Sexuality and personhood cannot be ignored for persons developing a dementia

Many of us have been in the situation where one bit of serious event is quickly followed by another serious event. Imagine, having just been told that you may be developing a dementia that you feel forced then to tell the medical establishment that you’re in fact gay, and you’re actually a very private individual. Many elderly LBGT individuals now became adults in a time when homosexuality was considered to be unnatural, wrong, deviant and the basis for discrimination. If you were a gay man aged 80 today you may have developed your sense of identity and self-worth in a secret world where people like you hid their identities and maintained a very different public persona. You would have been 44 when the American Psychiatric Association declassified homosexuality as a mental disorder in 1973.

The past of medicalising homosexuality is indeed inglorious as described here. Evelyn Hooker’s pioneering research in the 1950s is said to have debunked the popular myth that homosexuals are inherently less mentally healthy than heterosexuals, leading to significant changes in how psychology views and treats people who are gay. In conjunction with other empirical results, this work led the American Psychiatric Association to remove homosexuality from the DSM in 1973 (it had been listed as a sociopathic personality disorder). In 1975, the American Psychological Association publicly supported this move, stating that “homosexuality per se implies no impairment in judgment, reliability or general social and vocational capabilities…(and mental health professionals should) take the lead in removing the stigma of mental illness long associated with homosexual orientation.”

This is yet another example where it matters that you’re a person not a diagnosis. How you’re navigated from that point through the care services, quite clearly, is not just a matter of law (equality law which should legislate against you being discriminated against), but is also a matter of culture. Whilst cultural attitudes to LGBT citizens, it can only be the case that once you’ve met one LBGT person you’ve only met one LBGT person, in the same way once you’ve met one person developing dementia you’ve only met one person developing dementia. Nonetheless, it is important for policy-makers, care providers and the general public to have a working approach to people who happen to be LGBT encountering the care services. For many people now, it is near impossible to imagine what it was like to live in constant terror of being discovered. Just 50 years ago, staggeringly, there was no protection in law from prejudice and discrimination, and it was unthinkable that gay relationships could be formally acknowledged through a civil partnership. It turns out that a high percentage of older LGB people have experiences of mental health problems, including an increased risk of suicide attempts and selfharm. The recent Opening Doors survey (Phillips and Knocker, 2010) found that one-fifth of respondents had experienced a mental health problem in the past five years.

As Sally Knocker (@SallyKnocker) describes in her report “Perspectives on ageing: lesbians, gay men and bisexuals” for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (January 2012),

“It is difficult to be sure of the size of the older lesbian and gay population, as there are still no census figures regarding sexual orientation. Stonewall estimates that 5–7 per cent of the population is gay or lesbian, and this estimate is accepted by government agencies. The total population of people over the age of 55 living in the UK is 17,421,000 (based on 2009 mid-year statistics) and 5–7 per cent of this is between 871,045 and 1,219,470 people (roughly equivalent to the population of Birmingham). Older lesbian and gay people therefore make up a very sizeable minority community, yet their views are rarely sought as a distinct group.”

Not all people with dementia are old, but there are potentially two effects at play here. Ageism is stereotyping and discriminating against individuals or groups on the basis of their age. The term was coined in 1969 by Robert Neil Butler to describe discrimination against seniors, and patterned on sexism and racism. Likewise, everyone has the right to access healthcare, regardless of their sexuality or gender identity. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transsexual people may have poor experiences of health services or social care because of negative attitudes to sexuality or gender identity. This may include an assumption that someone is heterosexual, discussing a patient’s sexuality when it’s not relevant to their care, or refusing care because of their gender identity or sexuality. Negative experiences of health or social care professionals should not discourage you or the person you care for from seeking treatment. The Equality Act [2010], legislated in the final days of the last Labour government, makes it unlawful to discriminate on the grounds of sexual orientation or to discriminate against someone who intends to undergo, is undergoing or has undergone gender reassignment, in such a way that acts to a detriment.

The various definitions are as follows:

- Lesbian : a woman whose primary sexual and emotional attraction is towards other women

- Gay (can be used for both gay men and lesbians) : a person whose primary sexual and emotional attraction is to the same sex

- Bisexual : a man or woman who is sexually attracted to both men and women

- Transgender : a man or woman whose gender identity is at odds with their biological sex

- Intersex : a person born with sex chromosomes, external genitalia or an internal reproductive system that is not exclusively male or female

It’s an important issue as reduced access to networks of gay or lesbian friends, gay or lesbian interest or social groups and to the broader lesbian and gay communities have been found to contribute to reduced health outcomes for lesbian and gay people with dementia. This can lead to social isolation and loneliness, itself leading to stress and depression, and therefore the general wellbeing of LBGT persons living with dementia may be under pressure for a plethora of reasons.

Encouragingly, however, policy, in its general direction of appreciating the ‘I am a person not a diagnosis’ mantra, has applied personhood to thinking about sexuality in persons with dementia, in a way which might have happily surprised even the late Tom Kitwood himself. In Heather Birch’s “It’s not just about sex! Dementia, Lesbians and Gay Men” presented at the Alzheimer’s Australia Conference, Adelaide 2-5 June 2009, Professor Dawn Brooker’s message about person centred care was cited at the plenary session, viz:

Paul and Mark had been together for almost 20 years when Mark was diagnosed with dementia. When Mark went into aged care, Paul felt that his world was torn apart. He wanted to tell staff that his partner is the same person that he met and fell in love with, and how much pain he felt when Mark didn’t always recognize him. He wanted staff to know that dementia didn’t differentiate between a gay or heterosexual person. He wanted to tell them he had the same trauma and grieving and that he loved his partner like heterosexual couples do. He didn’t tell staff, because he didn’t know if they would understand.

And yet a person who does not feel easy with expressing sexuality is hugely problematic for an approach based on personhood.

[Source: slides of a talk entitled "IN or OUT of the CLOSET: ending the invisibility of LGB and TI people in dementia, ageing and aged care services" by Norman Radican, LGBTI Project Officer and CaLD Liaison Officer, Access and Equity Unit, Alzheimer’s Australia SA.]

A body of work looking at the experiences of LBGT individuals in health and social care contexts and the ways in which they navigate the disclosure of their sexuality to service providers unfortunately confirms the presence of homophobia (irrational fear of, or aversion to, gay or lesbian people) and heterosexism (the assumption that all people are heterosexual and that heterosexuality is the only “permissible” sexuality). A critical issue for respondents in the study by Brotman and colleagues (Brotman et al., 2007), for example, was the fear of having to come out to service providers or, worse, of having forcibly to “return to the closet”. These concerns align well with research undertaken in the UK exploring the experiences of ageing as a gay man or lesbian woman. Only 35% of respondents in the study by Heaphy and colleagues (Heaphy et al., 2003) study, for example, were likely to be positive towards gay and lesbian service users, and respondents described differential treatment, experiences of hostility and a generalised lack of understanding of their lifestyle choices. Disappointingly, they generally understood health and social care providers to operate according to heterosexual assumptions, meaning there may be a generalised failure to address their specific needs. For many of the participants in this study, the entry of service providers into their lives was the pivotal point at which their sexuality became evident to others, as their previously private lives were exposed to public scrutiny and they were thus obliged to decide whether or not to come out to service providers.

In a paper entitled “??????????????????????????????????Coming out to care: gay and lesbian carers’ experiences of dementia services”, Dr Elizabeth Price from the University of Hull reports on findings from a qualitative study, undertaken in England that explored the experiences of 21 gay men and lesbian women who care, or cared, for a person with dementia. The aim of the study was to explore how a person’s gay or lesbian sexuality might impact upon their experience of providing care in this context. Data collection occurred over a 4-year period. The authors concluded:

“It is perhaps time, therefore, for service providers to begin to critically consider their attitudes and responses to carers whose social identities are increasingly diverse, for the ways in which those responses are framed can impact significantly on carers’ experiences of service pro- vision and the relationships they share with providers and, more importantly, the people they support.”

