At a time when “every penny counts”, it seems rather disgusting that thousands and millions of pounds should be diverted from frontline care (which we apparently can’t afford judging by the cuts in nursing jobs) to the commercial and corporate lawyers. Management consultants, politicians and staff in CCGs have no expertise in commercial law. Now that it turns out that commissioners could be freed to award work to a “prime contractor” over five to 10 years from 2014-15, according to the Department of Health, the issue of what happens if a subcontractor commits an offence in tort (negligence) or contract (breach of contract) is highly significant. The subcontractor’s damage could cause loss to the ultimate patient. Instead, commissioning pitches are full of inane garbage such as, “we need to do much better with much less“, when you consider that £20bn efficiency savings, aided and abetted by cuts in nursing staffing, is dwarfed by the new £80bn cost of #HS2. It is reported, for example, in the Health Services Journal, that,

At a time when “every penny counts”, it seems rather disgusting that thousands and millions of pounds should be diverted from frontline care (which we apparently can’t afford judging by the cuts in nursing jobs) to the commercial and corporate lawyers. Management consultants, politicians and staff in CCGs have no expertise in commercial law. Now that it turns out that commissioners could be freed to award work to a “prime contractor” over five to 10 years from 2014-15, according to the Department of Health, the issue of what happens if a subcontractor commits an offence in tort (negligence) or contract (breach of contract) is highly significant. The subcontractor’s damage could cause loss to the ultimate patient. Instead, commissioning pitches are full of inane garbage such as, “we need to do much better with much less“, when you consider that £20bn efficiency savings, aided and abetted by cuts in nursing staffing, is dwarfed by the new £80bn cost of #HS2. It is reported, for example, in the Health Services Journal, that,

“If the £120m deal is finalised, Circle ? which also runs Hinchingbrooke Health Care Trust ? will be financially and clinically accountable to commissioners for the whole pathway.”

but forgetting the spin (and one should really do that in the best interest of patients), this cannot be true if the subcontractors are excluded from liability under English law.

A useful starting point is the NHS Commissioning Board’s own “The NHS Standard Contract: a guide for clinical commissioners.”

This instrument defines the “prime contractor” as follows:

“Contract with prime contractor who is responsible for management and delivery of whole care pathway, with parts of care pathway subcontracted to other providers (Prime Contractor model). The prime contractor may not be the largest provider in the pathway but the role is focused on the pathway service delivery”.

However, the document perpetuates the notion of subcontractors’ accountability which the English Courts are likely to have difficulty with:

“The commissioner retains accountability for the services commissioned but is reliant on the prime contractor to hold subcontractors to account.”

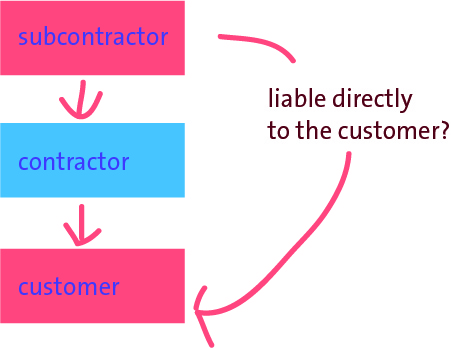

Understanding both the management principles about the safety culture in management and the legal implications of subcontracting converges on one particular industry: the construction industry. A main contractor may engage another person in order for that subcontractor to undertake a specific part of the main contractor’s works. Subcontracting is favoured in the house building industry because it offers main contractors flexibility and cost efficiencies (Ireland, 1988). However, parallels are confounded by the fact that commissioning NHS services is not the same as making buildings, the lessons from different jurisdictions are different, the degree of ‘commerciality’ of the actual contract (e.g. residential building can even be different from corporate building), the actual material facts of how close the parties are legally vary, subtle differences in the nature of contractual terms, the finding that the nature of loss may not be the same, and so it goes on. It is increasingly clear from any rudimentary analysis that the subcontractor cannot be easily accountable to the patient at all, because of a number of well settled legal principles.

A study of safety culture among subcontractors in the domestic housing construction industry using in depth semi structured interviews with 11 subcontractors from six different trades by Phil Wadick from Bellingen, Australia found that subcontractors place an enormous amount of trust in their own common sense to help inform their safety judgements and decisions (Wadick et al., 2010). According to their study, subcontractors have a deep respect and trust for the safety knowledge gained from years of practice, and a distrust of safety courses that attempt to privilege paper/procedural knowledge over practical, embedded and embodied safety knowledge.

In the law of tort, a party does not need to have a contract with another to be liable directly to that party in negligence. The legal principle of privity of contract, as stated below from Treitel, does not preclude third parties from suing contracting parties in tort.

“The doctrine of privity of contract means that a contract, as a general rule, confer rights or impose impositions arising under it on any person except the parties to it.” (GH Treitel, “The Law of Contract”)

This privity of contract is the root cause of the personal tragedy depicted in this video from the US jurisdiction, of Wendell Potter and Nataline Sarkisian: there is no direct contract between insurer and insuree.

You can see the smoking gun all too easy for this jurisdiction, where the CCGs are state insurance schemes. In England, there’s no contract between patient and provider, but only between provider and CCG and (implicitly) between CCG and NHS England. As stated correctly by Nicholas Gould, a Partner in Fenwick Ellott (the largest construction and energy law firm in the UK), there is no direct contractual link between the employer and the subcontractor by virtue of the main contract for the construction scenario. In other words, the main contractor is not the agent of the employer and conversely the employer’s rights and obligations are in respect of the main contractor only. The employer therefore cannot sue the subcontractor in the event that the subcontractor’s work is defective, is lacking in quality, or delays the works. The subcontractor situation therefore merits some particular scrutiny in the law of tort, where it is necessary to establish a breach of a duty of care, with sufficient cauality, to prove negligence on the balance of probabilities.

Typically, in their contracts, the “prime contractor” will limit its liability to a customer to a patient ultimately, and in turn the subcontractor will limit its liability to the prime contractor. In the 2004 case of Rolls-Royce New Zealand Ltd v Carter Holt Harvey Ltd [2004] NZCA 97; [2005] 1 NZLR 324 (23 June 2004) “Rolls Royce”, the Court of Appeal of New Zealand decided that the subcontractor in that construction case could not be liable to the customer. In Rolls Royce, the Court of Appeal said that whether or not a duty of care should be recognised in New Zealand depended on whether, in all the circumstances, it was just and reasonable that such a duty is imposed. This, in turn, involves two broad fields of inquiry. First is the degree of proximity or relationship between the parties, and second is whether there are any wider policy considerations that might negate or restrict or strengthen the existence of a duty in any particular class of case.

But can a duty-of-care by the subcontractor be held in tort in the English law? The House of Lords attempted to establish a general duty of care in respect of pure economic loss resulting from a negligent act, based on the closeness of the relationship between the parties and reliance by the claimants on the defendants’ skill and experience, in Junior Books Ltd v Veitchi Co Ltd [1982] UKHL 4 (15 July 1982). This Scottish case represents the high water mark for liability in tort for subcontractors to employers in respect of negligence. In this case a contractor was engaged to construct a factory for the building owner. The defendant subcontractors were engaged to lay a specialist composite floor. The floor was defective and began to crack almost immediately. However, there was no danger to the health and safety of the occupants, nor any danger to other property of the building owner. Regardless, the floor needed replacement because of the defects. There was no direct contract between the employer and the subcontractor, but the building owner sought the costs of replacement and loss of profit while the flooring was being relayed from the subcontractor, and succeeded in the House of Lords. Lord Keith of Kinkel advised about the need to avoid extrapolating too widely from the ratio of this case:

But can a duty-of-care by the subcontractor be held in tort in the English law? The House of Lords attempted to establish a general duty of care in respect of pure economic loss resulting from a negligent act, based on the closeness of the relationship between the parties and reliance by the claimants on the defendants’ skill and experience, in Junior Books Ltd v Veitchi Co Ltd [1982] UKHL 4 (15 July 1982). This Scottish case represents the high water mark for liability in tort for subcontractors to employers in respect of negligence. In this case a contractor was engaged to construct a factory for the building owner. The defendant subcontractors were engaged to lay a specialist composite floor. The floor was defective and began to crack almost immediately. However, there was no danger to the health and safety of the occupants, nor any danger to other property of the building owner. Regardless, the floor needed replacement because of the defects. There was no direct contract between the employer and the subcontractor, but the building owner sought the costs of replacement and loss of profit while the flooring was being relayed from the subcontractor, and succeeded in the House of Lords. Lord Keith of Kinkel advised about the need to avoid extrapolating too widely from the ratio of this case:

“Having thus reached a conclusion in favour of the respondents upon the somewhat narrow ground which I have indicated. I do not consider this to be an appropriate case for seeking to advance the frontiers of the law of negligence upon the lines favoured by certain of your Lordships. There are a number of reasons why such an extension would, in my view, be wrong in principle.”

The courts began, however, to retreat from the implications of Junior Books almost immediately. The leading speech was given by Lord Roskill and he based his analysis on Lord Wilberforce’s infamous two stage test for establishing a duty of care set out in Anns v Merton London Borough Council [1977] UKHL 4 (12 May). This approach was of course overruled in Murphy v Brentwood District Council [1990] UKHL 2 (26 July). In Southern Water Authority v Carey [1985] 2 All ER 1077, the work was defective and the entire sewerage scheme failed. The Authority sued the subcontractor in negligence, and yet the High Court decided that the subcontractor was not liable in tort as a result of the terms of the main contract.

Nonetheless, there are a variety of general principles applicable to subcontractor relationships. First, the main contractor remains responsible to the employer for a number of diverse aspects of the subcontract. In other words, the main contractor is still responsible for time, quality and paying the subcontractor in accordance with the contract between the main contractor and subcontractor regardless of any issue that could arise between the main contractor and the employer. This will of course depend upon the terms of the contract between the main contractor and a subcontractor, and might also depend on the separate contract between the employer and main-contractor. However, they are nonetheless two separate contracts, and the legal doctrine of privity of contract applies in this jurisdiction as in many jurisdictions for the “prime contractor model”, and the matching or integration of similar “back to back” obligations is often unsatisfactory. Clever drafting can even lead to the subcontractors escaping liability altogether. For example, quite recently, it is reported that a dredging subcontractor, Van Oord, escaped liability for the design of dredging works due to the exclusion clause in its tender (Mouchel Ltd. v Van Oord (UK) Ltd., [2011] EWHC 72).

With all this uncertainty, it is quite unhelpful that there is also much uncertainty about how a subcontractor will have been deemed to have ‘failed': the so-called “outcomes-based commissioning“. It could be that there could also be patient feedback indicators built into the deal, which commissioners hope will enable them to hold the lead provider to account if people’s experience of services suffers. “Soft intelligence” from GPs could also be used. The legal cases will certainly turn on their own material facts, but, with a time window which could be as large as 10-15 years and with fairly strong private providers financially (important for business continuity), it is likely that the English law courts will be asked at some stage to decide upon whether the subcontractor can be legally ‘accountable’ to the patient. The answer is very likely to be “no”, and there will be then many very angry intelligent people who will feel that they simply have been misled. A lot of liability rests with the CCG accountable officer position – but if all goes wrong such officers can simply move onto other well-paid jobs in other sectors. When you consider the death of legal aid for clinical negligence, some might say this a real mess.

Not to worry – it’s business as usual.

Further reading

Ireland, V. (1988), Improving Work Practices in the Australian Building Industry. A Comparison with the UK and USA, Master Builders Federation of Australia.

Wadick, P (2010), Safety culture among subcontractors in the domestic housing construction industry, Structural SurveyVol. 28 No. 2, pp. 108-120

Pingback: Will looking for blame in the 'prime contractor model' end up like one giant "pass-the-parcel"? - Socialist Health Association()

Pingback: Matthew d’Ancona on the formation of the Coalition: they were the future once()

Pingback: Many people were warning about competition in the NHS long before Polly Toynbee. Me for example.()

Pingback: The ‘NHS Five Year Forward Plan’ is a clever marketing stunt, and is barely a statement of strategy()

Pingback: Prime Contractor Nhs | job get contractor quotes()