Home » Other (Page 2)

The Purple Angels’ Dementia Awareness Day, founded by Norman McNamara, on September 20th 2014!

I’m looking forward to the Purple Angels’ Dementia Awareness Day to be held on September 20th 2014.

This year’s chosen charity is “YoungDementia UK“, and here is the link to the “Just giving” page which has been set up.

Dementia is considered ‘young onset’ when it affects people under 65 years of age. It is also referred to as ‘early onset’ or ‘working age’ dementia.

However this is a somewhat arbitary age distinction which is becoming less relevant as increasingly services are realigned to focus on the person and the impact of the condition, not the age.

Dementia is a degeneration of the brain that causes a progressive decline in people’s ability to think, reason, communicate and remember.

Their personality, behaviour and mood can also be affected. Everyone’s experience of dementia is unique and the progression of the condition varies. Some symptoms are more likely to occur with certain types of dementia.

Dementias that affect younger people can be rare and difficult to recognise.

People can also be very reluctant to accept there is anything wrong when they are otherwise fit and well, and they may put off visiting their doctor.

They are of considerable interest to me, as my own Doctor of Philosophy was passed by the University of Cambridge in January 2001, on “Specific cognitive deficits in the frontal lobe dementias”.

Norman McNamara from Devon was diagnosed with dementia six years ago when he was just 50.

Although his father and grandmother had suffered from the condition, Mr McNamara did not expect it to be part of his future.

He said: It was never really in the back of my mind that I might get it.

“I think it came to a head when I set the kitchen on fire three times.”

After his diagnosis, McNamara, from Torquay, began blogging online about his experiences and during a phone call with a friend he had the idea of organising the first Dementia Awareness Day.

The event was marked all across the world for the first time on 17 September 2011.

Norman McNamara writes, regarding this year,

“We want this year to be the best ever, and you don’t have to wait until the 20th Sept 2014 to do some fundraising! It doesn’t matter if it’s today, tomorrow, the 20th Sept or even New Year’s Eve!’

“All that matters is that you hold a small event, be it a coffee morning, a football card, car boot, a bingo game, a concert or even a SKY DIVE!”

“It really doesn’t matter, just please be assured that every penny you raise and donate to this link will go straight to YoungDementia UK and be spent on those who need it most, those with Dementia!”

“So please, let me know what you are organising this year so we can advertise it, the more people know about it the more we will raise.”

Meet Norman and Terry: two people living with a dementia in different ways

“Dementia is not just about sitting in a bathroom all day, staring at the walls.”

So speaks Norman McNamara in his recent BBC Devon interview this week.

This may seem like a silly thing to say, but the perception of some of “people living with dementia” can be engulfed with huge assumptions and immense negativity.

The concept of ‘living well with dementia’ has therefore threatened some people’s framing of a person who happens to have one of the hundred or so diagnoses with dementia.

It’s possible memory might not be massively involved for someone who has been diagnosed with a dementia.

Or as “Dementia Friends” put it, “Dementia is not just about memory loss.”

Norman McNamara and Sir Terry Pratchett are people who are testament to this.

“If you made a mistake, would you laugh it off to yourself and say ‘Ha, ha, maybe it’s because I have dementia.””

If somebody else made a mistake, would you laugh at that person and say ‘Ha, ha, maybe it’s because you have dementia.” Definitely not.

There are about a hundred different underlying causes of dementia.

“Dementia” is as helpful a word as “cancer”, embracing a number of different conditions tending to affect different people of different ages, with some similarities in each condition which part of the brain tend to be affected.

These parts of the brain, tending to be affected, means it can be predicted what a person with a medical type of dementia might experience at some stage.

This can be helpful in that the emergence of such symptoms don’t come as much of a shock to the people living with them.

Elaine, his wife, noticed Norman was doing “weird and wonderful things”.

Norman says “my spatial awareness was awful”, and “I was stumbling and falling”.

Norman, furthermore, was putting “red hot tea in the fridge”, and “shower gel, instead of toothpaste, in [my] mouth”.

