Home » Posts tagged 'policy'

Tag Archives: policy

Time for a new regeneration. The New Secretary of State for Dementia.

Ed Miliband looks a bit awkward eating a bacon sarnie, or simply looks a bit “weird”. This man doesn’t look like your next Prime Minister?

But switch back into the reality. A cosmetic reshuffle where the present Coalition had to ditch a Secretary of State more toxic than nuclear waste from Sellafield to transport in a catwalk of tokenistic young hopefuls, “governing for a modern Britain”.

And engage a bit with my reality: where English law centres have been decimated, nobody is feeling particularly “better off” due to the cost of living crisis, GPs have been pilloried for being “coasters”, criminal barristers have gone on strike, or you can’t get your passport on time.

Whisper it quietly, and nobody wants to admit it, that despite all the concerns that Labour will front another set of middle-class neoliberal policies, Labour is in fact going to walk it on May 8th 2015 as the new UK government.

This will obviously be quite a shock to the system, and you can already feel the Civil Service behind the scenes mentally preparing themselves for a change in flavour for the dementia policy.

The current dementia policy had “Nudge” fingerprints all over it. “Customer facing” corporates could become dementia friendly so as to allow market forces to gain competitive advantage for being ‘friendly’ to customers living with dementia.

The Alzheimer’s Society got thrust into the limelight with the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge, ably supported by Alzheimer Research UK, to offer the perfect package for raising awareness about dementia and offering hope for treatment through basic research. This private-public partnership was set up for optimal rent seeking behaviour, with the pill sugared with the trite and pathetic slogan, “care for today, and cure for tomorrow.”

Except the problem was that they were unable to become critical lobbying organisations against this Government, as social care cuts hit and dementia care went down the pan. Dementia UK hardly got a change to get a look in, and it looked as if a policy of specialist nurses (such as Admiral nurses) would get consigned to history. They are, after all, not mentioned in the most recent All Party Parliamentary Group report on dementia.

It is widely expected that Labour’s NHS policy will be strongly frontloaded with a promise of equality, which the last Labour government only just managed to get to the statute books. Insiders reckon that this policy will be frontloaded with an election pledge with equality as a strong theme.

In the last few years, it has become recognised that caregivers feel totally unsupported, people get taken from pillar to post in a fragmented, disorganised system for dementia with no overall coordinator, and there are vast chasms between the NHS and social care treatment of dementia.

The next Government therefore is well known to be getting ready for ‘whole person care’, and it now seems likely that the new Secretary of State for Health and Care under a new government will have to deliver this under existing structures. This will clearly require local authorities and national organisations to work to nationally acceptable outcomes for health and wellbeing through empowered Health and Wellbeing Boards. This will help to mitigate against the rather piecemeal patchwork for commissioning of dementia where contracts tend to be given out to your friends rather than the quality of work. Health and Wellbeing Boards are best placed to understand wellbeing as an outcome (which can become missed in research strategies of large corporate-like charities which focus on care, cure and prevention).

And the switch in emphasis from aspirational friendly to a legal equality footing is highly significant. The new policy for dementia under the new Secretary of State will be delivering what people living with dementia have long sought: not “extra favours”, but just to be able to given equal chances as others. Environments will have signage as reasonable adjustments for the cognitive disabilities of people living with dementia in the community under the force of law, rather than leaving up to the whim of a corporate to think about with with the guidance of a fundraising-centred charity to implement.

With the end of the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge in March 2015, which has been highly successful in places in delivering ‘dementia friendly communities’, a commitment to improved diagnosis rates and improved research, it is hoped that the next government will be able to take the baton without any problems. It will be quite a public ‘regeneration’ from Hunt to Burnham, but one which many people are looking forward to.

Labour can make political weather on the NHS, but it shouldn’t be thrown off track by gale force winds

Political decisions will always be made, but are unlikely to be representative if certain people don’t wish to be part of the political process.

It is hard to know what has caused a decline in political engagement, but politicians not appearing to listen might be a major factor. The social media has empowered a plurality of opinions, which means that it is less easy for politicians to speak with a collective voice on issues. The traditional narrative is that people ultimately care about the economy, as economic competence is the sort of issue which can make or break political parties. However, it’s very likely that residents of Lewisham care about local hospital closures, and hospital campaigns can gain momentum and traction whatever the state of national politics.