“Psychological security” is therefore an emergent theme which Sally Knocker describes elegantly as follows on Darren Gormley’s (@mrdarrengormley) blog:

“The first core need seems to me to be one of psychological safety. A great deal of emphasis is placed on keeping people physically safe, but emotional safety can be harder to measure or safeguard. Those of us who are gay and lesbian will have spent a lot of our lives making almost daily assessments of whether we feel safe to be open about who we are – whether it is booking a double bed in a hotel, meeting someone new at a party, going to the doctor or buying a book or a magazine.

We will be used to be being vague about our partners, using ‘they’ rather than ‘she’ or ‘he’. We will constantly try to gauge whether the person in front of us in a social or work situation is likely to be judgemental or relaxed. If someone is religious, does this mean that they are more likely to think I am a ‘sinner’ or someone to be pitied or ‘saved’? Is a younger person less likely to be shocked? Am I safer in a big cosmopolitan city like London or Manchester than I will be in a village in Derbyshire or in Wales?”

And Sally describes that communication is a pivotal aspect of this:

“We therefore need all health and social care professionals coming into contact with people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual or trans to give plenty of positive indications that they ‘don’t have a problem’. As a personal example of this, I remember a midwife visiting our home shortly after our daughter was born. She was an older black woman with a Christian cross round her neck and I am ashamed to admit that my own prejudices and assumptions about age, culture and religion kicked in, so I felt very apprehensive about how she would react to my partner and me.”

Trust therefore becomes a key issue. LGBT individuals and their partners and friends will need reassurance that their rights to privacy will be respected. Dementia may mean a reduction in the ability to conceal and self-censor behaviour and information disclosure.

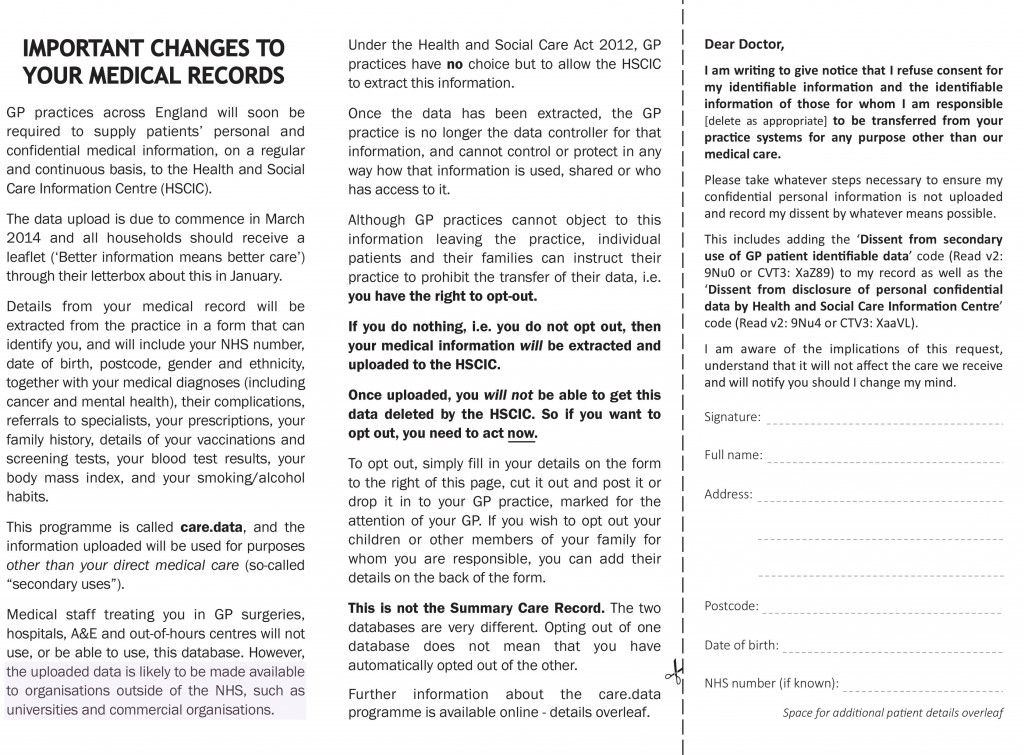

LGBT individuals may also have concerns about confidentiality, uncertain about who may have access to their personal information. As the data sharing drive continues in the NHS, this may become more of a policy issue in the forthcoming years. This fear may be based on previous bad experiences, and may not trust in representatives of authorities, official organisations and institutions. They may think a care worker will judge them, pity them, avoid physical contact, treat them as an object of curiosity, betray confidences, provide poor quality services or reject them. And for persons with dementia in residential care, other residents, with whom they share very little in terms of life experience or way of life, may demonstrate prejudice towards a non-heterosexual resident or their family of choice. This of course incredibly difficult to ‘legislate against’. Services may be designed on the fundamental assumption that people using their services are heterosexual. In such a system, LGBT individuals then become invisible.

Personhood is all about challenging assumptions, which we can all make without a malicious bone in our body. The problem with some of these assumptions is that they can lead to quite hurtful prejudices, especially when consolidated in how our culture operates. The fact that not some persons with dementia are young of course challenges a yet further assumption, and imagine if you’re that person who not only has to tell the whole world about your sexuality but also you’re most probably developing one of the dementias. The medical model is in an excellent position to ignore these challenges, but to do so would be a massive failure. There’s no doubt we’ve come a long way, but, as is so often the case, it’s not only a case of where you’ve come from but also where you’re ultimately going to.

References

Brotman S., Ryan B., Collins S., et al. (2007) Coming out to care: caregivers of gay and lesbian seniors in Canada. The Gerontologist 47 (4), 490–503.

Heaphy B. & Yip A.K.T. (2003) Uneven possibilities: understanding non-heterosexual ageing and the implications of social change, available at: http://www.socresonline.org.uk/8/4/heaphy.html.

Phillips, M. and Knocker, S. (January 2010) Opening Doors Evaluation The Story So Far… Executive Summary, available at: http://www.openingdoorslondon.org.uk/resources/Opening%20Doors%20Evaluation%20Report%20-%20Executive%20Summary%2023%2002%2010%20(2).pdf

Price, E, (2010) “??????????????????????????????????Coming out to care: gay and lesbian carers’ experiences of dementia services”, Health and Social Care in the Community, 18(2), pp. 160–168.

Book launch for ‘Living well with dementia’ and full details

Picture above of Norman McNamara (left) and me at the Queen Elizabeth II Centre yesterday.

A summary of the book and a programme for the book launch (by invite only) is here.

Here is the cover with Charmaine Hardy’s flower pictures. Charmaine Hardy is a key #dementiachallenger (@charbhardy).

Links to material

Amazon page

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Living-Well-Dementia-Importance-Environment/dp/1908911972

Publishers page

http://www.radcliffehealth.com/shop/living-well-dementia-importance-person-and-environment-wellbeing

Contents

Dedication • Acknowledgements • Foreword by Professor John Hodges • Foreword by Sally Ann Marciano • Foreword by Professor Facundo Manes • Introduction • What is ‘living well with dementia’? • Measuring living well with dementia • Socio-economic arguments for promoting living well with dementia • A public health perspective on living well in dementia, and the debate over screening • The relevance of the person for living well with dementia • Leisure activities and living well with dementia • Maintaining wellbeing in end-of-life care for living well with dementia • Living well with specific types of dementia: a cognitive neurology perspective • General activities which encourage wellbeing • Decision-making, capacity and advocacy in living well with dementia • Communication and living well with dementia • Home and ward design to promote living well with dementia • Assistive technology and living well with dementia • Ambient-assisted living well with dementia • The importance of built environments for living well with dementia • Dementia-friendly communities and living well with dementia • Conclusion

Introduction

There are probably close to one million people currently living in the UK with one of the hundreds of dementias, it is thought.

Plan [by prior invitation only]

Please do not attend if you have not been invited – there are strict limits for both venues.

Saturday February 15th 2014

3 pm I will give a talk on ‘Living well with dementia’ at the Arlington Centre, 220 Arlington Rd, London, Camden NW1 7HE.

I will introduce my book, and how this has become a critical plank in English dementia policy. this will be followed by tea and coffee for my guests to meet each other.

The book will be available to see (due to be published on January 27th 2014), and arrangements will be made for the book to be made available at a discounted rate from the publishers.

7 pm Dinner at Pizza Express, Southampton Row, London. WC1

(near the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, London), 114-117 Southampton Row, London.

