Living Well with Dementia: The Importance of the Person and the Environment for Wellbeing

The publication date is 17 January 2014, i.e. next week.

Thank to Charmaine Hardy (@charbhardy), a very important #dementiachallenger, for kind permission for me to use the picture of her poppy on the front cover of my book.

From the book:

“There are approximately 800,000 people with dementia in the United Kingdom, costing the economy £23bn a year. By 2040, the number of people affected is expected to double – and the costs are likely to treble.

This unique guide provides a much needed overview of dementia care. With a strong focus on the importance of patients and families, it explores the multifaceted meaning behind patient wellbeing and its vital significance in the context of national policy.

Adopting a positive, evidence-based approach, the book dispels the bleak outlook on dementia management. Its person-centred ideology considers fundamental areas such as independence, leisure and other activities, and end-of-life care – integrating the NICE quality standard where relevant. It also places great emphasis on patient environment including practical home and ward design, the importance of gardens, and sensory considerations.

All public and health care professionals will be stimulated by Rahman’s outstanding assimilation of theory and practice. Patients, their families and friends will also find much for inspiration and practical assistance.”

Benefits

- CPD accredited: helping you to achieve your points effectively for revalidation

- An evidence-based, thought-provoking overview of the ever-enlarging field of ‘living well with dementia’

- Highly practical and unique – assimilating theory and patient –centered practice. Covers topics such as communication and living well with dementia, home and ward design, assisted technology, and built environments successfully preparing readers for real-life caring

- Fully referenced with case studies, tables and charts help to illustrate key points and ensure a strong foundation of knowledge is gained.

Summary of contents

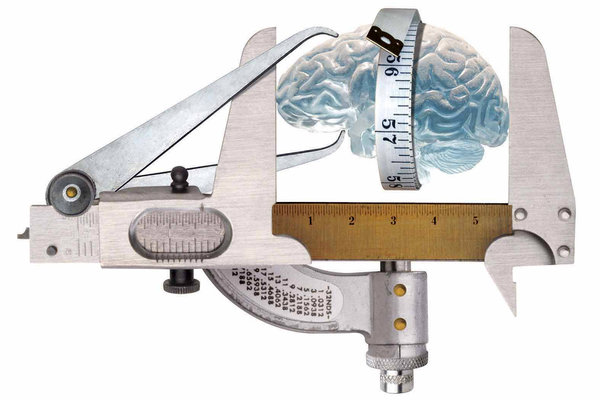

Dedication • Acknowledgements • Foreword by Professor John Hodges • Foreword by Sally Ann Marciano • Foreword by Professor Facundo Manes • Introduction • What is ‘living well with dementia’? • Measuring living well with dementia • Socio-economic arguments for promoting living well with dementia • A public health perspective on living well in dementia, and the debate over screening • The relevance of the person for living well with dementia • Leisure activities and living well with dementia • Maintaining wellbeing in end-of-life care for living well with dementia • Living well with specific types of dementia: a cognitive neurology perspective • General activities which encourage wellbeing • Decision-making, capacity and advocacy in living well with dementia • Communication and living well with dementia • Home and ward design to promote living well with dementia • Assistive technology and living well with dementia • Innovations i living well with dementia • The importance of built environments for living well with dementia • Dementia-friendly communities and living well with dementia • Conclusion

Reviews

‘Amazing … A truly unique and multi-faceted contribution. The whole book is infused with passion and the desire to make a difference to those living with dementia…A fantastic resource and user guide covering topics such as communication and living well with dementia, home and ward design, assisted technology, and built environments. Shibley should be congratulated for this unique synthesis of ideas and practice.’

Professor John R Hodges, in his Foreword

‘Outstanding…I am so excited about Shibley’s book. It is written in a language that is easy to read, and the book will appeal to a wide readership. He has tackled many of the big topics ‘head on’, and put the person living with dementia and their families at the centre of his writing. You can tell this book is written by someone who ‘understands’ dementia; someone who has seen its joy, but also felt the pain…Everyone should be allowed to live well with dementia for however long that may be, and, with this book, we can go some way to making this a reality for all.’

Sally-Ann Marciano, in her Foreword

Bringing back memories to allow people to live better with dementia

There’s been a lot of snobbery about some therapies to improve wellbeing in dementia. This snobbery I think comes in part from the idea held by some, particularly non-molecular biologists, that just because it doesn’t involve a PCR gel or test tubes, research can’t be any good.

But I’ve never been failed to be struck about how actual persons with dementia have clearly been described substantial benefit in their quality of life, with not a Big Pharma product in site.

In a 2009 study from the University of California, the human brain was imaged while people listened to music. That study found specific brain regions linked to autobiographical memories and emotions are activated by familiar music. The UC Davis study titled, “The Neural Architecture of Music-Evoked Autobiographical Memories,” was published in the journal Cerebral Cortex. That particular finding may help to explain why music can elicit strong responses from people with Alzheimer’s disease. The distributed neuronal network that the music activated is located in the medial prefrontal cortex region—right behind the forehead—and happens to be one of the last areas of the brain to atrophy over the course of Alzheimer’s disease.

In a 2011 study, on a completely different continent, Finnish researchers used a groundbreaking method that allowed them to study how the brain processes different aspects of music, such as rhythm, tonality and timbre (sound colour) in a realistic listening situation. Their study was published in the journal NeuroImage. The researchers discovered that listening to music activates wide networks in the brain, including areas responsible for motor actions, emotions, and creativity. Their method of mapping revealed complex dynamics of brain networks and the way music affects us. For this study participants were scanned with functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) while listening to a stimulus with a rich musical structure, a modern Argentinian tango.

Taken together, these findings suggest as if familiar music serves as a soundtrack for a mental movie that starts playing in our head. It calls back memories of a particular person or place, and you might all of a sudden see that person’s face in your mind’s eye. This might explain the phenomenon that some carers have noticed – that some people with dementia can start smiling when they hear a piece of music of particular significance to him or her.

And indeed the issue about how music can bring back memories is certainly alive and well.

See, for example, this recent tweet:

Harry O’Donnell, a former Clyde welder and waterpolo player, has a type of dementia known as “vascular dementia”. After a period of illness, Harry and his wife Margaret were struggling to connect with each other. “Playlist for Life” worked with them both to identify a playlist that would evoke memories from Harry’s life. Margaret began sharing it with him on an iPod at every visit.

“Playlist for Life” encourages families and caregivers to create for their loved one – at home or in residential care – a playlist of uniquely meaningful music delivered on an iPod whenever needed.

(The original source of this video is here).

There is accumulating evidence that if people with dementia are offered frequent access to the music in which their past experience and memories are embedded, it can improve their present mood, their awareness, their ability to understand and think and their sense of identity and independence. This strikingly is no matter how far their dementia has progressed. It might be also that music that is merely familiar in a general way, although pleasurable, is not likely to be so effective.

This is an example of a wider body of work known as “reminiscence therapy”. Reminiscence therapy stimulates memory and conversation through the use of prompts –images, sounds, textures, tastes, and objects that spark the senses. Research shows that it can improves mood and quality of life. Reminiscence therapy typically uses prompts, such as photos, music or familiar items from the past, to encourage the person to talk about earlier memories. Since the late 1990s, partially controlled studies have shown that this treatment has a small but significant positive effect on mood, self-care, the ability to communicate and well-being. In some cases, this therapy improves intellectual functioning.

Steve Rotheram MP referred to “The House of Memories” in the parliamentary debate on dementia care and services in Parliament this Tuesday:

“I thank the Minister for giving way. He is absolutely right about the individual care package that somebody who, unfortunately, has dementia or Alzheimer’s gets. Thankfully, long gone are the days when somebody was given a couple of tablets in the hope that that might somehow affect their condition. Is he aware of the House of Memories project in Liverpool? Is he also aware that there is an event that I am hosting here on 17 June that Members of this House are welcome to attend?”