Voices of Labour who are interested in social justice, solidarity, equality, equity, solidarity or cooperation are not in fact in a minority, whatever the current state of the Blairite arm of the political party. While think tanks prioritise concepts such as ‘accountability’ and ‘co-production’, authentic voices on the left do not feel that their brand of politics is irrelevant. The question inevitably arises – if the current party is doing what you want to do, why should you stand for election? It is possibly the case that many people will nonetheless vote for Labour, despite reservations on the ‘welfare cap’, because the modern political system does not offer them any realistic choice. ATOS were contracted to do welfare benefits in the last government, and it is likely that some other outsourcing company will assume the mantle.

Labour clearly will state that it is insufficient for political parties to lose elections for others to win them, and they should formulate coherent policies of their own. But likewise nobody will expect Ed Miliband to reveal his hand until much closer to the election. Many people do not come into contact with the NHS when young, although there are many who do, and it is possible that Labour will wish to hone its offering on general health issues as well as the National Health Service. The recent Clegg v Farage debates have highlighted some appetite for single issue politics, when charismatically explored in ‘leaders debates’.

The forthcoming European elections will give a good indicator as to the relevance of the NHS to people’s lives, arguably. The fate of Louise Irvine and Rufus Hound will possibly provide good clues as to whether people in the general public care as much about the NHS as much as NHS campaigners clearly do. The National Health Action Party – NHAP – to be national will need to have coverage throughout the country, but there has always been concern about whether they might realistically gain enough seats to prevent Labour from winning an overall majority. Nonetheless, this Party feels serious that the NHS is a major political issue, and it is a genuine policy issue what they feel they can achieve over and above what a Labour government might. It is possible that that the NHAP might prevent a Labour MP from being elected in Stafford. I met someone recently who was adamant that, with the right resources, NHAP could win in Stafford. Likewise, it’s possible that Clive Peedell could win against David Cameron in Witney, where arguably Labour do not have a realistic chance of winning.

With the second rabbit to come out of George Osborne’s hat in the form of pension reforms, the first being inheritance tax, it’s possible that Labour can’t take the running of the economy as a vote winner in the 2015 general election. Some people still blame Ed Balls as too intimately implicated in the economic policy of the last administration. It is therefore counterintuitive to imagine then that Labour will wish to ignore its potential strengths such as social justice. Despite the concerns over ISTCs and PFI in previous Labour government, and the events running to Mid Staffs, it is still controversial whether people feel strongly enough about Labour’s record not to vote for them. Even hardened Socialists might be keen to contribute to the election of a Labour government than to see the continuation of a Conservative one.