Background

There is actually surprisingly little awareness of what “wellbeing” and “living well” actually mean. In the absence of an understanding of the academic background to these terms, they are at risk of being used as merely marketing devices. And yet, their relevance is very real. The Care Bill is just one recent example of a statutory instrument where wellbeing has to be given priority in commissioning decisions, and be seen to do so.

Sadly, relatively uniquely, I have nothing to gain particularly by discussing these ideas. I did my own Ph.D. in dementia at Cambridge, and, also from a medical background a long time ago, I hope that I can give a balanced, accurate account of some of the policy decision-tree in dementia in England. “Living well with dementia” is, in actual fact, the name of the five-year national dementia strategy for England, which is (hopefully) about to be renewed.

A diagnosis should not be the first step to medical professionals or the rest of society in writing an individual off. My views are deeply entrenched in inclusivity, reciprocity and solidarity, and so it will not surprise you that I do not feel myself in competition with anyone. The people who are most influential to me in my view of the dementias, as an academic, are those people living with dementia. I hope many of them are living well, but it should be the aim of everyone for us all to live better. My book hopefully is a realistic look at various policy planks, including the proposed use of assistive technology, better design of the home and built environments, forming stronger communities, and promoting various lifestyle activities.

It’s an important narrative which has a huge amount of evidence about it, and my simple aim has been to take it out safely out of the worlds of academia and wonkland, and to bring it to the general public. I hope you enjoy my book!

What is “living well with dementia”?

This book is quite unusual as it is not a medical textbook, and yet I feel the book would enormously helpful and interesting for senior doctors working in this specialised area. There are common myths about ‘living well’. It’s not just about happiness. It’s not simply the absence of illness. It’s about something uniquely and personal. For any one person, it’s a complex interplay of cognitive factors (such as reasoning and memory), mood, and psychological and physiological wellbeing (such as physical and social factors). One of the earlier chapters is devoted to discussing the various definitions of ‘living well’, and how this might possibly be measured.

I believe, pretty, strongly that this is not a sterile academic debate. It’s about fundamentally what we’re like as persons, our interaction with one another, our interaction with the environment, quality of care, and properly funded health and social care services. The medications which have been developed sometimes have been marketed with rather hyperbolic claims, but for many the ‘anti-dementia’ drugs known as cholinesterase inhibitors have rather modest effects. Meanwhile, the reality is funding for community clubs encouraging people with dementia to meet up and participate in activities has been threatened, and funding for advocacy for certain persons with dementia to defend their legal rights has been withdrawn altogether.

“Dementia” is likewise not an unitary phenomenon. The term ‘dementia’ is often used synonymously with Alzheimer’s disease, which does typically present with memory problems, but there are hundreds of different types of dementia in the world, some of which do not even present with memory problems. This conflation in language has hampered a cogent narrative on how we diagnose dementia – and there is currently concern that some individuals are receiving a diagnosis of dementia rather too late – and how we ‘cure’ dementia. Knowing what type of dementia a person may live with (the cognitive neurology) can potentially allow people to be on the lookout for potential challenges that person might face – e.g. spatial navigation, which could be addressed through appropriate signage in the external environment. Knowing what type may also be particularly relevant to communication techniques, but often basic things in conversation can often be poorly done quite disappointingly.

I got through my entire undergraduate medical training at Cambridge, and indeed a neurology foundation year job at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery at Queen Square, without ever knowing about Tom Kitwood’s seminal work on “personhood” (1997). And yet this concept of persons with dementia, rather than necessarily patients, is fundamental to how I feel about this subject. I have a few friends with dementia. I learn loads off them. If one friend, for example, supports surveillance monitoring through GPS tracking, I support him or her. If it’s considered to be an unacceptable intrusion on personhood, I respect that too. But the point is, I don’t think it’s right for others to “judge” what people can’t do – it’s what persons with dementia can do which counts. I do not discuss factors involved which may contribute to delayed diagnosis across a number of jurisdictions, but I do address how English policy has attempted to identify people with dementia.

I wear a number of ‘academic hats’. One of them is, surprisingly, innovation management. You’ll see this influence in my book towards the end. I think of persons with dementia as part of the ‘network’ needed to bring about a cultural change in how healthcare views dementia, in a form of “distributed leadership”. In this network, there are many actors, not just the “usual suspects”. Adoption of innovations also looms large in my book, with two chapters devoted to assistive technologies (and the research behind them) and ‘ambient assisted living innovations’. It’s just incredible to think how much progress has been made in this area, ranging from output from the Design Council to that from massive EU-funded initiatives. Ultimately, there’s a good economic case as well for promoting living well with dementia. Nonetheless, whilst being optimistic, I have endeavoured not to produce a sanitised version of ‘living well with dementia’: I describe for example living well in end-of-life care, and particular phenomena which might be particularly relevant here.

But the problem with wearing so many hats is that you can all too easily enter a ‘silo mentality’. It’s though definitely the case the various topics do connect together. Whatever your views about the policy drive towards a ‘timely diagnosis’, a prompt and correct diagnosis can potentially lead to better care. Housing is one of the important ‘social determinants of health’, and attention to what works best in the external environment and through design features of the home can massively improve the quality of life of a person with dementia. Hospitals can be very disorientating for patients with dementia too, and this must be borne in mind when designing a ward environment – patients with dementia represent a high proportion of acute presentations in the elderly too. And adopting a community-oriented approach means that a person with dementia is a friendly and supportive environment, and this of course requires some ethical reconciliation with the themes of autonomy and independence. This has been an important converging area of policy, and goes including the person with dementia in any decision-making, reflecting key aspirations of choice and control (whatever your ideological viewpoint).

The main aim of this book is to take the discussion out of a specialist area, in such a way that we – as citizens – can all discuss the issues involved, and come to an informed opinion. I hope therefore you enjoy the book!

Key reference

Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Buckinghamshire: Open University? Press.

Lucy Reynolds is back – a chat with Bob Gill on how the marketing of NHSprivatisation has been tweaked

This was the front page of the Daily Mirror at the time.

The original video is here.

This video is a follow up on Dr Lucy Reynolds’ earlier analysis of the government’s ongoing programme to privatise the NHS by stealth.

Talking to local GP Dr Bob Gill (@drbobgill), she also elaborates on measures people can take to head off this programme, particularly in relation to the House of Lords debate on April 24th.

Disclosing the dementia diagnosis – where can the delays occur?

There’s been a lot of heat and frustratingly little light in the discussions in where the delays might occur in disclosing a diagnosis of a possible dementia. At worst, politicians and influential others (largely not medically qualified) have given the impression of ‘coasting’ GPs slowing down the process. But this would be to simplify an extremely complicated issue in such a way that causes considerable damage in English policy concerning dementia.

There are significant differences in the percentage of people with dementia receiving a diagnosis in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In 2012, for example, it was estimated that 39 per cent of people in Wales had a diagnosis, 44 per cent in England and 63 per cent in Northern Ireland. As a result, the prime minister’s challenge on dementia aimed to increase diagnosis rates by two thirds by 2015, and the Scottish Government launched a similar initiative. Last year, a paper first presented in September at the “Preventing Overdiagnosis conference” in the United States – and subsequently published in the BMJ – suggested that the drive to screen people for minor memory changes, often called pre-dementia or mild cognitive impairment, risks doing more harm than good.

The authors, led by David Le Couteur, professor of geriatric medicine at the University of Sydney, warned that expanding diagnosis in dementia would result in up to 65 per cent of people aged over 80 being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, and up to 23 per cent of older people being wrongly labelled as having dementia. The authors argued that the trend for screening older people for minor memory change in the UK and the US is leading to unnecessary investigations and potentially harmful treatments; and that is diverting resources that are needed to care for people with advanced dementia. However, the benefits of a timely diagnosis are seen to be longer periods of higher quality life supported at home. Major consequential savings in hospital in-patient and residential social care costs are anticipated. Policies are favoured that deliver personalised support packages for people living at home, it is hoped, night be contemplated at the earliest juncture.

