Home » Other (Page 3)

The legacy of “One hundred years of solitude”: a truly innovative exploration of a type of dementia

Nobel prize-winning Colombian author Gabriel Garcia Marquez has died in Mexico aged 87.

Garcia Marquez was considered one of the greatest Spanish-language authors, best known for his masterpiece of magical realism, “One Hundred Years of Solitude”.

The 1967 novel sold more than 30 million copies and he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982.

And yet many don’t appreciate the relevance of this work to dementia.

In his renowned novel, García Márquez depicts the plight of Macondo, a town struck by the dreaded insomnia plague. The most devastating symptom of the plague is not the impossibility of sleep, but rather the loss of ‘the name and notion of things’.

The description in One Hundred Years of Solitude is very similar to that of the cognitive difficulties experienced by patients with semantic dementia (SD).

In an effort to combat this insidious loss of knowledge, the protagonist, José Arcadio Buendía, ‘marked everything with its name: table, chair, clock, door, wall, bed, pan’. ‘Studying the infinite possibilities of a loss of memory, he realized that the day might come when things would be recognized by their inscriptions but that no one would remember their use’.

Semantic dementia, a clinical syndrome characterized by a progressive breakdown of conceptual knowledge (semantic memory) in the context of relatively preserved day-to-day (episodic) memory.

Remarkably, García Márquez created a striking literary depiction of collective semantic dementia before the syndrome was recognized in neurology.

Garcia Marquez had been ill and had made few public appearances recently.

He achieved fame for pioneering magical realism, a unique blending of the marvellous and the mundane in a way that made the extraordinary seem routine.

With his books, he brought Latin America’s charm and teaming contradictions to life in the minds of millions of people.

Muere Gabriel García Márquez. Mercedes y sus hijos, Rodrigo y Gonzalo, me autorizan dar la información. Que tristeza tan profunda…

— Fernanda Familiar (@qtf) April 17, 2014

Although frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia are associated with different overall patterns of brain atrophy, regions of gray matter tissue loss in the orbital frontal, insular, and anterior cingulate regions are present in both groups.

The clinical syndrome now widely referred to as semantic dementia was fi rst described at the beginning of the 20th century by Arnold Pick, a remarkable neuropsychiatrist, neuropathologist, and linguist working in Prague, and by several other early behavioural neurologists.

Oddly enough, given the striking nature of the syndrome, this early work was followed by a long period of neglect; but about three-quarters of a century later, two initially separate streams of investigation converged to reawaken interest.

In 1975, Elizabeth Warrington, now Professor Emeritus at Queen Square and lifelong doyenne of neuropsychology working with other greats such as Prof Ros Mccarthy, described three patients with a combination of visual associative agnosia, anomia, and disrupted comprehension of word meaning.

Shortly before this report, Tulving had proposed a distinction between episodic (facts) and semantic (concepts) a memory, with the former referring to personally experienced memories specifi c to time and place, and the latter to culturally shared knowledge of word and object meaning.

Drawing on this distinction, Warrington concluded that her three patients had a selective loss of semantic memory rather than several separate cognitive deficits.

Dementia is a condition causing a steady decline in functions of the brain, accompanied by changes which can either be seen on a microscopic or macroscopic level, due to some underlying process.

The most common type of dementia worldwide is Alzheimer’s disease, typified in its early stages by a decline in short term learning and memory.

Here are Dr Peter Gordon, Kate Swaffer and Norman McNamara talking about my book.

For more information about my book, please refer to this page.

Did the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge park a ‘National Care Service’ for good?

I’m still unclear where and when the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge came about.

The lack of a clear audit trail for the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge

I know that it was launched in March 2012.

“Dementia” is not mentioned in the Conservative Party Manifesto for the general election of 2010. It is however mentioned in the Coalition Agreement, with broadly the same wording as the Liberal Democrat manifesto 2010, but that still doesn’t explain how this became the “Prime Minister’s Challenge”.

In summary, the one line in the Coalition Agreement is drafted as follows:

“We will prioritise dementia research within the health research and development budget”

But still no specific mention of that “Challenge”.

The distortion effect of the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge

The Dementia Challenge prioritises the Alzheimer’s Society, and it is clear that other charities, such as Dementia UK (which is experiencing threats of its own to its superb ‘Admiral nurses’ scheme) trying to plough on regardless.

Indeed, many supported the fundraising for Dementia UK only this morning in the London Marathon too.

There is no official cross-party consensus on the “Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge”, though individual Labour MPs support the activities of “Dementia Friends”.

The market dominance of the Alzheimer’s Society for ‘Dementia Friends’ compared to other charities does not seem to have been arrived at particularly democratically either. There is no conceivable reason why other big players, such as “Dementia UK” or the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, were excluded from this friendship initiative.

Ironically, Japan upon which befriending is modelled is not ashamed of its care service.

It is palpably unacceptable if people are ‘more aware of dementia’ without a concominant investment in specialist memory clinics, or care and support services.

Genuine concerns from stakeholders involved with dementia care

It is clear amongst my followers on Twitter that the nature of this “Challenge” is causing considerable unease.

Agreed “@Ermintrude2: @Cleverestcookie @legalaware exactly. it isn’t dementia thats the challenge. It’s the health and social care system.”

— Liz Wilson (@aphidcatcher) April 13, 2014

Concidentally I was reminded of this this morning:

« Be wary of the man who urges an action in which he himself incurs no risk. » Seneca http://t.co/0PgxlIVbrF — Philosophers quotes (@philo_quotes) April 13, 2014

But there are now some very serious questions about this policy, particularly from the ‘zero sum gain’ effect it has had knock-on in other areas of dementia policy.

@Bexmoxon @Cleverestcookie @Ermintrude2 @legalaware people living dementia, their carers, practitioners etc views taken piecemeal as per

— Mark Barlow (@mark_b33) April 13, 2014

@Ermintrude2 @legalaware @mark_b33 IME they often don’t talk to the right people. Not the people with current links to actually what’s doing — Cathy Cooke (@Cleverestcookie) April 13, 2014

When @Ermintrude2 looked into this at the time, the response was a bit confused.

@mark_b33 @legalaware I think they are looking at the wrong problems. I was told by a DH official that agenda set by talking to..

— Ermintrude (@Ermintrude2) April 13, 2014

@mark_b33 @legalaware “the great and the good” (her words). That is EXACTLY the challenge that needs tackling. Govt talking to same people. — Ermintrude (@Ermintrude2) April 13, 2014

And indeed Ermintrude has penned some thoughts at the time on this high impact blog.

What has happened to social care in the name of ‘improvement’, I agree, is very alarming.

@legalaware The Dementia Challenge – smoke and mirrors. Nice platform for government to make people think they are doing stuff..

— Ermintrude (@Ermintrude2) April 13, 2014

@legalaware seeing how utterly offensive it is for govt to make these ‘improvement’ statements or pretend they care when they are.. — Ermintrude (@Ermintrude2) April 13, 2014

But we do know full-well about the ‘democratic deficit’.

False pledges and threats, and unfulfilled promises

The general public were unaware that a 493 Act of parliament called the ‘Health and Social Care Act’ would be sprung on them, with a £3 bn top-down reorganisation.

But this was Lansley’s “emergency conference” on Labour’s “secret death tax” in February 2010.

A number of views were expressed at the time, including the need for better care from the Alzheimer’s Society at the time under a different CEO.

The full thrust of ‘Dementia Friends’ is a total change of mood music from February 2010’s concerns of the Alzheimer’s Society reported here:

“Care and treatment for sufferers of dementia should be at the heart of the general election campaign, the Alzheimer’s Society charity has said.”

Where has the Society been in campaigning on swingeing cuts in social care?

Also, in February 2010, Gordon Brown’s speech at the King’s Fund was reported, where Brown made a significant pledge.

“Mr Brown also announced that the government’s planned reforms to community and primary care health services also included a commitment to provide dedicated “one-to-one”nursing for all cancer patients in their own homes, over the next five years.”

We do know that the NHS has been persevering with this programme with ‘efficiency savings’.

In October 2012, it was reported that nearly £3bn was indeed returned to the Treasury, and it is unclear how, if it at all, it was returned to front line care.

So it’s possible that Brown’s plan, the subject of a hate campaign at the time from the Tory press, might have worked in fact.

Dilnot

In 2010 Andrew Dilnot had been tasked by the then government to propose a solution to the crisis in social care.

The response was from February 2013, after the top-down reorganisation.

“Mr Dilnot suggested a cap on how much anyone would be required to pay for their care costs over the course of a lifetime, suggesting a ceiling of between £25,000 and £50,000 (in 2010/11 prices). Beyond this point, the state would take on responsibility for the majority of the bill.

The Government today announced that from 2017 it intends to establish a cap of £75,000 in 2017 prices which, according to Mr Dilnot’s calculations, equates to approximately £61,000 in the 2010/11 prices (the basis of his report). If we’re to make a claim about the extent to which the Government has ‘watered down’ Mr Dilnot’s proposal, it’s crucial that we account for this inflationary effect.”

Resurrection of the ‘National Care Service’ by Andy Burnham MP yesterday, Shadow Secretary of State for Health

This issue may have to be revisited at some stage. Andy Burnham MP yesterday in the Bermondsey Village Hall, without much press present, mooted the idea of how a social care service could be established on the founding principles of the NHS, and would be a significant departure from the piecemeal 15-minute slot carers.

Burnham stated that care provided by inexperienced staff on zero-hour contracts was a problem.

An experienced member of the audience highlighted the phenomenal work done by unpaid family caregivers particularly for dementia.

The topic of a compulsory state insurance is interesting.

In his classic article, Kenneth Arrow (1963) argues that, where markets fail, other institutions may arise to mitigate the resulting problems: ‘the failure of the market to insure against uncertainties has created many social institutions in which the usual assumptions of the market are to some extent contradicted’ (p. 967).

Rationale for this method of funding

A great advantage of ‘social insurance’ is, because membership is generally compulsory, it is possible (though not essential) to break the link between premium and individual risk.

There might be other important aspects. For example, both employers and employees pay contributions. Also, there might be Government support for those who are unable to pay goes through the insurance fund.

The philosopher John Rawls (1972) argues that in a just society the rules are made by people who do not know where they will end up in that society, that is, behind what he called the “Veil of Ignorance”.

Insurance can be interpreted as an example of solidarity behind the Veil of Ignorance: a person who joins a risk pool does not know in advance whether or not he will suffer a loss and hence have to make a claim. Insurance thus has moral appeal.

Ultimately there is a problem as to what type of care might be covered.

Does the policy cover only residential care, or also domiciliary care; is a person entitled to residential care on the basis of general infirmity or only if he or she has clearly-defined, specific ailments?

In the Dilnot recommendations, the cap on care payments did not include the “hotel costs” that a care home will charge. In other words, people in residential care will still need to pay (at the Dilnot report’s estimate) between £7,000 and £10,000 per year to fund their accommodation and living expenses.

Furthermore, how will the answers to these questions change with advances over the years with changes in the actual prevalence of dementia, or in the implementation of ever increasingly sophisticated medical technology?

It has been proposed (Lloyd 2008) that long-term care could be financed via social insurance, with the premium paid as a lump sum either at age 65 or out of a person’s estate. The idea behind this proposal is twofol.

Firstly, as a person gets older, the range of uncertainty about the probability of needing long-term care becomes smaller.

Secondly, if a person can buy insurance for a single premium payable out of his or her estate, the cost of long-term care does not impinge on his or her living standard during working life or in retirement, but can frequently be taken from housing wealth.

Development of social health insurance systems have normally been in response to concerns that inadequate resources were mobilised to support access to health services.

The continuing swingeing cuts in social care

And these cuts have continued: this report is from March 12 2014,

“An analysis by Mind found that the number of adults with mental health needs who received social care support has fallen by at least 30,000 since 2005, a drop of 21%. Cuts to local authority social care budgets – the majority of which have hit since 2009 – have left a funding shortfall for care of up to £260 million, the charity said.”

Since there is no simple answer to the question of how much is the appropriate level of support, the issue of adequacy is best thought of as being a level that is considered appropriate in the country given its total resources, preferences and other development priorities.

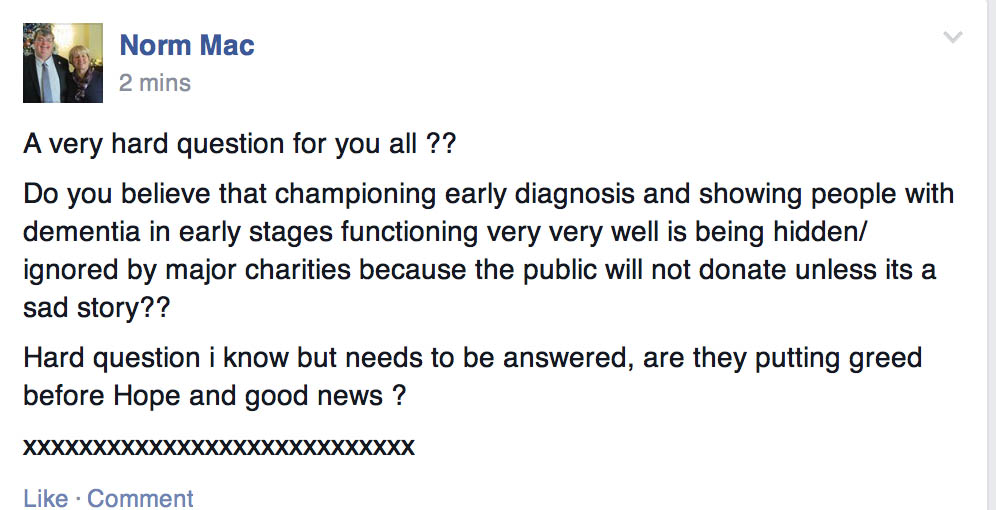

And where are people from charities campaigning on this issue?

This issue of course was not considered at all in the G8 Dementia Summit, which focused on more monies for personalised medicine, genetic and molecular biology research, in response to concerns from an “ailing industry”.

Conclusion

I am actually truly disgusted at this unholy mess.

References

Arrow, Kenneth F. (1963), ‘Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care’, American Economic Review, 53: 941–73; repr. in Cooper and Culyer (1973: 13–48), Diamond and Rothschild (1978: 348–75), and Barr (2001b: Vol. I, 275-307).

Lloyd, James (2008), Funding Long-term Care – The Building Blocks of Reform, London: