Home » Health and Social Care Act 2012 (Page 2)

The “Tony Blair dictum” (revisited)

Labour themselves perhaps wished to “open up” the NHS to more private sector involvement, even if they did not “introduce” the private market approach to the NHS: it is felt by many that was successfully achieved in the 1980s under the previous Thatcher administration. More recently, the details of “independent sector treatment centres”, and criticisms about their relative inefficiency, introduced under the previous Labour administration are well known.

A Future Fair For All?

Indeed, Labour’s 2010 general election manifesto promised:

“We will support an active role for the independent sector working alongside the NHS in the provision of care, particularly where they bring innovation – such as in end-oflife care and cancer services, and increase capacity”

and further promised that:

“patients requiring elective care will have the right, in law, to choose from any provider who meets NHS standards of quality at NHS costs.”

The “Tony Blair Dictum”

The “Tony Blair dictum” essentially is that it doesn’t matter who provides care, so long as it is free to the patient. It approaches the perspective of a ‘reasonable member of the general public’ as somebody who does not particularly care how much his or her own personal healthcare services is costing the taxpayer “or increasing the deficit”. It is therefore quite a Thatcherite view of an individual, rather than a view held by a socialist.

This is an extract from a speech given by Rt Hon Tony Blair MP, The Prime Minister to a meeting of The New Health Network Clinician Forum on Tuesday 18th April 2006:

“…

Therefore thirdly, patients are being given a choice of NHS provider. So if they have to wait too long at one hospital or are dissatisfied with the standard of care, they can go elsewhere. This choice is already available in the private sector. Now it will be available in the NHS.

Fourth, there will be new independent providers encouraged in the NHS, of which the ITC’s are the first wave. Now this is being opened up to diagnostics, where the major bottlenecks often occur. In addition, where GP lists are full and areas are underprovided, new providers will, for the first time ever, be allowed to come in and provide GP services.

As a consequence of these reforms, there is then structural change to Strategic Health Authorities and PCTs, to streamline them so that they fit the purpose of a less centralised system and to focus them on helping the effective commissioning of care

The result of all of this is to try to create an NHS where there is not a market in the sense that consumer choice is based on an individual user’s wealth; but where there is the opportunity, on an equal basis, for users to choose and exercise power over the system that provides the service. It signals the move from a “get what you’re given” service where the patient falls into line with what the service decides; to one that is more a “get what you want” service moulded around the decisions of the patient. It rewards the producers well; but insists in return that it is the user that comes first. It mirrors the change from mass production to a customised service in the private sector.”

Sean Worth only this week at the RSA used this patient choice argument to justify the enactment of new legislation, “putting patients’ voices in control” and “public’s choices driving policies, not politicians in backroom deals.”

The overall intellectual property legislative framework for branding for “independent sector treatment centres” in this regard is very interesting. In English law, branding is protected by registered trademarks, such that goodwill to and the reputation of the organisation is protected. The branding is meant to be “shop window” of an organisation, and represents the “badge of origin”. In the NHS’ case, co-branding private providers’ suppliers brands with the NHS logo sets out a rather confusing message about the exact origin of NHS services which have been made available by private suppliers. It cannot be the case the “ethos” of private suppliers is the same as that of the NHS, in that private limited companies exist in law for the directors to maximise shareholder dividend.

In this particular context, the branding advice is very specific, for instance:

Remember: you cannot use the NHS logo on any materials which are not directly related to the provision of your NHS services. For all marketing materials that are co-branded with the NHS logo, you must use theNHS typefaces and colour palette.Your marketing materials must also support the NHS brand values and communication principles.

“I can’t believe it’s not the NHS”

Therefore, it seems that, at face value, the Coalition like the previous administration is allowing the patient to ‘shop around’ for the NHS services, and these NHS services are being made available.

THERE ARE MASSIVE ECONOMIC PROBLEMS WITH THE TONY BLAIR DICTUM, RECYCLED BY SEAN WORTH ABOVE.

Fundamental difficulties still arise from this type of scenario, and they’re all to do with information. Tim Kelsey and Paul Nuki might argue that “the more information the better”, but there are still significant policy issues here.

If the information cost of services is made available to the patient, then the accusation will come that patients are ultimately choosing their services on the basis of low cost not high quality; and furthermore the patient will simply get confused in trying to reconcile this with clinical advice from his or her own GP; and thirdly there is potentially a conflict-of-interest anyway between the Doctor and his/her patient about clinical need and cost.

If this information is not made available to the patient, then it is perfectly possible that a single provider can decide to become known for a certain procedure such as day case hernias, which just happens to be “low cost and high volume”. and this is where the problem of “cherry picking” comes in. It is perfectly possible for the private provider then to make a huge profit from such procedures, unknown to the taxpayer who is ultimately paying for these, as long as these private providers are awarded contracts (by submitting slick pitches on the basis of “integrated care” or “best value”). Tthe private provider is of course very happy because it can return a massive shareholder dividend to its investors, and in the long term the costs of running the NHS get much larger.

This is precisely what has happened in all other privatised industries, such as gas, electricity, telecoms, water, leading to a fragmented service, offering homogenous products where there is massive supplier strength in a crowded market (an “oligopoly”), where in fact there is little real competition. The idea of choice, in shopping in a supermarket or even in a patient choosing a NHS standard service, is fine IF the market is not distorted. Instead, an ability of a NHS patient to shop around will then be an artifact of how crowded the market is, and how much a clinical commissioning group will justify clinical decisions with the risk of facing expensive litigation suits in domestic and EU courts of law (which Monitor cannot protect them from, now that the NHS section 75 Regulations have finally been drafted officially.)

There is a huge problem with all of this. The biggest danger still remains about how, if left to its own devices, the market can steer to becoming contracted, which is why it is hardly surprising that the statutory duty of the Secretary of State to provide comprehensive healthcare has been removed, even if what remains strictly speaking remains “free-at-the-point-of-use”. That’s why politicians have become very adept at separating “universal” or “comprehensive”, from the “free-at-the-point-of-use” strands.

Therefore this little tub of “I can’t believe it’s not the NHS” may not be as innocuous as it first appears. The issue is of course the extent to which parliament wishes to throw the NHS to the private sector. However, this Government have made it very clear that their statutory instruments lock the NHS into a private competitive market unless in extreme conditions, paving the way for the destruction of the infrastructure of the NHS, as Oliver Letwin’s alleged remark, “The NHS will not exist any more”, can tragically become true.

Thank you very much for valuable comments on previous drafts of this article.

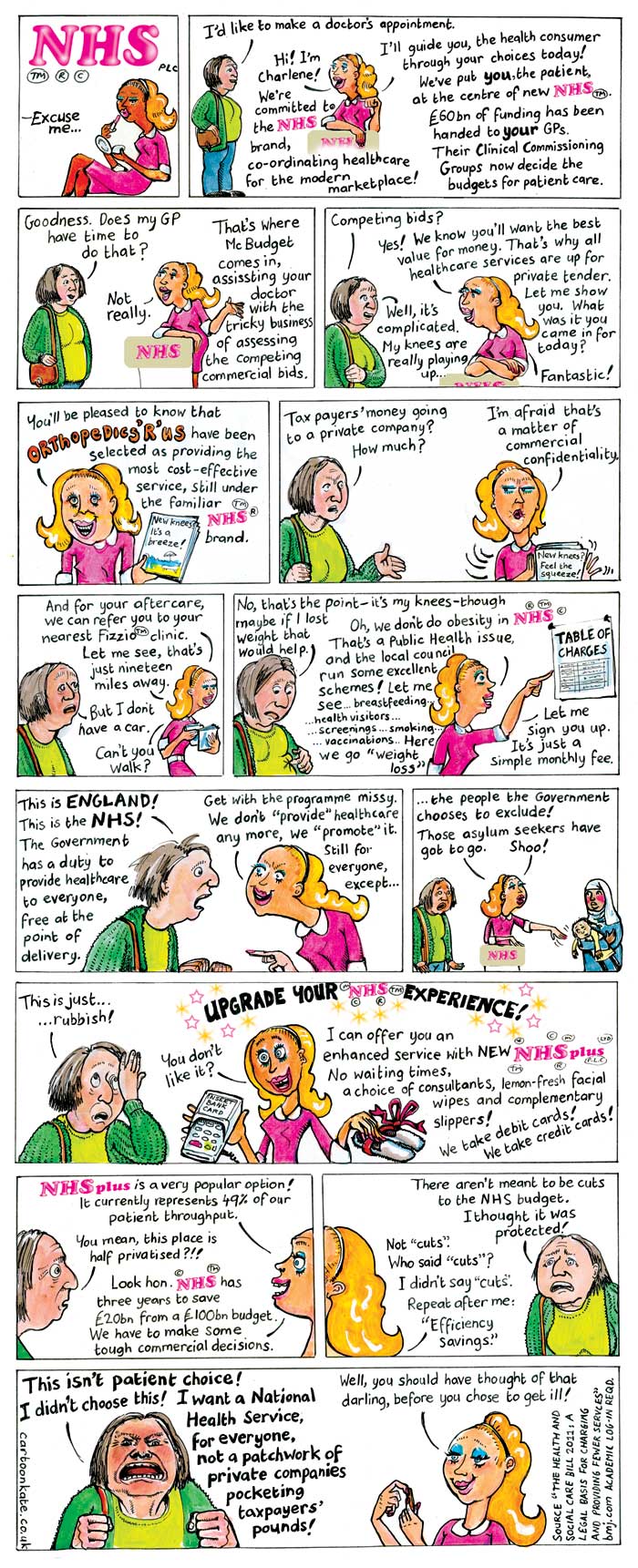

Thank you to “Cartoon Kate” for her brilliant cartoon about the NHS privatisation

Thank you to “Cartoon Kate” for her brilliant cartoon about the privatisation of the NHS. We spoke just now, and she’s given me permission very kindly to share this cartoon with you.

The original link to the cartoon is http://www.cartoonkate.co.uk/nhs-plc/.

This cartoon is really a Godsend for those of us who feel we’ve failed in getting our message across to the wider general public about why this satisfies the standard international and domestic published definitions of “privatisation”.

Kate is a very pleasant person, and I strongly encourage you to support her work here. She can be emailed using her ‘Contact us’ page, and can be reached easily on her phone number here.

Slide presentation version shared this afternoon:

Should we be choosing chocolates rather than picking cherries?

You are advised to read this article in bits, according to which parts interest you. If you would like to engage constructively in some of the issues here, I can easily be reached on my twitter thread @legalaware

Introduction

There are potentially very many false dichotomies in the debate over English healthcare: private vs public, efficient vs inefficient, etc. While we wait to halt the privatisation of the NHS, it might be better for our morale to think positively that some private healthcare providers are choosing different chocolates, rather than picking cherries, but ultimately the purpose of the State might be to aspire to cover all illnesses, irrespective of financial ability to pay, and this is of course a very admirable one. The problem is: in an unfettered market, the equilibrium will simply be the conditions which are most profitable for providers are ‘covered well’, but in the new-look NHS (“Neo NHS”), some conditions will be massively under-represented and could become very costly for CCGs covering these patients?

Whenever you introduce a market, you will always experience the phenomenon of “cherry picking”. The question in the short term must be: what do we do with the fact that certain companies will wish to pick their cherries, so that directors can fulfil their statutory duty under s.172 Companies Act [2006] to “promote the success of the company”, i.e. maximise shareholder dividend. For some reason, the electorate does not wish to be open about the privatisation of the NHS, even though market-oriented health care reforms have been high on the political agenda in many countries (e.g. Erik M. van Barneveld and colleagues, 2000). The response of the left tends to be a binary ‘boom-or-bust’ approach; for example, having the Act repealed, having no markets etc., and ideally ‘in moving forward, I wouldn’t start from here‘. The problem however is that we can all become trapped in ideology, and become attached to fundamental principles. Some would say that some issues are “clear red line” issues such as comprehensiveness or totality of the NHS, but, in light of the ongoing active discussions about rationing, it is clear that certain issues need to be confronted sooner rather than later. This article will consider how ‘cherrypicking’ has been addressed, and possible ways of dealing with it. It is only meant to be an introduction to this complicated issue, however.

Use of the term “cherry-picking”

One of the criticisms made about the NHS privatisation is that the outcome of the process will see some providers “cherry-picking” services. The issue about this term is that it sounds pejorative, even if this is your image of a bowl of cherries:

Legal origin of cherry picking as a concept

The legal use of the term “creamskimming”, in a different jurisdiction (the US), appears to have originated in a 1951 Supreme Court case, Panhandle Eastern Pipe Line Co. v. Michigan Public Service Commission [1951].The appellant Panhandle, an interstate gas pipeline company, launched a program to secure for itself large industrial accounts from customers already being served by the Michigan Consolidated Gas Company, a local distribution company franchised under Michigan law. The Supreme Court of the United States refused to grant Panhandle a purported “right to compete for the cream of the volume business” within Consolidated’s customer base “without regard to the local public convenience or necessity.”

Jim Chen has provided that the following definition of ‘cherrypicking’ should be used:

““Cream skimming” should be defined as “the practice of targeting only the customers that are the least expensive and most profitable for the incumbent firm to serve, thereby undercutting the incumbent firm’s ability to provide service throughout its service area.””

Chen quickly goes onto say the following:

“The unfortunate truth is that regulated incumbents have long exhibited a tendency to condemn lawful, desirable competition simply by invoking the pejorative label of “cream skimming.” Alfred Kahn diagnosed the urge long ago: “if one defines as ‘creamy’ whatever business is worth competing for,” one will reach the absurd conclusion that “all competition is by definition cream skimming.”

Indeed, at the time of another massive NHS reorganisation in 1974, Alan Reynolds writing in the Harvard Business Review observed from the same viewpoint:

“Whenever a monopoly or cartel pleads with the government to ban or restrain competitors, it invariably accuses the newcomers of skimming the “cream” and leaving the less profitable business to established companies.”

“Cherry-picking” as a political (and otherwise) device has been an on-running theme in the discussions over the Health and Social Care Act [2012]. Cherry picking (sometimes also referred to as cream skimming) is a term that generally refers to the act of selecting only the best or most desirable candidates from any group. As Mark Armstrong explains, “It is a common regulatory practice to “assist entry”, especially in the early stages of liberalisation.” In the context of healthcare provision, it is typically used to describe instances where private healthcare providers select patients which are of the highest value and lowest risk to them, referring less desirable patients, those with conditions likely to require more complex treatment, back to the NHS.

As the Health and Social Care Act introduces markets to many more areas of the NHS, cherry picking is likely to increase. As as this increases, public scrutiny of it is likely to increase, and it’s pretty likely that private suppliers are already organising their PR for this. Indeed, Alan Reynolds (1974) had advised the following to (presumably predominantly corporate) readers of his article in the Harvard Business Review:

“Newcomers accused of cream skimming should force their accusers to be quite explicit about how much cream there is, where it comes from, and where it goes. Where did the monopoly get the mandate to run this [] program. What are exactly are the objectives? Is there a better way to achieve them. Who audits the results? Without such substance, the cream-skimming cliché has about as much credibility as an unsupported accusation that competition is unfair. There are plenty of epithets for those who charge low prices, but they relatively merit attention.”

The importance of the regulator

Cherrypicking poses a difficult problem for the regulators – as predatory pricing should not be confused with improved competition in financial markets, and may not in fact be illegal per se in some jurisdictions. This has been a “known issue” for some time, see for example the memorandum submitted by Monitor, the “sector regulator” dated 19th July 2011:

There was also concern that the Health and Social Care Bill would enable private providers to ‘cherry pick’ routine and less complex healthcare services and interventions that are cheaper to provide and more profitable. The concern was that this would leave the NHS to deal with the higher-cost, more complex and long-term conditions with inadequate prices, causing the destabilisation of local hospitals. A proposal has now been included in the Bill to address this concern, which means that Monitor would be given a specific duty to set prices that reflect underlying costs, so there should no longer be any cherries to pick. Cherry-picking should not be an issue if NHS prices are designed to reflect complexity of treatment so that appropriate payments are made for both simple and complex services.

In his latest advice to 38Degrees, David Lock indeed refers to “cherry picking”:

“Private providers will seek, for example, cherry pick services which are relatively cost-effective to deliver may be able to put pressure on the commissioner to divide out those services from others on the grounds that the private provider can provide those services more economically or that to bundle up these services with other services amounts to anticompetitive behaviour. This is likely to be an area of intense debate within the NHS as private providers seek to use the (in places unclear) wording of the Regulations to put pressure on CCGs to divide contracts. Some CCGs may be able to resist this pressure but others are likely to succumb to this pressure. It follows that whilst the wording of the regulations does not place any duties onCCGs explicitly to divide contracts, in practice this happen for the reasons outlined above.”

So there is patently a debate to be had. History has provided that there can be a huge problem in effecting market entry, and the only way you can achieve anything like ‘good competition’ is to avoid a situation with only a few suppliers. Cited in Armstrong (2000), the privatisation of BT is noted.

“In Britain, the first competitor was explicitly granted favourable access to BT’s network, and in particular was made exempt from making any contribution to BT’s access deficit (see DTI, 1991, page 70):

“it is reasonable to exempt a new competitor [...] from the [access deficit] contribution in the early stages of its business development, in the interests of helping it get started. If this were not done, the ability of the newcomer to compete might be inhibited because of the economies of scale available to the incumbent and competition might never become established.“

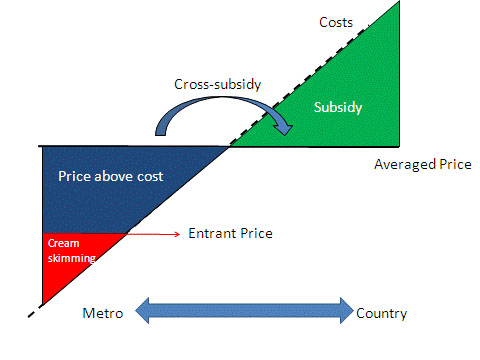

Cross-subsidies

A possibly way to address this is through the use of “cross-subsidies”?

As shown here (diagram produced originally in http://www.ictregulationtoolkit.org/en/Section.3545.html) this could be a mechanism of addressing a potential market failure, but a cross-subsidy may indeed itself be anti-competitive when a firm with market power prices services in less competitive markets higher so that it can have lower price for services it sells into competitive markets.

The issue of “cross-subsidies” has been addressed in other sectors: for example: “Incumbents complain about “cream-skimming” competition allowed by the cross-subsidies above. So, regulators assist incumbents with price rebalancing to meet competition, which generally increases line rentals so that call prices can fall. This is a politically sensitive process because raising access prices disadvantages the poorer users who make fewer calls; so some policy direction may be needed.”

But politically, does admitting there are cross-subsidies constitute a failure of the market? This is again where the patient may not be given complete information. Indeed, unless you happen to be medically qualified, you will not share the level of information a clinician may have in making a decision about your own care. Like all other aspects, it is quite possible that the general public, i.e. real patients, will not be involved in this discussion, but it does indeed happen in other sectors, for example:

Respondents knew that cross-subsidising goes on – at least to some extent – in other areas. They knew, for example, that they paid some additional, albeit unknown, amount in the supermarket to cover the cost of shoplifting, breakages and in-store damage to goods. They suspected that the cost of insurance premiums must allow for fraudulent claims. They were less aware that train fares include a subsidy to cover revenue lost through fare dodging, or that mortgage rates compensate lenders for defaulters, or that electricity and gas customers in rural areas are more expensive to service than those in urban areas but the cost is spread across all customers. There was no awareness at all of a cross-subsidy in the water bill.

Payment-by-results?

The Government has decided to tackle this through “payment by results”. As Crispin Dowler and Dave West have recently reported in the Health Services Journal,

“Commissioners may need to increase the prices they pay to NHS hospitals left with more complex workloads after other providers have “cherry picked” the easier patients, new Department of Health guidance shows.

… Rules introduced this year gave commissioners the flexibility to cut the tariffs they pay to such providers, but did not mandate increased payments to hospitals that are left with disproportionate numbers of complex and costly patients.

However, the guidance for 2013-14 appears to endorse above- as well as below-tariff payments.

“Commissioners will be required to base any decision to reduce tariffs on clear evidence which shows that the provider would be over-reimbursed at the national tariff rate,” it states. “They must also give consideration to the potential for other providers to be left with an altered, more costly, casemix which may therefore also require a funding adjustment.”

As was indicated in the draft document published in December, the final PbR guidance also includes a list of high-volume procedures that may be more susceptible to “cherry picking”.”

Conclusion

So, what should the response be from an organisation interested in socialism? There is no doubt that this discussion has advanced well beyond “whether it’s marketisation or it’s privatisation”. The legal instruments will come into force on 1 April 2013, and this article has no intention of proposing a campaigning thrust for ‘saving the NHS’. However, what has been presented here has been some indication of the language of ‘cherry picking’, what the potential issues about ‘cherry picking’ in markets might be, and how these might be mitigated against by the regulators. The problem is: in an unfettered market, the equilibrium will simply be the conditions which are most profitable for providers are ‘covered well’, but in the new-look NHS (“Neo NHS”), some conditions will be massively under-represented and could become very costly for CCGs covering these patients? Time will tell how this evolves.

Further reading

February 2000: Mark Armstrong (Nuffield College, Oxford OX1 1NF) Regulation and Inefficient Entry.

Department of Trade and Industry (1991), Competition and Choice: Telecommunications

Policy for the 1990s, London, HMSO.

Alan Reynolds. November – December 1974. A kind word for cream-skimming. pp.113-118.

Erik M. van Barneveld, Leida M, Lamers, Ren6 C.J.A. van Vliet and Wynand P.M.M. van de Ven. (2000) Ignoring small predictable profits and losses: a new approach for measuring incentives for cream skimming. Health Care Management Science 3: 131-40.

Statutory instrument SI 2013/057 on NHS procurement in England: amendment or annulment?

A Statutory Instrument is used when an Act of Parliament passed after 1947 confers a power to make, confirm or approve delegated legislation on: the Queen and states that it is to be exercisable by Order in Council; or a Minister of the Crown and states that it is to be exercisable by Statutory Instrument. 1.15 pm last Tuesday (5 March 2013) saw Andy Burnham MP, the Shadow Secretary of State for Health, go head-to-head with Norman Lamb (The Minister of State, Department of Health). Lamb was invited to comment on the regulations on procurement, patient choice and competition under section 75 of the Health and Social Care Act 2012.

The discussion is reported in Hansard.

Lamb describes an intention to ‘amend’ the legislation

Lamb explains:

“Concerns have been raised that Monitor would use the regulations to force commissioners to tender competitively. However, I recognise that the wording of the regulations has created uncertainty, so we will amend them to put this beyond doubt.”

The problem is that this statutory instrument would have become law automatically on 1 April 2013, and still promises to do so in the absence of anything else happening. The safest way to get this statutory instrument out-of-action is to ‘annul’ the law, rather than having the statutory instrument still in force but awaiting amendment. Experts are uncertain the extent to which statutory instruments can be so easily amended, while in force.

Most Statutory Instruments (SIs) are subject to one of two forms of control by Parliament, depending on what is specified in the parent Act.

Fatal motion

There is a constitutional convention that the House of Lords does not vote against delegated legislation. However, Andy Burnham has said the exceptional nature of the Section 75 regulations, which force all NHS services out to tender, meant he needed to table a ‘fatal’ motion in the second Chamber. Indeed, Lord Hunt later tweeted that this fatal chamber had forced a rethink on the original Regulations:

The main effect of delegated legislation being made by Statutory Instrument is that it is effective as soon as it is made, numbered, catalogued, printed, made available for sale, and published on the internet. This ensures that the public has easy access to the new laws. This statutory instrument (SI 2013/057:The National Health Service (Procurement, Patient Choice and Competition) Regulations 2013) is still available in its original form, with no declaration of its imminent amendment or annulment, on the official legislation website here.

The “Prayer”

The more common form of control is the ‘negative resolution procedure’. This requires that either the Instrument is laid before Parliament in draft, and can be made once 40 days (excluding any time during which Parliament is dissolved or prorogued, or during which both Houses are adjourned for more than four days) have passed unless either House passes a resolution disapproving it, or the Instrument is laid before Parliament after it is made (but before it comes into force), but will be revoked if either House passes a resolution annulling it within 40 days.

A motion to annul a Statutory Instrument is known as a ‘prayer’ and uses the following wording:

- That an humble address be presented to Her Majesty praying that the [name of Statutory Instrument] be annulled.

Any member of either House can put down a motion that an Instrument should be annulled, although in the Commons unless the motion is signed by a large number of Members, or is moved by the official Opposition, it is unlikely to be debated, and in the Lords they are seldom actually voted upon.

Indeed, this is exactly what happened. Ed Miliband submitted EDM 1104 on 26 February 2013, which currently – at the time of writing – has 183 signatures – with the exact wording:

“That an humble Address be presented to Her Majesty, praying that the National Health Service (Procurement, Patient Choice and Competition) Regulations 2013 (S.I., 2013, No. 257), dated 11 February 2013, a copy of which was laid before this House on 13 February, be annulled.”

The purpose of “amending” the legislation

Lamb later provides in his answer:

“Concerns have also been raised that competition would be allowed to trump integration and co-operation. The Future Forum recognised that competition and integration are not mutually exclusive. Competition, as the Government made clear during the passage of the Bill, can only be a means to improve services for patients—not an end in itself. What is important is what is in patients’ best interests. Where there is co-operation and integration, there would be nothing in the regulations to prevent this. Integration is a key tool that commissioners are under a duty to use to improve services for patients. We will amend the regulations to make that point absolutely clear.”

How the Government “amends” the legislation is clearly pivotal here. Integration is another “buzzword” in the privatisation ammunition. Colin Leys wrote in 2011:

“In the emerging vision of the Department of Health, however, integrated care has always been associated with the drive to enlarge private sector provision, and the Kaiser [Permanente] connection emphasised this. The competitive culture attached to integrated care in the Kaiser model, coupled with the keen interest of private providers in all integrated care initiatives, were constants, and put their stamp on official thinking about the future NHS market.”

A possible reason for why this emphasis on competition has failed is that in other markets, such as utilities, rail and telecoms, there is a strong case that competition has not driven down cost at all, because of shareholder dividend primacy. Another good reason for people in favour of the private market to discourage competition is that competition might even inhibit a drive to integration, and integration is strongly promoted by private providers (and, incidentally, New Labour).

What does the Act itself say about ‘annulling’ statutory instruments?

According to s. 304(3), “Subject to subsections (4) to (6), a statutory instrument containing regulations under this Act, or an order by the Secretary of State or the Privy Council under this Act, is subject to annulment in pursuance of a resolution of either House of Parliament.” So, at the moment, we are clearly in limbo, with parliament yet to pass a EDM, and new redrafted Regulations yet to appear. However, it is still a very dangerous situation, as the original set of Regulations is still yet to be enacted on 1 April 2013.

The legal issues in the statutory instrument (2013, No. 257) on NHS procurement in England

The key document in question is here.

In a nutshell, it has thrust private sector ‘competitive tendering’ in the procurement of NHS services into the limelight.

The legislature, as recommended by the executive, has an obligation to provide law that is clear and predictable, and the judiciary can only rely on the Acts on the statute books and any supporting discussions of what parliament might have intended. It is at the heart of parliamentary sovereignty that parliament can do what it wishes. There is, unfortunately, a large number of issues concerning this statutory instrument 2013 No. 257 concerning procurement in England. These embrace a plethora of commercial and legal, not just political, considerations, which do need to be discussed as a matter of some urgency in the public interest. Such discussion will be to the benefit of all involved parties.

The judiciary must have a clear understanding of how this law was arrived at, for it to interpret the ‘intention of parliament’ when any disputes arise as they indeed will. To help it, it has the Bill and Act itself, as well records in Hansard. The case and statute law, both domestic and EU law, have a recent history in effecting English NHS health policy, but only in as much the NHS has encroached upon ‘undertakings’ and ‘economic activity’ in EU law. The Health and Social Care Act (2012) has changed the legal climate substantially; indeed, the ambit of competition is thrown very wide indeed, as reflected in Regulation 10.

Section 75 of the Health and Social Care Act has firmly enmeshed the Act in competition legislation, parallel to but distinct from previous legislation such as the Public Contracts Regulations (2006). However, the adoption of key concepts and themes from the European law, voluntarily by the English legislature as proposed in the statutory instrument, makes it rather unclear as to the actual ‘direction of travel’. It as if Parliament has wished to enmesh the NHS in European competition and procurement law, without any democratic scrutiny. The aforementioned statutory instrument is particularly vague on the precise functions of Monitor in the distinct phases of award and execution of procurement, does not map out how Monitor is to function on behalf of key stakeholders in the NHS along with other regulatory processes (such as judicial review or the health ombudsman), and how precisely this English legal framework will operate alongside other approaches (such as the UNCITRAL Model law, European regimens, and World Trade Organisation).

Critically, it seems quite mysterious how overall this particular method was chosen (formal tendering, as opposed to less structured methods of competitive tendering such as requests for proposals and quotations, or single-source procurement), when the discussions in the lower and upper Houses of Parliament did not heavily lean in this direction in the first place. (Such methods are extensively discussed in ‘Regulating Public Procurement: National and International Perspectives’ (2000) Sue Arrowsmith, John Linarelli and Don Wallace Jr. Kluwer Law International). This obligatory competitive tendering mechanism for the majority of tenders is a robust method of making sure as many contracts are awarded to the private sector as possible. There would be nothing to prevent parliament from legislating for a minimum of NHS services to stay in the NHS, as that would not offend any law in Europe; it does not distort the market, but for public policy reasons could easily be argued to have a legitimate reason. For example, if a key provider, e.g. of blood products, went bust, this could be the detriment of the entire service, and protection for such a service can easily be justified under statute.

Some specific points which are particularly noteworthy are raised in the Appendix.

APPENDIX

Regulation 3

3 (2)(b): “treat providers equally and in a non-discriminatory way, including by not treating aprovider, or type of provider, more favourably than any other provider, in particular onthe basis of ownership.”

It is quite unclear what this is driving at, and whether equality of providers is indeed a primary aim of the procurement process. For example, UNCITRAL model law on procurement of goods, construction and services lists this as an objective in the preamble to the law, but the Guide to Enactment suggests perhaps it is a subsidiary role. Cases such as Fabricom case (Fabricom SA v Belgium (Judgment Joined Cases C-21/03, C-34/03, 3 March 2005) are particularly helpful here.

3(b) What does “best value” in this sector indeed mean? Typical considerations such as “value for money”, as well as social, technological, environmental and various other non-price considerations, need to be discussed at some point. Again, this is essential if the law and guidance for the NHS procurement is to have adequate clarity. The point is not so much playing party-politics about grinding this legislation to a halt with an intellectual ping-pong, but it is helpful, if this clause is to be included in this statutory instrument, to understand what is in parliament’s mind for later disputes to be resolved. Presumably Monitor have begun to think about this as they hope to issue specific guidance on this?

3(4)(c) “allowing patients a choice of provider of the services” – as drafted it is unclear whether the true beneficiaries of the choice of providers are the patients themselves or CCGs (the relevant bodies); the relationship between actual patient choice and vicarious choices made by the CCGs is not addressed in this statutory instrument.

Regulation 4

Transparency for contract opportunities. This is indeed helpful to provide a rough check on how contracts are being awarded, but it has to be conceded that the public will be largely none-the-wiser as they will perform functions under the NHS logo (unless parliament requires the full identity of providers to be disclosed at the point-of-use for any particular patient.)