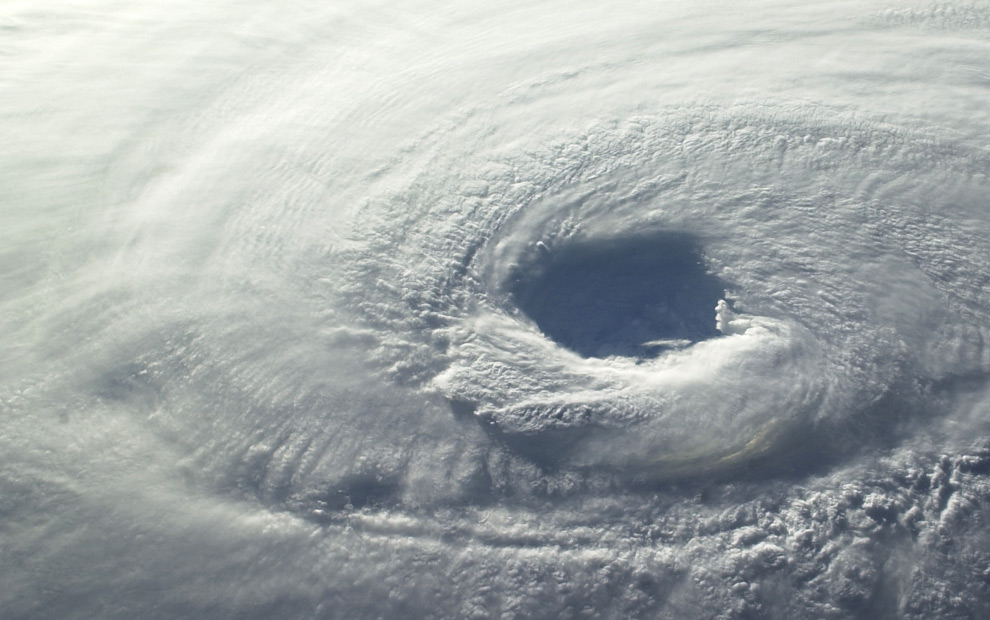

The £2.4 bn top down reorganisation resulting from the Health and Social Care Act (2012) is a major faultline in national policy. Most seasoned pundits are aware of the calamitous effects of competition on national policy, but it is far more likely that members of the general public are unconcerned about ‘section 75′. As sure as night follows day, it’s likely that Labour will oppose privatisation, but the logical conclusion of this is that it supports state ownership. Its inability to call for this publicly speaks volumes. And the people who argue that this country is fundamentally right-wing know they’re being economical with the truth. Unpopular policies from the right have included the astronomic pay of certain investment bankers, the cost of energy bills, the general failures of privatisation policies, perceived attacks on the welfare state, and an enthusiasm to introduce tuition fees in universities denying access-to-education. Whilst Labour is unlikely to voice loudly that ‘capitalism kills’, Labour potentially can make some political weather on the NHS and on health issues such as ‘whole person care’. This will require some strength in the leadership of the Labour Party, but it should not be thrown off course by the equivalent of gale-force winds.

Is the battle of the “Private patient income cap” for non-NHS work actually a battle Labour wishes to win?

One of the first rules in life is that you should be prepared to fight your battles to the hilt, but you should pick the right battles first. The cardinal assumption of Labour’s policy is that it embraces the market. From this, everything in the Health and Social Care Act (2012) has flowed, including awarding procurement contracts to the private sector through competitive tendering, insolvency regimes of ‘failing’ hospitals, and the need for an economic regulator with teeth.

Ed Miliband has made it clear in his ‘One Nation Economy‘ that he doesn’t wish to see the private sector at war with the public sector or vice-versa. To this end, he appears aspire to a promised land where unionised workforces are relevant also to the private sector, enforcing decent working conditions for employees, perhaps through a ‘living wage‘. This obviously has consequences for the ‘One Nation Society‘. Despite Miliband having fired some shots at overzealous corporates, he has previously emphasised the need for corporates to act like good citizens, like members of Unions, with no ‘vested interests‘. This of course is the ‘One Nation political process‘.

The NHS is an important institution for Labour, and Labour is consistently a number of % points ahead of the Conservatives on the NHS, despite the rather boombastic hate-filled speeches coming from the Conservative Party. The argument of ‘public good, private bad’ is argued by some to be outdated, whereas others feel that it is more important than ever to ‘fight for the NHS’. Burnham has been quoting Nye Bevan to ‘motivate the troops’, against the backdrop of a £2.4 bn reorganisation which can only lead to a fragmented, privatised NHS.

Nurses, healthcare assistants and doctors form the backbone of the NHS, a vast majority are a member of a Union of some sort, and some of these also want to do private work, it is argued. Labour wishes to propose a narrative where it wishes to protect NHS values, but the history of Labour involving the private sector is not new, with the private finance initiatives, independent sector treatment centres, and “NHS global”. Drawing on analogies with other sectors, the hospital is not just a place where you get treatment; people go there to improve a sense of wellbeing. Hard-nosed business analysts might argue that this is not a million miles away from a top-notch cinema, where most of the money is not made from displaying the film but selling the popcorn.

It is difficult to argue against the idea that the NHS itself shows great diversity at secondary care level. For example, there are district general hospitals in the community, NHS Foundation Trusts, and “tertiary referral” centres where difficult cases from NHS Foundation Trusts (or cases from abroad) might become referred. They will all have medical Doctors doing varying degrees of acute versus chronic work, and practice-oriented work compared to academic research-oriented work, for example. It can be argued that certain tertiary unit hospitals, such as Great Ormond Street, Moorfields Eye Hospital, the Royal Marsden, or the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, see complicated cases with a unique capacity for research and innovation, which is even hard to compete with on the global stage. It is hard to describe that the case mix of the Royal Marsden for cancer and palliative care on the Fulham Road is the same as a busy unit such as Northwick Park on the Harrow Road in Middlesex.

There are various assumptions about the ‘exporting’ of care too. There has been a focus on US companies wishing to muscle in on the National Health Service, enabled perhaps through the US-EU Free Trade Treaty, but it is an escapable fact that there are many laboratories and medical firms of great expertise here in the UK, particularly in Cambridge and London, which provide really ground-breaking expertise in novel therapies and orphan drugs that can easily be exported. At the other end of this luxury end of the market is the value end, where high volume of very basic diagnostics can be done as a service theoretically for anyone in the world.