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a type of dementia that shares symptoms with both Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. It may account for around 10 per cent of all cases of dementia. It is not a rare condition.

It is thought to affect an estimated 1.3 million individuals and their families in the United States.

Problems in recognising 3-D objects, “agnosia”, can happen.

Lewy bodies, named after the doctor who first identified them, are tiny deposits of protein in nerve cells.

See for example this report in this literature.

“Night terrors” have long been recognised in diffuse lewy Body disease.

“The hallucinations are terrific”

The core features tend to be fluctuating levels of ability to think successfully, with pronounced variations in attention and alertness and recurrent complex visual hallucinations, typically well formed and detailed.

See for example this account.

For Norman, it was ‘prevalent in his family’.

Other than age, there are few risk factors (medical, lifestyle or environmental) which are known to increase a person’s chances of developing DLB.

Most people who develop DLB have no clear family history of the disease. A few families do seem to have genetic mutations which are linked to inherited Lewy body disease, but these mutations are very rare.

The patterns of blood flow can help to confirm an underlying diagnosis (see this helpful review).

Also, in this particular ‘type of dementia’, it can be helpful for medical physicians to avoid certain medications (which people with this condition can do very badly with). So therefore while personhood is important here an understanding of medicine is also helpful in avoiding doing harm to a person living with dementia.

However, Norman has been tirelessly campaigning: he, for example, describes how hundreds of businesses in the Torbay-area of Devon have signed up for ‘dementia awareness.”

And, as Norman says, “When you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met one person with dementia.”

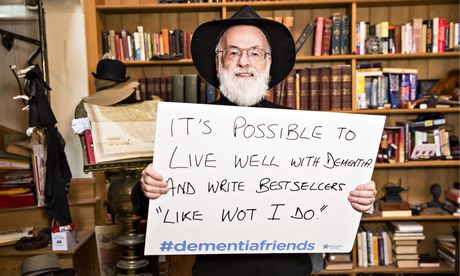

Sir Terry Pratchett is another person living with dementia.

Sir Terry Pratchett described on Tuesday 13th May 2014 the following phenomenon bhe had noticed:

“That nagging voice in their head willing them to understand the difference between a 5p piece and £1 and yet their brain refusing to help them. Or they might lose patience with friends or family, struggling to follow conversations.”

“Astereognosis” is a feature of ‘posterior cortical atrophy’ (“PCA”).

A good review on the condition of PCA is here.

Sir Terry Pratchett has written a personal reflection on society’s response to dementia and his own experience of Alzheimer’s to launch a new blog for Alzheimer’s Research UK: http://www.dementiablog.org

Sir Terry became a patron of Alzheimer’s Research UK in 2008, shortly after announcing his diagnosis with posterior cortical atrophy, a rare variant of Alzheimer’s disease affecting vision.

He went on to make a personal donation of $1 million to the charity, and has subsequently campaigned for greater research funding, including delivering a major petition to No.10 and countless media appearances.

In his inaugural post for the blog, Sir Terry Pratchett writes: “There isn’t one kind of dementia. There aren’t a dozen kinds. There are hundreds of thousands. Each person who lives with one of these diseases will be affected in uniquely destructive ways. I, for one, am the only person suffering from Terry Pratchett’s posterior cortical atrophy which, for some unknown reason, still leaves me able to write – with the help of my computer and friend – bestselling novels.”

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) refers to gradual and progressive degeneration of the outer layer of the brain (the cortex) in the part of the brain located in the back of the head (posterior).

The symptoms of PCA can vary from one person to the next and can change as the condition progresses. The most common symptoms are consistent with damage to the posterior cortex of the brain, an area responsible for processing visual information.

Consistent with this neurological damage are slowly developing difficulties with visual tasks such as reading a line of text, judging distances, and distinguishing between moving objects and stationary objects.

Other issues might be an inability to perceive more than one object at a time, disorientation, and difficulty maneuvering, identifying, and using tools or common objects.

Some persons experience difficulty performing mathematical calculations or spelling, and many people with PCA experience anxiety, possibly because they know something is wrong. In the early stages of PCA, most people do not have markedly reduced memory, but memory can be affected in later stages.