The “House of Memories” programme demonstrates how a museum (or by association a library, arts centre, or theatre) can provide the health and social care sector with practical skills and knowledge to facilitate access to an untapped cultural resources; often within their locality. It is centered on the fantastic objects, archives and stories at the Museum of Liverpool and is delivered in partnership with a training provider, AFTA Thought. The programme provides social care staff, in domicile and residential settings, with the skills and resources they need to inform their practice and support people living with dementia.

This powerful initiative aims to raise awareness of the condition, and enable participating professional health services, carers and families to help those directly affected to live well with dementia. Indeed “House of Memories” has had a profound impact in relation to the ‘culture of care’ across the three regions, which can be directly attributed to the strong empathic qualities and personal resonance inherent in the programme’s content, design and delivery. The evaluation has revealed a demonstrable shift in participants’ cognitive and emotional understanding of dementia and its implications for those directly affected and carers alike.

Their training programme is designed to be easy to use and informative, acknowledging the central role the carer can play. They can help unlock the memory that is waiting to be shared, and provide a stimulating and rewarding experience for the person living with dementia. The programme provides participants (care workers, dementia champions, home care workers, agency support workers) with a variety of accessible practical experiences to introduce basic knowledge about the various forms of dementia, and to introduce memory activity resources linked to the museum experience, which can also be used within care settings.

To extend the learning beyond the initial training experience, participants are also equipped with resources to take back into settings. These include a ‘memory box’, a ‘suitcase of memories’, and a ‘memory toolkit’.

The power of memories in general life is undeniable. “Nothing is ever really lost to us as long as we remember it”, as L.M. Montgomery said in “The Story Girl”.

Thanks to @TommyNTour [Thomas Whitelaw] for sharing “Playlist for life”.

Can you ‘nudge’ your way out of ‘fixed odds betting’?

Left to its own devices, can the unfettered market be good for your health?

The period of office for the coalition so far, neoliberal in flavour, has seen a number of examples where various industries have found, it is alleged, a sympathetic ear from the Conservative and Liberal Democrats in government. But the question is: are these parties now making a difference to your health, to its detriment?

Not long after the start of the discussion of standard cigarette packaging, and amidst of continuing talk of concerns of the level of sugar in processed foods, politicians and the media have turned to ‘fixed odds betting terminals’. Many see the ’24 hour drinking culture’, a policy plank of a previous New Labour administration, to have been left a largely negative longstanding legacy with some vulnerable individuals.

The ‘cost of living crisis’ is a very clever way for Ed Miliband to introduce a much wider issue. Far from the market being liberalising, the market is in fact producing unreasonable fetters on us, it is argued. Neoliberal proponents do not obviously wish to tout the notion that a free market is in fact bad for your health.

Fixed odds betting terminals were launched in 1999, after then chancellor Gordon Brown scrapped tax on individual bets in favour of taxing bookmakers’ profits. It depends of course where you draw the line with these ‘pleasurable activities’. Drinking socially is an altogether different phenomenon to drinking a bottle of vodka for breakfast to overcome withdrawal symptoms. Just as drinking is legal, some forms of betting are legal, and all Governments have taxed them. The traditional argument is that this tax revenue can contribute to funding health and social care services, including ‘new innovative’ ways of treating addiction.

High stakes casino-style gambling was banned from High Streets, but fixed odds betting terminals used remote servers so that the gaming was not taking place on the premises. After the Gambling Act [2005], fixed odds betting terminals were given legal backing, and put under the same regulatory framework as fruit machines. They stopped using remote servers but stakes were limited to £100 and terminals to four per betting shop. Punters could place a £100 stake every 20 seconds. According to the Gambling Commission there are 33,284 fixed-odds betting terminals across the UK. The number of betting shops in the UK has increased from 8,500 to 9,100 over the past two years, with hundreds more planned. Unlike traditional fruit machines in pubs and amusement arcades, punters can gamble up to £100 every 20 seconds on fixed odds betting terminals, attracted by payouts of up to £500.

It is said that most people gamble at some point in their lives, but for some gambling can become a serious addiction. For the vast majority of people, gambling entails putting a bet on a sports match now and again or entering the weekly lottery draw. However, for a small proportion of gamblers, betting and playing games to win money can become a serious addiction, which can spiral out of control and affect their professional and social lives. In the UK, it is estimated that around 350,000 people are suffering from a gambling addiction. In recent years, the number of people experiencing problems with gambling has increased due to economic troubles associated with the global recession and an increase in the number of gambling outlets, it is thought.

There are some hints if you end up answering ‘yes’ to any of these questions: Do you take time off work to gamble? Are you in debt? Do you prioritise gambling over your family/friends/work/hobbies? Do you lie to others about your financial situation? Do you think about gambling a lot? Does your loved one become defensive or embarrassed when you ask them about gambling? Do they make excuses or lie about where they have been or how much money they have spent? Are they becoming increasingly secretive about money? Do they hide bank statements or leave them unopened? Ultimately, people who’ve fallen victim to a ‘fixed odds betting addiction’ will demonstrate the cardinal features of all addictive behaviours: tolerance to getting the ‘high’, and the need to avoid bad withdrawal symptoms from continued problem addictive behaviour.

Conversely, the “nudge” or, more formally, libertarian paternalist approach has been high on the political agenda during the period of the currrent Government. The reason for the political popularity of nudging is that offers politicians a tool by which they can offer guidance, without enforcement, on individual behaviour change that is good for and, on reflection, preferred by, individuals themselves. Various nudge policies have been proposed to tackle obesity, and it is useful perhaps to consider why or how these have not worked well either.

Whilst there are few overt ‘physical’ symptoms or signs compared to other addictions (such as weight/addiction to food, cirrhosis/addiction to alcohol), you can easily piece together an explanation for why all is not quite ‘normal’ with the human body. In 1998, Koepp and colleagues published a very famous paper in Nature (May 21;393(6682):266-8) arguing evidence for “striatal dopamine release during a video game.” Signalling in the brain and brainstem using the chemical ‘dopmaine’ may be involved in learning, reinforcement of behaviour, attention, and sensorimotor integration. The authors found evidence that endogenous dopamine is released in the human striatum during a goal-directed motor task, namely a video game.

A “pleasure centre” was discovered in the 1950s by two brain researchers named James Olds and Peter Milner who were investigating whether rats might be made uncomfortable by electrical stimulation of certain areas of their brain. In this work and work arising from this, the “nucleus accumbens” (NAcc) was found to be linked to the rewarding of human behaviours. The human brain and the cluster of NAcc brain cells partner together to provide these clues by releasing chemicals. The two main chemicals that are released into the NAcc upon certain stimulation are dopamine and serotonin. Dopamine is the neurotransmitter that increases the desire for that stimulant. Stimulants have been found to include sex and drugs of addiction as ‘reinforcers’, and money can be viewed as a ‘higher order reinforcer’ as money in theory can buy you sex or drugs or addiction for example.

In a Commons debate in which Labour demanded tougher curbs on high street “mini-casinos”, ministers promised measures to protect gamblers later this year after a Government review. The pledge came as the Government comfortably defeated a Labour motion calling for councils to be given power to limit the number of high-stake fruit machines by 314 to 232, a majority of 82. Despite the large Government majority, some Tory MPs backed calls for urgent action and a small number of Coalition back benchers are thought to have abstained. In a Commons vote last month, four Tory MPs voted against the Government and supported Labour in its calls for the stakes on the so-called fixed odds betting terminals to be slashed from £100 to £2.

For decades, the neoliberal protagonists have derided the law and regulation as ‘adding red tape’, obstructing the market. Nonetheless, legislative statutory instruments have made it to the statute books, such as regulation for air quality. In the same way that there is perhaps ‘responsible capitalism’ (though there are some who reject capitalism altogether so find the idea of responsible capitalism predictably an oxymoron), there is perhaps growing acceptance that the State can intervene in protecting its citizens. This is after all what Ed Miliband and Labour is attempting to do with energy bills, for example. You can choose to approach gambling addictions in much the same way as other addictions are managed psychologically (for example through the ’12 steps program’ with individuals admitting first “powerlessness” over their gambling behaviours). There are other valid approaches too. Or you can tackle fixed odds betting, and the causes of fixed odds betting.

Personal budgets and dementia

Currently in England, according to the Government, more than 15 million people have a long term condition – a health problem that can’t be cured but can be controlled by medication or other therapies. This figure is set to increase over the next 10 years, particularly those people with 3 or more conditions at once. Examples of long term conditions include high blood pressure, depression, and arthritis. Of course, a big one is dementia, an “umbrella term” which covers hundreds of different conditions. There are 800,000 people in the United Kingdom who are thought to have one of the dementias. However, a thrust of national policy has been directed at trying to remedy the diagnosis rate which had been perceived as poor (from around 40%).

The Mental Health Foundation back in 2009 had publicly set out a wish that there would be a high level of satisfaction among people living with dementia and their carers with planning and arranging the ongoing support they receive via the different forms of self-directed support, and that specific examples and stories of real experiences, both positive and negative, in the use of the different forms of self-directed support will have been shared. Indeed, various stories have been fed into the media at various points in the intervening years.

People, however, tend to underestimate the extent to which GPs cannot treat underlying conditions.

For example, a GP faced with a headache, the most common neurological presentation in primary care, might decide to treat it symptomatically, except where otherwise indicated.

A GP faced with an individual which is asthmatic may not have a clear idea about the causes of shortness of breath and wheeziness, but might reach for his or her prescription pad to open up the airways with a ‘bronchodilator’ such as salbutamol.

However, this option not only does not work effectively for memory problems in early Alzheimer’s disease for many (although the cholinesterase inhibitors might have some success in early diffuse Lewy Body’s Disease). It is also very relatively expensive for the NHS compared to other more efficacious interventions, arguably. In September 2013, it was reported that treatment of mild cognitive impairment with members of a particular class of medications, called “acetylcholinesterase inhibitors” was ‘not associated with any benefit’ and instead carried with them an increased risk of side effects, according to a new analysis. The “meta-analysis” – published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal – looked at eight studies using donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine in mild cognitive impairment.

These experts argued that the findings raised questions over the Government’s drive for earlier diagnosis of dementia, but the issue is that medications may not be the only fruit for a person with dementia in the future. One aspect of ‘liberalising the NHS’, a major Coalition drive embodied in the Health and Social Care Act (2012), is that clinical commissioning groups can ‘shop around’ for whatever contracts they wish, with the default option being competitive tendering through the Regulations published for section 75. When a person receives a timely diagnosis for dementia, it’s possible that a “personal health budget” might be open to that person with dementia in future.

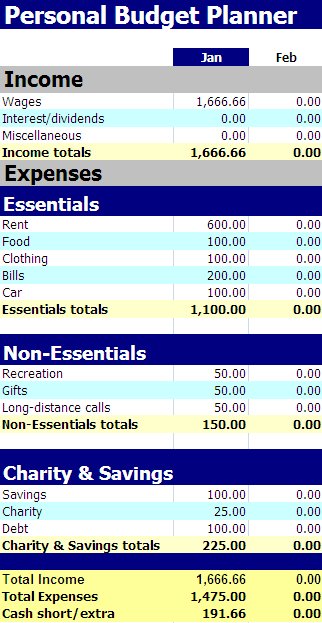

A personal budget describes the amount of money that a council decides to spend in order to meet the needs of an individual eligible for publicly funded social care. It can be taken by the eligible person as a managed option by the council or third party, as a direct (cash) payment or as a combination of these options. At their simplest level, personal budgets involve a discussion with the service user/carer about how much money has been allocated to meet their assessed care needs, how they would like to spend this allocation and recording these views in the care plan.

For some, the debate about ‘personal health budgets’ is not simply an operational matter. They are symbolic of two competing political philosophies and ideologies. A socialist system involves solidarity, cooperation and equality (not as such “equality of provider power” such as the somewhat neoliberal NHS vs ‘any qualified provider’ debate). A neoliberal one, encouraging individualised budgets, views the market in the same way that Hayek and economists from the Austrian school view the economy: as one giant information system where prices are THE metric of how much something is worth. In contrast, the “national tariff” is the health version of interest rates, artificially set by the State. Strikingly, cross-party support is lent in the implementation of this policy plank, largely without a large and frank discussion with members of the general public at election time.

A major barrier to having a coherent conversation about this is that the major protagonists promoting personal budgets tend to have a vested interest in some sort for promoting them. That is of course not to argue that they should be muzzled from contributing to the debate. But it’s quite hard to deny that personal health budgets not offer potentially more choice and control for a person with dementia (possibly with a carer as proxy), unless of course there’s “no money left” as Liam Byrne MP might put it.

With the introduction of ‘whole person care’ as Labour know it, or ‘integrated care’ as the Conservatives put it, it is likely that policy will move towards a voluntary roll-out of a system where health and social care budgets come under one unified budget. No political party wishes to be seen to compromise the founding principle of the NHS as ‘comprehensive, universal and free-at-the-point-of-need’ (it is not as such ‘free’, in that health is currently funded out of taxation), but increasingly more defined groups are being offered personal budgets. Personal health budgets could lead to a change of emphasis from expensive drugs which in the most part have little effect, say to relatively inexpensive purchases which could have massive effect to somebody’s wellbeing or quality of life. Critics argue that, by introducing a component of ‘top up payments’, and with the blurring of boundaries between health and social care with very different existant ways of doing things, that ‘whole person care’ or ‘integrated care’ could be a vehicle for delivering real-time cuts in what should be available anyway.

On Wednesday 9 October 2013, Earl Howe, Lord Hunt and Lord Warner didn’t appear to have any issue about a duty to promote wellbeing in the Care Bill, though they differ somewhat on who should promote that particular duty. This is recorded faithfully in Hansard.

Wellbeing is certainly not a policy plank which looks like disappearing in the near future. Norman Lamb, Minister for State for Care Services, explicitly referred to the promotion of wellbeing in dementia in the ‘adjournment debate’ yesterday evening:

“There is also an amendment to the Care Bill which will require that commissioning takes into account an individual’s well-being. Councils cannot commission on the basis of 15 minutes of care when important care work needs to be undertaken. They will not meet their obligation under the Care Bill if they are doing it in that.”

The broad scope of the G8 summit was emphasised by Lamb:

“The declaration and communiqué announced at the summit set out a clear commitment to working more closely together on a range of measures to improve early diagnosis, living well with dementia, and research.”

And strikingly wellbeing has not been excluded from the dementia strategy strategy at all.

This is in contradiction to what might have appeared from the peri-Summit public discussions which were led by researchers with particularly areas in neuroscience, much of which is funded by industry.

Norman Lamb commented that:

“Since 2009-10, Government-funded dementia research in England has almost doubled, from £28.2 million to £52.2 million in 2012-13. Over the same period, funding by the charitable sector has increased, from £4.2 million to £6.8 million in the case of Alzheimer’s Research UK and from £2 million to £5.3 million in the case of the Alzheimer’s Society. In July 2012, a call for research proposals received a large number of applications, the quality of which exceeded expectations. Six projects, worth a combined £20 million, will look at areas including: living well with dementia; dementia-associated visual impairment; understanding community aspects of dementia; and promoting independence and managing agitation in people with dementia.”