The current situation regarding the “private patient income cap” (more correctly an “income cap for non-NHS work“) in the Health and Social Care Act, through s. 164(1)(2A), is described as follows:

An NHS foundation trust does not fulfil its principal purpose unless, in each financial year, its total income from the provision of goods and services for the purposes of the health service in England is greater than its total income from the provision of goods and services for any other purposes.

This figure, that the patient income from non-NHS sources must not be above 49% effectively, is nowhere near the ‘cap’ in previous incarnations of the law in this jurisdiction, and indeed many Foundation Trusts do not have a figure anywhere like 50% of private income. This has been interpreted as a “cap”, and provides an emotional campaigning tool regarding the NHS ‘going into private hands’, but has been there in some forms for several years. The problem with the notion of a “cap” is that it all too easily can be interpreted as a target, where hospitals try to ‘compete’ for which can generate the most income from non-NHS sources, and don’t wish to be ‘the odd one out’. A parallel with this might be how Universities have, between themselves, set the level of their tuition fees. The cap itself seems arbitrarily selected, in that conceivably there could be no cap at all. The actual purpose of the cap might be symbolic, in signifying that NHS hospitals cannot under law allocate all their resources into doing non-NHS work.

Mark Britnell at KPMG has previously given two possible justifications for allowing NHS Foundation Trusts to generate non-NHS income: that is, so that the income can be pumped back into the NHS to improve facilities and to encourage innovation.

The problem with the argument proposing a subsidiary source of funding, it can be led to the conclusion that those hospitals which do not have a private source of income produce worse patient care than those who do. This is a very powerful, and dangerous, signal.

Without a guarantee that there is a minimum spend on NHS care (for example on staffing), it is possible that money might get siphoned off into the private sector, and ‘private patients’ on NHS sites might be ‘queue jumping’ and ‘competing’ for the time of NHS doctors and nurses on site.

On the other hand, it might be good for the patient that skilled NHS doctors are also available on site to deal with complex problems of private patients, as they are all competent in acute medicine, and it also allows NHS doctors to work for NHS institutions rather than to work entirely for the public sector.

The first offering through this improved patient care argument is that this is addressing ‘patient choice’, in other words if patients want private-sector clinical care on a NHS site they should be allowed that opportunity. This might be akin to allowing schoolchildren the opportunity to attend a ‘free school’ in the education system. The second offering is that ‘best practice’ innovation can filter down into all areas of an organisation, and there is an assumption that increased innovation can improve more effective care for patients.

The main problem with this argument is that there can be subtle barriers in transfer of knowledge and innovation within any NHS organisation. These barriers, indeed, are likely to be exacerbated, if there are physical barriers between NHS and private patients in any ‘NHS hospital’, for example they are on different wards.

Andy Burnham and Labour, when they hopefully come into government on May 8th 2015, will have to prioritise what they actually want to do in reality for the NHS. It is likely that, if he can capture the “anti-privatisation” mood music of the country, he will be in government at all. Of course, if Labour remains in opposition, all of this is irrelevant.

A battle which Burnham can presumably attempt to win is for the Secretary of State to offer a universal, comprehensive, free-at-the-point-of-need service in the NHS. If Burnham had really wanted to do this, some say, he would have ‘signed up’ to Lord Owen’s ‘amended duties and powers Bill’ in the House of Lords. As it happens, Ed Miliband has signed up to it, albeit in a Daily Mirror article.

It then becomes a question of priorities. In repealing the Health and Social Care Act (2012), it is all very well for Burnham to champion taming the beast of competition which some might say was unleashed in some form towards the end of the Labour government. Nonetheless, if Burnham champions the ‘NHS Preferred Provider‘, he is still assuming a rôle for the market, and all that necessitates as described in the first paragraph.

It might be unworkable to reduce the cap in a phased manner, or bureaucratically to stipulate that a Trust such as Moorfields goes from 15% to 4% in three years. The management board will have to have some certainty in their business plans, and it is hard not to see this interference as Statist, if it is the case that there has never been any detriment to NHS patient care. Simon Burns MP of the current Government has long argued that there is no actual evidence for any detriment in NHS patient care through uplifting the private income cap.

