Home » Posts tagged 'outsourcing'

Tag Archives: outsourcing

Politicians need to wipe the blood from their hands from liberalising the NHS

All the main political parties in England have “blood on their hands”, and we’re never going to get anywhere near the Chilcot Inquiry to sort out how it happened. The ‘weapons of mass destruction’ unleashed by corporate agents seeded everywhere in think tanks, media and politics have gone out of the way on a tirade of abuse against workers in the public sector. There are so many nexuses which have become uncoupled, that the NHS and social care systems no longer have anything like a situation approaching credibility.

Top CEOs in the NHS in England can still receive generous renumeration, even if their patient records are worse than the Black Hole of Calcutta. Even if multinational corporates do not perform adequately on a contract, the NHS does not have the legal know-how to ‘performance manage’ these contracts, and will not wish to spend the money. The NHS is scared of imposing any penalties, because of the powerful lawyers of multinational corporates. Above all, in addition to ‘patient safety’, that other secret weapon is used, namely ‘continuity of care’. Continuity of care is another chameleon wheeled out in a guise which suits its purpose at any one time.

Whilst the Blairites continue to espouse that it does not matter who is a Doctor at any one time, corporates are equally happy to use the legal stun gun of saying continuity of care will suffer if contracts are disrupted.One of the lessons from social care should have been that there are pockets of extremely poor social care, fragmented and expensive. As the next Government wishes to integrate care, with or without whole person care, one suspects that merging a means-tested system with one which isn’t will not be “no problem” as some senior health commentators have pretended. The idea that a self-directed budget where you pay for your service is “free at the point of use” is twisting the truth beyond all banality.

And these privatised contracts are neither accidental or insubstantial. One is a 10-year contract worth £1.2 billion for providing cancer services in Staffordshire, and there is also a five-year contract worth £800 million for the care of older people in Cambridge to last for the duration of the next Parliament. Both Labour and the Conservatives set in the present and previous administrations set the mood music for this, and politicians need to wipe the blood from their hands of the stains of neoliberalism. The new Jerusalem offered by private companies fraudulently (but legally) using the NHS logo has clearly run its course. Some in the UK Labour Party should be ashamed of itself for not articulating more clearly their opposition to such obscene onslaughts to the socialist founding principles of the NHS. The public clearly want a properly funded NHS. It is up to a credible party to provide that. Co-payments are a tax on the sick. Even “Pat” Hewitt, the doyenne of a previous Labour administrator, gave a speech to the London School of Economics in 2007 saying it would be madness to go down this route.

And some of the performance of companies to which the NHS has been outsourced is an insult to taxpayers, hardworking or not. Outsourcing giant Serco today announced plans to withdraw from the clinical health services market in a move precipitated by a multimillion pound loss on its NHS contracts. It is possible that Serco’s planned withdrawal could influence significantly how other private firms view the prospect of bidding for contracts involving patient facing services.

The group had already made an early exit from its contracts to provide Cornwall’s out of hours services and clinical services to Braintree Community Hospital.

Introduction of competition into the liberalised market generally has been a policy disaster of totemic proportions, producing sources of corporate fraud and misfeasance, a policy crowbar which can make mergers on the basis of clinical need unlawful, a mechanism for introducing substantial additional transaction costs, and a way of introducing private providers where profit goes into shareholders’ pockets not as surpluses in improving the service. Think tanks which aggressively pimped this have blood on their hands. And they will need to backpedal fast on their prostitution of the purchaser-provider split too.

Earlier this year, it was hailed as a success that the first private sector operator of an NHS hospital has halved its losses in the year to December. AIM-quoted Circle Holdings took over the running of Hinchingbrooke Hospital in Cambridgeshire in 2012 in a controversial part-privatisation. Private companies though wish to have their cake and eat it. They want to hide behind the cloak afforded by the Freedom of Information Act from Tony Blair’s reign. And why should the private providers get protection they haven’t earnt like a welfare claimant so despised by Iain Duncan Smith and Rachel Reeves? Private patients cannot complain to the Public Services Ombudsman for Wales unless they have received treatment commissioned and funded by the NHS. But the Welsh government has now said it has has no plans to bring private health providers within the ombudsman’s remit. Would the private sector like to contribute towards the education and training of the healthcare workforce?

This debacle from Serco, in fact, follows hot on the heels of news from Musgrove Hospital, Taunton, Somerset, where it turns out that dozens of people have been left with significant damage after undergoing operations provided by a private healthcare company at an NHS hospital. The routine cataract operations were carried out by the private provider, Vanguard Healthcare, in May to help to reduce a backlog at Musgrove Park. But the hospital’s contract with Vanguard Healthcare was terminated just a few days after thirty patients, most elderly and some frail, reported complications, including blurred vision and signs of inflammation including pain and swelling.

Laurence Vick, a medical negligence lawyer and the head of the clinical negligence team at Michelmores solicitors in Exeter, had been approached by some of the patients for whom there had clearly been a breakdown of a duty of care. Vick further said the case highlighted the “uneasy relationship” between the NHS and the private sector. He said the question of who paid – when outsourced NHS treatment – failed was of growing importance as more services were handed over to the private sector. This “uneasy relationship” which Vick refers to is likely to get massively worse as one cannot pin down who is legally accountable for failure for performance by subcontractors in “the prime contractor model”, where a main contractor can lead subcontracts for contracts say lasting ten years.

So Tony Blair was blatantly wrong: it does matter who provides NHS care. Blairites have unleashed ideological weapons of mass destruction on the Welfare State, and someone should pay the penalty for this. And it’s worse than that – you don’t know any more who’s in receipt of your taxes when you pay for what you think is the NHS. The Welfare State is being killed softly: and all English neoliberal parties have blood on their hands.

Polling firm ComRes recently found that 49% of people would be prepared to pay more tax to help fund the health service, one in three (33%) people said they would not be ready to do so, and 18% did not know either way. The public’s willingness to pay extra tax to help the NHS has reached its highest level in over a decade amid growing concern about hospitals slipping into the red, waiting lists lengthening and the service becoming unsustainable. The plan always was from the neoliberal advocates to produce a small state with low taxes, but what we have ended up is a moderate state with moderate-high taxes to fund the shareholder dividends of the outsourced companies in a range of sectors, including probation and health.

The Conservatives feel that their voters do not like ‘unfairness’ with one person obtaining an unfair advantage over another, but what we’ve got now is outsourced companies still be paid for unbelievably bad performance, and top CEOs in private providers experiencing a world nothing like their nursing counterparts in the NHS.

Labour will always try to woo the City all it wants, as per

But if disenfranchises hardworking nurses maintaining the fabric of the NHS, and brown nosing the City, it will find it does not get elected. And many socialists in Labour will not want to have blood on their hands in being part of Labour either. This because there is no obvious disinfectant yet.

All a far cry from the Spirit of ’45.

Should you pay your taxes to fund corporate welfare?

Far from reforming the NHS with a view to improving patient safety, the 493 pages of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) and the concomitant £3bn implementation produces the mechanism for awarding ‘NHS contracts’ to the private sector – an extension of corporate welfare.

Far from reforming the NHS with a view to improving patient safety, the 493 pages of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) and the concomitant £3bn implementation produces the mechanism for awarding ‘NHS contracts’ to the private sector – an extension of corporate welfare.

These private companies carry out NHS functions using a NHS logo, so as far as the ‘end user’ is concerned (formerly called ‘the patient’), the service is being run by the NHS.

This is sold as the private company running the service more efficiently,except somehow this square peg has to fit into the round hole of the fact that the private company has to provide the service at an acceptable level of profit to them. Invariably, they are awarded the contract because they are slick at making pitches.

One of the challenges for the new incoming Labour government will be getting rid of compulsory competitive tendering.

But a difficulty that the incoming government will face is not depriving all those hard-working corporate lawyers from lucrative competition and procurement law work, at a time when their revenues had been soaring and high street firms had been closing down by the day.

Another desirable move would be to ensure that contracts, awarded for ‘best value’, have some sort of ongoing performance management mechanism built in. This is because increasingly contracts of the ‘prime contractor’ variety, where various component contracts are subcontracted out, will be of a long duration. We already know from experience with various private outsourcing contracts that some companies are facing or have faced criminal investigations for fraud.

Some other companies have been directly criticised by MPs for unacceptable performance, such as the handling of welfare benefits.

One of the Dragons in Dragons Den advised in his audiobook that a good business model for ‘sustainability’ makes use of Government grants.

It follows as night follows day that all governments want to offer you low taxes. For example, a homeowner in Sussex with rising property prices with lower taxes might wish to vote Tory. Sod the food banks.

But an interesting situation is now developing where taxes are being used act as corporate welfare handouts for companies awarded outsourcing contracts in the NHS.

In this construct, working for the NHS is seen as inferior, wages in working for the NHS are lower, and there’s no pride for working for the NHS brand. But this is all sold weirdly as an ‘equality of opportunity’ to suit a competitive capitalist market.

And who would dare to rubbish the NHS brand? Let me think.

Before you attack benefit scroungers, time to think where your taxes from all your hard work are in fact going.

Keogh: Is the solution to failed outsourcing more failed outsourcing?

Sir Bruce Keogh has published a report on the first stage of his review of urgent and emergency care in England. You can read more about the review as it progresses on NHS Choices.

There are various potential causes of the current A&E problems. One reason might be that many people anecdotally seem to have trouble in getting a ‘routine’ GP appointment.

Labour says the crisis has been made worse by job cuts under this Government — such as the loss of 6,000 nursing posts since the election, and decisions to axe NHS Direct and close walk-in centres.

Sir Bruce says the current system is under “intense, growing and unsustainable pressure”. This is driven by rising demand from a population that is getting older, a confusing and inconsistent array of services outside hospital, and high public trust in the A&E brand.

Invariably, the response, from either those of are of a political inclination, or uneducated about macroeconomics, or both, is that “we cannot afford it”. This is dressed up as “sustainability”, but the actual macroeconomic definition of sustainability is being bastardised for that purpose.

Unite, which has 100,000 members in the health service, said this year that it wanted the “Pay Review Body” to “grasp the nettle” of declining living standards of NHS staff. “The idea behind the flat rate increase is that the rise in the price of a loaf of bread is the same whether you are a trust chief executive or a cleaner. Why should the CEO get a pay increase of more than ten times that of the cleaner, as would be the case if you have a percentage increase,” said Unite head of health Rachael Maskell.

According to one recent report, the boss of a failing NHS trust was awarded a £30,000 pay rise as patients were deprived of fluids and forced to wait in a car park because A&E was full. Karen Jackson, chief executive of Northern Lincolnshire and Goole Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, is reported to have accepted a 20% increase last year, taking her salary from £140,000 to £170,000.

Even if you refute that the global financial crash was due to failure of the investment banking sector, it’s impossible to deny that the current economic recovery is not being ‘felt’ by many. Indeed, some City law firms have unashamedly reported record revenues in recent years. Many well-known multi-national companies have yet further managed to avoid paying corporation tax in this jurisdiction.

Sir Bruce Keogh has himself admitted that extra money and “outsourcing” of some services to the private sector will be used to attempt to head off an immediate crisis, but will say the whole system of health care needs to be redesigned to meet growing long-term pressures.

This is on top of an estimated £3bn reorganisation of the NHS which the current Government has denied is ‘top down'; in their words, it is a ‘devolving’ reorganisation; similar to how the ‘bedroom tax’ should be a ‘spare room subsidy’ according to the Government and the BBC.

A poet who uses language far better than either the current Coalition or the BBC is Samuel Taylor-Coleridge. One of his poems, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”, relates the experiences of a sailor who has returned from a long sea voyage.

The poet uses narrative techniques such as repetition to create a sense of danger, the supernatural, or serenity, depending on the mood in different parts of the poem.

Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Nor any drop to drink.

Like the manner of this poem, the mood of the NHS changes with the repetition of certain language triggers such as ‘sustainability’.

More than £4bn of taxpayer funds was paid out last year to four of Britain’s largest outsourcing contractors – Serco, Capita, Atos and G4s – prompting concerns that controversial firms have become too big to fail, according to the National Audit Office.

But according to the National Audit Office, increasingly powerful outsourcing companies should be forced to open their books on taxpayer-funded contracts, and be subject to fines and bans from future contracts in the event that they are found to have fallen short. The report estimates that the four groups together made worldwide profits of £1.05bn, but paid between £75m and £81m in UK corporation tax. Atos and G4S are thought to have paid no tax at all.

“[This report] raises some big concerns: the quasi-monopolies that have sprung up in some parts of the public sector; the lack of transparency over profits, performance and tax paid; the inhibiting of whistleblowers; the length of contracts that taxpayers are being tied into; and the number of contracts that are not subject to proper competition,” said Margaret Hodge, chair of the public accounts committee, who commissioned the NAO to carry out the study.

As for the NHS, Keogh describes it as ‘complete nonsense’ that his proposals are a ‘downgrading’ or ‘two tier system’. As an example, Keogh says there has been 20% increased survival rate in major trauma by treatment in a specialist treatment on the basis of his 25 designated trauma centres. Keogh’s focus is on major trauma, stroke or heart attack.

This is a perfectly reasonable observation, in the same way that the existence of the tertiary referral medicine centres for clinical medicine, such as the Brompton, the Royal Marsden or Queen Square, for highly specialist medical management of respiratory, palliative and neurological medicine should not be interpreted as the NHS Foundation Trust ‘tier’ offering a second-rate service on rare conditions. Developed after an extensive engagement exercise, the new report proposes a new blueprint for local services across the country that aims to make care more responsive and personal for patients, as well as deliver even better clinical outcomes and enhanced safety.

Keogh advocates a system-wide transformation over the next three to five years, saying this is “the only way to create a sustainable solution and ensure future generations can have peace of mind that, when the unexpected happens, the NHS will still provide a rapid, high quality and responsive service free at the point of need.”

But it is highly significant that this ‘beefed up system’ is building on the rocky foundation for the NHS since May 2010, where the Coalition has ‘liberalised the market’. Far from giving the NHS certainty, the Health and Social Care Act (2012), as had been widely anticipated, has liberated anarchy and chaos.

There are many more private providers delivering profit for their shareholders.

However, the National Health Service has been propelled at high speed into a fragmented, disjointed service with numerous providers not sharing critical information with each other let alone the public.

Only this week, Grahame Morris, Labour MP for Easington, warned yet again about how private providers are able to hide behind the ‘commercial sensitivity’ corporate veil when it comes to freedom of information act requests. This wouldn’t be so significant if it were not for the fact that ‘beefing up’ the NHS 111 system is such a big part of Keogh’s plan.

