Home » Posts tagged 'NHS' (Page 4)

Tag Archives: NHS

“There’s more to a person than the dementia”. Why personhood matters for future dementia policy.

“Dementia Friends” is an initiative from the Alzheimer’s Society and Public Health England. In this series of blogpost, I take an independent look at each of the five core messages of “Dementia Friends” and I try to explain why they are extremely important for raising public awareness of the dementias.

There’s more to a person than the dementia.

In 1992, the late Prof Tom Kitwood founded Bradford Dementia Group, initially a side-line. Its philosophy is based on a “person-centred” approach, quite simply to “treat others in a way you yourself would like to be treated”.

A giant in dementia care and academia, I feel he will never bettered.

His obituary in the Independent newspaper is here.

Personhood is the status of being a person. Its importance transcends medicine, nursing, policy, philosophy, ethics and law even.

Kitwood (1997) claimed that personhood was sacred and unique and that every person had an ethical status and should be treated with deep respect.

A really helpful exploration of this is found here on the @AlzheimerEurope website.

Personhood in dementia is of course at risk of ‘paralyis by analysis’, but the acknowledgement that personhood depends on the interaction of a person with his or her environment is a fundamental one.

Placing that person in the context of his past and present (e.g. education, social circumstances) is fundamental. Without that context, you cannot understand that person’s future.

And how that person interacts with services in the community, e.g. housing associations, is crucial to our understanding of that lived experience of that person.

All this has fundamental implications for health policy in England.

Andy Burnham MP at the NHS Confederation 2014 said that he was concerned that the ‘Better Care Fund’ gives integration of health services a ‘bad name’.

It is of course possible to become focused on the minutiae of service delivery, for example shared electronic patient records and personal health budgets, if one is more concerned about the providers of care.

Ironically, the chief proponents of the catchphrase, “I don’t care who is providing my care” are actually intensely deeply worried about the fact it might NOT be a private health care provider.

Person-centered care is an approach which has been embraced by multi-national corporates too, so it is perhaps not altogether a surprise that Simon Stevens, the current CEO of NHS England, might be sympathetic to the approach.

Whole-person care has seen all sorts of descriptions, including IPPR, the Fabians, and an analysis from Sir John Oldham’s Commission, and “Strategy&“, for example.

The focus of the National Health Service though, in meeting their ‘efficiency savings’, has somewhat drifted into a ‘Now serving number 43′ approach.

When I went to have a blood test in the NHS earlier this week, I thought I had wandered into a delicatessen by accident.

But ‘whole person care’ would represent a fundamental change in direction from a future Government.

Under this construct, social care would become subsumed under the NHS such that health and care could be unified at last. Possibly it paves the way for a National Care Service at some later date too.

But treating a person not a diagnosis is of course extremely important, lying somewhat uneasily with a public approach of treating numbers: for example, a need to increase dementia diagnosis rates, despite the NHS patient’s own consent for such a diagnosis.

I have seen this with my own eyes, as indeed anyone who has been an inpatient in the NHS has. Stripped of identity through the ritualistic wearing of NHS pyjamas, you become known to staff by your bed number rather than your name, or known by your diagnosis. This is clearly not right, despite years of professional training for current NHS staff. This is why the campaigning by Kate Granger (“#hellomynameis”) is so important.

It is still the case that many people’s experiences of when a family relative becomes an inpatient in the National Health Service is a miserable one. I have been – albeit a long time ago – as a medical student on ward rounds in Cambridge where a neurosurgeon will say openly, “He has dementia”, and move onto the next patient.

So the message of @DementiaFriends is a crucial one.

Together with the other four messages, that dementia is caused by a diseases of the brain, it’s possible to live well with dementia, dementia is not just about losing your memory, dementia is not part of normal ageing, the notion that there’s more to a person than the dementia is especially important.

And apart from anything else, many people living with dementia also have other medical conditions.

And apart from anything else, many people living with dementia also have amazing other skills, such as cooking (Kate Swaffer), fishing (Norman McNamara), and encouraging others (see for example Chris Roberts’ great contributions to the community.)

References

Kitwood, T. (1997).Dementia reconsidered: the person comes first. Open University Press.

“Think like a multinational corporate leader. Act like the chief of the NHS.”

Simon Stevens’ catchphrase is: “Think like a patient, act like a taxpayer.”

In 2013, the US and EU decided to start negotiations on a new free trade agreement, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

In a recent piece for the New Statesman, the most notable comments by Andy Burnham MP in George Eaton’s interview concerned TTIP and its implications for the NHS (apart from he was spitting bullets at aspects of HS2).

Many Labour activists and MPs had been concerned, according to George, “at how the deal, officially known as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), could give permanent legal backing to the competition-based regime introduced by the coalition.”

And here was Andy again at the start of the European elections (not reported by the media who were much more interested in Nigel Farage, Roger Helmer, and their ilk.)

As Benedict Cooper wrote recently on The Staggers for the New Statesman:

“A key part of the TTIP is ‘harmonisation’ between EU and US regulation, especially for regulation in the process of being formulated. In Britain, the coalition government’s Health and Social Care Act has been prepared in the same vein – to ‘harmonise’ the UK with the US health system.

“This will open the floodgates for private healthcare providers that have made dizzying levels of profits from healthcare in the United States, while lobbying furiously against any attempts by President Obama to provide free care for people living in poverty. With the help of the Conservative government and soon the EU, these companies will soon be let loose, freed to do the same in Britain …

… The agreement will provide a legal heavy hand to the corporations seeking to grind down the health service. It will act as a transatlantic bridge between the Health and Social Care Act in the UK, which forces the NHS to compete for contracts, and the private companies in the US eager to take it on for their own gain.”

So fast forward a few months.

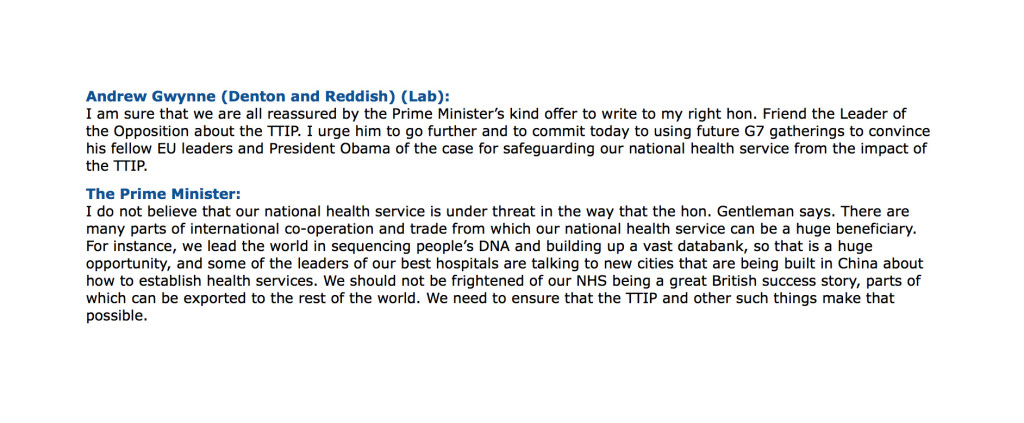

Ed Miliband asked David Cameron today specifically how TTIP would impact on the NHS.

Cameron reported today that there had been five good meetings on progressing it, and continued thus:

“We are pushing very hard and trying to set some deadlines for the work. No specific deadline was agreed, but it was agreed at the G7 that further impetus needed to be given to the talks and, specifically, that domestic politicians needed to answer any specific questions or concerns from non-governmental organisations, or indeed public services, that can sometimes be raised and that do not always, when we look at the detail, bear up to examination.”

And the attack on NGOs continued:

“I do think this is important because all of us in the House feel—I would say instinctively—that free trade agreements will help to boost growth, but we are all going to get a lot of letters from non-governmental organisations and others who have misgivings about particular parts of a free trade agreement. It is really important that we try to address these in detail, and I would rather do that than give an answer across the Dispatch Box.”

So the upshot was Cameron agreed to write to Miliband in detail to provide an update on TTIP and the NHS at last.

And this is not a moment too soon – it’s almost a year to the day since @Debbie_Abrahams asked about this on 19 June 2013 (see here).

