Home » Posts tagged 'personal budgets'

Tag Archives: personal budgets

A personal budget approach blind to the underlying neuroscience of dementia is doomed to failure

One of the critical messages in recent public health awareness campaigns about dementia is that there is much more to a person living with dementia than his or her actual diagnosis. This focus on personhood, how the person living with dementia understands himself or herself, in the context of his past, present and relationships, and in relation to his or her own environment, is of course critical. It is likely to be embraced in the overall approach of whole person care in this jurisdiction.

Much of the current policy in England in dementia is driven by a scant existence of relevant evidence, for example the mental distress and lack of appropriate management caused by false diagnoses of dementia not confirmed elsewhere in the system. For example, even in the eight years since the seminal paper by Gail Mountain in the journal ‘Dementia’ in 2006, we have had little progress in the literature on the extent to which people at various stages of different types of dementia are able to manage, or want to manage, their own conditions, depending on their cognitive, affective or motivational abilities. This blogpost is about the form of personal budgets where people with dementia are given the money directly to spend, without any broker.

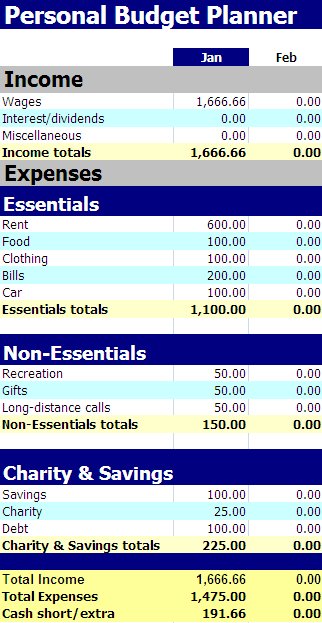

Likewise, the approach of personal budgets in dementia has equal scant regard to an approach necessitated by the cognitive neuroscience. Being able to operate a budget is likely to require a good understanding of mathematics; and it has been known for decades, or if not centuries, that people with disruption of the functioning of a part of the brain known as the parietal cortex can have problems with calculations. This is called ‘dyscalculia’.

Some people with dementia might have real problems in anticipating future outcomes (as shown in the famous Anderson paper) or have problems in making accurate cognitive estimates (as discussed in the famous paper by Shallice and Burgess). The people with dementia for whom these problems are likely to surface are those with disruption of the functioning of a part of the brain known as the frontal lobe.

Also, I showed myself in 1999, published in Brain, that people in early stages of behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia can be prone to make risky decisions. Others have argued it is more of a problem with impulsivity.

Nobody has any intention of turning people living with early stages of dementia into amateur accountants, but even with the basic budgets you need to have an ability to deal with income, expenditure, costing and reasonable forecasting.

So there is clearly an evidence base emerging that, despite full legal capacity, there are some persons living with dementia who are best not served by direct payments so that they can pursue their ‘choice’. But the introduction of this has been surreptitious, couched in language such as “empowering people with dementia to take control of their own risk behaviour.”

Such flowery language is best kept in marketing manuals, I feel. At a time when report after report has demonstrated that there is not a strong evidence base for improvement in clinical outcomes (such as falls for people with dementia), we must be able to ask for whose benefit are these self-directed budgets for people with dementia?

There is report after report of ‘widening the market’, complaining about the lack of quality ‘control’ of market offerings for dementia. And yet we simultaneously have a care regulator complaining regularly about the quality of dementia services in trusts in England. We have a poor evidence base on what level of budget is sufficient to allow a choice; clearly someone who has an insufficient budget cannot find a choice argument at all compelling.

And is the quality of market offerings being properly regulated to prevent fraud? The last few years has witnessed a series of seemingly attractive offerings for living well with dementia, some of which are extremely good (such as assistive technology, better design of wards and the home), and some of which are poor. There is insufficient evidence here too that the regulator is able to cope confidently except in the clearest examples of fraud.

There is much good work being done in social care and medicine, but with a drive for shiny, instant products, we must never lose sight of the fact that care from social care has been cut consistently over a long period of time. Whenever someone explains the case for personal budgets, there is almost certainly a concomitant explanation of an exploding care budget. However, it would be wrong to slash frontline care while touting ‘The Big Society’ in the same way it would be completely wrong to cut in real terms per caput allocations of care or to pursue backdoor rationing in the name of choice.

