Is doing “more with less” in dementia becoming “a lot more with virtually nothing”?

The “doing more with less” mantra of course very popular as a solution to the impending doom of having to treat the old fatties with a burgeoning technology budget. Re-engineering the health system has become a hobby of thinktankers, in the best spirit of the blind watchmaker. But policy wonks are still unable to escape from the fact that the NHS is not a widget factory. The management school of Frederick Taylor is totally unfit for purpose in considering outcomes rather than outputs. As national policy moves steathily towards promoting wellbeing, particularly in long term conditions, the question becomes, “what is a good outcome for a person with dementia?” Econometrics, and people in big corporates, will immediately point to costs, such as the financial cost of ‘unplanned admissions’. However, the “tide is turning” on all that. People are becoming interested in empowering people with dementia to lead fulfilling lives, building on what they can do. It is however inherently undermined by people wishing to abuse the system, such as large companies returning massive shareholder value and paying their staff pittance on zero-hours contracts. Everyone also knows the system only can survive through the large army of unpaid family caregivers.

At a time when Don Berwick was in fact Donald M Berwick president of the “Institute for Healthcare Improvement”, before he became ‘even more famous’, he published, “Measuring NHS productivity: How much health for the pound, not how many events for the pound” in the BMJ on Saturday 30 April 2005. Berwick reported that the ONS had recently concluded that NHS productivity had declined by 3-8% (depending on the method of calculation) between 1995 and 2003. This had led Berwick cheekily to ask, and most pertinently to ask, ““Production of what?” is the key question here. If we ask the wrong question the answer may lead us to the wrong policy conclusion.”

Berwick noticed that the method used thus far was fundamentally flawed.

“it does not assess improvement in the mix of these so called outputs, such as when innovations in care allow patients to be treated successfully in outpatient settings rather than in the hospital. To its credit, the ONS notes carefully that “the output estimates do not capture quality change.” Its interpreters need to show equal caution.”

Berwick concluded,

“The people of the UK should be not asking, “How many events for the pound?” but rather, “How much health for the pound?” At least, that is what they should ask if they desire an NHS that can keep them healthy and safe at an affordable price for as long as is feasible.”

Wind on five years, and John Appleby, Chris Ham, Candace Imison and Mark Jennings gave birth to “Improving NHS productivity: More with the same not more of the same” from the King’s Fund on 21st July 2010. You can view it from here, if you wish. Efficiency, in true Frederick Taylor, was the name of the game again.

“As the evidence brought together here shows, there is huge scope for using existing expenditure more efficiently, in relation to both support and back-office costs, and particularly variations in clinical practice and redesigning care pathways. It should be noted that the actual sums identified as potential savings may have already been partly achieved by the programmes listed, and so the figures should be interpreted as an indication of the scale of potential savings rather than an absolute figure.”

Of course, the language of efficiency is totally laughable in the private sector with finding profit in repeated work and unnecessarily transactions. As the NHS lives in denial that its budget is not being squeezed, as £20bn is returned to the Treasury from “efficiency savings”, pursuing efficiency has been ‘a means to an end’, and, together with the zest for austerity, perpetuates the notion that NHS needs to dramatically cut budgets, reduce systematically services for patients and sack staff.

In his 2008/9 Annual Report, Sir David Nicholson prepared the NHS to plan ‘on the assumption that we will need to release unprecedented levels of efficiency savings between 2011 and 2014 – between £15 billion and £20 billion across the service over the three years’. These figures were based on analysis by the Department of Health, which assumed zero real growth from 2011/12 to 2013/14 in actual funding for the NHS in England. Given the state of the handling of the economy by the current Government, this was in fact quite a good assumption. It set this against spending that would be required to meet – as Nicholson reported (Health Select Committee 2010) – demographic changes, upward trends in historic demand for care, additional costs of guidance from NICE, changes in workforce and pay, and the costs of implementing government a £2.4bn non-“top down reorganisation” policy. Hence, the resultant ‘gap’ between actual and required funding of between £15 billion and £20 billion by 2013/14. Talking optimistically that is..

For dementia, there are other factors at play. With unified integrated budgets, or “whole person care”, it might be difficult to identify where the cutbacks are, as the figures merge into a morasse of confusion. Slimming the State might give a blank cheque under such a construct completely to annihilate social care. And against this background “self-care” – helping patients to better manage their own condition – has been promoted as being effective in reducing emergency admissions, including the use of care planning. At worst, “self care” is a figment of the Big Society which is a turkey which never flew.

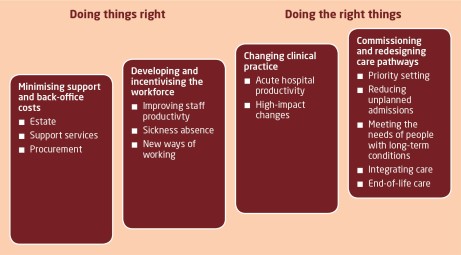

So in that report from the Kings Fund various leadership and management devices are identified in relation to a productivity squeeze, of relevance to “the funding gap”:

A practical example of the benefits of integration along the pathway of care can be seen in Torbay, where health and social care integration has had a measurable impact on the use of hospitals. Torbay has established five integrated health and social care teams for older people, organised in localities aligned with general practices. Health and social care co-ordinators liaise with users and families and with other members of the team in arranging the care and support that is needed. Budgets are pooled and can be used by team members to commission whatever care is needed.

And – if productivity for dementia is extremely difficult to quantify, especially if you’re doing “more with less”, what about the general economy? According to NEF, recent estimates of productivity have told a familiar story: output per hour worked fell by 0.3% over the middle part of 2013. This means whatever economic growth occurred over the last year was not the result of people working better, or more efficiently. It was the result of an increase in the total number of hours worked. Productivity, over the whole year, barely improved. Roll over Taylor.

Labour productivity, the amount of economic output each worker generates per hour, fell sharply in the recession and has remained very weak. Employers hung on to workers when output fell and hired more people when the economy was stagnant. Productivity levels have remained relatively unchanged since the beginning of 2008. The difference between this and the three previous recessions is stark. And that is “the productivity puzzle”. ONS research has concluded that there is no single factor that provides an explanation, but identifies several that may have contributed.

Of particular scrutiny from economists has been something which has been enigmatically called “the changing nature of the workforce”. Firms have less need to fire people if pay rises are modest or if they are willing to work fewer hours. It is called “labour hoarding”, where employers hang on to more workers than they need in a downturn, so that when there is a recovery they can respond quickly, without incurring the costs of hiring and training new people. In a paper published published by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, researchers found many factors affecting productivity. They foud little evidence that the overall fall has been caused by labour hoarding, the demise of financial services or changes in workforce composition. Instead, we conclude that the key contributing factors are likely to be low real wages, low business investment and a misallocation of capital. But there’s always been one particularly attractive theory: “flexible” labour markets have been proved to be very effective in delivering part-time and temporary work, at low cost to employers. This is where market forces can lead to exploitation.

A “zero-hour contract” is a contract of employment used in the UK which, while meeting the terms of the Employment Rights Act 1996 by providing a written statement of the terms and conditions of employment, contains provisions which create an ‘on call’ arrangement between employer and employee. It does not oblige the employer to provide work for the employee.The employee agrees to be available for work as and when required, so that no particular number of hours or times of work are specified. The employee is expected to be on call and receives compensation only for hours worked. And they are popular – one survey suggests that up to 5.5m people are now working on a zero hours basis. Meanwhile, underemployment – those who would like to work more hours, but cannot – is at record levels. When faced with collapsing markets in the recession, employers – rather than reducing the number of people in work – effectively cut wages and hours of those working.