NHS 111 was launched in a limited number of regions in March 2013 ahead of a planned national launch in April 2013. This initial launch was widely reported to be a failure. Prior to the launch the British Medical Association – affectionately referred to by the BBC as “The Doctors’ Union” – had sufficient concern to write to the Secretary of State for Health requesting that the launch be postponed. On its introduction, the service was unable to cope with demand; technical failures and inadequate staffing levels led to severe delays in response (up to 5 hours), resulting in high levels of use of alternative services such as ambulances and emergency departments. The public sector trade union UNISON had also recommended delaying the full launch.

The service has run by different organisations in different parts of the country, with private companies, local ambulance services and NHS Direct, which used to operate the national non-emergency phone line, all taking on contracts last year. The problems led to the planned launch date being abandoned in South West England, London and Midlands (England). In Worcestershire, the service was suspended one month after its launch in order to prevent patient safety being compromised. The 111 non-emergency service has faced criticism since a trial was launched in parts of England last month. Some callers said they had struggled to get through or left on hold for hours.

Andy Burnham, Labour’s shadow health secretary, at the time accused the Government of destroying NHS Direct, “a trusted, national service” in an “act of vandalism”. “It has been broken up into 46 cut-price contracts,” he said. “Computers have replaced nurses and too often the computer says ‘go to A&E’.”

Clare Gerada, also at the time, said that the introduction of 111 had “destabilised” a system that was functioning well under NHS Direct and called for non-emergency phone services to be operated in closer collaboration with local GP services.

“The big problem about 111 is of course money,” she said. “It was the lowest bidders on the whole that won the contracts… If you pay £7 a call versus £20 a call you don’t have to be an economist to see that something’s going to be sacrificed. What’s sacrificed is clinical acumen.”

Keogh is keen to put a different gloss on the situation now. He admits that people wish to talk to clinician if they are worried, rather than an “unqualified call handler”. He says that this is possible ‘but we need to put the infomatics in place’. 40% of patients need reassurance, according to Keogh. Keogh then argues that, if there is a concern, an ambulance can be called up, or a GP appointment can be arranged.

However, for this system to work, people offering out-of-hours services will not just be dealing with a third degree burn in the absence of any previous medical history at all. There will be patients with long-term conditions like diabetes, asthma and chronic heart disease, who might not have to use A&E services so frequently if they were supported to manage their health more effectively.

Some of these patients will be ‘fat filers’, where it’s impossible to know what a medical presentation might be without access to complex medical notes; e.g. a cold in a profoundly immunosuppressed individual is an altogether different affair to a cold in a healthy individual. Likewise, individuals with specific social care needs will need to be recognised in any out-of-hours service.

The aim of ‘beefing up’, as Keogh puts it, the ‘National Health Service’ was to make it a coherent service across all disciplines, with clinicians – as well as top CEOs – adequately resourced out of general taxation.

As it is, it is pouring more money into people who have not delivered the goods thus far.

The solution to failed outsourcing cannot be more failed outsourcing. As one interesting article in ‘Computer Weekly’ explained recently, the “NHS 111 chaos is a warning to organisations outsourcing”.

The report has also made a case for improved training and investment in community and ambulance services, so that paramedics provide more help at the scene of an incident, with nurses and care workers dispatched to offer support in the home, so fewer patients are taken to hospital. This can work extremely well, provided that resources are allocated to such services first, and there is a proven improvement in quality (which seems very likely.)

And if somebody tells you it’s all about sustainability – tell them there’s water water everywhere, and there’s not a drop to drink as this recent event provoked.

The “NHS prime contractor model”: why the legal liability of subcontractors matters

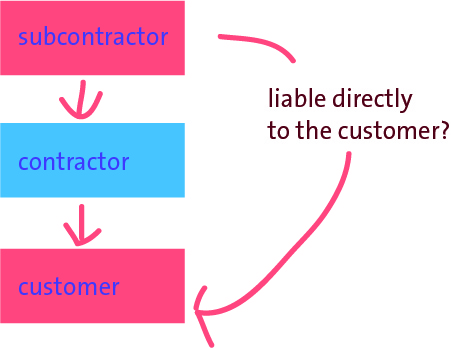

At a time when “every penny counts”, it seems rather disgusting that thousands and millions of pounds should be diverted from frontline care (which we apparently can’t afford judging by the cuts in nursing jobs) to the commercial and corporate lawyers. Management consultants, politicians and staff in CCGs have no expertise in commercial law. Now that it turns out that commissioners could be freed to award work to a “prime contractor” over five to 10 years from 2014-15, according to the Department of Health, the issue of what happens if a subcontractor commits an offence in tort (negligence) or contract (breach of contract) is highly significant. The subcontractor’s damage could cause loss to the ultimate patient. Instead, commissioning pitches are full of inane garbage such as, “we need to do much better with much less“, when you consider that £20bn efficiency savings, aided and abetted by cuts in nursing staffing, is dwarfed by the new £80bn cost of #HS2. It is reported, for example, in the Health Services Journal, that,

At a time when “every penny counts”, it seems rather disgusting that thousands and millions of pounds should be diverted from frontline care (which we apparently can’t afford judging by the cuts in nursing jobs) to the commercial and corporate lawyers. Management consultants, politicians and staff in CCGs have no expertise in commercial law. Now that it turns out that commissioners could be freed to award work to a “prime contractor” over five to 10 years from 2014-15, according to the Department of Health, the issue of what happens if a subcontractor commits an offence in tort (negligence) or contract (breach of contract) is highly significant. The subcontractor’s damage could cause loss to the ultimate patient. Instead, commissioning pitches are full of inane garbage such as, “we need to do much better with much less“, when you consider that £20bn efficiency savings, aided and abetted by cuts in nursing staffing, is dwarfed by the new £80bn cost of #HS2. It is reported, for example, in the Health Services Journal, that,

“If the £120m deal is finalised, Circle ? which also runs Hinchingbrooke Health Care Trust ? will be financially and clinically accountable to commissioners for the whole pathway.”

but forgetting the spin (and one should really do that in the best interest of patients), this cannot be true if the subcontractors are excluded from liability under English law.

A useful starting point is the NHS Commissioning Board’s own “The NHS Standard Contract: a guide for clinical commissioners.”

This instrument defines the “prime contractor” as follows:

“Contract with prime contractor who is responsible for management and delivery of whole care pathway, with parts of care pathway subcontracted to other providers (Prime Contractor model). The prime contractor may not be the largest provider in the pathway but the role is focused on the pathway service delivery”.

However, the document perpetuates the notion of subcontractors’ accountability which the English Courts are likely to have difficulty with:

“The commissioner retains accountability for the services commissioned but is reliant on the prime contractor to hold subcontractors to account.”

Understanding both the management principles about the safety culture in management and the legal implications of subcontracting converges on one particular industry: the construction industry. A main contractor may engage another person in order for that subcontractor to undertake a specific part of the main contractor’s works. Subcontracting is favoured in the house building industry because it offers main contractors flexibility and cost efficiencies (Ireland, 1988). However, parallels are confounded by the fact that commissioning NHS services is not the same as making buildings, the lessons from different jurisdictions are different, the degree of ‘commerciality’ of the actual contract (e.g. residential building can even be different from corporate building), the actual material facts of how close the parties are legally vary, subtle differences in the nature of contractual terms, the finding that the nature of loss may not be the same, and so it goes on. It is increasingly clear from any rudimentary analysis that the subcontractor cannot be easily accountable to the patient at all, because of a number of well settled legal principles.