In aspiring to reduce the cap to ‘single figures’ as Burnham appears to want to do, it could appear that Burnham wishes punitively to fetter the activities of individual NHS Foundation Trusts. Any Trust doing groundbreaking work, such as a novel treatment for macular degeneration in Moorfields Eye Hospital, may find this unnecessary and disproportionate.

There is currently no statutory cap for safe staffing levels, and some might say that this is a more worthy focus of all Governments to improve patient care in the NHS. In striving for consistency in policy, one might wonder why a statutory cap for private income has been imposed nationally, but no definition of safe staffing levels.

On the other hand, the “democratic deficit” may have widened through a £2.4 bn ‘top down reorganisation’, which no-one appears to have voted for. Hunt has often been keen to state that he no longer has direct responsibility for the affairs of individual trusts, and campaigners might feel it is a step too far to see NHS Foundation Trusts ‘doing more private work’.

If NHS Foundation Trusts do more private work, and this is clearly to the detriment of NHS patients, the case for reducing massively the private income cap would be much easier. However, given the diversity of work taking place in the NHS, it can be argued that imposing a statutory cap at all is not an appropriate solution.

Reducing the Private patient income cap is going to be enormously popular with many in the public, but this could turn out to be a battle which Labour may wish it never began to fight.

The writing is back up on the wall: this social democrat neoliberal NHS road to nowhere

The Coalition is the current face of the corporate lobbying over the NHS, but some in Labour have acted as ‘ingluorious basterds‘ too. Ironically, neglect of the NHS was a principal cause of the Conservative government’s downfall back in 1997, and was a major issue that helped New Labour mobilise mass political support for a landslide election victory.

In 2002, Professor Anthony King described the Blair government as the “first ever Labour government to be openly, even ostentatiously pro-business”. Thus, the New Labour leadership had been “converted” from tolerating private enterprise to actively promoting it; a significant political U-turn. Now in 2013, Ed Miliband has recently been in the firing line over a lack of direction or policies, with some Labour members being wheeled out of their holiday villa in Tuscany to emphasise that Miliband will win the election in May 2015. Peter Hain talks in his latest up-beat missive in the Guardian about the New Jerusalem of Labour’s flagship integration policy, which ‘joins up’ health care and psychiatric system, but this is a poor attempt at snakeoil salesmanship from an otherwise very pleasant man. It is indeed emblematic of Labour’s outright denial of the disaster that has been the English health policy over a number of years from senior politicians of all parties. People who do actually want to stand up for a comprehensive, universal, free-at-the-point-of-use, National Health Service are finding themselves struggling to get their message across, while Craig Oliver gets panicky about the media representation of Cameron’s unsightly figure on holiday.

All is not lost. The facts speak for themselves (“res ipsa loquitur“), and Labour cannot escape from its past. Ed Miliband is a ‘social democrat’, but there are plenty in the Labour Party who are senior enough to keep him in check over the NHS. Ed Miliband, despite the loyalists, is on suspended sentence with his conference speech next month in Brighton. Whatever he decides to do about social house building, his inability even to get rid of the Bedroom Tax is a sign that all is not well. Few people currently feel that he is up to the challenge of taking the socialist bull by the horns regarding the NHS policy, not helped by entities such as the Socialist Health Association superbly supine in having no material effect on the real problems that matter to most voters.

And yet all is not lost. Take for example the flagship policy of ‘equal opportunity’, championed by Monitor in lowering barriers-to-entry in a corporate dogfight over who runs the NHS. Tony Blair doesn’t especially mind who runs the NHS, as long as it’s a corporate, as his famous dictum goes. The writing was indeed on the wall as far back as , with the very influential John Denham MP, a former Health Minister, writing in ‘Chartist’ as follows in 2006:

But the Government has adopted a simplistic and ideological formula. All public services have to be based on a diversity of independent providers who compete for business in a market governed by consumer choice. All across Whitehall, any policy option has now to be dressed up as ‘choice’ ‘diversity’ and ‘contestability’. These are the hallmarks of the ‘new model public service’.

We can see this formula behind al the recent major policy rows, and its ideological nature goes some way to explain Labour’s internal opposition. But it’s not the whole reason. Plenty of MPs are willing to look at policy change on its merits, whether or not they have suspicions about its origins. And this is the second point where things go wrong.