Astereognosis (or tactile agnosia if only one hand is affected) is the inability to identify an object by active touch of the hands without other sensory input.

An individual with astereognosis is unable to identify objects by handling them, despite intact sensation. With the absence of vision (i.e. eyes closed), an individual with astereognosis is unable to identify what is placed in their hand. As opposed to agnosia, when the object is observed visually, one should be able to successfully identify the object.

Living well with dementia means different things to different people.

Pratchett further writes:

“For me, living with posterior cortical atrophy began when I noticed the precision of my touch-typing getting progressively worse and my spelling starting to slip. For an author, what could be worse? And so I sought help, and will always be the loud and proud type to speak my mind and admit I’m having trouble. But there are many people with dementia too worried about failing with simple tasks in public to even step out of the house. I believe this is because simple displays of kindness often elude the best of us in these manic modern days of ours.”

As we better understand what dementia is, our response as a society can be more sophisticated. I’ve found one of the most potent factors for encouraging stigma and discrimination is in fact total ignorance.

Both Norman and Terry demonstrate wonderfully: it’s not what a person cannot do, it’s what they CAN DO, that counts.

This is ‘degree level’ “Dementia Friends” stuff, but I hope you found it interesting.

“The Alzheimer’s Show” tomorrow and Saturday: my competition

I’m going to the Alzheimer’s Show tomorrow and on Saturday (Friday 15th May and Saturday 16th May 2014) in London Olympia. I am looking forward to seeing and chatting with many of my friends there.

I quite like the approach of the show as it is accessible to people with dementia as well as people who help to support people living with dementia.

The show’s official flier can be downloaded off their official website.

There’ll be over exhibitors including care at home, care homes, living aids, funding, legal advice, respite care, complementary therapies, training, telecare, assistive technology, charity, research, education, finance and entertainment.

You’ll get a chance to be a “Dementia Friend“.

I have written about the five key messages of “Dementia Friends”, as my PhD was successfully awarded in the cognitive neuropsychology of dementia at the University of Cambridge.

My slot – “Meet the author”

I’m thrilled to be doing a half an hour slot called ‘Meet the author': details here.

My book is called “Living well with dementia”. It also happens to be the name of the current five-year English dementia policy, about to be renewed.

(@mrdarrengormley and I)

I was especially honoured to receive this book review from the prestigious ‘Nursing Times‘.

I feel very strongly that living well with dementia must be a critical plank in the renewed English dementia policy, whichever party/parties come to power on May 8th 2015.

As I explained in my short article in the “ETHOS” journal, living well with dementia is perfectly understandable in the context of integrated care or whole person care.

There’s no doubt that values-based commissioning, promoting wellbeing in dementia, should be a core feature of English health policy in the near future. I discuss one application here in the Health Services Journal recently.

My competition

To be eligible you will need to be at the Alzheimer’s Show on one of the two days to pick up your prize.

Required:

Simply respond to the following –

You must tweet this by the day on which you intend to be at the Alzheimer’s Show.

If no two people are the same, how can we build ‘dementia friendly communities’?

Even identical twins act differently.

This is because they are shaped by the environment in unique ways, even if they have exactly genetic sequence as the blueprint which designed them.

It therefore cannot be any surprise that no two individuals in society are in the same, as you can easily witness with the range of opinions on your timeline on Twitter.

A person with a dementia might be very different to another person with a dementia.

There are a hundred different causes of dementia, tending to affect people in different age groups in distinct ways at different rates? Let’s pick one type of dementia, the most common cause, Alzheimer’s disease.

A 83 year-old with Alzheimer’s disease might have a number of different problems, for example memory – or even with problems in planning, aspects of language, or behaviour.

And of course it’s pretty likely that 83 year-old might be living with another different condition too, such as heart disease.

Your perception of that 83 year-old might vary from your next-door neighbour, according to, perhaps, your own personal experiences of dementia, good, bad or neither.

So, in raising awareness over the uniqueness of individuals through “Dementia Friends” or “Dementia Champions”, there’s an inherent contradiction.