A study of safety culture among subcontractors in the domestic housing construction industry using in depth semi structured interviews with 11 subcontractors from six different trades by Phil Wadick from Bellingen, Australia found that subcontractors place an enormous amount of trust in their own common sense to help inform their safety judgements and decisions (Wadick et al., 2010). According to their study, subcontractors have a deep respect and trust for the safety knowledge gained from years of practice, and a distrust of safety courses that attempt to privilege paper/procedural knowledge over practical, embedded and embodied safety knowledge.

In the law of tort, a party does not need to have a contract with another to be liable directly to that party in negligence. The legal principle of privity of contract, as stated below from Treitel, does not preclude third parties from suing contracting parties in tort.

“The doctrine of privity of contract means that a contract, as a general rule, confer rights or impose impositions arising under it on any person except the parties to it.” (GH Treitel, “The Law of Contract”)

This privity of contract is the root cause of the personal tragedy depicted in this video from the US jurisdiction, of Wendell Potter and Nataline Sarkisian: there is no direct contract between insurer and insuree.

You can see the smoking gun all too easy for this jurisdiction, where the CCGs are state insurance schemes. In England, there’s no contract between patient and provider, but only between provider and CCG and (implicitly) between CCG and NHS England. As stated correctly by Nicholas Gould, a Partner in Fenwick Ellott (the largest construction and energy law firm in the UK), there is no direct contractual link between the employer and the subcontractor by virtue of the main contract for the construction scenario. In other words, the main contractor is not the agent of the employer and conversely the employer’s rights and obligations are in respect of the main contractor only. The employer therefore cannot sue the subcontractor in the event that the subcontractor’s work is defective, is lacking in quality, or delays the works. The subcontractor situation therefore merits some particular scrutiny in the law of tort, where it is necessary to establish a breach of a duty of care, with sufficient cauality, to prove negligence on the balance of probabilities.

Typically, in their contracts, the “prime contractor” will limit its liability to a customer to a patient ultimately, and in turn the subcontractor will limit its liability to the prime contractor. In the 2004 case of Rolls-Royce New Zealand Ltd v Carter Holt Harvey Ltd [2004] NZCA 97; [2005] 1 NZLR 324 (23 June 2004) “Rolls Royce”, the Court of Appeal of New Zealand decided that the subcontractor in that construction case could not be liable to the customer. In Rolls Royce, the Court of Appeal said that whether or not a duty of care should be recognised in New Zealand depended on whether, in all the circumstances, it was just and reasonable that such a duty is imposed. This, in turn, involves two broad fields of inquiry. First is the degree of proximity or relationship between the parties, and second is whether there are any wider policy considerations that might negate or restrict or strengthen the existence of a duty in any particular class of case.

But can a duty-of-care by the subcontractor be held in tort in the English law? The House of Lords attempted to establish a general duty of care in respect of pure economic loss resulting from a negligent act, based on the closeness of the relationship between the parties and reliance by the claimants on the defendants’ skill and experience, in Junior Books Ltd v Veitchi Co Ltd [1982] UKHL 4 (15 July 1982). This Scottish case represents the high water mark for liability in tort for subcontractors to employers in respect of negligence. In this case a contractor was engaged to construct a factory for the building owner. The defendant subcontractors were engaged to lay a specialist composite floor. The floor was defective and began to crack almost immediately. However, there was no danger to the health and safety of the occupants, nor any danger to other property of the building owner. Regardless, the floor needed replacement because of the defects. There was no direct contract between the employer and the subcontractor, but the building owner sought the costs of replacement and loss of profit while the flooring was being relayed from the subcontractor, and succeeded in the House of Lords. Lord Keith of Kinkel advised about the need to avoid extrapolating too widely from the ratio of this case:

But can a duty-of-care by the subcontractor be held in tort in the English law? The House of Lords attempted to establish a general duty of care in respect of pure economic loss resulting from a negligent act, based on the closeness of the relationship between the parties and reliance by the claimants on the defendants’ skill and experience, in Junior Books Ltd v Veitchi Co Ltd [1982] UKHL 4 (15 July 1982). This Scottish case represents the high water mark for liability in tort for subcontractors to employers in respect of negligence. In this case a contractor was engaged to construct a factory for the building owner. The defendant subcontractors were engaged to lay a specialist composite floor. The floor was defective and began to crack almost immediately. However, there was no danger to the health and safety of the occupants, nor any danger to other property of the building owner. Regardless, the floor needed replacement because of the defects. There was no direct contract between the employer and the subcontractor, but the building owner sought the costs of replacement and loss of profit while the flooring was being relayed from the subcontractor, and succeeded in the House of Lords. Lord Keith of Kinkel advised about the need to avoid extrapolating too widely from the ratio of this case:

“Having thus reached a conclusion in favour of the respondents upon the somewhat narrow ground which I have indicated. I do not consider this to be an appropriate case for seeking to advance the frontiers of the law of negligence upon the lines favoured by certain of your Lordships. There are a number of reasons why such an extension would, in my view, be wrong in principle.”

The courts began, however, to retreat from the implications of Junior Books almost immediately. The leading speech was given by Lord Roskill and he based his analysis on Lord Wilberforce’s infamous two stage test for establishing a duty of care set out in Anns v Merton London Borough Council [1977] UKHL 4 (12 May). This approach was of course overruled in Murphy v Brentwood District Council [1990] UKHL 2 (26 July). In Southern Water Authority v Carey [1985] 2 All ER 1077, the work was defective and the entire sewerage scheme failed. The Authority sued the subcontractor in negligence, and yet the High Court decided that the subcontractor was not liable in tort as a result of the terms of the main contract.

Nonetheless, there are a variety of general principles applicable to subcontractor relationships. First, the main contractor remains responsible to the employer for a number of diverse aspects of the subcontract. In other words, the main contractor is still responsible for time, quality and paying the subcontractor in accordance with the contract between the main contractor and subcontractor regardless of any issue that could arise between the main contractor and the employer. This will of course depend upon the terms of the contract between the main contractor and a subcontractor, and might also depend on the separate contract between the employer and main-contractor. However, they are nonetheless two separate contracts, and the legal doctrine of privity of contract applies in this jurisdiction as in many jurisdictions for the “prime contractor model”, and the matching or integration of similar “back to back” obligations is often unsatisfactory. Clever drafting can even lead to the subcontractors escaping liability altogether. For example, quite recently, it is reported that a dredging subcontractor, Van Oord, escaped liability for the design of dredging works due to the exclusion clause in its tender (Mouchel Ltd. v Van Oord (UK) Ltd., [2011] EWHC 72).

With all this uncertainty, it is quite unhelpful that there is also much uncertainty about how a subcontractor will have been deemed to have ‘failed': the so-called “outcomes-based commissioning“. It could be that there could also be patient feedback indicators built into the deal, which commissioners hope will enable them to hold the lead provider to account if people’s experience of services suffers. “Soft intelligence” from GPs could also be used. The legal cases will certainly turn on their own material facts, but, with a time window which could be as large as 10-15 years and with fairly strong private providers financially (important for business continuity), it is likely that the English law courts will be asked at some stage to decide upon whether the subcontractor can be legally ‘accountable’ to the patient. The answer is very likely to be “no”, and there will be then many very angry intelligent people who will feel that they simply have been misled. A lot of liability rests with the CCG accountable officer position – but if all goes wrong such officers can simply move onto other well-paid jobs in other sectors. When you consider the death of legal aid for clinical negligence, some might say this a real mess.

Not to worry – it’s business as usual.

Further reading

Ireland, V. (1988), Improving Work Practices in the Australian Building Industry. A Comparison with the UK and USA, Master Builders Federation of Australia.

Wadick, P (2010), Safety culture among subcontractors in the domestic housing construction industry, Structural SurveyVol. 28 No. 2, pp. 108-120

Outsourcing has become a policy drug, and they need to kick the habit

If you don’t want to do something, you pay somebody else to do it. Hopefully you pay them peanuts. Doesn’t matter if the actual product or service is a bit shit. Or you could allow somebody else to do it under your identity still. Everyone thinks you’re the author it. But you pay that person a massive mark up so they make a tidy profit. Everyone’s a winner.

For this Government under Frances Maude, Chris Grayling and Jeremy Hunt, “outsourcing” is a drug. They need more of it to get the same kick (an increasing degree of tolerance), and if they don’t outsource something they get nasty withdrawal symptoms. Outsourcing is consider a useful step along the way to privatisation, and of course many less intelligent people have been arguing that the Health and Social Care Act is not privatisation. It is clearly privatisation if you outsource what should be a state-run health service into private hands for profit or surplus, and it is privatisation if you allow up to 50% of income to come from private sources. Both are new developments under this Government. Everyone’s a winner here – especially the hedge funds who are the major institutional shareholders of the private healthcare companies, the private companies who can find through slick procurement bids willing funders, and, of course management consultants, accountants and lawyers who can send a NHS Trust into one of the many detailed insolvency and failure régimes outlined in the Health and Social Care Act (2012). Mind you, there’s not a single clause on ‘safe staffing requirements’ in NHS Trusts, as a necessary and proportionate ‘check and balance’ on overzealous managers inflicting ‘efficiency cuts’ to frontline doctors and nurses. “More for less” is the mantra, and, with the Secretary of State now legally not obligated for the NHS for the first time (but responsible for ‘special measures’ presumably so that he can take control of both lack of patient safety in extreme measures and which private sector advisors can advise), outsourcing is not the next scandal waiting to happen. It is well and truly alive. While the ideological concern has been ‘privatising profits, socialising losses’ a concept coined by Andrew Jackson as far back as 1834 (and maybe the Royal Mail and RSB may be worthy examples to consider here), there is now an added dimension that foreign multinationals can raid the NHS, take over vast bits of it, and their registered offices for tax reasons might be abroad. The line of attack has always been that Doctors and nurses contribute nothing to the ‘wealth’ of this country not being wealth creators (footballers possibly do contribute more in a similar way to “Top Gear” by being potent foreign merchandising exports inter alia). The massive irony is that the tax from profits ends up in foreign jurisdictions, and contribute to the economy of those countries not ours. The resolution of the US-EU Free Trade Agreement, which may or may not include the NHS, will be important here, and there’s still no answer to Debbie Abrahams’ inquiry to my knowledge:

Debbie Abrahams (Oldham East and Saddleworth) (Lab): Will the Prime Minister confirm that the NHS is exempt from the EU-US trade negotiations?

The Prime Minister: I am not aware of a specific exemption for any particular area, but I think that the health service would be treated in the same way in relation to EU-US negotiations as it is in relation to EU rules. If that is in any way inaccurate, I will write to the hon. Lady and put it right.

In an article by Patrick Wintour published recently, Cruddas describes a ‘modern anomie’, a breakdown between an individual and his or her community, and alludes to the challenge of institutions mediating globalisation. Cruddas also describes something which I have heard elsewhere, from Lord Stewart Wood, of a more ‘even’ creation of wealth, whatever this means about the even ‘distribution’ of wealth. One of the lasting legacies of the first global financial crisis is how some people have done extremely well, possibly due to their resilience in economic terms. For example, it has not been unusual for large corporate law firms to maintain a high standard of revenues, while high street law has come close to total implosion in some parts of the country. In a way, this reflects a shift from pooling resources in the State to a neoliberal free market model. The global financial crash did not see a widespread rejection of capitalism, although the Occupy movement did gather some momentum (especially locally here in St. Paul’s Cathedral). It produced glimpses of nostalgia for ‘the spirit of ’45”, but was used effectively by Conservative and libertarian political proponents are causing greater efficiencies. Indeed, Marks and Spencer laid off employees, in its bid to decrease the decrease in its profits, and this corporate restructuring was not unusual. A conservative and a libertarian have several things in common, the most important is the need for people to take care of themselves for the most part. Libertarians want to abolish as much government as they practically can. It is thought that the majority of libertarians are “minarchists” who favour stripping government of most of its accumulated power to meddle, leaving only the police and courts for law enforcement and a sharply reduced military for national defence. A minority are possibly card-carrying anarchists who believe that “limited government” is a delusion, and the free market can provide better law, order, and security than any goverment monopoly.

Essentially a libertarian would fund public services by privatising them. In this ‘brave new world’, insurance companies could use the free market to spread most of the risks we now “socialise” through government, and make a profit doing so. That of course would be the ideal for many in reducing the spend on the NHS, to produce a rock-bottom service with minimal cost for the masses. And to give them credit, the Health and Social Care Act was the biggest Act of parliament, that nobody voted for, to outsource the operations of the NHS to the private sector, which falls under the rubric of privatisation. Outsourcing is an arrangement in which one company provides services for another company that could also be or usually have been provided in-house. Outsourcing is a trend that is becoming more common in information technology and other industries for services that have usually been regarded as intrinsic to managing a business, or indeed the public sector. Many expected the election of the present government to herald a more determined approach to outsourcing public services to the private sector. Initially came the idea of the “big society”, with its emphasis on creating and using more social enterprises to deliver public services, but the backers for this new era of venture philanthropism were not particularly forthcoming. The PR of it, through Steve Hilton and colleagues, was disastrous, and even Lord Wei, one of its chief architects, left. No one in the UK likes the idea of domestic jobs moving overseas. But in recent years, the U.K. has accepted the outsourcing of tens of thousands of jobs, and many prominent corporate executives, politicians, and academics have argued that we have no choice, that with globalisation it is critical to tap the lower costs and unique skills of labour abroad to remain competitive. They argue that Government should stay out of the way and let markets determine where companies hire their employees. But is this debate ever held in public? No, there was always a problem with reconciling the need for cuts with an ideological thirst for cutting the State. Here in the UK, in 2010, the government indicated that it wanted to see new entrants into the outsourcing market, and the prime minister visited Bangalore, the heart of India’s IT and outsourcing industry, for high profile meetings with chief executives of companies such as TCS, Infosys, HCL and Wipro. Nobody ever bothers to ask the public what they think about outsourcing, but if Gillian Duffy’s interaction with Gordon Brown is anything to go by, or Nigel Farage’s baptism in the local elections has proved, the public is still resistant to a concept of ‘British jobs for foreign workers’. However, it is still possible that the general public are somewhat indifferent to screw-ups of outsourcing from corporates, in the same way they learn to cope with excessive salaries of CEOs in the FTSE100. The media have trained us to believe that unemployment rights do not matter, and this indeed has been a successful policy pursued by the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. People do not appear to blame the Government for making outsourcing decisions, for example despite the fact that the ATOS delivery of welfare benefits claims processing has been regarded by many as poor, the previous Labour government does not seem to be blamed much for the current fiasco, and the current fiasco has not become a major electoral issue yet.

And the list of screw-ups is substantial. G4S – the firm behind the Olympic security fiasco – has nowbeen selected to support the Police Service of Northern Ireland at the G8 Summit next month. Despite the company’s botched handling of the Olympics Games contract last summer, G4S has been chosen to supply 450 security staff for the event at Lough Erne, County Fermanagh The leaders of the world’s eight wealthiest countries are expected in Fermanagh on June 17 and 18. Meanwhile, medical assessments of benefit applicants at Atos Healthcare were designed to incorrectly assess claimants as being fit for work, according to an allegation of one of the company’s former senior doctors has claimed. Greg Wood, a GP who worked at the company as a senior adviser on mental health issues, said claimants were not assessed in an “even-handed way”, that evidence for claims was never put forward by the company for doctors to use, and that medical staff were told to change reports if they were too favourable to claimants. Elsewhere, Scotland’s hospitals were banned from contracting out cleaning and catering services to private firms as part of a new drive towards cutting the spread of deadly superbugs in the NHS. There were 6,430 cases of C. difficile infections in Scotland in one year recently, of which 597 proved fatal. The problem was highlighted by an outbreak of the infection earlier this year at the Vale of Leven hospital in Dunbartonshire which affected 55 people. The infection was identified as either the cause of, or a contributory factor in, the death of 18 patients.

Whatever our perception of the public perception, the impact on transparency and strong democracy merit consideration. As we outsource any public service, we appear to risk removing it from the checks and balances of good governance that we expect to have in place. Expensive corporate lawyers can easily outmanoeuvre under-resourced government departments, who often appear to be unaware of the consequences, and this of course is the nightmare scenario of the implementation of the section 75 NHS regulations. Even talking domestically, where contracts privilege commercial sensitivities over public rights, they can be used to exclude the provision of open data or to exempt the outsourcer from freedom of information requests. Talking globally, “competing in the global race” has become the buzzword for allowing UK companies to outsource to countries that do not have laws (or do not enforce laws) for environmental protection, worker safety, and/or child labour. However, all of this is to be expected from a society that we are told wants ‘less for more’, but then again we never have this debate. Are the major political parties afraid to talk to us about outsourcing? Yes, and it could be related to that other ‘elephant in the room’, about whether people would be willing to pay their taxes for a well-run National Health Service, where you would not be worried about your local A&E closing in the name of QUIPP (see this blogpost ). Either way, Jon Cruddas is right, I feel; the ‘modern anomie’ is the schism between the individual and the community, and maybe what Margaret Thatcher in fact meant was ‘There is no such thing as community’. If this means that Tony Blair feels that ‘it doesn’t matter who supplies your NHS services’, and we then get invasion of the corporates into the NHS, you can see where thinking like this ultimately ends up.

Politically, outsourcing vast amounts of the National Health Service is a big mistake. Take for example the scenario of what happens when something goes wrong. Will you get your money back? The lack of responsibility of the private sector shows how the NHS has to bail out the surgical mistakes of PIP breast implants. The State, evil though it is, does make a habit however of bailing out the private sector, as we all remember from the £860 bailout for the banking industry. It seems like a ‘cost saving’, but it clearly isn’t, in the same way that the private finance initiative has become a ‘cash cow’ for corporates. The essence of NHS policy is not to let the policy lunatics take over, in this case people with clearly vested interests having more impact on policy than professionals in the field. Part of the problem is that there is a lot more in common for Conservative and Labour policies, and indeed this is contributing to a growing sentiment that Labour is becoming complacent on the NHS (tweet by @gabyhinsliff):

Time will tell whether such fears will indeed materialise.

Outsourcing and the "modern anomie"

Jon Cruddas recently gave a progress report on how the evolution of ‘One Nation’ policy was going, In an article by Patrick Wintour published yesterday, Cruddas describes a ‘modern anomie’, a breakdown between an individual and his or her community, and alludes to the challenge of institutions mediating globalisation. Cruddas also describes something which I have heard elsewhere, from Lord Stewart Wood, of a more ‘even’ creation of wealth, whatever this means about the even ‘distribution’ of wealth. One of the lasting legacies of the first global financial crisis is how some people have done extremely well, possibly due to their resilience in economic terms. For example, it has not been unusual for large corporate law firms to maintain a high standard of revenues, while high street law has come close to total implosion in some parts of the country. In a way, this reflects a shift from pooling resources in the State to a neoliberal free market model.

The global financial crash did not see a widespread rejection of capitalism, although the Occupy movement did gather some momentum (especially locally here in St. Paul’s Cathedral). It produced glimpses of nostalgia for ‘the spirit of ’45”, but was used effectively by Conservative and libertarian political proponents are causing greater efficiencies. Indeed, Marks and Spencer laid off employees, in its bid to decrease the decrease in its profits, and this corporate restructuring was not unusual. A conservative and a libertarian have several things in common, the most important is the need for people to take care of themselves for the most part. Libertarians want to abolish as much government as they practically can. It is thought that the majority of libertarians are “minarchists” who favour stripping government of most of its accumulated power to meddle, leaving only the police and courts for law enforcement and a sharply reduced military for national defence. A minority are possibly card-carrying anarchists who believe that “limited government” is a delusion, and the free market can provide better law, order, and security than any goverment monopoly.

Essentially a libertarian would fund public services by privatising them. In this ‘brave new world’, insurance companies could use the free market to spread most of the risks we now “socialise” through government, and make a profit doing so. That of course would be the ideal for many in reducing the spend on the NHS, to produce a rock-bottom service with minimal cost for the masses. And to give them credit, the Health and Social Care Act was the biggest Act of parliament, that nobody voted for, to outsource the operations of the NHS to the private sector, which falls under the rubric of privatisation. Outsourcing is an arrangement in which one company provides services for another company that could also be or usually have been provided in-house. Outsourcing is a trend that is becoming more common in information technology and other industries for services that have usually been regarded as intrinsic to managing a business, or indeed the public sector.

Many expected the election of the present government to herald a more determined approach to outsourcing public services to the private sector. Initially came the idea of the “big society”, with its emphasis on creating and using more social enterprises to deliver public services, but the backers for this new era of venture philanthropism were not particularly forthcoming. The PR of it, through Steve Hilton and colleagues, was disastrous, and even Lord Wei, one of its chief architects, left. No one in the UK likes the idea of domestic jobs moving overseas. But in recent years, the U.K. has accepted the outsourcing of tens of thousands of jobs, and many prominent corporate executives, politicians, and academics have argued that we have no choice, that with globalisation it is critical to tap the lower costs and unique skills of labor abroad to remain competitive. They argue that Government should stay out of the way and let markets determine where companies hire their employees. But is this debate ever held in public? No, there was always a problem with reconciling the need for cuts with an ideological thirst for cutting the State. Unfortunately, cutting the State was cognitively dissonant with cutting the ‘safety net’ of welfare, which is why the rhetoric on scroungers had to be ‘upped’ in recent years by the UK media (please see original source in ‘Left Foot Forward’). And so it came to be, the Compassionate era of Conservatism came to pass.

Here in the UK, in 2010, the government indicated that it wanted to see new entrants into the outsourcing market, and the prime minister visited Bangalore, the heart of India’s IT and outsourcing industry, for high profile meetings with chief executives of companies such as TCS, Infosys, HCL and Wipro. Nobody ever bothers to ask the public what they think about outsourcing, but if Gillian Duffy’s interaction with Gordon Brown is anything to go by, or Nigel Farage’s baptism in the local elections has proved, the public is still resistant to a concept of ‘British jobs for foreign workers’. However, it is still possible that the general public are somewhat indifferent to screw-ups of outsourcing from corporates, in the same way they learn to cope with excessive salaries of CEOs in the FTSE100. The media have trained us to believe that unemployment rights do not matter, and this indeed has been a successful policy pursued by the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. People do not appear to blame the Government for making outsourcing decisions, for example despite the fact that the ATOS delivery of welfare benefits claims processing has been regarded by many as poor, the previous Labour government does not seem to be blamed much for the current fiasco, and the current fiasco has not become a major electoral issue yet.

And the list of screw-ups is substantial. G4S – the firm behind the Olympic security fiasco – has nowbeen selected to support the Police Service of Northern Ireland at the G8 Summit next month. Despite the company’s botched handling of the Olympics Games contract last summer, G4S has been chosen to supply 450 security staff for the event at Lough Erne, County Fermanagh The leaders of the world’s eight wealthiest countries are expected in Fermanagh on June 17 and 18. Meanwhile, medical assessments of benefit applicants at Atos Healthcare were designed to incorrectly assess claimants as being fit for work, according to an allegation of one of the company’s former senior doctors has claimed. Greg Wood, a GP who worked at the company as a senior adviser on mental health issues, said claimants were not assessed in an “even-handed way”, that evidence for claims was never put forward by the company for doctors to use, and that medical staff were told to change reports if they were too favourable to claimants. Elsewhere, Scotland’s hospitals were banned from contracting out cleaning and catering services to private firms as part of a new drive towards cutting the spread of deadly superbugs in the NHS. There were 6,430 cases of C. difficile infections in Scotland in one year recently, of which 597 proved fatal. The problem was highlighted by an outbreak of the infection earlier this year at the Vale of Leven hospital in Dunbartonshire which affected 55 people. The infection was identified as either the cause of, or a contributory factor in, the death of 18 patients.

Whatever our perception of the public perception, the impact on transparency and strong democracy merit consideration. As we outsource any public service, we appear to risk removing it from the checks and balances of good governance that we expect to have in place. Expensive corporate lawyers can easily outmanoeuvre under-resourced government departments, who often appear to be unaware of the consequences, and this of course is the nightmare scenario of the implementation of the section 75 NHS regulations. Even talking domestically, Where contracts privilege commercial sensitivities over public rights, they can be used to exclude the provision of open data or to exempt the outsourcer from freedom of information requests. Talking globally, “competing in the global race” has become the buzzword for allowing UK companies to outsource to countries that do not have laws (or do not enforce laws) for environmental protection, worker safety, and/or child labour. However, all of this is to be expected from a society that we are told wants ‘less for more’, but then again we never have this debate. Are the major political parties afraid to talk to us about outsourcing? Yes, and it could be related to that other ‘elephant in the room’, about whether people would be willing to pay their taxes for a well-run National Health Service, where you would not be worried about your local A&E closing in the name of QUIPP (see this blogpost by Dr Éoin Clarke). Either way, Jon Cruddas is right, I feel; the ‘modern anomie’ is the schism between the individual and the community, and maybe what Margaret Thatcher in fact meant was ‘There is no such thing as community’. If this means that Tony Blair feels that ‘it doesn’t matter who supplies your NHS services’, and we then get invasion of the corporates into the NHS, you can see where thinking like this ultimately ends up.

Outsourcing, NHS, and the “modern anomie”

Jon Cruddas recently gave a progress report on how the evolution of ‘One Nation’ policy was going, In an article by Patrick Wintour published yesterday, Cruddas describes a ‘modern anomie’, a breakdown between an individual and his or her community, and alludes to the challenge of institutions mediating globalisation. Cruddas also describes something which I have heard elsewhere, from Lord Stewart Wood, of a more ‘even’ creation of wealth, whatever this means about the even ‘distribution’ of wealth. One of the lasting legacies of the first global financial crisis is how some people have done extremely well, possibly due to their resilience in economic terms. For example, it has not been unusual for large corporate law firms to maintain a high standard of revenues, while high street law has come close to total implosion in some parts of the country. In a way, this reflects a shift from pooling resources in the State to a neoliberal free market model.

The global financial crash did not see a widespread rejection of capitalism, although the Occupy movement did gather some momentum (especially locally here in St. Paul’s Cathedral). It produced glimpses of nostalgia for ‘the spirit of ’45”, but was used effectively by Conservative and libertarian political proponents are causing greater efficiencies. Indeed, Marks and Spencer laid off employees, in its bid to decrease the decrease in its profits, and this corporate restructuring was not unusual. A conservative and a libertarian have several things in common, the most important is the need for people to take care of themselves for the most part. Libertarians want to abolish as much government as they practically can. It is thought that the majority of libertarians are “minarchists” who favour stripping government of most of its accumulated power to meddle, leaving only the police and courts for law enforcement and a sharply reduced military for national defence. A minority are possibly card-carrying anarchists who believe that “limited government” is a delusion, and the free market can provide better law, order, and security than any goverment monopoly.

Essentially a libertarian would fund public services by privatising them. In this ‘brave new world’, insurance companies could use the free market to spread most of the risks we now “socialise” through government, and make a profit doing so. That of course would be the ideal for many in reducing the spend on the NHS, to produce a rock-bottom service with minimal cost for the masses. And to give them credit, the Health and Social Care Act was the biggest Act of parliament, that nobody voted for, to outsource the operations of the NHS to the private sector, which falls under the rubric of privatisation. Outsourcing is an arrangement in which one company provides services for another company that could also be or usually have been provided in-house. Outsourcing is a trend that is becoming more common in information technology and other industries for services that have usually been regarded as intrinsic to managing a business, or indeed the public sector.

Many expected the election of the present government to herald a more determined approach to outsourcing public services to the private sector. Initially came the idea of the “big society”, with its emphasis on creating and using more social enterprises to deliver public services, but the backers for this new era of venture philanthropism were not particularly forthcoming. The PR of it, through Steve Hilton and colleagues, was disastrous, and even Lord Wei, one of its chief architects, left. No one in the UK likes the idea of domestic jobs moving overseas. But in recent years, the U.K. has accepted the outsourcing of tens of thousands of jobs, and many prominent corporate executives, politicians, and academics have argued that we have no choice, that with globalisation it is critical to tap the lower costs and unique skills of labor abroad to remain competitive. They argue that Government should stay out of the way and let markets determine where companies hire their employees. But is this debate ever held in public? No, there was always a problem with reconciling the need for cuts with an ideological thirst for cutting the State. Unfortunately, cutting the State was cognitively dissonant with cutting the ‘safety net’ of welfare, which is why the rhetoric on scroungers had to be ‘upped’ in recent years by the UK media (please see original source in ‘Left Foot Forward’). And so it came to be, the Compassionate era of Conservatism came to pass.

Here in the UK, in 2010, the government indicated that it wanted to see new entrants into the outsourcing market, and the prime minister visited Bangalore, the heart of India’s IT and outsourcing industry, for high profile meetings with chief executives of companies such as TCS, Infosys, HCL and Wipro. Nobody ever bothers to ask the public what they think about outsourcing, but if Gillian Duffy’s interaction with Gordon Brown is anything to go by, or Nigel Farage’s baptism in the local elections has proved, the public is still resistant to a concept of ‘British jobs for foreign workers’. However, it is still possible that the general public are somewhat indifferent to screw-ups of outsourcing from corporates, in the same way they learn to cope with excessive salaries of CEOs in the FTSE100. The media have trained us to believe that unemployment rights do not matter, and this indeed has been a successful policy pursued by the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. People do not appear to blame the Government for making outsourcing decisions, for example despite the fact that the ATOS delivery of welfare benefits claims processing has been regarded by many as poor, the previous Labour government does not seem to be blamed much for the current fiasco, and the current fiasco has not become a major electoral issue yet.

And the list of screw-ups is substantial. G4S – the firm behind the Olympic security fiasco – has nowbeen selected to support the Police Service of Northern Ireland at the G8 Summit next month. Despite the company’s botched handling of the Olympics Games contract last summer, G4S has been chosen to supply 450 security staff for the event at Lough Erne, County Fermanagh The leaders of the world’s eight wealthiest countries are expected in Fermanagh on June 17 and 18. Meanwhile, medical assessments of benefit applicants at Atos Healthcare were designed to incorrectly assess claimants as being fit for work, according to an allegation of one of the company’s former senior doctors has claimed. Greg Wood, a GP who worked at the company as a senior adviser on mental health issues, said claimants were not assessed in an “even-handed way”, that evidence for claims was never put forward by the company for doctors to use, and that medical staff were told to change reports if they were too favourable to claimants. Elsewhere, Scotland’s hospitals were banned from contracting out cleaning and catering services to private firms as part of a new drive towards cutting the spread of deadly superbugs in the NHS. There were 6,430 cases of C. difficile infections in Scotland in one year recently, of which 597 proved fatal. The problem was highlighted by an outbreak of the infection earlier this year at the Vale of Leven hospital in Dunbartonshire which affected 55 people. The infection was identified as either the cause of, or a contributory factor in, the death of 18 patients.

Whatever our perception of the public perception, the impact on transparency and strong democracy merit consideration. As we outsource any public service, we appear to risk removing it from the checks and balances of good governance that we expect to have in place. Expensive corporate lawyers can easily outmanoeuvre under-resourced government departments, who often appear to be unaware of the consequences, and this of course is the nightmare scenario of the implementation of the section 75 NHS regulations. Even talking domestically, Where contracts privilege commercial sensitivities over public rights, they can be used to exclude the provision of open data or to exempt the outsourcer from freedom of information requests. Talking globally, “competing in the global race” has become the buzzword for allowing UK companies to outsource to countries that do not have laws (or do not enforce laws) for environmental protection, worker safety, and/or child labour. However, all of this is to be expected from a society that we are told wants ‘less for more’, but then again we never have this debate. Are the major political parties afraid to talk to us about outsourcing? Yes, and it could be related to that other ‘elephant in the room’, about whether people would be willing to pay their taxes for a well-run National Health Service, where you would not be worried about your local A&E closing in the name of QUIPP (see this blogpost by Dr Éoin Clarke). Either way, Jon Cruddas is right, I feel; the ‘modern anomie’ is the schism between the individual and the community, and maybe what Margaret Thatcher in fact meant was ‘There is no such thing as community’. If this means that Tony Blair feels that ‘it doesn’t matter who supplies your NHS services’, and we then get invasion of the corporates into the NHS, you can see where thinking like this ultimately ends up.

Putting the 'National' in 'National Citizen Service'

Every part of the country is up-for-grabs at the highest bidder. This is at the heart of the ‘Opening Public Services’ White paper. The problems concerning A4e are well-known, and the Government appears to little concerns about their widely-reported problems. Despite the national hysteria over the Gold medals in the Olympics, there has been disquiet about G4s and security.

Serco, a leading private contractor, is reported as being in line to win a multimillion-pound contract to run the National Citizen Service, proposed by the prime minister as a “big society”, non-military version of national service for youngsters aged over 16.

The company, which recently announced global revenue of more than £4646 million in 2011, has joined four charities in a controversial bid to run what has been described by the government as a key part of David Cameron’s big society vision. Serco and its partners hope to win eight of the 19 contracts currently up for tender, with an estimated value of nearly £100m over two years.

As a name, ‘National Citizen Service’, might sound like something which the State is running. For the Conservatives, the State is the overbloated, inefficient, authoritarian entity, whose size is worth dimininishing. For Labour, it affords a method of shared risk and responsibility, where infrastructure and investment can offer genuine security for all stakeholders. Differing ideological attitudes towards the State can to some extent been seen in the brand identity of the ‘National Health Service’.

If the ‘National Citizen Service’ were not a vehicle of the State, but a massive private entity, albeit in partnership with the third sector, where the private entity were to maximise shareholder dividend, would this be allowed? According to Companies House, which regulates the name of companies, the answer would be ‘yeah but…’ The current rules state that, to be called “National”, you need to demonstrate that the business is pre-eminent in its field by providing supporting evidence from an independent source such as a Government Department, trade association or other representative body. Here, there would be no problem as Cameron’s own Department would provide this evidence, presumably. It is noted in the rules that “pre-eminence is reduced if the overall name does not describe a product”, but you would still have to show that your business is substantial in its field of activity even if this was not described in the business name. It is not entirely clear what a ‘citizen service’ is, in the same way the ‘Work Programme’ is rather vague.

Martyn Hart, who is the Chairman of the UK’s National Outsourcing Association, recently described in the Guardian that: “Outsourcing is privatisation, they cry. Outsourcing is far from privatisation – done properly, the client remains in control at all times. The client’s purchasing a service, over a long period of time: as paying customer, they are perfectly entitled to specify exactly what they want. But a key facet of outsourcing is the shared bearing of risk: the partners are in it together. Not just financially, but also in terms of reputation. If things go wrong, both brands are weakened and, in the case of the supplier, future custom is jeopardised.”

Some would strongly disagree with this. Often the general public will not know the identities of the private companies to which functions have been outsourced, for example the cleaning in a state-run entity, so therefore will not know who to blame and how. Often lawyers have to ensure that there are clear clauses for the blame of third parties; such clauses are known as “third party liability” clauses, and often they turn into a legal mess when these private third parties themselves get taken over in a share acquisition. Who then is responsible? What happens if that third party goes out-of-business? Furthermore, awarding lots of outsourced contracts often leads to greater costs than if an organisation were simply able to organise the function itself. Therefore – in summary – business risks for outsourcing a large amount of work are therefore two-fold: control and cost.

The reality is that there is nothing national about these previously public services any more, other than a pre-eminence due to a rigged market only for winners. As a result of them being outsourced, foreign corporates can, and often, do control and own them, driven by their business model to make a profit. There is little accountability for them in reality, save for a small complaints department in a large multi-national company. And what happens if that company goes bust or makes a mess of the job? Well, you know the doctrine: you privatise the profit, but you let the State pick up the pieces for any disaster. That’s how ‘sharing of risk’ has always operated for the private sector in the public-private relationship.