However strongly the Government believes in ‘choice, diversity and contestability’ there is little unambiguous evidence in its favour, and plenty of evidence that points to caution. The evidence does not suggest, for example, that choice all leads to inequities but it certainly suggests that it usually does. There are services where a choice of independent autonomous providers may make sense, but the evidence suggests that health, or education, works best when this is cooperation between different parts of the system. The link between your nurse, GP, consultant and therapists is more important than competition between different providers.

John Denham MP still has a massive influence on the Labour Party as is well known, having been instrumental in the selection of Rowenna Davis in Southampton Itchen for the forthcoming General Election on May 8th 2015.

The knives were out with the Labour Grandee, now The Rt Hon The Lord Hattersley, writing in the Guardian on 7 November 2005:

“A couple of weeks ago Tony Blair told a specially invited Downing Street audience that throughout the 80s Labour had been kept out of office because it wanted to “level down”. That allegation is as absurd as it is offensive. But plagiarising Tory abuse is not so serious an offence as adopting Tory policies. Last Friday, he again attempted to make backbench flesh creep with warnings that abandoning his “reform agenda” would lead to defeat. That is not only palpably untrue, it is also not a consideration that keeps him awake at night. His policies are on the right of the political spectrum because that is where his heart is. He has happily admitted it.

Socialism is either the doctrine of public ownership or the gospel of equality. The first Tony Blair (now) rightly rejects. The second he openly wants to replace with a commitment to meritocracy – the survival of the fittest at the expense of the less fortunate and less gifted. That proves his intellectual consistency. No prime minister since the second world war, including Margaret Thatcher, has believed so devoutly in the economic healing powers of the market. Meritocracy is a market in which human beings compete with each other for wealth and esteem. Markets always produce losers as well as winners.

The “choice agenda” requires competition for places in what are called “the best schools” and beds in the most efficient hospitals. Unless there is a surplus of secondary schools with small classes, highly qualified teachers and exemplary results, some parents will be forced to accept what others have rejected. The same rule of winners and losers will apply to hospitals. No genuine Labour leader would allow the self-confident and articulate section of society to elbow the disadvantaged and the dispossessed out of the public service queue.”

The mutant DNA is still to be found in Labour’s current NHS policy, sadly, except these are not lone trace fragments by any stretch of the imagination. We’ve been before though, and Labour has fundamentally been frightened to do the right thing. At the 2005 the Labour Party Conference a resolution was passed that attacked the Government’s move “towards fragmenting the NHS and embedding a marketised system of providing public services with a substantial and growing role for the private sector”. It was left up to Michael Meacher MP to put the writing back up on the wall in an article in March 2007 in Tribune, explaining what Tony Blair should do, if he should win the 2007 General Election:

“Domestically, I would reverse the “new” Labour obsessions of replacing the public service ethos by the market. Equity, equal rights according to need, public accountability, a professional standard of care and integrity are being replaced by targets, cost cutting, PFI top slicing of public expenditure, a service fragmentation by private interests. This is the case of health and education housing, pensions, probation, rail, the Post Office and local government. There are even threats against public service broadcasting. Privatisation of our public services should be stopped and reversed.”

Stuart Hall, Emeritus Professor of Sociology at the Open University, argued that whilst the Labour Government has retained its social democratic commitment to maintaining public services and alleviating poverty, its “dominant logic” was neo-liberal: to spread “the gospel of market fundamentalism”, promote business interests and values and further residualise the welfare system. It now falls to Jon Cruddas in the current policy review to stop the rot in Labour, but his words from his article “How New Labour turned toxic” in the New Statesman on 6 December 2007 ring ever true:

“After years in opposition and with the political and economic dominance of neoliberalism, new Labour essentially raised the white flag and inverted the principle of social democracy. Society was no longer to be master of the market, but its servant. Labour was to offer a more humane version of Thatcherism, in that the state would be actively used to help people survive as individuals in the global economy – but economic interests would always call all the shots. Once the Blair government took power, the essentials of its approach became clear: from the commercialisation of public services to flexible labour markets, on through soaring executive pay and on in turn to party funding, big business and the politics of the market had taken pole position.”

Labour is a leopard which hasn’t changed its spots at all. Hence, apart from Debbie Abrahams virtually, Labour appears to be giving tacit support to a current Government policy which appears to be sympathetic to the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), which aim to opens up service provision like health and education, (which account for approximately 15% of GDP in most European countries) to direct multinational competition and ownership, This, in fact, is despite a statement in 2002 from the UK Government that it would not take on WTO commitments that would compromise public service delivery via the NHS. This represents a major U-turn in healthcare policy and it is therefore important to understand from a historical perspective how and why this happened.

