Home » Posts tagged 'healthcare'

Tag Archives: healthcare

We've just had a huge debate about the NHS. It's just a pity that it's been the wrong one.

Think of how much time we’ve just all spent, in thinking about the way in which services will be mostly put out for competitive tendering in the National Health Service. One of the first rules in law is that you fight your battles to the hilt, but, at first, you pick the right battles first. This is precisely what Labour appears not to have done. When Harriet Harman recently said on Question Time that the Conservatives are definitely not ‘to be trusted with the NHS’, Harriet curiously did not refer to the battle and war just won by the Conservatives (and Liberal Democrats) over NHS procurement. And yet the public desperately want Labour to stand up for the NHS. One member even suggested that, if Labour gave its unequivocal backing for restoring the NHS, Labour could even find itself with a massive vote winner.

Labour is clearly going through policy strands with a fine tooth comb, looking at, for example, the way in which multinational companies might employ workers at below the national minimum wage; effectively, controlling immigration through a wage policy. It does not appear to have worked out unequivocally whether it would reduce the rate of VAT, meaning possibly that the state borrowing requirement would temporarily increase. But do you see what they all did there? For days, weeks, or even months, we have been subjected to a relentless debate about EU immigration, when most surveys probably place the issue at number ten on the list of voters’ concerns. Unsurprisingly, the economy remains in ‘pole position’, but the ability of Labour to turn the opinion of the public, particularly in the South of England, away from the idea that Labour is ‘fiscally incontinent’ remains unconvincing. Labour is still considered to be the “tax and spend” party, for example, and Miliband appears painfully aware of that. So, when it comes to policy, there seems to be an odd combination of Labour shooting itself in the foot, or completely picking the wrong battles. And then you add in a complete inability to look at elephants in the room. Labour, to state the obvious, has no ability to implement any of its policies, if it is unable to win a General Election, and the confidence of Labour to win an election on its own is reflected accurately in Lord Adonis promoting his book that ‘if he were to form a new Lib-Lab pact, he wouldn’t start from here.‘

The NHS remains pivotal in Labour’s electoral chances, and Labour has been unable to use the resentment over the section 75 NHS regulations to maximise political capital. Why this should have happened in itself is interesting, as Andy Burnham, MP for Leigh, is a more than capable Shadow Secretary of State for Health. One of the issues is an ability to choose the right battle, possibly. Burnham, with some support from the right-wing media and thinktanks, has been banging on about integrated and whole-person care. Whether through conspiracy or cock-up, there will be short-term interest in how integrated care might be delivered. Think about a justification for State spending in the ‘mission impossible’ of implementing a NHS IT system. Why on earth would a right-wing libertarian government promote something which is national? Why on earth should you abort an ethos of ‘bonfire of the QUANGOs’ to introduce the biggest QUANGO in the country, viz NHS England? Whether you’re into conspiracy or cock-up, the integration of financial and medical information (including mental, physical and social care systems) allows for the perfect infrastructure for an insurance-based system. Insurance works on the basis of misrepresentation or non-disclosure to invalidate claims, so ‘big data’ serve a perfect storm for this. It won’t have escaped anybody’s attention that Labour (as indeed the Conservative Party) has been heading towards an insurance-based system for social care, so it does not require a massive ideological leap to think how this could be extended for all care with time. This does not involve any degree of paranoia, please note.

There is overwhelmingly an intellectual depravity in the bereft notion of producing policy through poll results and focus groups. New Labour clearly loved focus groups, with Philip Gould in ‘The Unfinished Revolution’ having devoted much airspace to developing a product in line with customers’ wishes. Of course, the Conservatives have a special affinity for polling organisations themselves, Nadhim Zadawi, in 2000 he co-founded YouGov and on its flotation became its CEO. YouGov is now one of the world leaders in political and business information gathering, polling and analysis. It employs over 400 staff on three continents and is listed on the London Stock Exchange. Again – it begs the question on why should Labour should wish to outdo the Conservatives on its own ability to use polling data? One of the polls which has become a toxic meme is how a high proportion of all voters would not mind who provides the NHS services, as long as it’s free at the point of use. However, this is intrinsically linked to other questions. Would you be prepared more in national insurance if it meant the NHS were able to provide a more comprehensive (universal) service?

It is indeed correct to state that the costs of renationalising the NHS might be overwhelming, although no accurate costings of this have ever been discussed properly. We do know, however, that the current cost of the NHS reorganisation is in the region of £3bn, but estimates of the actual cost inevitably have to be taken with a pinch of salt, as say the cost of Margaret Thatcher’s funeral. But to use this issue as a wish to stop discussion of this area is lazy, as one of the issues, as indeed as with Thatcher’s funeral, is that is this a sensible use of money compared to how it could be used elsewhere (so called “opportunity cost“)? Some people argue that the marketisation of the NHS has failed, in that any money spent on restoring a state-funded NHS would be money well spent. Restoring a state-funded service would get out of the idea of private companies being driven by maximising their profit margin, and not running a ‘more for less’ approach for delivering a service. Cynics might argue that the cost of restoring a state-run service is peanuts compared to waging a war abroad. Many remain unconvinced about the mantra that economic competition drives up quality, when it is the professional standards of healthcare staff, including doctors, nurses and allied health professionals, which appear to be at the heart of quality. The debate we have just had about the mode of procurement in the NHS was not one any of us as such elected; in other words, it has no mandate. If the Conservatives and the right-wing media appear so pre-occupied about having a referendum next parliament on our membership of the EU, many are (rightly) asking why Ed Miliband cannot ask for a mandate to take sensible decisions about the nature of the NHS. It is a given that there will always be a proportion of services which are outsourced to the private sector, but the question should be ‘how much’. Whilst a full-blown privatisation of the NHS has not happened yet, we have not even had a discussion of how much of the NHS should be outsourced.

And anyway Labour has to ask what really concerns all voters? In Mid Staffs and Cumbria, it is reported that there have been concerns about patient safety, and it may be mere coincidence that Labour failed to convince the voters in both places in the local elections over their offerings. However, there is certainly a ‘debate to be had’, about whether “efficiency savings” in the NHS are justified to produce surpluses in the NHS which get ploughed back into the Treasury (and therefore might be used for international overseas aid rather than frontline care.) Labour equally seems unable to look another ‘white elephant’ in the eye. That is of course the concept of a NHS hospital going bust. Should a NHS Trust which is in financial difficulty be simply allowed to go insolvent after a period of administration, or should the State pump money into it to maintain a local service to people in the community? This requires a fundamental reappraisal of how important “solidarity” and “social democracy” are, in fact, to Labour, and whether it wishes to use its extensive brand loyalty to have a mature, if sobering, discussion of the extent to which it wishes to fund a SOCIALIST National Health Service. Whilst in extremis it can be argued that a nostalgic return to ‘The Spirit of ’45” is not attainable, and is the wrong solution for the wrong times, there is a genuine perception that Labour has lost sight of its founding values. And why has this not been addressed in focus groups? It is well known that, in marketing, if you ask the wrong questions, you ubiquitously get the wrong answers.

Labour needs a mandate to confront these issues. And it should not be afraid to look for a resounding mandate, either. Whilst it might stick its fingers in its ears, and claim it’s nothing to do with them (arguing instead for integrated, “whole person” care), unless these ideological issues are confronted, NHS policy will continue to go down a right-wing path. For example, there is not much further to see GP ‘businesses’ being offered by the private sector, and the NHS pays for them; in this model, GP ‘businesses’ could operate under a standard 5-year contract, using NHS branding, under a ‘franchising’ model like Subway. And “The Tony Blair Dictum” is far from resolved, although currently there are issues more worthy of ‘firefighting’ in service delivery, such as the fiasco over ‘1111’. Labour’s problem is that it does not see the NHS as a ‘vote winner’, in the same way it doesn’t see the plight of disabled citizens experiencing difficulty with their benefits or people feeling genuinely threatened by ‘the bedroom tax’ as a top priority. Whilst Labour is unable to prioritise its issues in a way to align its aspirations with the concerns of the general public, there is no way on Earth it can hope to govern a convincing majority. If Labour wishes to learn a really useful trick from marketing, it could no better than to look at the ‘GAP analysis’ – looking at what the current situation is, and what the expectations of people are, and thinking how to get to a position of what people want. If people actually want a socialist universal, comprehensive NHS, paid for not in a private insurance system, Labour can be expected to work hard for a mandate to deliver this. If it doesn’t, that’s another matter, and it can witter on about whole-person care to its heart’s content.

We've just had a huge debate about the NHS. It's just a pity that it's been the wrong one.

Think of how much time we’ve just all spent, in thinking about the way in which services will be mostly put out for competitive tendering in the National Health Service. One of the first rules in law is that you fight your battles to the hilt, but, at first, you pick the right battles first. This is precisely what Labour appears not to have done. When Harriet Harman recently said on Question Time that the Conservatives are definitely not ‘to be trusted with the NHS’, Harriet curiously did not refer to the battle and war just won by the Conservatives (and Liberal Democrats) over NHS procurement. And yet the public desperately want Labour to stand up for the NHS. One member even suggested that, if Labour gave its unequivocal backing for restoring the NHS, Labour could even find itself with a massive vote winner.

Labour is clearly going through policy strands with a fine tooth comb, looking at, for example, the way in which multinational companies might employ workers at below the national minimum wage; effectively, controlling immigration through a wage policy. It does not appear to have worked out unequivocally whether it would reduce the rate of VAT, meaning possibly that the state borrowing requirement would temporarily increase. But do you see what they all did there? For days, weeks, or even months, we have been subjected to a relentless debate about EU immigration, when most surveys probably place the issue at number ten on the list of voters’ concerns. Unsurprisingly, the economy remains in ‘pole position’, but the ability of Labour to turn the opinion of the public, particularly in the South of England, away from the idea that Labour is ‘fiscally incontinent’ remains unconvincing. Labour is still considered to be the “tax and spend” party, for example, and Miliband appears painfully aware of that. So, when it comes to policy, there seems to be an odd combination of Labour shooting itself in the foot, or completely picking the wrong battles. And then you add in a complete inability to look at elephants in the room. Labour, to state the obvious, has no ability to implement any of its policies, if it is unable to win a General Election, and the confidence of Labour to win an election on its own is reflected accurately in Lord Adonis promoting his book that ‘if he were to form a new Lib-Lab pact, he wouldn’t start from here.‘

The NHS remains pivotal in Labour’s electoral chances, and Labour has been unable to use the resentment over the section 75 NHS regulations to maximise political capital. Why this should have happened in itself is interesting, as Andy Burnham, MP for Leigh, is a more than capable Shadow Secretary of State for Health. One of the issues is an ability to choose the right battle, possibly. Burnham, with some support from the right-wing media and thinktanks, has been banging on about integrated and whole-person care. Whether through conspiracy or cock-up, there will be short-term interest in how integrated care might be delivered. Think about a justification for State spending in the ‘mission impossible’ of implementing a NHS IT system. Why on earth would a right-wing libertarian government promote something which is national? Why on earth should you abort an ethos of ‘bonfire of the QUANGOs’ to introduce the biggest QUANGO in the country, viz NHS England? Whether you’re into conspiracy or cock-up, the integration of financial and medical information (including mental, physical and social care systems) allows for the perfect infrastructure for an insurance-based system. Insurance works on the basis of misrepresentation or non-disclosure to invalidate claims, so ‘big data’ serve a perfect storm for this. It won’t have escaped anybody’s attention that Labour (as indeed the Conservative Party) has been heading towards an insurance-based system for social care, so it does not require a massive ideological leap to think how this could be extended for all care with time. This does not involve any degree of paranoia, please note.

There is overwhelmingly an intellectual depravity in the bereft notion of producing policy through poll results and focus groups. New Labour clearly loved focus groups, with Philip Gould in ‘The Unfinished Revolution’ having devoted much airspace to developing a product in line with customers’ wishes. Of course, the Conservatives have a special affinity for polling organisations themselves, Nadhim Zadawi, in 2000 he co-founded YouGov and on its flotation became its CEO. YouGov is now one of the world leaders in political and business information gathering, polling and analysis. It employs over 400 staff on three continents and is listed on the London Stock Exchange. Again – it begs the question on why should Labour should wish to outdo the Conservatives on its own ability to use polling data? One of the polls which has become a toxic meme is how a high proportion of all voters would not mind who provides the NHS services, as long as it’s free at the point of use. However, this is intrinsically linked to other questions. Would you be prepared more in national insurance if it meant the NHS were able to provide a more comprehensive (universal) service?

It is indeed correct to state that the costs of renationalising the NHS might be overwhelming, although no accurate costings of this have ever been discussed properly. We do know, however, that the current cost of the NHS reorganisation is in the region of £3bn, but estimates of the actual cost inevitably have to be taken with a pinch of salt, as say the cost of Margaret Thatcher’s funeral. But to use this issue as a wish to stop discussion of this area is lazy, as one of the issues, as indeed as with Thatcher’s funeral, is that is this a sensible use of money compared to how it could be used elsewhere (so called “opportunity cost“)? Some people argue that the marketisation of the NHS has failed, in that any money spent on restoring a state-funded NHS would be money well spent. Restoring a state-funded service would get out of the idea of private companies being driven by maximising their profit margin, and not running a ‘more for less’ approach for delivering a service. Cynics might argue that the cost of restoring a state-run service is peanuts compared to waging a war abroad. Many remain unconvinced about the mantra that economic competition drives up quality, when it is the professional standards of healthcare staff, including doctors, nurses and allied health professionals, which appear to be at the heart of quality. The debate we have just had about the mode of procurement in the NHS was not one any of us as such elected; in other words, it has no mandate. If the Conservatives and the right-wing media appear so pre-occupied about having a referendum next parliament on our membership of the EU, many are (rightly) asking why Ed Miliband cannot ask for a mandate to take sensible decisions about the nature of the NHS. It is a given that there will always be a proportion of services which are outsourced to the private sector, but the question should be ‘how much’. Whilst a full-blown privatisation of the NHS has not happened yet, we have not even had a discussion of how much of the NHS should be outsourced.

And anyway Labour has to ask what really concerns all voters? In Mid Staffs and Cumbria, it is reported that there have been concerns about patient safety, and it may be mere coincidence that Labour failed to convince the voters in both places in the local elections over their offerings. However, there is certainly a ‘debate to be had’, about whether “efficiency savings” in the NHS are justified to produce surpluses in the NHS which get ploughed back into the Treasury (and therefore might be used for international overseas aid rather than frontline care.) Labour equally seems unable to look another ‘white elephant’ in the eye. That is of course the concept of a NHS hospital going bust. Should a NHS Trust which is in financial difficulty be simply allowed to go insolvent after a period of administration, or should the State pump money into it to maintain a local service to people in the community? This requires a fundamental reappraisal of how important “solidarity” and “social democracy” are, in fact, to Labour, and whether it wishes to use its extensive brand loyalty to have a mature, if sobering, discussion of the extent to which it wishes to fund a SOCIALIST National Health Service. Whilst in extremis it can be argued that a nostalgic return to ‘The Spirit of ’45” is not attainable, and is the wrong solution for the wrong times, there is a genuine perception that Labour has lost sight of its founding values. And why has this not been addressed in focus groups? It is well known that, in marketing, if you ask the wrong questions, you ubiquitously get the wrong answers.

Labour needs a mandate to confront these issues. And it should not be afraid to look for a resounding mandate, either. Whilst it might stick its fingers in its ears, and claim it’s nothing to do with them (arguing instead for integrated, “whole person” care), unless these ideological issues are confronted, NHS policy will continue to go down a right-wing path. For example, there is not much further to see GP ‘businesses’ being offered by the private sector, and the NHS pays for them; in this model, GP ‘businesses’ could operate under a standard 5-year contract, using NHS branding, under a ‘franchising’ model like Subway. And “The Tony Blair Dictum” is far from resolved, although currently there are issues more worthy of ‘firefighting’ in service delivery, such as the fiasco over ‘1111’. Labour’s problem is that it does not see the NHS as a ‘vote winner’, in the same way it doesn’t see the plight of disabled citizens experiencing difficulty with their benefits or people feeling genuinely threatened by ‘the bedroom tax’ as a top priority. Whilst Labour is unable to prioritise its issues in a way to align its aspirations with the concerns of the general public, there is no way on Earth it can hope to govern a convincing majority. If Labour wishes to learn a really useful trick from marketing, it could no better than to look at the ‘GAP analysis’ – looking at what the current situation is, and what the expectations of people are, and thinking how to get to a position of what people want. If people actually want a socialist universal, comprehensive NHS, paid for not in a private insurance system, Labour can be expected to work hard for a mandate to deliver this. If it doesn’t, that’s another matter, and it can witter on about whole-person care to its heart’s content.

Is the pilot always to blame if things go wrong in a safety-compliant plane in the NHS?

The “purpose” of an air plane crash investigation is apparently as set out in the tweet below:

It seems appropriate to extend the “lessons from the aviation industry” in approaching the issue of how to approach blame and patient safety in the NHS. Dr Kevin Fong, NHS consultant at UCHL NHS Foundation Trust in anaesthetics amongst many other specialties, highlighted this week in his excellent BBC Horizon programme how an abnormal cognitive reaction to failure can often make management of patient safety issues in real time more difficult. Approaches to management in the real world have long made the distinction between “managers” and “leaders” and it is useful to consider what the rôle of both types of NHS employees might be, particularly given the political drive for ‘better leadership’ in the NHS.

In corporates, reasons for ‘denial about failure’ are well established (e.g. Richard Farson and Ralph Keyes writing in the Harvard Business Review, August 2002):

“While companies are beginning to accept the value of failure in the abstract-at the level of corporate policies, processes, and practices-it’s an entirely different matter at the personal level. Everyone hates to fail. We assume, rationally or not, that we’ll suffer embarrassment and a loss of esteem and stature. And nowhere is the fear of failure more intense and debilitating than in the competitive world of business, where a mistake can mean losing a bonus, a promotion, or even a job.”

Farson and Keyes (2011) identify early-on for potential benefits of “failure-tolerant leaders”:

“Of course, there are failures and there are failures. Some mistakes are lethal-producing and marketing a dysfunctional car tire, for example. At no time can management be casual about issues of health and safety. But encouraging failure doesn’t mean abandoning supervision, quality control, or respect for sound practices, just the opposite. Managing for failure requires executives to be more engaged, not less. Although mistakes are inevitable when launching innovation initiatives, management cannot abdicate its responsibility to assess the nature of the failures. Some are excusable errors; others are simply the result of sloppiness. Those willing to take a close look at what happened and why can usually tell the difference. Failure-tolerant leaders identify excusable mistakes and approach them as outcomes to be examined, understood, and built upon. They often ask simple but illuminating questions when a project falls short of its goals:

- Was the project designed conscientiously, or was it carelessly organized?

- Could the failure have been prevented with more thorough research or consultation?

- Was the project a collaborative process, or did those involved resist useful input from colleagues or fail to inform interested parties of their progress?

- Did the project remain true to its goals, or did it appear to be driven solely by personal interests?

- Were projections of risks, costs, and timing honest or deceptive?

- Were the same mistakes made repeatedly?”

It is incredibly difficult to identify who is ‘accountable’ or ‘responsible’ for potential failures in patient safety in the NHS: is it David Nicholson, as widely discussed, or any of the Secretaries of States for health? There is a mentality in the popular media to try to find someone who is responsible for this policy, and potentially the need to attach blame can be a barrier to learning from failure. For example, Amy C Edmondson also in the Harvard Business Review writes:

“The wisdom of learning from failure is incontrovertible. Yet organizations that do it well are extraordinarily rare. This gap is not due to a lack of commitment to learning. Managers in the vast majority of enterprises that I have studied over the past 20 years—pharmaceutical, financial services, product design, telecommunications, and construction companies, hospitals, and NASA’s space shuttle program, among others—genuinely wanted to help their organizations learn from failures to improve future performance. In some cases they and their teams had devoted many hours to after-action reviews, post mortems, and the like. But time after time I saw that these painstaking efforts led to no real change. The reason: Those managers were thinking about failure the wrong way.”

Learning from failure is of course extremely important in the corporate sectors, and some of the lessons might be productively transposed to the NHS too. This is from the same article:

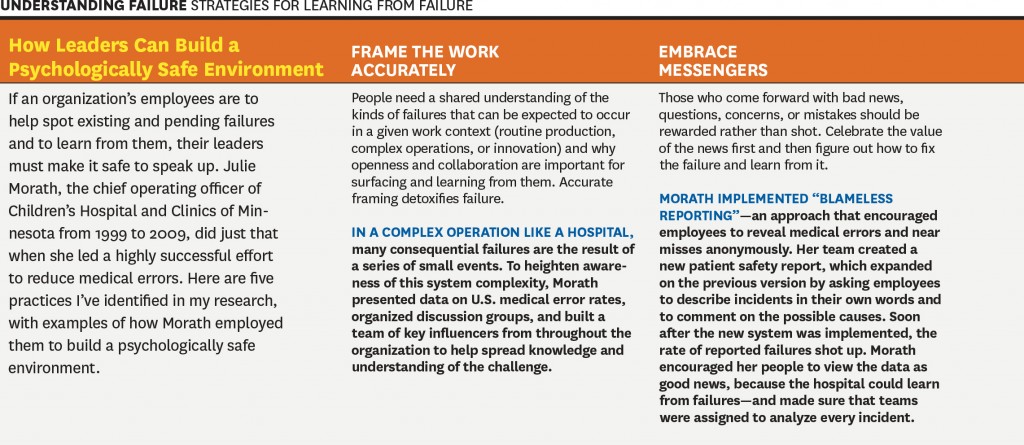

However, is this is a cultural issue or a leadership issue? Michael Leonard and Allan Frankel in an excellent “thought paper” from the Health Foundation begin to address this issue:

“A robust safety culture is the combination of attitudes and behaviours that best manages the inevitable dangers created when humans, who are inherently fallible, work in extraordinarily complex environments. The combination, epitomised by healthcare, is a lethal brew.

Great leaders know how to wield attitudinal and behavioural norms to best protect against these risks. These include: 1) psychological safety that ensures speaking up is not associated with being perceived as ignorant, incompetent, critical or disruptive (leaders must create an environment where no one is hesitant to voice a concern and caregivers know that they will be treated with respect when they do); 2) organisational fairness, where caregivers know that they are accountable for being capable, conscientious and not engaging in unsafe behaviour, but are not held accountable for system failures; and 3) a learning system where engaged leaders hear patients and front-line caregivers’ concerns regarding defects that interfere with the delivery of safe care, and promote improvement to increase safety and reduce waste. Leaders are the keepers and guardians of these attitudinal norms and the learning system.”

Whatever the debate about which measure accurately describes mortality in the NHS, it is clear that there is potentially an issue in some NHS trusts on a case-by-case issue (see for example this transcript of “File on 4″‘s “Dangerous hospitals”), prompting further investigation through Sir Bruce Keogh’s “hit list“) Whilst headlines stating dramatic statistics are definitely unhelpful, such as “Another nine hospital trusts with suspiciously high death rates are to be investigated, it was revealed today”, there is definitely something to investigate here.

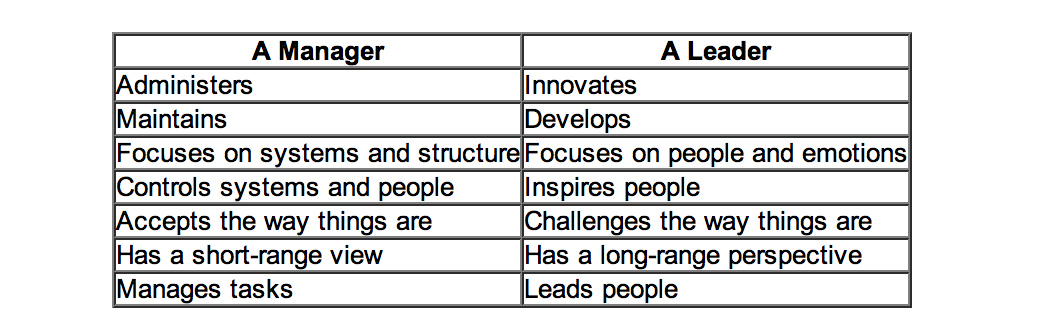

Is this even a leadership or management thing? One of the most famous distinctions between managers and leaders was made by Warren Bennis, a professor at the University of Southern California. Bennis famously believes that, “Managers do things right but leaders do the right things”. It is argued that doing the right thing, however, is a much more philosophical concept and makes us think about the future, about vision and dreams: this is a trait of a leader. Bennis goes on to compare these thoughts in more detail, the table below is based on his work:

Differences between managers and leaders

Indeed, people are currently scrabbling around now for “A new style of leadership for the NHS” as described in this Guardian article here.

Is patient safety predominantly a question of “teamwork”?

Amalberti and colleagues (Amalberti et al., 2005) make some interesting observations about teamwork and professionalism:

“A growing movement toward educating health care professionals in teamwork and strict regulations have reduced the autonomy of health care professionals and thereby improved safety in health care. But the barrier of too much autonomy cannot be overcome completely when teamwork must extend across departments or geographic areas, such as among hospital wards or departments. For example, unforeseen personal or technical circumstances sometimes cause a surgery to start and end well beyond schedule. The operating room may be organized in teams to face such a change in plan, but the ward awaiting the patient’s return is not part of the team and may be unprepared. The surgeon and the anesthesiologist must adopt a much broader representation of the system that includes anticipation of problems for others and moderation of goals, among other factors. Systemic thinking and anticipation of the consequences of processes across depart- ments remain a major challenge.”

Weisner and colleagues (Weisner et al., 2010) have indeed observed that:

“Medical teams are generally autocratic, with even more extreme authority gradient in some developing countries, so there is little opportunity for error catching due to cross-check. A checklist is ‘a formal list used to identify, schedule, compare or verify a group of elements or… used as a visual or oral aid that enables the user to overcome the limitations of short-term human memory’. The use of checklists in health care is increasingly common. One of the first widely publicized checklists was for the insertion of central venous catheters. This checklist, in addition to other team-building exercises, helped significantly decrease the central line infection rate per 1000 catheter days from 2.7 at baseline to zero.”

M. van Beuzekom and colleagues (van Beuzekom et al., 2013) and colleagues, additionally, describe an interesting example from the Netherlands. Teams in healthcare are co-incidentally formed, similar to airline crews. The teams consist of members of several different disciplines that work together for that particular operation or the whole operating day. This task-oriented team model with high levels of specialization has historically focused on technical expertise and performance of members with little emphasis on interpersonal behaviour and teamwork. In this model, communication is informally learned and developed with experience. This places a substantial demand on the non-clinical skills of the team members, especially in high-demand situations like crises.

Bleetman and colleagues (Bleetman et al., 2011) mention that, “whenever aviation is cited as an example of effective team management to the healthcare audience, there is an almost audible sigh.” Debriefing is the final teamwork behaviour that closes the loop and facilitates both teamwork and learning. Sustaining these team behaviours depends on the ability to capture information from front-line caregivers and take action. In aviation, briefings are a ‘must-do’ are not an optional extra. They are performed before every take-off and every landing. They serve to share the plan for what should happen, what could happen, to distribute the workload efficiently and to prevent and manage unexpected problems. So how could we fit briefings into emergency medicine? Even though staff may be reluctant to leave the computer screen in a busy department, it is likely to be worth assembling the team for a few minutes to provide some order and structure to a busy department and plan the shift.

Briefing points apparently could cover:

- The current situation

- Who is present on the team and their experience level

- Who is best suited to which patients and crises so that the most effective deployment of team members occurs rathe than a haphazard arrangement

- The identification of possible traps and hazards such as staff shortages ahead of time

- Shared opinions and concerns.

The authors describe that, “at the end of the shift a short debriefing is useful to thank staff and identify what went well and what did not. Positive outcomes and initiatives can be agreed.”

Is patient safety predominantly a question of “leadership”?

The literature identifies that overall team members are important who have a good sense of “situational awareness” about the patient safety issue evolving around them. However, it is being increasingly recognised that to provide effective clinical leadership in such situations, the “team leader” needs to develop a certain set of non-clinical skills. This situation demands more than currency in advance paediatric life support or advanced trauma life support; it requires the confidence (underpinned by clinical knowledge) to guide, lead and assimilate information from multiple sources to make quick and sound decisions. The team leader is bound to encounter different personalities, seniority, expectations and behaviours from members of the team, each of whom will have their own insecurities, personality, anxieties and ego.

Amalberti and colleagues (Amalberti et al., 2005) begin to develop a complex narrative on the relationship between leadership and management (and the patients whom “they serve”):

“Systems have a definite tendency toward constraint. For example, civil aviation restricts pilots in terms of the type of plane they may fly, limits operations on the basis of traffic and weather conditions, and maintains a list of the minimum equipment required before an aircraft can fly. Line pilots are not allowed to exceed these limits even when they are trained and competent. Hence, the flight (product) offered to the client is safe, but it is also often delayed, rerouted, or cancelled. Would health care and patients be willing to follow this trend and reject a surgical procedure under circumstances in which the risks are outside the boundaries of safety? Physicians already accept individual limits on the scope of their maximum performance in the privileging process; societal demand, workforce strategies, and competing demands on leadership will undermine this goal. A hard-line policy may conflict with ethical guidelines that recommend trying all possible measures to save individual patients.”

Conclusion

Even if one decides to blame the pilot of the plane, one has to wonder the extent to which the CEO of the entire airplane organisation might to be blame. The question for the NHS has become: who exactly is the pilot of plane? Is it the CEO of the NHS Foundation Trust, the CEO of NHS England, or even someone else? And rumbling on in this debate is whether the plane has definitely crashed: some relatives of passengers are overall in absolutely no doubt that the plane has crashed, and they indeed have to live with the wreckage daily. Politicians have then to decide whether the pilot ought to resign (has he done something fundamentally wrong?) or has there been something fundamentally much more distal which has gone wrong with his cockpit crew for example? And, whichever figurehead is identified if at all for any problems in this particular flights, should the figurehead be encouraged to work in a culture where problems in flying his plane have been identified and corrected safely? And finally is this is a lone airplane which has crashed (or not crashed), and are there other reports of plane crashes or near-misses to come?

References

Learning from failure

Farson, R. and Keyes, R. (2002) The Failure Tolerant Leader, Harvard Bus Rev, 80(8):64-71, 148.

Edmondson, A. Strategies for learning from failure, Harvard Bus Rev, ;89(4):48-55, 137.

Patient safety

Amalbert, R., Auroy, Y., Berwick, D., and Barach, P. (2005) Five System Barriers to Achieving Ultrasafe Health Care, Ann Intern Med, 142, pp. 756-764.

Bleetman, A., Sanusi, S., Dale, T., and Brace, S.(2012) Human factors and error prevention in emergency medicine, Emerg Med J, 29, pp. 389e393. d

Federal Aviation Administration, Section 12: Aircraft Checklists for 14 CFR Parts 121/135 iFOFSIMSF.

Pronovost, P., Needham, D., Berenholtz, S., Sinopoli, D., Chu, H., Cosgrove, S., Sexton, B., Hyzy, R., Welsh, R., Roth, G., Bander, J., Kepros, J., and Goeschel, C. (2006) An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU, N Engl J Med, 355, pp. 2725–32.

van Beuzekom, M., Boer, F., Akerboom, S., and Dahan, A. (2013) Perception of patient safety differs by clinical area and discipline, British Journal of Anaesthesia, 110 (1), pp. 107–14.

Weisner, T.G., Haynes, A.B., Lashoher, A., Dziekman, G., Moorman, D.J., Berry, W.R., and Gawande, A.A. (2010) Perspectives in quality: designing the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 22(5), pp. 365–370.

Andy Burnham's "whole-person care" could be visionary, or it could be "motherhood and apple pie"

“Whole-Person Care” was at the heart of the proposal at the heart of Labour’s health and care policy review, formally launched yesterday, and presents a formidable task: a new “Burnham Challenge”?

It is described as follows:

“Whole-Person Care is a vision for a truly integrated service not just battling disease and infirmity but able to aspire to give all people a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being. A people-centred service which starts with people’s lives, their hopes and dreams, and builds out from there, strengthening and extending the NHS in the 21st century not whittling it away.”

Andy Burnham did not mention the Conservatives once in his speech yesterday for the King’s Fund, the leading think-tank for evidence-based healthcare policy. He did not even produce any unsolicited attacks on the private sector, but this entirely consistent with a “One Nation” philosophy. Burnham was opening Labour’s health and care policy review, set to continue with the work led by Liz Kendall and Diane Abbott. He promised his starting point was “from first principles”, and “whatever your political views, it’s a big moment. However, he faces an enormous task in formulating a coherent strategy acknowledging opportunities and threats in the future, particularly since he suffers from lack of uncertainty about the decisions on which his health team will form their decisions: the so-called “bounded rationality”. The future of the NHS is as defining a moment as a potential referendum on Europe, and yet the former did not attract attention from the mainstream media.

Burnham clearly does not have the energy for the NHS to undergo yet another ‘top down reorganisation’, when the current one is estimated as costing £3bn and causing much upheaval. He indeed advanced an elegant argument that he would be seeking an organisational cultural change itself, which is of course possible with existant structures. This lack of cultural change, many believe, will be the primary source of failure of the present reorganisation. He was clear that competition and the markets were not a solution.

Burnham identifies the societal need to pay for social care as an overriding interest of policy. This comes back to the funding discussion initiated by Andrew Dilnot prior to this reorganisation which had been kicked into the ‘long grass’. Many younger adults do not understand how elderly social care is funded, and the debate about whether this could be a compulsory national insurance scheme or a voluntary system is a practical one. It has been well rehearsed by many other jurisdictions, differing in politics, average income and competence of state provision. The arguments about whether a voluntary system would distort the market adversely through moral hazard and loss aversion are equally well rehearsed. Whilst “the ageing population” is not the sole reason for the increasing funding demands of all types of medical care, it is indeed appropriate that Burnham’s team should confront this issue head-on.

It is impossible to escape the impact of health inequalities in determining a society’s need for resources in any type of health care. Burnham unsurprisingly therefore suggested primary health and preventative medicine being at the heart of the new strategy, and of course there is nothing particularly new in that, having been implemented by Ken Clarke in “The Health of the Nation” in the 1980s Conservative government. General medical physicians including General Practitioners already routinely generate a “problem” list where they view the patient as a “whole”; much of their patient care is indeed concerned with preventive measures (such as cholesterol management in coronary artery disease). A patient with rheumatoid disease might have physical problems due to arthritis, emotional problems related to the condition or medication, or social care problems impeding independent living. Or a person may have a plethora of different physical medical, mental health or social needs. The current problem is that training and delivery of physical medical, mental health or social care is delivered in operational silos, reflecting the distinct training routes of all disciplines. As before, the cultural change management challenge for Burnham’s team is formidable. Also, if Burnham is indeed serious about “one budget”, integrating the budgets will be an incredible ambitious challenge, particularly if the emphasis is person-centred preventive spending as well as patient-centred problem solving spending. When you then consider this may require potential aligment of national and private insurance systems, it gets even more complicated.

The policy proposed by Burnham interestingly shifts emphasis from Foundation Trusts back to DGHs which had been facing a challenge to their existence. Burnham offers a vision for DGHs in coordinating the needs of persons in the community. Health and Well-Being Boards could come to the fore, with CCGs supporting them with technical advice. A less clear role for the CCGs as the statutory insurance schemes could markedly slow down the working up of the NHS for a wholesale privatisation in future, and this is very noteworthy. Burnham clearly has the imperfect competition between AQPs in his sights. Burnham is clearly also concerned about a fragmented service which might be delivered by the current reforms, as has been previously demonstrated in private utilities and railways which offer disproportionate shareholder value compared to end-user value as a result of monopolistic-type competition.

The analysis offered by Andy Burnham and the Shadow Health team is a reasonable one, which is proposed ‘in the national interest’. It indeed draws on many threads in domestic and global healthcare circles. Like the debate over EU membership, it offers potentially “motherhood” and “apple pie” in that few can disagree with the overall goals of the policy, but the hard decisions about how it will be implemented will be tough. Along the way, it will be useful to analyse critical near-gospel suggestions that competition improves quality in healthcare markets, if these turn out to be “bunkum”.Should there be a national compulsory insurance for social care? How can a near-monopolistic market in AQPs be prevented?

The "everyday" "stack-em-high" culture clearly doesn't work for all of the NHS

Right-wing commentators always attack the NHS by saying that it mustn’t be treated as a “sacred cow”, like a “national religion”. The public don’t wish to see it as a business either. It is not surprising that the Royal College of Surgeons as a College are in favour of the “reforms” increasing the scope for private provision, but most surgeons were indeed also trained by the NHS.

So, if it’s not a business, why are they such pains to keep the NHS branding and logo then? The lettering (even the font, size, colour and slant) is known on the national trademarks register, so is the exact Pantone colour. Why are Virgin and Circle not keen to get rid of the NHS branding and do all their NHS services in their own brand? This is simple. It’s because the NHS brand is incredibly strong, so much so that successive governments have wished to export it.

Tesco everyday burgers contain “no artificial preservatives, flavours or colours”, except some contained horsemeat apparently. Not being able to see inside the box with the benefit of a DNA reader is possibly to blame, but which corporate supplier is providing your hernia operation in future may not be so easy to tell in future either.

One thing is absolutely certain about the NHS “reforms”. It is most definitely a “top-down reorganisation”, it will not address the numerous concerns of the Francis Report, and it gives a clear green light to outsourcing a far greater number of contracts to private sector suppliers who are very slick at producing bids. Even the most unintelligent of spokespeople for the Conservatives’ policy, both official and unofficial, openly concede that it is hard to provide a service that is comprehensive and bitty through this route.

That’s why it best for the profitability of shareholders that the product is delivered in a short-sharp-shock, like an abdominal hernia repair, or a Tesco “everyday burger” containing horsemeat. They choose what offerings they wish to produce. Whilst the Ed Miliband conference speech on ‘predators and producers’ was on-the-whole “panned”, the new healthcare market is perfect for private equity investors. Their freedom to operate in a “liberalised market” is only constrained by the legal and regulatory constraints placed upon them. You can argue “til the cows come” home whether the abolition of the Foods Standards Authority created a climate for such cutting corners to occur – or maybe that should be “til the horses come home”.

While it’s well known that some high street firms have struggled, it’s noticeable that “value brands”, including Tesco everyday value items and Aldi, and “luxury” brands have withstood the recession quite well. There is of course no real market in healthcare, of people “shopping around”, with a customer not paying directly to the supplier of the healthcare product, the supplier using the NHS branding away, and dodgy metrics to judge the ‘quality’ of a healthcare intervention largely dreamt up by a busybody who has never set foot on a busy NHS ward.

However, that the NHS could offer its equivalent of “value” products, but not to enhance shareholder dividend, but for the benefit of treating as many people as possible efficiently to the highest of rigorous medical and nursing standards is a worthy cause. An unfortunate effect of the reaction to the Tesco “horsemeat” saga is that rather demeaning judgements about people who buy “everyday” products have entered through the back door. However, many people are desperately keen to avoid an emergence of a “two tier” service in healthcare where access-to-medical-treatment becomes dependent upon an ability-to-pay.

It’s possible that at the “everyday” end of the NHS, it might be possible to go for the “stack them high” approach which is pervading education and healthcare, which is perfect for private equity investors. However, this system is clearly not ideal for all, and this is clear not a market led by the “end-consumer”. Characteristics of markets where there is poor competition due to lack of participants include an inability of customers to lower prices and an ability for suppliers to increase prices, while providing the essentially the same product. This is what has happened in a whole string of privatised industries, including gas, electricity, water and railways, and the (relatively) “simple” hernia operation is going to be no different. Whose going to benefit from offering a contracted core NHS service? Of course, the corporates whom I don’t dare to name because of their legal teams. Will the patient benefit compared to a NHS ideal of “comprehensive” and “free-at-the-point-of-use”? Absolutely not.

The “Everyday” “stack-em-high” culture clearly doesn’t work for all of the NHS

Right-wing commentators always attack the NHS by saying that it mustn’t be treated as a “sacred cow”, like a “national religion”. The public don’t wish to see it as a business either. It is not surprising that the Royal College of Surgeons as a College are in favour of the “reforms” increasing the scope for private provision, but most surgeons were indeed also trained by the NHS.

So, if it’s not a business, why are they such pains to keep the NHS branding and logo then? The lettering (even the font, size, colour and slant) is known on the national trademarks register, so is the exact Pantone colour. Why are Virgin and Circle not keen to get rid of the NHS branding and do all their NHS services in their own brand? This is simple. It’s because the NHS brand is incredibly strong, so much so that successive governments have wished to export it.

Tesco everyday burgers contain “no artificial preservatives, flavours or colours”, except some contained horsemeat apparently. Not being able to see inside the box with the benefit of a DNA reader is possibly to blame, but which corporate supplier is providing your hernia operation in future may not be so easy to tell in future either.

One thing is absolutely certain about the NHS “reforms”. It is most definitely a “top-down reorganisation”, it will not address the numerous concerns of the Francis Report, and it gives a clear green light to outsourcing a far greater number of contracts to private sector suppliers who are very slick at producing bids. Even the most unintelligent of spokespeople for the Conservatives’ policy, both official and unofficial, openly concede that it is hard to provide a service that is comprehensive and bitty through this route.

That’s why it best for the profitability of shareholders that the product is delivered in a short-sharp-shock, like an abdominal hernia repair, or a Tesco “everyday burger” containing horsemeat. They choose what offerings they wish to produce. Whilst the Ed Miliband conference speech on ‘predators and producers’ was on-the-whole “panned”, the new healthcare market is perfect for private equity investors. Their freedom to operate in a “liberalised market” is only constrained by the legal and regulatory constraints placed upon them. You can argue “til the cows come” home whether the abolition of the Foods Standards Authority created a climate for such cutting corners to occur – or maybe that should be “til the horses come home”.

While it’s well known that some high street firms have struggled, it’s noticeable that “value brands”, including Tesco everyday value items and Aldi, and “luxury” brands have withstood the recession quite well. There is of course no real market in healthcare, of people “shopping around”, with a customer not paying directly to the supplier of the healthcare product, and the supplier using the NHS branding away, dodgy metrics to judge the ‘quality’ of a healthcare intervention largely dreamt up by a busybody who has never set foot on a busy NHS ward.

However, that the NHS could offer its equivalent of “value” products, but not to enhance shareholder dividend, but for the benefit of treating as many people as possible efficiently to the highest of rigorous medical and nursing standards is a worthy cause. An unfortunate effect of the reaction to the Tesco “horsemeat” saga is that rather demeaning judgements about people who buy “everyday” products have entered through the back door. However, many people are desperately keen to avoid an emergence of a “two tier” service in healthcare where access-to-medical-treatment becomes dependent upon an ability-to-pay.

It’s possible that at the “everyday” end of the NHS, it might be possible to go for the “stack them high” approach which is pervading education and healthcare, which is perfect for private equity investors. However, this system is clearly not ideal for all, and this is clear not a market led by the end-“consumer”. Characteristics of markets where there is poor competition due to lack of participants include an inability of customers to lower prices and an ability for suppliers to increase prices, while providing the essentially the same product. This is what has happened in a whole string of privatised industries, including gas, electricity, water and railways, and the (relatively) “simple” hernia operation is going to be no different. Whose going to benefit from offering a contracted core NHS service? Of course, the corporates whom I don’t dare to name because of their legal teams. Will the patient benefit compared to a NHS ideal of “comprehensive” and “free-at-the-point-of-use”? Absolutely not.

Integration in healthcare: a personal view

I feel that there is a lot of “hype” concerning integration of health and social care services, and I do not wish to reinvent the wheel by offering the same definitions and the same process maps.

However, I think the challenge is at a number of different levels. First of all, I think that there needs to be a cultural change whereby the medical and social care cultures meet somewhere. Moving towards a culture where the health and social care needs, both medical and welfare, meet requires some understanding of why and how the cultures are different. There are a number of contributing factors, but it is hard to escape from the inherent difference in organizational structures and functions, personnel, training, budgets, to name but a few. Again, this brings up the problem of the extent to which managers can manage in the NHS without direct experience of how patients are clinically managed in the NHS.

Secondly, there is no doubt that logistically a NHS, fit for purpose, faces a massive task in being operationally ‘fit for purpose’. We all know about the disaster which was the NHS IT project, but certainly we need a health service where exchange of information between hospitals and primary care, and other institutions, needs to be much more easily achieved, and serious consideration to be given how much (if all) of it is to be shared with the patient himself or herself.

I personally don’t wish to move to a world where patients are somehow incentivized to receive the cheapest possible healthcare at the expense of quality, so I think it’s really important that integration is not used to ‘sell’ healthcare from suppliers to the patient in an unnecessary way, either directly or indirectly. I think it is necessary to have a discussion of how a complex patient with multiple needs is best served by a range of medical and other healthcare professionals, but I am mindful of entering into this discussion at the end of a traumatic £3bn organization. If there is to be a realistic chance of producing a cultural change towards integration at all, it is imperative that we do not repeat the same mistakes which threaten to engulf the NHS reorganisation just enacted. To ignore the principal stakeholders (NOT the private healthcare companies BUT the BMA, RCN and other medical colleges) would produce yet another catastrophe, however planning goes into this from thinktanks or management consultants.