How do we build ‘dementia friendly communities’, given one’s desire to embrace diversity?

I have for some time explained elsewhere why I think the term is a misnomer. I don’t see the point of “asthma friendly communities” or “chronic demyelinating polyneuropathy communities”, worthy though they are.

I think when you pick off any of the ‘protected characteristics’ in the Equality Act, such as ‘disability’, ‘sexual orientation’ or ‘age’, you have to be careful about not inadvertently homogenising groups of people, worthy though the cause of ensuring that they do not suffer any unfair detriment is.

It could be that people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, due to how the condition tends to affect the brain, could have particularly problems with spatial memory or navigation. Therefore, it would be desirable perhaps to have places with clear landmarks such that such individuals can navigate themselves around.

But take this situation to an extreme. Would society feel comfortable with people with dementia having their own cafés?

The story of Rosa Parks is well known.

After working all day, Parks boarded the Cleveland Avenue bus around 6 p.m., Thursday, December 1, 1955, in downtown Montgomery. She paid her fare and sat in an empty seat in the first row of back seats reserved for blacks in the “coloured” section.

The bus driver moved the “coloured” section sign behind Parks and demanded that four black people give up their seats in the middle section so that the white passengers could sit.

Rosa did not move.

A legitimate learning objective of ‘dementia awareness’ sessions is to think about what a person with dementia might or might not be able to do.

But if we then meet this learning objective, that people with dementia are all unique, we should steer away from stereotypes that people with dementia act ‘a certain way’.

This, I personally believe, is a big failing of this ‘dementia friendly communities awareness video’.

How Can We Include People With Dementia in Our Community? from NEIL Programme on Vimeo.

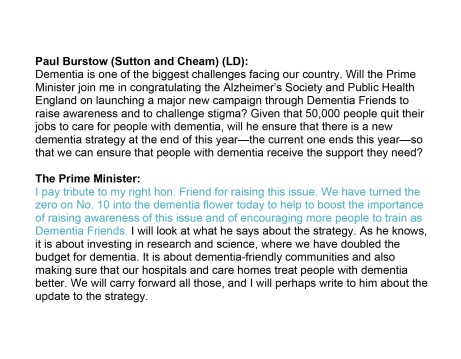

2 Qns in #pmqs on dementia, but 2 As on ‘Dementia Friends’ not living well with dementia

Dementia was mentioned twice today in Prime Minister’s Questions.

There was a ‘big announcement’ today from the Alzheimer’s Society which could have been used to convey the meaning of how people living with dementia could be encouraged to live well in productive lives.

As part of this publicity, Terry Pratchett was pictured holding up a placade saying, “It’s possible to live well with dementia and write bestsellers “like what I do””.

An Independent article carries the main thrust of this message:

“Up to £1.6 billion a year is lost to English business every year, as employees take time off or leave work altogether to provide at-home care for elderly relatives, according to the report, compiled by the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR).”

“On top of those that stop working, another 66,000 are making adjustments to their work arrangements, such as committing to fewer hours or working from home.”

Paul Burstow MP brought up the first question specifically around this initiative.

Here is the Question/Answer exchange as described in Hansard:

The answer fails spectacularly to address the issue of living well with dementia, but is a brilliant marketing shill for ‘Dementia Friends’.

There’s no attempt to include any other charity working in dementia.

It doesn’t mention the C word either – Carers.

And then it was left up to Hazel Blears MP to provide another question on dementia.

This time it’s a bit different.

There’s no answer on how zero hours contracts cannot specifically in the care system promote living well for either carers (including unpaid careworkers) or persons with dementia.

But it’s exactly the same otherwise.

A brilliant marketing shill for Dementia Friends, and no mention of any other charity working on dementia.

Quite incredibly here, Cameron produces an answer on ‘caring’ in dementia without mentioning carers or careworkers.

With Ed Miliband, Ed Miliband and David Cameron all wearing their ‘Dementia Friends’ badges, is it any wonder you never hear about Dementia UK’s Admiral Nurses any more?