In quite a direct way, the issue of ‘choice and control’ offered by personal health budgets needs to be offered from parallel ‘transparency and disclosure’, in the form of valid consent, from health professionals with persons with dementia in discussing medications. With so many in power and/or influence clearly trumping up the benefits of cholinesterase inhibitors, with complex and costly Pharma-funded project looking at whether any of these drugs have a significant effect on parts of the brain and so forth, both persons and patients with dementia need to have a clear and accurate account of the risks and benefits of drugs from medical professionals who are regulated to give such an account. This is only fair if psychological (and non-pharmacological) treatments are to be subject to such scrutiny particularly by the popular press.

The personal health budgets have particular needs, and they are obvious to those with medical knowledge of these conditions. Quite often there might be a psychological reaction of denial about the condition and needs, associated the stigma and personal fear about ‘having’ dementia; but this can be coupled with a lack of insight into the manifestations of dementia, such as the insidious behavioural and personality changes which can occur early on in the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. There might also fluctuating levels of need on a day to day basis; like all of us, people with dementia have ‘good days and bad days’, but some subtypes of dementia may have particularly fluctuating time courses (such as diffuse Lewy Body Dementia). Apart from the very small number of cases of reversible or potentially treatable presentations which appear like dementia, dementia is a degenerative condition and so abilities and needs change over time. This can of course be hard to predict for anyone; the person, patient, friend, family member, carer or professional.

So having laid out the general direction of travel of ‘personal budgets’, it’s clearly important to consider the particular challenges which lie ahead. In the Alzheimer’s Society document, “Getting personal? Making personal budgets work for people with dementia” from November 2011, a survey for “Support. Stay. Save.” (2011) is described. This survey was conducted in late 2010, and comprised people with dementia and carers across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In total there were 1,432 respondents. The survey asked whether the person with dementia is using a direct payment or personal budget to buy social care services. 204 respondents said that they were using a personal budget or direct payment to purchase services and care. In total 878 respondents had been assessed and were receiving social services support, meaning that 23% of eligible respondents were using a personal budget or direct payment arrangement. Younger people with dementia and their carers appeared more likely to have been offered, and be using, direct payments or personal budgets than older people with dementia.

This is intriguing itself because the neurology of early onset dementia. Two particular diagnostic criteria are diffuse Lewy Body dementia which tends to have a ‘fluctuating’ time course in cognition to begin with, and the frontotemporal dementias where memory for events or facts (“episodic memory”) can be relatively unimpaired until the later stages. Clearly, the needs of such individuals with dementia will be different from those who have the early onset of Alzheimer’s disease, where episodic memory is more of an issue. Such differences will clearly have an effect on the types of needs of such individuals, but it can be argued that the patient himself or herself (or a proxy) will be in a better position to know what those needs might be. A person with overt problems in spatial memory, memory for where you are, might wish to have a focus on better signage in his or her own environment for example, which might be a useful non-pharmacological intervention. Such a person might prefer a telephone with pictures of closest friends and family to remind him or her of which pre-programmed functional buttons. Such a small disruptive change could potentially make a huge difference to someone’s quality of life.

As the dementias progress, nonetheless, it could be that persons with dementia benefit from assisted technologies to allow them to live independently at home wherever possible. This is of course a rather liberal approach. It is a stated aim of the current Coalition government that they want to help people to manage their own health condition as much as possible. Telehealth and telecare services are a useful way of doing this, it is argued. According to the Government, at least 3 million people with long term conditions could benefit from using telehealth and telecare. Along with the telehealth and telecare industry, they are using the 3millionlives campaign to encourage greater use of remote monitoring information and communication technology in health and social care. It is vehemently denied by the Labour Party that ‘whole person care’ would be amalgamated with ‘universal credit’, forging together the benefits and budget narratives. Apart from anything else, the implementation of universal credit under Iain Duncan-Smith has been reported as a total disaster. But there is a precedent from the Australian jurisdiction of the bringing together of the two narratives, as described by Liam Byrne and Jenny Macklin in the Guardian in September 2013. In this jurisdiction, adapting to disability can mean that your benefit award is in fact LOWER. If the two systems merged here – and this is incredibly unlikely at the moment – a person with disability and dementia in a worst case scenario could find that what they gain in the personal budget hand is being robbed to pay for the benefits hand. Interestingly, in the Australian jurisdiction, personal health budgets have an equivalent called “consumer directed care”, which is perhaps a more accurate to view the emerging situation?

There are of course issues about the changing capacity of a person with dementia as the condition progresses, and this has implications for the medical ethics issues of autonomy, consent, ‘best interests’, beneficience and non-maleficence inter alia. Working through carers can be seen a good enough proxy for working directly with the person with dementia, and of course a major policy issue is a clear need to avoid financial abuse, fraud and discrimination which can be unlawful and/or criminal under English law. However this in itself is not so simple. A person with dementia living with dementia, and his or her carer(s) should not necessarily be regarded as a ‘family unit’. Furthermore, caring professional services – both general and specialist, and health and social care – may not be signed up culturally to full integration, involving sharing of information. For example, we are only just beginning to see a situation where some care homes are at first presentation investigating the medical needs of some persons with dementia in viewing their social care (and not all physicians are fluent in asking about social care issues.) It is possible that #NHSChangeDay could bring about a change in culture, where at least NHS professionals bother asking a person with dementia about his perception and self-awareness of quality of life. This is indeed my own personal pledge for staff in the NHS for #NHSChangeDay for 2014.

I, like other stakeholders such as persons with dementia, can appreciate that the ground is shifting. I can also sense a change in direction in weather from a world where people have put all their eggs in the Pharma and biological neuroscientific basket. Of course improved symptomatic therapies, and possibly a cure, one day would be a great asset to the personal armour in the ‘war against dementia’. Of course, if this battle is won, the war to ensure that the NHS is able to provide this universally and free-at-the-point-of-need is THE war to be won, whatever the direction of ‘personal health budgets’. But I feel that the direction of personal health budgets has somewhat a degree of inevitability about it, in this jurisdiction anyway.

Thanks to @KateSwaffer for help this morning too.

Could personal budgets give better choice and control over cure or care for dementia?

“But in the final months of my mum’s life last year, our family saw both the best of the NHS and things that need to change – like a microcosm of the national strategic challenge. We saw fantastic GP support, great specialist cancer services and unbelievably supportive hospice care. We also saw insufficient community support (not enough district nursing and too few hours of home support via continuing health care). But this was not just an issue of insufficient resources in the wrong places, there were also problems related to a lack of shared decision making. My mum felt too powerless in the face of decisions made by systems that professionals felt they had to go along with and managers enacted.”

“Personal Health Budgets and the left – less heat more light please”

This article is an excellent overview of personal health budgets by Martin Routledge.

Currently in England, according to the Government, more than 15 million people have a long term condition – a health problem that can’t be cured but can be controlled by medication or other therapies. This figure is set to increase over the next 10 years, particularly those people with 3 or more conditions at once. Examples of long term conditions include high blood pressure, depression, and arthritis. Of course, a big one is dementia, an “umbrella term” which covers hundreds of different conditions. There are 800,000 people in the United Kingdom who are thought to have one of the dementias. However, a thrust of national policy has been directed at trying to remedy the diagnosis rate which had been perceived as poor (from around 40%).

The Mental Health Foundation back in 2009 had publicly set out a wish that there would be a high level of satisfaction among people living with dementia and their carers with planning and arranging the ongoing support they receive via the different forms of self-directed support, and that specific examples and stories of real experiences, both positive and negative, in the use of the different forms of self-directed support will have been shared. Indeed, various stories have been fed into the media at various points in the intervening years.

People, however, tend to underestimate the extent to which GPs cannot treat underlying conditions.