Regulation 6

This regulation, as drafted, is only confined to conflicts between purchasers and suppliers in the NHS, but a purpose of clauses such as this in other jurisdictions has been to address wider conflicts-of-interest, such as political donations. Although it may not be desirable to extend the ambit of discussion here too widely, some consideration should be made to how this might relate to other existant laws concerning bribery currently in force in England, for example?

Regulation 7

“Framework agreements”, which are not in fact ‘necessary’ will require in due course much greater detail if they are to be included. They certainly require, pursuant to Stroud, some scrutiny. How many suppliers will be involved in such agreements, as this relates to a complex interplay between operational efficiency, security of supply and the scope of competition? The question has to be why they have been imported from EU procurement law voluntarily, when there is actually no obligation to. It would be helpful if parliament could provide some indication of the processes and purpose of any shortlisting in the operation of these framework agreements, particularly in relation to relevant national policy considerations and disclosure of relevant criteria?

Regulations 13-17: Monitor (Investigations, declarations, directions and undertakings)

Ideally the outcome should be clear rule-based decision-making systems that limits the discretion of procuring entities. Monitor will have to have to explain this in due course, but no mention even is made of the types of issues which Monitor might have to face (e.g. fraudulent information in the bidding or execution phases, mechanisms of correcting any errors, late tenders.)

Competition Regulations issued under Section 75 of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) will lock CCGs into arranging all purchasing through competitive markets

Prior to this reorganisation costing billions, the NHS had been one of the most cost-effective health systems in the developed world, according to a study published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Public satisfaction with the NHS reached record levels in March 2011; writing on the BMJ website, Prof. John Appleby said 64% of people were either “very” or “quite” satisfied with the NHS. Now, very shortly, the Regulations which will govern the actual operation of the new NHS market will be passed under Section 75 of Health and Social Care Act [2012], in particular s. 75 (3a):

An ethos of collaboration is essential for the NHS to succeed

As a result of the Health and Social Care Act, the number of private healthcare providers have been allowed to increase under the figleaf of a well reputed brand, the NHS, but now allowing maximisation of shareholder dividend for private companies. The failure in regulation of the energy utilities should be a cautionary tale regarding how the new NHS is to be regulated, especially since the rule book for the NHS, Monitor, is heavily based on the rulebook for the utilities. The dogma that competition drives quality, promoted by Julian LeGrand and others, has been totally toxic in a coherent debate, and demonstrates a fundamental lack of an understanding of how health professionals in the NHS actually function. People in the NHS are very willing to work with each other, making referrals for the general benefit of the holistic care of the patient, without having to worry about personalised budgets or financial conflicts of interest. It is disgraceful that healthcare thinktanks have been allowed to peddle a language of competition, without giving due credit to the language of collaboration, which is at the heart of much contemporary management, including notably innovation. (more…)

Andy Burnham vows to repeal the Health and Social Care Act, and to reverse Part 3

Andy Burnham will repeal the Act, but is due to establish Labour’s official position at Conference later this week.

He answered my straightforward question about the Health and Social Care Act (2012) with a simple answer, at the Fabian Society Question Time this evening, hosted by Alison McGovern MP, and a panel also including Owen Jones, Dan Hodges, and Polly Toynbee. I had a very nice chat with Andy at the end, and Andy seemed to be quite impressed that I had read the entire Act carefully ‘from cover to cover’.

Andy reinforced his belief that the Act would be repealed, but he wanted the NHS to further a spirit of collaboration. There’s been a question about, even if the Act is repealed, there are genuine questions about which policy planks might go into reverse. I feel it is unlikely that NHS Foundation Trusts will be revised, and I don’t think commissioning will be done away with, though I am uncertain about the future of ‘clinical commissioning groups’ (“CCGs”). Andy’s indication that existing structures might be asked to do different things gives Andy a bit of lee-way as to the working relationship between NHS Foundation Trusts, or CCGs (or whatever they turn out to be).

Part 3 will be first in the firing line, the Act will be repealed, and the NHS will go back to a system based on collaboration consistent with its founding principles. Critically, this Part of the Act establishes the legislative framework for the sector-regulatory body and its functions, “Monitor”, competition and licensing. My guess is that Andy Burnham MP will find a way for the NHS not to be a free-for-all in an unfettered market. My impression is a lot depends on escaping the EU definition of “undertaking” in EU competition law.

The NHS prior to this Act had been immune from a discussion of competition in that the NHS had from this previously is that a regulatory authority for competition, the Office for Fair Trading (“OFT”) did not consider that any public bodies involved in the purchasing or supply of goods or services within the NHS were “undertakings”, and therefore were not subject to action under the Competition Act. In other words, any involvement of these bodies was for “non-economic purposes”. This was reinforced by the EU in relation to a Spanish healthcare case FENIN v Commission in 2006, on the basis that the system concerned operated on the principle of ‘solidarity’. They have therefore exposed some services (which previously would have been provided in-house) to a scenario where they will be considered for competitive tendering. The extension of Any Qualified Provider (albeit with a more limited, phased implementation from 2012) to a wider range of services, and the distancing of the state from acute sector provision in the form of foundation trusts could conceivably weaken the argument against healthcare provision being for “non-economic purposes”, particularly when individual service lines are considered.

This is highly significant, I feel, that Andy Burnham could be steering the NHS away from being run for ‘economic purposes’, and this could be the passport for Andy for not becoming enmeshed in lots of complicated domestic and EU law. As it happens, I have a real feeling that European lawyers would prefer not to enmeshed in a complicated discussion about private provision in healthcare, as they feel that competition law is best applied to pure private or commercial entities not involved in social/healthcare policy.

As it stands, the Health and Social Care Act (2012) is a complex interplay of domestic and EU law in the disciplines of company law (including mergers, financial assistance), commercial law, procurement law (including public contracts), regulatory law, insolvency law (particularly administration). However, the law, albeit at nearly 500 pages, does have some notable omissions, such as what happens if a CCG ‘trades’ while going insolvent. Law would have to clarify consider, in its capacity as a ‘body corporate’, whether the CCG were still capable of wrongful or even fraudulent trading.

A complex interplay of factors now determines the future of the NHS

2011 was the first full year of the introduction of the full privatisation of the NHS, and a year of the steepest decline in public satisfaction in the UK, in the first full year of the Coalition after all parties had failed to win outright the 2010 UK general election. There’s a very important notion in finance and business that the markets are very sensitive to dividends. That is why for example other investors will be interested in the corporate ‘health’ of the economy, with the shareholder dividend as a potent signal in the market, for example.

I spent this afternoon spending a couple of hours at the Socialist Health Association Annual General Meeting. Obviously rules provide that I cannot blog openly about what was discussed, partly because I cannot remember exactly what was discussed. Imagine my joy when I emerged from the Friends Meeting House on Mount Street to find that @Putneydebates has let me know that Ed Miliband had made an announcement on the NHS. This was all however relatively relaxing compared to having read all 500 pp. of the new Health and Social Care Act for an informal chat I was to have with Dr Lucy Reynolds later last week.

I have indeed had trouble in finding the actual announcement. This is the best I could find:

Please note the use of the word “reverse”. This is because Labour are intensely edgy, because they do not know the exact state of the economy on May 8th 2015. If the Conservatives inherited a “mess” due to a massive financial stimulus to the banking industry to stop an outright depression, the mess potentially handed to the governing party/parties in May 2015 could be far worse. When Labour lost the election in 2010, the UK economy was actually growing. It then predictably entered a ‘double dip recession’ earlier this year due to a lack of a Keynesian stimulus and strangulation of consumer demand (as people in the public sector had less money, and VAT went up).

Andy Burnham has previously promised to repeal the Act (as he argued for a long time in Parliament). This is not in any dispute, though critics wonder about, having made the promise, what a realistic timescale for the repeal might be. Burnham is aware that, by 2015, more of this ‘top-down reorganisation’ (which nobody as such voted for), will have been implemented. We may still be in recession in May 2015, therefore it would be impossible for Labour to embark on a costly programme for the NHS. The facts are that Labour has introduced commissioning in some form, and Foundation Trusts, but the extent of private ownership, the elaborated on commissioning, means that there are strands of policy which are indeed deeply engrained. Furthermore, it is certainly not clear what the state of the UK economy will be in May 2015; the UK economy entered a double-dip earlier this year, and borrowing is increasing, therefore Labour’s room for manoeuvre is genuinely limited.

There is no doubt that there was much distress amongst some about the UK Labour Party’s future direction on the NHS last night. The problem is that NHS has had so many operations, some plastic genuinely to make it function, some reconstructive to make it appear more attractive, that it now runs the risk of being totally unrecognisable as a hybrid public-private entity. The general public might ‘blame’ the Coalition for introducing these reforms under duress, against opposition of all the Medical Royal Colleges, in particular the Royal College of General Practitioners, under the leadership of Clare Gerada, and the British Medical Association. Some of the public even blame New Labour for introducing the marketisation of the NHS (allegedly), and some blame the BBC particularly (although the topic is incredibly complex, and various interests have been mooted as possibly for why the BBC has preferred to keep silent on the issue as the Bill went through parliament and the House of Lords). However, a growing corpus traditional Labour voters feel that Labour has betrayed its roots on a NHS, truly national, free-at-the-point of use, and paid for entirely out of the taxpayer and which does not make a profit. Indeed, aspects of the denationalisation, marketisation and privatisation can indeed viewed on a spectrum of abolition of national health bodies (such as the Health Protection Authority and National Patient Safety Agency), pricing and competition strategies, procurement contracts which have to obey UK and EU competition law, the introduction of GP Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), administration and rescue of failing trusts, mergers of clinical entities, and acquisitions of State hospitals by private entities. Some of this can be unpicked, some of it is not so easy to unpick.

The extent of private involvement can be unpicked, setting caps by Government. These budgets proposed for the CCGs are sufficiently high for the Public Contracts Regulations 1996 to kick in, and because of the way that a financial undertaking is defined by Europe in case law, for EU competition law to kick in (such as article 101). Corporate restructuring and financial restructuring of failing entities are a complicated science, and could apply to CCGs and the new model army of the NHS Foundation Trust; financial assistance is a consideration, and, whilst the sector regulator Monitor will be heavily involved, also embroil in addition to the Health and Safety Act (2012) the Companies Act (2006) and Insolvency Act (1986).

Andy Burnham MP was forced yesterday afternoon to shout ‘repeal, repeal, repeal’ on Twitter, for instance:

Andy had also made this very clear in the Houses of Parliament earlier this year in the ‘opposition day’ debate on the NHS:

In this video, Andy Burnham does confirm his intention to repeal the Act ‘in its entirety’, ‘as it is a defective piece of suboptimal legislation which has saddled the NHS with a complicated mess” and “unintelligible”; Burnham adds further “it would be irresponsible to leave it in its place”. Ed Miliband, however, has previously mooted that he might reverse clinical commissioning, but Miliband’s current position on this is unclear. To reconcile the fact the Act will be repealed but there will be a change of direction under Labour, Burnham states that “organisations will be asked to differently”, implying that the structures being abolished in the current tranche in reforms will remain abolished (i.e. PCTs and SHAs), but there will be less competition in the further evolution of the Act which might not necessitate a new full-blown act and not require yet another extremely costly “top down reorganisation”, as it is said that morale in most of the NHS is now actually extremely poor.

There is no doubt that there has to be further documented guidance on the investigative powers of Monitor, although it is true to say the onus will be on the sector to report issues (as similar for the FSA and OFT), but CCGs will need to have legal guidance about defending possible legal claims for judicial review or breach of contract in procurement contracts for enforceable legal rights. According to s.10(1) Part 2 Schedule 1A of the Act, a CCG is a ‘body corporate‘, which is extremely fortunate as the default position would have been a traditional legal partnership under the Partnership Act (1890) s.1. Whilst many CCGs may view themselves as businesses, many have not chosen to become private limited company under law; however legal clarity is indeed needed about the liability of the body corporate of the CCG in this particular case, as for example private limited companies have limited liability but traditional partnerships do not. It is patently clear that CCGs, which might still outlive this political drama, will need advice on, and more resources for, the management and legal operations of their businesses, whilst Labour struggles the ‘best’ of clinical commissioning. Labour may also have to work closely with firms such as KPMG and KcKinsey and Company, with the Coalition, in the meantime to construct a ‘risk register’ regarding issues faced by CCGs in real life (such as ongoing problems with contracts or staff wishing to resign or being made redundant). Labour also has to revisit the issues, even having repealed the Act, at an operational level to address rationing-by-cost which it has traditionally opposed, as for example shown in cataract surgery.

This has now turned into a political mess, and Labour as far as I can tell is still fully committed to getting rid of the Act. This would send out a very positive message from the Labour ‘command and control’ centre to its members and potential voters, but Labour needs to resolve as to whether this might spook out corporate investors through for example dividend signalling described above. However, whilst yesterday afternoon was ‘not great’, at least Labour appears to be willing to have a clear debate about this. Andy Burnham has asked the Coalition ‘to be honest about its true intentions about private involvement in the NHS’, and it would help all concerned, especially those in the NHS (including doctors particularly GPs, nurses, other healthcare professionals) members of the public, lawyers and management consultant firms, if Labour could be categorically repeat in a speech that (a) the Act will be repealed, (b) some indications about which strands of it (some are deeply enmeshed) will remain in situ.

Monitor has much work to do to produce a cogent analysis of pricing in healthcare

Monitor is in its infancy, but, pardon the pun, I would like to describe an example of childbirth to explain the mountain of problems that the new privatised NHS is yet to experience. Consider this a steep learning-curve that not many of us voted for at the last election.

“The new NHS provider licence: consultation document” was issued by Monitor on 31 July 2012 with a deadline for responses determined as 23 October 2012. According to section 5.1 of this Document on pricing,

“One of Monitor’s new functions will be to set prices for health care services funded by the NHS.Accurate pricing is essential to ensure that providers are paid appropriately for services they provide to patients. Accurate pricing information helps GPs, commissioners and providers to plan and budget for health care services to meet people’s needs. Pricing can also be used to encourage providers to improve the quality of services for patients, and to increase the efficiency with which services are provided. If providers are not properly reimbursed, this can reduce the quality and efficiency of care they offer and may, in some circumstances, threaten the sustainability of their services.”

Pricing is pivotal in markets, and will obviously therefore be expected to the subject of considerable scrutiny by competition regulatory authorities. In future, Monitor will be responsible, in partnership with the NHS Commissioning Board, for setting prices for NHS services.Indeed, according to a statement produced on 20 June 2012,

“The Health and Social Care Act 2012 makes changes to the way health care is regulated in order to strengthen the way patients’ interests are promoted and protected. Monitor’s role will change significantly as we take on a number of new responsibilities. We will become the sector regulator for health care, which means that we will regulate all providers of NHS-funded services in England, except those that are exempt under secondary legislation.”

Take for example the cost to the taxpayer of a provider delivering a baby – not the antenatal or postnatal packages, but the cost of the actual labour and peri-partum process (“the package”). Like any other “product” in the market, a supplier will have to price its product carefully, to ensure that it offers a competitive price, but especially to ensure it does not price itself out of the market by being too costly. The price of “the package” might be determined through a number of different ways.

- Premium pricing (also called prestige pricing) is the strategy of consistently pricing at, or near, the high end of the possible price range to help attract status-conscious consumers. People might buy a premium priced product because they believe the high price is an indication of good quality.

- Cost-plus pricing is the simplest pricing method. The firm calculates the cost of producing the product and adds on a percentage (profit) to that price to give the selling price. This method although simple has two flaws; it takes no account of demand and there is no way of determining if potential customers will purchase the product at the calculated price. You only need to consider the complexity of doing the calculation for the package”, e.g. will the provider use cheap epipdural needs for the anaesthesia, will a foundation year doctor (who is cheaper) perform most of the medicine compared to a specialist registrar (who is more expensive, but more experienced, especially in dealing with medical emergencies).

- Value-based pricing – a price based on the value the product has for the customer and not on its costs of production or any other factor.. The relevant issue is how much would you be prepared to have provider A deliver your baby? This is a subjective issue, not easy to predict.

The problem with premium pricing is that providers can collude lawfully to set their prices as high as possible between them. Price fixing is illegal under Article 101 TFEU of the European Union:

Article 101

(ex Article 81 TEC)

1. The following shall be prohibited as incompatible with the internal market: all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market, and in particular those which:

(a) directly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditions;

(b) limit or control production, markets, technical development, or investment;

(c) share markets or sources of supply;

(d) apply dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage;

(e) make the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts.

2. Any agreements or decisions prohibited pursuant to this Article shall be automatically void.

3. The provisions of paragraph 1 may, however, be declared inapplicable in the case of:

– any agreement or category of agreements between undertakings,

– any decision or category of decisions by associations of undertakings,

– any concerted practice or category of concerted practices,

which contributes to improving the production or distribution of goods or to promoting technical or economic progress, while allowing consumers a fair share of the resulting benefit, and which does not:

(a) impose on the undertakings concerned restrictions which are not indispensable to the attainment of these objectives;

(b) afford such undertakings the possibility of eliminating competition in respect of a substantial part of the products in question.

It has been incredibly hard to prove price-fixing, but numerous examples exist.

For example, the Daily Mail recently reported price-fixing at the petrol pumps:

“Motorists are being ripped off by profiteering oil companies and speculators, MPs suggested yesterday.They demanded an inquiry into allegations of price-fixing at the pumps, and called for the Government to replace its planned fuel duty rise with a windfall tax on oil company profits.

And last year they reported on the price-fixing of milk:

“Supermarkets and dairy firms have been fined almost £50million over price rigging on milk and cheese that cost families £270million. The collusion put up the price of milk by 2p a litre – 1.2p a pint – and added 10p to the cost of a 500g block of cheese. The punishment was announced by the Office of Fair Trading, following an investigation triggered by whistle blowers at the Arla dairy company. First revealed by the OFT in 2007, the ‘Great Milk Robbery’ took place in 2002 and 2003. But only now has a fine of £49.51million been handed down.”

For Monitor, regulating this will be a mammoth task. Private health providers have much scope for setting between them the most profitable way of delivering the patient’s baby, and it is a great market to be in: the country will never be short of a need for providers of safe deliveries of babies. Whilst other metrics might be important to the clinician, such as mortality or morbidity (infection rates), it could be that private providers are distinguished most themselves by the least cost to a GP practice. Or, it could be that people are genuinely fickle about not caring about who picks up the tab, but the preferred private provider might provide “extra frills”, like en-suite TV with 80 channels.

The problematic issue is what happens if an unconventional problem comes out-of-the-blue. The mother might experience a rare type of headache, such as trigeminal autonomic neuralgia, and there is effectively no “patient choice” involved, save for the GP having to refer the patient to a specialist unit like Great Ormond Street Hospital. You will notice here that the quality of patient choice is nothing to do with the innovation of the private health provider, nor indeed how “competitive” the market of private providers of childbirth is: it is entirely to do with the skill of the clinician in making a rare diagnosis, and having the astuteness of having a specialist unit such as Great Ormond Street Hospital deal with it safely, whatever the cost. You must note that I give this example of TAN at GOSH completely at random, and any similarity to a real-life scenario is of course completely unintentional.