Cameron tried also to advance the rather bizarre argument that TTIP would lift people out of poverty, trying to link up in a very Conservative approach to the free trade arrangements and the social determinants of health.

The most helpful exchange, perhaps however, was between Andrew Gwynne and the Prime Minister this afternoon:

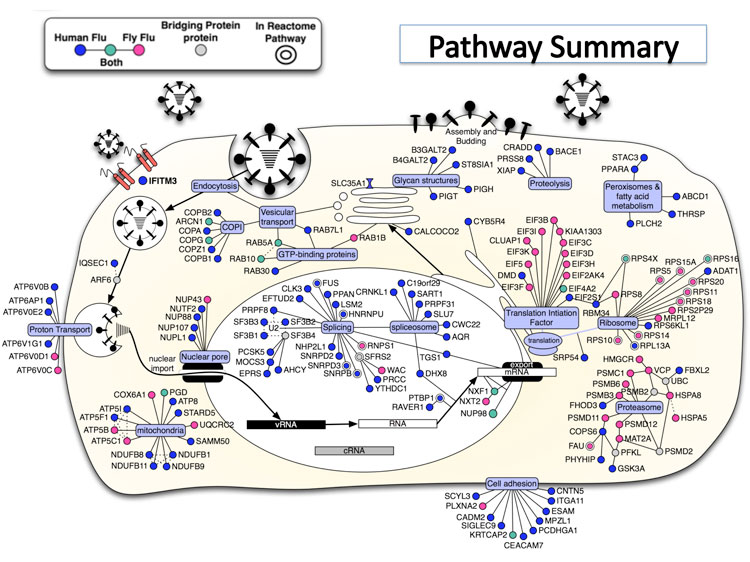

From the late 1980s, a narrative surrounding the ethics and economics of human gene patents has been taking shape into a ‘perfect storm’.

The discussion included impact of gene patents on basic and clinical research, on health care delivery, and on the ability of public health care systems to provide equitable access when faced with costly patented genetic diagnostic tests.

Scientists at institutions around the world discovered and sequenced a series of genes linked to breast and ovarian cancer in the early 1990s.

Mutations in these genes prevent the body from producing tumor suppressing proteins, which in turn increases an individual’s risk of contracting breast or ovarian cancer.

A key discovery, for example, was that individuals with these mutations have a cumulative lifetime risk of ~40–85% of developing breast cancer and ~16–40% chance of developing ovarian cancer, compared with 12.7% and 1.4% risk for the general population of developing breast or ovarian cancer, respectively.

So with these cutting edge findings in research, ‘translationary’ laboratories developed diagnostic tests for these mutations, which opened up the possibility of preventive management for breast and ovarian cancer, including prophylactic surgery and the use of certain medications.

There are countless other examples.

There also has been talk about doing a genomic screen with a view to identifying genetic risk factors for the dementias.

And Simon Stevens lovebombed the idea last week at the NHS Confederation:

“First, personalisation. A decade and a half on from the Human Genome Project, we’re still in the early days of the clinical payoff. But as biology becomes an information science, we’re going to see the wholesale reclassification of disease aetiologies. As we’re discovering with cancer, what we once thought of as a single condition may be dozens of distinct conditions. So common diseases may in fact be extended families of quite rare diseases. That’ll require much greater stratification in individualised diagnosis and treatment. From carpet-bombing to precision targeting. From one-size-fits many, to one-size-fits-one.”

So a more appropriate catchphrase for Simon Stevens might be:

“Think like a multinational corporate leader. Act like the chief of the NHS.”

One concern has been that TTIP powers would jeopardise well entrenched national laws and regulations.

Frances O’Grady of the UK’s Trade Union Congress for example, is publicly concerned that deregulation and bolstering of corporate rights could mean an accelerated privatisation of the UK’s National Health Service.

“The clauses [of ISDS] could thwart attempts by a future government to bring our health service back towards public ownership”.

A “socialist planned economy” combines public ownership and management of the means of production with centralised state planning, and can refer to a broad range of economic systems from the centralised Soviet-style command economy to participatory planning via workplace democracy.

In a centrally-planned economy, decisions regarding the quantity of goods and services to be produced as well as the allocation of output (distribution of goods and services) are planned in advanced by a planning agency.

According to Linda Kaucher, quoted in the New Statesman:

“[The Health and Social Care Act] effectively enforces competitive tendering, and thus privatisation and liberalisation i.e. opening to transnational bidders – a shift to US-style profit-prioritised health provision.”

“The TTIP ensures that the Health and Social Care Act has influence beyond UK borders. It gives the act international legal backing and sets the whole shift to privatisation in stone because once it is made law, it will be irreversible. Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) laws, fundamentals of the agreement, allow corporations legal protection for their profits regardless of patient care performance, with the power to sue any public sector organisation or government that threatens their interest.”

“Once these ISDS tools are in place, lucrative contracts will be underwritten, even where a private provider is failing patients and the CCG wants a contract cancelled. In this case, the provider will be able to sue a CCG for future loss of earnings, thanks to the agreement, causing the loss of vast sums of taxpayer money on legal and administrative costs.”

Given also Andy Burnham’s reported opposition to TTIP, it would be absolutely ludicrous for the Socialist Health Association to adopt any position other than to oppose the parts of TTIP which are clearly to the detriment of the NHS. This situation, I feel, has arisen because “leaders” who’ve never set foot on a ward in a clinical capacity have little understanding of the social capital of its workforce: doctors, nurses, healthcare assistants, and all allied health professionals. It will be painful for members of the Socialist Health Association if they wish to collude knowingly with this non-socialist agenda. This is all the more telling as the Socialist Health Association seem bizarrely silent concerning the pay freeze for much of the nursing workforce.

And so the NHS strategy is beginning to take shape – parallel worlds of grassroots clinical service delivery (the unprofitable bit which costs money), and the more lucrative bit (where the State can use patient data taken from the general public on the basis of presumed con set to develop diagnostic tests and treatments, with the help of investment from venture capitalists and large charities, to export to the rest of the world under free trade agreements).

It is time for the Socialist Health Association to work out who exactly they represent?

TTIP makes intellectual asset stripping look like taking candy from a baby.

And the jury is out on Simon Stevens and the think tanks, many people will also say. But this is possibly a lost cause.

So we wait with baited breath for Ed Miliband’s reaction to David Cameron’s note about TTIP. Hopefully they will not simply agree to this agenda, ever increasing the democratic deficit.

Why are English policy wonks fixated on the dangerous wrong policy of competition for their NHS?

A series of different amendments are coming from various sources to ask Andy Burnham to scrap the market in the NHS.

And indeed Andy Burnham claims to be well aware of the dangers of the introduction of a sort of-market to the NHS:

In recent years, there has been clear unease at policy wonks ‘doing’ the traditional circuits in think tanks, known to feather each other’s nests, with no clinical backgrounds (including no basic qualifications in medicine or nursing), pontificating at others for a cost and price how to run the NHS in England.

Think tanks have been part of the discussion, with blurred lines between marketing and shill and academic research, exasperating the real research community.

The King’s Fund boasts that, “Providing patients with choice about their care has been an explicit goal of the NHS in recent years. Competition is viewed by the government as a way of both providing that choice and giving providers an incentive to improve. The Health and Social Care Act set out Monitor’s role as the sector regulator with a specific role of preventing anti-competitive behaviour in health care.”

Chris Ham, who has previously marvelled voluptuously at the US provider Kaiser Permanente in the British Medical Journal, goes hammer and tong at it on an article on competition here.

The theme or meme comes up as a recurrent bad smell in the impact assessment for the Health and Social Care Bill here, citing in the need to consider equality concerns in competition the reference Gaynor M, Moreno-Serra R, Propper C, (July 2010) Death by Market Power Reform, Competition and Patient Outcomes in the National Health Service. NBER Working Paper No. 16164, July 2010.

The authors of that impact assessment nonetheless reassuringly observe that “Gaynor et al (2010) found competition impacted differently across certain areas with possible negative impacts on transgender and black and minority ethnic (BME) people. However, further evidence implies that these risks, associated with increasing competition, should not be overstated and may not impact upon equality issues.”

Andy Burnham – and Labour – have pledged many times that the repeal of the failed Health and Social Care Act (2012) will be in the first Queen’s Speech of a Labour government.

Policy wonks are human beings, and can fail.

It is well-known that many errors in anesthesiology are human in nature. It’s argued that because equipment failure is an infrequent explanation for mishaps in the hospital, clinicians should be aware of the human factors that can precipitate adverse events.

While there are various types of human errors that can lead to complications, “fixation errors” are relatively common and deserve particular attention. Fixation errors occur when clinicians concentrate exclusively on a single aspect of a case to the detriment of other more important features. This is exactly what has happened with the undue prominence of the benefits of competition in the NHS.

Put simply, without any of the bullshit, competition is simply the crow bar which puts private providers into the NHS.

Milburn and Hewitt have been reading from this narrative from ages, and it threatens to engulf Labour yet again. Burnham is fighting a battle for the soul of the party now, and one can only speculate how successful he will be. He has said on many occasions that collaboration is the key to running the NHS in England, not competition; integration not fragmentation; people before profit.

But if you look beyond the lobbying – you can find the evidence right before your eyes. Jonathon Tomlinson through an excellent blogpost of his refers to a large body of literature from Professor Don Berwick which has been in the literature. This is clearly worth revisiting now.

The New Statesman published last week an article which should make senior healthcare policy wonks in England weep.

Martin Bromiley is neither a doctor, or a health professional of any kind. He is not even a member of the revolving door policy wonks in English healthcare policy. Bromiley is an airline pilot.

“Early on the morning of 29 March 2005, Martin Bromiley kissed his wife goodbye. Along with their two children, Victoria, then six, and Adam, five, he waved as she was wheeled into the operating theatre and she waved back.”

A room full of experts were fixated on intubating her, instead of doing a tracheostomy, which indeed Bromiley indeed asked for. A tracheotomy is a cut to the throat to allow air in.

What happened next was incredible.

“If the severity of Elaine’s condition in those crucial minutes wasn’t registered by the doctors, it was noticed by others in the room. The nurses saw Elaine’s erratic breathing; the blueness of her face; the swings in her blood pressure; the lowness of her oxygen levels and the convulsions of her body. They later said that they had been surprised when the doctors didn’t attempt to gain access to the trachea, but felt unable to broach the subject. Not directly, anyway: one nurse located a tracheotomy set and presented it to the doctors, who didn’t even acknowledge her. Another nurse phoned the intensive-care unit and told them to prepare a bed immediately. When she informed the doctors of her action they looked at her, she said later, as if she was overreacting.”

This is not the first time that a ‘fixation error’ has had disastrous consequences.

Another example happened on 28 December 1978, the United Airlines Flight 173.

A flight simulator instructor Captain allowed his Douglas DC-8 to run out of fuel while investigating a landing gear problem.

It’s a miracle that only ten people were killed after Flight 173 crashed into an area of woodland in Portland; but the crash needn’t have happened at all.

In a crisis, the brain’s perceptual field narrows and shortens. We become seized by a tremendous compulsion to fix on the problem we think we can solve, and quickly lose awareness of almost everything else. It’s an affliction to which even the most skilled and experienced professionals are prone.

In March 2012, Professor Allyson Pollock wrote an article in the Guardian, stating ‘Bad science should not be used to justify NHS shakeup’.

In this article, Pollock argued that pro-competition arguments from economists Julian Le Grand and Zack Cooper at the London School of Economics had produced an incredibly distorting effect on what was an important discussion and, “[raised] serious questions about the independence and academic rigour of research by academics seeking to reassure government of the benefits of market competition in healthcare.”

Pollock argues that such colleagues had been sufficiently successful for David Cameron to declare “Put simply: competition is one way we can make things work better for patients. This isn’t ideological theory. A study published by the London School of Economics found hospitals in areas with more choice had lower death rates.”

It is reported in one case, the previous chief of NHS England, Sir David Nicholson KCB CBE “said a foundation trust chief executive had been told he could not “buddy” with a nearby trust ? under plans announced last week to help struggling providers ? because “it was anti-competitive”.

He continued: “I’ve been somewhere [where] a trust has used competition law to protect themselves from having to stop doing cancer surgery, even though they don’t meet any of the guidelines [for the service].”

“Trusts have said to me they have organised, they have been through a consultation, they were centralising a particular service and have been stopped by competition law. And I’ve heard a federated group of general practices have been stopped from coming together because of the threat of competition law.”

“All of these [proposed changes] make perfect sense from the point of view of quality for patients, yet that is what has happened.”

Meanwhile, there was more product placement for providers including Kaiser Permanente yesterday by Jeremy Hunt in parliament:

“From next year, CCGs will have the ability to co-commission primary care alongside the secondary and community care they already commission. When combined with the joint commissioning of social care through the better care fund, we will have, for the first time in this country, one local organisation responsible for commissioning nearly all care, following best practice seen in other parts of the world, whether Ribera Salud Grupo in Spain, or Kaiser Permanente and Group Health in the US..”

Everyone appears to be fixated apart from the most junior in the room, or people like me who wouldn’t want to touch these jobs in think tanks with a barge pole.

It is indeed a badge of honour for me that the feeling is likely to be mutual.

Competition does not explain whether a person who has had chest pains due to a clogging heart should have a physical stent to open up the pipes of blood in his heart, or whether he needs tablets he can take. That is down to clinical professional acumen.

Competition with few big providers can lead to massive rip offs in prices, because of the way these markets work (these markets are called ‘oligopolies‘).

And all too easily providers can be in a race to the bottom on quality, cutting costs to maximise profits.

Remember Carol Propper’s research being used to bolster up the failed plank of competition in the Health and Social Care Act impact assessment?

Wow.

Here she is again in the speech by Simon Stevens, the new NHS England chief, being used in a slightly new context for his speech before the NHS Confederation last week: of the “sensible use” of competition in the NHS (somewhat reminiscent of the use of the words “sensible use” in the context of another potentially disastrous area of policy – targets):

“If we want to be evidence-informed in our policy making and commissioning lets pay heed to research from Martin Gaynor, Mauro Laudicella and Carol Propper at Bristol University. They’ve spotted the striking fact that between 1997 and 2006 around half of the acute hospitals in England were involved in a merger. Their peer-reviewed results found little in the way of gains.”

These fixation errors are causing damage to the English NHS.

It’s time some people got out of the cockpit.

Care at the crossroads. Burnham has something big, and you may be quite pleased to see him

Social care funding is on its knees.

Andy Burnham MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Health, addressed a sympathetic audience at the #NHSConfed2014 yesterday, talking about unlocking resources for general medicine.

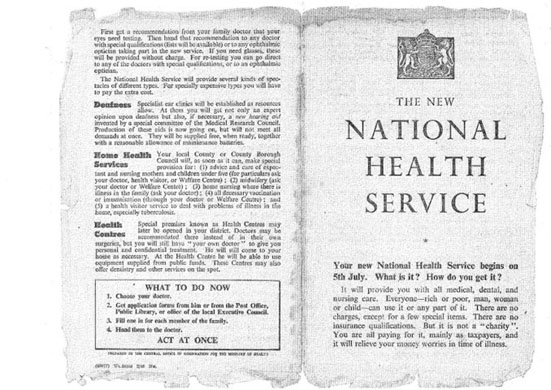

We live in crazy times. Newark saw the christening of the Conservative Party as the protest party you should vote if you wanted to STOP UKIP. But let me take you back to an era when the Labour Party had principles (!) In August 1945, Aneurin Bevan was made Minster for Health following the 1945 General Election. The National Health Service (NHS) was one of the major achievements of Clement Attlee’s Labour government. By July 1948, Minister for Health, Aneurin Bevan had helped guide the National Health Service Act through Parliament.

A full day has been allocated to the Opposition health on Monday in parliament in part of their discussions on her Majesty’s Gracious Speech. Simon Stevens – NHS England’s new chief – has asked for solutions for well rehearsed issues, and Andy Burnham is clear that this is no time for another apprentice like Jeremy Hunt. Whilst being upbeat about the future of the health and social care system, he wants to move away from a “malnourished system”, with carers employed on zero hours contracts and less than the minimum wage. Indeed, this is a serious issue which has caused me some considerably anxiety too. A “product of [my] time in Government”, clearly this framework has also benefited from a parliamentary term in opposition.

Burnham crucially identifies not an inefficiency in which money is spent (although the ongoing Nicholson savings rumble on). But he does identify an inefficiency in outcomes (such as the near-inevitable fractured neck of the femur in the leg for a seemingly-trivial cost-saving in not purchasing a grab handrail). Labour, inevitably, though has an uphill battle now. The system appears to encourage the medical model of care, according to Burnham, encourages hospitalisation of people, so it is not simply a question of throwing money at the service. People are more than aware that an ‘unsustainable NHS’ is in a nutshell code for a NHS starved of adequate fundings.

Burnham feels that you can’t half-believe in ‘integration’, and is mollified about the consensus about a need for integration across all main political parties.

“I am really worried that the ‘Better Care Fund‘ might give integration a bad name”, comments Burnham.

People who have watching Burnham’s comments will note how Burnham has openly commented how he feels he has been misled by certain think-tanks in the past. A period of opposition has enabled Burnham conversely to obtain a crisis of insight. And yet he talks about his “precious moment” in order “to build a consensus of shared endeavour, which I intend to use to the full and very carefully.” Intriguingly, he does not wish to ‘foist a grand plan’ on voters after the next general election. This is of course is political speak for his ‘shared agenda’, driving a cultural change by stakeholders within the system. This is precisely what Burnham feels he has achieved through the commission on whole person care by Sir John Oldham.

“Not a medical or a treatment model, but a truly preventative service, that can at last aspire to give people a state of physical, mental and social wellbeing.”

Burnham wants to put a stop to the ‘random set of disconnected meetings with individuals within the service.’

An exercise was carried out at the start of the NHS.

This is the famous leaflet.

Burnham desires a new leaflet from an incoming Labour government to introduce how social care can become under the umbrella of the National Health Service.

“Going forward, you should expect to receive much more support in your home. The NHS will work to assemble one team to look after you covering all the needs you have. We want to build a personal solution that works for you, for your family, and for your carers, because if we get right at the very outset and the very beginning it’s more likely to work for you and give you what you want, and cost us all much less. We want you to have one point of contact for the co-ordination of your care. We know you are fed up with telling the same story to everyone who comes through the door. It’s frustrating for you, and wasteful for us. To get the care that you’re entitled to, when and where you want it, you will have powerful new rights set out in the NHS Constitution such as the right to a single point of contact for the coordination of all of your care and a personalised care plan that you have signed off. But – and there is a big but – to make of all this happen, you will changes in your local NHS, and, in particular, you will changes in your local hospital. We can do a better job of supporting you where you want to be, we won’t need to carry out as much treatment in hospitals, or have as many hospital beds. It is only by allowing the NHS to make this kind of change to move from hospital to home that we will all secure it for the rest of this century.”

Burnham feels that the NHS must be the ‘preferred provider’ and the DGH should be allowed to reinvent itself - building the notion of one team around the person. I personally have formed the opinion: “close smaller hospitals at haste, and repent at leisure“. Critics of marketisation will inevitably point out the blindingly obvious: that even with a NHS preferred provider, there’s still a market, and nothing short of abolition of the purchaser-provider split will remedy the faultlines. There could be a one person tariff or one person budget for a person for a year. It would give an acute trust a much more stable platform, according to Burnham, in contradistinction to the activity based tariff. This does require some rejigging of how we have the proper financial performance management system in place: there should be a drive, I feel, for rewarding behaviours in the system that promote good health rather than rewarding disproportionately the work necessary to deal with failures of good control, such as dialysis, amputations or laser treatment.

Burnham is clearly inspired by the ‘Future Hospitals’ soundings from the Royal Colleges of Physicians, focused on a new generation of generalist doctors working across boundaries of primary and secondary care:

“Since its inception, the NHS has had to adapt to reconcile the changing needs of patients with advances in medical science. Change and the evolution of services is the backbone of the NHS. Hospitals need to meet the requirements of their local population, while providing specialised services to a much larger geographical catchment area.”

Burnham even talks about possibly reviewing the “independent contractor” status of GPs.

Centralised care is mooted for people in life threatening situations. But Burnham has found that barriers to service reconfiguration exist through the current competition régime and market, with integration encouraging in contrast to collaboration, people before profit, and merge “without the nonsense of competition lawyers looking over their shoulders”. Therefore, Burnham repeats his pledge to remove the Health and Social Care Act (2012), which has driven “fragmentation, complexity and greater cost”. Under this construct, section 75 and its associated Regulations is disabling rather than enabling for health policy. There is clearly much work to be done here to make the legislation fit for purpose, as indeed I have discussed previously. Wider dangers are at play, as Burnham well knows, however. Here he is speaking about his opposition to TTIP (the EU-US Free Trade Treaty) which the BBC News did not seed fit to cover despite their Charter requirements for public broadcasting. And here is George Eaton writing about his opposition to TTIP in the New Statesman.

Burnham is clearly, to me, positioning himself to the left, distancing himself from previous Labour administrations. There are clearly budgets in the system somewhere, and while Burnham talks about unified budgets he does not put the emphasis on personal budgets. There is no doubt to me that personal budgets can never be ‘compulsory’, and each person group (e.g. people living with dementia) presents with unique challenges. It’s clear to me that deep down Andy Burnham is still in principle keen on something like the ‘National Care Service’, in preference to any gimmicks from the Cabinet Office. Burnham in the Q/A session with Anita Anand indeed describes how this had been thrown into the long grass at the time of Labour losing the general election in 2010, but how paying for social care in 2014 is as fundamentally unfair as paying for medicine had been pre-NHS according to Burnham. This would take some time to put in place, such as a mechanism for a mandatory insurance system, and a proper care coordinator infrastructure. And these are not without their own controversies. But, with Miliband playing safe one unintended consequence for neoliberal fanatics has been that it has not been possible to impose a strong neoliberal thrust to whole person care; and whatever Miliband’s personal preferences, the pendulum to me is definitely swinging to the left. Burnham talks specifically about a well planned social care system as part of the NHS.

And so Burnham looks genuinely burnt by previous administrations, and, whilst certain key players will want personal budgets and competition to be playing a greater part in policy, it appears to me that the current mood music is for Labour not appearing to promote privatisation of the NHS in any form. The ultimate success of the next Labour administration will be determined by the clout of the Chancellor of Exchequer, whoever that is. It could yet be Ed Balls. For matters such as ‘purse strings’ on the social impact value bond or the private finance initiative, Burnham may have to slog out painful issues with Balls in the way that Aneurin Bevan once did with Ernie Bevin in a previous Labour existence. Burnham’s problem is ensuring continuity with the current system where services have been proactively pimped out to the private sector, but ultimately it is the general public who call the shots. Burnham knows he’s onto something big, and, for once, some people may be quite pleased to see him.

My personal experience of an introductory day to ‘Dementia Friends’ Champions

OK it’s not heaven on earth – but Kentish Town London does have some merits I suppose.

To say that I am passionate about the dementia policy in England is an understatement.

Throwing forward, I believe living well with dementia is a crucial policy plank (here’s my article in ‘ETHOS journal’), for which service provision needs a turbo boost through innovation (here’s my article co-written in Health Services Journal).

“Dementia Friends” in reality means rocking up in a venue somewhere near you for about 45 minutes to learn something about the dementias.

Once you sign up on their website, the experience is also backed up by an useful non-public website containing details of training, pre-training materials, and help on how to promote sessions. You can also provide on that website precise details of any ‘Dementia Friends’ information sessions that you run in due course.

I had known of this initiative mainly through Twitter, where I am very active. I find the twitter thread of @DementiaFriends interesting.

Even I’ve been known to get involved in a bit of mass hysteria myself:

I possibly signed up despite of the substantial interest in the media and social media, what psychoanalysts might call an “abreaction”. There’s a large part of me which feels that I do not need 45 minutes on dementia, having studied it for my much of my final undergraduate year at Cambridge, done my Ph.D., written papers such as this (one of which even appears in the current chapter on dementia in the Oxford Textbook of Medicine), written book chapters on it (which as this one which appears in a well known book on younger onset dementia), and even written a book on living well with dementia.

