Home » Posts tagged 'Living well with dementia' (Page 4)

Tag Archives: Living well with dementia

Is prevention of dementia merely a pipe dream?

Predicting the future on the basis of your past is of course the ultimate goal of the shopping industry.

It also seems to be the goal of healthcare, as consumer behaviour and patient care appear to converge in ever-marketised healthcare.

When you ‘sign up’ for a health subscription somewhere, one day, it’s possible you’ll be offered “packages” most suitable for you. Consider them like targetted adverts on Facebook. Of course, with disease registries compiled on your behalf by public health through data sharing, tomorrow’s world is getting ever closer.

So how much of dementia is in your ‘control’, if you haven’t yet developed it?

Is prevention of dementia a pipe dream? There are, after all, many factors which we’re born with which can have a huge influence. These are known as generic factors.

Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, is already testing unmanned drones to deliver goods to customers. The drones, called Octocopters, could deliver packages weighing up to 2.3kg to customers within 30 minutes of them placing the order. Amazon has filed a patent that will allow it to ship a package to you before you even know you’ve bought it.

To give you another example, I know someone who was being given sponsored ads for hotels in Bilboa after Facebook had picked up her location by GPS.

Now back to the past.

Back to Black in fact.

The Black report was a 1980 document published by the Department of Health and Social Security (now the Department of Health) in the United Kingdom, which was the report of the expert committee into health inequality chaired by Sir Douglas Black. It was demonstrated that although overall health had improved since the introduction of the welfare state, there were widespread health inequalities.

Full Text of the Black Report, supplied by the Socialist Health Association website.

Surprisingly enough, it’s not all doom and gloom.

Modulating the environment might have some sort of impact on prevention of dementia, even if we don’t yet know how big or small this impact is.

The study of exceptionally long-living individuals can inform us about the determinants of successful aging. There have been few population-based studies of centenarians and near-centenarians internationally. But a recent study involving individuals 95 years and older were recruited from seven electoral districts in Sydney provided evidence that dementia is not “inevitable” at this age and independent living is common.

Low socioeconomic status in early life is well known to affect growth and development, including that of the brain; and it has also been shown to affect the risks of other chronic diseases.

Over a decade ago, a real attempt was made to relate early socioeconomic status to later dementia. We found results consistent with the hypothesis that a healthier socioeconomic environment in childhood and adolescence leads to more “brain reserve” (the brain’s ability to cope with increasing age- and disease-related changes while still functioning) and less risk of late-life dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, later on.

Results from two major cohort studies, led by the University of Cambridge and supported by the Medical Research Council, have reveal that the number of people with dementia in the UK is substantially lower than expected because overall prevalence in the 65 and over age group has dropped.

Three geographical areas in Newcastle, Nottingham and Cambridgeshire from the initial MRC Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (CFAS) examined levels of dementia in the population. The latest figures from the follow up study, CFAS II, show that there is variation in the proportion of people with dementia across differing areas of deprivation, suggesting that health inequalities during life may influence a person’s likelihood of developing dementia.

The prevalence of dementia in the general population might be subject to change.

Factors that might increase prevalence include: rising prevalence of risk factors, such as physical inactivity, obesity, and diabetes; increasing numbers of individuals living beyond 80 years with a shift in distribution of age at death; persistent inequalities in health across the lifecourse; and increased survival after stroke and with heart disease.

By contrast, factors that might decrease prevalence include successful primary prevention of heart disease, accounting for half the substantial decrease in vascular mortality, and increased early life education, which is associated with reduced risk of dementia.

The study was led by Professor Carol Brayne from the Cambridge Institute of Public Health at Cambridge University. She opined that whether or not these gains for the current older population will be borne out in later generations might depend on whether further improvements in primary prevention and effective health care for conditions which increase dementia risk can be achieved, including addressing inequalities.

In fact, it has been recently appreciated that cardio-metabolic risk factors have been associated with poor physical and mental health.

An association of low education with an increased risk of dementia including Alzheimer’s Disease, the most common cause of dementia globally, has been reported in numerous cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Education and socioeconomic status are highly correlated, it turns out.

The reserve hypothesis has been proposed to interpret this association such that education could enhance neural and cognitive reserve that may provide compensatory mechanisms to cope with degenerative pathological changes in the brain, and therefore delay onset of the dementia syndrome.

