Home » 2014 (Page 5)

Yearly Archives: 2014

Why are peer support groups for people living well with dementia so relatively under-researched?

There has been in recent years a developing cross-party consensus on the ‘personalisation agenda’ in health and care, despite a growing army of serious critics. Individualism however co-exists in policy with ‘collective spirit’, the latter for example most notably in the policy plank known as “dementia friendly communities”.

People helping each other is a good thing. And this is, of course, motherhood and apple pie stuff.

For example, Vissier and colleagues (2008) found, in their investigation, that only staff members who received peer support reported greater skills and knowledge, consistent with previous research findings demonstrating that effective peer support for practitioners can be very useful (Edberg and Hallberg, 2001).

It has also been argued that it can be helpful to prepare for “possible personal and emotional responses in conducting clinical research in dementia”, for instance by ensuring that peer support or supervision are available (Ablitt, Jones and Muers, 2009).

The opening paragraph of a paper looking at ‘support groups’ states openly that it did not wish to look at the issue of the composition of support groups in their study (Snyder, Jenkins and Joosten, 2007):

This survey did not attempt to determine who is appropriate for a support group or who may or may not benefit. Indeed, the study sample is biased by the sole inclusion of those who volunteer to attend a sup- port group and continue participation in the group because of some presumed positive experience. This survey does, however, provide insight into why participants continue to attend their group and what aspects of the experience are most valuable.

It is totally unsurprising that the group that has been researched the most comprehensively in peer-peer support comprises caregivers (e.g. Greenwood et al., 2013), although there has been excellent research recently published on volunteering mentoring schemes (Smith and Greenwood, 2014).

We have all seen the hyperbolic claims of wishing to improve global research.

For example, Alzheimer’s Research UK earlier this year made the following point.

The G8 Dementia Summit in December 2013 was effective at galvanising the international community and promising clear and decisive action to tackle dementia. The Summit saw international leaders launch the ‘Global Action Against Dementia’ initiative with the stated the aim of finding a disease modifying treatment or cure by 2025.

And, yes, a lot of money does get pumped into activity which is cellular-related.

But men are not simply collections cells in Petri dishes.

I was immediately attracted the other day to a Facebook group called the “Young Onset Dementia Group”. It’s here.

The Dementia Alliance International (DAI) is a non-profit group of people with dementia that seeks to represent, support, and educate others living with the disease. DAI provides an international and unified voice of strength, advocacy and support in the fight for individual autonomy and improved quality of life for people with dementia.

The DAI gave a talk at the Alzheimer’s Disease International conference held in Puerto Rico this year May 1-4 2014. Their slides are helpfully uploaded here.

Online support groups have become a formidable force. Such “self-help groups” moderated by people with dementia and others; there are no caregivers. They can be an alternative to local support groups that don’t meet their needs, or in absence of a local group. Increasingly, people with dementia turning to social media to connect with one another.

Here is one experience from this group:

With just a couple of days to go, it gives, for example, details of a survey by the National Health and Medical Research Council. They looking for input from people diagnosed with dementia as well as care providers, medical practitioners, family and friends. If you have a few minutes spare and you’re Australian, please complete their survey because telling them what matters to you is so important.

Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer) has written about it here. Kate, of course, will be known to very many of you as a champion of change in Australia – and around the world, living well with dementia as a ‘consumer champion, the first ever consultant living with dementia appointed by the influential charity Alzheimer’s Australia.

Kate is well known for her campaigning for issues which people living with dementia wish to lead on. She is heavily AGAINST tokenistic involvement, as her powerful article on stigma and dementia-friendly communities in the prestigious Dementia Journal recently illustrates.

Every month the DAI meet for “Café Le Brain” – an online Memory Cafe that uses video conferencing technology to bring people together from far away. Together, they enjoy conversation, new ideas, support, and some fun. People living with and without the symptoms of dementia are welcome to attend.

The date of the next meeting is Wednesday, November 19, 2014, with a start time: 1 p.m. in Adelaide, Australia; 12:30 p.m. in Brisbane; 10:30 a.m. in Perth; 1:30 p.m. in Sydney; 11:30 a.m. in Tokyo.

If you’re eligible to join, please go to their EventBrite page here.

The Café runs for approximately 90 minutes. To find out the start time in your city, click here. The hosts of that Café will be, on this occasion, Kate Swaffer, Secretary of Dementia Alliance International, Mick Carmody and Gayle Harris, Dementia Alliance International members.

In all honesty, however, it has struck me how there are peer-support groups, fairly well researched (but not extensively researched), where the peers are Doctors or caregivers; but there is virtually no published research on people living with dementia peer mentoring other people living with dementia. This is of course a complete travesty.

For a start, large corporate-like charities in dementia are pump priming lots of money every day into glossy reports on loneliness. And yet the money that goes into high quality in living well with dementia sees this discipline as a very impoverished relation while the never-ending searching for cures that don’t work continue.

But peer support for people living well with dementia is important.

Such networks have worked particularly well for people living with young onset dementia. A number of well known groups are helpfully listed on a “Young Onset Dementia UK” website page.

“Truthful Kindness” (@TruthfulKindnes) is fast becoming a trailblazing leader. Her blog on living with dementia symptoms is widely read. Her “Person with dementia experience” is widely read.

These networks are not new, but operational difficulties in ownership of such groups have long been a problem. Such groups can easily be ‘harvested’ by people not living with dementia. They are ripe pickings, for example, by large corporate-like charities, and indeed Big Pharma. Notwithstanding that, there has been a long and distinguished past for example the “Dementia Advocacy and Support Network International” or DASNI).

Chris Roberts (@mason4233), after a protracted diagnostic experience, was eventually given a diagnosis of mixed dementia. Chris continues to share his observations of that experience of diagnosis itself in public, which has been of huge interest not only to others who’ve found themselves ‘in the same boat’. But this experience should also shame the medical profession into making the process of disclosure of a possible diagnosis of dementia much better than it currently appears to be from many service users of the health service.

And Chris mentions here the improvement in his own wellbeing from participation in “Dementia Friends”, an initiative where Chris gives information sessions on what dementia is to all members of the public; and, also, Chris speaks fondly of his participation in “Dementia Mentors”, a peer support online forum for people living with dementia, as well as his involvement with the Dementia Alliance International, where he is indeed a Board Member.

Both these videos were filmed by me at the recent Alzheimer’s BRACE event, “Hope for the future”, which took place in Bristol earlier last week.

I feel it is likely there is going to be much interest in peer support groups for people living well with dementia, whether corporate-like charities wish to research it or not. It’s going to be essential that the research field doesn’t compartmentalise themselves into silos. For example, a open paper entitled ‘Personalisation vs friendsourcing’ from makes for very interesting reading:

“When information is known only to friends in a social network, traditional crowdsourcing mecha- nisms struggle to motivate a large enough user population and to ensure accuracy of the collected information. We thus introduce friendsourcing, a form of crowdsourcing aimed at collecting accurate information available only to a small, socially-connected group of individuals. Our approach to friendsourcing is to design socially enjoyable interactions that produce the desired information as a side effect.”

Further readings

Ablitt A, Jones GV, Muers J. Living with dementia: a systematic review of the influence of relationship factors. Aging Ment Health. 2009 Jul;13(4):497-511. doi: 10.1080/13607860902774436.

Edberg, A., & Hallberg, I. R. (2001). Actions seen as demanding in patients with severe dementia during one year of intervention: Comparison with controls. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 38, 271–285.

Greenwood N, Habibi R, Mackenzie A, Drennan V, Easton N. Peer support for carers: a qualitative investigation of the experiences of carers and peer volunteers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013 Sep;28(6):617-26. doi: 10.1177/1533317513494449. Epub 2013 Jun 30.

Smith R, Greenwood N. The impact of volunteer mentoring schemes on carers of people with dementia and volunteer mentors: a systematic review. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2014 Feb;29(1):8-17. doi: 10.1177/1533317513505135. Epub 2013 Oct 1.

Snyder L, Jenkins C, Joosten L. Effectiveness of support groups for people with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: an evaluative survey. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2007 Feb-Mar;22(1):14-9.

Visser SM, McCabe MP, Hudgson C, Buchanan G, Davison TE, George K. Managing behavioural symptoms of dementia: effectiveness of staff education and peer support. Aging Ment Health. 2008 Jan;12(1):47-55. doi: 10.1080/13607860701366012.

Decisions in different types of dementia

Decisions are fundamental to our lives.

Decision making is a fundamental and complex skill which is crucial at any age. We all have to face decisions regarding their health care, medical treatment, retirement, housing, transport, and finances, for example.

We not only have to consider the benefit of a decision for their current living situation, but also to anticipate the consequences of decisions of such actions in the nearer and farer future. We need to hold the decision in my memory for long enough to think through strategically the options, and be able to action an outcome.

Everyday life requires numerous and fast decisions. Often these decisions have an uncertain result. Wrong decisions may thus have severe consequences in several domains.

Disturbances in an ability to make decisions or to anticipate the possible consequences of decisions can result in massive problems.

In the last decade in cognitive neuroscience and cognitive neurology, there has been an increasing interest to investigate neural basis of decision-making abilities and disturbances both in healthy subjects and to people where there has been some disruption.

But we have been able to build up a coherent picture of this using neuropsychological and neuroimaging techniques.

An assessment of cognitive deficits in neurodegenerative diseases has focused so far almost entirely on memory, language, attention, visuospatial perception and executive functioning (Gleichgerrcht et al., 2010).