There is undoubtedly a rôle for all players in a plural vibrant community, but this should never have been allowed to become an ‘either’/’or’ situation.

Really proud of my friends living well with dementia at #ADI2014 Puerto Rico

29th International Conference of Alzheimer’s Disease International

Dementia: Working Together for a Global Solution

1-4 May 2014, San Juan, Puerto Rico

ADI and Asociacion de Alzheimer y Desordenes Relacionados de Puerto Rico invite representatives from around the world, from medical professionals and researchers to people with dementia and carers, all with a common interest in dementia.

The conference programme – details given on this website – has streams including research, advocacy and care.

I am particularly proud of my close friend, Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer).

Kate is in a volunteer advocacy position, also working as a consumer on the National Advisory Consumers Committee, and the Consumer’s Dementia Research Network.

She contributes so much value to the people who are lucky to know her.

Kate lives in Adelaide, Australia. She loves cats like me. She has a formidable interest and experience in many things such as academia, media, clinical quality, and cuisine. She happens to live with first-hand experience of living with a dementia, and is a sheer joy to learn off.

Dementia Alliance International is a non-profit group of people with dementia from the USA, Canada, Australia and other countries that seek to represent, support, and educate others living with the disease, and an organization that will provide a unified voice of strength, advocacy and support in the fight for individual autonomy and improved quality of life.

Their membership is open to anyone with any type of dementia. Click here to inquire about membership.

PHOTOS ALL BY KATE SWAFFER APART FROM THE ONES WITH KATE IN THEM

Kate sporting a very important message for those of us who are passionate about a person-centred approach promoting living well with dementia.

This philosophy does not give undue priority to a medical model which pushes drugs which currently have very modest effects, or certain vested interests.

Living well with dementia in the English jurisdiction is a policy plank I’ve extensively reviewed for the English jurisdiction here.

A wonderful picture of Kate and Gill (@WhoseShoes). I am very proud of them having made this global journey to Puerto Rico.

My three abstracts to be submitted for @AlzheimerEurope this year: 2 ‘people’ and 1 ‘policy’

I’ve decided to apply to go to the Alzheimer’s Europe conference this year.

It is being held in my birth place, Glasgow.

Details are here.

I follow @AlzheimerEurope

and they follow me.

Here are my three topics.

Policy (Socio-economic cost of dementia and financing of care): Would knowing your genetic risk for dementia change the way you behave with the NHS?

People (Perception and identity): An analysis of 75 English language web articles on the G8 dementia summit

People (Perception and identity): Who were the biggest winners and losers of the G8 dementia summit? My survey of 96 persons in the UK without dementia.

A person newly diagnosed with dementia has a question for primary care, and primary care should know the answer

Picture this.

It’s a busy GP morning surgery in London.

A patient in his 50s, newly diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, a condition which causes a progressive decline in structure and function of the brain, has a simple question off his GP.

“Now that I know that I have Alzheimer’s disease, how best can I look after my condition?”

A change in emphasis of the NHS towards proactive care is now long overdue.

At this point, the patient, in a busy office job in Clapham, has some worsening problems with his short term memory, but has no other outward features of his disease.

His social interactions are otherwise normal.

A GP thus far might have been tempted to reach for her prescription pad.

A small slug of donepezil – to be prescribed by someone – after all might produce some benefit in memory and attention in the short term, but the GP warns her patient that the drug will not ultimately slow down progression consistent with NICE guidelines.

It’s clear to me that primary care must have a decent answer to this common question.

Living well is a philosophy of life. It is not achieved through the magic bullet of a pill.

This means that that the GP’s patient, while the dementia may not have advanced much in the years to come, can know what adaptations or assistive technologies might be available.

A GP will have to be confident in her knowledge of the dementias. This is an operational issue for NHS England to sort out.

He might become aware of how his own house can best be designed. Disorientation, due to problems in spatial memory and/or attention, can be a prominent feature of early Alzheimer’s disease. So there are positive things a person with dementia might be able to do, say regarding signage, in his own home.

This might be further reflected in the environment of any hospital setting which the patient may later encounter.

Training for the current GP is likely to differ somewhat from the training of the GP in future.

I think the compulsory stints in hospital will have to go to make way for training that reflects a GP being able to identify the needs of the person newly diagnosed with dementia in the community.

People will need to receive a more holistic level of support, with all their physical, mental and social needs taken into account, rather than being treated separately for each condition.

Therefore the patient becomes a person – not a collection of medical problem lists to be treated with different drugs.

Instead of people being pushed from pillar to post within the system, repeating information and investigations countless times, services will need to be much better organised around the beliefs, concerns, expectations or needs of the person.

There are operational ways of doing this. A great way to do this would be to appoint a named professional to coordinate their care and same day telephone consultations if needed. Political parties may differ on how they might deliver this, but the idea – and it is a very powerful one – is substantially the same.

One can easily appreciate that people want to set goals for their care and to be supported to understand the care proposed for them.

But think about that GP’s patient newly diagnosed with dementia.

It turns out he wants to focus on keeping well and maintaining his own particular independence and dignity.

He wants to stay close to his families and friends.

He wants to play an active part in his community.

Even if a person is diagnosed with exactly the same condition or disability as someone else, what that means for those two people can be very different.

Once you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve done exactly that: you happen to have met one person with dementia.

Care and support plans should truly reflect the full range of individuals’ needs and goals, bringing together the knowledge and expertise of both the professional and the person. It’s going to be, further, important to be aware of those individuals’ relationships with the rest of the community and society. People are always stronger together.

And technology should’t be necessarily feared.

Hopefully a future NHS which is comprehensive, universal and free at the point of need will be able to cope, especially as technology gets more sophisticated, and cheaper.

Improvements in information and technology could support people to take control their own care, providing people with easier access to their own medical information, online booking of appointments and ordering repeat prescriptions.

That GP could herself be supported to enable this, working with other services including district nurses and other community nurses.

And note that this person with dementia is not particularly old.

The ability of the GP to be able to answer that question on how best her patient can lead his life cannot be a reflection of the so-called ‘burden’ of older people on society.

Times are definitely changing.

Primary care is undergoing a silent transformation allowing people to live well with dementia.

And note one thing.

I never told you once which party the patient voted for, and who is currently in Government at the time of this scenario.

Bring it on, I say.

Compassion like smiles can’t be faked

One management ethos is ‘make up an arbitrary targets, and follow them at a molecular level’.

Targets are intrinsically rewarding for managers who want to be seen to be doing something.

A million dementia friends doesn’t necessarily mean an improved understanding of dementia.

There’s no point denying compassion, meticulously cultivated in medicine, nursing and social care training, is pivotal.

It is also crucially important in basic humanity, whether you believe in society or not.

@Ermintrude2 @MrDarrenGormley @legalaware @jmcefalas @kykaree You’re right. Genuine Compassion is beautiful but I now flinch when I hear it.

— Alison Cameron (@allyc375) April 21, 2014

Compassion and leadership are areas of motherhood and apple pie.

Can see them in their office “but what fool would ever argue against compassion?” @allyc375 @legalaware @jmcefalas @Ermintrude2 @kykaree

— Darren Gormley (@MrDarrenGormley) April 21, 2014

But the idea of ‘compassion on demand’ has put shivers up people.

@MrDarrenGormley @legalaware @jmcefalas @Ermintrude2 @kykaree Lovely as it is REAL not churned out on demand in a circle in a training room.

— Alison Cameron (@allyc375) April 21, 2014

All political parties have been especially bad at this approach to the caring professions, some more than others perhaps.

Liberalising the market has seen its own unintended consequences.

What is clear is that regulation is needed to safeguard vulnerable individuals.

Take for example what has happened in the National Health Service.

There is no doubt that some targets are useful – e.g. cancer waiting times – but some targets appear to have been there for the benefit of the managers, local and national politics, rather than quality of health care.

It might be true that many people are simply not as happy as they should be.

