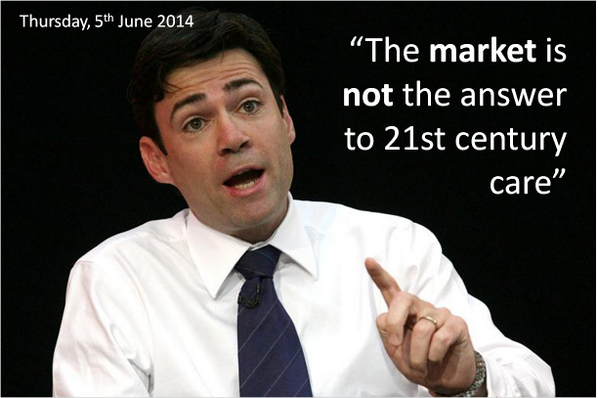

A series of different amendments are coming from various sources to ask Andy Burnham to scrap the market in the NHS.

And indeed Andy Burnham claims to be well aware of the dangers of the introduction of a sort of-market to the NHS:

In recent years, there has been clear unease at policy wonks ‘doing’ the traditional circuits in think tanks, known to feather each other’s nests, with no clinical backgrounds (including no basic qualifications in medicine or nursing), pontificating at others for a cost and price how to run the NHS in England.

Think tanks have been part of the discussion, with blurred lines between marketing and shill and academic research, exasperating the real research community.

The King’s Fund boasts that, “Providing patients with choice about their care has been an explicit goal of the NHS in recent years. Competition is viewed by the government as a way of both providing that choice and giving providers an incentive to improve. The Health and Social Care Act set out Monitor’s role as the sector regulator with a specific role of preventing anti-competitive behaviour in health care.”

Chris Ham, who has previously marvelled voluptuously at the US provider Kaiser Permanente in the British Medical Journal, goes hammer and tong at it on an article on competition here.

The theme or meme comes up as a recurrent bad smell in the impact assessment for the Health and Social Care Bill here, citing in the need to consider equality concerns in competition the reference Gaynor M, Moreno-Serra R, Propper C, (July 2010) Death by Market Power Reform, Competition and Patient Outcomes in the National Health Service. NBER Working Paper No. 16164, July 2010.

The authors of that impact assessment nonetheless reassuringly observe that “Gaynor et al (2010) found competition impacted differently across certain areas with possible negative impacts on transgender and black and minority ethnic (BME) people. However, further evidence implies that these risks, associated with increasing competition, should not be overstated and may not impact upon equality issues.”

Andy Burnham – and Labour – have pledged many times that the repeal of the failed Health and Social Care Act (2012) will be in the first Queen’s Speech of a Labour government.

Policy wonks are human beings, and can fail.

It is well-known that many errors in anesthesiology are human in nature. It’s argued that because equipment failure is an infrequent explanation for mishaps in the hospital, clinicians should be aware of the human factors that can precipitate adverse events.

While there are various types of human errors that can lead to complications, “fixation errors” are relatively common and deserve particular attention. Fixation errors occur when clinicians concentrate exclusively on a single aspect of a case to the detriment of other more important features. This is exactly what has happened with the undue prominence of the benefits of competition in the NHS.

Put simply, without any of the bullshit, competition is simply the crow bar which puts private providers into the NHS.

Milburn and Hewitt have been reading from this narrative from ages, and it threatens to engulf Labour yet again. Burnham is fighting a battle for the soul of the party now, and one can only speculate how successful he will be. He has said on many occasions that collaboration is the key to running the NHS in England, not competition; integration not fragmentation; people before profit.

But if you look beyond the lobbying – you can find the evidence right before your eyes. Jonathon Tomlinson through an excellent blogpost of his refers to a large body of literature from Professor Don Berwick which has been in the literature. This is clearly worth revisiting now.

The New Statesman published last week an article which should make senior healthcare policy wonks in England weep.

Martin Bromiley is neither a doctor, or a health professional of any kind. He is not even a member of the revolving door policy wonks in English healthcare policy. Bromiley is an airline pilot.

“Early on the morning of 29 March 2005, Martin Bromiley kissed his wife goodbye. Along with their two children, Victoria, then six, and Adam, five, he waved as she was wheeled into the operating theatre and she waved back.”

A room full of experts were fixated on intubating her, instead of doing a tracheostomy, which indeed Bromiley indeed asked for. A tracheotomy is a cut to the throat to allow air in.

What happened next was incredible.

“If the severity of Elaine’s condition in those crucial minutes wasn’t registered by the doctors, it was noticed by others in the room. The nurses saw Elaine’s erratic breathing; the blueness of her face; the swings in her blood pressure; the lowness of her oxygen levels and the convulsions of her body. They later said that they had been surprised when the doctors didn’t attempt to gain access to the trachea, but felt unable to broach the subject. Not directly, anyway: one nurse located a tracheotomy set and presented it to the doctors, who didn’t even acknowledge her. Another nurse phoned the intensive-care unit and told them to prepare a bed immediately. When she informed the doctors of her action they looked at her, she said later, as if she was overreacting.”

This is not the first time that a ‘fixation error’ has had disastrous consequences.

Another example happened on 28 December 1978, the United Airlines Flight 173.

A flight simulator instructor Captain allowed his Douglas DC-8 to run out of fuel while investigating a landing gear problem.

It’s a miracle that only ten people were killed after Flight 173 crashed into an area of woodland in Portland; but the crash needn’t have happened at all.

In a crisis, the brain’s perceptual field narrows and shortens. We become seized by a tremendous compulsion to fix on the problem we think we can solve, and quickly lose awareness of almost everything else. It’s an affliction to which even the most skilled and experienced professionals are prone.

In March 2012, Professor Allyson Pollock wrote an article in the Guardian, stating ‘Bad science should not be used to justify NHS shakeup’.

In this article, Pollock argued that pro-competition arguments from economists Julian Le Grand and Zack Cooper at the London School of Economics had produced an incredibly distorting effect on what was an important discussion and, “[raised] serious questions about the independence and academic rigour of research by academics seeking to reassure government of the benefits of market competition in healthcare.”

Pollock argues that such colleagues had been sufficiently successful for David Cameron to declare “Put simply: competition is one way we can make things work better for patients. This isn’t ideological theory. A study published by the London School of Economics found hospitals in areas with more choice had lower death rates.”

It is reported in one case, the previous chief of NHS England, Sir David Nicholson KCB CBE “said a foundation trust chief executive had been told he could not “buddy” with a nearby trust ? under plans announced last week to help struggling providers ? because “it was anti-competitive”.

He continued: “I’ve been somewhere [where] a trust has used competition law to protect themselves from having to stop doing cancer surgery, even though they don’t meet any of the guidelines [for the service].”

“Trusts have said to me they have organised, they have been through a consultation, they were centralising a particular service and have been stopped by competition law. And I’ve heard a federated group of general practices have been stopped from coming together because of the threat of competition law.”

“All of these [proposed changes] make perfect sense from the point of view of quality for patients, yet that is what has happened.”

Meanwhile, there was more product placement for providers including Kaiser Permanente yesterday by Jeremy Hunt in parliament:

“From next year, CCGs will have the ability to co-commission primary care alongside the secondary and community care they already commission. When combined with the joint commissioning of social care through the better care fund, we will have, for the first time in this country, one local organisation responsible for commissioning nearly all care, following best practice seen in other parts of the world, whether Ribera Salud Grupo in Spain, or Kaiser Permanente and Group Health in the US..”

Everyone appears to be fixated apart from the most junior in the room, or people like me who wouldn’t want to touch these jobs in think tanks with a barge pole.

It is indeed a badge of honour for me that the feeling is likely to be mutual.

Competition does not explain whether a person who has had chest pains due to a clogging heart should have a physical stent to open up the pipes of blood in his heart, or whether he needs tablets he can take. That is down to clinical professional acumen.

Competition with few big providers can lead to massive rip offs in prices, because of the way these markets work (these markets are called ‘oligopolies‘).

And all too easily providers can be in a race to the bottom on quality, cutting costs to maximise profits.

Remember Carol Propper’s research being used to bolster up the failed plank of competition in the Health and Social Care Act impact assessment?

Wow.

Here she is again in the speech by Simon Stevens, the new NHS England chief, being used in a slightly new context for his speech before the NHS Confederation last week: of the “sensible use” of competition in the NHS (somewhat reminiscent of the use of the words “sensible use” in the context of another potentially disastrous area of policy – targets):

“If we want to be evidence-informed in our policy making and commissioning lets pay heed to research from Martin Gaynor, Mauro Laudicella and Carol Propper at Bristol University. They’ve spotted the striking fact that between 1997 and 2006 around half of the acute hospitals in England were involved in a merger. Their peer-reviewed results found little in the way of gains.”

These fixation errors are causing damage to the English NHS.

It’s time some people got out of the cockpit.