For example, a GP faced with a headache, the most common neurological presentation in primary care, might decide to treat it symptomatically, except where otherwise indicated.

A GP faced with an individual which is asthmatic may not have a clear idea about the causes of shortness of breath and wheeziness, but might reach for his or her prescription pad to open up the airways with a ‘bronchodilator’ such as salbutamol.

However, this option not only does not work effectively for memory problems in early Alzheimer’s disease for many (although the cholinesterase inhibitors might have some success in early diffuse Lewy Body’s Disease). It is also very relatively expensive for the NHS compared to other more efficacious interventions, arguably. In September 2013, it was reported that treatment of mild cognitive impairment with members of a particular class of medications, called “acetylcholinesterase inhibitors” was ‘not associated with any benefit’ and instead carried with them an increased risk of side effects, according to a new analysis. The “meta-analysis” – published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal – looked at eight studies using donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine in mild cognitive impairment.

These experts argued that the findings raised questions over the Government’s drive for earlier diagnosis of dementia, but the issue is that medications may not be the only fruit for a person with dementia in the future. One aspect of ‘liberalising the NHS’, a major Coalition drive embodied in the Health and Social Care Act (2012), is that clinical commissioning groups can ‘shop around’ for whatever contracts they wish, with the default option being competitive tendering through the Regulations published for section 75. When a person receives a timely diagnosis for dementia, it’s possible that a “personal health budget” might be open to that person with dementia in future.

A personal budget describes the amount of money that a council decides to spend in order to meet the needs of an individual eligible for publicly funded social care. It can be taken by the eligible person as a managed option by the council or third party, as a direct (cash) payment or as a combination of these options. At their simplest level, personal budgets involve a discussion with the service user/carer about how much money has been allocated to meet their assessed care needs, how they would like to spend this allocation and recording these views in the care plan. Personal budgets differ from personal health budgets, and from individualised budgets, and you can read an overview of them here.

For some, the debate about ‘personal health budgets’ is not simply an operational matter. They are symbolic of two competing political philosophies and ideologies. A socialist system involves solidarity, cooperation and equality (not as such “equality of provider power” such as the somewhat neoliberal NHS vs ‘any qualified provider’ debate). A neoliberal one, encouraging individualised budgets, views the market in the same way that Hayek and economists from the Austrian school view the economy: as one giant information system where prices are THE metric of how much something is worth. In contrast, the “national tariff” is the health version of interest rates, artificially set by the State. Strikingly, cross-party support is lent in the implementation of this policy plank, largely without a large and frank discussion with members of the general public at election time.

A major barrier to having a coherent conversation about this is that the major protagonists promoting personal budgets tend to have a vested interest in some sort for promoting them. That is of course not to argue that they should be muzzled from contributing to the debate. But it’s quite hard to deny that personal health budgets not offer potentially more choice and control for a person with dementia (possibly with a carer as proxy), unless of course there’s “no money left” as Liam Byrne MP might put it.

With the introduction of ‘whole person care’ as Labour know it, or ‘integrated care’ as the Conservatives put it, it is likely that policy will move towards a voluntary roll-out of a system where health and social care budgets come under one unified budget. No political party wishes to be seen to compromise the founding principle of the NHS as ‘comprehensive, universal and free-at-the-point-of-need’ (it is not as such ‘free’, in that health is currently funded out of taxation), but increasingly more defined groups are being offered personal budgets. Personal health budgets could lead to a change of emphasis from expensive drugs which in the most part have little effect, say to relatively inexpensive purchases which could have massive effect to somebody’s wellbeing or quality of life. Critics argue that, by introducing a component of ‘top up payments’, and with the blurring of boundaries between health and social care with very different existant ways of doing things, that ‘whole person care’ or ‘integrated care’ could be a vehicle for delivering real-time cuts in what should be available anyway.

On Wednesday 9 October 2013, Earl Howe, Lord Hunt and Lord Warner didn’t appear to have any issue about a duty to promote wellbeing in the Care Bill, though they differ somewhat on who should promote that particular duty. This is recorded faithfully in Hansard.

Wellbeing is certainly not a policy plank which looks like disappearing in the near future. Norman Lamb, Minister for State for Care Services, explicitly referred to the promotion of wellbeing in dementia in the ‘adjournment debate’ yesterday evening:

“There is also an amendment to the Care Bill which will require that commissioning takes into account an individual’s well-being. Councils cannot commission on the basis of 15 minutes of care when important care work needs to be undertaken. They will not meet their obligation under the Care Bill if they are doing it in that.”

The broad scope of the G8 summit was emphasised by Lamb:

“The declaration and communiqué announced at the summit set out a clear commitment to working more closely together on a range of measures to improve early diagnosis, living well with dementia, and research.”

And strikingly wellbeing has not been excluded from the dementia strategy strategy at all.

This is in contradiction to what might have appeared from the peri-Summit public discussions which were led by researchers with particularly areas in neuroscience, much of which is funded by industry.

Norman Lamb commented that:

“Since 2009-10, Government-funded dementia research in England has almost doubled, from £28.2 million to £52.2 million in 2012-13. Over the same period, funding by the charitable sector has increased, from £4.2 million to £6.8 million in the case of Alzheimer’s Research UK and from £2 million to £5.3 million in the case of the Alzheimer’s Society. In July 2012, a call for research proposals received a large number of applications, the quality of which exceeded expectations. Six projects, worth a combined £20 million, will look at areas including: living well with dementia; dementia-associated visual impairment; understanding community aspects of dementia; and promoting independence and managing agitation in people with dementia.”

In quite a direct way, the issue of ‘choice and control’ offered by personal health budgets needs to be offered from parallel ‘transparency and disclosure’, in the form of valid consent, from health professionals with persons with dementia in discussing medications. With so many in power and/or influence clearly trumping up the benefits of cholinesterase inhibitors, with complex and costly Pharma-funded projects looking at whether any of these drugs have a significant effect on parts of the brain and so forth, both persons and patients with dementia need to have a clear and accurate account of the risks and benefits of drugs from medical professionals who are regulated to give such an account. This is only fair if psychological (and non-pharmacological) treatments are to be subject to such scrutiny particularly by the popular press.

The personal health budgets have particular needs, and they are obvious to those with medical knowledge of these conditions. Quite often there might be a psychological reaction of denial about the condition and needs, associated the stigma and personal fear about ‘having’ dementia; but this can be coupled with a lack of insight into the manifestations of dementia, such as the insidious behavioural and personality changes which can occur early on in the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. There might also fluctuating levels of need on a day to day basis; like all of us, people with dementia have ‘good days and bad days’, but some subtypes of dementia may have particularly fluctuating time courses (such as diffuse Lewy Body Dementia). Apart from the very small number of cases of reversible or potentially treatable presentations which appear like dementia, dementia is a degenerative condition and so abilities and needs change over time. This can of course be hard to predict for anyone; the person, patient, friend, family member, carer or professional.

So having laid out the general direction of travel of ‘personal budgets’, it’s clearly important to consider the particular challenges which lie ahead. In the Alzheimer’s Society document, “Getting personal? Making personal budgets work for people with dementia” from November 2011, a survey for “Support. Stay. Save.” (2011) is described. This survey was conducted in late 2010, and comprised people with dementia and carers across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In total there were 1,432 respondents. The survey asked whether the person with dementia is using a direct payment or personal budget to buy social care services. 204 respondents said that they were using a personal budget or direct payment to purchase services and care. In total 878 respondents had been assessed and were receiving social services support, meaning that 23% of eligible respondents were using a personal budget or direct payment arrangement. Younger people with dementia and their carers appeared more likely to have been offered, and be using, direct payments or personal budgets than older people with dementia.