Doesn’t this sound perfect for addressing the NHS funding gap in dementia?

Reviewed by Roger Kline, several reports have made clear that recent changes in employment practices are undermining safe and effective care outside hospitals. In particular, according to Skills for Care, 307,000 social care workers are now employed on zero-hours contracts under which staff have no guaranteed hours (or income) and travel time is unpaid. This accounts for one in five of all professionals in this sector and the numbers are growing rapidly. Also, it is argued that “personalisation” has led to a growth of a section of the homecare workforce with virtually no employment rights at all – often on quasi self-employed terms – as well as raising serious questions about support, quality, training and supervision. All parties have been keen to pursue personal health budgets. It may be a coincidence that all parties agree on the need for the “efficiency savings”.

So the parties are largely singing from the same hymn sheet, and it is hard to know whether the think tanks have led to a discussion which airbrushes zero-hours contracts and unpaid family caregivers in dementia. In discussions of integrated care from think tanks, albeit in various guises such as “Making best use of the Better Care Fund” from the King’s Fund or “Whole person care” from the Fabian Society, there is a distinct unease about talking about the army of unpaid family caregivers, without whom many agree the care system would collapse, or those low-paid carers on zero-hours contracts. Converging evidence from the macroscopic picture of our economy, in the form of the ‘productivity puzzle’, and the landscape of social care for dementia paints in fact quite a grim picture of legitimising a solution to “the funding gap”.

This solution implemented has not in fact “doing more with less”. It’s been “doing a lot with virtually nothing”. And whatever your precise definition of ‘productivity’ for these workers, it is clear that many are at breaking point themselves under consider psychological and financial pressures themselves. Shame on no-one for discussing this with the general public.

Exploitation of carers should not be the solution for solving “the funding gap”.

The sting in NHS data sharing is in making insurance contracts void

Even Google gave up on their central database for health information called “Google Health“. Whilst few things are as certain as death and taxes, it is fairly certain that there is big money in big data. Lord Shutt of Greetland, Chair of the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust Ltd. warned, in a foreword on a recent report on “the database state“, that the problem is huge, and as a society we must face up to formidable challenges. There has always been a tough balance in the law between balancing individual rights of privacy and freedom, with the State’s rights of national policy of health and security, for example. Whatever ideological position the Liberal Democrats eventually settle on, it is striking that a Conservative Prime Minister should actually advocate nationalising something.

It is unsurprising that Big Pharma would have welcomed the move. Andrew Witty, the chief executive of GlaxoSmithKline, stated to the Sunday Telegraph he welcomed the data-sharing initiative: “Any action the government takes to improve the environment in this country for life science across these activities is welcome.” The Autumn Statement (2011) had indeed signposted this. It might seem paradoxical that the Department of Health at this time wishes to embark on an initiative to make the NHS “paperless”, at a time when a reorganisation, estimated at £3bn, is currently underway. Patient data, essential for individual patient security, confidentiality and consent, are “rich pickings” for the private healthcare industry, which have not collectively paid to collect this information nor invest in the IT infrastructure of the NHS, but the ethical concerns are enormous. Personalised medicine, dependent on real-time patient information, is “the next big thing” emergency in the pharmaceutical industry, currently keeping stocks of companies very healthy. However, the professional code for Doctors, from the General Medical Council (“GMC”) is very clear on the regulation of patient confidentiality and privacy: this is contained within “Confidentiality” (2009), and clearly guides doctors on the conflicting balance between confidentiality and disclosure.

There are interesting reasons why the operational roll-out of the National Patient Record failed in 2006-7. It is now reported that all prescriptions, diagnoses, operations and test results will be uploaded on to central computers by the end of next year, and, by 2018, all NHS organisations will be expected to be able to share this information with other hospitals, GPs, ambulances and health trusts. Jeremy Hunt hopes local councils will sign up to similar systems, along with private care homes. As with the overall direction of travel of the NHS towards an insurance system where private companies pay “a greater part”, this blurring of the need for patient consent has been insidious.

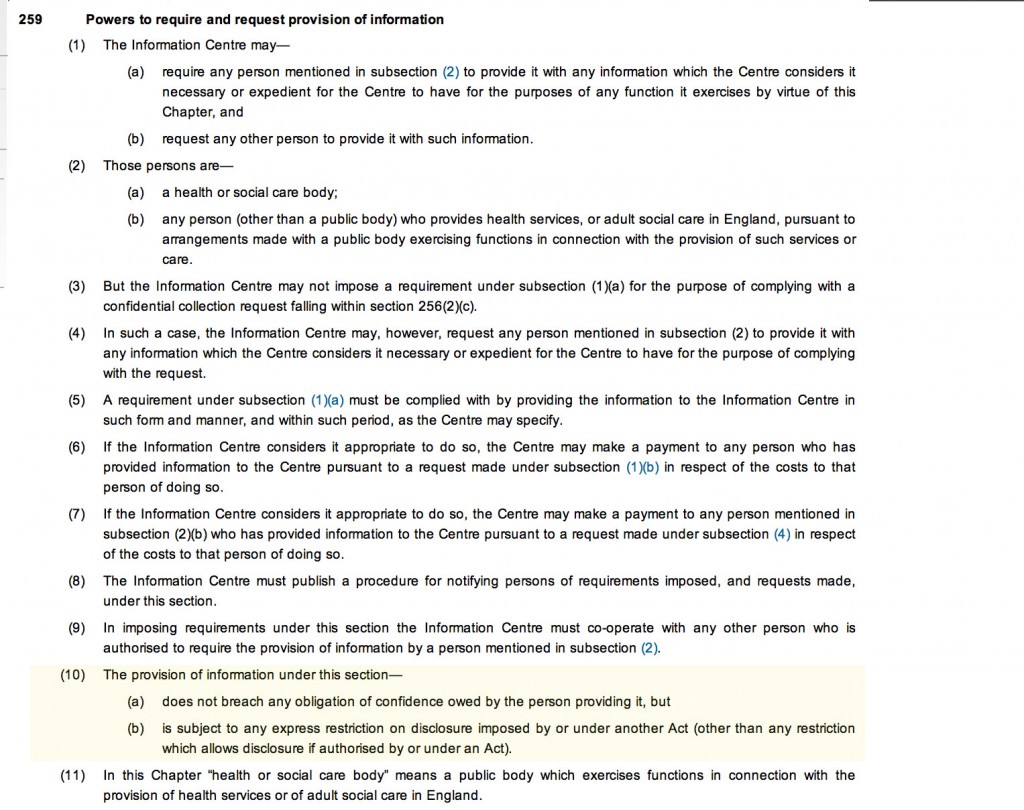

Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 (originally enacted under Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001), allows the common law duty of confidentiality to be set aside in specific circumstances where anonymised information is not sufficient and where patient consent is not practicable. For example a research study may require access to patient identifiable data to allow linkages between different datasets where the cohort is too large for consent. This would require time limited access to identifiable information where gaining consent from a large retrospective cohort would not be feasible and would require more identifiable data than would be necessary for linkage purposes. However, section 10 of the Data Protection Act (1988) currently allows a right for an individual to prevent damage or distress by data processing. This is indeed conveniently “triggered” by section 259(10) of the Health and Social Care Act (2010), i.e. “[the provision] is subject to any express restriction on disclosure imposed by or under another Act (other than any restriction which allows disclosure if authorised by or under an Act”:

The Secondary Uses Service (SUS) Programme supports the NHS and its partners by providing a single source of comprehensive data for planning, commissioning, management, research, audit, public health and “payment-by-results”, a reimbursement mechanism for acute care payments. It is critical to know whether patients maintain a right to opt out of the SUS database. It should not be the case that NHS patients are denied hospital care if they do not agree to my records being sent to SUS. Steve Nowottny in his “Editor’s Blog” for Pulse, a newspaper circulated to GPs, on 8 January 2013 outlined some important very recent developments:

“That year, Pulse ran a ‘Common Sense on IT’ campaign which highlighted a series of concerns over the consent and confidentiality safeguards in the new system.

“GPs wanted patients to have to give explicit rather than merely implied consent before records were created. Plans to use data within the records for research purposes without explicit consent had Catholic and Muslim leaders up in arms, because they feared the research could be purposes contrary to their faiths, such as abortion or stem cell research.

We revealed that celebrities, politicians and other patients whose information is regarded as sensitive would be exempted from the automatic creation of a Summary Care Record, raising questions about the system’s security. And we reported that patients who did not initially choose to opt out of the Summary Care Record would be unable to have their records subsequently deleted.

At the time, it felt as though the stories, while interesting and concerning, were somewhat theoretical. The Summary Care Record’s deployment to date had been patchy and it was far from certain it would continue. In the meantime, fewer than 1% of patients had bothered to opt out. (Now, with nearly 22 million records created and more than 41 million patients contacted, the figure stands at 1.34%).

But the news today that 4,201 patients had Summary Care Records created without them giving even implied consent – and that they will not be able to have them deleted – reignites the whole debate. Suddenly ‘what if’ scenarios have become reality.”

Tim Kelsey is the NCB’s National Director for Patients and Information – his stated aims are to put transparency and public participation at the centre of a transformation of customer service in the NHS. In a recent lecture, he quoted George Soros who said “our social institutions are imperfect, they should be open to improvement [and that] requires transparency and data“. On-line banking and e-ticketing demonstrate the power of open access to personal data in a safe, secure way – for some reason, heath data is deemed more personal that finance and travel arrangements. Data.gov.uk is an example of his vision for the future – the UK has so much medical data, not only about patients but also genomics and other bioinformatics disciplines. The law currently gives the NCB power to mandate more data flows – Kelsey apparently targets April 2014 to get outcomes-based data flows from primary and secondary care – once achieved, next step is to embrace social and specialist care. So, once the data is “freely available”, it can be made available for public participation – he is investing in a course called ‘Code for Health’, a 3 day course to learn how to develop apps. Data are essential from April 2013, there will be push for on-line interaction with GPs, to realise nationally the benefits seen in pilot areas.

So why should commissioners need access to “personal identifiable data”? It is considered that these may be “good reasons”:

- integrated care and monitoring services including outcomes and experience requires linkages across sources

- commissioning the right services for the right people requires the validation that patients belong to CCGs and have received the correct treatments

- aspects of service planning and monitoring on geographic data basis require postcodes for certain type of analysis

- understanding population and monitoring inequalities

- target support for patients and population groups at highest risk requires data from several sources linked together

- specialist commissioning is commissioned outside local areas and can require wider discussions about individual patients and their associated costs

- ensuring appropriate clinical service delivery and process requires access to records

To enable commissioning, ‘personal identifiable data’ including NHS no, DOB, Postcode data needs to flow to “data management integration centres” (“DMICs”). The DMICs need to have similar powers and controls to the Health and Social Care Act information centres to process data It was known that, in order for processing of PID at DMICs to be undertaken legally, a change in legislation would have been required.

David Cameron has stated explicitly his intention for social care to head towards a private insurance system. As stated in the transcript of the interview with Andrew Marr,

“Well the point that was being made earlier on the sofa by Nick Watt, this is a massive problem – that you know more and more people suffering from dementia and other conditions where they go into long-term care and there are catastrophic costs that lead them to have to sell their homes to pay for that care – it’s right to try and put in place a cap which will then open up an enormous insurance market, so people can insure against that sort of catastrophic loss.”

A longrunning conundrum about where there is such intense interest in ‘raising awareness of dementia’. The idea of having GPs and physicians ‘diagnose’ dementia on the basis of a screening test, without it being called ‘screening’ in name, has not been backed up with the appropriate resource allocation for dementia care elsewhere in the system, including adequate training for junior doctors and nurses crucially involved in actual dementia care. Is this and integration of care an entirely virtuous sociological problem? Integration of care at first sight seems to involve primarily avoidance of reduplication of operations, and better ‘coordinated’ care between health and social care and funding. This is not an unworthy ambition at all. It is well known that the endpoint of the Pirie and Butler “Health of Nations” blueprint for NHS privatisation has a greater rôle for the private insurance market as the endpoint, so it makes complete sense to have a fully integrated IT system which private insurers and the Big Pharma can tap into.

Lawyers will, of course, be cognisant about the added beauty of integration of clinical and financial information. One of the biggest banes of insurance markets is information asymmetry, making calculation of risk and potential payouts difficult. Insurers will argue that calculation of risk is only possible with precise information, clinical commissioning groups are merely “statutory insurance schemes”. It is a long-held belief that private insurers refuse to pay off given the slightest lack of compliance in terms and conditions, but private insurers provide that this mechanism needs to exist to protect them making unnecessary payouts. Failure to disclose medical conditions is an excellent way for private insurers to get out of “paying up”, otherwise known as rescission. Of course, this could be taking the “conspiracy theory” far too far, and these concerns about the use of “big data” otherwise than for a “public good” may be totally unfounded.

You can, nonetheless, mount an argument why the current Government wish to progress with this particular approach to private medical data. The private insurance market and Big Pharma stand to benefit massively, and their lobbying is much more sophisticated than lobbying from GPs, physicians or members of the public. The drive towards all nurses having #ipad3s and all TTOs from Foundation Doctors being sent by broadband to nursing homes may seem utterly virtuous, but there are more significant drivers to this agenda beyond reasonable doubt. On the other hand, it’s simply that healthcare policy is in fact improving for the benefit of patients.

Extremely grateful to the work of Prof Ross Anderson, Chair of Computer Security at Cambridge University, and Phil Booth @EinsteinsAttic on Twitter with whom I have had many rewarding and insightful Twitter conversations with @helliewm.

Twitter’s telling me some of you have received my book at last!

Thanks to Rhona Light (“@Hippiepig“) for giving me feedback on my book. She was the very first to receive it.

Rhona’s copy of her book arrived yesterday.

@legalaware Sorry I can’t tweet a pic as it says over memory limit but it is super. Poppy cover with CPD cert logo and forewords attrib.

— Rhona Light (@Hippiepig) January 28, 2014

@legalaware Good quality paper and very clear print. You will be pleased.

— Rhona Light (@Hippiepig) January 28, 2014

@legalaware Proper medical textbook quality x

— Rhona Light (@Hippiepig) January 28, 2014

@legalaware it is very well structured. I think that it is very well sub-headed. It is highly accessible for a non-medical person like me.

— Rhona Light (@Hippiepig) January 28, 2014

@legalaware It is very readable – your style is great and it is wonderful to read a book that is so well researched and balanced. This will

— Rhona Light (@Hippiepig) January 28, 2014

@legalaware be the standard textbook for courses. Just stunning.

— Rhona Light (@Hippiepig) January 28, 2014

Thanks also to @KateSwaffer for her supportive comments about my book.

@Hippiepig @legalaware I agree even though I’m only half way through this wonderful book

— Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer) January 28, 2014

And Rose got it too (@RoseHarwood1):

@legalaware @dementia_2014 @nursemaiden @WhoseShoes @charbhardy It’s arrived! Can’t wait to get stuck in!  x pic.twitter.com/RccxttOCQF

x pic.twitter.com/RccxttOCQF

— Rose Harwood (@RoseHarwood1) January 29, 2014

If you buy the book off Amazon, please remember not to buy it directly from them or you could be waiting 9-11 days. Here’s the link to the book on Amazon. I bought it today from “The Book Depository” as my complimentary copies hadn’t arrived. But I know it’s selling well. Yesterday it reached #3 in the UK.  And I was honoured to receive this tweet from Prof Simon Wessely, who is at the Maudsley/Institute of Psychiatry, and President-Elect of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

And I was honoured to receive this tweet from Prof Simon Wessely, who is at the Maudsley/Institute of Psychiatry, and President-Elect of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

@legalaware am impressed..looking forward to it hitting number 1 — Simon Wessely (@WesselyS) January 27, 2014

I’ll be presenting the book to 25 guests in private in Camden on Saturday 15th February 2014. This includes of course Charmaine Hardy whose poppy is on the front cover:

@piponthecommons @legalaware thanks it’s Shibley written it

— Charmaine Hardy (@charbhardy) January 29, 2014

@kgimson @ILoveLincs @legalaware thank you I’m so proud x

— Charmaine Hardy (@charbhardy) January 29, 2014

This is the book @legalaware has written with my photo on the front cover. I’m so proud pic.twitter.com/4koQ12nnq5

— Charmaine Hardy (@charbhardy) January 29, 2014

Thanks a lot to Pippa Kelly too (@piponthecommons)

@charbhardy @legalaware Congratulations to you both! Great achievement. Wonderful cause.

— Pippa Kelly (@piponthecommons) January 29, 2014

And I look forward to going out for dinner with them in the evening in Holborn.

Is the drug industry “stopping dementia in its tracks” or in actual fact “running out of steam”?

Sometimes you have to trust people to get on with things.

That’s why headlines saying fracking under homes could go ahead without permission don’t help.

And the reported assimilation of ‘caredata’ into the NHS information “borg”, without clear valid consent, is running into problems.

We cannot sign off every single decision about how each £ is spent in the ‘fight against dementia’ as it’s called. But the issues about care vs cure in dementia is running into the same problems with imbalance in information as fracking and care data. This threatens seriously to undermine trust in policy leaders supposedly working on behalf of us in tackling dementia.

The origins of the phrase “stopping dementia in its tracks” are obscure. Stopping something in its tracks may be somehow related to the phrase “running out of steam” for nineteenth century railway trains “running out of steam”, or coming to a sudden end when travelling. Is the drug industry “stopping dementia in its tracks” or in actual fact “running out of steam”?

To stop something in its tracks, nonetheless, is a popular metaphor, as it tags along with the combattive ‘war’ and ‘fight’ against dementia theme.

While there’s been a need to focus on bringing value to lives with dementia, much of the fundraising has involved painfully pointing out the costs. A study conducted by RAND Corp. for the federal government earlier in 2013 found that nearly 15% of people ages 71 or older, or about 3.8 million people, now have dementia. Each case costs $41,000 to $56,000 a year, the study found. By comparison, direct expenses in the same year for heart disease were $102 billion. The study also tried to get a handle on the cost of informal care, which is often provided by family members in their homes. It pegged that cost at a range of $50 billion to $106 billion a year.

In a press release dated 24 January 2014, the Alzheimer’s Society and Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF) are reported in their “Drug Discovery Programme” as offering up to $1.5 million to new research projects which could speed up developing treatments for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and dementia. It is hoped that international collaboration could help make the hope of finding effective dementia treatments within the next ten years a reality. This call is open for research looking at all forms of dementia including Alzheimer’s disease. This international call for research proposals comes just weeks after the G8 Dementia Summit in London called for more global collaboration in dementia research in order to develop effective treatments by 2025.

It is described in this promotional video as “halting dementia in its tracks”. To “halt something in its tracks” literally means “stop (dead) in something tracks to suddenly it stop moving or doing something”.

A previous research grant from the Alzheimer’s Society looked at fruit flies. It was for Dr Onyinkan Sofola at University College London for £208,277. It started on October 2007 and was completed on September 2010. The researchers developed a fruit-fly model of Alzheimer’s disease where the flies accumulated amyloid, and investigated the involvement of “GSK-3″ on the behaviour of the flies. It was hoped that dialing down GSK-3 in healthy flies also did no harm suggesting this approach could work as a safe therapy for Alzheimer’s disease in humans.

Ahead of the G8 Dementia Summit in London last year (11 December 2013), Professor Simon Lovestone, Institute of Psychiatry, but soon to be at Oxford, set out what he hopes the Summit will achieve, the challenges of developing new therapies for dementia, and the real possibilities of one day preventing this devastating disease. The Summit was supposed to bring together Health Ministers from across the G8, the private sector and key international institutions to advance thinking on dementia research and identify opportunities for more international collaboration, with the ultimate aim of improving life and care for people with dementia and their families.

The G8dementia summit was described as a response thus by the BBC website:

Drugs currently used to treat Alzheimer’s Disease have limited therapeutic value and do not affect the main neuropathological hallmarks of the disease, i.e., senile plaques and neurofibrillar tangles. Senile plaques are mainly formed of beta-amyloid (Abeta), a 42-aminoacid peptide. Neurofibrillar tangles are composed of paired helical filaments of hyperphosphorylated tau protein.

New, potentially disease-modifying, therapeutic approaches are targeting Abeta and tau protein. Drugs directed against Abeta include active and passive immunisation, that have been found to accelerate Abeta clearance from the brain. The most developmentally advanced monoclonal antibody directly targeting Abeta is bapineuzumab, now being studied in a large Phase III clinical trial.

In the 1980s, the amyloid cascade hypothesis emerged, and it was the most long considered theory. It is based on the ?-amyloid overproduction as responsible for the senile plaque formation and for the neurotoxicity that leads to the progressive neuronal death. However, controversial data about if ?-amyloid is the cause of the disease or one of the main risk factors for AD are reported.

A further postulated theory at the end of the past century was the tau-based hypothesis. It is based on aberrant tau protein, a microtubule-associated protein that stabilizes the neuronal cytoskeleton, as the origin of Alzheimer’s pathology. There have been two phase IIb clinical trials with two different compounds, tideglusib and methylene blue. Both compounds have reported some positive results in the increase of cognitive level of AD patients after the first treatments on phase IIa clinical trials.

In the meanwhile, intensive research on the physiology and pathology of tau protein leads to the discovery of two kinases responsible for its posttranslational aberrant modifications. After cloning, these kinases were identified more than ten years ago, including the now well-known glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3).

The excitement of this “GSK3 hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease” is described here in this paper with Professor Simon Lovestone as last author.

But all may not be as well as it first appears.

GSK-3 inhibition may be associated with significant mechanism-based toxicities, potentially ranging from hypoglycemia to promoting tumour growth. But encouragingly, at therapeutic doses, lithium is estimated to inhibit approximately a 25% of total GSK-3 activity, and this inhibition degree has not been associated with hypoglycemia, increased levels of tumorigenesis, or deaths from cancer. Currently it’s hoped, in pathological conditions, the GSK-3 inhibitor would be able to decrease the upregulation of the enzyme and, in the case that this treatment would slow down the GSK-3 physiological levels, other compensatory mechanisms of action would play the restorative function.

Therapeutic approaches directed against tau protein include inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase- 3 (GSK-3), the enzyme responsible for tau phosphorylation and tau protein aggregation inhibitors. NP-12, a promising GSK-3 inhibitor, is being tested in a Phase II study, and methylthioninium chloride, a tau protein aggregation inhibitor, has given initial encouraging results in a 50-week study. Fingers crossed.

Another important challenge for a GSK-3 inhibitor as an AD treatment is its specific brain distribution. The drug needs to cross the blood-brain barrier to exert its action in the regulation of exacerbated GSK-3 brain levels. Usually this is not an easy task for any kind of drug, moreover when oral bioavailability is the preferred administration route for chronic dementia treatment.

And once it gets into the brain, it has to to go to the right parts where GSK-3 needs to be targeted, not absolutely everywhere, it can be argued.

Nonetheless, the enthusiasm about the approach of drug treatments is described on Prof Simon Lovestone’s page for the Alzheimer’s Society.

However, Professor Lovestone’s research group has run into problems when trying to demonstrate their findings in mice, an important step in the research process. The problem is that mice do not naturally develop Alzheimer’s disease, and it is even difficult to experimentally cause Alzheimer’s disease in mice.

We may soon have to face up to the concept, with the current NHS having to do ‘more with less’, and ‘with no money left’, ‘we can’t go on like this’. It would be incredibly wonderful if you could give an individual a medication which could literally ‘stop dementia in its tracks’. But even note the scientific research above is for Alzheimer’s disease, one of the hundred causes of dementia, albeit the most common one. Or we may have to stop this relentless spend on finding the “magic bullet” in its tracks, and think about practical ways of enhancing the quality of life or wellbeing of those currently living with dementia. Nobody reasonable wishes to snuff out hope for prevention or cure of the dementias, but, for a moral debate, the facts have to be on the table and clear. Every money we spend on investigating magic bullets which don’t work could have been spent in giving a person living with dementia adequate signage for his environment, or a ‘memory phone’ with photographs of common contacts. But the drug industry, and the people who work with them, never wish to admit they’re running out of steam.

Are we actually promoting the NHS ‘choice and control’ with the current caredata arrangements?

In the latest ‘Political Party’ podcast by Matt Forde, an audience member suggests to Stella Creasy MP that wearing a burkha is oppressive and should not be condoned in progressive politics. Stella argued the case that she can see little more progressive than allowing a person to wear what he or she wants.

The motives for why people might wish to ‘opt out’ are varied, but dominant amongst them is a general rejection of commercial companies profiteering about medical data without strict consent. This is not a flippant argument, and even Prof Brian Jarman has indicated to me that he prefers a ‘opt in’ system:

Patients are not fully informed about how their information will be used. For such confidential data they should have to opt in @legalaware

— BrianJarman (@Jarmann) January 28, 2014

If people are properly told the pros and cons they can decide if they want to accept the cons, for the sake of the pros @sib313 @legalaware

— BrianJarman (@Jarmann) January 27, 2014

There are potential benefits, but also risks and if the risks happen they’re irreversible. Hence it’s safer to have opt-in. @legalaware

— BrianJarman (@Jarmann) January 27, 2014

Opting out can be argued as not being overtly political, though – it is protecting your medical confidentiality. People may (also) have political reasons for doing this, but the choice is fundamentally one about your right to a private family life. The government (SoS) has accepted this, and that is why it is your NHS Constitution-al right to opt out – you don’t have to justify it and if you instruct your GP to do it for you, she must.

It’s argued fairly reliably that section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 maps exactly onto Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001. Section 60 was implemented the following year under Statutory Instrument 2002/1438 The Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002. It is argued that the Health and Social Care Act 2012 did not modify or repeal those provisions of the HSC Act 2001 or the NHS Act 2006, nor did it modify or repeal any related provision of the Data Protection Act 1998. SI 2002/1438 remains in force. However, noteworthy incidents did occur under this prior legislation, see for example this:

Whatever motive you have for arguing against care.data, whether the whole principle of it, the HSCA removing any requirement for consent, the fact that it is identifiable data being uploaded from GP records (i.e. not anonymised or pseudonymised), or that the data will be made available, under section 251, for both research and non-research purposes, to organisations outside of the NHS, etc, the matter remains that the is no control over your data unless you opt-out.

Proponents of the ‘opt out’ therefore propose their two lines of action: either prevent your identifiable data being uploaded (9Nu0) and so effect a block on the release of linked anonymised or pseudonymised (potentially identifiable) data, which otherwise you cannot prevent or control; or block all section 251 releases (9Nu4), whether or not you apply the 9Nu0 code.

The point is, they argue, that you – the patient – cannot pick and choose, when, to whom, or for what purposes your data will be released. You cannot prohibit your data from being released for purposes other than research, or to organisations out with the NHS. This is completely at odds to the ‘choice and control’ agenda so massively advanced in the rest of the NHS. While it has been argued that the arguments against commercial exploitation of these data should have been made clearer beforehand, it’s possibly a case ‘I know we’re going there, but I wouldn’t start from here.’

Compelling arguments have been presented for the collection of population data. It’s argued wee need population data to do prevention and to monitor equity of access and use. It’s an open secret that the current Government is continuing along the track of privatising the NHS; arguably making it all the more important to have good data so we know what is happening. Having more of this data at all starting in the private sector, under this line of argument, is much less transparent, as it’s hidden from freedom of information from the start.

It’s, however, been argued that “the route to data access” has in fact changed. Under Health and Social Care Act (2012), it was intended that either the Secretary of State (SoS) or NHS England (NHSE) could direct HSCIC to make a new database, and – if directed by SoS or NHSE – HSCIC can require GPs (or other care service providers) to upload the data they hold. care.data represents the single largest grab of GP-held patient data in the history of the NHS; the creation of a centralised repository of patient data that has until now (except in specific circumstances, for specific purposes) been under the data controllership of the people with the most direct and continuous trusted relationship with patients. Their GP.

HSCIC is an Executive Non Departmental Public Body (ENDPB) set up under HSCA 2012 in April 2013. NHS England, the re-named NHS Commissioning Board, was established on 1 October 2012 as an executive non-departmental public body under HSCA 2012. Therefore, to suggest that the government has ‘little control’ over these arm’s-length bodies is being somewhat flimsy in argument – they were both established and mandated to implement government strategy and re-structure the NHS. There are also problems with the “greater good” argument; being paternalistic, the opposition to caredata spread bears similarity to the successful opposition to ID cards. This argument presumes that patients will benefit individually, when – and it ignores the fact that it is neither necessary or proportionate –and may be unlawful under HRA/ECHR – to take a person’s most sensitive and private information without (a) asking their permission first, and (b) telling them what it will be used for, and by who. Nobody is above the law, critically.

The fact is that the data gathered may increment the data available to research but that in its current form, care.data may actually not be that useful – it includes no historical data, for starters. And all this of course ignores the fact that care.data (and the CES that is derived from linking it to HES, etc.) will be used for things other than research, by people and companies other than researchers. That is the linchpin of the criticism. Finally, the Care Bill 2013-14 – just about to leave Committee in the Commons – will amend Section 251, moving responsibility for confidentiality from a Minister (tweets by Ben Goldacre here and here).

Anyway, the implementation of this has been completely chaotic, as I described briefly here on this Socialist Health Association blog. What now happens is anyone’s guess.

The author should like to thank Prof Ross Anderson, Chair of Security Engineering at the Computer Laboratory of the University of Cambridge, Phil Booth and Dr Neil Bhatia for help with this article.

Will the war over NHS privatisation be won on the social media or on Question Time?

In his lecture for the LSE recently called “These European Elections Matter”, Nigel Farage explained how the 1999 European Elections had been a ‘gamechanger’. This election had apparently returned three MEPs, and Farage explained that this result had only been achieved through the method of proportional representation. Farage concluded that, despite no MPs, this had meant UKIP was suddenly being involved in contemporary political debates on the BBC such as “Question Time” or “Any Questions”.

The situation how the UK entered Europe is almost a counterpoint to the situation why people want the NHS to leave behind market dynamics. The United Kingdom referendum of 1975 was a post-legislative referendum held on 5 June 1975 in the United Kingdom to gauge support for the country’s continued membership of the European Economic Community (EEC), often known as the Common Market at the time, which it had entered in 1973 under the Conservative government of Edward Heath. Labour’s manifesto for the October 1974 general election promised that the people would decide “through the ballot box” whether to remain in the EEC. The electorate expressed significant support for EEC membership, with 67% in favour on a 65% turnout. This was the first referendum that was held throughout the entire United Kingdom.

There has never been as such a referendum on whether the market should be forced to leave the NHS, but many feel that this is an equally totemic issue. It’s quite possible that the 2015 general election on May 7th, will have a low turnout generally if all the main political parties fail to capture the imagination of the general public. Using a market entry analogy, the question is how UKIP and NHAP enter the market of politics. It’s possible that UKIP could manage to come top in the European elections, though this is yet to be seen. UKIP are not opposed to UK in some sort of market with Europe, whilst wishing to not be embroiled in ‘spending £7 million a day for something undemocratic and unaccountable from Brussels’. Likewise, NHAP (National Health Action Party) is also concerned about the lack of democracy and accountability which appears to have become a pervasive theme in English NHS policy, and wish the NHS not to be fettered by the markets (for example European competition law). UKIP appear virtually weekly on Question Time, so the question is in part how can health issues compete for air time? Labour could even benefit from their greater presence in explaining their health policy, which is supposedly to escape the free market and TTIP. And NHAP could hold Labour to account on this issue, and other significant issues such as NHS reconfigurations and PFI. Conversely, UKIP is all for free trade.

Dr Lucy Reynolds soldiers on. As an academic in the highly prestigious London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Reynolds has developed an understanding of health policy which is unrivalled by many. Lucy has been quite successful in getting her well informed views across in the social media.

Dr Lucy Reynolds doesn’t have the luxury of Question Time.

Nigel Farage’s main complaint about Question Time is one of hostility to his party’s stance:

“I am one of the few people who can’t really complain about the editorial policy of Question Time having been on it 26 times since I was first elected in 1999. In terms of the coverage it gives Ukip I have found it fair and in the past few years the programme has even started accepting Ukip panellists other than me! But there have been a couple of programmes in which my colleagues and I have faced a hostile audience which in no way represents how Ukip is normally received or which are representative of the opinion polls. I am not pointing the finger of blame at the QT team but the question I want to ask is whether the Question Time audiences being exploited by the hard left?”

Even when Question Time was recently hosted at Lewisham, the number of questions on the NHS was kept to a bare minimum. This has been a general trend with this flagship TV programme, although the producers consistently cite that they can only air debates on questions proposed by audience members. However, occasionally dissent does ‘break though’ unpredictably. There have been over 86,000 ‘hits’ for a lady in the audience in Lewisham QT here

If it feels as if Nigel Farage is rarely off Question Time, that’s because he isn’t. Farage appeared more times on the programme than any other politician in the last four years. Top performers on #BBCQT include Nigel Farage, Vince Cable, Ken Clarke, Caroline Flint, Peter Hain, Caroline Lucas, Theresa May, and Shirley Williams. The arguments for Farage appealing to producers are that he is charismatic, inspires debate and helps them to fufil their requirement to give representation to smaller parties. But surely the same can be said for some experts in health policy?

Dr Louise Irvine (@drmarielouise), a GP in New Cross, south east London, and chair of the ‘Save Lewisham A&E’ campaign, has recently announced she will be standing for the National Health Action Party in the European Parliament elections on the 22 May 2014. Dr Irvine has said the NHS was under threat from an impending EU-US trade deal and the Government’s policies of ‘top down reorganisation, cuts and privatisation’.

She said: ‘I want to use this election to raise awareness of the imminent danger posed to the NHS by the EU/US trade agreement which will allow American companies to carve up the NHS and make the privatisation process irreversible.

‘I also want to alert the public to the gravity of the threat to the NHS from this Government with its programme of cuts, hospital closures and privatisation and to send a powerful message to politicians in Westminster and Brussels that people will not stand by and let their NHS be destroyed.

‘If elected, I will strive to ensure that EU regulations don’t adversely affect the NHS and are always in the best interests of the health of British people. The health of the nation spans all areas of policy from the environment to the economy.’

Dr Irvine is not only the “new kid on the block”. Rufus Hound is planning to run for the European Parliament to campaign against the privatisation of the NHS, saying he wants to preserve “one of the single greatest achievements of any civilisation”. In an impassioned blog post, he accused the Conservatives of wanting to sell off the health service to party donors – claiming that the Health Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, was “killing the NHS so that his owners can bleed you dry”.

The NHA was set up by Dr Richard Taylor, a former independent MP, to campaign against the Government’s Health and Social Care Act, introduced under the previous health secretary, Andrew Lansley. The party plans to field 50 candidates in the 2015 general election. Dr Clive Peedell (@cpeedell) has also been talking to the social media to get the NHAP’s message across’ he is one of the co-leaders.

The Max Keiser/Clive Peedell interview is here.

To give them credit, Dr Marie Louise Irvine and Rufus Hound offer us a chance to discuss the NHS, in the same way Nigel Farage and, say, Patrick O’Flynn (@oflynnexpress) offer us a chance to discuss our membership of Europe. The criticism is that they represent single issues and do not have a coherent corpus of policies across the full range of policy areas, and indeed have no realistic chance of forming a government. But paradoxically they both do offer a chance for domestic policy to operate in such a way Portcullis House doesn’t become another neoliberal outpost of the Federal United States of Europe. In the NHS’ case, socialism might only survive if it is not engulfed with yet more Atlantic Bridge-type stuff next parliament. But UKIP would not probably stop that. Who knows if Labour would be able to either in reality.

The NHS – the cash cow that keeps on giving

It’s perfectly possible to run a public service into the ground. Then say it’s shit. Then privatise it. Look at British Rail.

The NHS represents the ultimate golden goose. It is pictured as a drain of resources, while year after year it runs at super efficiency supposed to deliver cumulatively £20bn ‘efficiency savings’? And where does this money go? Answers on a postcard. It’s all a big scam, as the Government then consults on what could deliver better care: and after a few Cs, the answer is compassion. What a surprise.

If we had the same level of revolts as in Greece and Spain at this drive in the name of ‘austerity’, ‘sustainability’, or ‘doing more for less’, or any other trite saying which springs to mind, the number of people of arrested could in theory fill private prisons many times over. It doesn’t matter if some of these are ‘false arrests’, as an outsourcing company could run the appeals process for another arm of the outsourced criminal justice system. The State of course doesn’t have to pay for it having torpedoed legal aid. Look at what the criminal barristers are up to.

Guilty when you’re innocent is the legal equivalent of the ‘false positive’. It’s perfectly possible to rustle up false positives in many areas of medicine. Take for example finding the odd demyelinating plaque on a neuroimaging scan, which could then be further investigated by a lumbar puncture, to rule out multiple sclerosis. Or take for example a twang of musculoskeletal pain which gets combined with a borderline blood test result so that an individual ends up having a catheter inserted up his groin to have a look at the arteries in the heart.

The possibilities are endless. This is what goes wrong when you open up the wrong markets. There are many who disagree with the market ethos, and expect Labour to go through the motions of opposing the market. The question though can be asked what exactly it has been done to oppose the TTIP (EU-US Free Trade Treaty), when MPs have been extolling its virtues in other sectors. And does the Labour Party wish to chuck out those MPs or Lords who clearly have been alleged to have conflicts of interest affecting how they vote on matters of competition or procurement law?

Public anger at a cash-starved NHS might get Labour into government, but what happens when Labour comes into government? Certain things, such as the TTIP or European procurement directives) might suddenly come beyond the control of Labour. The ‘efficiency savings’ are set to continue. Will they do anything about the ‘efficiency savings’? Ed Balls yesterday boasted of ‘the Fabian way’, but the description he gave was very free-market with the NHS or socialism barely mentioned. It’s a moot point whether this is of course the ‘Fabian Way’, but the logo of the Fabians used to be a ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing’.

What would a unified budget mean for a combined NHS and social care service? Quite simply, it could become the second reincarnation of ‘The Big Society’. This concept was widely criticised as being a cover for cuts, but a means of legitimately ‘shrinking the state’. The two concepts have thus far not been explained well, although it’s still early days for ‘whole person care’. Merging the budgets could make it much easier to hide further under-resourcing of services. It is potentially a neoliberal shoo-horn, but in the maelstrom of the Labour Party acting as the caped crusader, nobody might notice.

And of course if work pays, private business pays even better. There’s still money to be made from people trapped in the system, if they are incorrectly charged with an offence or wrong diagnosed with a medical condition. If the Government wishes concomitantly to up the number of diagnoses in conditions, you could see the perfect storm, as in the national dementia policy. Things are normally charged on the basis of what it costs plus a bit of a profit, and of course the directors of private companies are obliged to return a porky shareholder dividend.

Yep, it’s the cash cow which keeps on giving. Who knows what Simon Stevens, ex head of a multinational, will make of it as head of the NHS this year.

Is it “ageist” to suggest ‘downsizing’ to promote wellbeing in older people with dementia living independently?

You can currently view the dementia debate in the House of Lords from 22 January 2014 here:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/democracylive/house-of-lords-25848095

The whole of this debate was extremely interesting, but one particularly societal housing issue was raised amidst the discussions.

One argument is that many of us are living in accommodation unsuitable for our needs anyway.

Lord Best, a Cross-Bench peer, introduced the notion of ‘downsizing’ in housing for older residents including people living with dementia, to improve their wellbeing:

“The Hanover@50 website displays the input from nine national think tanks on questions of housing and care for older people. In summarising these contributions to the debate that Hanover organised to mark its 50th anniversary, I contributed a 10th chapter, called, “Accommodating our extended middle age”. This addresses two of the most significant problems facing the UK: first, the escalating health and social care requirements for those in later life and, secondly, the acute shortages of homes for younger households. The proposed solution to both problems is to build attractive, well designed homes for those in their extended middle age—55 to 75 years-old—and create a sea change in attitudes in the UK to downsizing or “right sizing”.

If even a modest proportion of the rapidly growing number of older, single people and couples living in family homes could be enticed—by spacious, light, energy-efficient new homes—to downsize, there would be huge gains for them and for the nation: improved health and well-being for movers; liberation from looking after bigger homes and gardens; reduced accidents in the home or illnesses linked to cold or damp; and pre-empting, postponing and preventing loss of independence and enforced moves into expensive residential care in later life.

Downsizing retirees can access wealth by releasing equity, and this can pay for care, assist the next generation or simply fund happier retirement. Standards of living can be dramatically improved, and the setting of “sociable housing” for those in extended middle age can reduce the likelihood of loneliness and isolation, which are the chief causes of misery and mental health problems for older people.”

Most discussion about kick-starting housing focuses on first-time buyers. But local authorities, arguably, could do much more to help older people live in homes that are suitable for their needs later in life

As an ageing society – where buying a first home has been a rite of passage for decades – we tend not to discuss openly or explicitly about what kind of housing people need as they get older.

This should encourage an approach of solidarity, collaboration, cooperation and reciprocity. It’s also, potentially, a question about fundamentally pooling resources.

Housing quality and choice are key to a successful ageing society: good housing allows easier care delivery and often represents significant housing wealth that can help to maintain or improve lifestyles as we age.

They have invited nine prominent think tanks from across the political spectrum to contribute to the Hanover@50 Debate. Their provocative views aim to prompt a fresh look at housing and ageing.

Interestingly, the sixth think piece in the Debate, ‘Downsizing in later life and appropriate housing size across our lifetime’, calls for a fresh look at under-occupation and housing in later life.

Author of the piece, Dr Dylan Kneale, argues that asking older people alone to downsize is “ageist”: his argument is that we should be discouraging under-occupation through life. Dr Kneale suggests that it is in the interest of us all to consider how much housing we consume and the benefits of this in financial and other terms. In English equality law, an offence is produced if a prohibited behaviour is conducted against a protected characteristic to a group of people (in indirect discrimination). So is “targeting” older people with dementia to live well “ageist”?

The University of Stirling have produced an excellent publication entitled. “Improving the design of housing to assist people with dementia”.

But there has been relatively little work looking at the overall size of the accommodation of persons living independently with dementia.

It is, arguably, in the interests of society generally that expenditure on health services and residential care is reduced wherever possible. Good dementia design can enable people to remain at home for longer and can also reduce the likelihood of them having falls.

One of the main reasons why people go into a care home is because they have had a fall. Other positive outcomes of good design can include lower levels of agitation, confusion, restlessness and disorientation because the person is less distressed. So, is it actually “ageist” to identify a group particularly at risk, older people with dementia, and to think about what might be more suitable for their aspirations to live independently?

This is particularly important, if you consider that the purpose of policy is to encourage older people with dementia to live better independently.

Sledgehammers and nuts: opt-outs and data sharing concerns for the NHS?

You couldn’t make it up.

“a substantial number of GPs are so uneasy about NHS England’s plans to share patient data that they intend to opt their own records out of the care.data scheme.”

“The survey of nearly 400 GP respondents conducted this week found the profession split over whether to support the care.data scheme, with 41% saying they intend to opt-out, 43% saying they would not opt-out and 16% undecided.”

Simon Enright, Director of Communications for NHS England, tweeted to indicate methodological issues with concluding too much from this ‘snapshot survey':

@legalaware disappointing that Pulse did self-selecting sample with potential question bias in survey.

— simonenright (@simonenright) January 26, 2014

And of course Simon Enright is right. But one has to wonder how much GPs themselves have been informed about the debate about data sharing concerns. GPs are trained to explore, and in fact examined on exploring, the ‘beliefs, concerns and expectations’ of their patients; so it would be unbelievable to assume that no one had had this particular conversation with a patient.

GPs tend to be a very knowledgeable and versatile group of medical professionals, and indeed many have an active interest in public health.

But here there’s been another problem at play? All of the patients who I know, because of the known issues in waiting for an appointment to see their GP for ‘routine matters’, have decided to opt-out by simply dropping in to sign a form with the receptionist. But that sample could even be more unreliable than the Pulse survey.

For all of the huge budget that’s set aside for NHS England’s interminable activities on patient engagement in the social media and beyond, you’d have thought a spend on explaining data sharing would’ve been money well spent?

Views on an individual’s right to ‘opt out’, described in a previous blogpost of mine, vary.

There are many good arguments for proposing the sharing of care data, but the lack of willingness of industry, primary care or public health to discuss openly how data sharing might be necessary and proportionate, under the legal doctrine of proportionality, is utterly bewildering.

What has resulted is an almighty mess.

In as much as there is a ‘root cause’ of this problem, an unwillingness to make the arguments for data sharing with the general public is a good candidate.

Julie Hotchkiss, a public health physician, has for example written to Tim Kelsey about the matter today.

Dear Mr Kelsey

re:Care.data

I think there is so much to be gained by collation of personal health data – for epidemiological observation (prevalence, time trends, variation), allowing data-linkage enjoyed by other countries such as Sweden, to aid commissioning of health services as well as, of course, for direct patient care. For all these reasons I support in principle the care.data initiative. However I have grave concerns about how the data might be used. I am aware that many, many people share these concerns, and many of these have been expressed in the press in recent weeks. Many of my colleagues (long term NHS employees) are saying they will opt out. There are a number of senior voices in the Public Health world who are urging people to opt out.

NHS England is in a unique place to be able to address these concerns – but in many ways the horse has bolted, and I fear we may never get it back in the stable. PLEASE now put your energies and resources into a full and frank consultation, including IT experts, medical colleges, academia and for goodness sake – the general public! The fact that no such awareness raising and consultation has taken place makes people suspicious. They already don’t blindly trust the NHS / government anymore. So if you want to get health professionals and academics behind you in order to have a greater number of voices advocating for care.data please address the following concerns – in a published document- as soon as possible.

- definitive ownership of the data

- responsibility for data quality

- assurance (ideally in legislation) that ownership or data management will remain with a governmental agency and not be out-sourced

- will the HSC IC own the data, and allow access through a form of brokerage (allowing specific views/queries) or access to the full data set)?

- detailed Information Governance arrangements, e.g. requirements for Section 251 approval?

- what Research Governance / Ethical approval arrangements are being put in place?

- what will organisations have to pay,? and if so is this a handling fee or will they get ownership of the data?

- criteria for granting access to data and legally binding restrictions on usage of the data

- exactly to what extent will records be identifiable (for instance the long-established practice at ONS of suppressing cells with fewer than 5 individuals from disclosure)

Although I expect a response, more than this I expect published documents to detail all these issues. I’m sure there are many other details specialists in health research, Information Governance, medico-legal matters and civil libertarians would require in order to be assured that this was something in which they could participate.

Kind regards

Julie Hotchkiss, Fellow of the Faculty of Public Health

Another question for Tim Kelsey may be, potentially, whether the data from care.data will be processed according to the National Statistics Code of Practice.

It is somewhat unclear why the public health community have not had themselves a discussion with the general public, despite some advocates of this community now complaining very loudly about the presentation of ideas leading to the ‘opt out campaign’.

But they will need to confront the stench of public mistrust aimed at various politicians. Examples of events leading to this profound distrust include the NSA/Snowden affair, and relevations at GCHQ.

The corporate capture in some areas of public health is not a topic which public health physicians have wished to talk about. However, these authors somehow managed to sneak an excellent discussion of the phenomenon here in the British Medical Journal.

There have been calls for much tighter regulation of “data brokers”, as corporates wish to rent-seek this plethora of data. What always appeared to have been lacking was an “intelligent debate” with the general public about data sharing. Nonetheless, the social media, for example “Open democracy: our NHS” websites, have for a very long time been publishing relevant articles on this subject.

There was also the small issue of how the £3bn implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) came into being, which led to a turbo-boost of the outsourcing and privatisation of the NHS. Members of the academic public health community were slow on the uptake there too – some would say “completely asleep on the job”, perhaps not as far as their own research interests are concerned, but on the specific issue of potential violation of valid consent for individuals.

And guess what the Health and Social Care Act (2012) also contains a legal ‘booby trap’, which many did not see fit merited discussion with the general public.

Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 (originally enacted under Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001), allows the common law duty of confidentiality to be set aside in specific circumstances where anonymised information is not sufficient and where patient consent is not practicable. For example a research study may require access to patient identifiable data to allow linkages between different datasets where the cohort is too large for consent.

This would require time limited access to identifiable information where gaining consent from a large retrospective cohort would not be feasible and would require more identifiable data than would be necessary for linkage purposes. However, section 10 of the Data Protection Act (1988) currently allows a right for an individual to prevent damage or distress by data processing.

This is indeed conveniently “triggered” by section 259(10) of the Health and Social Care Act (2010), i.e. “[the provision] is subject to any express restriction on disclosure imposed by or under another Act (other than any restriction which allows disclosure if authorised by or under an Act”:

The trust is further eroded through the loss of data from government agencies, coherently tabulated on this Wikipedia page.

Proponents of democratic socialism have long argued that citizens often are not able to buy influence through competing with large corporates, but can legitimately exert influence through the ballot box.

There is also no doubt that people are talking at cross-purposes. There is a bona fide case for disease registries and surveillance, for example. However, the problems of an individual’s data being shared with lack of informed valid consent in the name of population presumed consent do need to be addressed ethically at least.

Public health physicians who would like to see the law applied to promote public health and research overall cannot condone profiteering from personal data abuses. Tim Kelsey has always been adamant that the English law is strong enough to cope with such threats. The scenario has mooted before of private insurance companies being able to abort insurance contracts (rescission) from data disclosed to them, on the grounds of misrepresentation or non-disclosure, but the position of the NHS England has always been to present such scenarios as far-fetched.

However, the issues appear to have been intelligently debated at European level. The draft “EU General Data Protection Regulation on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data” (the EU Regulation), was published in 25 January 2012, and has been debated in the European Parliament for most of the time since then.

Under “Albrecht’s proposals“, health data should generally only be able to be processed for the purposes of historical, statistical or scientific research where individuals have consented to such processing. It would be legitimate for processing in the context of research to take place without consent only where: (a) the research would serve an “exceptionally high public interest”; (b) the research involves anonymous data from which individuals could not be re-identified; and (c) the regulators have given their prior approval. Consent, however, is to follow the stricter interpretation, requiring explicit, freely given, specific and informed consent obtained through a statement or “clear affirmative action”. There is, however, legitimate concerns that these proposals might damage the interests of both corporate and public health communities.

It looks very much like chaos has set in since 2010 in running the NHS. Any party can do better than this.

This is of course an almighty mess, and it is hard to know how the whole thing could have been approached better. A plethora of issues have converged seemingly at once, and there is a possibility a ‘big opt out’ would still deliver a result without the matters having been properly discussed. If you think this is bad, consider what would happen in a national discussion of the terms of our membership of the European Union?

by @legalaware

My presentation for my book launch of ‘Living well with dementia’ for 15/2/14

This is a talk I will be giving in Camden at 3pm to guests of mine, to celebrate the launch of my book on living well with dementia.