There are currently international variations in the opinions of family members and informal carers about whether they believe a diagnosis should be given to their loved ones. The obvious tension between doing no harm and giving people the right to make a decision about whether they wish to receive their diagnosis is an important bioethical debate. A study conducted in Brazil (Shimizu et al 2008) found that only 58 per cent of carers of people with dementia believed the diagnosis should be disclosed. In a similar study in Taiwan, this number was 76 per cent (Lin et al 2005) and in a study in Finland (Laakkonen et al 2008), 97 per cent of carers believed diagnosis should be disclosed to their relative. A study in Belgium (Bouckaert and van den Bosch 2005) found only 43 per cent of relatives supported disclosure, while in Italy, Pucci et al (2003) found only 39 per cent of relatives favoured disclosure. While the reasons for this global disparity are unclear, these are important considerations for nurses to be aware of before engagement with families of people with dementia. This disparity is perhaps a reflection on the uniqueness of people with dementia as well as the attitudes and feelings of their families.

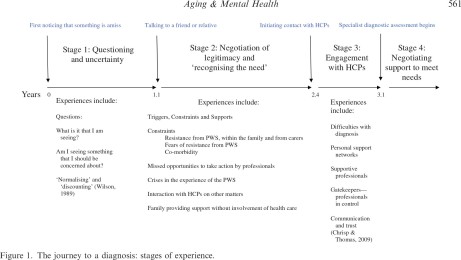

The present interest in the UK in bringing forward diagnosis of dementia requires insights into the journey taken by people with dementia and carers on their way to reaching a diagnosis. (Please note that there are some persons with dementia who’ve said publicly in the past in the social media, “I am not on any journey.”) Early work had described a timeline of changes and events that occur during the journey of a person with dementia and their carers – in particular: first noticing that something may be amiss, first talking to a friend or family member about it; stopping driving; needing help with daily activities; first contact with a physician and receipt of a diagnosis. Key findings from that earlier work are that it took on average 1 year for the carer or the person with symptoms (PWS) to talk to a friend or family member.

An important aim of a paper by Tom A.C. Chrispa, Sharon Tabberer, Benjamin D. Thomas and Wayne A. Goddard, entitled “Dementia early diagnosis: Triggers, supports and constraints affecting the decision to engage with the health care system”, published in Aging & Mental Health [Vol. 16, No. 5, July 2012, 559–565] was to identify influences on people’s decisions to make first contact with an HCP. The data suggest that carers of people with the symptoms of dementia who live at home are very often the ones to generate the first action to contact an HCP.There is very often a lengthy delay between first noticing symptoms of dementia and making first contact with Health Care Professionals (HCPs). This article identified influences on the decision to contact HCPs for the first time through a ualitative thematic analysis of 20 case studies of carer experience. Participants were carers of people who attended Memory Clinic services.

In only 2 of their 20 cases did the PWS actively make the first contact with an HCP to discuss their symptoms. In 13 cases, the carer was the main agent effecting the first engagement with HCPs. In one case, the carer and a social worker were closely involved together in deciding to engage HCPs. In three cases, a medical professional directly prompted a discussion with other HCPs about the issue. In one case, a non- medical professional initiated the first contact with HCPs.

A diagram of their key stages is helpfully provided by the authors:

Stage 1. The time between thinking something may be amiss and the time of first talking to a friend or relative about this.

This stage is on average 1 year in length. It is a period where the carer has noticed that something is amiss but they have yet to articulate their concerns. Delays in contacting others may arise due to carer’s fears of the resistance that the PWS may have towards the involvement of HCPs. The demands that other medical conditions place on carers can also provide a distraction.

Stage 2. The time between first talking to a friend or relative about this and first contacting an HCP to discuss the symptoms.

This stage is on average 1 1/3rd years long. Family members may resist the involvement of HCPs. Sometimes, it was the carer themselves and sometimes, it was other family members who resisted involving HCPs. There were debates among family members about what was being observed. An issue might be: “Is it just ‘old age’?” Families might on occasion disagree about the nature of symptoms but agree that care was needed and provide additional care support at home without involving HCPs. Sometimes the internal discussions concluded that the symptoms were not caused by a ‘health problem’.

Interestingly, the authors report that carers did not always recognise at first that HCP involvement might be an appropriate response to the behaviours being witnessed. Sometimes, it is a ‘trigger’ (an event, a build up of evidence) that is required to enable the carer to feel they have the necessary legitimacy to contact HCPs.

So it is clear from this initial paper that this unsightly slanging match between professionals, the public and politicians might be barking up completely the wrong tree. The dynamics in the relationship between the person with symptoms, and those closest, who might include friends and family, are undoubtedly critical, and I’ve been struck how this might be particularly important in the early onset dementias. In an important paper entitled, “The experience of caring for a partner with young onset dementia: How younger carers cope”, by Shirley Lockeridge and Jane Simpson in the journal Dementia, the authors describe explicitly a phenomenon of: “‘This is not happening’: carers’ use of denial as a coping strategy.” For example, in the behavioural variant of the frontotemporal dementia, the presentation is not problems in memory, but rather an insidious change in behaviour and personality noticed primarily by others not the person himself or herself. And possible explanations offeredfor the changes in the behaviour and personality of their partner, according to Lockeridge and Simpson, have been rather varied, including post-viral fatigue, a brain tumour, stress at work and a ‘mid-life crisis’:

However, according to the authors, as time passed, younger carers and their partners began to adopt more emotion-focused strategies:

“This originated in the reluctance of their partner to acknowledge that they were experiencing any problems which meant that most carers had to use excuses and subterfuge in order to persuade their partner to attend medical appointments and assessments. Carers found that they experienced increasing anxiety as their partner’s behaviour deteriorated and their need increased to have clandestine discussions with their GP, with employers and with banks to take control of financial matters. Carers described using avoidance as a way of coping with the changes in their partner and spoke of behaving like an ‘ostrich’, ‘burying their head in the sand’ and ‘pretending’ that their partner’s problems were not serious. Carers were also acutely aware of their partner’s denial of their symptoms and described feeling as if they were adopting a ‘cloak and dagger’ approach to hide any information about dementia from their partner. Carers reported trying to maintain everything as ‘normal’, even up to the point of diagnosis.”

In an equally intriguing paper, “The personal impact of disclosure of a dementia diagnosis: a thematic review of the literature” by Gary Mitchell, Patricia McCollum and Catherine Monaghan in the British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing [October/November 2013 Vol 9 No 5]. the authors reviewed that decisions around disclosure of a diagnosis of dementia are not always patient-centred. The authors argued that a plethora of literature supports the notion that physicians do not always clearly and directly disclose the diagnosis to the person with dementia. The authors found that Bamford (2010) had suggested that the global rate of non-disclosure is around 40%. There are several reasons for this, but arguably the most pertinent is the emotional distress disclosure can potentially cause. This emotional impact can undoubtedly a crucial factor in carers’ attitudes and practitioners’ variability in disclosing the diagnosis to their patients, it is argued (Robinson et al, 2011).

The findings of this review indicate that people who have recently experienced a diagnosis of dementia have feelings ranging from anxiety or fear to relief, or the enablement of future planning. Despite this mixture, the perceived stigma surrounding a diagnosis of dementia was evident in the majority of the literature. The act of non-disclosure, which is common globally, is a decision often taken by physicians or carers in a bid to promote non-maleficence (“do no harm”). The authors argued that numerous studies have demonstrated that family or physicians often conclude that beneficence or non-maleficence out- weighs the person’s autonomy and that a disclosure of the diagnosis of dementia to the person will cause harm; by withholding this knowledge the physician and/or family believe they are collectively doing good.

Non-disclosure can also be analysed through the prism of Tom Kitwood (1997) and his model of “malignant social psychology”. Malignant social psychology pertains to an environment where the person with dementia is treated differently owing to their being diagnosed with dementia (Kitwood, 1997). Key components of this model are disempowerment, infantilisation and withholding. Through non- disclosure, people with dementia have their diagnosis withheld by physicians or carers because of the poten- tial harm it could cause (infantilisation). This can ultimately serve to make the person with dementia more passive in their care (disempowerment).

There has been unsightly amount of finger pointing as to “who is to blame”. Often in the firing line is ‘primary care’ as the point of first point of contact for people with suspected dementia in ensuring early detection and effective ongoing management. Collaboration between general practices and specialist services is therefore essential to ensure a smooth pathway to diagnosis. Collaborative care is essential in the management of long term conditions, but joined-up working between specialist dementia services such as memory clinics does not appear to be comprehensive or universal. Memory service investment and access varies hugely across the UK. And with the current implementation of the Health and Social Act (2012), acting as a driver to privatised, fragmented services, there is a genuine risk this will get worse.

Furthermore, evidence reveals that the average UK consultation time varies from 7.4 to 11.7 minutes. As older people often present with complex health and social care needs, length of appointment time may be a barrier in meeting their diverse needs. Furthermore, there are people susceptible to dementia who may not have access to a GP or specialist support services such as those from deprived populations, the oldest old people or those without support networks. For true inclusivity and equitable access to health care, services might need to be much proactive in reaching out to those in communities who remain unregistered with general practice and lack access to care, regardless of social and cultural background and geographical location, and also taking into account cultural barriers to diagnosis.

The role of the nurse in raising awareness and improving the lives of persons with dementia has recently been come under sharp focus.While GPs may not be able to pick up on the early signs and symptoms of dementia with the constraints posed by the general practice setting, nurses work at the interface between the patient and their social environment and are therefore well placed to notice the early signs and symptoms of dementia . Prof. June Andrews, director of the Dementia Services Development Centre at the University of Stirling, and a former director of nursing, has argued clearly that she understands that testing for dementia at an early stage carries risks – but they are risks she would be willing to take.

Professor Andrews would like to see a greater role for nurses in dementia diagnosis, both in hospitals – particularly A&E – and the community.

“The logical and humane way forward is to emphasise the role of the nurse. The usual diagnosis points – GPs and psychiatrists – can be high quality, but you sometimes end up with a backlog, which means that people do not get the benefit of diagnosis. The risks of nurse-led diagnosis are small.”

An example of successful, collaborative working in practice is the Community Dementia Nurse (CDN) Service launched by 2gether NHS Foundation Trust (2011) in Gloucestershire. The CDN service is innovative in providing specialist and direct support regarding dementia to GPs.The role covers advice and support with diagnosis, management and treatment of dementia and care plans designed to address immediate care needs. However, this is targeted at those within populations who have access to GP surgery.

So, this is most definitely ‘work in progress’. The frustration of many who have felt that the diagnosis of dementia has been unnecessarily delayed is a very serious one. But blame is not particularly constructive, nor motivating for a service already at full stretch. And it is clear now that the problem embraces a number of problems, not confined to education and training standards of the current NHS workforce, but the extent to which those closest to people with dementia-like symptoms might prefer themselves the diagnosis not to be one of dementia. For example, a subtle change in personality could be a ‘mid life crisis’, but it might be as politically offensive to suggest this soon for danger of being bundled with dementia symptoms being misattributed as ‘normal ageing’.

The irony is that, while medical professionals cannot offend the key medical ethical principle of ethics, if persons have full capacity as far as the law is concerned (but have dementia-like symptoms), in the form of ‘coercive behaviour’, access to care or cure could in future decades come in a rather personalised form, whether this is personalised medicine or a personal-health budget.

References

Bamford C, Lamont S, Eccles M, Robinson L, May C, Bond J (2004) Disclosing a diagnosis of dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 19(2): 151–69.

Bouckaert F, van den Bosch S (2005) Attitudes of family members towards disclosing diagnosis of dementia. International Psychogeriatrics. 17, Suppl 2, 216.

Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Buckinghamshire: Open University

Press.

Laakkonen M, Raivio M, Eloniemi-Sulkava U et al (2008) How do elderly spouse care givers of people with Alzheimer disease experience the disclosure of dementia diagnosis and subsequent care? Journal of Medical Ethics. 34, 6, 427-430.

Lin K, Liao Y, Wang P et al (2005) Family members favor disclosing the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics. 17, 4, 679-688.

Pucci E, Belardinelli N, Borsetti G et al (2003) Relatives’ attitudes towards informing patients about the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Medical Ethics. 29, 1, 51-54.

Robinson L, Gemski A, Abley C et al (2011) The transition to dementia–individual and family experiences of receiving a diagnosis: a review. Int Psychogeriatr 23(7): 1026–43

Shimizu M, Raicher I, Takahashi D et al (2008) Disclosure of the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: caregivers’ opinions in a Brazilian sample. Arquivos de Neuro-psiquiatria. 66, 3B, 625-630.

After New Labour, does Russell Brand have a point?

“It’s not up to Tony Blair to rename my party to ‘New Labour'”.

And thus spake Tony Benn.

With nearly 10 million “hits”, it’s beyond reasonable doubt that the interview between Jeremy Paxman and Russell Brand has been an internet viral sensation. It’s appreciated that, despite successes as the national minimum wage, Blair’s government was ideologically of ‘no fixed abode’, and the “clause 4 moment” can be interpreted as a symbol of the rejection of socialism (akin to Hugh Gaitskell).

Jeremy Paxman himself has said publicly that he is not particularly drawn by any political party, and about three and a half years ago the popular Labour blogger, Sunny Hundal, started an initiative to recapture “a million lost votes”.

At around the time, Peter Kellner did a tour of the conferences circuit explaining how people had curiously become detached from “the political process”. The backdrop to this is that the political process produces one leg of the ‘One Labour tripos’, the other two legs being the ‘one nation economy’ and ‘one nation society’.

Various cogent explanations were offered for this ‘democratic deficit’ in England, but curiously not high on the list was the finding that this Coalition kept on introducing statutory instruments which had not been clearly signposted in either of their two manifestos (sic). One glaring example, apart from tuition fees of course, is the Health and Social Care Act (2012).

There is no doubt that Russell Brand’s viewpoint, whilst appearing somewhat self-exhibitionist, is potentially very engaging. However, Brand’s conclusion of not bothering voting appears at first blush to be completely at odds with what Tony Benn has been arguing for ages. That’s if you don’t factor in the possibility of a Lib-Lab coalition, with our unamended boundary changes.

Tony Benn is of course not the font of all knowledge, but he is an incredibly wise man whom is the target of much affection by modern day socialists. Benn has long argued that ‘democratic socialists’ often cannot buy influence by donating lots of money to multinational corporates, but they can exert influence their democratic vote. Rather than being Brand’s ‘lost cause’ or spoilt ballot paper, in Benn’s Brave New World a vote means hope.

And indeed logically any vote against decades of English policy designed to transfer resources from the State to the shareholder dividends of private limited companies and plcs, otherwise known as “privatisation”, fits the bill.

Also, if it’s the case that the Lobbying Bill has a parliamentary intention of strangling at birth trade union activity rather than the private sector companies wishing to ‘rent seek’ in a new liberalised NHS, Benn’s desire for us socialists to exercise our vote could not have come at a better time.

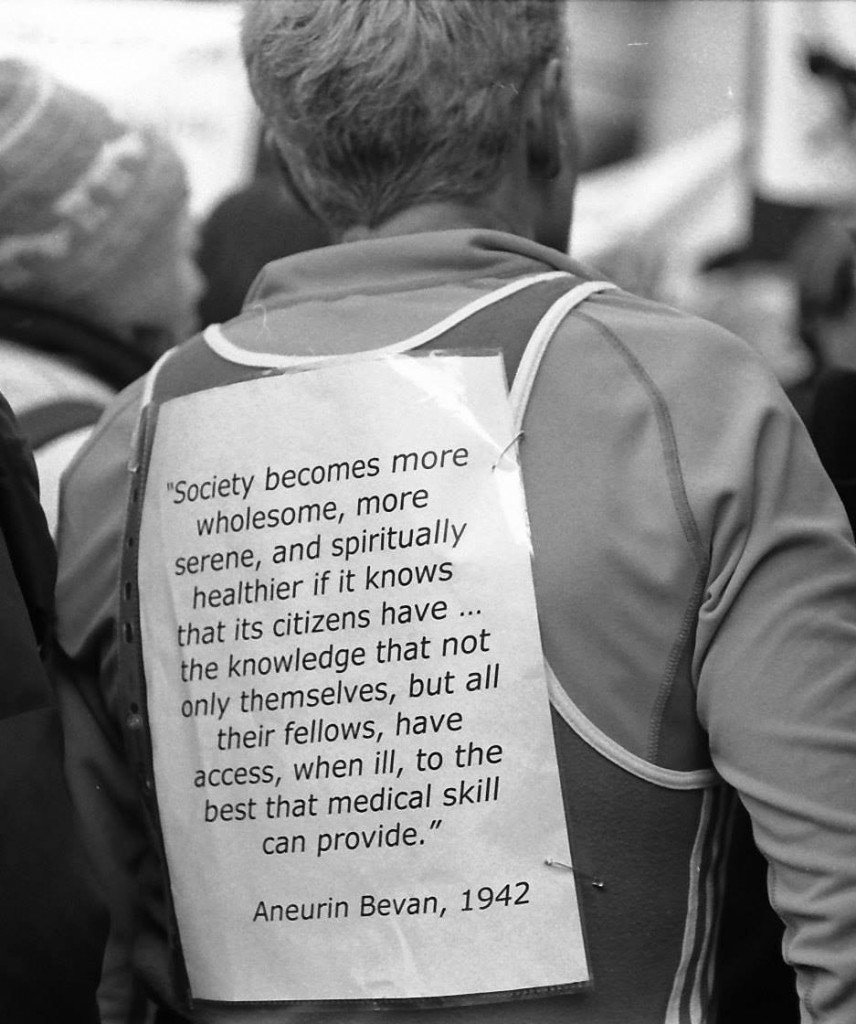

The question is of course: which party should I vote for which has the best chances of delivering a NHS based on reciprocity, solidarity, equality, cooperation, collaboration and social justice (otherwise known as socialism)? There’s an argument that true “believers” of the NHS might vote Labour (as the party which implemented the NHS under Clement Attlee’s Prime Ministership with Aneurin Bevan as health minister).

You could ‘hold your nose’ and vote Labour, as Professor Ray Tallis put it at the book launch of ‘SOS NHS’ at the Owl Bookshop in Kentish Town, or you could, on the other hand vote for one of the other alternatives, Greens or NHS Action Party. At the end of the day Benn, I’m sure, would endorse the idea that you should produce a vote most likely to produce your preferred option in the real world? But which party represents best how you feel?

If you’re faced with a choice between the Liberal Democrats and Tories, it might be tempting to vote Liberal Democrat. However, since the Liberal Democrat Party have ditched the “social and” part of the “social and liberal democrat party”, you might end up delivering a Liberal Democrat vote for a liberal part of a neoliberal Lab-Lib coalition on May 8th 2015, which is more than capable of delivering a neoliberal rather than socialist agenda. So it might not be worth voting at all, than to vote Liberal Democrat.

And the anger against Labour, particularly since the days of New Labour, is still very real. After New Labour, does Russell Brand have a point? But Andy Burnham MP emphasises categorically that times have changed: i.e. he’s repealing the Health and Social Care Act (2012), and “rejecting the market”.

As they say, the choice is yours.

Housing: one of the forgotten social determinants of health and wellbeing for persons with dementia?

The way the ‘G8 dementia’ summit was articulated by politicians and the media was that we are on a ‘war footing’ against dementia, with military metaphors aplenty like ‘battle’ and ‘fight’. After the Second World War, the Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee gave Aneurin Bevan responsibility for two tremendously sensitive posts: health and housing. Housing was crying out for attention. As a result of the war, Britain had several million bomb damaged houses in urgent need of attention and the public had been expecting the establishment of a national health service since the Beveridge report recommended one in 1942. Housing remains a huge issue in policy directions to improve the health and wellbeing of those 800,000 (or so) living with dementia in the UK.

In public health there is a growing acceptance that health is determined not merely by behavioural, biological and genetic factors, but also by a range of economic, environmental and social determinants. A safe environment, adequate income, meaningful roles in society, secure housing, higher level of education and social support within communities are associated with better health and wellbeing. It is these determinants that are generally known as the “social determinants of health”. Adequate housing means safe, secure and affordable shelter. Housing also provides the place where we connect with the wider community through education, employment, and community networks. Health inequalities are the ‘differences in health status or in the distribution of health determinants between different population groups’. Those differences are inequitable when they can be determined as being unfair or avoidable. The social determinants of health are the collective set of conditions in which people are born, grow up, live and work. These include housing, education, financial security, and the built environment as well as the health system. So unsurprisingly housing is critical for living well with dementia.

There is evidence of marked differences in health and social service use between old people with and without dementia. The hundreds of dementia diagnoses probably comprise the most important predictor of long-term care among old people. In a six-year follow up-study in Finland, 70% of women with dementia and 55% of men with dementia were institutionalised. The research evidence on hospital use is somewhat contradictory: some studies indicate that people with dementia are more likely, and others that they are less likely to be hospitalised than those without dementia. Hospital stays tend to be longer for people with dementia, and certainly constitute a large proportion of admissions ultimately in the elderly in hospital care.

Housing problems that impact on health can arise for five main reasons:

- housing is not appropriately designed

- housing is poorly located

- housing is not secure

- housing is not affordable

- housing cannot be accessed at all.

Design for dementia is important because there are very substantial numbers of people with dementia living in every type of housing, and the numbers are increasing. It provides an exciting area in which multidisciplinary approaches can be fruitfully utilised, such as from architects, housing professions and neuroscientists. The levels of impairment experienced by different people will vary greatly. Some will be at the very early stages of dementia, and may not have even had a diagnosis. The issue of addressing “the diagnosis gap” is currently a powerful force within English dementia policy. Others will be seriously impaired and reliant on support from relatives or friends, perhaps supplemented by formal care at home. New housing should provide ‘lifetime’ or ‘barrier-free’ homes, embracing the principles of ‘universal design’. In keeping with this goal, the design process should address the needs of those with cognitive and behavioural impairment. Good design, many specialists feel, should begin at the inception of the project at sketch design stage.

Poor lighting can increase the incidence of hallucinations – especially if this creates lots of shadows. It is therefore important to be able to control both natural and electric lighting to prevent sharp variations in lighting levels, avoiding excessive brightness and shadowed areas. Furthermore, blinds can be useful for diffusing strong daylight, whilst for night time a simple bright central light source with carefully directed task lights are best. Many people with dementia will spend a lot of time simply looking out of the window, and if there is something to watch this can be life-enhancing. That is why it is often recommended that designers should try to ensure communal rooms have outdoor view of garden, and/or other locations where things are happening, e.g. a car park. Of course, expert opinions on such matters will vary, but it is a hallmark of an intelligent society that we can think about what could work best for people living with dementia. For many people, getting outside is possible and may be very important.

Prof June Andrews at Stirling, in “Dementia: finding housing solutions” (May 2013), describes that two-thirds of people with dementia live in their own homes or specialist housing, while one-third live in care homes. Most people with dementia say they would prefer to stay in their own home for as long as possible. Despite half of those who live in their own home living alone, the home can be the best place for someone to manage the consequences of dementia, particularly if accessible and adaptable housing to aid independent living. Adaptations, telecare, ambient assisted living and smart homes remain powerful constructs in English policy, reflected in a considerable R&D budget spend at EU level.

It is certainly an ambition for people with dementia to live independently and have access to support and advice services if they are diagnosed promptly. Many reach out to people living with dementia in the wider community, providing services such as floating support, assessment and delivery of adaptations and housing advice. The concept of a ‘dementia friendly community’ is indeed a wide-ranging one, but is not confined to a rather narrow scope of companies and corporations acting in such a way to be dementia-friendly to secure competitive advantage. It is hypothesised that dementia friendly communities will become one day in the planning and organisation of shared care in health and social care locally. When staff are equipped with the necessary skills, and there is continued investment in services, housing providers and home improvement agencies are able to assist with a wide range of housing choices for individuals with dementia. This includes making homes more accessible or more dementia-friendly or helping with moves to specialist housing. These organisations are also often able to help with day-to-day tasks such as shopping, household chores and organising domestic bills.

As an example, the Notting Hill Housing Trust in London has developed a dementia strategy, which sets out ways to raise awareness of dementia and encourage residents to seek help. The strategy has ensured their members of staff are informed about potential signs of dementia, which has led to innovation in practice and service delivery. Core to the strategy is a group of dementia champions who challenge colleagues and promote best practice. Housing organisations overall have a very good track record of providing specialist housing and delivering services that are designed to improve health and wellbeing, prevent falls and other accidents in the home and promote independence. Falls are of course hugely significant in the elderly, as individuals with osteoporosis in poor lighting conditions are particularly susceptible to hip fractures (which can lead to protracted hospitalisation). These housing services have been proven to prevent admission and readmission to hospital, allow rehabilitation after an accident or illness, delay the need for intensive care services and reduce the likelihood of emergency admissions.

One case study of an individual with dementia being supported to live independently in Extra Care housing highlighted savings of up to £17,222 a year to health and social care budgets. Housing organisations have also introduced assistive technology to ensure that people with dementia are able to stay independent and in familiar home environments. The report “”Extra Care” Housing and People with Dementia: A scoping review of the literature 1998-2008, Housing 21 (2009), on behalf of the Housing and Dementia Research Consortium with funding from Joseph Rowntree Foundation” by Rachael Dutton highlights the positive finding that there is mounting evidence that people with dementia living in ECH can have a good quality of life. However, the report also mentions“that some tenants with dementia can be at risk of loneliness, social isolation and discrimination.” Extra care can offer an effective alternative to residential care, and can delay or prevent the need for a move to nursing care. However, while many people with dementia have been able to remain in extra care housing until the end of their lives, “enabling all tenants, with or without dementia, to remain in place through to the end of their lives in extra care housing is not usually possible”.

Telecare solutions are a proven alternative to institutionalisation for people with dementia, helping individuals to retain independence and dignity and assisting their carers who might be unpaid family members, careworkers, or others. A range of sensors can be installed in the home, to support existing social care services, by managing environmental risks. These sensors include a natural gas detector, carbon monoxide detector, flood detector, temperature extremes sensor, bed occupancy sensor and property exit sensor. Should a sensor be activated, an alert is sent either to a monitoring centre or a nominated carer. Telecare supports both safety in the home and security outside the home – where 60% of people with dementia experience the risk of ‘wandering’ dangers. Dementia can be distressing for carers, as it places them under immense pressure to help. This leads to the often hidden problem of carers suffering psychologically and financially themselves. Telecare can potentially help relieve some of this pressure – enabling carers to take a well-earned break, secure in the knowledge that they will be contacted immediately if needed. Technology can also help staff to provide a safe environment for someone through flood detection, gas shut-off systems, pagers, and medication alerts.

As a frontline service, all housing professionals work with people who have dementia, most likely in the earliest, sometimes undiagnosed, stage but also as the illness progresses. Housing professionals will also be involved where a person with dementia may be able to return home after a period in a health or social care setting following a period of crisis. Inevitably, national policy also emphasises the need for a timely diagnosis to be able to anticipate or prevent “crises”. There are therefore housing staff who work with tenants who would benefit from an understanding of what the dementias are, how to identify the features, and what to do next in terms of referral and/or discussion with health or social work colleagues. However, there is no doubt that the approach of joining up health, wellbeing and housing is just the tip of the iceberg; there needs to be better awareness of the dementias generally, attention and resources for dementia-friendly communities, and a real attention to detail (such as design features and innovations of the home). But this is a marathon, rather than a sprint.

Does electronic surveillance of persons with dementia conflict with personhood?

Families, friends, and carers of people with dementia may be faced at some time with the problem of what to do if the person begins to wander. Wandering is quite common amongst people with dementia, and can be very worrying for those concerned for their safety and living well. The problem of wandering in dementia is not trivial. It causes stress to carers, referrals to psychiatric services and hospital admissions, problems in the hospital environment, and an unknown number of deaths.

The last Labour government developed a reputation for being authoritarian in the domain of civil liberties, reaching a peak, arguably, with its legislation for terrorists for detention without trial. Governments of all shades have at some point or other wished to stamp their liberal or libertarian credentials, and indeed in relation to the free market. For example, an outsourcing company within the lifetime of this government got into trouble over allegations to do with prisoner tagging.

Different companies have been pitching their products – tiny cameras, wearable sensors, connectivity services – mainly at the US and other rich countries where abductions and violent crime are mercifully rare. Google recently, to much media attention, launched with great fanfare its ‘Google glasses’. Indeed, a Scottish friend of mine recently logged onto her Facebook in Bilbao in Spain, and Facebook cunningly producing a sponsored advert for a hotel in Bilboa. When you make a tweet, you have an option of activating the ‘location detector’ of your tweet. This article is not about terrorism or the use of smart apps to book hotels, but the point is merely that a plethora of converging evidence might suggest that a technology explosion may be going hand in hand with a surveillance culture, and it is perhaps no big surprise that this is also having an effect on dementia care.

I asked Alex Andreou, who has written with remarkable authority and passion about his own mother living with dementia in the Guardian newspaper, what he thought of the general issue of electronic surveillance of persons with dementia?

“I would welcome it. Terrifying when I see reports about people lost.”

When I reassured Alex that I would not mention this name, Alex said, “I don’t mind if you do.”

Sussex Police has been trialling the scheme at a cost of £400 a month, and hopes it will save the force thousands of pounds by avoiding call-outs which can take up a lot of police officers’ time and can involve the use of search helicopters. A number of local authorities are already using similar devices to track sufferers, but this is believed to be the first time a police force has taken on such a scheme in May 2013. If the trial is successful, there are ambitions to roll it out across the county to a much larger population. The idea is that people with dementia can wear the tracking device around their neck, clipped to a belt or on a set of house keys. It works through a Global Positioning System (GPS) – a space-based satellite navigation system that is used by ‘sat-navs’ in vehicles. It is linked to a 24/7 response service which the wearer can call at a press of a button. The device is called “MindMe”, and family and friends can log into the system whenever they like to find out where the person is.

It is claimed that the Police regularly have to search for missing people with dementia, and that it is genuinely heartbreaking to see the torment that their families are put through and to see the impact it has on the person with dementia when they are found. A £15 (€18; $23) pair of transmitters would, for example, sound an alarm if the person gets separated. GPS trackers not intended as a general panacea, but they do mean that patients can be found more quickly. This is thought to be useful for several reasons. Firstly, rapid recovery reduces risk. Typically, carers delay calling for help, wanting to avoid involving the police if possible. Half of all people with dementia who are missing for more than 24 hours can die or become seriously injured. However, 40% of those with dementia get lost at some point, and about 5% get lost repeatedly. It is this 5% who are the most obvious candidates for a tracker. The first episode of getting lost is usually not predicted, and is often followed by restrictions on freedom and increased observation, reducing the perceived need for a device.

On November 11th 2013, Norman McNamara, a campaigner for awareness of the dementias himself who himself is living with a dementia, announced that, that Ostrich Care would be making available free GPS trackers to all persons who are diagnosed with dementia, and to registered carers (in the UK, not uniquely to the Torbay area.) A monthly ‘maintenance fee’ still has been made though. The info from Ostrich Care is here (ht: Jane Moore).

But in reality there is no right answer. The situation is complex. Decisions about limiting a person’s liberty should remain a matter of ethical concern even when technology finally makes the practical management of wandering easier. This approach has as its backdrop evolving body of work on technology and dementia, known as “assistive technology”, where collaboration and engagement with “users” has been a guiding principle. The earlier literature on electronic surveillance monitoring pointed out that the technique could be associated with objectification, infantilisation, and disempowerment, which are negative phenomena. The acceptability of surveillance monitoring has generally been researched among formal and informal carers only, with the views of those living with dementia curiously under-represented.

The whole issue can raise strong emotions. Dot Gibson, general secretary of the National Pensioners Convention, has been reported as feeling that the Sussex Police scheme is “inhumane”, “barbaric” and flouts fundamental human rights. This criticism has been bundled with a general criticism of the care system, with Gibson adding, “This is trying to solve a human problem with technology”.

According to Gibson:

“Using electronic tags on dementia sufferers raises very important issues about the individual’s human rights. They haven’t committed any crime – they’ve just grown old. This is just about saving money rather than treating people with dignity. Rather than tagging people we need better social care out in the community. Dementia patients need human interaction not tagging.”

In terms of medical ethics, “autonomy” relates to self governance or personal control. One of the main aims of implementing these surveillance monitoring devices is the promotion of increased independence. Most carers, whether relatives or paid staff, want the best for the person they support. Alongside doctors’ duties of beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice, respect for patient autonomy is invoked as a cardinal principle. The legal courts in various jurisdictions have confirmed the principle of respect for patient autonomy in the language of rights of self-determination. This is not merely viewed as a a rejection of a paternalistic tradition of ‘doctor knows best’, but includes differing philosophical positions including those of Kant.

There are a number of possible reasons why a person with dementia might wander, and this is related to which parts of the mind or brain are affected at any particular time. Here is yet another example where it is unhelpful to think of ‘dementia’ as one big homogeneous group. There are hundreds of different causes of dementia, and this might impact on why a person with dementia wanders. However, any patient living with dementia can of course become acutely confused, just like any other person (particularly in the elderly age group due to some underlying infection, for example.) Various important causes include a changed environment, excess energy, searching for the past, expressions of boredom, where it might be difficult to establish an underlying ‘medical cause’.

Dementia of the Alzheimer type is the most common type of dementia worldwide. Memory problems are the hallmark of dementia of Alzheimer type. Indeed, wandering may be due to a loss of short-tem memory. A person may set off to go to the shop or a friend’s house, and then forget where they were going or why. Or they forget that their partner has told them that they were going out for a while and set off in search of them. In another type of dementia known as Lewy Body dementia, visual hallucinations can occur: in other words, seeing things which aren’t there. An inability to distinguish hallucinations from reality may cause the person to respond to something that they dreamed, thinking that this has happened in real life. Lewy Body dementia tends to affect the younger age group (by younger, I mean below the age of 60).

In advanced dementia, whatever the cause of dementia, people can lose their regular ‘body clock’ or circadian rhythm. People with dementia may suffer from insomnia, or wake in the early hours and become disoriented. They may think it is daytime and decide to go for a walk. Poor eyesight or hearing loss may mean shadows or night sounds become confusing and distressing. Also, in advanced dementia, walking may actually ease discomfort, so it is important to find out if there is any physical problem or medical condition and try to deal with it. Tight clothing, excessive heat or needing to find a toilet can all cause problems. Also, changes that have occurred in the brain may cause a feeling of restlessness and anxiety. Agitation can cause some people to pace up and down or to wander off with no apparent purpose. They may fail to recognise their own home, and insist on leaving.

Some caregivers appear to like the idea of electronic tracking devices if these can ensure that the wanderer is found more swiftly. Some argue that for, the sake of safety, a slight loss of liberty might be a price worth paying. In the case of someone with moderate to severe dementia who wanders, electronic surveillance monitoring arguably satisfies an ethical principle and decreases stigma. Being lost and half dressed in the middle of the night near a dual carriageway to any reasonable unlooker is hugely stigmatising, and electronic surveillance monitoring could avoid this. However, there is a concern that wandering as a behaviour of the dementias, like many aspects, is generally becoming overly medicalised, or turned into a medical problem. The inevitability of this is to turn it into a medical problem in need of a medical solution. This in turn potentially legitimates social control efforts in the name of ‘protecting’ wanderers.

Social control through the medical gaze encourages an environment of pharmacological surveillance and physical confinement. We all know of the dangers of the approach of the “chemical cosh”. Neuroleptic drugs have harmful side effects and show only modest efficacy in managing some behavioural problems in dementia. Physical restraints, such as safety belts and bedrails, are used in nursing homes all over the world, with a prevalence somewhere averaging around 50%. There is growing awareness that the use of these means can have significant psychological and physical disadvantages, such as increased cognitive decline and decreased mobility and has even led to death in some cases. Therefore, it is argued legitimately that the use of physical restraints should be diminished. Counsel and Care’s famous publication ‘The Right to Take Risks’ (1993) lists at least twenty forms of restraint commonly used at present, ranging from literally tying someone down to the use of sedatives, locks, glass panels in doors, threats and poverty. Despite the negative press associated with electronic surveillance monitoring devices in some quarters then, this new technology, developed and perfected as a result of its uses in prisoner tagging, may offer somehope of a more humane solution to a difficult problem. Here, language is crucial, as “surveillance monitoring” is a preferable term to “tagging”, as it is completely objectionable to use language for people with dementia normally reserved for criminals. You cannot be ‘convicted’ of having a diagnosis of dementia. Whilst some ideologically might feel nervous of a somewhat libertarian-facing solution, the risks and restrictions of alternatives to surveillance monitoring, should perhaps be borne in mind.

Over the last decade, a new ethos in the management of wandering has evolved with a move towards promotion of safe walking, rather than the prevention of wandering, in order to balance a person with dementia’s need for autonomy with the need to minimise risk. Other non-pharmacological approaches include: behavioural approaches; carer interventions; exercise; music therapy; sensory therapies (aromatherapy, multi-sensory environment); environmental designs and subjective barriers (visual modifications that may be interpreted as a barrier but are not physically so). Evidence on the effectiveness and acceptability of the above interventions is limited. The availability of all alternatives will frequently depend on resources, attitudes and policies of health professionals, institutions and governments, and the precise legislative and regulatory framework. For example, in the Netherlands, the Health Care Inspectorate promotes the use of surveillance technology as a way to diminish the use of more severe means of restricting freedom. In 2009, already 91% of the nursing homes were using some kind of surveillance technology in the care for people with dementia. In most developed countries, the legislation regarding the use of physical restraints is based on, among other things, guidelines of the United Nations and the World Health Organization and the European Convention on Human Rights (Council of Europe, 1950; General Assembly of the United Nations, 1948; World Health Organization, 2005).

Although surveillance monitoring might increase liberty in some senses, it has the potential to decrease autonomy and tracking devices might settle the anxieties of others without attending to the needs of the person with dementia. There are considerations from medical law and medical ethics too on the place of the family. Where the adult patient is unable to consent, both medical ethics and law allow for consultation with relatives. Indeed, consultation with the family is the default position in cases of adult patient incompetence. The general tradition of ethics can be denoted through primary concern with individuals; in fact, medicine’s traditions have a tendency to be individualistic. It could be that ‘taking friends and families seriously’ challenges that individualistic approach. For illustration, the doctor-patient relationship is structured in a manner similar to a contract between two individuals, and the doctor has a duty to the person/patient. Contrary to individualist perceptions of autonomy, “communitarians” acknowledge the significance of the person’s relations. This is of course particularly relevant if one wishes to pursue in English policy and elsewhere the notion of “dementia friendly communities”. If it can be mooted that liberals focus on what separates people from one another, communitarians see persons as fundamentally attached to each other. For such an approach to work, those advising concerned relatives need to be trained in not only dementia care but also in understanding and negotiating the different ethical perspectives of carers and professionals.

This is important so that professionals do not seem to be assume some high moral ground of civil libertarianism, as well as to allow recognition that our autonomy is exercised in the embrace of others. So in my opinion the use of surveillance technology, as either an infringement of human rights or as contrary to human dignity, as it reduces or infringes privacy and removes personhood, is only a small part of the issue. There is a danger that resorting to technology in general might result in a reduction in the essential human contact between caregivers and residents and could lead to a further decrease in staff in long-term care facilities. However, if this is a known risk, this can be mitigated against, and adoption of electronic surveillance monitoring might led to the evolution of a more secure environment (thereby reducing caregiver stress), but also increase liberty and dignity when compared with forms of physical restraint. The ‘threat to personhood’ is an important consideration, and the law itself regarding mental capacity as currently drafted in the English jurisdiction could indeed be too a blunt weapon. However, policy in general has been driving to empowering persons with dementia to have more choice and control than previously, and this policy driver is not at all insignificant.

In “Big Dementia”, who cares about dementia carers?

Without the work of unpaid carers, the formal care system would be likely to collapse. Some feel that the State gets a “very good deal” out of this current system. The ongoing support from unpaid carers will be a particular issue for the care system in the future, as changing demographic patterns, shifts in family composition, labour force participation and increased geographical mobility will affect the availability of the unpaid care workforce. There are also significant issues emerging in care work.