Home » 2014 (Page 6)

Yearly Archives: 2014

Developing an enhanced person-centred speech and language service for persons living with PPA dementia

Ravel, composer of ‘Bolero’, who died in 1937, is thought in retrospect to have lived with PPA dementia.

The direction of travel is to develop a person-centred service for people living with dementia and their closest including primary caregivers.

There is still much interest in demonstrating beneficial outcomes, despite the scarcity of resources.

Reports are currently that speech and language input not only can improve communication in people living with PPA, but can improve wellbeing for all involved.

The current NICE guidelines (2011) make it clear that speech and language therapists have a vital role in assessment and management for people with communication difficulties as a result of dementia.

Yesterday, it was very nice to go to the PPA Support Group, this time hosted at UCL off Gower Street.

I was there with my friend Charmaine Hardy whom I had first met on Twitter through Beth Britton.

The “team” is here.

Members of the Queen Square cognitive disorders service are known to me.

Giovanna Mallucci, Jason Warren and Nick Fox were all my Specialist Registrars there – on Prof Martin Rossor’s firm – when I was the equivalent of a FY2 Doctor more than a decade ago. They now are all currently Professors (Jason and Nick at the National Hospital for Neurology and UCL Institute of Neurology).

I had a long chat with Katy Judd, the highly experienced specialist nurse on this firm. I have memories of Katy being completely wonderful. And she was wonderful yesterday. For me, there was a huge deal to catch upon.

The PPA newsletter, containing details of their activities, is here.

Anna Volkmer is a specialist speech and language therapist, from the prestigious South London and the Maudsley NHS Trust.

Anna is on a crusade to go from raising funds for much needed research to developing an innovative, and very much needed, service.

Anna gave a very clear presentation of her research looking at the efficacy of therapy techniques in PPA. A questionnaire survey had revealed that there was much interest in local specialists.

Sessions before the therapy were recorded. Each session was about one hour long.

The aims of therapy for each person and caregiver were different and tailored to the individual.

For example, Anna gave an example of Mr and Mrs G. Mrs G had reported much frustration with her difficulty in communicating, and her perception that Mr G ‘didn’t wish to listen any more’.

Persons with dementia (Frontotemporal Dementia- Primary Progressive Aphasia type) who have been assessed by the St Thomas’ memory clinic team (in the South London and Maudsley NHS Trust) and been referred to a highly specialist speech and language therapist.

The evidence to date had suggested that single word therapies focusing on rehearsal and semantic tasks are most likely to support maintenance of communication for people with PPA (e.g. Jokel, Rochon & Leonard, 2006).

Intervention focused on identifying communication breakdown between the person living with PPA and their communication partner using video-feedback.

One member of the audience described how he had accompanied his wife, living with PPA dementia, to a specialised speech and language unit in Chicago. This unit is apparently world-renowned, known to Anna. The delegate’s experience had been extremely positive.

Anna will be presenting at the British Aphasiology conference later this year, and has a long standing interest in PPA , having written and published on the subject.

Anna’s book on PPA – which she mentioned in the Q&A session – is here.

We then sat around in round table discussions, focused around subtypes of PPA.

Charmaine and I were on the ‘logopenic PPA’ table.

The initial characterisations of a “logopenic” (from Greek, meaning “lack of words”) presentation of PPA described an overall paucity of verbal output, with relative sparing of grammar, phonology, and motor speech,

More specialised information about this type of PPA – meant for a specialist audience – is here.

We discussed various aspects.

One was how it would be a great idea to involve friends or family early on, to help with communication with services from an early stage.

We also discussed how good it was to capture communication intervention techniques on video, so that analysis could also be conducted for non-verbal communication.

We discussed how both hospital and bome settings could be useful for such ‘roll out’ of the service. More research was needed how many sessions there could be, what the time intervals between each session might be, and how early on in the condition the service should take place.

A number of families had had access to speech and language services. The ‘quality’ of such services varied in style and content.

It was observed that speech and language therapists often were keen to administer tests rather than to build up a person-centred or relationships-centred rapport. However, Charmaine Hardy described how her husband had been investigated using an extensive biography approach. Charmaine is on Twitter (@charbhardy), and her profile states indeed her husband, whom she cares for too, lives with PPA dementia.

We talked about how the numbers of people living with PPA dementia were few in number in disparate localities, but how expertise could be pooled for the benefit of persons and families. Our group felt that a coherent PPA information provision, strategy, perhaps organised in both a generic and an individualised person-centred way, could be enormously helpful in service provision.

It was felt that one hour was long, possibly a bit too long provided there was an adequate number of ‘breaks'; but delegates on my table emphasised that each person was different.

References

Jokel, R., Cupit, J., Rochon, E. and Leonard, C. (2009) Relearning lost vocabulary in nonfluent progressive aphasia with MossTalk Words. Aphasiology 23 (2) 175 -191.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health commissioned by the Social Care Institute for Excellence National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (revised 2011) CG 42.

You need risk to live well with dementia

“Risk” is one of those entities which bridges the financial world with law and regulation, psychology or neuroscience. The simplicity of the definition of it in the Oxford English Dictionary rather belies its complexity?

It was a pivotal part of my own Ph.D. in the early diagnosis of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia, awarded by the University of Cambridge in 2001. I was one of the very first researchers in the world to identify that ‘risk seeking behaviour’ is a key part of the presentation of many of these individuals, against a background of quite normal other psychological abilities and investigations including brain neuroimaging scans.

‘You need to break eggs to make an omelette’ is one formulation of the notion that you have to be able to make mistakes to achieve an overall goal. That particular sentence is, for example, used to convey the way in which you might have to put up with ninety nine turkeys before striking gold with one truly innovative idea. ‘Nothing ventured nothing gained’ is another slant of a similar idea. Interestingly, this phrase is often attributed to Benjamin Franklin. Franklin has an established reputation of his own as a ‘conceptual innovator‘.

It’s also a very interesting policy document on risk in dementia from the UK Department of Health, from 10 November 2010, a really useful contribution. This guidance was commissioned on behalf of the Department of Health by Claire Goodchild, National Programme Manager (Implementation), National Dementia Strategy. The guidance was researched and compiled by Professor Jill Manthorpe and Jo Moriarty, of the Social Care Workforce Research Unit, King’s College London.

Prof Alistair Burns, England’s clinical lead for dementia, has written a very focused and relevant Foreword to this piece of work. Here Alistair is, pictured with me earlier this week at the Dementia Action Alliance Annual Conference hosted in Westminster, London (“DAA Conference”). The event was a positive celebration of the #DAACC2A, “Dementia Action Alliance Carers’ Call to Action”, which embodies a movement where, “carers are acknowledged and respected as essential partners in care, and are supported with easy access to the information and the advice they need to assist them in carrying out their role.”

Risk enablement, or as it is sometimes known, positive risk management, in dementia involves making decisions based on different types of knowledge. However, people living with dementia and caregivers, quite often an eldest child or spouse, can handle risk in different ways. I feel that understanding living well with dementia is only possible through understanding the background to a person living with dementia, and his or her interaction with the environment. I’ve indeed written a comprehensive book on it, and I am in the process of writing a second book on it, which brings under the spotlight many of the key stakeholders, I believe, who contribute to “dementia friendly communities”.

Risk enablement is based on the idea that the process of measuring risk involves balancing the positive benefits from taking risks against the negative effects of attempting to avoid risk altogether. For example, the report cites the example of the risk of getting lost if a person with dementia goes out unaccompanied needs to be set against the possible risks of boredom and frustration from remaining inside. There are clearly various components of risk which might affect a person living with dementia. Risk engagement therefore becomes a constructive process of risk mitigation, an idea highly familiar to the law and regulation through the pivotal thrust of ‘doctrine of proportionality‘, that legislation must be both necessary and proportionate.

Risk enablement, it is argued, goes far beyond the physical components of risk, such as the risk of falling over or of getting lost, to consider the psychosocial aspects of risk, such as the effects on wellbeing or self-identity if a person is unable to do something that is important to them, for example, making a cup of tea. Therefore, the report proposes that “risk enablement plans” could be drawn up which summarise the risks and benefits that have been identified, the likelihood that they will occur and their seriousness, or severity, and the actions to be taken by practitioners to promote risk enablement and to deal with adverse events should they occur. These plans need to be shared with the person with dementia and, where appropriate, with his or her carer or caregiver. Thus advancing the policy construct of ‘personalisation’ offering choice and control, risk assessment tools are envisaged by the authors to help support decision making, and should include information about a person with dementia’s strengths and of his or her views and understanding about risk. Risk could apply to making a cup of tea, or going for a walk. We know that people living with dementia handle risks in different ways. For some people, a person living with dementia excessively walking beyond a local jurisdiction might be a known problem. For all the different causes of dementia medically, and for all the different ways in which individuals react to a dementia at different stages of the condition, a person can live with dementia in a sharply distinctive way.

Risk therefore in a hugely meaningful and substantial way has moved away from the “safety first” circles? And it fundamentally will depend on how an unique person living with his or her dementia embraces the environment in reality.

The idea that you need risk to live well with dementia is brought into sharp focus here by Chris Roberts, a friend of mine, speaking at the DAA Conference. I have recently begun to take risks in a highly enjoyable game for my #ipad3, which Chris indeed introduced me to, called, “Real Racing 3″. Here, Chris also talks about the crass way in which he was originally told his diagnosis, and lack of information about his condition given at the time of diagnosis. Therefore, Chris, I feel, brings into sharp focus a number of problem areas, which hopefully Baroness Sally Greengross and colleagues will address in a new five year strategy for England for 2015-20.

Is there more to influencing English dementia policy than putting up a poster?

Now is the time to influence the new English dementia strategy. It is critically important that the informed opinions of a diverse group of stakeholders are involved in framing this policy.

As with any strategy document, it will be hard to be in full control of all of the facts and evidence, but I feel it’s very important that the views of people living with dementia are taken into account. This is not just a case of ‘involving’ people living with dementia where possible. It’s a case of allowing people living with dementia to lead in framing the narrative. I am not going to suggest what these topics might be. I think, for people with more advanced dementia, it is going to be important to listen to the views of carers, both unpaid and paid. There is currently a huge policy problem that the needs of carers themselves are unaddressed. Carers need to be better supported in a more structured way.

There has also been a problem rumbling on years: that people who’ve received a diagnosis of dementia are not signposted to appropriate services. While the job description of ‘dementia adviser’ was mooted, I don’t feel this goes nearly enough. The ‘Dementia Challengers’ website, through amazing personal efforts from its one-person designer who has personal experience of this field, offers useful leads on support for making informed choices for living well with dementia. There is no escaping the overwhelming desire, also, to see a system of specialist nurses participating in a care system. Also, we are not making use of the substantial expertise of social work professionals. For issues such as advocacy over capacity and liberty, there are certain people with dementia who need to have equitable access to such resources.

I am a card-carrying signatory that each person living with dementia has an unique experience. I’ve even written a book on it. But it might help people with certain types of dementia to be reassured that there are clinicians with expertise in dementias, and can promote certain support groups (such as the excellent PPA Support Group). We need any diagnosis of dementia to be correct. I too often hear of people being given a diagnosis from somewhere, on the basis of a very scanty work-up. I understand the concerns that too many people are being denied of a correct diagnosis, but we must ensure that this part of the system is adequately resourced. It is possible there will be a breakthrough in drug development for the dementias in the near future. I wish the people working on this well. I am sure that they will not wish resources to be diverted disproportionately into this away from current care, or making it appear that the current living well of people with dementia is less of a priority?

The ‘dementia friendly communities’ policy plank is potentially fruitful. However, I think we should address how we hear a lot from corporates, but not much, in this jurisdiction, from professionals and practitioners who could be useful members of that community. Under the current legislative framework, both in domestic and international law, the rules of equality and human rights apply. These are not issues only for the ivory towers. They have direct relevance to the person with younger onset dementia who finds himself in an unfair dismissal situation. They also have relevance to the person in the badly run care home who feels (s) he is subject to “degrading treatment”. Access to the law has been a real setback for the current Government, as has been access to see your GP. These create the perfect storm for a ‘dementia unfriendly community’.

I am the last person to denigrate the efforts of the vast army of people putting up posters, signing petitions, or handing out leaflets, in the name of ‘dementia awareness’. There is a huge danger that these posters, petitions and leaflets send out a message of ‘mission accomplished’, if there is no follow up? But I am likewise a bit burnt that the fact that #G7dementia and “Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge” appeared from nowhere, and had the effect of threatening plurality in the dementia third sector. I am concerned about this, and now is the time to make views known to the Baroness Sally Greengross, Chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group, Prof Alistair Burns, the clinical lead for dementia in England, and Prof Martin Rossor, lead for research for dementia for NIHR.

The Tory pitch on the NHS is based on two innocent misrepresentations. They’re huge – like the debt.

A perfect way to annoy nurses is to promise a tax cut for people with the highest incomes ahead of a release from the pay freeze most nurses have endured for the last few years.

I’ve noticed a curious phenomenon when I retweet articles on Twitter. It is not a secret that I am ‘left wing’, whatever that means to the intelligentsia of North London. If I retweet an article from the perspective of how awful this Government, by a left wing ‘seleb’, it won’t be uncommon for people to think ‘nothing to see here, please move on’ . But, if I share something by Fraser Nelson or Isabel Hardman, all hell breaks lose.

Take, for example, the article by Nelson criticising the burgeoning debt burden, published in that well known leftie rag, “The Spectator”. It’s a refreshing honest piece of journalism entitled, “Osborne increases debt more than Labour did over 13 years“. I suspect both Ed Miliband and David Cameron were more prepared for the scenario if Scotland had voted ‘yes’ to independence. Most people I know felt that the story of Ed Miliband’s walk in the park was totally underwhelming. David Cameron, in an outbreak of honesty, meanwhile, let slip that he “resented” the poor. This, for me, represents a clear example the “don’t think of elephants” phenomenon. The harder you try not to think of something, you think of it.

Once, at the Labour Conference held in Liverpool (2011), I asked Jim Naughtie about this famous episode.

Both Naughtie and I burst out laughing. Jim Naughtie is of course not the first person to have dropped a massive clanger. Everyone, including Andrew Neil and Nick Robinson, knows that the pitch by the Tories on tax cuts, when the deficit is being given a second chance to resolve itself, this time by 2018, is a total farce.

I had barely got over the admission that Cameron resented the poor when this suddenly happened.

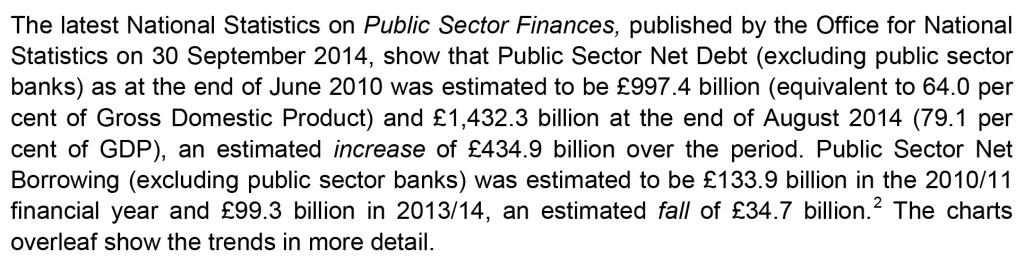

This is a colossal lie, as Sir Andrew Dilnot CBE, Chair of the UK Statistics Authority, has explained to Chris Leslie MP, the Shadow Chief Secretary to the Treasury, in his letter. The critical paragraph of that letter is this.

Even a PPE graduate from Oxford can begin to get the gist from this graph helpfully provided by Dilnot.

Similarly, because of inflationary pressures – including increasing service demands – on the NHS budget, it is difficult to argue that in real terms there has been an increase in funding of the NHS. That one is also colossal lie, as Sir Andrew Dilnot CBE, Chair of the UK Statistics Authority, has explained to Jeremy Hunt MP, Secretary of State for Health, in his letter here. The critical paragraph of that letter is this.

The Conservative pitch logic is as follows: (1) the Tories are trusted on the economy, (2) Labour is trusted on the NHS, (3) Discredit Labour by repeatedly talking about Mid Staffs despite clearly enduring problems in the lifetime of this period of office, (4) Promise tax cuts in 2018 and ‘more for less’ (by citing examples such as falling crime despite budget cuts). But this logic is based on a surfeit of lies and half truths.

It is a curious phenomenon that crime statistics keep on falling across a number of jurisdictions, fitting very nicely with the argument by libertarians for a smaller state. Furthermore, NHS England has reported on poor recent performance, following the time of the Mid Staffs disaster, in the “Keogh Trusts” during the lifetime of this period of a Conservative-led government. Andy Burnham MP does not repeatedly bring up the example of Harold Shipman, a colossal failure of regulation of general practice which happened instead under the lifetime of a previous Conservative government. It’s been repeatedly reported that Labour ‘do not appear to want to be in power despite being on the brink of power’. But, by that token, the Conservatives are behaving as if they realistically do not expect to be the largest party next May, either. The Conservatives-led Government decided not to take up a golden opportunity of regulating clinical professions, handed on a plate by the English Law Commission, in the last Queen’s Speech of this term. The General Medical Council even signalled their disapproval of this. And, as alluded to above, the debt is exploding while NHS demand continues to increase, leaving a ‘funding gap’ which has been brilliantly discussed by ‘The Health Foundation’. Once again, the patriotic Conservative Party have stuck two fingers up at the best interests of the country by currying favour with their high income (and wealthy) backers, instead. The “jam tomorrow” argument from the Conservatives could be fatal to a frank discussion of the need to integrate health and care from the next Government, whoever it is. But, as my late father often used to remind me, “one lie leads to another”.

Time to turn to the “Black Eyed Peas” for inspiration perhaps.

Sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry

Hey, baby my nose is getting big

I noticed it be growing when I been telling them fibs

Now you say your trust’s getting weaker

Probably coz my lies just started getting deeper

And the reason for my confession is that I learn my lesson.

NHS “credibility gap”

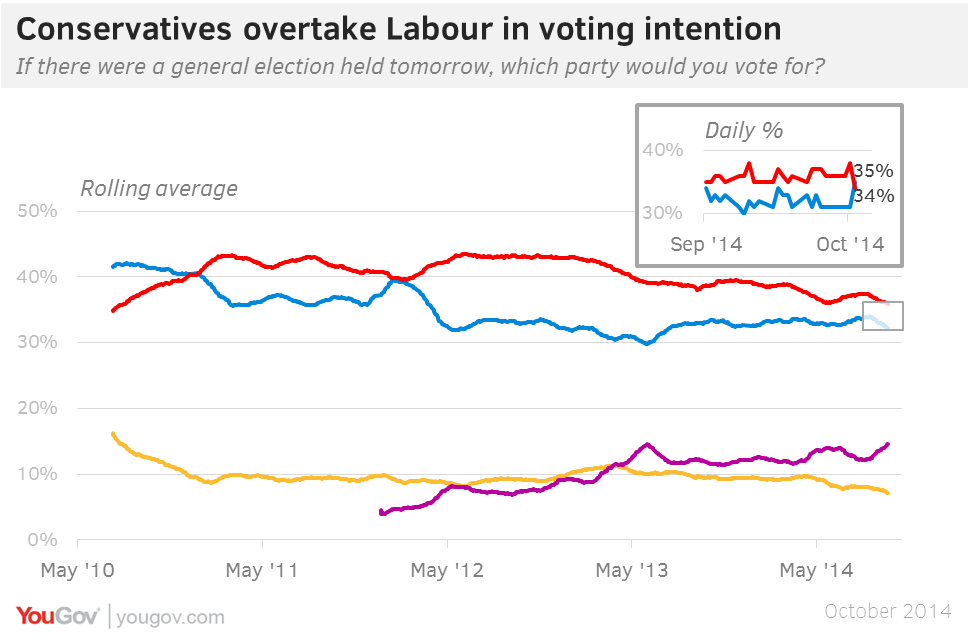

The Conservatives have overtaken Labour for the first time since March 2012 in the latest YouGov/The Sun poll.

David Cameron has an inherent advantage in the public perception’s of his leadership qualities, in that he is doing the job every day and being seen to do so on the news. Credibility is an important currency. And Labour has already stated ‘the market went too far’ in the NHS. It is not a secret that many parts of the media try to present Ed Miliband in a negative light. Labour is trusted on the NHS, and the Tories are trusted on the economy; so a rationale strategy for the Tories is to make the link between the country’s economy and the NHS. However, real-terms NHS funding has effectively flatlined for a number of years now, not keeping up with the inflation in the system, and debt under this Government has got out of control.

For example, you’re more likely to get a discussion of the ‘bacon butty’ incident than a discussion of how NHS contracts have been aggressively been promoted to the private sector, or how the Health and Social Care Act (2012) locks in the market.

The Prime Minister often blames this lack of coverage on the era of the rolling news, but conversations in the social media have been very productive in exposing events which the BBC would rather not cover. David Cameron’s segment on the NHS was certainly passionate. Cameron must have been distraught at the closure of the Cheyne Centre which he had once fought to keep alive.

But actions speak louder than words. When Cameron claims he will protect the NHS he doesn’t say from whom or what he needs to protect it. He no longer talks about the importance of competition in the NHS and many of the initiatives associated with Andrew Lansley seem to have been quietly forgotten.

If David Cameron had wanted to win the trust of the medical profession, he would not have ambushed them out of nowhere with a ‘top down reorganisation’ which he promised would never happen. The £2.4 bn reorganisation is widely considered to be a tragic waste, when money could have, and should have, been invested in frontline services. The chunk of the speech on the NHS was little consolation to hardworking nurses who’ve witnessed yet another pay freeze, despite the economy’s performance recovering. Nurses, part of the lifeblood of the service, are not immune from the ‘cost of living crisis’, particularly if they are living in London and working in one of the powerhouse teaching hospitals.

A&E targets have been consistently missed during the duration of this period of office by the Conservative Party (and the Liberal Democrat Party).

The current Government need to address what to do about the ‘private finance initiative’. New contracts have been awarded during the lifetime of this Government, and, whilst they were undoubtedly popular under New Labour, their origin is clearly found in the John Major Conservative administration of 1992-1997.

David Cameron, in his conference speech, simply behaved so passionately about the NHS as if the Lewisham debacle had never happened. The current Government even spent money trying to win the case in the Court of Appeal.

GP waiting times have been an unmitigated disaster under this Government. There has been a marked rise in the number of NHS trusts in deficit. Jeremy Hunt is stuck in a time warp. He mentions Mid Staffs at every opportunity. Hunt, completely disingenuously, does not let the failures in culture, quality or management, identified at the CQC, soil his lips. The “Keogh Trusts” were dealt with due to failings which had occurred in the lifetime of and due to this government.

Like the referendum on Europe, promising ‘to protect’ the NHS could be ‘jam tomorrow‘, if the Conservative Party fail to get re-elected. It is either a sign of confidence, or sheer arrogance, that David Cameron and colleagues can hang these uncoated promises in thin air.

The position in an editorial of the Financial Times is clear – and damning:

“But in the bid both to draw a clear dividing line with Labour and reassure the wavering right, they have staked out a fiscal position that is neither sober nor realistic.”

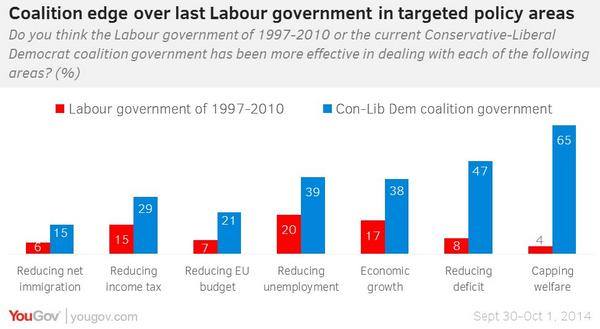

And, hard though it might be to swallow, the Coalition appears to have an ‘edge’ on some key policy areas.

Labour would never have been able to get away with such dodgy promises, with their plans for government being watched like a hawk. With the help of the BBC and other supine media outlets, rather, there will be an inadequate scrutiny of these Conservative plans, which hopefully will be better articulated before the time of the election. As such, it does not matter what Labour promises its voters on the abolition of the purchaser-provider split, whole person care, the private finance initiative, reconfiguration of hospitals, GP waiting times, patient safety, and so on, if voters wish to vote for ‘jam tomorrow’.

The hope is that a Secretary of State for a Labour government would be able to untangle the UK government out of TTIP and CETA trade agreements further giving propulsion to neoliberal forces attacking the NHS. There is a hope that health and care finances will be properly funded in the next Government. All parties have arguably failed to have this conversation with the general public thus far.

Some policies of the current Conservative-led administration are incredibly unpopular with Labour voters: e.g. welfare benefits, NHS privatisation, repeal of the Human Rights Act. The feeling of many, currently, is that, while they do not particularly like this Government, they do not wish to vote for Labour which appears to be offering a diluted form of what the Conservative Party is offering. This is not in any way a indictment of the sterling efforts of the Labour Party Shadow Health Team.

But, before Labour attempts to plug the ‘funding gap’, it will need to resolve any ‘credibility gap’ first.

Scrapping the Human Rights Act does not get rid of Strasbourg as a portal of action for health and care matters

Like most people who’ve had a legal training, I was baffled why David Cameron is so triumphant about scrapping the Human Rights Act (1998). The legal position is that “British citizens would still be able to take cases to the European court of human rights, and its case law and the principles of the convention would still be in force in UK courts.”

This is stated correctly here.

Leading commentators such as Joshua Rozenberg, Britain’s best known legal commentator, have previously advised that the debate must be conducted in a different light from the political grandstanding (article here).

When Dominic Grieve, the previous Attorney General, was asked at a fringe meeting for his reaction to May’s speech, he insisted he was “completely comfortable” with the idea of replacing the existing legislation with a British bill of rights.”

At the time, it was observed that Ken Clarke QC MP, like Dominic Grieve QC MP, was a keen supporter of human rights.

In 2011, when I was studying my Master of Law, I attended discussion at the Honourable Society of Inner Temple last night. The seminar is jointly hosted by the Constitutional and Administrative Bar Association (ALBA) and the new Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law. The speakers included Lord Justice Laws, Lord Pannick QC and Professor Philip Leach, London Metropolitan author, and author of numerous publications including the book “Taking a case to the European Court of Human Rights”. The session was totally packed out, and the speakers took many questions from leading practising international barristers and academics.

It is perhaps easy to overstate the opposition towards the Human Rights Act, but it was pointed out only two countries are openly questioning the legitimacy of the European Convention of Human Rights – Russia and the United Kingdom.

LJ Laws has long been in favour of developing domestic jurisprudence in the context of the Human Rights Act and common law.

He opined at this event that “the cases were beginning to speak, but the Convention was an useful guidance”, and reaffirmed the influence of a graduated approach to proportionality, an argument which Laws noted had been accepted by Bingham (see for example Regina v. Secretary of State For The Home Department, Ex Parte Daly). Laws reminded the legal audience that we, as a country, have always been in a position to influence Strasbourg, as for example the Pretty v United Kingdom case.

Laws further mooted, however, why should the judges be deciding upon social policy. Considering particularly articles 8-12, Laws provided that often lawyers had to decide where to strike the balance in certain issues between competing interest, but fundamentally lawyers were there to establish the framework and issue – however Laws warned that the nature of this exercise in jurisprudence gives rise ultimately to issue of a philosophical nature. I found this academic exploration by Laws interesting in light of how human rights law might impact on aspects of health and care policy in England.

Lord Pannick charted the history of the reaction to our history right legislation, in relation to Strasbourg. Pannick reminded the audience that criticising the Human Rights Act, in relation to Europe, was not a recent phenomenon.

In relation to the Gilbraltar incident, Michael Heseltine – as far back as 1995 – said, “We shall do nothing. We will pursue our right to fight terrorism to protect innocent people where we have jurisdiction, and we will not be swayed or deterred in any way by the ludicrous decisions of the Court.”

According to Lord Pannick, prisoners’ voting rights and the use of hearsay have also produced conflicting opinions from the UK and Strasbourg, and indeed these legal conflicts appear to be ongoing (see for example the present case of Zainab al-Khawaja, where the original argument was heard by the Court in 2010).

Lord Pannick proposed that this conflict arose from various sources. Firstly, Lord Pannick felt there is a general resentment of European law amongst Conservative “elements”, and many of the population. Secondly, the objection to the European Convention of Human Rights could part of a wider objection to foreign law. Lord Pannick indeed reminded the audience that a Conservative MP, lawyer and judge, David Maxwell-Ffye, was instrumental in drafting the European Convention of Human Rights. Lord Pannick then identified a possible perception from the UK voting public, that judges should not be deciding on social policy: for example, the argument for prisoner voting is not a matter for judges, but should be a matter for parliament.

Lord Pannick did not feel fundamentally that the criticisms of the HRA amounted to much. For example, the HRA expressly recognises that the UK Parliament is not bound by the Convention. If Parliament wishes to exclude voting by prisoners, the Human Rights Act does not prevent this. The judges can decide whether the defendants comply, but, according to Lord Pannick, it is equally important that the last word lies with parliament. Lord Pannick instead felt that a much more difficult issue is the relationship between parliament and the Strasbourg Court.

A future ‘all Conservative’ government, even if it repealed the HRA would still leave the jurisdiction of the Strasbourg Court intact – our own judges have no effect on the jurisprudence.

If the 1998 Act were to be repealed, as parliament is overeign, the number of British cases to Strasbourg would increase according to Lord Pannick. Lord Pannick felt that an useful to look at the relationship between our Supreme Court and Strasbourg would be to look at the ‘control of its docket’ jurisprudence, in other jurisdictions of international law.

Lord Pannick ultimately felt that the power of our parliament to define power Strasbourg as a body is limited. It would be unprecedented for us to withdraw from the European Convention of Human Rights, incompatible with membership of the EU, or Council of Europe. According to Lord Pannick, the concept of European minimum standards is of vital importance to us. There may be be occasions when national or international considerations are that our judges do not originally recognise that human rights are being breached (e.g. gays in the military) It would be difficult for us to expect that other countries such as Russia should comply with the Convention, if we do not. Lord Pannick therefore felt that the situation now required an accommodation on both sides.