Personal budgets for dementia. What’s the harm in them, and are the right people benefiting?

Personal budgets held by individual people might allow more flexibility in choice and control over health services. So what’s the harm in them?

Barry Schwartz’s famous book “The paradox of choice”, summarising a lot of other evidence, contests the assumption that maximising collective welfare of citizens is achieved through maximising individual freedom.

On May 8th 2015, there’ll be a change in government in the UK (unless the arithmetic happens to throw up another Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, which is quite unlikely). It is likely that all the major political parties will wish to implement a form of ‘integrated’ or ‘whole person care’, with the merging of health and social care. It is a moot point how early on people, if at all, will be offered the chance of a ‘unified personal budget’.

A particular group of people for whom personal budgets may be considered are persons with dementia. It is therefore perhaps a bit disappointing that some of the same issues which existed many years ago are still lurking in some form even now. No matter how much effort you put into ‘compassion’ or ‘Dementia Friends’, the care system is never going to be acceptable in the light of dangerous financial cuts to social care. The “one size fits all” philosophy seems to be pervasive in the Government approach to personal health budgets, whichever Government pursues it. It’s as if it doesn’t matter who is the singer is because the song is the same: like Pharrell’s “Happy” was originally recorded by Cee Lo Green (allegedly).

Certain people with early dementia might be particularly prone to impulsive or risk-taking behaviour, so there is a reasonable question whether some persons with dementia – despite full legal capacity – are “safe” to have personal health budgets themselves. But this I feel strengthens my argument for a proper system of delivery of personal health budgets, not undermining them. When personal budgets work for dementia, as explained by Colin Royle here, they work very well.

A potential danger is that somebody is given a list of ‘options’ for care support planning, and effectively told to get on with it. It can be difficult to get to the precise details of resource allocation systems, and, without knowing such details, it is difficult to ascertain whether they legally constitute a process acting to the detriment of the group of people with dementia. This leaves individual local authorities open to an accusation of indirect discrimination, offending the Equality Act (2010). There are various sources of factors which might cumulatively cause certain people to be more disadvantaged than others: e.g. an ability to ‘self-assess’ one’s needs in a questionnaire (with age being a confounding factor).

Personal budgets might be offered in a number of ways: namely those which were directly commissioned and managed by the local authority, third party managed accounts, direct payments or a mixture of these things. Concerns might come from all sorts of quarters: such as actual budget holders who don’t feel that the resources allocated meet their needs, or the professions who don’t feel that certain candidates are suitable in the first place. This is perhaps one of those uncommon instances where ‘cutting out the middle man’ is in fact a dangerous idea. The actual calculation of resource allocation for an individual candidate is emphasised rather than the calculation of running the whole system adequately, in much the same way that the improvement in wellbeing in a personal budget might accrue from having a choice at all rather than the actual proposed care intervention.

Take, for example, this passage:

“Quality support planning needs the investment of time. In the ideal world, presented by those who ‘run with’ the agenda, everyone is able to take an active part in making decisions for themselves and choosing their own care to meet their needs, as defined by themselves. The reality is that some groups have not been able to engage in the process of taking an active role in their own support planning; they are effectively excluded. This may be because they lack the capacity to manage a direct payment or organise a personal budget themselves, or because they lack support systems around them, such as family to help them do this.”

Clearly not everyone has benefited from the “Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge”. For example, the Dementia Advocacy Network went bust at the end of last year. And yet this is precisely the time when people with dementia, and caregivers, need emotional support, and need to be safeguarded against forms of abuse including financial and legal. It appears that people who have benefited most from personalisation are those with the best advocacy and loudest voices. Even with the most-straightforward appearance of self-assessment application procedures for personal budgets might require an enormous amount of professional support. There are various reasons why persons with dementia might have special obstacles in their uptake of personal budgets, as articulated well by the Mental Health Foundation: two for example include a residual stigma and discrimination against such citizens, and also the fact that some citizens might not have a reliable correct diagnosis in the first place.