In the past decade, however, the study of decision-making in these conditions has increased, prompting the development of new tasks that have enabled this cognitive process to be readily assessed. In clinical practice, it is not uncommon to find early persons with behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) who, to a considerable extent, are intellectually unimpaired, while relatives and caregivers depict a strikingly different picture: they claim that these patients show severe changes in their behaviour and real-life decision-making skills (e.g. Rahman et al., 1999; Manes et al., 2011).

The literature has so able to identify the orbitofrontal, anterior cingulate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices as being critical to decision-making (Rosenbloom, Schmahmann and Price, 2012).

A schematic view of the important neural substrates proposed by Rahman and colleagues (Rahman et al., 2001) is shown in Figure 1.

Rahman and colleagues showed that patients with behavioural variant frontemporal dementia exhibited a profile of risk-taking, not impulsive, behaviour in decision-making, suggestive of dysfunction in the ventromedial prefrontal or orbitofrontal cortex. Kloeters and colleagues (Kloeters et al., 2013), fourteen years later, published results showing that atrophy in the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala correlated with performance on the Iowa Gambling Task used in their study to examine decision-making.

A large proportion of human cognitive social neuroscience research has focused on the issue of decision-making thus far.

Impaired decision-making is a symptomatic feature of a number of neurodegenerative diseases, but the nature of these decision-making deficits depends on the particular disease.

Once you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met one person with dementia. Each person with dementia will have a cognitive profile according how far progressed the condition has reached, and the extent to which functional problems are perceived. This might depend on the likely diagnostic category in which a patient living with dementia finds himself or herself.

Examining the qualitative differences in decision-making impairments associated with different neurodegenerative diseases provides potentially valuable information regarding the underlying neural basis of decision-making.

A good account of decision-making in different neurological conditions including dementia is provided by Brand, Labudda and Markowitsch (2006).

Figure 2 shows a schematic view of some of the key processes.

The features of their model are as follows.

General problem solving strategies, also stored in long-term memory, need to be recalled in order to evaluate which strategy seems to be appropriate in order to decide advantageously. The recall of this information, including personal autobiographical experiences and general strategies that have been developed during life, is triggered and controlled by executive components, for example cognitive flexibility.

In working memory, the features of the current decision and the retrieved information from long-term memory are combined to generate or initiate a current decision strategy that guides the decision.

In this process, “somatic markers”, which means biasing signals from the body or mental representations of them, can also guide the selection of an appropriate strategy. The decision itself leads to positive or negative feedback (e.g., gain or loss of a specific amount) that activates an bodily autonomic response.

The feedback – or the somatic markers, which are the results of the emotional feedback – can also result in an alteration of the information stored in long-term memory as well as – in a more direct way – the representation of somatic markers associated with comparable decisions.

The comparison of the profiles of decision making in different conditions, which can cause dementia, are arguably helpful in predicting what the person with dementia might expect. Several studies have reported altered decision-making in Parkinsons’s disease (Perretta et al., 2005) and pathological gambling has been found in Parkinsons’s disease patients with L-Dopa medication (Weintraub et al., 2006) attributing a key role to the chemical dopamine in taking risky decisions.

Recent studies also investigated decision-making in Huntington’s disease and found that learning and memory processes, rather than motivational processes, are responsible for decision-making deficits in this group (Busemeyer and Stout, 2002).

Hampton and O’Flaherty (2007, some years ago, mapped out the neural substrates of reward-related decision making with functional MRI. They identified that the combined signals from three specific brain areas (anterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, and ventral striatum) were found to provide all of the information sufficient to decode subjects’ decisions out of all of the regions studied.

These findings appear to implicate a specific network of regions in encoding information relevant to subsequent behavioral choice. Evidence for the important role of the orbitofrontal cortex and the amygdala in decision-making particularly under ambiguous conditions comes from a recent study by Hsu and colleagues (Hsu et al., 2005)).

Dementia of the Alzheimer type (DAT), the cause of the most cases of dementia worldwide, is typically characterised by typical structural, neurochemical and cognitive changes as the disease progresses.

Pathological changes in mild DAT affect primarily the medial temporal lobes and limbic structures (e.g., entorhinal cortex, hippocampus), and then extend to the association cortices of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes (Braak and Braak, 1991).

Ha and colleagues have argued that the changes in DAT fundamentally alter the frames of reference for making decisions (Ha et al., 2012).

The study by Delazer and colleagues further highlighted important differences in decision-making between mild DAT patients and healthy controls (Delazer et al., 2007). Findings from the study by Sinz and colleagues are consistent with the notion that decisions under ambiguity as well as decisions under risk are impaired in mild DAT (Sinz et al., 2008). It may thus be expected that patients with mild DAT have difficulties in taking decisions in everyday life situations, both in cases of ambiguity (information on probability is missing or conflicting, and the expected utility of the different options is incalculable) and in cases of risk (outcomes can be predicted by well-defined or estimable probabilities).

The legal instrument to assess capacity through the Mental Capacity Act (2005) is very blunt. Characterising an ability of a person living with dementia to make optimal decisions is essential for giving confidence to that person (and those closest to him and her) that such risks are being managed appropriately.

It is likely that the implementation of the Mental Capacity Act will come under increasing scrutiny, in parallel with advances in decision-making research in cognitive neuroscience and cognitive neurology.

References

Braak, H., Braak, E. (1991) Neuropathological staging of Alzheimer-related changes, Acta Neuropathologica (Berl), 82, pp. 239–259.

Brand, M., Labudda, K., Markowitsch, H.J. (2006) Neuropsychological correlates of decision-making in ambiguous and risky situations, Neural Netw, 19(8), pp. 1266-76.

Busemeyer, J. R., Stout, J. C. (2002) A contribution of cognitive decision models to clinical assessment: Decomposing performance on the Bechara gambling task, Psychological Assessment, 14, pp. 253–262.

Delazer, M., Sinz, H., Zamarian, L., Benke, T. (2007) Decision-making with explicit and stable rules in mild Alzheimer’s disease, Neuropsychologia, 45(8), pp. 1632-41.

Gleichgerrcht, E., Ibáñez, A., Roca, M., Torralva, T., Manes, F. (2010) Decision-making cognition in neurodegenerative diseases, Nat Rev Neurol, 6(11), pp. 611-23.

Ha, J., Kim, E.J., Lim, S., Shin, D.W., Kang, Y.J., Bae, S.M., Yoon, H.K., Oh, K.S. (2012) Altered risk-aversion and risk-taking behaviour in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, Psychogeriatrics, 12(3), pp. 151-8.

Hampton, A.N., O’Doherty, J.P. (2007) Decoding the neural substrates of reward-related decision making with functional MRI, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104(4), pp. 1377-82.

Hsu, M., Bhatt, M., Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., Camerer, C. F. (2005) Neural systems responding to degrees of uncertainty in human decision-making, Science, 310, pp. 1680–1683.

Kloeters, S., Bertoux, M., O’Callaghan, C., Hodges, J.R., Hornberger, M. (2013) Money for nothing – Atrophy correlates of gambling decision making in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, Neuroimage Clin, 2, pp. 263-72.

Manes, F., Torralva, T., Ibáñez, A., Roca, M., Bekinschtein, T., Gleichgerrcht, E. (2011) Decision-making in frontotemporal dementia: clinical, theoretical and legal implications, Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 32(1), pp. 11-7.

Rahman, S., Sahakian, B.J., Hodges, J.R., Rogers, R.D., Robbins, T.W. (1999) Specific cognitive deficits in mild frontal variant frontotemporal dementia, Brain, 1999, 122 (Pt 8), pp. 1469-93.

Rosenbloom, M.H., Schmahmann, J.D., Price, B.H. (2012) The functional neuroanatomy of decision making, J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci, 24(3), pp. 266-77.

Sinz, H., Zamarian, L., Benke, T., Wenning, G.K., Delazer, M. (2008) Impact of ambiguity and risk on decision making in mild Alzheimer’s disease, Neuropsychologia, 46(7), pp. 2043-55.

Weintraub, D., Siderowf, A. D., Potenza, M. N., Goveas, J., Morales, K. H., Duda, J. E., Moberg PJ, Stern MB. (2006) Association of dopamine agonist use with impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease, Archives of Neurology, 63, pp. 969–973.

The ‘NHS Five Year Forward Plan’ is a clever marketing stunt, and is barely a statement of strategy

There’s no “magic money tree”, except when you’re signing off HS3 on a ‘nod and a wink’ for £7 billion, or interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan for £30 billion.

As a piece of marketing, for Simon Stevens to set out a stall for the rôle of the NHS in a global economy, “the five year plan” was nice and succinct. As a piece of strategy, it is dreadful. It’s dreadful – even if you decide to take the view that health policy is entirely market-driven or “value-based”, and not in any way written through a sophisticated clinical prism.

The irony of a “five year plan” for the National Health Service is pretty quick to see. “Five year plans” were, of course, used by Stalinist Russia. Nazi Germany preferred ‘four year plans’ as a strategy for war readiness, in comparison.

It is reported that the “Five Year Forward View”, published last week by NHS England, is a collaboration between six leading NHS groups including Monitor, Health Education England, the NHS Trust Development Authority, Public Health England, the Care Quality Commission and NHS England.

And yet ironically the future of two of the contributing organisations is under doubt. In a fringe meeting earlier this at the Labour Party Conference, it was again mooted what the precise function of Monitor might be. This is because it is definite that an incoming Labour Party government, in its first Queen Speech, will repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012), a much loathed piece of legislation. This leaves the precise functions of Monitor uncertain.

One possibility which Burnham is seriously contemplating is whether Monitor, if it continues to exist, serves to regulate the integration of services as would be expected in ‘whole person care’. Burnham intends to introduce ‘NHS preferred provider’, which could insist on the NHS being the lead provider in contracts for as long as ten years in the ‘prime contractor model‘.

And the future of the Care Quality Commission was put on a cliff-edge with the report of the Sir John Oldham Commission, again to do with whole person care. It would make much more sense to reform the regulators to oversee health and care with a single regulator in future. This would again be in line with the regulation of health and care professionals, much needed, and proposed by the English Law Commission, but kicked into the long grass by the current Government as it ran out of time.

The “5 year Forward View” to all intents and purposes reads like a marketing document, a wish-list for further privatisation of the NHS. It may ‘pack a punch‘, from the BBC which has unreservedly succeeded in throttling any discussion of the NHS reforms. But talk of ‘accountable care organisations’, as developed in Spain and the United States, and the emphasis on preventive health packages so keenly sold by multinational corporates, are paradigmatic of a wish-list of a privateer.

The document is a naked shill, intended to carry on the ‘case for change’ which has been made exhaustively by think tanks such as the King’s Fund which, some might say, were instrumental in giving the catastrophic policy of market competition in the National Health Service some legs in the first place.

But the runes are clearly there.

Take, for example, the seemingly-modest proposal of “integrated care commissioning”. The policy of personal budgets in the full glare of sunlight looks incredibly anaemic. Unanswered questions exist how a universal health system is going to be successfully merged with a means-tested care system. NHS England tried, unsuccessfully, to head this issue off at the pass as far back as in 2012.

Personal health budgets, which Simon Stevens has continued to speak moistly of, are the perfect vehicle for introducing ‘top ups’ and ‘copayments’, threatening the fundamental principle of universal, free-at-the-point-of-need.

And moves, not contained in the ‘5 year plan’, spell out an ominous direction of travel. It has just been announced that the much maligned contract for processing ATOS, given under the last Government to ATOS, is to be given to a company called Maximus, which has a proven track record in handing long term care packages in other jurisdictions.

“Independent” think tanks have never shrugged off successfully the “power of the prepaid cards”, see for example the DEMOS initiative. It has always been vehemently denied that there will be no merging of universal credit and healthcare provision, although Liam Byrne’s account of Jennie Macklin in Australia painted a rather different story in an article in the Guardian provocatively entitled “Let’s help disabled people achieve their full potential“.

Like a multi-national corporate document, the “5 year plan” is high on marketing but poor on strategy. A good example of this is given on page 36 in relation to a ‘threat’ facing the National Health Service, that of recurrent pay freezes to the majority of nurses whilst the economy is reputed to be recovering.

The seemingly innocuous line, at the end of page 35, reads: “For example as the economy returns to growth, NHS pay will need to stay broadly in line with private sector wages in order to recruit and retain frontline staff.” But it is well known that any wish to pay nurses a wage that reflects the value that runs through their work like letters in a stick of rock will be strongly resisted by the Treasury, while the Conservative Party will prefer further to tattoo the words of low taxes onto his breast plate of ideology.

There are other clear examples of the document clearly lacking in clarity. For example, page 33 sees a promotion of ‘personalised medicine’, how the NHS and “our partners” (meaning in the third and private sector, actually) might deliver the genome based ‘revolution’. Again, the document’s thrust is one of marketing, not clear strategy. There is no mention of the changes in resource allocation which would be required to serve this revolution, essentially seeing hardworking taxpayers subsidise the shareholder dividends or surpluses of large corporate-like charities. There is absolutely no mention of the changes in the legislative framework that would be needed, as in the United States, to prevent genetic information non-discrimination. But here again the document serves its marketing function – as a prospective prospectus for would-be investors wishing to spot lucrative opportunities in the NHS as a data mine.

Like there is no mention of “NHS preferred provider”, unsurprisingly there is no mention of “whole person care”. And yet, even if Labour fail to win an outright majority, it will seek to implement this being the largest party in Government. And this policy is set to see a profound change in the landscape of health and care provision for England.

In any business strategy, one is obliged to think of the political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental headwinds (affectionately known as “PESTLE” to business strategists). A good example of social changes in the five years might have been, for example, a change in direction of the NHS being seen as resentment as costing much money, despite its striking efficiency, but one which values its workforce (for example in the salary of most of its nurses).

Looking at the political headwinds, it is quite incredible for example there is no mention of trade agreements such as TTIP and the investor-to-state dispute settlement clauses. If this ‘5 year forward plan’ had been at all serious, it would have been included, not least as it is a headwind which could drastically throw off course further the direction of travel of the NHS as a state-run health service.

Simon Stevens’ vision is a ‘charismatic vision’ of sorts. But a vision does not have to be particularly credible for it to get populist appeal or succeed. It just needs to be communicated clearly, with supine and compliant supporters in the trade media.

If the document were a ‘heads up’ for how we could afford a NHS through general taxation which was genuinely universal and free at the point of need, this document would have served a function. As it is, the document is a lubricator for mechanisms which could optimise the part that the private sector has to play, with no mention of the dogs being unleashed in the global marketplace – in much the same way Cameron refused to signpost “the top down reorganisation”. It is impossible for a strategy document for the NHS simply to airbrush out the political and legal factors which will be at play in the lifetime of the next Government. As it is, the NHS ‘5-year forward view’ is a basic piece of marketing, which as a strategic plan scores 0/10.

Stigma in dementia poses crucial questions for dementia friendly communities

The literature on stigma is comprehensive.

But Kate Swaffer added to it beautifully in the journal ‘Dementia’, with an article today – on open access – entitled “Dementia: Stigma, language and dementia friendly”.

Kate refers to a blogpost by Ken Clasper, a Dementia Friends Champion, which asks, sensibly, what we are trying to achieve with more ‘awareness’.

And if you scroll down to the end of this tour de force on stigma and dementia, you’ll see exactly why Kate is able to opine with such legitimacy and authority.

I conceded a long time ago – in March 2014, in fact – on this blog that the policy plank of ‘dementia friendly communities’ is an incredibly complex one.

The discussion of stigma seems to be one of perpetuity. We’ve seen numerous attempts at it, including the original work of Goffman (1963) on stigma and ‘spoiled identity’.

It’s been re-incarnated as a Royal College of Psychiatrists campaign on stigma.

This morning there was another bite of the cherry.

The report, New perspectives and approaches to understanding dementia and stigma, published by the think tank International Longevity Centre UK (ILC-UK) is produced by the MRC, Alzheimer’s Research UK, and Alzheimer’s Society; it was also supported by Pfizer.

I’ve thought how I could possibly respond to Kate. And I can’t, as Kate is in every sense of the word an ‘expert’.

But it did get me thinking.

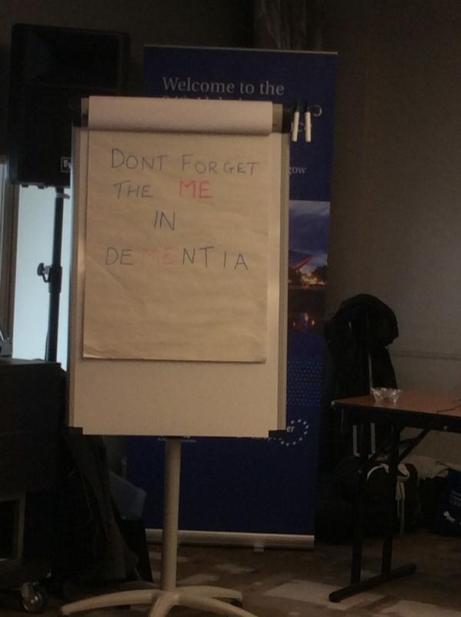

It got me thinking of the happy times I had with Chris and Jayne last week at the Alzheimer Europe conference in the city of my birth in Glasgow.

‘There’s more to the person than the diagnosis” is one of the key five messages of ‘Dementia Friends’, an initiative from the Alzheimer’s Society predominantly (and Public Health England). This is mirrored in a tweet by Chris from this morning.

Chris is also a “Dementia Friends Champion“, and lives well with dementia.

Last week, I attended a brilliant all-day workshop chaired by Karishma Chandaria, Dementia Friendly Communities manager for the Alzheimer’s Society. The progress which has been made on this policy plank is substantial, and I am certain that the next Government will wish to support this policy initiative in the English for 2015-20.

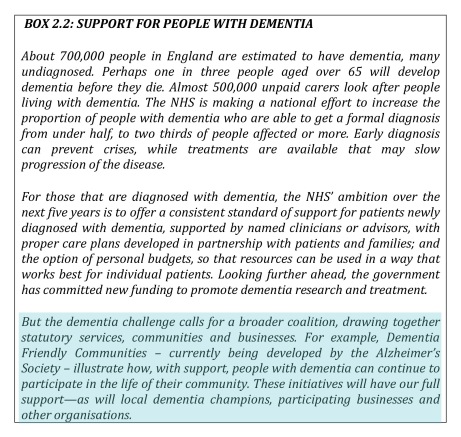

It is stated clearly in Simon Stevens’ “Five Year Plan” for NHS England.

It is a core thread of the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge.