The complexity of people’s occupations also positively influences cognitive vitality, and this relationship becomes increasingly marked with age.

Further evidence from studies suggests that a poor social network or social disengagement is associated with cognitive decline and dementia.

The risk for dementia including Alzheimer’s Disease was also increased in older people with increasing social isolation and less frequent and unsatisfactory contacts with relatives and friends. Rich social networks and high social engagement imply better social support, leading to better access to resources and material goods.

Previous studies have also shown that social determinants not directly involved in the disease process may be implicated in the timing of dementia diagnosis. Possibly the living situation is related to the severity of dementia at diagnosis. If so, primary care providers should have a low threshold for case-finding in older adults who live with family or friends?

Regular physical exercise was reported to be associated with a delay in onset of dementia including Alzheimer’s Disease among cognitively healthy elderly.

In the Kungsholmen Project, the component of physical activity presenting in various leisure activities, rather than sports and any specific physical exercise, was related to a decreased dementia risk. It is generally thought that physical activity is important not only in promoting general and vascular health, but also in promoting some form of brain rewiring.

Various types of mentally demanding activities have been examined in relation to dementia in general, including knitting, gardening, dancing, playing board games and musical instruments, reading, social and cultural activities, and watching specific television programs, which often showed a protective effect.

So it really might not all the doom and gloom, and certainly we are much further forward than we were 33 years ago with the publication of “The Black Report”.

For the record, this Report doesn’t even mention dementia.

Prof Alistair Burns in New Scientist writing “Dementia: A silver lining but no room for complacency” summarised elegantly the situation as follows, on 10 January 2014:

“While it is true that there is no cure, the findings suggest that prevention is at least possible. This must surely explain any reduction in prevalence, so what might be behind it? Improved cardiovascular health, better diet and higher educational achievement are all plausible explanations. This opens up the possibility that people who are able to take control of their lives can reduce their individual risk of dementia.”

So, to answer the actual question.

There is a realistic possibility that we might be able to identify certain people who are most at risk of developing a dementia, and modifying the known risk factors constitutes ‘low hanging fruit’ for policy. If you park aside the corporate capture potential of making new markets through development of health promotion packages, this is indeed an example, shock horror, of where data sharing across the whole population might be helpful and direct the health of the nation in future.

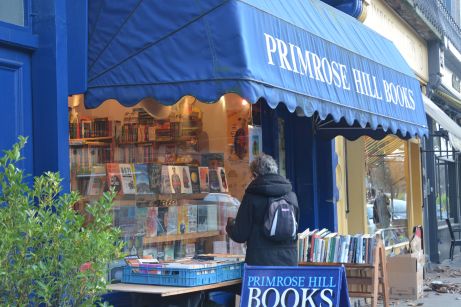

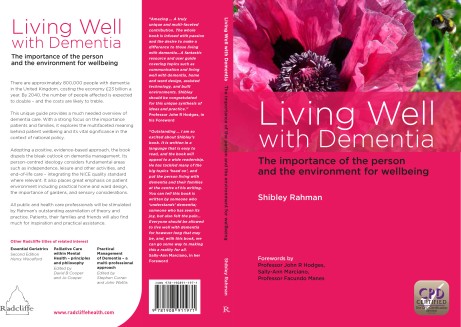

I bought today my own book “Living well with dementia” at a bargain price from Primrose Hill Books

I got a bargain today.

I have been quite a good mood recently, getting ready for my book launch in Camden on the afternoon of February 15th, 2014. We’re all going out for dinner in Pizza Xpress later that evening, somewhere in Central London.

I bought my own book ‘Living well with dementia’ from Primrose Hill Books for the very much discounted price of £16.99.

This is not because it was a soiled copy, or because I was the buyer.

It was because they had ordered it in especially from the wholesalers, and managed to sell it onto me a very much reduced price.

Of course I am very grateful, as I think it’s important to support local independent booksellers in the community.

Here’s a good piece from last year on ‘five reasons to support your local indie bookseller‘.

Here are the full details of ‘Primrose Hill Books’. They’re on the main road which passes through Primrose Hill. This book is called Regents Park Road.

Nonetheless, I appreciate that some people will prefer to use the bigger well known book retailers, especially if they do not time to browse or travel to such bookstores.

After a bit of haggling, we got Amazon this afternoon to reduce their delivery time from 9-11 days to fewer than 24 hours. This is of course a huge result for me. Their page on my book is here.

The Blackwells Bookstore is normally a good place to find the book for immediate delivery, but not at the time of writing this blogpost. The book is currently out of stock, but I do know reliably they had a good stock once upon a time. Here is their page.

But Primrose Hill Books will always have a special place in my heart. I’ve bought books there I’d never have ordered on Amazon, for example, through browsing.

It’s run by Jessica and Marek (and Kelly is often there too). All three have an enclopaedic knowledge of current books, some well known, some not so well known.

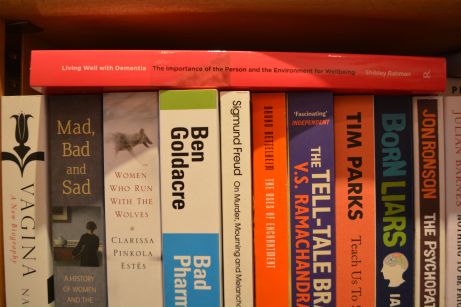

Of course, it was a source of great pride to see my book there. I’ve published specialist textbooks, but not the type which would look in place in the bookshop above or any other high street bookseller.

Here’s Jess looking at the book.

She said it was a good book, and we had a discussion of how long it had taken me to write (a year), how this had become a real passion of mine to share this information and to dispel all the scientific misinformation about dementia, and how it was written in the style of a long blogpost but it actually contained a lot of interesting contemporaneous evidence and discussion.

It is of course a bit weird to see the book alongside classics such as Ben Goldacre’s “Bad Pharma: How medicine is broken, and how we can fix it” and Naomi Wolf’s “Vagina”. But hey ho.

You can buy the book from the publishers’ website too.

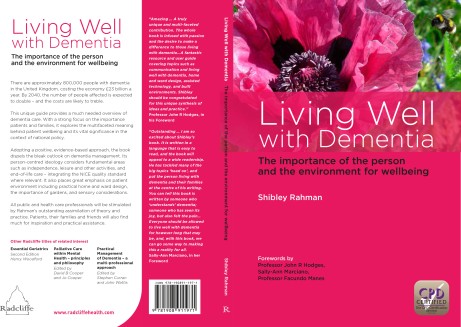

Their is their official flier. You get 20% off if you use the promotional code ‘AUTHOR20′. You enter this code apparently just when you are completing the ‘checkout’ in this e-bookstore.

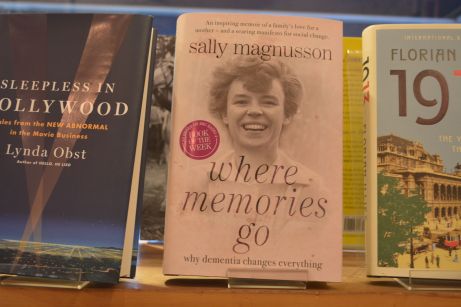

And finally, one of the people I genuinely admire the most is Tommy Whitelaw (please support Tommy at “@tommyNTour“).

You can read about Tommy’s campaign for giving carers ‘a voice’ on my blog here. His story continues to motivate me very much – and not just because he’s a Glaswegian like me!

Tommy is very honoured that his campaign and letters in Sally Magnusson’s Book “Where Memories go”.

Hopefully the episode where Sally talks to Tommy in “Medical matters: caring for carers” will be made available on the BBC iplayer shortly.

And finally – here’s Sally’s book on the Hodder website.

All in it together, and all that.

Twitter’s telling me some of you have received my book at last!

Thanks to Rhona Light (“@Hippiepig“) for giving me feedback on my book. She was the very first to receive it.

Rhona’s copy of her book arrived yesterday.

@legalaware Sorry I can’t tweet a pic as it says over memory limit but it is super. Poppy cover with CPD cert logo and forewords attrib.

— Rhona Light (@Hippiepig) January 28, 2014

@legalaware Good quality paper and very clear print. You will be pleased.

— Rhona Light (@Hippiepig) January 28, 2014

@legalaware Proper medical textbook quality x

— Rhona Light (@Hippiepig) January 28, 2014

@legalaware it is very well structured. I think that it is very well sub-headed. It is highly accessible for a non-medical person like me.

— Rhona Light (@Hippiepig) January 28, 2014

@legalaware It is very readable – your style is great and it is wonderful to read a book that is so well researched and balanced. This will

— Rhona Light (@Hippiepig) January 28, 2014

@legalaware be the standard textbook for courses. Just stunning.

— Rhona Light (@Hippiepig) January 28, 2014

Thanks also to @KateSwaffer for her supportive comments about my book.

@Hippiepig @legalaware I agree even though I’m only half way through this wonderful book

— Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer) January 28, 2014

And Rose got it too (@RoseHarwood1):

@legalaware @dementia_2014 @nursemaiden @WhoseShoes @charbhardy It’s arrived! Can’t wait to get stuck in!  x pic.twitter.com/RccxttOCQF

x pic.twitter.com/RccxttOCQF

— Rose Harwood (@RoseHarwood1) January 29, 2014

If you buy the book off Amazon, please remember not to buy it directly from them or you could be waiting 9-11 days. Here’s the link to the book on Amazon. I bought it today from “The Book Depository” as my complimentary copies hadn’t arrived. But I know it’s selling well. Yesterday it reached #3 in the UK.  And I was honoured to receive this tweet from Prof Simon Wessely, who is at the Maudsley/Institute of Psychiatry, and President-Elect of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

And I was honoured to receive this tweet from Prof Simon Wessely, who is at the Maudsley/Institute of Psychiatry, and President-Elect of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

@legalaware am impressed..looking forward to it hitting number 1 — Simon Wessely (@WesselyS) January 27, 2014

I’ll be presenting the book to 25 guests in private in Camden on Saturday 15th February 2014. This includes of course Charmaine Hardy whose poppy is on the front cover:

@piponthecommons @legalaware thanks it’s Shibley written it

— Charmaine Hardy (@charbhardy) January 29, 2014

@kgimson @ILoveLincs @legalaware thank you I’m so proud x

— Charmaine Hardy (@charbhardy) January 29, 2014

This is the book @legalaware has written with my photo on the front cover. I’m so proud pic.twitter.com/4koQ12nnq5

— Charmaine Hardy (@charbhardy) January 29, 2014

Thanks a lot to Pippa Kelly too (@piponthecommons)

@charbhardy @legalaware Congratulations to you both! Great achievement. Wonderful cause.

— Pippa Kelly (@piponthecommons) January 29, 2014

And I look forward to going out for dinner with them in the evening in Holborn.

Thanks

I’ve been finalising copyright permissions for my book this week.

It’s been a lot of work, but it’s very important.

In general, I have acknowledged people in the main text, and cited the sources of extracts clearly wherever possible. I should particularly like to thank the following for being very kind in providing for me relevant copyright permissions: Beth Britton (specialist blogger on dementia issues), BMJ Publishing Group Limited (for extracts from original articles in the ‘British Medical Journal’ and ‘Journal of Medical Ethics’), Department of Health (for extracts under open license of crown copyright publications from their Government department and for extracts from the ‘NHS Choices’ website), Dr Martin Brunet (rapid response to a BMJ article), Gill Phillips (for ‘Whose Shoes’ material, on behalf of Nutshell Communications Limited), Guardian and Observer newspaper (for short extracts), Hawker Publications Limited (for an extract from ‘Journal of Dementia Care’), Local Government Association, National Council for Palliative Care, Nuffield Council on Bioethics, Sue Learner, and the World Health Organization (and Alzheimer’s Disease International, for extracts from “Dementia: a public health priority”).

I am also especially grateful to Simona Florio and her management team, and individuals pictured themselves, at the “Healthy Living Club” (in Stockwell, London) for kind permission of photographs provided in figures 7.1 and 10.1 of this book.

I have now signed off the final proofs

I have now ‘signed off’ the final proofs. The next thing is to organise a book launch evening for friends who’ve been following the progress of the book. Please let me know if you wish to be invited at livingwelldementia@gmail.com, though it’s fairly certain I will be inviting you anyway if I’ve been in regular contact on my Twitter accounts @legalaware or @dementia_2014.

I am taking my 11000 Twitter followers all the way in promoting wellbeing in dementia

I am taking my 11000 followers on Twitter (@legalaware) all the way in engagement over the G8 ‘dementia summit’.

Anna Hepburn at the Department of Health will be spearheading implementation of its own digital strategy on 11 December 2013, which I am looking forward to enormously (here).