A study reported in the Daily Mail, from some time ago, throws some light on this, using the uSwitch.com European Quality of Life Index. Britain is the worst place in Europe to live despite offering the biggest salaries, a study revealed today. Researchers weighed up official data for ten European countries, including France, Spain, Germany, Italy, Sweden and Poland. High incomes in the UK are cancelled out by long working hours, poor annual leave, rising food and fuel bills and a lack of sunshine.

Take, for example, “the simple smile”.

A smile is a facial expression formed by flexing the muscles near both ends of the mouth.

Among humans, it is customarily an expression denoting pleasure, happiness, or amusement, but can also be an involuntary expression of anxiety, in which case it is known as a grimace.

Cross-cultural studies have shown that smiling is a means of communicating emotions throughout the world, but there are large difference between different cultures.

Although many different types of smiles have been identified and studied, researchers have devoted particular attention to an anatomical distinction first recognised by French neurologist Guillaume Duchenne. While conducting research on the physiology of facial expressions in the mid-nineteenth century, Duchenne identified two distinct types of smiles.

A Duchenne smile involves contraction of both the zygomatic major muscle (which raises the corners of the mouth) and the orbicularis oculi muscle (which raises the cheeks and forms crow’s feet around the eyes).

A non-Duchenne smile involves only the zygomatic major muscle.

Many researchers believe that Duchenne smiles indicate genuine spontaneous emotions since most people cannot voluntarily contract the outer portion of the orbicularis oculi muscle.

So, in the same way you can’t physiologically fake a smile, you can’t fake happiness.

You can’t as such ‘fake targets’ but you can certainly game them.

It might not be obvious to people from non-clinical backgrounds that an understaffed health service will find it tough to deliver care to their standards.

Whether clinical regulators care in reality about an under-resourced NHS truly functions is up to them.

How they deal with whistleblowers speaking out safely about the NHS is up to them.

We do know that NHS managers like ‘shiny products’.

But what is clear is that selling compassion is therefore as unconvincing as faking a smile.

Like Matisse’s artwork, living well with dementia is a triumph of hope over pessimism

You can feel it from start to finish.

Matisse is innovation all over.

It’s about experimenting.

It’s about not being frightened of failure.

It’s about not worrying what people think of you.

It’s about cracking a few eggs to make an omelette.

It was a delight to go to London SE1 “Tate Modern” to see “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs” this afternoon.

A dementia expert is reputed today as saying that Alzheimer’s disease impacts ‘not only color, awareness and your ability to process [things] but also your field of vision.’

‘By then your brain says “I can’t deal with this data coming from two eyes” and it says “I’ll just pay attention to one.”

‘You lose all depth of perception, you’re not able to figure out [if things are] three-dimensional or two-dimensional.’

And indeed it’s scary stuff.

I am unable to bring you the image as it would be a breach of copyright.

I object very strongly to these scare tactics.

But they’re utterly in keeping with the “timebomb” school of reporting of dementia.

The facts are as follow.

Vision is not affected in early Alzheimer’s disease as the part of the brain which is typically affected are the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, a part of the brain near the ear.

The visual areas are somewhere completely different.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia worldwide, though there are about 100 different types of dementia.

There might be a case for saying vision is affected in some other types of dementia, for example visual hallucinations in diffuse lewy body disease or in 3D visual perception as in posterior cortical atrophy.

But this is completely different.

The advertising campaign is in fact disgusting, but entirely in keeping with how corporate-behaving charities can resort to shock-doctrine type tactics.

In contrast, Matisse is a triumph of hope over pessimism.

It’s brilliant that, while Matisse’s own movement was severely limited, in “The Acrobats” he was able to depict bodies in extremes of motion.

The assistants would clamber around the giant pictures with pin cushions and hammers, realising Matisse’s vision.

The colour was sensational, at a time when this was not the “done thing” in art at the time.

In fact, Matisse epitomises everything which the doom-mongers, sometimes ably assisted by some dementia charities and the media, portray dementia to be.

Living well with dementia for me is about the assets-based approach.

It’s about celebrating what people can do as individuals, rather than what they can’t do.

It’s not about propelling our fellow citizens into an early grave.

I know which world I prefer to inhabit.