The Strasbourg is supposed to overrule a National court only in cases of fundamental significance, where the national supreme court has made an error of principle. If Strasbourg does not follow this principle, it may risk the growth of political opposition. However, likewise, Lord Pannick identified that the Supreme Court should not supinely follow Strasbourg, either. The Government for example accepted the DNA ruling in preference ot the House of Lords. If the Supreme Court were to be asked if the voting rule asked about the prisoners’ voting again, Lord Pannick felt that the Supreme Court would be unlikely to say it is compatible with the European Convention of Human Rights.”

The Human Rights Act (1998) is also relevant to aspects of policy relating to people’s health: there have been concerns whether the ‘welfare reforms’ have offended human rights legislation.

There have also been concerns whether the fitness to practise procedures of the GMC need to be explored with the human rights lens?

There are also further issues, unresolved as yet, about whether the Health and Social Care Act (2012) offends humans rights legislation.

Most of this blogpost was first published on Dr Shibley Rahman’s legal blog here.

Why two’s company, and three’s a very good thing, for English dementia policy

There’s an old-fashioned idea that the only relationship which matters is the one between the person living with dementia and the medical Doctor. I completely sympathise with the concern surrounding the idea ‘we are all patients now’, where, for example, people experiencing memory problems as a natural part of ageing get overmedicalised as ‘dementia’, perhaps for the purpose of hitting a national target: that well people are in fact the undiagnosed ones. But, likewise, my own experience as a person living with physical disability is that we are all persons who become patients at the point of becoming ill. I therefore think the term ‘patient leader’ is outdated, unless there is a specific group of people who only consider themselves ill.

I am not a ‘believer’ that I belong in an interconnected world by virtue of the fact that I have a Facebook account, but I do feel part of a wider network of knowledge, behaviours and skills. I feel that I can draw on this talent if I need support in me living independently, or care if I have unaddressed needs. When I could barely speak and move, soon after my meningitis, I was helped by a carer who is in fact to this day is one of my best friends. For too long, carers, I feel, have been airbrushed out of the picture. The clue is in the name ‘Whole Person Care’. Carers matter, and they should be given the prestige and status they so strongly deserve.

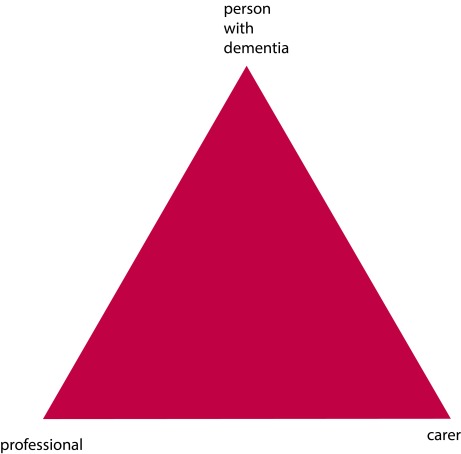

The landscape is though gradually changing, for the better. The “Triangle of Care” describes a therapeutic relationship between the person with dementia (patient), staff member and carer that promotes safety, supports communication and sustains wellbeing (Carers Trust, 2013). Carers often report that their wish to be effective often compromised by failures in communication, possibly because some people are unwilling listen.

At critical points, carers can be excluded by staff, and requests for helpful information, support and advice are not acted upon. Sadly we need to address the fact that medical professionals need specific training in working with carers, not working against them. This needs to include training in communication strategies with people with dementia, thus enabling people with dementia to be engaged for as long as possible.

redrawn from Carers’ Trust [Triangle of Care]

We currently have a dearth of research of this triangular relationship – but plenty on the ‘dyadic’ relationship between professional and carer. Most studies on patient–physician relationships and communication have focused on the dyadic interaction between the parties and the type of exchanges occurring among them. However, up to 60 percent of medical encounters involving elderly persons are threesomes (Adelman, Greene and Charon, 1987). The features of such relationships differ fundamentally from those of a dyad. The very presence of a third person may affect the basic patient–physician relationship (Kealy and Nolan, 2003) negatively by limiting patients’ involvement and assertiveness or actual exclusion from the care discussions (Greene et al., 1994), or positively by enhancing physician–patient communication and consequently superior comprehension and involvement by accompanied rather than unaccompanied patients (for example Clayman et al., 2005).

A person coming into contact with the health and care services currently do so from the point of a possible diagnosis. Results from the study from Zaketa and Carpenter (2010) were also actively seeking evaluation of their cognition and were subsequently diagnosed relatively early in their disease progression appear to suggest that physicians do not utilise patient-centered behavious such as emotional rapport building at first. Only once patients and caregivers are experiencing and demonstrating overt distress associated with more severe symptoms, or as physicians are delivering more dire news regarding the patient’s prognosis and ability to live independently, does a three-way relationship begin to kick in. Hubbard and colleagues (Hubbard et al., 2009) had concluded that carers are involved in treatment decision-making in cancer care and contribute to the involvement of patients through their actions during, before and after consultations with clinicians. Carers can act as funnels for information from patient to clinician and from clinician to patient. They can also act as facilitators during deliberations, helping patients to consider whether to have treatment or not and which treatment.

And English dementia policy can learn usefully not only from cancer. In paediatrics, De Civita and Dobkin (2009) revisited the term “triadic partnership”, in referring to “the therapeutic triangle in medicine that includes the caregiver, child, and medical team in facilitating adherence to treatment”. Optimal health, one may argue, is achieved when patients, caregivers, and health care providers collaborate in designing a manageable treatment program (Rapoff, 1999). This in time may impact on the policy for self-care. According to Strachan and colleagues, a better understanding of the individual factors that influence heart failure self-care is necessary for interventions to be more responsive to the needs and preferences of patients (Strachan et al., 2013). Individual factors known to affect heart failure self-care are thought to include the individual’s ability to manage comorbid conditions, depression or anxiety, sleep disturbances, age/developmental issues, levels of cognitive function, and health literacy (Riegel et al., 2009). But people are increasingly cognisant of the milieu of the effects of other agents.

The purpose of the analysis by Dalton (2002) is to describe the construction and initial testing of the theory of collaborative decision-making in nursing practice for a triad. The inclusion of a third person (family caregiver) in the theory required the addition of concepts about the caregiver, coalition formation, and nurse and caregiver outcomes. And other groups of patients can also helpfully inform on this debate. Patients themselves are increasingly been seen as critical ‘partners in care’. Hirsch and colleagues have outlined reasons why partners-in-care approaches are important idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, including the need to increase social capital, which deals with issues of trust and the value of social networks in linking members of a community (Hirsch et al., 2013).

I feel the answer comes not through dyads or triads, but by considering whole networks of care for the whole person. As observed elsewhere, although each professional group (e.g. nursing, neurology, physiotherapy) makes its own assessment of the needs of the patient, it appears that it is the integration of the assessment and service delivery that is perceived to be the most useful method to address the health-care needs of these patients (McCabe, Roberts and Firth, 2008). And there’s no doubt for me that this involves effective verbal and non-verbal communication all round.

Primary care visits of patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type (DAT) often involve communication among patients, family caregivers, and primary care physicians (PCPs). The objective of the study by Schmidt and colleagues was to understand the nature of each individual’s verbal participation in these triadic interactions (Schmidt, Lingler and Schulz, 2009). Caregivers of DAT patients and PCPs maintain active, coordinated verbal participation in primary care visits while patients participate less.? Interestingly, the caregivers’ verbal participation in triadic interaction was found to be also related to their reports of satisfaction with the primary care visit, specifically their satisfaction with interpersonal treatment of the patient with DAT by the PCPs. The literature is becoming, however, increasingly vigilant of the cautions in observing patient satisfaction as the outcome for a clinical consultation. In a study from Sakai and Carpenter (2011), videotapes of dementia diagnosis disclosure sessions were reviewed to examine linguistic features of 86 physician–patient–companion triads. Verbal dominance and pronoun use were measured as indications of power. Physicians dominated the conversation, speaking 83% of the total time. Evaluating patient expectations and preferences regarding physician communication style may be the most effective way of promoting patient-centered healthcare communication. To explore and gain further insight into the nature of the triadic interaction among patients, companions and physicians in first-time diagnostic disclosure encounters of Alzheimer’s disease in memory-clinic visits were studied by Karnieli and colleagues (Karnieli-Miller et al., 2012). Twenty-five real-time observations of actual triadic encounters by six different physicians were analysed, The authors found that an effective and empathic management of a triadic communication that avoids unnecessary interruptions and frustrations requires specific communication skills (e.g., explaining the rules and order of the conversation).

This is why feel two’s company, and three’s a very good thing, for English dementia policy. But I feel that wider networks at large are going to be proved to be important for whole person care, though some agents may possibly be more significant than others.

References

Adelman, R.D., Greene, M.G., Charon, R. (1987) The physician–elderly patient–companion triad in the medical encounter: the development of a conceptual framework and research agenda, The Gerontologist, 27, pp. 729–34.

Carers Trust (2013) The Triangle of Care, Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England, Second Edition (812 KB) http://static.carers.org/files/the-triangle-of-care-carers-included-final-6748.pdf

Clayman, M.L., Roter, D., Wissow, L.S., Bandeen-Roche, K. (2005) Autonomy-related behaviors of patient companions and their effect on decision-making activity in geriatric primary care visits, Soc Sci Med, 60, pp. 1583–91.

Dalton, J.M. (2003) Development and testing of the theory of collaborative decision making in nursing practice for triads, J Adv Nurs, Jan, 41(1), pp. 22-33.

De Civita M, Dobkin PL. Pediatric adherence as a multidimensional and dynamic construct, involving a triadic partnership. Pediatr Psychol. 2004 Apr May;29(3):157-69.

Greene, M.G., Majerovitz, S.D., Adelman, R.D., Rizzo, C. (1994) The effects of the presence of a third person on the physician–older patient medical interview, J Am Geriatr Soc, 42, pp. 413–9.

Hirsch, M.A., Sanjak, M., Englert, D., Iyer, S., Quinlan, M.M. (2014) Parkinson patients as partners in care. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014 Jan;20 Suppl 1:S174-9.

Hubbard, G., Illingworth, N., Rowa-Dewar, N., Forbat, L., Kearney, N. (2010) Treatment decision-making in cancer care: the role of the carer. J Clin Nurs. 2010 Jul;19(13 14):2023-31.

Karnieli-Miller, O., Werner, P., Neufeld-Kroszynski, G., Eidelman, S. (2012) Are you talking to me?! An exploration of the triadic physician-patient-companion communication within memory clinics encounters, Patient Educ Couns, Sep, 88(3), pp. 381-90.

Keady, J., Nolan, M. (2003)The dynamics of dementia: working together, working separately, or working alone? In: Nolan MR, Lundh U, Grant G, Keady J, editors. Partnerships in family care: understanding the care-giving career. Buckingham: Open University Press, p. 15–32, 2003.

McCabe, M.P., Roberts, C., Firth, L. (2008) Satisfaction with services among people with progressive neurological illnesses and their carers in Australia, Nurs Health Sci, Sept, 10(3), 209-215.

Rapoff, M. A., Lindsley, C. B., Christophersen, E. R. (1985). Parent perceptions of problems experienced by their children in complying with treatments for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 66, pp. 427–429.

Riegel, B., Moser, D.K., Anker, S.D., Appel, L.J., Dunbar, S.B., Grady, K.L., Gurvitz, M.Z., Havranek, E.P., Lee, C.S., Lindenfeld, J., Peterson, P.N., Pressler, S.J., Schocken, D.D., Whellan, D.J., American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; American Heart Association Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. (2009) State of science: promoting self care in persons with heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, Circulation, 120, pp. 1141e63.

Sakai, E.Y., Carpenter, B.D. (2011) Linguistic features of power dynamics in triadic dementia diagnostic conversations. Patient Educ Couns, Nov, 85(2), pp. 295-8.

Schmidt, K.L., Lingler, J.H., Schulz, R. (2009) Verbal communication among Alzheimer’s disease patients, their caregivers, and primary care physicians during primary care office visits, Patient Educ Couns, Nov, 77(2), pp. 197-201.

Strachan, P.H., Currie, K., Harkness, K., Spaling, M., Clark, A.M. (2014) Context matters in heart failure self-care: a qualitative systematic review, J Card Fail, Jun, 20(6), pp. 448 55.

Zaleta, A.K., Carpenter, B.D. (2010) Patient-centered communication during the disclosure of a dementia diagnosis, Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen, 25(6), pp. 513 20.

Whole person care, not misleading campaigning, will be brilliant for dementia

I believe that whole person care, to be introduced by the next Labour government, will be brilliant for bringing together health and care professionals with persons with dementia, and carers and support workers. But we should also be extremely vigilant of dodgy presentation of evidence being used ‘in the name of’ campaigning for my pet subject, dementia, I feel.

We keep on being told that the ageing population is one reason why we can no longer afford the NHS.

The clinical syndrome of dementia, for which advanced age is a risk factor, has therefore taken on a special significance in this context. Health policy gurus and politicians are seemingly having to find increasingly elaborate ways to force their agendas on an unsuspecting public. “The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism” (2007), penned by the Canadian author Naomi Klein, argues that libertarian free market policies have risen to prominence in some developed countries because of a strategy by some political leaders. These leaders deliberately exploit crises to push through controversial exploitative policies while citizens are too emotionally and physically distracted by these crises to mount an effective resistance. Crises are, though, useful instruments for bringing about change.

Within the timescale of this parliamentary term, the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge (launched in 2012) has seen a torrent of newspaper headlines with sensational memes. They invariably depict some sort of crisis in projected numbers of people with dementia, and have helped Big Pharma with the task of campaigning for increased funds to find ‘a cure for dementia’. The memes have largely had twangs of crises. For example, ‘dementia is the “next time bomb”‘ was an early news story from 7 May 2012. This messaging has continued consistently since, with the latest popular meme being “soaring numbers diagnosed with dementia“. Indeed, only recently with the arrival of the “Dementia UK (second edition) report” presented in a conference in Central London, a press release was published stating “Alzheimer’s Society calls for action as scale and cost of dementia soars”. But this messaging has caused utter confusion and resentment amongst leading academics and practitioners in dementia. The cumulative effect, instead, of such headlines and articles in public health has been to produce a feeling of ‘moral panic‘. As rightly pointed out by Dr Martin Brunet in “Pulse Magazine”, a well respected commentator on dementia policy in English primary care, recent evidence suggests rather that that the prevalence of dementia in over 65s in 2011 is lower than would have been expected. This “CFAS-II study” from Cambridge, which was published last year in the Lancet, is widely quoted, comprehensively peer-reviewed, and is extremely well known amongst people working in this field.

This is all incredibly self-defeating, as the “Prime Minister Dementia Challenge” was intended to bring greater awareness of the dementias amongst the general public not least to tackle the stigma faced by people living with dementia in their everyday lives. But you have to wonder what the intention of this approach is in the long term? The final report from the Commission on the Future of Health and Social Care in England (“Barker Commission”) was published on 4 September 2014. It discusses “the need for a new settlement for health and social care to provide a simpler pathway through the current maze of entitlements”. Labour intends to introduce ‘whole person care’ in the next parliamentary term, and it could be that this “scorched earth” approach for dementia has served a useful function. “Whole person care” is their new “big idea“. The Barker Commission recommends moving to a single, ring-fenced budget for the NHS and social care, with a single commissioner for local services.

On page 9 of their final report, the ‘ultimate star prize’ is described, the personal budget:

“Personal budgets, and care in hospital and out of it, would be provided from a single, ring-fenced budget. There would be one budget and one commissioner for individuals and their families to deal with, in place of health, social care and, in the case of those aged over 65, the Department for Work and Pensions. Commissioners would be freed to acquire care designed around an individual’s need for support and health care, largely dissolving the current definitions of what is a health need and what is a care requirement.”

And this of course is nothing new: it has been in gestation for quite some time. I myself, in fact, wrote about personal budgets for ‘Our NHS’ in my piece ‘Shop til you drop?’ on 4 September 2013. It is said that Andy Burnham MP, Shadow State of Secretary of Health, “welcomes the Barker Commission“, but one wonders whether he wishes openly to support the more unsavoury parts. Labour is desperately keen to introduce its policy changes on integrated care, without them being seen as another “top down reorganisation”. Any public resistance to their flagship policy will be political dynamite. Labour is instead currently campaigning on an anti-marketisation and anti-privatisation slate, and has pledged to repeal the highly toxic Health and Social Care Act (2012) (“the Act”).

One significant part of this repeal will be the abolition of “section 75″ and its associated regulations, which introduced competitive tendering in commissioning as the default option for NHS procurement. Nevertheless significant faultines in policy, described elegantly by Prof Calum Paton in his pamphlet “At what cost? Paying the price for the market in the English NHS” for the Centre for Health and Policy Interest (February 2013), still exist. They also are at danger of persisting, even if Labour triumphantly repeals the Act. There is a danger that unless these other pro-marketisation strands are addressed first, such as the purchaser-provider split, the “whole person care” policy will become engulfed in an intensely neoliberal direction. The counterfoil to this from Labour would presumably be that whole person care does not require a market in the first place. For this, clearly, Labour must not inflict personal budgets. A further big concern of mine is simple: not only will current scientific research into dementia have been completely misrepresented in the popular press, but also the field of dementia will be used to provide the raison d’être for yet another upheaval in service change.

And that upheaval could witness yet another change from the founding principles of the NHS. It could also be one too many.

Jeremy Hunt’s final speech to the Conservative Party conference on the NHS

This is the text of the speech given by Mr Jeremy Hunt, the Minister who oversees the running of the NHS and care despite having no legal statutory duty for it.

Today I am here to tell the British people that a future Conservative government will have no greater priority than to protect, support and invest in our NHS.

In 1948, the greatest of all Conservatives Winston Churchill supported the then Labour government in its plan to set up a National Health Service. He said ‘disease must be attacked whether it occurs in the poorest or richest man or woman simply on the grounds that it is the enemy.’

That safety net Churchill wanted is our NHS today, supported across the political spectrum.

Last week Labour tried to paint a different picture. They know this government increased the NHS budget despite the financial mess Labour left behind. They know the NHS has more doctors and more nurses than ever before. They know fewer people than ever are waiting long periods for their operations. They know the culture is becoming more caring. But they still seek to trick the public into thinking one party cares for the NHS and the other doesn’t.

Well I have a message for Mr Miliband. It’s not a Labour Health Service or a Conservative Health Service…it is a National Health Service. And when my father was cared for by a district nurse or my wife had our baby this summer or our son goes for his jabs, they aren’t Conservative patients, Labour patients or LibDem patients, they’re NHS patients. When people in this hall volunteer to support the local league of friends or join the board of a hospital we’re not Conservative supporters – we’re NHS supporters. We all support the NHS because the NHS is there for us all.

So don’t turn the National Health Service into a National Political Football and don’t use the NHS to divide us when it’s the fabric that unites our nation.

This morning the Prime Minister announced plans to make it easier for millions of people to get 8 till 8 and weekend appointments with their GPs.

And I want to start today by celebrating that and some of the other successes of our NHS, doing so well despite huge pressure.

Take cancer, our biggest killer. Every family in the country has lost a friend or loved-one to cancer – I lost my own father last year. It is a ruthlessly indiscriminate killer – whether it targets someone who has just retired after a life of hard work or a child with a life stretching out in front of them.

In 2010 this country had amongst the lowest cancer survival rates in Western Europe. So we set up the cancer drugs fund. We’ve transformed cancer diagnosis so the NHS now tests 1000 more people for cancer every single day. And so far this parliament we have treated nearly three quarters of a million more people for cancer than the last one – that’s thousands of lives saved, thousands of families kept together, thousands of tragedies averted. So let’s hear it for our brilliant cancer doctors and nurses.

Or look at dementia, one of the most terrifying conditions of all.

I’ll never forget the courage of man I met with dementia who single handedly stood up to the banks and demanded they gave him an alternative to having to remember a pin number. But it isn’t just your pin number that goes. It’s precious family memories, marriages of many years, relationships with children – all snatched away by cruel tricks of the mind. When we came to office fewer than half of those with dementia got a diagnosis, meaning many missed out on vital medicine or support for their family. We’ve now diagnosed an extra 80,000 people. The Prime Minister hosted a G8 summit to get the drug companies to do more to find a cure. And we’re working with the Alzheimers Society to enroll one million dementia friends to tackle stigma – with half a million signed up so far.

So let’s hear it for GPs, dementia nurses, dementia carers, dementia friends and people with dementia who are changing the way our society tackles this horrible condition.

Or A & E, the critical frontline for the NHS. A young A & E doctor told me how she had cried after seeing a 90 year old man say his goodbyes to a 90 year old woman he’d been married to for over 60 years. For her that was just part of the job. And with a million more people using A & E, the pressures on her and her colleagues are immense.

Sometimes, yes, it’s been tough meeting the target. But despite that we have halved the time people wait to be assessed and are treating nearly 2,000 more people every day within the four hour target compared to 2010. So let’s hear it for our brilliant A & E frontline staff now preparing for a challenging winter.

Conference our opponents say the NHS is in decline. But according to the independent Commonwealth Fund under this government the NHS became the top-rated healthcare system in the world. Better than America, better than France, better than Germany, better than Australia. And the way they rose to the challenge of Ebola says it all – with 164 NHS volunteers offering to go and help contain the outbreak in West Africa. So let’s hear it for all NHS doctors, nurses, porters, cleaners, caterers, carers and volunteers. You are the best of British and the pride of our nation.

But that doesn’t mean things are perfect. About the first thing I did as Health Secretary was to read the original Francis report about the terrible things that happened at Mid Staffs Hospital between 2005 and 2009. I was utterly horrified. As Francis made clear, system-wide failings meant these problems weren’t limited to one hospital.

One member of the public wrote to me about what happened somewhere else in a letter that was so shocking I asked to meet her.

She said she visited her late husband in hospital at 5 in the morning and found him naked on a deflated mattress, caked in urine and excrement, and curled in a foetal position with a cold air conditioner blowing directly onto his body. She still has nightmares about that visit. Now that story, thankfully, is far from typical of our NHS.

But I vowed that day that if I did nothing else, I would make sure I returned a culture of compassionate care to every corner of our NHS. Because caring is what the NHS stands for, what every doctor and nurse passionately wants, why the NHS was set up – and what a quagmire of targets, goals and plans too often allowed to be squashed.

Supported by a wonderfully committed ministerial team – Freddie Howe, Norman Lamb, Dan Poulter, Jane Ellison and George Freeman – we’re changing things.

We introduced a tough new inspection regime.

Since then our hospitals have hired over 5,000 more nurses to tackle the scandal of short-staffed wards; 5 hospitals – Basildon, North Lincs, George Eliot, Bucks and East Lancashire – have been put into special measures and been turned round; and patients are saying that they are treated with dignity and respect not just at Mid Staffs but across the NHS the highest numbers ever recorded.

Indeed on Friday of last week the CQC announced the first hospital in the country to get an ‘outstanding’ rating, Frimley Park in Camberley. Chief Executive Andrew Morris is so committed he has been there for 25 years and his son even works there as a porter. Well done to Frimley Park.

Now the problems of poor care highlighted by Robert Francis happened under Labour – so I thought Labour would rush to support me in sorting them out. In fact they did the opposite. They said talking about poor care was ‘running down the NHS.’ They even tried to vote down the law setting up a new Chief Inspector of Hospitals.

I’ll tell you what ‘running down the NHS’ is:

- It’s not learning the lessons when a mother is forced to give birth on a toilet seat, as happened in 2007. Ignored by Labour, being sorted out by us.

- It’s making hospitals Foundation Trusts even when their mortality rates are too high. Brushed aside by Labour, being sorted out by us.

- It’s stopping the CQC telling the truth about blood-stained floors in one hospital. Happened under Labour, stopped by us.

It happened in England before and it’s happening in Labour-run Wales today – so don’t you dare talk to us about running down the NHS.

Because for Labour good headlines about the NHS matter more than bad care for patients – and in our NHS nothing matters more than patients and whilst I am running it nothing ever will.

I simply say this to a Labour Party that still refuses to learn the lessons of Mid Staffs, until you do, you are not fit to run our NHS. And if you won’t put patients first we will – and it will be the Conservative Party that completes Nye Bevan’s vision for an NHS that treats every patient with dignity and respect. We will finish the job.

I could go on with my concerns about the culture Labour left behind in our NHS. But I want to look forward and deal with one of the biggest concerns people have about the NHS which is about funding.

Labour talked about putting in more money last week. But securing the NHS budget isn’t about an extra billion here or there. It’s about funding over £100bn, which is what we spend on the NHS every year. And that needs a strong economy. Because it’s very simple: you can’t fund the NHS if you bankrupt the economy. This parliament we’ve actually increased spending on the NHS by more – in real terms – than Labour promised last week. We’ve done it because of David Cameron’s personal commitment to the NHS and difficult decisions taken by George Osborne.

Other countries followed Labour’s advice. They ducked those decisions. They had no plan – and ended up cutting their health budgets. Italy by 3%, Greece by 14%, Portugal by 17%. I don’t want that to happen here.

So never forget we’ve just had the greatest squeeze on finances in NHS history because a Labour government lost control of our national finances. So to anyone worried about investment in the NHS I say this: a Labour government with reckless economic policies is the biggest single danger to funding our NHS. Do not take that risk. Nor should we forget that every penny of NHS funding comes not from the government but out of the pockets of hard working taxpayers. So if we increase spending on the NHS we must also look every one of them in the eye and promise that every penny is being spent wisely. Which means we mustn’t stop new ideas that come from outside the NHS – whether from charities or, yes, the independent sector.

Labour call this privatisation. But using a charity like WhizzKids to supply wheelchairs to disabled children or using Specsavers to speed up the supply of glasses is not privatisation. When the last Labour government used the independent sector to bring down waiting times that wasn’t privatisation either. So stop scaremongering about privatisation that isn’t happening. It nearly cost us Scotland – and we won’t let it poison the debate in England as well. Secure NHS funding backed by a strong economy is the foundation.

But the building blocks to a modern health service are two things that need real cultural change.

Personal care – a real challenge as patients navigate one of the biggest organisations in the world. And personal control – in a world which has too often said the doctor, not the patient, knows best.

I remember when I did a shift in an A & E last year. A 90 year old lady with dementia was brought in by ambulance after a fall in her care home. She was completely motionless. She couldn’t talk. She couldn’t feed herself or even drink a glass of water. What made it worse was that in that A & E we knew next to nothing about her. We didn’t have her medical record. We didn’t know her allergies. We didn’t know if she was normally able to talk or whether it was just because of the fall. To us at that hospital she was not just unknown. She was anonymous. How could we possibly give her the personal care she desperately needed?

The same could happen to any one of half a million over 90s in our society. And it could happen to anyone with long term or mental health conditions, anyone of whom can find themselves anonymously pushed from pillar to post in a system that doesn’t know who they are. But for me the point of the NHS is to make sure all everyone gets truly personal care from people who know about them, know about their condition, know about their care plan – so that what happened in that A & E never happens again.

As a first step that needs the integration of the health and social care systems. And for the first time ever this year it is happening. 150 local authority areas working together with their local NHS on their Better Care plans to pool commissioning, reduce emergency admissions and share medical records all starting from next April – with many of you in this hall involved.

But truly personal care means more than joining up health and social care. It means personal, responsive care from your GP too.

Last year I manned the phones in a busy London GP practice. The doctors there worked very hard. But what was frustrating was having to tell nearly every caller there were no appointments available for two to three weeks.

We urgently need to make it easier for busy, working people to get an appointment. That means more GPs, so I can today confirm plans to train and retain an extra 5,000 GPs.

But it also means new ways of working. Last year we announced plans for 7.5 million patients to get weekend and 8 till 8 appointments. Today we have also announced we are rolling that out to millions more – meaning this service will be available for a quarter of the whole population. And going even further, I commit that at the end of the next parliament a Conservative government will make sure every NHS patient across the whole country will be able to get weekend and 8 till 8 GP appointments.

But personal care isn’t just about a convenient appointment. It means talking to a doctor who knows about you and your condition.

Astonishingly in 2004 Labour abolished the requirement for every patient to have their own, named, personal GP. At a stroke, many patients were told they no longer had their own GP, but were merely attached to a surgery. And GPs were told they were no longer personally responsible for patients. If you have a chronic condition or complex needs, continuity of care is absolutely vital. You don’t want to have to explain everything about yourself over and over again – and you want a doctor who takes ongoing responsibility for sorting things out – not just that day but every day.

So last year I changed that back for over 75s by insisting they get a GP named on their medical record and responsible for their care. Today I can go further and announce that in the new GP contract for 2015 every single person in England will go back to having a family doctor named on their record and responsible for their care.

Personal care for every NHS patient – delivered by this government. People want personal care. But in the 21st century they want something else. Not just personal care but personal control. People with diabetes, or a heart condition, or recovering from a stroke say the best person to take control of your care is not actually your doctor – it’s you. And right now we make that far too hard. We don’t give people enough information.

So this summer we became the first country in the world to publish detailed information about safety, waiting times, patient experience and food for every major hospital. And on the new MyNHS website we’ll go further.

But it isn’t just information about your local hospital you want, it’s information about you. So today I can confirm that by April next year, every patient in England will be able to access their own medical record online – the first country in the world to take this huge step. It means you will no longer have to pay to access your medical record. You’ll be able to see it and show it to anyone you choose. You’ll find it easier to do detailed research about your condition and easier to challenge decisions. Because the boss is not the doctor – it’s you. Nothing about me without me. Personal control of your health delivered by this government.

Conference my vision is simple. We in this party have always believed passionately we should honour our debt to previous generations. So I want Britain to be the best country in the world to grow old in. I want us to enjoy the fruits of prosperity, yes, but never forget the people before us who’ve worked hard to make that possible. Never forget that all our success, all our strength, all our wealth as a country is but a hollow dream if at the end of it we are not able to give all our citizens the healthcare and support they need in old age. Never forget that it’s not a choice between a strong economy or a strong NHS. You need both and only one party – this party – can deliver both. A strong NHS. A strong economy. From a Conservative party proudly rebuilding a strong country. Personal care. Personal control. For patients treated with dignity, compassion and respect. Delivered by our party. For our NHS. For our country.

Thank you.