And the ‘coalition of the good’ has seen the dementia friendly communities policy plank develop drawing on work from ‘Innovations in dementia’ and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

And to give the Alzheimer’s Society credit, where it is certainly due, there has been launched an open consultation for a British Code of Practice (currently ongoing), to which anybody can contribute.

But this code of practice does, again, have the potential to be very divisive. It might be painful to make dementia friendly communities, such as the large one in Torbay, ‘fit into this box’.

Torbay in many ways is a beacon of innovation for integration between NHS and care. There is genuine “community bind”, with citizens, shopkeepers, transport, police, for example, contributing.

The article on the BBC website about Norman McNamara (January 2012) predates the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge, (which started in March 2012.)

Any top down way of making bottom-up social groups ‘conform’ will be hugely problematic in the implementation of this approach to dementia-friendly communities, potentially.

The methodology of dementia friendly communities has to be truly inclusive: it is all or nothing.

I agree with Kate, and like her I wish to avoid protracted circular definitions of ‘stigma’. For me, I recognise stigma when you see it, like how the Supreme Court of the US recognises erotica and pornography as per Jacobellis v Ohio [1964].

It is possibly easier to define stigma by its sequelae, such as avoiding wishing to talk about dementia in polite conversation, or not wishing to see your GP about possible symptoms of a dementia in its early stages, or not wanting to socialise with people with dementia who happen to be in your family.

We know these are real phenomena, as demonstrated, for example, by the loneliness of many people on receiving a diagnosis of possible dementia.

And we know stigma can harbour deep-seated irrational prejudice, like the incorrect notion that dementia is somehow contagious like a ‘superbug’.

Stigma can be exhibited in pretty nasty ways in language: such as “snap out of it” or “victim”.

My discussion of whether people living with dementia are ‘sufferers’ tends to go round and round in circles with people who disagree with me.

Suffice to say, I agree it is possible for a person living with dementia, such as a person who has received a diagnosis of Lewy body dementia and who has to put up with terrible “night terrors” and exhaustion the following day.

I think if you live independently, but with full insight into your symptoms, it can be exasperating. I have never been in that position though, and it would be invidious of me to second-guess.

I think if you are close to someone in the latter stages of dementia, you can suffer.

But I’ve written about this all, indeed on this blog, before here.

The only thing that is new is Peanuts’ cartoon (original citation here).

In that workshop, I also sat through Joy and Tone Watson’s brilliant “Dementia Friends” session. Joy lives with dementia. And their session was brilliant.

This was the final ‘exhibit’.

I attended a special group session on stigma with Toby Williamson from the Mental Health Foundation during that day. In that session, it was mentioned that ‘rôle models’ of people living well with dementia might help to break down stigma.

Or maybe guidance for the media might help? One cannot help wondering if an article such as in the Daily Mail today might actually put off people from seeking a diagnosis of dementia (completely unintentionally).

But I did bring up something on my mind.

“Stigmata” literally means signs.

But dementia can be, like other disabilities, quite invisible.

Somebody might have insidious change in personality and behaviour, noticed by somebody closest to him or her, with no obvious changes in cognition (nor indeed in investigations).

I showed this in my paper published in Brain in 1999, currently also in the Oxford Textbook of Medicine.

The condition I refer to is in fact one of the more prevalent causes of dementia in the younger age group, called the “behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia“.

If the signs are ‘visible’, then you are obliged legally to make reasonable adjustments for any disability. In England, this includes dementia under the guidance to the Equality Act (2010).

As Toby Williamson says, if you’re obliged to build a ramp for somebody in a wheelchair for a place of work, there’s an equal obligation to produce adequate signage for people who have navigation problems as a result of a dementia such as dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.

There are reams and reams of evidence on equality and the built environment (for example the Design Council or Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment).

I personally think it’s brilliant you can go into certain shops, and the customer-facing staff will, potentially, be able to recognise if a person does need time and space to pay for items.

This is also been tackled in the Scottish jurisdiction through Alzheimer Scotland.

Also, corporate lawyers should be advising large employers about the scope for unfair dismissal claims by people dismissed as they are about to arrive at a diagnosis of dementia (particularly young onset dementia).

The timeline is roughly this. Somebody has health problems – he or she is invited to leave and given a pay off – these health problems turn out to be a diagnosis of probable dementia – by this time the dismissal is not unfair.

I feel confident the ‘dementia friendly communities’ policy strand in England, and across other jurisdictions, is here to stay. I share, though, Kate’s concerns that about the relative ease with which this policy has lifted off, say, compared to how one might feel about ‘gay friendly communities’ or ‘black friendly communities’. One has to be extremely careful about any policy plank which alerts people to divisions, “them against us”.

This is what I know best as the “don’t think of elephants phenomenon” and then you think of elephants.

This policy, anyway, currently has huge momentum. Marc Wortmann is currently Executive Director of Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), the organisation providing a global voice for dementia and the founder of World Alzheimer’s Month. Wortmann has been instrumental in propelling dementia friendly communities to the foreground of world policy.

But, in firing up ‘dementia friendly communities’ (a term which I think is sub-optimal’), v 2.0, there is plenty of time to get it right.

Specialist nurses should form part of the post-diagnostic care and support network for living well with dementia

Background: There have been numerous concerns that the health and care system in England is too fragmented, and lacks sufficient focus for a person with dementia or caregiver to navigate through the system.

A complex array of health and social care services is needed to support people living with dementia; “carers find navigating systemic issues in dementia care time-consuming, unpredictable and often more difficult than the caring work they undertake.”(Peel and Harding, 2014).

One of the “pillars” of the Scottish strategy invokes a “dementia practice coordinator“.

This rôle is: “a named, skilled practitioner who will lead the care, treatment and support for the person and their carer on an ongoing basis, coordinating access to all the pillars of support and ensuring effective intervention across health and social care”.

There are a number of possible professions which might be involved in this care coordinating role: for example, GPs taking a proactive approach to their patients, or social care practitioners who might have particular expertise in safeguarding issues (e.g. Manthorpe et al., 2007).

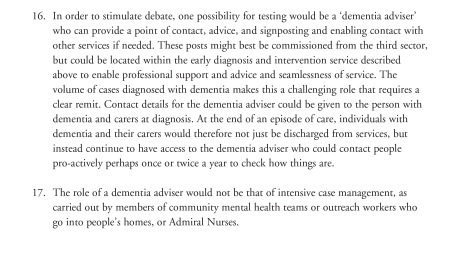

The Alzheimer’s Society suggest a “dementia adviser” role.

In this framework, the dementia adviser service would be ‘primarily for people with dementia, as well as their supporters and carers. It provides them with a named contact throughout their journey with dementia. Referrals to the service may come from GPs, CMHTs or other health and social care professionals, or self-referral.’

It is interesting to note that such a rôle was described clearly in the 2009 Department of Health English strategy document for dementia policy: “Living well with dementia”:

Clinical nurse specialists (CNS) in cancer perform a range of complex activities, including the management of care.

Recent evidence from the University of Southampton suggests that a properly trained and educated dementia specialist nurse, undertaking a clearly defined role, and working directly with people with dementia and their carers for a significant proportion of the time, could benefit people with dementia in hospitals. If these benefits addressed only a fraction of the excess stays experienced by people with dementia, a significant return on investment could be obtained.

CNS who practise proactive case management and refocus services in line with best practice represent a good return on investment (Leary and Baxter, 2014).

Recently, calls have been made to expand a pioneering dementia pilot in Norfolk after an almost £110,000 investment resulted in more than £400,000 savings for health and social services in less than a year.

The meaning of the term ‘timely diagnosis’ in dementia has recently come under close scrutiny.

For example, Dhedhi, Swinglehurst and Russell (2014) state that: “Reluctance or failure to make a diagnosis on a particular occasion does not necessarily point to GPs’ lack of awareness of current policies, or to a set of training needs, but commonly reflects this range of nuanced balancing judgements, often negotiated with patients and their families with detailed attention to a particular context.”

The Carers Trust has been working with the Royal College of Nursing to adapt the Triangle of Care to meet the needs of carers of people with dementia when that person is admitted to a general hospital. This approach, which has gathered some momentum in English policy, puts the person living with dementia in a ‘triangle of care’ in a ‘triangle of care’ with professional and carer (see page 6).

There is clearly a potential rôle for a third sector charity, such as Dementia UK, in providing clinical nursing specialist input. The success of Macmillan Cancer in the ‘prime contractor’ model for integrating cancer and end-of-life care in Staffordshire, as an example of outcomes-based commissioning, is, arguably, a very good recent paradigmatic example.

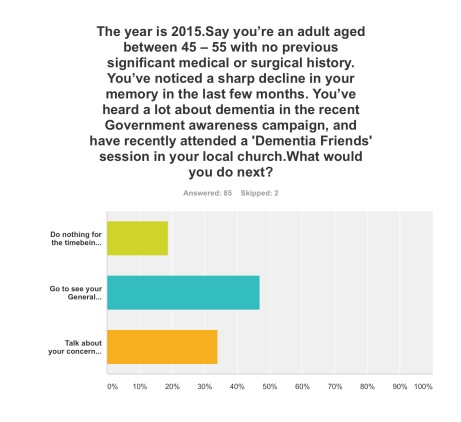

Aim: To conduct a preliminary online survey into citizens’ attitudes to what post-diagnostic support in the English jurisdiction could look like.

Methods: 87 respondents completed the online “Surveymonkey” survey, invited from a Twitter account with around 12000 followers. The survey could only be completed once.

You were invited to be a person who had just received a diagnosis of dementia in the English jurisdiction.

Exclusions: None.

Results:

Q1. By far, the most preferred option was to go to see your General Practitioner with a view to receiving, if correct, a diagnosis of early dementia, if you’d noticed a decline in your memory and been aware of a public campaign on dementia (47%); talking about your concerns with your friends or family, to see what they suggest, was the next preferred option (34%).

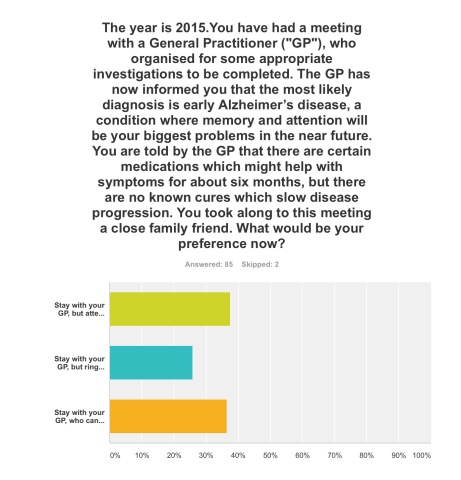

Q2. This was extremely finally balanced. One option was most preferred (38%), that of staying with your GP, but attending for the next couple of years regular six-monthly meetings with a hospital neurologist to observe follow-up with CPN support; but only just, as staying with your GP, who can help organise care and support for you and your closest consisting of a multidisciplinary team, was the next preferred option (36%). The option to stay with your GP, but ring up a local charity helpline to see what they can suggest to help you, regarding information and life choices, was the least preferred (26%).

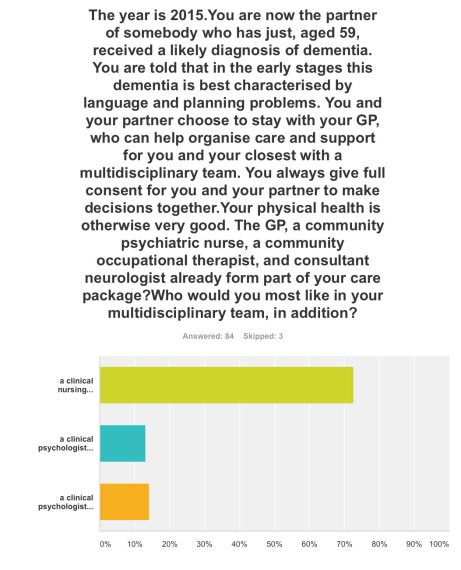

Q3. The option where a clinical nursing specialist had been added incrementally to a speech and language therapist and clinical psychologist was by far the most popular option (72%).

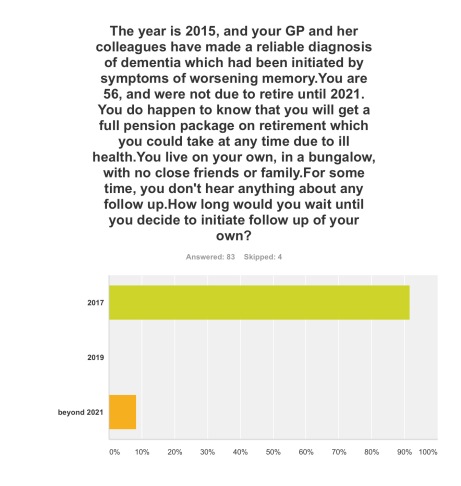

Q4. The option where you initiated follow-up for post-diagnosic support following diagnosis as soon as possible, relatively in 2017, was by far the most popular option (92%).

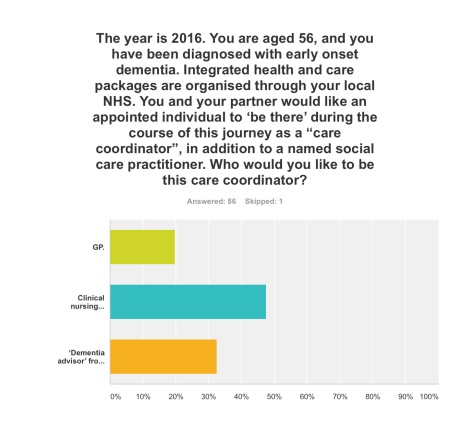

Q5. Three options were given for who the ‘care coordinator’ could be. A clinical nursing specialist was by far the most preferred option (48%), then ‘dementia adviser’ from a well known charity (33%), and then the GP last (19%).

The rôle of the ‘dementia adviser’, particularly at the earlier stages of the condition at least, is clearly worth considering in future policy such as the English dementia strategy 2015-20.

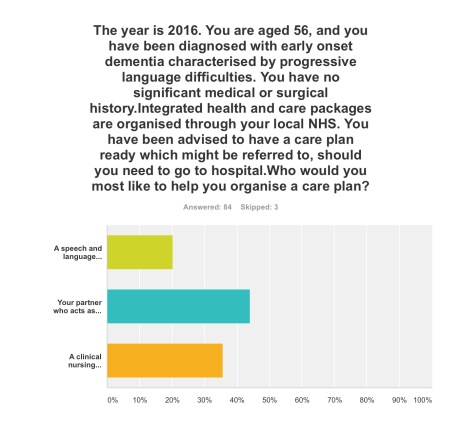

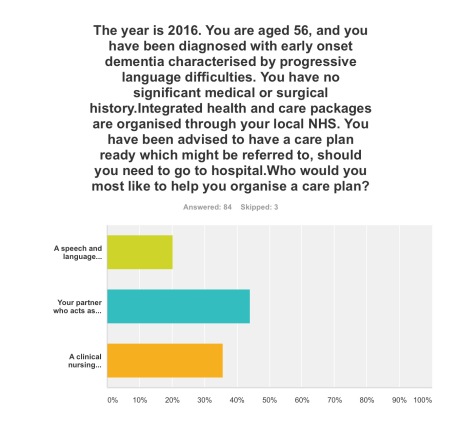

Q6. This question asked who you would like the most to organise your care plan with you: your primary caregiver was the most popular choice (44%), with a clinical nursing specialist the next popular choice (36%).

Q7. Here it was introduced that a clinical nursing specialist was one of the options in the new English dementia strategy (2015-20). The rationale for this, most felt, should come from clinical outcomes (76%), then financial considerations from the funding situation of the NHS and care (14%). The option where powerful lobbying from charities (“third sector”) should be the driver for specialist nurses was the least preferred (10%).

Discussion: The results confirm previous anecdotal reports of the need for timely post-diagnostic support following ‘timely diagnosis’. They paint a picture of a person who has become aware of dementia awareness campaigns and noticed possible symptoms in himself wishing to trust to see a General Practitioner to receive a diagnosis. On receipt of that ‘timely diagnosis’, he or she would be keen to initiate post-diagnostic support as soon as possible, with a multidisciplinary team; it is striking that a clinical nursing specialist was preferred to the rôle of the ‘dementia adviser’ from a charity previously mooted; and that the decision in policy to implement clinical nursing specialists should be made on the basis of clinical outcome, not financial pressures in which the NHS and care find themselves. Notwithstanding that, the results support heavily a ‘triangle of care’ involving a caregiver and a professional, such as a person living with dementia, in the formation of a personalised care plan.

Limitations: There are no geographical data of the locations, or other demographic data, of the respondents to this online survey. Responses might be biased by the nature of the Twitter threads which had invited respondents to participate, or the nature of the followers of those threads. The questions assume a working knowledge of what the key personnel in a multidisciplinary team for dementia care and support do.

Although respondents were advised to select one of the options, however inadequate the options were, it is a limitation of this study that options did not include social care practitioners. Social care practitioners will, however, have a critical rôle in dementia post-diagnostic care and support.

Conclusions: The findings taken together provide important considerations for future policy-makers regarding post-diagnostic support for dementia in the English jurisdiction, urging the need for a rôle for clinical nursing specialists in delivering prompt post-diagnostic support and in avoiding, on the basis of clinical need, inappropriate care in hospitals.

Selected readings

Carers Trust/Royal College of Nursing. (2013) The triangle of care. Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice for Dementia Care

Dhedhi SA, Swinglehurst D, Russell J. (2014) ‘Timely’ diagnosis of dementia: what does it mean? A narrative analysis of GPs’ accounts, BMJ Open, Mar 4, 4(3):e004439.

Leary A, Baxter J. (2014) Impact of lung cancer clinical nurse specialists on emergency admissions, Br J Nurs, Sep 25, 23(17), pp. 935-8.

Manthorpe J, Clough R, Cornes M, Bright L, Moriarty J, Iliffe S; OPRSI (Older People Researching Social Issues). (2007) Four years on: the impact of the National Service Framework for Older People on the experiences, expectations and views of older people, Age Ageing, Sep, 36(5), pp. 501-7.

Peel E, Harding R. (2014) ‘It’s a huge maze, the system, it’s a terrible maze': dementia carers’ constructions of navigating health and social care services. Dementia (London), Sep, 13(5), pp. 642-61. d

The 24th Annual Conference for Alzheimer Europe put people with dementia in the driving seat. Deservedly so.

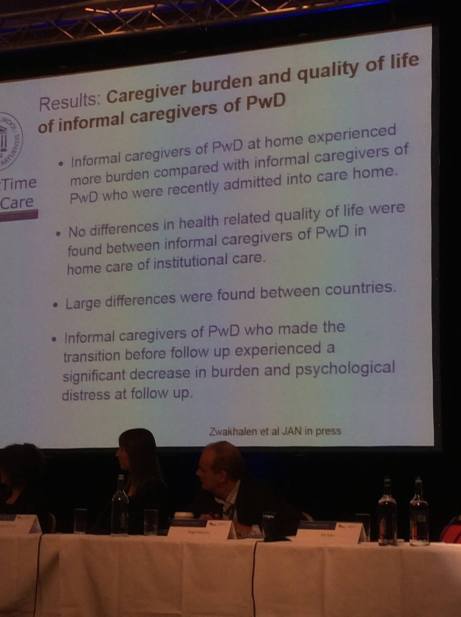

The biggest dementia conference to be taken place in Scotland (“Conference”, attended by 800 professionals, people with dementia and carers) was held in Glasgow last week (20-23 October 2014).

The focus of the conference was Dignity and autonomy in Dementia and the four day event explored in quite some detail how recognising the human rights of people with dementia, their carers, partners and families is key to ensuring dignity and respect, as well as overcoming stigma.

It was the 24th Annual Conference of Alzheimer Europe (@AlzheimerEurope, an umbrella organisation of 36 Alzheimer associations from 31 countries across Europe), supported this year by Alzheimer Scotland, .

The timetable was exacting.

The people there were very special; for example Tommy Whitelaw (@TommyNTour) mentioned in Alex Neil MSP’s speech at the conference. Tommy and Irene Oldfather (@IreneOldfather) happened to be passing through during one of my poster sessions.

And Beth Britton (@BethyB1886).

Well done to the conference organisers for putting it together, especially Gladwys Guillory.

The main conference hall of the venue, the Crowne Plaza in Glasgow, the Argyll Suite, was majestic.

I particularly liked the ‘live Twitter feed’ at the front of the hall, where curiously Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer) appeared many times all the way from Australia. Here I am appearing with my ‘selfie’, with somebody well known in the foreground of the photograph.

The relative failure of the medical model in addressing the needs of people with dementia and caregivers was a pervasive theme throughout the whole conference.

I had a nice chat with Marc Wortmann (@marcwort) over one of the lunches. Marc is in charge of all aspects of ADI’s work (ADI = Alzheimer Disease (and associated conditions) International; @AlzDisInt). Collaborating with the Board, Marc implements finance and campaign strategies.

Marc represents ADI at international conferences and in the NCD Alliance and takes part in WHO and UN meetings. I was also able to bump into Jean Georges (@JeanGeorgesAE), the Executive Director of Alzheimer Europe.

Cabinet Secretary for Health, Alex Neil, delivered a clear keynote speech to the conference at the Tuesday morning plenary session, in which he paid tribute to the immense contribution of Tommy Whitelaw.

Key to the event was the signing of the Glasgow Declaration: a commitment to promoting the rights, dignity and autonomy of people living with dementia across Europe, as guaranteed in the European Convention of Human Rights and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Here’s a great slide of @alzscot‘s “PANEL” (pic taken by @LauraMcC86).

The satellite symposium sessions were well put together, and attracted substantial audiences.

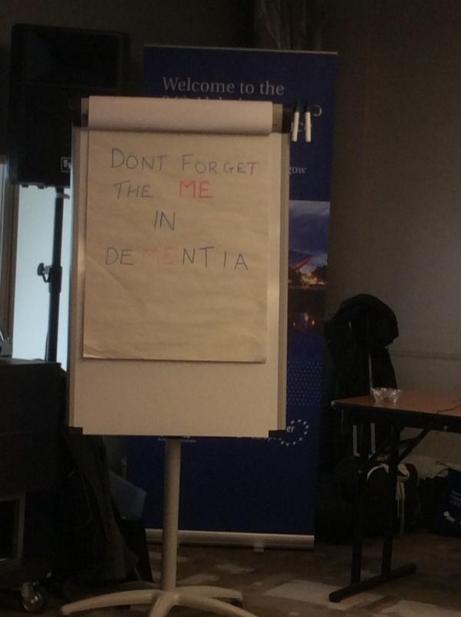

There was an amazing moment when Agnes Houston (@Agnes_Houston), Chair Scottish Dementia Working Group, said to Helga Rohra (@ContactHelga), the Chair of the satellite session and Chair of European Persons With Dementia, “All we people with dementia need is a bit of help — AND A BIT OF TIME!”

A quotation from Agnes – from a previous conference – says it all for me.

The audience burst out laughing.

The reason for this is that Agnes had been originally timetabled to have more time for her slot, apparently.

As the conference was themed around the law, including human rights, invariably discrimination against people with dementia came up in various forms.

I asked about the topic several times.

One talk of the entire programme which I thought was truly outstanding was PL1.3. Gráinne McGettrick (Alzheimer’s Society of Ireland): The UN Disability Convention as an instrument for people with dementia and their carers.

In the English jurisdiction, dementia can count as a disability; therefore there are statutory requirements for ensuring dementia-friendly communities from employers. Also, unfair dismissal of a person on account of being newly diagnosed with dementia will clearly be unlawful.

A member of the audience politely pointed out to me afterwards that a person normally gets sacked first, and then gets his or her diagnosis of dementia confirmed much later, so at the point of dismissal the dismissal does not obviously appear unfair legally.

I found this observation incredibly insightful, as there have been thus far no ‘test cases’ of unfair dismissal on grounds of a diagnosis of dementia in the English jurisdiction.

I had brought along my book ‘Living well with dementia’, but I rarely got a chance to read (or refer) to it during the course of the whole week!

I asked several times why there is no representative of persons living with dementia or caregivers on the World Dementia Council (@WorldDementia). The background to this fiasco is explained here.

I had designed that I would be staying in the same competitively-priced hôtel as Jayne Goodrick (@JayneGoodrick) and Chris Roberts in Glasgow for the 24th Alzheimer Europe conference held in Glasgow, the city where I was born.

It was by chance we gave a lift to Dr Ruth Bartlett (@RuthLBartlett) to the conference venue. Ruth was staying, as it turns out, in the same competitively-priced hôtel.

Ruth is of course well known for her well respected contributions about the citizenship of of people living with dementia, and how this has influenced the ‘involvement’ of people with dementia in policy.

This was us just before the opening ceremony – when we were full of energy.

I really enjoyed speaking with Geoff Huggins (@GeoffHuggins), who gave an excellent speech in the opening ceremony.

I presented my talk on how dementia healthcare would not be best served by a private insurance system, because of the potential problems of ‘moral hazard’ and genetic discrimination.

This talk was, overall, well received.

I was particularly pleased with the wide-ranging, excellent discussion we had after my talk. Thanks especially to Amy Dalyrymple (@Amy_Dalyrymple), Head of Policy for Alzheimer Scotland, whose contributions in all areas of policy were particularly interesting. The work currently being implemented in Scotland represents a culmination of very high quality inclusive work through a number of different stakeholders.

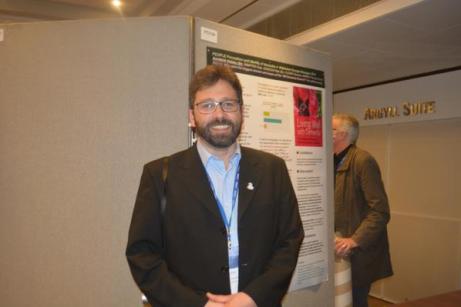

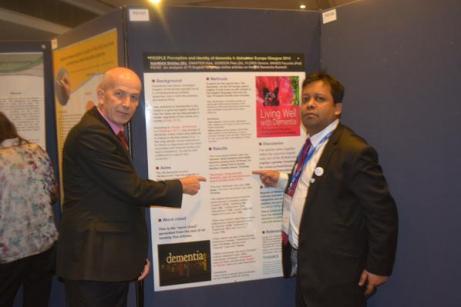

I was also honoured to present two further research posters, which I had co-authored on the perception and identity of the G8 conference.

And here’s co-author Dr Peter Gordon (@PeterDLROW) proudly in front of our poster too!

Chris Roberts (@mason4233) helped me with the poster session. It was in fact Chris who identified that the phrase “living well with dementia” was not used even once in the top 75 web articles on #G8dementia on Google, in about 44000 words odd.

All around the conference were people whose work is directly relevant to my book: for example Silke Kammer – on the arts and music – and Emma Killick (@RealEmmaKillick) who at the excellent MacIntyre leads on children and adults with learning disabilities and/or autism, but is clearly passionate about people with learning disabilities who later have further unaddressed needs on receiving a diagnosis of dementia.

It was terrific to bump into followers everywhere I went. It was great to meet Julie Christie (@juliechristie1) for the first time, whose work on resilience I am much interested in. It was also lovely to see Anna Tatton (@annatatton1) doing so well.

I am well aware of why the Scottish dementia nursing strategy, some say, has become the ‘envy of the world’. It was a huge privilege to meet in person Janice McAlister (@JaniceMcAlister), who was BJN Nurse of the Year Elderly Care 2013. In addition, I found the presentation by Hugh Masters (@HughCMasters), Associate Chief Nursing Officer for the Scottish Government, interesting for insights as to how England might improve its service too.

I happened to meet in the foyer of the Crowne Plaza on Monday night Ann Pascoe, @A_Carers_Voice, somebody who I have not only liked a lot on Twitter, but whose work on rural ‘dementia-friendly communities’ I have massively respected for some time.

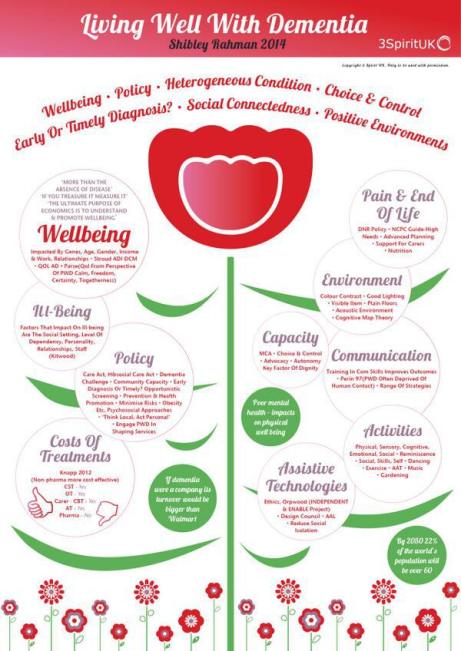

Likewise, it was really nice to catch up with Caroline Bartle (@3SpiritUKNZ), who very kindly once did an infographic of my book ‘Living well with dementia’.

I met in the poster session Prof Mary Marshall to whom the Stirling School in design in dementia owes a huge amount. I owe a huge amount to Prof Marshall too, as the Notting Hill masterclass which I once attended got me first interested in this subject a few years ago (I had a long chat with Prof Marshall there.)

There were not idle tokenistic sops to people living with dementia, and their closest ones, in the whole conference. They were at all times integral to the fabric of the conference.

For example, the seating arrangements in the main Argyll conference suite reflected the special respect given to people with dementia and those closest to them.

The substance of the conference for the most part was of an exceptionally high standard in policy; there was next to no shilling of commercial projects.

The work from Alzheimer Scotland (@alzscot), including, predictably, the work focused on autonomy and dignity, and human rights, was showcased in an impressive way. Their work hangs together as a coherent, forceful narrative of meaningful significance for the Scottish jurisdiction.

It also has clear implications for how England conducts itself south of the border, notably, for example, in a right to timely diagnosis, and a right to timely care and support (including proper coordination of care and support).

In common with Scotland, England is trying to tackle hard the inappropriate use of antipsychotics. Dr Karim Saad (@KarimS3D) gave an excellent talk on this subject, drawing on recent findings from the ALCOVE2 study.

Scotland, in fairness, seems to be having less trouble with its policy than England is.

There was a very good sprinkling of cutting-edge research relevant to all practitioners in the field.

For me, the conference had the feeling of a happy wedding without any of the arguments.

Here are Agnes and Donna.

Whilst originally ‘unkeen’, I ended up having a wonderful time at the “Gala Dinner”. The entertainment – traditional Scottish music and dance – was amazing.

I was able to chat with Agnes and Nancy for some time. What a joy.

Elaine Hunter (@ElaineAHPmh) gave an excellent presentation on the transformative changes which had happened around the workforce in Scotland, including leadership from allied health professionals.

Without doubt, a skilled workforce for the provision of dementia services is essential, not gimmicks.

I consider Helga to be a true friend too. Meeting Helga was akin to being wowed by Lady Gaga.

I had last felt like this when I met Norman McNamara (@norrms) at the Queen Elizabeth II centre in London, Westminster.

I learnt a lot from the all-day workshop on building dementia friendly communities.

Over lunchtime, Joy Watson gave a brilliant ‘Dementia Friends’ (@DementiaFriends) session. I, in fact, was total awe as I am also a ‘Dementia Friends Champion’, and discovered many tips how to run my sessions in future!

This is a brilliant film exhibiting the passion which Joy puts into her Dementia Friends sessions.

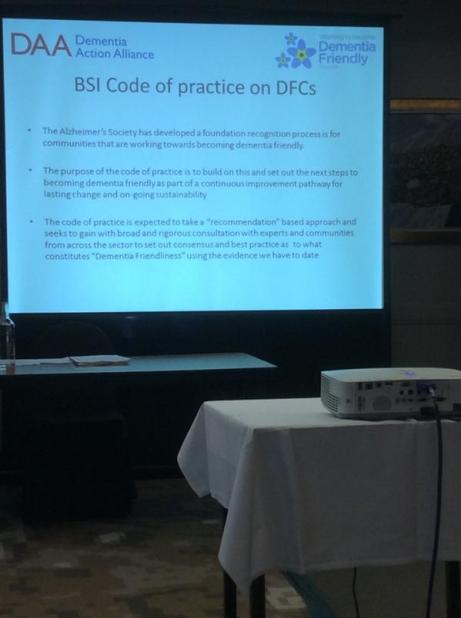

Karishma Chandaria (@Karishma1000) chaired this exceptional day’s workshop, called a ‘masterclass’ on dementia friendly communities, which indeed mentioned the code of best practice for dementia friendly communities currently under consultation.

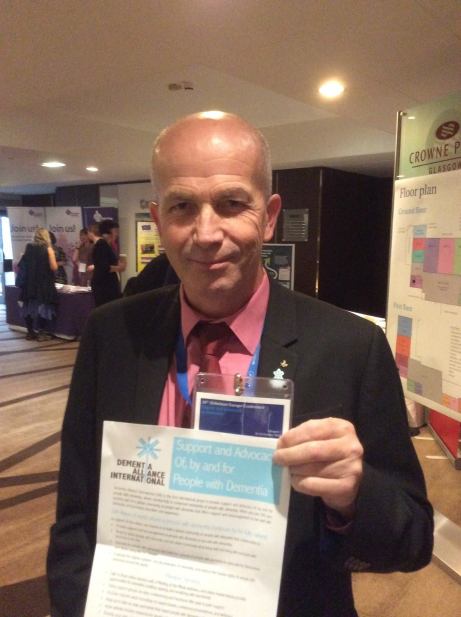

Chris Roberts made time to hand out flyers for membership of the ‘Dementia Alliance International‘, an unique campaigning group run wholly by people living with dementia.

This Conference mapped topics clearly onto people living with dementia and caregivers, for which the organisers of this event must be heavily congratulated.

Next year’s Conference will be in Slovenia. I’ll be there! Bring it on!

What happens after a diagnosis of dementia? My quick survey.

There’s been a lot of diagnosis on improving the diagnosis rates for dementia in primary care as a result of the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge.

This survey which you can take only once asks seven quick questions.

Each scenario is separate.

Choose the best option out of the choices given.

You can only choose one answer. There is no “correct” answer.

The questionnaire does not abruptly end. You need to scroll down to see beyond question 1.

Create your free online surveys with SurveyMonkey , the world’s leading questionnaire tool.

Transforming dementia care is long overdue. Specialist clinical nurses in dementia are now vital.

In the G8dementia, particularly by large corporate-like charities, dementia has been compared to the cancers. Whilst there are many problems with this comparison medically, the aim is for research and service expectations to be met in dementia on an equal footing to those for cancer. There are different types of dementia and different types of cancer, and there is, according to NICE, no current treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, the most common type of dementia globally, which slows the progression of disease. The aim however is undeniably a laudable one. In terms of service provision, the hope is that medical conditions can be detected early (and not at the last minute), and over time care and support can be introduced and implemented in a non-panicky way. The low hanging fruit is for providers at the front end of the service to game the NHS QOF/CQUIN system to design ‘innovative’ packages which might diagnose certain forms of dementia, such as the profound short term learning and memory problems in early Alzheimer’s disease. But getting out of this ‘quick fix’ mentality is going to be essential for the long-term sustainability of dementia services in England I feel. I believe strongly that clinical nursing specialists would not just be a big help here: they are indeed vital. England will really benefit from senior people in dementia taking the bull by the horns, in keeping with a refreshing approach to the long term conditions (LTCs) in general, as helpfully described by the King’s Fund in this policy pamphlet from 2010.

But I have now spoken to two very senior specialist clinical nurses in the NHS. One who has been at the heart of policy for nursing in the last few years, and the other one who has been at the heart of one of the top clinical firms in cognitive disorders here in London for a few decades. They both said exactly the same thing to me: “What we’re fed up about is the fast turnover of services and personnel within them. It’s difficult to find the same person twice. And we’ve got too many people signposting services, and not enough people providing frontline care.” There is undoubtedly a rôle for a trained person who can help to navigate a person with dementia and his or her caregivers around a profoundly complicated system. I’ve heard that “dementia advisers” can be brilliant at a local level, but can easily come to the limits of the skills they can sometimes offer. The system is too bitty and disorganised at the moment; and persons with dementia (some of whom who become ‘experts by experience) and caregivers have a key rôle in optimising design of service and revision provision for dementia in the future.

As a person progresses along “a dementia journey”, a term itself which attracts some considerable criticism, his or her own needs will tend to change from living well independently with dementia to benefiting from increasing levels of support, and then increasing levels of care. Two big events could happen along this ‘journey': the loss of decision-making ability (mental capacity), and the preference to move into a residential home of sorts. The timing of these events can be very hard for people with dementia or their caregivers to predict. There can also be worsening problems in communication between people with dementia and those closest to them, including friends and family. If a person living with dementia needs suddenly to enter hospital as a ‘crisis’ at 4 in the morning, he or she might be blue-lighted in with an infected full bladder causing a deterioration in cognition and behaviour, without a care plan in sight.

Diagnosing dementia is clearly not enough, but a timely diagnosis can be helpful. Professional physicians, nurses and other staff will always consider their professional including moral obligations in how likely the diagnosis is, how much a person wants the diagnosis, and how much to investigate a possible diagnosis. And there are too many cases of the possible diagnosis being given in a busy clinic, often summarised as an ‘information pack'; at worst, some people lost to the system for years before anything new happens.

It is likely that England will develop ‘integrated care organisations’. This does not involve building new departments and new buildings, but is a shift in organisational mindset such that GPs with a specialist skill in dementia service provision can work alongside other trained professionals and caregivers, with the person with dementia. This ‘working together’ is nothing new. It has been brilliantly described in the policy work of the Carers’ Trust in their recent documents ‘A triangle of care’ and ‘A road less rocky’. Caregiving can be intensely rewarding, but can also be hard work with caregivers having specific needs of their own. Caregivers will also be at the very heart of any personalised care plans. A professional who might be involved is a speech and language therapist. There is a national shortage of experienced speech and language therapists which is a tragedy as some forms of dementia, for example logopenic primary progressive aphasia, might be characterised by substantial problems in language in the relative absence of problems in domains such as episodic memory.

As a dementia progresses, a clinical psychologist will be in a brilliant position to work out why a person might have practical problems in real life due to identifiable problems in thinking, such as planning. A planning problem might be manifest as a person being able to make a cup of tea, or to organise a planning trip. Or, a clinical psychologist will be able to tell a team that what appeared to be an optician-related matter with eyesight is in fact a higher order perceptual problem as found in the rarer posterior cortical atrophy type of dementia (where memory can be normal early on.) An occupational therapist can use his or her own expertise here. Whichever way you look at it, dementia service provision needs are likely to be met from clinical teams who are an integral part of the ‘dementia friendly community’, who have been somewhat disenfranchised out of the conversation so far compared to high-street customer-facing corporates. Professionals, even in the context of meeting their regulatory obligations, have, I feel, a massive rôle to play in providing personal communities even if they do not assume legal duty of care. It is now known that activities can not only enhance wellbeing, but can also possibly slow the rate of progression (although the evidence base for this finding is not particularly robust yet.)

In the last few years, since the Health and Social Care Act (2012), was introduced, there has been massive turmoil in the National Health Service (NHS), leading at worst to fragmented services resulting from slick pitches from well funded private providers unable to deliver on their contracts. And yet if the NHS were given the correct management and leadership skills, they could be at the heart of providing world class care in dementia. Economies of scale, with free knowledge transfer, can be advantages of large organisations. Given that there are a million people in the next few years living with dementia, the NHS should be planning ahead for this, not just counting the number of new diagnoses as a manifestation of glorified bean-counting. The drive to diagnosis has been a classic example of where the target has become the means to an end in itself.

Earlier this year in July 2014, it was reported that cancer care in the NHS could be privatised for the first time in the health service’s biggest ever outsourcing of services worth over £1.2bn. The four CCGs were involved, which care for 767,000 patients, are also seeking bidders for a separate £535m contract to provide end-of-life care. Whoever wins the cancer contract will then have to “transform the provision of cancer care in Staffordshire and Stoke”. The prime provider will “manage all the services along existing cancer care pathways” for the first two years after which “the provider will assume responsibility for the provision of cancer care, in expectation of streamlining the service model”, according to details posted by the CCGs on the main NHS procurement website.

Macmillan Cancer Support were able to bring clinical nursing specialists (CNS) to the table: the “Macmillan nurses”. This robust model, which had proper financial backing, has proven to work extremely well in the cancer setting (some details are here). A massive contribution of the CNS is widely thought has been thought to be the “proctive case management”, and not only is this is sound clinical sense but could in the long run save the NHS millions, averting emergency hospital admissions which have been pre-empted. The case for proactive case management has also been established in other neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis. CNS have been described well for the community, but also have a rôle to play in hospitals. Indeed, continuity of care between the community and hospital will be vital, not least because people living with dementia can find unfamiliar people and physical environments extremely distressing. Warrington has seen the introduction of designs which put people living with dementia at ease and the valuing of specialist trained staff. The service provision there is a beacon of success, and shows what can be done if the NHS has a vision and motivation to succeed in this.

CNS could have been a pivotal component of the answer given to Lorely Burt, Liberal Democrat MP for Solihull, this week to the Prime Minister in the weekly PMQs. But it sadly was not.

Clinical nursing specialists, including the well respected “Admiral nurses” from the ‘Dementia UK’ charity, have been recognised as being crucial to developing world class care in dementia too here from our own English nursing strategy. Over 4o00 have signed a petition for more Admiral nurses on the internet. A much under-reported item of research from the Centre for Innovation and Leadership in the Health Sciences at the University of Southampton, established improved clinical outcomes and significant return on investment from CNS in dementia. Again, work in progress suggests that the proactive case management approach has a lot to offer here. A paper from Prof Steve Iliffe and Prof Jill Manthorpe and colleagues is particularly noteworthy here. The beneficial impact of CNS in averting emergency admissions is being well described for cancer by Prof Alison Leary, Chair of Healthcare and Workforce Modelling, and colleagues (see, for example, here). If in the next five-year English dementia strategy there is a strong commitment to flagship clinical integrated services with well established and respected clinical nursing specialist models implemented, this could really revolutionise dementia service provision. And it’s now becoming increasingly that commonalities in what works well, especially in relation to involving caregivers, is working across a number of LTCs. This is a golden opportunity for senior policy specialists in dementia to put the emphasis on sustainable models of care rather than shiny box gimmicks, and to design a system which will be of real benefit to patients with dementia and their closest ones.

The World Dementia Council will be much stronger from democratic representation from leaders living with dementia

There is no doubt the ‘World Dementia Council’ (WDC) is a very good thing. It contains some very strong people in global dementia policy, and will be a real ‘force for change’, I feel. But recently the Dementia Alliance International (DAI) have voiced concerns about lack of representation of people with dementia on the WDC itself. You can follow progress of this here. I totally support the DAI over their concerns for the reasons given below.

“Change” can be a very politically sensitive issue. I remember going to a meeting recently where Prof. Terence Stephenson, later to become the Chair of the General Medical Council, urged the audience that it was better to change things from within rather than to try to effect change by hectoring from the outside.

Benjamin Franklin is widely quoted as saying that the only certainties are death and taxes. I am looking forward to seeing ‘The Cherry Orchard” which will run at the Young Vic from 10 October 2014. Of course, I did six months of studying it like all good diligent students for my own MBA.

I really sympathise with the talented leaders on the World Dementia Council, but I strongly feel that global policy in dementia needs to acknowledge people living with dementia as equals. This can be lost even in the well meant phrase ‘dementia friendly communities’.

Change can be intimidating, as it challenges “vested interests”. Both the left and right abhor vested interests, but they also have a strong dislike for abuse of power.

I don’t mean simply ‘involving’ people with dementia in some namby pamby way, say circulating a report from people with dementia, at meetings, or enveloping them in flowery language of them being part of ‘networks’. Incredibly, there is no leader from a group of caregivers in dementia; there are probably about one million unpaid caregivers in dementia in the UK alone, and the current direction of travel for the UK is ultimately to involve caregivers in the development of personalised care plans. It might be mooted that no one person living with dementia can ever be a ‘representative’ of people living with dementia; but none of the people currently on the panel are individually sole representatives either.

I am not accusing the World Dementia Council of abusing their power. Far from it, they have hardly begun to meet yet. And I have high hopes they will help to nurture an innovation culture, which has already started in Europe through various funded initiatives such as the EU Ambient Assisted Living Joint Programmes (“ALLADIN”).

I had the pleasure of working with Prof Roger Orpwood in developing my chapters on innovation in my book “Living well with dementia”. Roger is in fact one of the easiest people I’ve ever worked with. Roger has had a long and distinguished career in medical engineering at the University of Bath, and even appeared before the Baroness Sally Greengross in a House of Lords Select Committee on the subject in 2004. Baroness Greengross is leading the All Party Parliamentary Group on dementia, and is involved with the development of the English dementia strategy to commence next year hopefully.

Roger was keen to emphasise to me that you must listen to the views of people with dementia in developing innovations. He has written at length about the implementation of ‘user groups’ in the development of designs for assistive technologies. Here’s one of his papers.

My Twitter timeline is full of missives about or from ‘patient leaders’. I feel one can split hairs about what a ‘person’ is and what a ‘patient’ is, and ‘person-centred care’ is fundamentally different to ‘patient-centred care’. I am hoping to meet Helga Rohra next week at the Alzheimer’s Europe conference in Glasgow; Helga is someone I’ve respected for ages, not least in her rôle at the Chair of the European Persons with Dementia group.

Kate Swaffer is a friend of mine and colleague. Kate, also an individual living with dementia, is in fact one of the “keynote speakers” at the Alzheimer’s Disease International conference next year in Perth. I am actually on the ‘international advisory board’ for that conference, and I am hoping to trawl through research submissions from next month for the conference.

I really do wish the World Dementia Council well. But, likewise, I strongly feel that not having a leader from the community of people living with dementia or from a large body of caregivers for dementia on that World Dementia Council is a basic failure of democratic representation, sending out a dire signal about inclusivity, equality and diversity; but it is also not in the interests of development of good innovations from either research or commercial application perspectives. And we know, as well, it is a massive PR fail on the part of the people promoting the World Dementia Council.

I have written an open letter to the World Dementia Council which you can view here: Open letter to WDC.