Background: There have been numerous concerns that the health and care system in England is too fragmented, and lacks sufficient focus for a person with dementia or caregiver to navigate through the system.

A complex array of health and social care services is needed to support people living with dementia; “carers find navigating systemic issues in dementia care time-consuming, unpredictable and often more difficult than the caring work they undertake.”(Peel and Harding, 2014).

One of the “pillars” of the Scottish strategy invokes a “dementia practice coordinator“.

This rôle is: “a named, skilled practitioner who will lead the care, treatment and support for the person and their carer on an ongoing basis, coordinating access to all the pillars of support and ensuring effective intervention across health and social care”.

There are a number of possible professions which might be involved in this care coordinating role: for example, GPs taking a proactive approach to their patients, or social care practitioners who might have particular expertise in safeguarding issues (e.g. Manthorpe et al., 2007).

The Alzheimer’s Society suggest a “dementia adviser” role.

In this framework, the dementia adviser service would be ‘primarily for people with dementia, as well as their supporters and carers. It provides them with a named contact throughout their journey with dementia. Referrals to the service may come from GPs, CMHTs or other health and social care professionals, or self-referral.’

It is interesting to note that such a rôle was described clearly in the 2009 Department of Health English strategy document for dementia policy: “Living well with dementia”:

Clinical nurse specialists (CNS) in cancer perform a range of complex activities, including the management of care.

Recent evidence from the University of Southampton suggests that a properly trained and educated dementia specialist nurse, undertaking a clearly defined role, and working directly with people with dementia and their carers for a significant proportion of the time, could benefit people with dementia in hospitals. If these benefits addressed only a fraction of the excess stays experienced by people with dementia, a significant return on investment could be obtained.

CNS who practise proactive case management and refocus services in line with best practice represent a good return on investment (Leary and Baxter, 2014).

Recently, calls have been made to expand a pioneering dementia pilot in Norfolk after an almost £110,000 investment resulted in more than £400,000 savings for health and social services in less than a year.

The meaning of the term ‘timely diagnosis’ in dementia has recently come under close scrutiny.

For example, Dhedhi, Swinglehurst and Russell (2014) state that: “Reluctance or failure to make a diagnosis on a particular occasion does not necessarily point to GPs’ lack of awareness of current policies, or to a set of training needs, but commonly reflects this range of nuanced balancing judgements, often negotiated with patients and their families with detailed attention to a particular context.”

The Carers Trust has been working with the Royal College of Nursing to adapt the Triangle of Care to meet the needs of carers of people with dementia when that person is admitted to a general hospital. This approach, which has gathered some momentum in English policy, puts the person living with dementia in a ‘triangle of care’ in a ‘triangle of care’ with professional and carer (see page 6).

There is clearly a potential rôle for a third sector charity, such as Dementia UK, in providing clinical nursing specialist input. The success of Macmillan Cancer in the ‘prime contractor’ model for integrating cancer and end-of-life care in Staffordshire, as an example of outcomes-based commissioning, is, arguably, a very good recent paradigmatic example.

Aim: To conduct a preliminary online survey into citizens’ attitudes to what post-diagnostic support in the English jurisdiction could look like.

Methods: 87 respondents completed the online “Surveymonkey” survey, invited from a Twitter account with around 12000 followers. The survey could only be completed once.

You were invited to be a person who had just received a diagnosis of dementia in the English jurisdiction.

Exclusions: None.

Results:

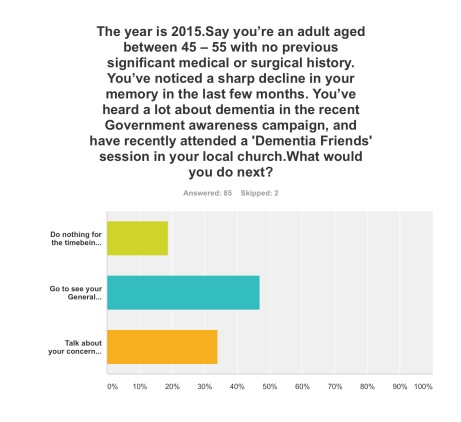

Q1. By far, the most preferred option was to go to see your General Practitioner with a view to receiving, if correct, a diagnosis of early dementia, if you’d noticed a decline in your memory and been aware of a public campaign on dementia (47%); talking about your concerns with your friends or family, to see what they suggest, was the next preferred option (34%).

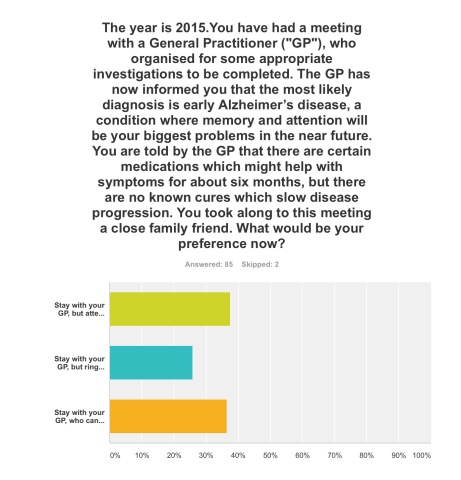

Q2. This was extremely finally balanced. One option was most preferred (38%), that of staying with your GP, but attending for the next couple of years regular six-monthly meetings with a hospital neurologist to observe follow-up with CPN support; but only just, as staying with your GP, who can help organise care and support for you and your closest consisting of a multidisciplinary team, was the next preferred option (36%). The option to stay with your GP, but ring up a local charity helpline to see what they can suggest to help you, regarding information and life choices, was the least preferred (26%).

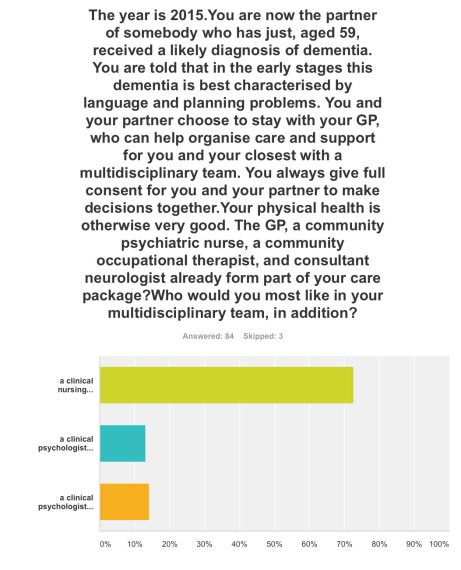

Q3. The option where a clinical nursing specialist had been added incrementally to a speech and language therapist and clinical psychologist was by far the most popular option (72%).

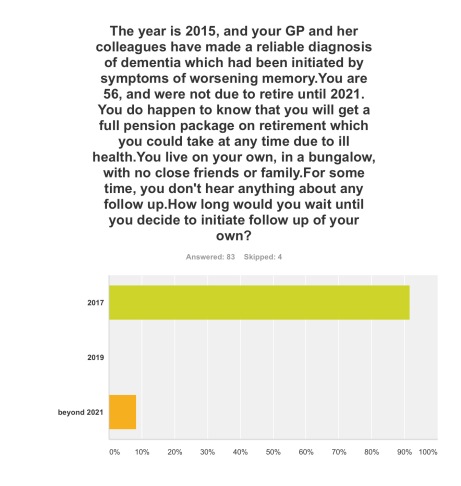

Q4. The option where you initiated follow-up for post-diagnosic support following diagnosis as soon as possible, relatively in 2017, was by far the most popular option (92%).

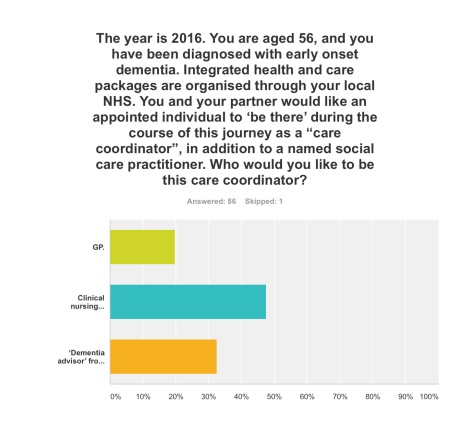

Q5. Three options were given for who the ‘care coordinator’ could be. A clinical nursing specialist was by far the most preferred option (48%), then ‘dementia adviser’ from a well known charity (33%), and then the GP last (19%).

The rôle of the ‘dementia adviser’, particularly at the earlier stages of the condition at least, is clearly worth considering in future policy such as the English dementia strategy 2015-20.

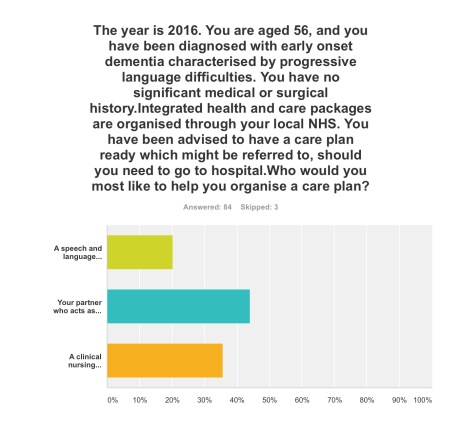

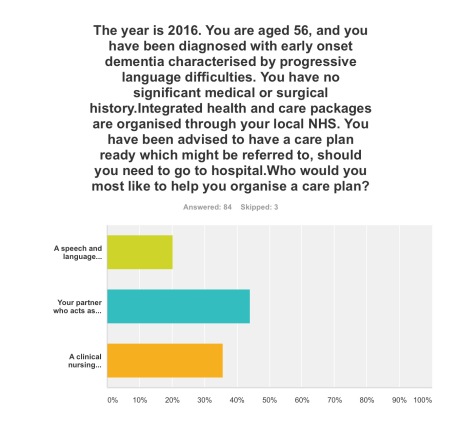

Q6. This question asked who you would like the most to organise your care plan with you: your primary caregiver was the most popular choice (44%), with a clinical nursing specialist the next popular choice (36%).

Q7. Here it was introduced that a clinical nursing specialist was one of the options in the new English dementia strategy (2015-20). The rationale for this, most felt, should come from clinical outcomes (76%), then financial considerations from the funding situation of the NHS and care (14%). The option where powerful lobbying from charities (“third sector”) should be the driver for specialist nurses was the least preferred (10%).

Discussion: The results confirm previous anecdotal reports of the need for timely post-diagnostic support following ‘timely diagnosis’. They paint a picture of a person who has become aware of dementia awareness campaigns and noticed possible symptoms in himself wishing to trust to see a General Practitioner to receive a diagnosis. On receipt of that ‘timely diagnosis’, he or she would be keen to initiate post-diagnostic support as soon as possible, with a multidisciplinary team; it is striking that a clinical nursing specialist was preferred to the rôle of the ‘dementia adviser’ from a charity previously mooted; and that the decision in policy to implement clinical nursing specialists should be made on the basis of clinical outcome, not financial pressures in which the NHS and care find themselves. Notwithstanding that, the results support heavily a ‘triangle of care’ involving a caregiver and a professional, such as a person living with dementia, in the formation of a personalised care plan.

Limitations: There are no geographical data of the locations, or other demographic data, of the respondents to this online survey. Responses might be biased by the nature of the Twitter threads which had invited respondents to participate, or the nature of the followers of those threads. The questions assume a working knowledge of what the key personnel in a multidisciplinary team for dementia care and support do.

Although respondents were advised to select one of the options, however inadequate the options were, it is a limitation of this study that options did not include social care practitioners. Social care practitioners will, however, have a critical rôle in dementia post-diagnostic care and support.

Conclusions: The findings taken together provide important considerations for future policy-makers regarding post-diagnostic support for dementia in the English jurisdiction, urging the need for a rôle for clinical nursing specialists in delivering prompt post-diagnostic support and in avoiding, on the basis of clinical need, inappropriate care in hospitals.

Selected readings

Carers Trust/Royal College of Nursing. (2013) The triangle of care. Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice for Dementia Care

Dhedhi SA, Swinglehurst D, Russell J. (2014) ‘Timely’ diagnosis of dementia: what does it mean? A narrative analysis of GPs’ accounts, BMJ Open, Mar 4, 4(3):e004439.

Leary A, Baxter J. (2014) Impact of lung cancer clinical nurse specialists on emergency admissions, Br J Nurs, Sep 25, 23(17), pp. 935-8.

Manthorpe J, Clough R, Cornes M, Bright L, Moriarty J, Iliffe S; OPRSI (Older People Researching Social Issues). (2007) Four years on: the impact of the National Service Framework for Older People on the experiences, expectations and views of older people, Age Ageing, Sep, 36(5), pp. 501-7.

Peel E, Harding R. (2014) ‘It’s a huge maze, the system, it’s a terrible maze': dementia carers’ constructions of navigating health and social care services. Dementia (London), Sep, 13(5), pp. 642-61. d