Home » Rationing treatment

A personal budget approach blind to the underlying neuroscience of dementia is doomed to failure

One of the critical messages in recent public health awareness campaigns about dementia is that there is much more to a person living with dementia than his or her actual diagnosis. This focus on personhood, how the person living with dementia understands himself or herself, in the context of his past, present and relationships, and in relation to his or her own environment, is of course critical. It is likely to be embraced in the overall approach of whole person care in this jurisdiction.

Much of the current policy in England in dementia is driven by a scant existence of relevant evidence, for example the mental distress and lack of appropriate management caused by false diagnoses of dementia not confirmed elsewhere in the system. For example, even in the eight years since the seminal paper by Gail Mountain in the journal ‘Dementia’ in 2006, we have had little progress in the literature on the extent to which people at various stages of different types of dementia are able to manage, or want to manage, their own conditions, depending on their cognitive, affective or motivational abilities. This blogpost is about the form of personal budgets where people with dementia are given the money directly to spend, without any broker.

Likewise, the approach of personal budgets in dementia has equal scant regard to an approach necessitated by the cognitive neuroscience. Being able to operate a budget is likely to require a good understanding of mathematics; and it has been known for decades, or if not centuries, that people with disruption of the functioning of a part of the brain known as the parietal cortex can have problems with calculations. This is called ‘dyscalculia’.

Some people with dementia might have real problems in anticipating future outcomes (as shown in the famous Anderson paper) or have problems in making accurate cognitive estimates (as discussed in the famous paper by Shallice and Burgess). The people with dementia for whom these problems are likely to surface are those with disruption of the functioning of a part of the brain known as the frontal lobe.

Also, I showed myself in 1999, published in Brain, that people in early stages of behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia can be prone to make risky decisions. Others have argued it is more of a problem with impulsivity.

Nobody has any intention of turning people living with early stages of dementia into amateur accountants, but even with the basic budgets you need to have an ability to deal with income, expenditure, costing and reasonable forecasting.

So there is clearly an evidence base emerging that, despite full legal capacity, there are some persons living with dementia who are best not served by direct payments so that they can pursue their ‘choice’. But the introduction of this has been surreptitious, couched in language such as “empowering people with dementia to take control of their own risk behaviour.”

Such flowery language is best kept in marketing manuals, I feel. At a time when report after report has demonstrated that there is not a strong evidence base for improvement in clinical outcomes (such as falls for people with dementia), we must be able to ask for whose benefit are these self-directed budgets for people with dementia?

There is report after report of ‘widening the market’, complaining about the lack of quality ‘control’ of market offerings for dementia. And yet we simultaneously have a care regulator complaining regularly about the quality of dementia services in trusts in England. We have a poor evidence base on what level of budget is sufficient to allow a choice; clearly someone who has an insufficient budget cannot find a choice argument at all compelling.

And is the quality of market offerings being properly regulated to prevent fraud? The last few years has witnessed a series of seemingly attractive offerings for living well with dementia, some of which are extremely good (such as assistive technology, better design of wards and the home), and some of which are poor. There is insufficient evidence here too that the regulator is able to cope confidently except in the clearest examples of fraud.

There is much good work being done in social care and medicine, but with a drive for shiny, instant products, we must never lose sight of the fact that care from social care has been cut consistently over a long period of time. Whenever someone explains the case for personal budgets, there is almost certainly a concomitant explanation of an exploding care budget. However, it would be wrong to slash frontline care while touting ‘The Big Society’ in the same way it would be completely wrong to cut in real terms per caput allocations of care or to pursue backdoor rationing in the name of choice.

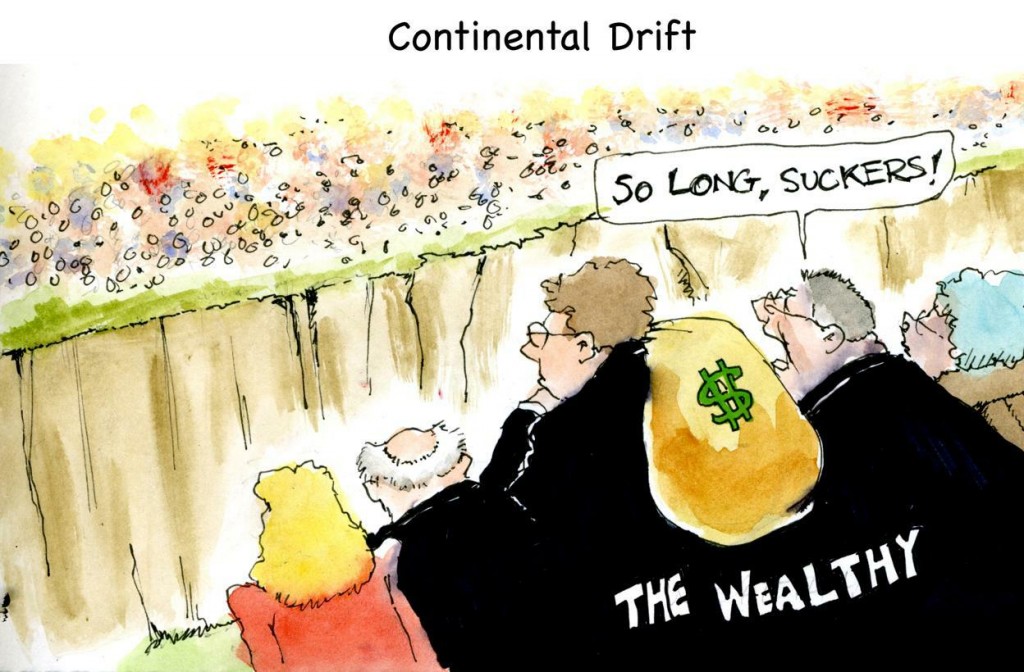

Some should be very afraid of Thomas Piketty. We may not be all customers of the NHS now.

Let me buy into the ‘Piketty bubble‘ momentarily, in a tenuous discussion of his book ‘Capitalism in the 21st century’ in relation to the National Health Service.

Since the 1980s, a change in terminology began in England.

Patients in the National Health Service became increasingly known as ‘users’, or as ‘customers’. Throw forwards to 2014, and Chuka Umunna in the UK Labour Party proudly boasts ‘we are all capitalists now’.

Cynics might argue that ‘bringing the lowest out of the poverty’ makes everyone into a capitalist, but I probably wouldn’t talk in such strong terms.

There is a clearly a huge public appetite for a frank discussion on ‘inequality’, on how wealth can be accumulated in the very few and how the super-rich are growing ever distant from those of the bottom of the wealth scale.

Piketty argues that for ‘disruptive’ super events such as the Great Depression or World Wars, inequality would have got far worse.

The most solid part of Piketty’s narrative, as I am sure the author himself would himself concede, is the historical part reviewing what happened in the 19th Century.

And yet, even if the super-élite such as Lord Stewart Wood and Tim Livesey of Ed Miliband’s circle don’t want to buy into it public, a fairer re-distributive taxation system appears not to be on the cards.

Such a fair taxation system is the most parsimonious solution to the ‘funding gap’ presented before the NHS. But to the exasperation of right-wing think tanks the NHS ‘sustainability gap’ has been revealed finally as the Emperor’s New Clothes.

The NHS is a system packed full of brilliant minds but who are collectively underfunded.

And that’s also where the narrative of the right-wing think tanks also runs into problems. Much to the annoyance of the same right-wing think tanks, ‘patients’ have not been successfully rebranded as ‘customers’. We might not be all capitalists now.

In fact, it may be more specific than that. ‘Google’ is the new ‘essential utility company': are we all consumers of multinational corporates now?

And this matter creates a further important ideological discussion, reincarnated for modern times.

It was mooted only yesterday by Prime Minister David Cameron that Labour has resisted all successful transfers of resources into the private sector, such as British Telecom or Royal Mail.

Most members of the Coalition governing parties can bring themselves to mention the ‘P’ word with regards to the NHS, especially with the wealth of a few investors who have benefited handsomely from the initial public offering of the Royal Mail having gone up into the stratosphere.

But the idea of wealth being concentrated in the hands of the few private sector operators goes to the heart of the public displeasure of the outsourcing and privatisation of the NHS through the Health and Social Care Act (2012).

That’s because here it is a matter of life or death. In simple terms, nobody wants to live in a society where a child with a rare genetic disorder, such as juvenile metachromatic leukodystrophy, is denied a potentially life-saving treatment, such as bone marrow transplantation, because of an inability to pay.

This argument also reaches another level, when you consider that all the main political parties are gradually converging on the concept of unified personal budgets for health and social care. While ‘top up payments’ appear to have been ruled out, it is uncertain whether this pretence will be kept up for much longer.

Lord Norman Lamont, not known for his intellectual prowess, claimed last night in his skinny dipping into the Piketty bubble that the only way to achieve ‘equality of opportunity’ would be to abolish inheritance tax. This is clearly as ludicrous as saying that the only way to achieve ‘equality of opportunity’ for alternative qualified (private) providers, or economic parity, would be to abolish the NHS. Oh wait.

The promise that the NHS is free, comprehensive and free at the point of need may be in large part correct, but is clearly not wholly true if very expensive treatments, such as the breast cancer drug Kadcycla, are rationed.

Shareholders and directors of large organisations may have a rather different opinion from those carers on zero-hour contracts who literally don’t know whether they’re coming or going.

There is an economic distinction between the ‘inequality’ arguments and the ‘cost of living’ arguments, but the former may indeed more easily adaptable for Ed Miliband’s new political messaging guru David Axelrod.

In terms of the sheer politics, campaigning on inequalities in health service provision is a big win (or “low hanging fruit”); some other, albeit hugely important, public health topics less so.

Indeed, some should be very afraid of the translated Thomas Piketty narrative, not least certain prominent members of the main political parties.

Piketty has helped to show that economics is not a ‘dismal science’, but is profoundly relevant to our society.

And, for that reason alone, we may not be all customers of the NHS now.

The car crash interview of a Trustee of the King’s Fund about potential payments for the NHS

The political parties have two strands of consensus which at first blush may seem somewhat irreconcilable: a NHS which is universal, and free-at-the-point-of-need, and £15-20 ‘efficiency savings’ within the next few years.

Taxes could rise to increase the size of the public expenditure pot. thereby generating additional funds to flow into public funding for healthcare. There does not seem to be any political appetite for this approach at the moment. While technically possible (tax levels are far higher in Nordic countries than in the UK), this is unlikely to provide an answer in the short term.

The NHS is heading for a “breakdown” if people expect it carry on providing all services for free under increasing demand, the former head of Marie Curie Cancer Care has warned.

Sir Thomas Hughes-Hallett urged us to ‘take more responsibility’, encouraging us to think about what we ‘really need for free'; he gave his view of how to keep the NHS on the road, saying it should – like a a garage – charge “for extras”.

He said people “need a sat-nav” to point them what is “most convenient”, towards chemists or community support centres and “steer them away from the NHS when they don’t need it”.

He further added that people should treat their bodies like a car, with a regular MOT, and that “we need to take more responsibility for our own health”.

Hughes-Hallett, a trustee of the King’s Fund, and Executive Chair of the Institute of Global Health Innovation at Imperial College, London, predicted: “We need to make tough choices for now about what we really need for free”.

Unfortunately, Sir Thomas was a guest on Wednesday’s Daily Politics today, and his defence of his own argument was worse than pitiful as you can see here (at 1 hr 29 minutes).

Andrew Neil started the discussion by enquiring off Hughes-Hallett where he “would draw the line”, mooting gastric banding, acupuncture, and varicose veins.

For fertility treatment, he said: “there is no yes or no answer.”

Neil then replied that some difficult questions would have to be answered.

Alan Duncan MP said: “It’s free-at-the-point of need and that’s not going to change…. but for the mainstream medical needs, that’s not going to change.”

Vernon Coaker MP said: “This is the thin-end-of-the-wedge. The whole point of the NHS is that’s free-at-the-point-of-use, and if you start charging, you’re going to end up with a two tier service, and the poor will be disadvantaged.”

Hughes-Hallett claimed: “Many people are willing to pay.”

The NHS could start to draw in funds from other sources, such as co-payments and supplementary insurance. Again, these could potentially start to challenge existing views on equity, because they inevitably introduce an element of some kind of payment to access services. Exemptions and subsidies can mitigate this to some extent, but the more they are used, the more they offset the expenditure benefits of alternative sources of funding in the first place.

In a recent view, the departing CEO of NHS England said that the introduction of co-payments, imminently, was “unlikely”.

A question still remains over how to deal with services that fall outside the defined core package. If they are significant in the eyes of patients, markets will develop to cover those services, funded either through fee for service or insurance-based mechanisms.

On the one hand, the development of such a market might be regarded as undermining equity (some in society will be able to pay to access health services that are not freely available to all). Others will interpret it as a natural market response that is neither desirable nor sensible to prevent — what matters is ensuring that the core package of services that is available to all is adequate.

It cannot be denied, however, that a growing number of people feel that the marketisation of the NHS has gone far too far.

In fact, many want the market abolished altogether now.

Infertility treatment: when poor access-to-medicine to access-to-law come together

It is estimated that infertility affects 1 in 7 heterosexual couples in the UK. Since the original NICE guideline on fertility published in 2004 there has been a small increase in the prevalence of fertility problems, and a greater proportion of people now seeking help for such problems.

In a striking letter published on 18 June 2013 in the BMJ entitled, “NICE promises on infertility and caesarean section are unmet” from Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Hospital, Lawrence Mascarenhas (a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist), Zachary Nash (medical student), and Bassem Nathan (consultant surgeon), describe that NICE ‘promises on infertility and caesarean section are unmet’. Mr Mascharenhas and colleagues argue that “Current underfunding of the NHS means that some National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines are unachievable”. According to Matthew Limb previously, writing in the BMJ, leaders of NHS organisations in England have voiced grave warnings about how the build up of financial pressures is affecting the care of patients (Limb, 2013). Current updated NICE guidelines (CG156) recommend that women under 42 years with unexplained infertility should be offered three cycles of in vitro fertilisation funded by the NHS. Others state that all pregnant women should be able to choose an elective caesarean without obstetric or psychological indications.

The authors of this letter in the BMJ proposed that this,

“results in raised expectations that cannot be met and a flurry of referrals of disappointed women to the private sector.”

The authors specifically report that:

“Our anonymous telephone research involving all London maternity units two months ago showed that commissioners are unwilling to fund caesareans at maternal request. It also showed that women with previous caesareans are being pushed down the road of a trial of vaginal birth because of targets for reducing these operations. This causes great disappointment and anxiety for these women, who are often met with the clinician’s response “operations are more dangerous,”4 which is contrary to NICE guidance.

Furthermore, the postcode lottery for NHS funded in vitro fertilisation is well documented. We believe that these updated NICE guidelines will perpetuate the belief that these guidelines are only implementable for a

select educated few who can successfully argue their case with professionals. Others have called for legal clarity in this respect.”

The area of “judicial review” in civil litigation is the procedure by which the courts examine the decisions of public bodies to ensure that they act lawfully and fairly. On the application of a party with sufficient interest in the case, the court conducts a review of the process by which a public body has reached a decision to assess whether it was validly made. The court’s authority to do this derives from statute, but the principles of judicial review are based on case law which is continually evolving. Judicial review is very much a remedy of last resort. Although the number of judicial review claims has increased in recent years, it can be difficult to bring a successful claim and a court may refuse permission to bring a claim if an alternative remedy has not been exhausted. A claimant should therefore explore all possible alternatives before applying for judicial review.

Judicial review has a number of heads. For example, under the head of “legitimate expectation“, a public body may, by its own statements or conduct, be required to act in a certain way, where there is a legitimate expectation as to the way in which it will act. A legitimate expectation only arises in exceptional cases and there can be no expectation that the public body will act unfairly or beyond its power.

Judicial review, like arguably access to medicine, has been attacked by the current Government. The issue of infertility treatment illustrates, it can be argued, a national disgrace in poor access to both the medicine and the law. In an address to the CBI, David Cameron vowed to cut “time-wasting” caused by the “massive growth industry” in judicial reviews. He apparently wants fewer reviews, specifically for those challenging planning, and he wants to shorten the limitation period for bringing a review. This is all in aid of a new “growth cabinet” – cutting “red tape” and “bureaucratic rubbish” and “trying to speed decision making”.

Martha Gill writing in the New Statesman has argued that,

“At the moment, a judicial review is one of the only ways by which the courts can scrutinise the decisions of public bodies. Legal Aid is available for it – prisoners, for example, can bring judicial reviews against decisions of the parole board. So there are the cons – disempowering people who didn’t have much power in the first place, and increasing opportunities for public bodies to overstep the mark, unchallenged. What of the pros? Cameron argues that the judicial review industry is growing, holding up progress and costing money.”

Because of the “silo effect”, medics will have tended to notice on their watch a decline in universality and comprehensive nature of the NHS, with a focus on section 75 NHS regulations emphasising competitive tendering, but will be largely uncognisant of the battles the legal profession are facing of their own in the annihilation of high street legal aid services and cuts in judicial review. This letter in the BMJ from a leading Consultant’s firm at Guys’ and St.Thomas’ here in London demonstrates what a mess the confluence of these two policies, pretty horrific separately, can lead to.

References

Limb, M. (2013) Current financial pressures are worst ever, say NHS chiefs, BMJ, Jun 3, 346. f3616.

Mascharenas, M., Nash, Z., and Nathan, B. (2013) Letter: NICE promises on infertility and caesarean section are unmet, BMJ, Jun 18, 346.

Is socialism consistent with judicial review?

The simplest answer to, ‘Is socialism consistent with judicial review?’ might be ‘Yes absolutely – it’s a very useful way to hold authorities to account’.

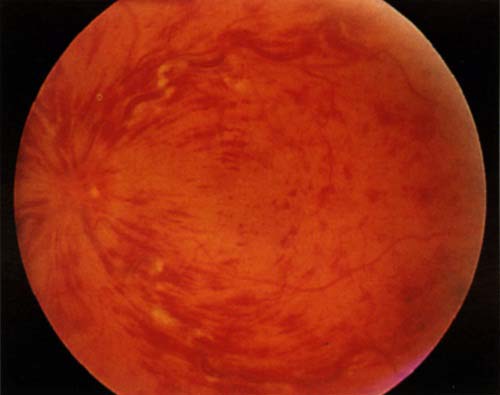

To my knowledge, “central retinal vein occlusion” is still a popular ‘spot diagnosis’ in the clinical examination for the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the UK.

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (“NICE”), as a public body with statutory powers from law, makes decisions about treatments in the NHS, and a number of its decisions have been subject to ‘judicial review’ in the past. Judicial review is a procedure in English law by which the courts in England and Wales can supervise the exercise of public power on the application of an individual. A person who feels that an exercise of such power by a government authority, such as a minister, the local council or a statutory tribunal, is unlawful, perhaps because it has violated his or her rights, may apply to the Administrative Court (a division of the High Court) for judicial review of the decision and have it set aside (quashed) and possibly obtain damages.

NICE concluded in July 2011 that dextramethasone-intravitreal implants implants, that are installed every six months and help prevent sight deterioration, and represented a cost-effective use of NHS resources. The macular is the central part of the retina responsible for colour vision and perception of fine detail. Macular oedema is where fluid collects in the retina at the macular area, which can lead to severe visual impairment. Straight lines may appear wavy, and one may have blurred central vision or sensitivity to light. However, according to a recent article in the Guardian newspaper, a survey of 125 hospital trusts in England with eye health services conducted by the Royal National Institute of Blind People in February found that of the trusts that responded, 45 were providing a full service and 37 were providing either a restricted service or no service. In his article, Sir Michael Rawlins in the Health Services Journal said he had advised the RNIB to make an application to the high court and seek a judicial review.

Socialism and judicial review, however, have not historically been natural ‘soulmates’. In EP Thompson’s “Whigs and Hunters” (1975), it is argued that judicial review (and ‘rule of law’) has been an useful way of exerting influence in capitalist ideologies, particular in the context of ‘abuse of power’. It can be argued that judicial review and ‘the rule of law’ go hand-in-hand in that the ‘rule of law’ fundamentally provides that nobody is above the law, and that the law is supreme. To that extent, everyone has an equal say, and judicial review can therefore represent the needs of underprivileged members of society. To that extent, it might be very reconcilable with socialism; sufferers of dementia might be considered some of the more disadvantaged members of society, and a decision to make cholinesterase inhibitors available for amelioration of cognitive symptoms might be a meritorious one in terms of fairness.

Many criticisms of judicial review have, interestingly, centred around the validity of the process. For example, it can be argued, reasonably effectively, that judges currently in England are not a representative stratum of the population. This is a general issue with the senior members of the legal profession, generally, and is essentially one to do with the politics of the judiciary, as discussed by JAG Griffith (1991). Judges in the High Court are not politically elected, and therefore there are qualms about them entering into questions of public policy; the counter-argument to that is that they are simply examining issues of procedural irregularity, fairness or legitimate expectation, amongst other grounds, of the wishes of parliament, defined originally by parliament. This contention has been most forceful when the politics have been seen as ideologically ‘strong’, such as under Margaret Thatcher. Judges have had a tendency to ignore the social values of society, and indeed many senior judges currently at the Bar in England and Wales emphasise that a robust advantage is conferred by judges not passing moralistic or other judgements based on social mores.

Perhaps the most compelling reason to reject judicial review, for socialists, is if judicial review is seen as a mechanism by capitalist societies to reject socialist values. In theory, any legal mechanism can only be interpreted by the political ideology which underlines it, at one end, but the judiciary and the legislature and executive are entirely separate in structure and function (it is argued, at the other end). However, a way to temper such criticism might be to argue that, even if socialism were not the prevailing ideology, socialism can exert a useful moralistic influence on decision-making which can make a real difference for a minority of patients in the NHS. Anyway, the validity of judicial review is a genuine problem legally, and, while I think instinctively it offers benefits to patients in a socialist NHS, its methodology should not escape from scrutiny altogether. As Prof Mauro Cappelletti indeed says, one page of practical tips is worth many books of abstract theory (or something like that!)