But Prof Alistair Burns is a Dementia Friend – and he’s the clinical lead for dementia in England.

I went out of curiosity to see how Public Health England had joined forces with the Alzheimer’s Society. I must admit that I am intensely loyal to the whole third sector for dementias, including other charities such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Young Dementia UK, Alzheimer’s BRACE, and Dementia UK.

I have my own particular agendas, such as a proper care system for England, with the provision of specialist nurses such as Admiral Nurses. I think some of the English policy is intensely complicated, best reserved for those who know what they’re talking about – especially people currently living with dementia and all carers including unpaid caregivers.

I personally think the name ‘dementia friendly communities‘ is ill conceived, but the ethos of having inclusive communities, well designed environments and ways of making life easier for people with certain thinking problems (such as memory aids, good signage) highly attractive. It would be unfair in my view for this construct to be engulfed in cynicism, when the fundamental idea is likely to be a meritorious one.

But I don’t think Dementia Friends competes with any of that, and one must be mindful of the gap society had of awareness of dementia.

This gap is still enormous.

And the aim is for people – not just Pharma – to be interested in dementia. These are real people with their own lives, not merely ‘potential subjects for drug trials’ (worthy that the cause of finding an effective symptomatic treatment or even cure might be potentially). But these are people living in the now – take for example the Dementia Alliance International, persons with dementia with beliefs, concerns and expectations of their own like the rest of us.

Only at London Olympia at the “Alzheimer’s Show” [and it is very well I am not a fan of such events which I have previously called "trade shows"], the other week, I presented at London Olympia for my ‘Meet the author session’, arranged on the kind invitation of various people to whom I remain very grateful.

At “The Alzheimer’s Show”, I met within the space of ten minutes a lady newly diagnosed with vascular dementia who did not intend to tell anyone of her diagnosis, and one person married to someone with probable dementia of the Alzheimer type who did not even tell his friends for three years.

It’s a rather badly articulated slogan but the saying ‘no decision made about me without me’ I think is particularly important for dementia.

These are two real (without warning) discussion points from the floor.

“Are people with dementia actually involved with any of the sessions?”

Yes: in fact my pal Chris Roberts (@mason4233) in Wales delivers his Dementia Friends sessions word-perfect for 45 minutes, without telling his audience that he himself lives well with dementia until the very end. Chris tells me this dispels, visibly, preconceived prejudices from his audience members. Chris blogs regularly on his blog, and has written for the ‘Dementia Friends’ blog.

“Why should people with dementia be given special elevated status compared to any other medical condition?”

It’s a difficult one. Some people believe that with dementias people will easily ‘snap out of it’ ‘if they pull themselves together’. This is completely at odds with one of the learning points that dementia is chronic and progressive. And of course people in the real world – viz CCG commissioners – have to decide how much they wish to prioritise dementia ahead of, instead of, etc. other medical conditions such as schizophrenia. But people living with dementia can present with known problems such as forgetting their pin number, and therefore it’s not actually a case about giving people with dementia an ‘elevated status’, but getting them up as individuals to be expected from anyone. Although it’s motherhood and apple pie, it’s very difficult to find, whatever the motive, the intention of dementia friendly high street banking fundamentally objectionable.

Dementia Friends Champions become rehearsed in the programme at one-day sessions across England. What happens is that you watch videos on their website, sign up for a day (where you get to take part in a Dementia Friends session) and then attend the session somewhere close to where you live habitually.

The sessions are run all over England at regular frequency. You sign up for a session, then you get an email quickly afterwards. You go to the meeting.

My meeting started on time. I am physically disabled, so I was grateful for easy access to the venue in Voluntary Action Camden (I could use the lift).

One of the things some of us mean-minded people pick holes in is whether the venue itself might be dementia-friendly. TICK.

I thought so.

The group dynamics worked really well.

My group consisted of interesting people, all ‘realistic’ in their expectations of shifting the Titanic of messaging of negative memes in the media. Many of my group were particularly interested in social equity, fairness and justice, reading between the lines.

I particularly enjoyed speaking with one delegate who is a NHS consultant in psychiatry. We went through pleasant niceties of what he was examined on in his professional membership exams (in his case the difference between schizophrenia and drug-induced psychosis). But he was great to chat to during the day.

I bored him to death with my example of persons with dementia putting numerous teaspoons of sugar in their cups of tea, on rare occasions, due to ‘utilisation behaviour’, a particular predilection for sweet foods since the onset of dementia, or cognitive estimates problem, a very niche area of cognitive neuropsychology for both of us. But this was simply in an activity on making tea where such private chit-chat was irrelevant; the actual session as delivered, on how to make a cup of tea, was far superior than the two hour version I did in a workshop for my MBA in that well known method known to managers: “process mapping“.

The whole day was presented by Hannah Piekarski (@HannahPiekarski), Regional Volunteering Support Officer for the London and South East region for “Dementia Friends.

I’ve sat through more presentations than you’ve had hot dinners, but the standard of the presentation was excellent. Although the presenter clearly had a corpus of statements to make, the presentation was not contrived at all, and the audience had plenty of opportunity to ask questions at points during the day. The presenter evidently knew what she was doing, and was a very good representative of the Dementia Friends programme. She gave her own ‘Dementia Friends’ session which the group of about twenty found faultless.

Hannah even ran a session after the lunch break on what makes a BAD presentation.

Here are my scrappy notes which I took – and please don’t take this to be representative of the actual discussion of what makes a bad presentation which we had in our group.

I SO wish some of my lecturers (including Readers and Professors) had been to Hannah’s session on generic skills in presentations. Whatever you do after ‘Dementia Friends Champions’ day, there’s no doubt that such a session is really useful across various sectors including law and medicine.

You don’t really have to take notes as it’s all fundamentally in their well laid out handbook.

The day was run with the purpose of not giving you tedious crap on how to run a session. But it was furnished with many useful pointers. For example, I learnt of possible venues such as a local library, church halls, and community centres.

Actually, I have in mind to ask Shahban Aziz, CEO of BPP Students, Prof Peter Crisp (Professor of Law at BPP Law School) and Prof Carl Lygo (also Professor of Law at BPP Law School) whether I might run dementia friend sessions at this law school which I attended for my pre-solicitor training. I’ve always had a bit of a discomfort that lawyers are not really given any introduction to dealing with people with dementia, other than professional regulatory considerations or in direct dealings with the law such as mental capacity? I think it’d be great if law students had a basic working knowledge of what dementias are.

It was nice for me to get out of my flat, and meet a range of people. These people ranged from other people in the third sector, for example the Dementia Action Alliance. They bothered to provide free coffee all day, and a free lunch.

And when I tweeted that on my @legalaware Twitter account from my mobile phone in the lunch break (you’re told to turn your mobiles off for the day), I received this smartarse (#lol) remark from one of my 12000 followers immediately.

You’re given a guidebook. You’re not coerced in any way into becoming a Dementia Friend or Dementia Friend Champion. You’re told specifically having done Dementia Friends you can do whatever point of action you wish, even if that includes supporting another charity other than the Alzheimer’s Society.

You are told that the point of the current dementia strategy in England in no way is intended to be political. In support of that claim is that the current strategy has overwhelming cross-party support.

The sessions include information about dementia and how it affects people, as well as the practical things that can be done to help people with dementia live well in their community.

I was given resources to answer people’s questions about dementia and suggest sources of further information and support.

After completing the course Dementia Friends Champions can access resources and tools to help set up and run sessions for people who sign up as Dementia Friends.

These resources include exercises, quiz sheets, bingo sheets, book club ideas and reading suggestions. You’re made very familiar with the content of ‘Dementia Friends’ as they helpfully provide ALL the material on the website when you sign up. They don’t hold any of it back. The point is you go away and run the whole session as ‘Dementia Friends’. Having seen how the 45 minutes works, I have no burning desire to change any of it.

Having said that, there are one or two things I would do differently, hypothetically. The format makes it very clear the presenter is not an expert in dementia or counsellor. I think this actually helps in that an expert possibly could write an hour long essay on each of the five statements for finals, and get truly bogged down in “paralysis by analysis”.