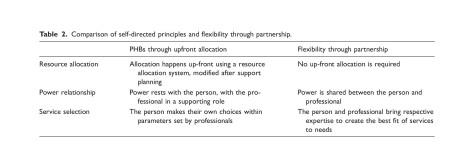

Self-directed support (SDS) has as its central feature a personal budget arrived at through an ‘up-front’ allocation of money; though up front allocation to give people power is one element of SDS amongst others and therefore it would be unfair to generalise across all the resource allocation systems techniques. It was introduced as formal policy in 2008, with an original target that all service users should have a personal budget for social care by 2011. In a recent helpful article, “Personalization of health care in England: have the wrong lessons been drawn from the personal health budget pilots?“, various well-known methodological problems with the original pilots are considered. The authors do, however, propose an extremely constructive way of moving forward, what they call “flexibility through partnership”.

Cheekily, the authors observe:

“As Gadsby points out ‘It seems that in many cases, additional resources[in the PHB group] were provided that enabled individuals to pay for extra services or one-off goods. It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that overall improvements were found in wellbeing amongst budget holders’”.

Without advocacy services, then, we really do run the danger of running a two tier service, and this is extremely dangerous, aside from the swathe of legal aid cuts. For a government which prides itself on parity, particularly for empowering new private providers to enter a liberalised market, any proposed system of personal budgets will require the same quality and opportunity for flexibility to all user groups including those who have no recourse to advocacy. A strengthened social care system would go a long way here. Nobody has a single right answer for personal budgets in dementia so it might not be able to have the exclusive kite mark to match. It’s clear whilst there might be excellent ways of implementing them, there are plenty of bad ways too.

Unfortunately, time is running out a bit, and political leadership and adequate funding – including for advocacy services – are now both essential. And who will benefit? If they work well, they will shift power to the people able to make ‘correct decisions’ in care, but I feel that the whole system has to be fit-for-purpose not the budget mechanism itself. That’s where the State comes in. Who the correct advocates are, as they might not necessarily be carers including unpaid caregivers (though they might be.) Ultimately, the most offensive irony would be to make the tool that offers choice and control compulsory, but this could be expected from politicians who like to give an illusion of choice.

There are still deeply engrained issues about whether people will have enough money to meet their needs. It might be easier to hide downsizing of budgets if they’re called a yet further new name. There are obviously huge problems with merging one universal system intended to be comprehensive and free at the point of need with one which is not and means-tested; and this would not necessarily benefit the person with dementia. And at worst, the wrong type of broker, not professional advocates including social workers, could be profiting but not providing overall benefit. Introducing any transactions into a system absorbs resources, however you attempt it.

We now have to be very careful with resolution of this potentially useful policy plank – otherwise it might be a case of ‘You’ll do’, rather than ‘I do’.

Personal budgets for dementia. What’s the harm in them, and are the right people benefiting?

Personal budgets held by individual people might allow more flexibility in choice and control over health services. So what’s the harm in them?

Barry Schwartz’s famous book “The paradox of choice”, summarising a lot of other evidence, contests the assumption that maximising collective welfare of citizens is achieved through maximising individual freedom.

On May 8th 2015, there’ll be a change in government in the UK (unless the arithmetic happens to throw up another Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, which is quite unlikely). It is likely that all the major political parties will wish to implement a form of ‘integrated’ or ‘whole person care’, with the merging of health and social care. It is a moot point how early on people, if at all, will be offered the chance of a ‘unified personal budget’.

A particular group of people for whom personal budgets may be considered are persons with dementia. It is therefore perhaps a bit disappointing that some of the same issues which existed many years ago are still lurking in some form even now.

No matter how much effort you put into ‘compassion’ or ‘Dementia Friends’, the care system is never going to be acceptable in the light of dangerous financial cuts to social care.

The “one size fits all” philosophy seems to be pervasive in the Government approach to personal health budgets, whichever Government pursues it. It’s as if it doesn’t matter who is the singer is because the song is the same: like Pharrell’s “Happy” was originally recorded by Cee Lo Green (allegedly).

Certain people with early dementia might be particularly prone to impulsive or risk-taking behaviour, so there is a reasonable question whether some persons with dementia – despite full legal capacity – are “safe” to have personal health budgets themselves. But this I feel strengthens my argument for a proper system of delivery of personal health budgets, not undermining them. When personal budgets work for dementia, as explained by Colin Royle here, they work very well.