Labour is currently involved in a massive con-trick with the electorate, colluding with the Conservatives and the Neoliberal Democrats, and it won’t be long before real voters spit in their face in response to their claim that, “Labour is the party of the NHS.”

Further reading

Hall S. (2003) New labour’s double shuffle, Soundings.

King A. (2002) ‘Tony Blair’s First Term’ in King A (ed.) (2002) Britain at the Polls.

Avoiding the rollercoaster: a policy for dementia must be responsible

The last few years have seen a much welcome progression, for the better, for dementia policy in England. This has been the result of the previous Government, under which “Living well with dementia: the National Dementia Strategy” was published in 2009, and the current Government, in which the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge in 2012 was introduced.

Dementia is a condition which lends itself to the ‘whole person’, ‘integrated’ approach. It is not an unusual for an individual with dementia to be involved with people from the medical profession, including GPs, neurologists, geriatricians; allied health professionals, including nurses, health care assistants, physiotherapists, speech and language specialists, nutritionists or dieticians, and occupational therapists; and people in other professionals, such as ‘dementia advocates’ and lawyers. I think a lot can be done to help individuals with dementia ‘to live well'; in fact I have just finished a big book on it and you can read drafts of the introduction and conclusion here.

It is critical obviously that clinicians, especially the people likeliest to make the initial provisional diagnosis, should be in the ‘driving seat’, but it is also very important that patients, carers, family members, or other advocates are in that driving seat too. I feel this especially now, given that there is so much information available from people directly involved in with patients (such as @bethyb1886 or @whoseshoes or @dragonmisery) This patient journey is inevitably long, and to call it a ‘rollercoaster ride‘ would be a true understatement. That is why language is remarkably important, and that people with some knowledge of medicine get involved in articulating this debate. Not everyone with power and influence in dementia has a detailed knowledge of it, sadly.

I am very honoured to have my paper on the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia to be included as one of a handful of references in the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine. You can view this chapter, provided you do not use it for commercial gain (!), here.

I should like to direct you to the current draft of a video by Prof Alistair Burns, Chair of Psychiatry at the University of Manchester, who is the current National Clinical Lead for Dementia. You can contact him over any aspects of dementia policy on his Twitter, @ABurns1907. I strongly support Prof Burns, and here is his kind Tweet to me about my work. I agree with Prof Burns that once individuals can be given face-to-face a correct diagnosis of dementia this allows them to plan for the future, and to access appropriate services. The problem obviously comes from how clinicians arrive at that diagnosis.

I am not a clinician, although I studied medicine at Cambridge and did my PhD on dementia there too, but having written a number of reviews, book chapters, original papers, and now a book on dementia, I am deeply involved with the dementia world. I am still invited to international conferences, and I personally do not have any financial vested interests (e.g. funding, I do not work for a charity, hospital, or university, etc.) That is why I hope I can be frank about this. Clinicians will be mindful of the tragedy of telling somebody he or she has dementia or when he or she hasn’t, but needs help for severe anxiety, depression, underactive thyroid, or whatever. But likewise, we are faced with reports of a substantial underdiagnosis of dementia, for which a number of reasons could be postulated. Asking questions such as “How good is your memory?” may be a good basic initial question, but clinicians will be mindful that this test will suffer from poor specificity – there could be a lot of false positives due to other conditions.

At the end of the day, a mechanism such as ‘payment-by-results’ can only work if used responsibly, and does not create an environment for ‘perverse incentives’ where Trusts will be more inclined to claim for people with a ‘label’ of dementia when they actually do not have the condition at all. A double tragedy would be if these individuals had poor access to care which Prof Burns admits is “patchy”. In my own paper, with over 300 citations, on frontal dementia, seven out of eight patients had very good memory, and yet had a reliable diagnosis of early frontal dementia. Prof Burns rightly argues the term ‘timely’ should be used in preference to ‘early’ dementia, but still some influential stakeholders are using the term ‘early’ annoyingly. On the other hand, I wholeheartedly agree that the term ‘timely’ is much more fitting with the “person-centred care” approach, made popular in a widespread way by Tom Kitwood.

I am still really enthused about the substantial progress which has been made in English dementia policy. I enclose Prof Burns’ latest update (draft), and the video I recorded yesterday at my law school, for completion.

Prof Alistair Burns, National Clinical Lead for Dementia

Me (nobody) in reply