One of the possible features of the ‘Dementia Friends’ session is comparing dementia to a bookcase. This is a well described metaphor, first proposed by Gemma Jones. I have indeed used it to propose a scheme of explaining ‘sporting memories’, an initiative which recently won the Alzheimer’s Society Dementia Friendly Communities national initiatives awards.

Here’s my pal Tony Jameson-Allen picking up his gong.

There’s a bit in the explanation of the bookcase analogy that gets quite technical in fact.

With the presenter of the session having said that he or she is not an expert in dementia or counsellor, it seems counter-intuitive to me that there is an explanation of the organisation of memory using two highly technical locations in the brain, the hippocampus and amygdala. But things like that are not a ‘deal maker’ or ‘deal breaker’ for me. There’s an excellent video of a presentation of the bookcase analogy by Natalie Rodriguez floating around, in fact, but we were all encouraged to be explain the analogy ‘live’ in our sessions, ‘rather than playing the DVD’.

I have absolutely no problem with the material being pre-scripted. I used to supervise neuroscience and experimental psychology for various colleges at Cambridge between 1997 and 2000 inclusive, and, whilst the guidance for teaching that was not as intense, it’s fair for me to mention that supervisors knew exactly what they had to cover for their students to achieve at least an upper second in finals.

Dementia Friends Champions, like me, are then be encouraged to run Dementia Friends sessions at lunch clubs, educational institutions and other community groups, but it could also include ideas such as arranging a meeting to talk with a small group of friends.

I intend to run five sessions to achieve about 100 further dementia friends. I conceptually find targets anywhere quite odious, and see exactly where this ambition has come from (Japan). On the other hand, nobody is a clairvoyant. The fact the number exists at all (aiming for March 2015) is a testament that this programme is being taken seriously. Had the number been set at 400, then we would all have said ‘job done’ some time ago.

I am actually, rather, amazed that somebody somewhere has signed off for a national programme to invite ordinary members of the public to attend free of charge a day on delivering the Dementia Friends programme, with nice company, and of course that free coffee and lunch.

I am also amazed that the actual substrate of the information sessions for ‘Dementia Friends’ is being offered to the member of the public free of charge, and it effectively has been paid for by Government.

The operational delivery of ‘Dementia Friends Champions’ day was totally faultless from start to finish. Even though I have nothing to do with their output, the Alzheimer’s Society here in England have done a brilliant job with it.

And finally I’ve tended to query whether it can be a genuine ‘social movement’ which so much resource allocation.

But people are genuinely interested in the programme, as these tweets to me demonstrate, I feel:

Look.

There are all sorts of things which do irritate me such as the issue that any dementia awareness should observe boundaries. For example, there are also many global ‘Purple Angels’ motivated by the leadership of Norman McNamara (@norrms), himself living with dementia of diffuse Lewy Body Type.

Here’s their brand new website. Norman is a very good friend of mine, so I’m bound to be loyal to him.

In a different jurisdiction – Australia – a close friend of mine, Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer), blogs daily on her busy life living with dementia, which includes being an advocate, travelling, cuisine (Kate is very experienced in sophisticated cooking), a background in healthcare, a student at the University of Wollongong, and what’s it like to live with dementia after being given the diagnosis. Her blog is here.

Chris, Norrms and Kate are all quite different – like the rest of the population – getting on with their lives. And as the very famous adage goes, once you’ve met one person living with dementia, you’ve done exactly done. You’ve met only one person with dementia.

And there’s clearly a huge amount to be done. Also at the Alzheimer Show one carer reported a person with dementia being ‘lost to the system’, completely unknown to anyone for care for three years.

I had a huge volume of concerns about this initiative, and I’m no pushover as far as being ‘in with the in-gang’ is concerned. But I strongly recommend you park your misgivings and go there wanting to be a part of a “change”.

I went on the day after the passing away of the incredible Dr Maya Angelou.

As she said, “If you don’t like something, change it. If you can’t change it, change your attitude.”

Ed Miliband should not be so obsessed about the economy, but talk about the NHS

Time after time, voters in polls and in focus groups return the finding that they don’t especially trust any mainstream political party with their handling of the economy.

But in a forced choice, a small majority of voters think the Conservatives are ‘better at handling the economy’.

This of course depends on what your definition of the economy is. If it means the rich getting a lot richer, that is possibly true. And don’t forget Lord Mandelson was ‘intensely relaxed about that too’.

Gordon Brown and Ed Balls are adamant that they’ve won the argument on needling to pump money into the investment banking sector to avert a ‘Great Recession’.

However, David Cameron and Nick Clegg appear to have succeeded in spinning repetitively their yarn that it was Labour that ‘brought the economy to its knees’.

And it seems Ed Miliband is equally obsessed about ‘winning the argument’. Miliband is continuing with the line that the cost of living outstrips real wages, even though it is widely reported that this trend will reverse sometime this year.

But Miliband possibly is on surer ground with ‘zero hour contracts’, and the financial insecurity of some who have them. He would be on massively firmer ground if he were to attack the lack of access of justice through the closure of law centres through legislation introduced by this Government.

He would be on much firmer ground if here were to attack the changes in employment rights such as unfair dismissal.

There’s no doubt that the ‘cost of living crisis’ is important to many – with the well known #shockedface when many of us open our energy bills.

But he almost appears to mention the NHS as an after thought. Now is the time when Labour should produce a series of announcements on what it wants to do, aside from leaks on public health which look pretty deliberate in the Daily Mail.

Labour could campaign strongly to ensure that the English Law Commission’s proposals on the regulation of clinical professions see the light of day, with Jeremy Hunt having made this such a totemic issue.

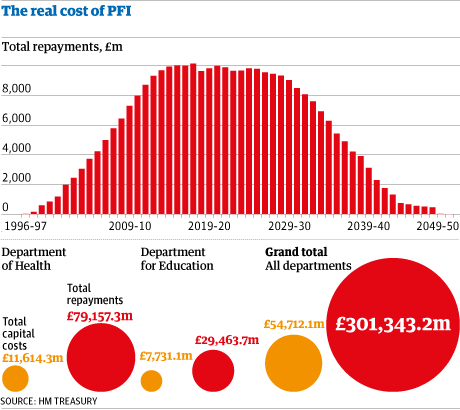

Labour could hone in on the incredible waste in PFI loan repayments, and their subsequent effect on budgets regarding safe staffing. These have been identified by Margaret Hodge’s team in the Public Accounts Committee.

It could decide to wish to implement legislation which makes it a certainty there’ll be no hospital closures appearing from nowhere and any discussion of changes to health services will require a meaningful discussion with the local community first.

It is up to Labour to choose the narrative too. People desperately want Labour, and Ed Miliband, to take a lead on the NHS. As Carville said, “It’s the economy stupid….. but don’t forget about healthcare.”

A person newly diagnosed with dementia has a question for primary care, and primary care should know the answer

Picture this.

It’s a busy GP morning surgery in London.

A patient in his 50s, newly diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, a condition which causes a progressive decline in structure and function of the brain, has a simple question off his GP.

“Now that I know that I have Alzheimer’s disease, how best can I look after my condition?”

A change in emphasis of the NHS towards proactive care is now long overdue.

At this point, the patient, in a busy office job in Clapham, has some worsening problems with his short term memory, but has no other outward features of his disease.

His social interactions are otherwise normal.

A GP thus far might have been tempted to reach for her prescription pad.

A small slug of donepezil – to be prescribed by someone – after all might produce some benefit in memory and attention in the short term, but the GP warns her patient that the drug will not ultimately slow down progression consistent with NICE guidelines.

It’s clear to me that primary care must have a decent answer to this common question.

Living well is a philosophy of life. It is not achieved through the magic bullet of a pill.

This means that that the GP’s patient, while the dementia may not have advanced much in the years to come, can know what adaptations or assistive technologies might be available.

A GP will have to be confident in her knowledge of the dementias. This is an operational issue for NHS England to sort out.

He might become aware of how his own house can best be designed. Disorientation, due to problems in spatial memory and/or attention, can be a prominent feature of early Alzheimer’s disease. So there are positive things a person with dementia might be able to do, say regarding signage, in his own home.

This might be further reflected in the environment of any hospital setting which the patient may later encounter.

Training for the current GP is likely to differ somewhat from the training of the GP in future.

I think the compulsory stints in hospital will have to go to make way for training that reflects a GP being able to identify the needs of the person newly diagnosed with dementia in the community.

People will need to receive a more holistic level of support, with all their physical, mental and social needs taken into account, rather than being treated separately for each condition.

Therefore the patient becomes a person – not a collection of medical problem lists to be treated with different drugs.

Instead of people being pushed from pillar to post within the system, repeating information and investigations countless times, services will need to be much better organised around the beliefs, concerns, expectations or needs of the person.

There are operational ways of doing this. A great way to do this would be to appoint a named professional to coordinate their care and same day telephone consultations if needed. Political parties may differ on how they might deliver this, but the idea – and it is a very powerful one – is substantially the same.

One can easily appreciate that people want to set goals for their care and to be supported to understand the care proposed for them.

But think about that GP’s patient newly diagnosed with dementia.

It turns out he wants to focus on keeping well and maintaining his own particular independence and dignity.

He wants to stay close to his families and friends.

He wants to play an active part in his community.

Even if a person is diagnosed with exactly the same condition or disability as someone else, what that means for those two people can be very different.

Once you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve done exactly that: you happen to have met one person with dementia.

Care and support plans should truly reflect the full range of individuals’ needs and goals, bringing together the knowledge and expertise of both the professional and the person. It’s going to be, further, important to be aware of those individuals’ relationships with the rest of the community and society. People are always stronger together.

And technology should’t be necessarily feared.

Hopefully a future NHS which is comprehensive, universal and free at the point of need will be able to cope, especially as technology gets more sophisticated, and cheaper.

Improvements in information and technology could support people to take control their own care, providing people with easier access to their own medical information, online booking of appointments and ordering repeat prescriptions.

That GP could herself be supported to enable this, working with other services including district nurses and other community nurses.

And note that this person with dementia is not particularly old.

The ability of the GP to be able to answer that question on how best her patient can lead his life cannot be a reflection of the so-called ‘burden’ of older people on society.

Times are definitely changing.

Primary care is undergoing a silent transformation allowing people to live well with dementia.

And note one thing.

I never told you once which party the patient voted for, and who is currently in Government at the time of this scenario.

Bring it on, I say.

Burnham goes from strength to strength as ‘striker’, but who’s the David Moyes?

There’s no doubt Andy Burnham MP drives the Conservatives potty.

Despite the Conservatives’ best attempts to annihilate Burnham MP, Burnham keeps on scoring goals.

Meanwhile Jeremy Hunt continues to score blanks, apart from where profits from ‘Hot Courses’ are concerned.

But Burnham is more concerned about the day job, and that is running the NHS to a level of some degree of competence.

Hunt meanwhile continues to run his NHS into the ground, paying for costly advice on the managerial implementation of compassion, when he could be paying nurses to do the professional job they’re trained to do.

So Burnham can certainly hold his head up high as chief striker or scorer for Labour United.

As the Conservatives spit out the oranges from their half-time pep talk, as the oranges were in fact horsemeat due to the abolished Food Safety Agency, it’s time to recapitulate.

Clive Peedell kindly tweeted the other day points on which he would like Labour to play ball.

@legalaware @andyburnhammp 1. Fill £30bn funding gap by abolishing PFI & cracking down on tax avoidance 2. Get NHS exempted from TTIP

— Clive Peedell (@cpeedell) April 22, 2014

Before the 2010 election, Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg indeed condemned PFI as “a bit of dodgy accounting – a way in which the government can pretend they’re not borrowing when they are, and we’ll all be picking up the tab in 30 years”. It’s well known that PFI is a relic of the John Major government from 1995 (predating New Labour in fact). In opposition, Osborne pledged that the Conservatives would stop using PFI and denounced Labour for relying so much on a source of finance that he said was “totally discredited”. “We need to find new ways to leverage private-sector investment. Labour’s PFI model is flawed and must be replaced,” Osborne muttered in November 2009. Indeed Margaret Hodge, chair of the powerful Commons public accounts committee, said the coalition had failed to come up with the promised alternative since coming to power. The facts speak for themselves.

And Burnham is handicapped by not being the actual Secretary of State for Health at this crucial time for the NHS.

He nonetheless did go to Strasbourg last month to try to explain the case:

(This is a video recording I took of Andy’s talk at the Southwark Labour meeting recently.)

Labour will need to abolish PFI contracts or renegotiate them or both. But Ed Balls will need to be on the wing to help Burnham shoot. And it’s hoped the football manager is not asleep on the job. Labour has indeed proposed a five point plan to tackle ‘tax avoidance’. Labour supports a form of country-by-country reporting. It would extend the Disclosure of Tax Avoidance Schemes regime, which Labour introduced, to global transactions. It would open, further, open up tax havens, with requirements to pass on information about money which is hidden behind front companies or trusts. Crucially, Labour also wants to see fundamental reform of the corporate tax system. But Peedell’s work is not done.

@legalaware @andyburnhammp 3. Abolish purchaser provider split 4. Improve NHS accountability with transparency & openness — Clive Peedell (@cpeedell) April 22, 2014

The abolition of the purchaser-provider split remains one of the totemic political decisions to be made, as is not a ‘deal maker’ for many grassroots voters.

In fact, the whole issue of whether the general public is interested by public health or competition remains uncertain.

Nonetheless, a pioneering integrated healthcare scheme in New Zealand has improved the care of patients while reducing demand on hospital services.

On the contracting side, the report said that the abolition of the purchaser-provider split in the health system was important as it gave boards the autonomy to decide how to fund their hospitals.

The project was launched in 2007 in response to rising hospital admissions and waiting times and to a population that was ageing more rapidly than in other parts of New Zealand and other developed countries.

Similar to the drive towards whole person care in this jurisdiction, is aim was to create a “one system, one budget” approach to health and social care, together with various aspects as centrepieces: sustained investment in training, support for staff to innovate, and new forms of contracting, including abolition of the split between healthcare service purchasers and providers.

The outgoing NHS England chief executive Sir David Nicholson last year told HSJ his organisation was looking at “whether the straightforward commissioner-provider split is the right thing for all communities”.

Hospitals wish to focus on delivering better services to patients and often get frustrated by the amount of time they have to spend negotiating contracts with commissioners with the legal shutgun pointing in the direction of their necks.

And there’s no doubt there’s a steady stream of whistleblower tragedies, with Raj Mattu the latest in the long line of casualties.

People still struggle to think of a NHS whistleblower who has had a good outcome.

The Nursing Times ‘Speak Out Safely’ has only so far succeeded in signing up 30% of NHS Trusts.

Most people accept that the whole system is rotten, not least in how clinical regulators appear to pass the buck or even worse target whistleblowers.

Many do not think the Public Interest Disclosure Act, enacted by New Labour is 1998, is fit for purpose either.

So Clive Peedell is right, but Andy Burnham may have trouble in shooting goals on target with nobody on wing or a manager more concerned about ‘One Nation’.

Moyes, sacked by United on Tuesday after the 2-0 defeat at former club Everton on Sunday confirmed their failure to secure Champions League qualification, oversaw just 51 games in charge of the team after succeeding Sir Alex Ferguson last summer.

Moyes, like Ed Miliband, though had his army of people who thought he was doing a good job.

But Burnham like many, although focused on sorting out the undeniable problems of the NHS, is avoiding relegation for his team too.

I certainly don’t want to ask who the Ryan Giggs is. That certainly would be tempting fate.

Social enterprises and the NHS: who benefits and what’s at stake?

As social enterprises for care get promoted in England, such that they literally get ‘bigger and bigger’, now’s a sensible time to task who exactly benefits and what’s at stake.

Like personal budgets or PFI, a discussion with the public is unlikely to be forthcoming in the near future. Nonetheless, it’s possible to make some inroads into this complicated narrative. At the beginning of this parliament, the Department of Health declared its vision that the NHS should be the “largest social enterprise sector in the world” through the liberation of foundation trusts, and handing over services to NHS staff. Enhancing the role of social enterprises and mutuals in public service provision was right at the heart of the Coalition Government’s vision of the “Big Society”, and part of the aspiration to move one in six public sector jobs into staff-owned companies.