A potential danger is that somebody is given a list of ‘options’ for care support planning, and effectively told to get on with it. It can be difficult to get to the precise details of resource allocation systems, and, without knowing such details, it is difficult to ascertain whether they legally constitute a process acting to the detriment of the group of people with dementia. This leaves individual local authorities open to an accusation of indirect discrimination, offending the Equality Act (2010). There are various sources of factors which might cumulatively cause certain people to be more disadvantaged than others: e.g. an ability to ‘self-assess’ one’s needs in a questionnaire (with age being a confounding factor).

Personal budgets might be offered in a number of ways: namely those which were directly commissioned and managed by the local authority, third party managed accounts, direct payments or a mixture of these things. Concerns might come from all sorts of quarters: such as actual budget holders who don’t feel that the resources allocated meet their needs, or the professions who don’t feel that certain candidates are suitable in the first place.

This is perhaps one of those uncommon instances where ‘cutting out the middle man’ is in fact a dangerous idea. The actual calculation of resource allocation for an individual candidate is emphasised rather than the calculation of running the whole system adequately, in much the same way that the improvement in wellbeing in a personal budget might accrue from having a choice at all rather than the actual proposed care intervention.

Take, for example, this passage:

“Quality support planning needs the investment of time. In the ideal world, presented by those who ‘run with’ the agenda, everyone is able to take an active part in making decisions for themselves and choosing their own care to meet their needs, as defined by themselves. The reality is that some groups have not been able to engage in the process of taking an active role in their own support planning; they are effectively excluded. This may be because they lack the capacity to manage a direct payment or organise a personal budget themselves, or because they lack support systems around them, such as family to help them do this.”

Clearly not everyone has benefited from the “Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge”. For example, the Dementia Advocacy Network went bust at the end of last year. And yet this is precisely the time when people with dementia, and caregivers, need emotional support, and need to be safeguarded against forms of abuse including financial and legal. It appears that people who have benefited most from personalisation are those with the best advocacy and loudest voices.

Even with the most-straightforward appearance of self-assessment application procedures for personal budgets might require an enormous amount of professional support. There are various reasons why persons with dementia might have special obstacles in their uptake of personal budgets, as articulated well by the Mental Health Foundation: two for example include a residual stigma and discrimination against such citizens, and also the fact that some citizens might not have a reliable correct diagnosis in the first place.

Self-directed support (SDS) has as its central feature a personal budget arrived at through an ‘up-front’ allocation of money; though up front allocation to give people power is one element of SDS amongst others and therefore it would be unfair to generalise across all the resource allocation systems techniques. It was introduced as formal policy in 2008, with an original target that all service users should have a personal budget for social care by 2011. In a recent helpful article, “Personalization of health care in England: have the wrong lessons been drawn from the personal health budget pilots?“, various well-known methodological problems with the original pilots are considered. The authors do, however, propose an extremely constructive way of moving forward, what they call “flexibility through partnership”.

Cheekily, the authors observe:

“As Gadsby points out ‘It seems that in many cases, additional resources[in the PHB group] were provided that enabled individuals to pay for extra services or one-off goods. It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that overall improvements were found in wellbeing amongst budget holders’”.

Without advocacy services, then, we really do run the danger of running a two tier service, and this is extremely dangerous, aside from the swathe of legal aid cuts. For a government which prides itself on parity, particularly for empowering new private providers to enter a liberalised market, any proposed system of personal budgets will require the same quality and opportunity for flexibility to all user groups including those who have no recourse to advocacy. A strengthened social care system would go a long way here.

Nobody has a single right answer for personal budgets in dementia so it might not be able to have the exclusive kite mark to match. It’s clear whilst there might be excellent ways of implementing them, there are plenty of bad ways too.

Unfortunately, time is running out a bit, and political leadership and adequate funding – including for advocacy services – are now both essential.

And who will benefit? If they work well, they will shift power to the people able to make ‘correct decisions’ in care, but I feel that the whole system has to be fit-for-purpose not the budget mechanism itself. That’s where the State comes in. Who the correct advocates are, as they might not necessarily be carers including unpaid caregivers (though they might be.) Ultimately, the most offensive irony would be to make the tool that offers choice and control compulsory, but this could be expected from politicians who like to give an illusion of choice.

There are still deeply engrained issues about whether people will have enough money to meet their needs. It might be easier to hide downsizing of budgets if they’re called a yet further new name. There are obviously huge problems with merging one universal system intended to be comprehensive and free at the point of need with one which is not and means-tested; and this would not necessarily benefit the person with dementia. And at worst, the wrong type of broker, not professional advocates including social workers, could be profiting but not providing overall benefit. Introducing any transactions into a system absorbs resources, however you attempt it.

We now have to be very careful with resolution of this potentially useful policy plank – otherwise it might be a case of ‘You’ll do’, rather than ‘I do’.

Can the English NHS enter a ‘period of calm’ if it wishes to introduce integrated care?

Sir David Nicholson, KCB, CBE, is Chief Executive of NHS England.

In 2010 Nicholson jokingly described NHS reform plans, the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012), as the biggest change management programme in the world – the only one “so large that you can actually see it from space.”

Andy Burnham MP gave a speech to The King’s Fund on 24 January 2013, entitled “‘Whole-Person Care’ A One Nation approach to health and care for the 21st Century”.

And the Conservative Party, with Jeremy Hunt MP as Secretary of State for Health, have been eyeing up ‘integration‘ too.

So, like many areas of policy such as the private finance initiative, personal budgets or ‘efficiency savings’, there might be considerable consensus amongst the main political parties about implementing a further transformational change in the English NHS.

In that famous King’s Fund speech, Burnham comments, “Second, our fragile NHS has no capacity for further top-down reorganisation, having been ground down by the current round. I know that any changes must be delivered through the organisations and structures we inherit in 2015. ”

This is coupled with, “While we retain the organisations, we will repeal the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and the rules of the market.”

The Health and Social Care Act (2012) as a legislative instrument, whatever the political bluster, had three main legislative aims.

It aimed to implement competitive tendering in procurement as the default option, thus expediting transfer of resources from the public sector to the private sector; it beefed up the powers of the economic regulator (“Monitor”) for this “market”; and it produced a preliminary mechanism for the managed decline of financially unviable entities in the NHS.

Therefore repealing the Act can be argued as a necessary and proportionate move for taking out the ‘competition jet engines’ of the NHS “market”.

Experience from a number of jurisdictions provides that the legal challenges in allowing integration (and bundling) within the framework of competition law are formidable.

There is a clinical case for integrated care, in allowing more co-ordinated care of the person across various disciplines, for example medical, psychiatric or social, for both health and disease.

If community services are ‘wired up’ with hospital services, provided that community services are not starved of money at the same time as hospital services, there is a good rationale in that the health of certain people, followed closely in the community, might not freefall so badly that they require admission to a medical admissions unit.

There is also a financial argument that integrated or whole person care might work, but clearly no political party will wish to prioritise this ahead of quality of clinical care, particularly given the current tinderbox of cuts in medical and social care.

But whichever way you look at it, ‘whole person’ care involves a huge cultural change; this has repercussions for how all professions conduct themselves in their care, especially with regards to community care, and has consequences for training of staff in NHS England.

And it is impossible to think that, whichever political party ultimately becomes responsible for introducing a whole person or integrated care approach, it won’t cost money.

For example, setting up the infrastructure for data sharing, whether clinical or for the purposes of unified budgets, has a long history of being expensive.

Estimates of the cost of the reorganisation just gone are a bit confused, but they tend to range between £2.5 and £3 bn.

The risk of turbulence can be, to some extent, mitigated against by known people at the helm, such as Andy Burnham or Liz Kendall, but the last thing the general public will wish is another period of massive upheaval.

It can be argued that these changes are ‘a good idea’, and it’s only a question of explaining the benefits to the general public, but, following the Health and Social Care Act and caredata, the track record of this current Government is nothing to write home about.

Twitter: @legalaware

Personal budgets and dementia

Currently in England, according to the Government, more than 15 million people have a long term condition – a health problem that can’t be cured but can be controlled by medication or other therapies. This figure is set to increase over the next 10 years, particularly those people with 3 or more conditions at once. Examples of long term conditions include high blood pressure, depression, and arthritis. Of course, a big one is dementia, an “umbrella term” which covers hundreds of different conditions. There are 800,000 people in the United Kingdom who are thought to have one of the dementias. However, a thrust of national policy has been directed at trying to remedy the diagnosis rate which had been perceived as poor (from around 40%).

The Mental Health Foundation back in 2009 had publicly set out a wish that there would be a high level of satisfaction among people living with dementia and their carers with planning and arranging the ongoing support they receive via the different forms of self-directed support, and that specific examples and stories of real experiences, both positive and negative, in the use of the different forms of self-directed support will have been shared. Indeed, various stories have been fed into the media at various points in the intervening years.

People, however, tend to underestimate the extent to which GPs cannot treat underlying conditions.

For example, a GP faced with a headache, the most common neurological presentation in primary care, might decide to treat it symptomatically, except where otherwise indicated.

A GP faced with an individual which is asthmatic may not have a clear idea about the causes of shortness of breath and wheeziness, but might reach for his or her prescription pad to open up the airways with a ‘bronchodilator’ such as salbutamol.

However, this option not only does not work effectively for memory problems in early Alzheimer’s disease for many (although the cholinesterase inhibitors might have some success in early diffuse Lewy Body’s Disease). It is also very relatively expensive for the NHS compared to other more efficacious interventions, arguably. In September 2013, it was reported that treatment of mild cognitive impairment with members of a particular class of medications, called “acetylcholinesterase inhibitors” was ‘not associated with any benefit’ and instead carried with them an increased risk of side effects, according to a new analysis. The “meta-analysis” – published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal – looked at eight studies using donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine in mild cognitive impairment.

These experts argued that the findings raised questions over the Government’s drive for earlier diagnosis of dementia, but the issue is that medications may not be the only fruit for a person with dementia in the future. One aspect of ‘liberalising the NHS’, a major Coalition drive embodied in the Health and Social Care Act (2012), is that clinical commissioning groups can ‘shop around’ for whatever contracts they wish, with the default option being competitive tendering through the Regulations published for section 75. When a person receives a timely diagnosis for dementia, it’s possible that a “personal health budget” might be open to that person with dementia in future.

A personal budget describes the amount of money that a council decides to spend in order to meet the needs of an individual eligible for publicly funded social care. It can be taken by the eligible person as a managed option by the council or third party, as a direct (cash) payment or as a combination of these options. At their simplest level, personal budgets involve a discussion with the service user/carer about how much money has been allocated to meet their assessed care needs, how they would like to spend this allocation and recording these views in the care plan.

For some, the debate about ‘personal health budgets’ is not simply an operational matter. They are symbolic of two competing political philosophies and ideologies. A socialist system involves solidarity, cooperation and equality (not as such “equality of provider power” such as the somewhat neoliberal NHS vs ‘any qualified provider’ debate). A neoliberal one, encouraging individualised budgets, views the market in the same way that Hayek and economists from the Austrian school view the economy: as one giant information system where prices are THE metric of how much something is worth. In contrast, the “national tariff” is the health version of interest rates, artificially set by the State. Strikingly, cross-party support is lent in the implementation of this policy plank, largely without a large and frank discussion with members of the general public at election time.

A major barrier to having a coherent conversation about this is that the major protagonists promoting personal budgets tend to have a vested interest in some sort for promoting them. That is of course not to argue that they should be muzzled from contributing to the debate. But it’s quite hard to deny that personal health budgets not offer potentially more choice and control for a person with dementia (possibly with a carer as proxy), unless of course there’s “no money left” as Liam Byrne MP might put it.

With the introduction of ‘whole person care’ as Labour know it, or ‘integrated care’ as the Conservatives put it, it is likely that policy will move towards a voluntary roll-out of a system where health and social care budgets come under one unified budget. No political party wishes to be seen to compromise the founding principle of the NHS as ‘comprehensive, universal and free-at-the-point-of-need’ (it is not as such ‘free’, in that health is currently funded out of taxation), but increasingly more defined groups are being offered personal budgets. Personal health budgets could lead to a change of emphasis from expensive drugs which in the most part have little effect, say to relatively inexpensive purchases which could have massive effect to somebody’s wellbeing or quality of life. Critics argue that, by introducing a component of ‘top up payments’, and with the blurring of boundaries between health and social care with very different existant ways of doing things, that ‘whole person care’ or ‘integrated care’ could be a vehicle for delivering real-time cuts in what should be available anyway.

On Wednesday 9 October 2013, Earl Howe, Lord Hunt and Lord Warner didn’t appear to have any issue about a duty to promote wellbeing in the Care Bill, though they differ somewhat on who should promote that particular duty. This is recorded faithfully in Hansard.

Wellbeing is certainly not a policy plank which looks like disappearing in the near future. Norman Lamb, Minister for State for Care Services, explicitly referred to the promotion of wellbeing in dementia in the ‘adjournment debate’ yesterday evening:

“There is also an amendment to the Care Bill which will require that commissioning takes into account an individual’s well-being. Councils cannot commission on the basis of 15 minutes of care when important care work needs to be undertaken. They will not meet their obligation under the Care Bill if they are doing it in that.”

The broad scope of the G8 summit was emphasised by Lamb:

“The declaration and communiqué announced at the summit set out a clear commitment to working more closely together on a range of measures to improve early diagnosis, living well with dementia, and research.”

And strikingly wellbeing has not been excluded from the dementia strategy strategy at all.

This is in contradiction to what might have appeared from the peri-Summit public discussions which were led by researchers with particularly areas in neuroscience, much of which is funded by industry.

Norman Lamb commented that:

“Since 2009-10, Government-funded dementia research in England has almost doubled, from £28.2 million to £52.2 million in 2012-13. Over the same period, funding by the charitable sector has increased, from £4.2 million to £6.8 million in the case of Alzheimer’s Research UK and from £2 million to £5.3 million in the case of the Alzheimer’s Society. In July 2012, a call for research proposals received a large number of applications, the quality of which exceeded expectations. Six projects, worth a combined £20 million, will look at areas including: living well with dementia; dementia-associated visual impairment; understanding community aspects of dementia; and promoting independence and managing agitation in people with dementia.”

In quite a direct way, the issue of ‘choice and control’ offered by personal health budgets needs to be offered from parallel ‘transparency and disclosure’, in the form of valid consent, from health professionals with persons with dementia in discussing medications. With so many in power and/or influence clearly trumping up the benefits of cholinesterase inhibitors, with complex and costly Pharma-funded project looking at whether any of these drugs have a significant effect on parts of the brain and so forth, both persons and patients with dementia need to have a clear and accurate account of the risks and benefits of drugs from medical professionals who are regulated to give such an account. This is only fair if psychological (and non-pharmacological) treatments are to be subject to such scrutiny particularly by the popular press.

The personal health budgets have particular needs, and they are obvious to those with medical knowledge of these conditions. Quite often there might be a psychological reaction of denial about the condition and needs, associated the stigma and personal fear about ‘having’ dementia; but this can be coupled with a lack of insight into the manifestations of dementia, such as the insidious behavioural and personality changes which can occur early on in the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. There might also fluctuating levels of need on a day to day basis; like all of us, people with dementia have ‘good days and bad days’, but some subtypes of dementia may have particularly fluctuating time courses (such as diffuse Lewy Body Dementia). Apart from the very small number of cases of reversible or potentially treatable presentations which appear like dementia, dementia is a degenerative condition and so abilities and needs change over time. This can of course be hard to predict for anyone; the person, patient, friend, family member, carer or professional.

So having laid out the general direction of travel of ‘personal budgets’, it’s clearly important to consider the particular challenges which lie ahead. In the Alzheimer’s Society document, “Getting personal? Making personal budgets work for people with dementia” from November 2011, a survey for “Support. Stay. Save.” (2011) is described. This survey was conducted in late 2010, and comprised people with dementia and carers across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In total there were 1,432 respondents. The survey asked whether the person with dementia is using a direct payment or personal budget to buy social care services. 204 respondents said that they were using a personal budget or direct payment to purchase services and care. In total 878 respondents had been assessed and were receiving social services support, meaning that 23% of eligible respondents were using a personal budget or direct payment arrangement. Younger people with dementia and their carers appeared more likely to have been offered, and be using, direct payments or personal budgets than older people with dementia.