This is intriguing itself because the neurology of early onset dementia. Two particular diagnostic criteria are diffuse Lewy Body dementia which tends to have a ‘fluctuating’ time course in cognition to begin with, and the frontotemporal dementias where memory for events or facts (“episodic memory”) can be relatively unimpaired until the later stages. Clearly, the needs of such individuals with dementia will be different from those who have the early onset of Alzheimer’s disease, where episodic memory is more of an issue. Such differences will clearly have an effect on the types of needs of such individuals, but it can be argued that the patient himself or herself (or a proxy) will be in a better position to know what those needs might be. A person with overt problems in spatial memory, memory for where you are, might wish to have a focus on better signage in his or her own environment for example, which might be a useful non-pharmacological intervention. Such a person might prefer a telephone with pictures of closest friends and family to remind him or her of which pre-programmed functional buttons. Such a small disruptive change could potentially make a huge difference to someone’s quality of life.

As the dementias progress, nonetheless, it could be that persons with dementia benefit from assistive technologies to allow them to live independently at home wherever possible. This is of course a rather liberal approach. It is a stated aim of the current Coalition government that they want to help people to manage their own health condition as much as possible. Telehealth and telecare services are a useful way of doing this, it is argued. According to the Government, at least 3 million people with long term conditions could benefit from using telehealth and telecare. Along with the telehealth and telecare industry, they are using the 3millionlives campaign to encourage greater use of remote monitoring information and communication technology in health and social care. It is vehemently denied by the Labour Party that ‘whole person care’ would be amalgamated with ‘universal credit’, forging together the benefits and budget narratives. Apart from anything else, the implementation of universal credit under Iain Duncan-Smith has been reported as a total disaster. But there is a precedent from the Australian jurisdiction of the bringing together of the two narratives, as described by Liam Byrne and Jenny Macklin in the Guardian in September 2013. In this jurisdiction, adapting to disability can mean that your benefit award is in fact LOWER. If the two systems merged here – and this is incredibly unlikely at the moment – a person with disability and dementia in a worst case scenario could find that what they gain in the personal budget hand is being robbed to pay for the benefits hand. Interestingly, in the Australian jurisdiction, personal health budgets have an equivalent called “consumer directed care”, which is perhaps a more accurate to view the emerging situation?

There are of course issues about the changing capacity of a person with dementia as the condition progresses, and this has implications for the medical ethics issues of autonomy, consent, ‘best interests’, beneficience and non-maleficence inter alia. Working through carers can be seen a good enough proxy for working directly with the person with dementia, and of course a major policy issue is a clear need to avoid financial abuse, fraud and discrimination which can be unlawful and/or criminal under English law. However this in itself is not so simple. A person with dementia living with dementia, and his or her carer(s) should not necessarily be regarded as a ‘family unit’. Furthermore, caring professional services – both general and specialist, and health and social care – may not be signed up culturally to full integration, involving sharing of information. For example, we are only just beginning to see a situation where some care homes are at first presentation investigating the medical needs of some persons with dementia in viewing their social care (and not all physicians are fluent in asking about social care issues.) It is possible that #NHSChangeDay could bring about a change in culture, where at least NHS professionals bother asking a person with dementia about his perception and self-awareness of quality of life. This is indeed my own personal pledge for staff in the NHS for #NHSChangeDay for 2014.

I, like other stakeholders such as persons with dementia, can appreciate that the ground is shifting. I can also sense a change in direction in weather from a world where people have put all their eggs in the Pharma and biological neuroscientific basket. Of course improved symptomatic therapies, and possibly a cure, one day would be a great asset to the personal armour in the ‘war against dementia’. Of course, if this battle is won, the war to ensure that the NHS is able to provide this universally and free-at-the-point-of-need is THE war to be won, whatever the direction of ‘personal health budgets’. But I feel that the direction of personal health budgets has somewhat a degree of inevitability about it, in this jurisdiction anyway.

Thanks to @KateSwaffer for help this morning too.

Anybody who expects the Liberal Democrats to ‘save the day’ over the hospital closure clause is frankly deluding himself

Some people believe optimistically that the Liberal Democrats will suddenly have a change of heart.

The chances though of the Liberal Democrats joining Andy Burnham MP (see tweet) in the opposition lobby is about as likely as an ostrich landing on the moon.

The construct of ‘collective responsibility’ means that Liberal Democrats in Government vote with major Coalition party. It was Nick Clegg who predetermined that the Liberal Democrats would go into office with the party with the most number of seats. That was a fairly safe prediction at the time.

It’s widely predicted that irrespective of whether there is a hung parliament on the morning of May 8th 2015 that Labour will have the most number of seats. This is particularly more likely given the boundary reforms which the Conservative Party failed to achieve. That being the case, it raises the possibility of Nick Clegg being the Deputy Prime Minister, and the Liberal Democrats in office, for about a decade despite having never ‘won’ two elections.

It also raises the possibility of Liberal Democrat votes being used to repeal legislation from the lifetime of this parliament, albeit that no party can legislate to bind its successors. But the idea of the LibDems suddenly having a change of heart, to differentiate themselves as per the “differentiation strategy”, is scuppered by three prominent issues.

Firstly, the major thrust of any Government is its economic policies, and the LibDems have already indicated that they can only sign up to aggressive deficit reduction. This could be fine of course if Ed Balls offers the same meat but with slightly different gravy.

Secondly, the recent history of the Liberal Democrats is more than clear. They have got rid of the “social” bit in “The Social and Liberal Democrat Party”. Nick Clegg, having trained under Leon Brittan in the EU, has a competitive neoliberal philosophy, and he mixes in the company with people who share his zest for that sort of thing. Like David Laws. He would with Chris Huhne. A neoliberal firestorm in closing hospitals down due to failure régimes, of the type seen to by clause 118 is entirely in keeping with this neoliberal philosophy, not a social democrat one based on local democratic power.

Thirdly, there is no basis for believing that the Liberal Democrats will suddenly ‘come good’ as the term of this parliament comes to an end.

On 20th March 2012, the Commons voted the Health and Social Care Bill through at 10.15pm, spending less than 6 hours debating the 357 amendments made in the Lords. The Labour motion on disclosure of the risk register was lost by 328 to 246 votes. Two LibDems voted with Labour, Greg Mulholland and Adrian Sanders and three abstained. Most of the Lords amendments passed and the government won most by about 80-90 votes as the bulk of the Lib Dems voted with the government. The unpopular Health and Social Care Act came into law under this Government, though.

Also, despite near universal professional opposition and strong political pressure, the Section 75 regulations that explicitly open up the NHS to competition law were approved in the House of Lords A three-line whip on Liberal Democrat peers ensured a majority of over a hundred, with Baroness Shirley Williams speaking warmly of “an exciting new direction” for the NHS. This is the same Baroness Williams whom Tony Benn alleges in his diaries wished to tax benefits in the Callaghan government of the 1970s. The unpopular Section 75 Regulations came into law under this Government, though.

In January 2012, the government fought off a fresh challenge to its controversial welfare reform bill, when peers rejected a proposal to delay the full introduction of slashed new disability payments after ministers offered concessions. The unpopular Welfare Reform Act came into law under this Government, though.

As the cabinet hardened its tactics by agreeing to overturn a series of defeats in the House of Lords, a cross-party group of peers failed to introduce a pilot scheme before a new regime for disability allowances can be fully introduced. But Lib Dem cabinet ministers agreed with their Tory colleagues to overturn the amendments when the bill returns to the Commons.

Whilst it might suit some with social democrat ‘roots’ to wish the Liberal Democrat Party to ‘come good’, there is no evidence at all that would happen. Attempts to bring out this simple fact tends to become squashed with the attack that ‘Liberal Democrat’ votes are all to play for, and that LibDem MPs reading a fair discussion of this might change their mind from the party line.

LibDem MPs don’t work like that. Their motto, ‘fair society, strong economy’, is reflected in the UK only having performed very badly for three years and with the decimation of legal aid and law centres.

The hospital closure clause gives Trust Special Administrators greater powers including the power to make changes in neighbouring trusts without consultation. It was added to the Care Bill just as the government was being defeated by Lewisham Hospital campaigners, in an attempt to ensure that campaigners could not challenge such closure plans in the future. But the new Bill could be applied anywhere in the country.

Writing in the British Medical Journal, Professor Allyson Pollock said that that the clause would “undermine equal access to care in England” and removes “checks and balances designed to ensure that changes are in the interests of the communities affected” with Trust Special Administrators only having to consider market money.

Neoliberal means neoliberal. It means free movement of capital such that multinationals can buy parts of the NHS. It means everything is put out for competitive tendering. A social movement to pull on LibDems heart strings, with the unflappable Baroness Williams, will be a waste of time, but I suppose one should have dreams.

But dreams ought to be realistic. The Care Act, with its ‘closure clause’, will come into law, again only made possible through help of the Liberal Democrats.

#NHSChangeDay 2014: an opportunity for a distributed leadership to drive change to promote quality of life for people with dementia

Research from McKinsey’s and Company recently argued in a document entitled “What it takes to make integrated care work” that integrated care can be implemented in virtually any health system. However,

three elements are necessary to ensure success.

They are: a clear focus on specific segments/diseases, an emphasis on multidisciplinary care, and key support systems including clinical leadership and information sharing.

NHS Change Day 2013 was the biggest day of collective action for improvement in the history of the NHS. A countrywide event in England, NHS Change Day was a grassroots initiative devised and driven by a small group of emerging clinicians and improvement leaders. Their idea was to create a mass movement of National Health Service (NHS) staff demonstrating the difference they can make by one simple act, proving that large-scale improvement is possible.

You can read more about the NHS Change Day here.

NHS Change Day created a sense of urgency by focusing on a single day of collective action. In many cases Change Day provided the necessary prompt to galvanise and amplify activity that was already planned.

The story in fact began in 2012 when a conversation began on Twitter betweena GP and healthcare improvement thought leader. GP Dr Stuart Sutton had just attended Helen Bevan’s talk on “Building Contagious Commitment to Change” as part of the learning programme run for Darzi Fellows by the King’s Fund. Helen had worked for years to apply social movement principles to improving health care. Trained in community organising methods, Helen encouraged others in the NHS to learn from leaders of great social movements, people who had few resources, no hierarchical and positional power, but who delivered results by building power through collective action.

Pledges have come from many and different areas of health and social care (see “the Wall”).

My pledge is here.

Medications are not the only fruit.

@legalaware although a pharmacist, I don’t think we should rely on drugs for many conditions. Especially dementia

— Cathy Cooke (@Cleverestcookie) January 4, 2014

There is actually something very clever happening here with NHS Change Day – and could be a big deal for how the NHS and other caring establishments consider how to care in dementia.

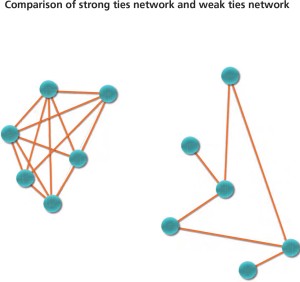

Distributed leadership highlights leadership as an emergent property of a group or network of interacting individuals. These individuals might include academics, carers, people with dementia, members of the public, innovators/passionate people in the NHS, private companies, community interest groups, corporates, social enterprises, and so forth. They do include medical thought leaders, experienced in the dementias and ethics, too such as Dr Peter Gordon (@PeterDLROW). This contrasts with leadership as a phenomenon which arises from the individual.

Also, contrasted with numerical or additive action (which is the aggregated effect of a number of individuals contributing their initiative and expertise in different ways to a group or organisation), concertive action is about the additional dynamic which is the product of group activity. Put simply, “the whole is greater than the sum of its constituent parts”. The idea of a power network having massive collective action is an altogether different way of doing things, compared to leaders in large charities or government having a lot of powerful and influence.

A distributed leadership suggests openness of the boundaries of leadership. This means that it is predisposed to widen the conventional net of leaders.

Furthermore, distributed leadership entails the view that varieties of expertise are distributed across the many, not the few.

There’s also an interesting narrative about ‘ties’, which is briefly touched upon in the de-briefing from last year’s #NHSChangeDay.

NHS Change Day created what one member of the core team called ‘thousands upon thousands of weak ties at the operational level.’ Quite simply – who knows who’ll you be speaking to on Twitter?

It could be Prof Burns, the national clinical lead for dementia (@ABurns1907).

“Our job is to put in place a platform and tools where we do nothing, but which enables other people to do it for themselves. That will enable change that we won’t even know is happening. We will provoke conversations and relationships between different groups of people in different parts of the NHS that will make lots of little changes that will build up to a big change.” (Joe McCrea).

My pledge for #NHSChangeDay explicitly asks people in health and social care to ask a person living with dementia – and/or carers – what their beliefs, concerns and expectations about living with dementia might be. Advocates for personal experiences of current living with dementia themselves must be a crucial part of that experience (for example Norman McNamara [@NormanMcNamara] and Kate Swaffer [@KateSwaffer]), as well as people who’ve had direct experience of the highs and lows of caring for someone with one of the dementias (such as the outstanding Beth Britton [@BethyB1886], Sally Marciano, Kim Pennock or Thomas Whitelaw [@TommynTour]). Outside medicine, nursing specialists clearly will hold the magic key (people like @lucyjmarsters). Leaders such as Lee [@dragonmisery] prioritise choice and control for carers by the provision of accurate, helpful and accessible information. I cannot express how much their wisdom far surpasses the knowledge of some so-called dementia ‘experts’ I worked with about a decade ago.

Gill Phillips (@WhoseShoes) knows exactly what I mean. Her innovation “Whose Shoes” emphasises the identity of a person, not the name of any diagnosis.

It’s not particularly that I wish ‘professionals’ to “take a back seat”, but that I feel that they have a different area of expertise. For example, it is not unheard of for clinicians helping big dementia charities to report a long list of potential conflicts of interest of funding from Big Pharma in publishing papers on dementia, while stating correctly they have no conflicts of interest for those large dementia charities. Indeed, in the world of evidence based medicine, very few medications which have been ‘recommended’ for Alzheimer’s disease, the most prevalent form of dementia globally, have been proven to have had a significant beneficial effect on quality of life or wellbeing.

To minimise any one particular group of stakeholders having an undue influence on dementia policy, it might be helpful to mitigate the risk by recognising other leaders from different groups. This is where person, patient and carer engagement in the dementias might be especially critical.

I am therefore mindful of a sense of “urgency”, akin the urgency of NHS Change Day. I don’t happen to be one of those people who thinks dementia is ‘solved’ by a medical Doctor reaching for his prescription pad, although some of the modest or good effects on memory and attention in some individuals with dementia are clearly to be welcomed.

This means a change in culture from the medical mindset to a more person-centred focus of nursing and social care, where there is of course a place for drugs. I do not dismiss the impact of pharmacological agents in dementia, having published myself a paper on methylphenidate and paroxetine in frontal dementia in Nature Neuropsychopharmacology and Psychopharmacology respectively. To arrive at this new culture of whole person or integrated care, it will be necessary to ‘unfreeze’ from the medical mindset, applying the seminal work of Kurt Lewin from last century.

The popularity of the pledge itself can be measured by the number of ‘likes’, but I suppose a more enduring legacy is whether for example doctors or nurses routinely ask about the person’s beliefs, concerns and expectations about wellbeing in a routine history. It’s hard to know whether this battle will have been won, until a special box for wellbeing starts perhaps appearing on clinical proforma sheets in hospitals or care homes.

I asked a Consultant in Department for Medicine for the Elderly in an English hospital whether my pledge might catch on. He advised sympathetically that he has ‘enough trouble’ getting his juniors to do an accurate history and examination in admitting patients in his hospital let alone asking about wellbeing which is so clearly relevant to someone’s hospital care. He then reminded me of how he had been asked to review a patient with dementia at 5 am the other week, and the night nurse had forgotten to turn off a bright lamp dangling down on her face while that patient was attempting to sleep.

I am particularly mindful of the difficulties with the term ‘living well’. For example, there are some individuals with extremely advanced dementia whose quality of life is observed as very poor. I think those involved in caring in any capacity still aspire that they can be somehow contented. I suppose that I am more concerned about persons in the earlier stages of dementia, although there is in fact a chapter in my book entitled, “Maintaining wellbeing in end-of-life care for living well with dementia.”

I have started a special Twitter account (@Dementia_Change) to discuss my pledge (a raw number of followers might serve as a useful metric, as well as the number of “likes” for the actual pledge.)

Many thanks to the organisers of #NHSChangeDay. I hope it receives worldwide attention as it did last year, as it is an outstanding initiative.

Not just medicalisation, but Alzheimerisation?

I asked some practising medics, including GPs, neurologists, and obstetricians, about the following case vignette. I had tried to eliminate mentions of the word ‘dementia’. The original vignette was published in an article in the Guardian this week, under the title, “My 70-year-old husband has turned aggressive – I fear he has dementia”.

“I enjoy his company: he is charming, intelligent and considerate. He has always had periods when he would become moody and unpleasant to me, but these are few and far between.

He is a bit forgetful, but he has had some bizarre memory lapses; he becomes aggressive if I mention it, sometimes says odd things, and has become hypersensitive to criticism. Recently, my husband lost his temper with me after what seemed to me a trivial matter, although it obviously wasn’t to him. His reaction stunned me. He started to scream at the top of his voice, then picked up the grill tray of the cooker. I thought he was going to hit me with it, but he turned and bashed the cooker repeatedly, leaving dents and marks. He then screamed abuse at me. He has not spoken to me since, but when he speaks to our boys on the telephone, he sounds cheerful and normal.

I have never seen him lose control so completely before, and worry that next time he may go for me. I don’t feel I can talk to him about this because I know that he would lose his temper again, and I dare not mention that I worry about his health. I feel the only thing I can do is to leave him. But I feel heartbroken and baffled that such a happy relationship could end like this and don’t know how to broach the subject of separation. What should I do?“

The article itself went to consider how the individual might seek confidential advice from a charity such as the Alzheimer’s Society. The background to this is that, previously, the Alzheimer’s Society, a large charity, in partnership with the Department of Health launched a national campaign to address the ‘diagnosis gap’, of individuals not receiving a clinical diagnosis of dementia. With a series of videos and huge coverage, including the G8 dementia summit which was publicised heavily in the national media, a new map of diagnosis rates nationally has been launched.

Alzheimer’s disease is the main presenting form of dementia globally, although there are in total over hundred types of dementia. Prof John Hodges, who has written one of the Forewords to my book “Living well with dementia”, has reviewed the medicine of the dementias in his chapter for the Oxford Textbook of Medicine (available here).

It is generally considered that memory problems constitute the main picture of the clinical presentation of “typical” Alzheimer’s disease. In contrast, in a common dementia in the slightly younger age group, called frontotemporal dementia, the dominant presentation can be one of an insidious personality or behaviour change. Depression can easily be confused with dementia, in that depression can cause memory problems and changes in personality.

There are further issues at play. Because of artefacts in their training, a neurologist is more likely to be asked to diagnose a dementia, and a psychiatrist a depression. A GP seeking a specialist opinion might prefer locally to refer to a psychiatrist rather than a neurologist in their locality, as the waiting time is shorter.

And the G8 dementia summit has caused a lot of problematic issues to resurface. The Summit itself spent much more time in discussing data sharing of genomic and drug trial information, with a view to developing personalised medicine, in other words treatment and cure, rather than in discussing the often inadequate resources for frontline care in specific jurisdictions including the UK. Rather than closing down the ‘cure vs care’ debate, the G8 summit has instead thrown the debate into the spotlight; see for example the separate useful contributions from Beth Britton and Prof Peter Whitehouse.

But the odd phenomenon is now emerging that not only has their being growing medicalisation of the dementias, with such a focus on diagnosis, treatment and cure, but the focus has been like a targeted missile strike; it is “Alzheimerisation”, meaning that even all possible dementia presentations all go down the final common diagnostic pathway of Alzheimer’s disease.

There is already an interesting pre-existant literation on “Alzheimerisation”. My friend in Adelaide, Kate Swaffer, has referred to the phenomenon on her popular and leading blog (blogpost here).

A critical path in producing the correct diagnosis and differential diagnosis is the age of the patient and spouse. I unhelpfully didn’t include this information.

The points raised by the Consultant Paediatrician by training were therefore generic points which could have helped, whatever the diagnosis was. He queried: Has he got or recently had physical illness? Is he anxious or depressed? He then suggested he would “triangulate views” with other family members, friends etc. This Paediatrician immediately latched onto the difficult ethical issue in this problem, stating: “Don’t provoke him with a direct approach but he needs help.” As a person of his status in the NHS, he then queried sensibly as to whether he had seen GP recently, with a view to elucidating a recent medical history. Intriguingly, the Paediatrician did not shut down non-dementia diagnoses. In fact, he never mentioned dementia once (but this to be expected as dementia is far less common presentation in child and adolescent medicine/psychiatry than old-age for example.)

Another clinician, actively involved in his Royal College (for Obstetrics and Gynaecology) for training and other issues, came straight to his point:

“The only diagnosis going through my mind is dementia. However still need to consider acute confusional state. Also maybe thyroid disorders, vitamin deficiency, drug or alcohol abuse or depression.”

Interestingly, the Consultant Neurologist did pick up on the dementia twang of the history, but was more concerned about what type of dementia it might be, given the observed differences between Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia.

That Neurologist remarked:

“Hard to be specific given limited info, but given personality change I’d wonder about FTD, would want to know though about other things eg alcohol history or substance abuse, past psychiatric history, family history. Being vague but then the details are vague.”

But even there that neurologist in question did not shut down non-neurology diagnoses – neurologists on the whole do not do the “acute medical take” in the majority of hospitals – and produced a good range of medical/psychiatric alternatives.

In contrast, a General Practitioner was hugely concerned about the social/cultural dimension, and the overall ethical issues.

“Assuming it is the wife that is consulting me, I would:

Encourage her to contact the police, especially if there are further episodes of violence

Refer social services if children living in house, esp if witnessed episode (doesn’t sound like they are from your blurb)

Encourage her to move out, at least temporarily

Give her details of women’s refuge

Tell her to advise him to consult his GP as difficult to help medically otherwise.Your description makes me think about neuropsychiatric problems rather than just adjustment/personality/relationship difficulties. I don’t know how likely it is that I would get that flavour from the wife. However, abrupt change in personality, saying odd things and bizarre memory lapses would be a concern.

If the husband consulted me, depending upon my assessment (which would certainly include consideration of drug and alcohol use and perceptual disturbances), I would be thinking about referral to psychiatry, not because I think a physical problem unlikely but because I suspect it might be quicker than neuro. However, I might seek advice from a neurologist.

As for 10 minute appointments, the first with the wife would over-run. The assessment of the husband might take place over 2-3 appointments, after which there would be a fair amount of time taken up with considering/arranging referrals.”

After having read the discussion in the Guardian article, and clearly with the benefit of knowing the age of the person and his spouse, that General Practitioner picked up further on the ethical issues: