Osborne’s “team” is correct, then the idea of someone claiming something fraudulent is exactly what Osborne has seemed to accuse disabled citizens of. Osborne’s defence is one of ignorance, and indeed it is perfectly possible that his “team” parked in this parking spot negligently or innocently rather than fraudulently. However, it is a fundamental tenet of the English law that ignorance is no defence, in other words “ignorantia non excusat juris”. Nobody is above the law, including George Osborne, even if it is possible for the Coalition to rewrite hurriedly the law if it does not suit their purposes with the help of Labour (such as happened recently with the Workfare vote over which a number of Labour MPs were forced to rebel.)

The starting point is, of course, that George Osborne is inherently unpopular with Labour voters (and some within the Conservative Party say that he is inherently unpopular with many within the Conservative Party as well.) A lot of this is “personality politics”, in part contributed to by Osborne himself who appears to revel in playing a ‘pantomime villain’. He was openly very hostile to Alistair Darling, but since May 2010 when the economy was in fact in a fragile recovery, he has driven the economy at high speed in the reverse gear, and, whether or not the service sector recovers, he has taken the UK economy through a “double dip”.

Of course, the issue is a “storm in a teacup”, compared to NHS management, the management of the economy, etc., and Conservatives will feel that it is ludicrous that Osborne is being harrassed into apologising for a relatively minor incident. It is impossible to locate somebody who has never made a mistake. However, in the political “rough-and-tumble” ‘every little bit helps’, and the incident is not an isolated one contributing to an overall ambience of perceived incompetence. The other famous incident is of course when Osborne claimed that “his team” was unable to upgrade his standard class ticket to First Class, while he was merrily sitting in First Class. After a while these incidents, while perhaps unfortunate, all blend into the “pantomime villain” persona of George Osborne as a man who simply doesn’t care. A man who doesn’t care is normally pretty unattractive to voters, even in “white van” (or “white suit”) Tatton.

Neuroscience and the law: the current insanity of the insanity law in England

While we wait even longer for the English Law Commission to deliberate on the future of the insanity defense, it is worth noting that events have supersed my last blog. Two years ago, a “devoted husband” who said he killed his wife because he thought she was an intruder has been freed by a judge, who told him he bore no responsibility (the news item dated 20 November 2009 is on the BBC website here).

Brian Thomas, 59, admitted killing Christine, 57, in their camper van, but blamed his rare sleep disorder. The judge told the jury to declare Mr Thomas, of Neath, not guilty over the death in Aberporth, Ceredigion in 2008.

The case involved automatism as a cause of ‘insanity’. Automatism is essentially a legal defense, arguing that a person cannot be held responsible for their actions because they had no conscious knowledge of them. It is a legal defense in the sense that the correlates of what is happening in the brain are poorly understood, therefore leaving psychiatrists with some difficulty in providing evidence on it for thecourts.

They drew attention to the fact that the present law derives from a work written in 1797. The current test uses out-of-date language (the accused has to be suffering from ‘a complete alienation of reason’). This terminology cannot be easily understood by persons who have to apply it, such as psychiatric experts or jurors. Clearly, this definition does take into account the rapid advances in cognitive neuroscience, nor in legal academia about the nature of responsibility.

The Scottish Law Commission further argued that the reformed defense should require the presence of a mental disorder suffered by the accused at the time of the alleged offence. The existence (or non-existence) of a mental disorder in a particular case would normally be a matter for expert, psychiatric evidence. The core element of the defense should be that, by reason of a mental disorder at the relevant time, the accused was unable to appreciate the nature or wrongfulness of his or her conduct. Now the hard part! What would the defendant or his lawyer need to prove that this was the case at the time?

The problem is obviously the defendant can be made subject to all sorts of complicated tests. For example, it is known that many legal diagnoses of insanity actually correspond to a diagnosis of psychosis or schizophrenia. However, for such patients, an electroencephalogram or MRI (advanced brain scan) can be normal. And what about proving that the defendant suffers from some abnormality in moral thinking? The group led by Josh Greene at Harvard has only just begun to develop such tests, and to find out how the brain processes moral behaviour. Or could it be a problem with impulse control? Or could it be that the defendant simply has no idea about his own mental state, what the neuropsychiatrists called “anosognosia”?

The upshot is that the law is ripe for reform. People, however, disagree how. One valid view is that the defense of insanity should be simply abolished. Abolition of the defense has been considered in academic literature for some time. Furthermore as a reaction to the Hinckley case in 1982 some states in the USA enacted measures to abolish the insanity defense.

There is now the added issue of how the English law can be reconciled with European law. Article 5(1) of the European Convention of Human Rights provides for a general right to liberty and security of a person and states that no one “shall be deprived of his liberty save in the following cases and in accordance with a procedure prescribed by law.” One of the specified cases is in paragraph (e) of that article which provides for “the lawful detention of persons for the prevention of the spreading of infectious diseases, of persons of unsound mind, alcoholics or drug addicts or vagrant.”

A fascinating legal journey has now begun, and at present the destination is unclear. Watch this space!

@legalaware has a Ph.D. in cognitive neuropsychology from the University of Cambridge and a LL.M. in international legal practice from the College of Law. The events reported here are true to the best of the knowledge of the author, according to published reports currently available.

Where now for a law of privacy in England and Wales?

The row over court privacy rulings has come to a head in the past few days – as politicians used parliamentary privilege to name Ryan Giggs as the footballer at the centre of one injunction, and to reveal details of another injunction concerning former RBS boss Sir Fred Goodwin. However, the High Court has rejected attempts to overturn the injunction concerning Ryan Giggs – despite his name being published following MP John Hemming’s intervention in Parliament.

David Cameron has said privacy rulings affecting newspapers were “unsustainable” and unfair on the press and the law had to “catch up with how people consume media today” . He has apparently written to Mr Whittingdale and the chairman of the justice select committee, Lib Dem MP Sir Alan Beith, to ask them to suggest members for a new joint committee of MPs and peers, to consider the issue more carefully.

There are currently at least four possible “ways forward” for the new law of privacy which has been developed by the courts over the past decade and which has, at least from the point of view of sections of the media, been very controversial. These are as follows.

(1) Active steps could be taken to abolish the law of privacy and return to the pre-Human Rights Act position.

(2) The current “judge made” law of privacy could be replaced by a new “statutory tort” of invasion of privacy.

(3) A special “privacy regime” for the media could be established under a statutory regulator.

(4) “Primum non nocere” – the law of privacy could be left to develop in the current way – by the judges on the basis of the Article 8 and Article 10 case law.

Each of these possibilities gives rise to different issues and potential difficulties.

Abolition of the Law of Privacy

The law of privacy has been developed by the judges as part of the common law and the common law can be replaced by statute. The new law of privacy has been developed as a result of duty placed on the courts to act compatibly with convention rights imposed by section 6 of the Human Rights Act However, these steps would, in turn, risk placing the United Kingdom in breach of its positive obligations under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights to protect privacy against media intrusion. This would, in turn, lead to adverse findings in Strasbourg and place the United Kingdom under an obligation in international law to re-introduce a law of privacy. In order to escape from this obligation it might be necessary to denounce the Convention and withdraw from the Council of Europe. As adherence to the Convention is a condition of EU membership it would also be necessary to leave the EU. of the law of privacy is not practical.

A Statutory Tort

The second possibility is the introduction of a statutory tort – a course favoured by a number of official inquiries bodies in the 1990s and the early 2000s – presents no such practical difficulties. The advantages of a new statutory tort are that it would enable clearer boundaries to be defined (although some flexibility would, of course, have to be retained). It would also give the privacy law the democratic legitimacy which the new judge made law of privacy is said to lack. This approach has been taken in a number of different common law jurisdictions. Statutory torts of privacy have been introduced in four provinces of Canada.

The Australian Law Commission has recommended the introduction of a statutory cause of action for a serious invasion of privacy containing a non-exhaustive list of the types of invasion which fall within the cause of action. It was suggested that in order to establish liability a claim would have to show:

(a) A reasonable expectation of privacy; and

(b) The act or conduct complained of is highly offensive to a reasonable person of ordinary sensibilities (See Australian Law Reform Commission, Report 108, May 2008, Recommendations 74-1 and 74-2, p.2584).

The Hong Kong Law Reform Commission proposed the introduction of a tort of invasion of privacy in the following terms:

“any person who, without justification, intrudes upon the solitude or seclusion of another or into his private affairs or concerns in circumstances where the latter has a reasonable expectation of privacy should be liable under the law of tort if the intrusion is seriously offensive or objectionable to a reasonable person.” (HKLRC Report, Civil Liability for Invasion of Privacy, 9 December 2004).

A statutory tort of this form would be unlikely to cause difficulties with Article 8 and the Convention. The United Kingdom’s positive obligation would be discharged by its introduction. The Article 8 rights of private parties would be protected by means of civil claims under this tort.

It is envisaged that the introduction of such a law would improve the ‘rule of law’, by enhancing access to justice. Currently, it is said that the present furore over superinjunctions is one in the eye for some London firms of celebrity lawyers, who have made large sums out of their new tools of “reputation management”. As a pioneer of privacy injunctions – Schillings obtained a trendsetting order in 2004 for model Naomi Campbell – the firm has not been short of new clients or referrals from media advisers. It insists it acts only on clients’ instructions and even after John Terry’s injunction was overturned last year, the firm suffered no decline in celebrities seeking gagging orders. In both the Giggs and Trafigura cases, the injunctions were destroyed by a combination of old and new forces. British politicians using the ancient powers of parliamentary privilege, combined with thousands of tweeters, often sitting at foreign-based computers and invulnerable to orders of British judges.

A Statutory Regulator

The third option – the establishment of a statutory regulator – is potentially the most radical. Such a regulator could take a wide variety of forms. The most cautious would simply be to replace the PCC with a statutory body – “OFPRESS” – performing functions similar to those performed by OFCOM in relation to the broadcast media. This may or may not command greater public confidence but would not, of itself, affect the application of the new law of privacy to the press.

Primum non nocere

The most straightforward approach is, of course, do nothing. In other words, let the judges continue the development of the law of privacy on the basis of Articles 8 and 10. This course has the advantage of requiring no Parliamentary time or difficult drafting. It is nevertheless unsatisfactory because it means that the issues arising will not be the subject of proper public debate.

As Carl Gardner notes on his blog (http://www.headoflegal.com/),

“There’s nothing wrong with the privacy law Parliament enacted in the Human Rights Act 1998, and which the judges are loyally applying – except that redtop newspapers want to breach and destroy it in their own commercial interests, and that many internet users have allowed themselves to be persuaded to flout it by a one-sided, self-serving and ill-informed media onslaught. I find it astonishing that, against the background of the News of The World phone hacking scandal, so many people swallow the claim that it’s judges who are out of control. As Alastair Campbell has implied in what he’s tweeted, what’s happened today is no victory for free speech, but for the worst of British journalism.”