This is intriguing itself because the neurology of early onset dementia. Two particular diagnostic criteria are diffuse Lewy Body dementia which tends to have a ‘fluctuating’ time course in cognition to begin with, and the frontotemporal dementias where memory for events or facts (“episodic memory”) can be relatively unimpaired until the later stages. Clearly, the needs of such individuals with dementia will be different from those who have the early onset of Alzheimer’s disease, where episodic memory is more of an issue. Such differences will clearly have an effect on the types of needs of such individuals, but it can be argued that the patient himself or herself (or a proxy) will be in a better position to know what those needs might be. A person with overt problems in spatial memory, memory for where you are, might wish to have a focus on better signage in his or her own environment for example, which might be a useful non-pharmacological intervention. Such a person might prefer a telephone with pictures of closest friends and family to remind him or her of which pre-programmed functional buttons. Such a small disruptive change could potentially make a huge difference to someone’s quality of life.

As the dementias progress, nonetheless, it could be that persons with dementia benefit from assisted technologies to allow them to live independently at home wherever possible. This is of course a rather liberal approach. It is a stated aim of the current Coalition government that they want to help people to manage their own health condition as much as possible. Telehealth and telecare services are a useful way of doing this, it is argued. According to the Government, at least 3 million people with long term conditions could benefit from using telehealth and telecare. Along with the telehealth and telecare industry, they are using the 3millionlives campaign to encourage greater use of remote monitoring information and communication technology in health and social care. It is vehemently denied by the Labour Party that ‘whole person care’ would be amalgamated with ‘universal credit’, forging together the benefits and budget narratives. Apart from anything else, the implementation of universal credit under Iain Duncan-Smith has been reported as a total disaster. But there is a precedent from the Australian jurisdiction of the bringing together of the two narratives, as described by Liam Byrne and Jenny Macklin in the Guardian in September 2013. In this jurisdiction, adapting to disability can mean that your benefit award is in fact LOWER. If the two systems merged here – and this is incredibly unlikely at the moment – a person with disability and dementia in a worst case scenario could find that what they gain in the personal budget hand is being robbed to pay for the benefits hand. Interestingly, in the Australian jurisdiction, personal health budgets have an equivalent called “consumer directed care”, which is perhaps a more accurate to view the emerging situation?

There are of course issues about the changing capacity of a person with dementia as the condition progresses, and this has implications for the medical ethics issues of autonomy, consent, ‘best interests’, beneficience and non-maleficence inter alia. Working through carers can be seen a good enough proxy for working directly with the person with dementia, and of course a major policy issue is a clear need to avoid financial abuse, fraud and discrimination which can be unlawful and/or criminal under English law. However this in itself is not so simple. A person with dementia living with dementia, and his or her carer(s) should not necessarily be regarded as a ‘family unit’. Furthermore, caring professional services – both general and specialist, and health and social care – may not be signed up culturally to full integration, involving sharing of information. For example, we are only just beginning to see a situation where some care homes are at first presentation investigating the medical needs of some persons with dementia in viewing their social care (and not all physicians are fluent in asking about social care issues.) It is possible that #NHSChangeDay could bring about a change in culture, where at least NHS professionals bother asking a person with dementia about his perception and self-awareness of quality of life. This is indeed my own personal pledge for staff in the NHS for #NHSChangeDay for 2014.

I, like other stakeholders such as persons with dementia, can appreciate that the ground is shifting. I can also sense a change in direction in weather from a world where people have put all their eggs in the Pharma and biological neuroscientific basket. Of course improved symptomatic therapies, and possibly a cure, one day would be a great asset to the personal armour in the ‘war against dementia’. Of course, if this battle is won, the war to ensure that the NHS is able to provide this universally and free-at-the-point-of-need is THE war to be won, whatever the direction of ‘personal health budgets’. But I feel that the direction of personal health budgets has somewhat a degree of inevitability about it, in this jurisdiction anyway.

Thanks to @KateSwaffer for help this morning too.