In a somewhat provocatively titled article in the Health Services Journal, “Norman Lamb: Mid Staffs would never have happened at a mutual”, Health minister Norman Lamb suggests that acute trusts could improve staff engagement by becoming social enterprises and argued that the culture problems seen at Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust would never happen in a mutually-owned company. It is not any surprise to anyone who has worked as a clinician in the last decade in the NHS that understaffed services, perhaps cut back as a result of ‘efficiency savings’ to help address ‘the funding gap’, have been the major threat to patient safety in NHS hospitals and Foundation Trusts.

The Berwick Report discusses safe staffing ratios, and staff engagement is a pervasive theme in the whole analysis. And yet curiously the document “The Care Bill explained: Including a response to consultation and pre-legislative scrutiny on the Draft Care and Support Bill“, which indeed calls Mid Staffs a “watershed moment in care”, does not mention social enterprises or mutuals once.

The famous Norman Lamb/Chris Ham review is due to report imminently.

Meanwhile, the Cabinet Office ‘Mutuals Information Service” has a feeling about it of “Well done on setting up your first mutual!”

“Setting up a mutual is a major achievement… However, the transition from the public sector can bring significant challenges… The biggest challenge that comes with leaving the public sector, though, is having to operate as a business. In the first year, you will be focussed on delivering your service and making your mutual work. However, as you build your experience and look to the future, you should start to think about opportunities for expansion and growth.”

All organisations involved in care have have had a tension between board members acting as representatives for particular membership groups and ‘experts’ charged with driving the performance of the organisation forward.

Social enterprises are non-profit ventures designed to achieve both social and commercial objectives. Although trading for a social purpose is hardly a new phenomenon (Hall, 1987), the growth of social enterprise has been a key feature of economic activity in both developed and developing countries.They are hybrid organisations that have mixed characteristics of philanthropic and commercial organisations (Dees, 1998).

According to Alter (2006), social enterprises are driven by two forces:

“first, the nature of the desired social change often benefits from an innovative, entrepreneurial, or enterprise-based solution. Second, the sustainability of the organisation and its services requires diversification of its funding stream, often including the creation of earned income opportunities (p. 205).”

It’s already known the accountability and transparency (corporate governance) mechanisms of social enterprises aren’t always necessarily “fluffy”: see for example this interesting discussion of “asset locks”. Co-operatives have long held to have three groups of participants, according to Johnston Birchall and Richard Simmons (2004). They are: those “true believers” who can be persuaded to train as potential board members, those who can be formed into a kind of club who believe in the aims of the organisation and will participate through voting, attending annual meetings and social events, and supporting campaigns such as fair trade, and a third group which is quite ambivalent.

Birchall and Simmons review that the best way to encourage active participation amongst membership is to reinforce the values of mutuality, engage widely with the community, and to make accountability central to corporate governance and strategy. And “non-uniform engagement” is a well-documented issue with NHS Foundation Trusts (FTs) too. Nonetheless, managers in FTs have described using members of public to give their governance a sense of legitimacy (Allen et al., 2012):

‘They are seen as a very important strategic weapon . . . the governors and their influence into the community, is really, really key’

Multinational corporations have an interest in working with the community too. The construct of ‘corporate social responsibility is important for such corporations to gain ‘competitive advantage” through “value creation” (Husted and Allen, 2007). The European Commission identifies corporate social responsibility as: “a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis” (Commission of the European Communities 2001).

Recent examples of the failure of private providers to deliver NHS services, such as Serco with its contract for older people’s services in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough CCG, have led to a greater desire within the NHS to see commissioning in terms of how a provider can deliver a long-term business model with greater social value, going beyond the cost-effectiveness of their work. That’s where social enterprises come in so handy for multi-national companies, and vice versa. And as you progress down the ‘You too can set up a mutual’ aspirational route, you as a member find yourself less interested in real persons and real patients, but get more bogged down with the “bottom line”. Though the field is young, it’s clear private equity want a slice of the action: the “Socially Responsible Investment” is an investment process that integrates social, environmental, and ethical considerations into investment decision-making (Crifo and Forget, 2013).

From a somewhat corporate perspective, Antony Bugg-Levine, Bruce Kogut, and Nalin Kulatilaka gave a neat description of the “social impact bond” in the Harvard Business Review in 2012:

“Another innovation, the social impact bond, deserves special notice for its ability to help governments fund infrastructure and services, especially as public budgets are cut and municipal bond markets are stressed. Launched in the UK in 2010, this type of bond is sold to private investors who are paid a return only if the public project succeeds—if, say, a rehabilitation program lowers the rate of recidivism among newly released prisoners. It allows private investors to do what they do best: take calculated risks in pursuit of profits. The government, for its part, pays fixed return to investors for verifiable results and keeps any additional savings. Because it shifts the risk of program failure from taxpayers to investors, this mechanism has the potential to transform political discussions about expanding social services.”

However, this approach has already been likened to a ‘private finance initiative’ for social enterprises. The critical issue then becomes “he who pays the piper calls the tune”, and membership engagement becomes even more murky. Any steady income source can have its drawbacks. For example, according to the “crowding-out hypothesis”, an increase in one source of revenue, such as a government grant, can lead to a decrease in revenue from other sources, such as private donations (e.g., Weisbrod 1998).

So in answer to my original question, private investors stand to benefit while public sector budgets get cut (which could be easier to hide anyway through integrated care or ‘whole person care’ in the next parliament), and what’s at stake is that membership engagement gets worse as the social enterprises get bigger and bigger. But would this policy plank, in fact, prevent another Mid Staffs as Norman Lamb would perhaps like us to believe?

Selected readings

Allen, P., Townsend, P., Wright, J., Hutchings, A., Keen, J. (2012) Organizational Form as a Mechanism to Involve Staff, Public and Users in Public Services: A Study of the Governance of NHS Foundation Trusts, Social Policy & Administration, 46(3), June, pp. 239–257.

Alter, S.K. (2006) Social Enterprise Models and Their Mission and Money Relationships. In A. Nicholls (Ed.), Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change: Oxford University Press

Birchall, J, Simmons, R (2004) The Involvement of Members in the Governance of Large-Scale Co-operative and Mutual Businesses: A Formative Evaluation of the Co-operative Group, Review of social economy, LXII, 4.

Bugg-Levine, A., Kogut, B., Kulatilaka, N. (2012) A New Approach to Funding Social Enterprises, January–Harvard Business Review, February, pp. 119-123.

Crifo, P, Forget, V.D. (2013) Think Global, Invest Responsible: Why the Private Equity Industry Goes Green, J Bus Ethics, 116, pp. 21–48.

Dees, J. G. (1998). Enterprising nonprofits, Harvard Business Review, pp. 55-67.

Hall, P.D. (1987) A historical overview of the private nonprofit sector, In The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook. Powell WW (ed.). Yale University Press: New Haven, CT; pp. 142–175.

Husted, B.W., Allen, D.B. (2007) Corporate Social Strategy in Multinational Enterprises: Antecedents and Value Creation, Journal of Business Ethics, 74, pp. 345–361

Piercy, N.F., Lane, N. (2009) Corporate social responsibility: impacts on strategic marketing and customer value, The Marketing Review, 9(4), pp. 335-360.

Weisbrod, B.A. (1998), The Nonprofit Mission and Its Financing: Growing Links Between Nonprofits and the Rest of the Economy, in To Profit or Not to Profit: The Commercial Transformation of the Nonprofit Sector, B. Weisbrod, ed. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–24.

That you can safely assume the recovery won't benefit the NHS speaks volumes

Chancellor George Osborne is hailing the UK’s economic recovery in a keynote speech in Washington DC as we speak.

Mr Osborne said has critics of the government’s economic plan have been proved “comprehensively wrong”.

His chest-beating lap of honour after the International Monetary Fund said Mr Osborne’s austerity policies were “playing with fire”.

Speaking while in the US capital for the spring meetings of the IMF and World Bank, the chancellor said that cutting deficits and controlling spending had “laid the foundations for sustainable growth”.