A friend of mine is a prominent campaigner for dementia. He lives with a type of dementia which is quite common in a certain age group.

I was aghast when he said this week he had attended a clinical commissioning group meeting, but had faced stigmatising language about dementia. The leader of that meeting had referred to someone having ‘a bit of dementia’. My friend was not impressed, but politely wrote to him afterwards. The leader replied with dignity.

But this for me epitomises the uphill battle those of us who genuinely care about dementia really face.

My baptism of fire into the world of dementia is when I did cognitive assessments in Cambridge of patients with frontal dementia, for Professor John Hodges who was chair of behavioural neurology at the time.

Since then, and bear in mind that this is more than ten years ago, I have firmly believed that there is no more important voice than the person with dementia.

Also, it has become apparent to me that there are many in the caring professions, including of course carers who confront challenges to their own health. It seems that they also are expected to tiptoe with effortless ease through the maze of the law and finance, as well as information about the condition itself.

Sure, the drive for a ‘cure’ and ‘better treatments’ for dementia as a ‘key priority’ from the Alzheimer’s Society (their press release on the ‘G8 summit’) is a worthy and commendable one. However, individuals with dementia and the people who are close to them need to have realistic expectations about what the drugs can do – and what they can’t do.

There are invariably going to be pressures on English policy in dementia policy, and dementia itself has to compete with a finite pot of resources compared to other very important long term conditions (such as chronic obstructive airways disease).

In the absence of a magic cure for the more prevalent types of dementia, such as dementia of Alzheimer type, I believe a huge amount of effort morally must be put into improving the quality of life of those loved ones with dementia.

I particularly admire Beth Britton for her work in dementia. Beth on her blog produces a clear first-hand precious witness of her father, whose journey of vascular dementia was for around 19 years. I had the good fortune to meet Beth, Gill Phillips (the force behind the ‘Whose Shoes‘ tool) and Kate Swaffer recently when Kate was visiting from Oz. Kate’s blog on personal experiences of living with dementia is a candid tour de force. Both Beth and Kate have reasonable expectations from society of its reaction to people living with dementia. Their voices have to be heard clearly through the noise of the system.

These are examples of genuine people, who care. Their passion for explaining the importance of the person is authentic. It’s real.

I am nearly 40, and I realised a few years ago that anything can happen to anybody at any time. This crisis of insight occurred precisely at the moment when I woke up from a six week coma in a London NHS Trust, as I had contracted meningitis. It’s how I became physically disabled.

When I studied medicine for all of six years at Cambridge, and did my postgraduate studies in London, I had never heard of Tom Kitwood. Kitwood was, however, remarkable for revolutionising the way we think about dementia.

@PeterDLROW @legalaware @val_hudson @alzheimerssoc @bethyb1886 Kitwood is at the foundation of all thats right about #dementia care

— Lucy Jane marsters (@lucyjmarsters) November 23, 2013

Medics are transfixed on their medical model, but Kitwood put the person in pole position in dementia care. This is extremely potent, corroborated in subsequent policy from SCIE on personalisation and person-centred care. I have indeed devoted a whole chapter to it in my book ‘Living well with dementia’.

Policy makers owe a debt they can never actually repay from people with dementia (such as Norman McNamara) or people who have come up close with dementia (such as Tommy Whitelaw and his late Mum Joan, whom Tom clearly adored).

In a closely-knit group of #dementiachallengers, @charbhardy is also “first amongst equals”! As Charmaine’s Twitter profile says, she is a carer to her husband with ‘PPA’.

PPA is primary progressive aphasia, a rare type of dementia. All the dementias have specific needs.

Charmaine’s poppy is even on the front cover of my book, with kind permission of course! You will see some striking pictures of sterling gardening when you visit her Twitter profile. The flowers at the top of this blogpost are hers.

My book completely rubbishes the view that nothing can be done to help individuals with dementia. Quite the reverse.

A lot CAN be done; whether this is improving the design of the personal home, care home, or ward; improving the outside environments such as paving; improving adaptations and technologies for the home; improving advocacy for people with dementia and their carers; improving networks and social inclusivity (through even the social media); promoting dementia friends and dementia-friendly communities (even banks); encouraging debate (e.g. through Mr Darren Gormley’s excellent blog.)

Or it might include improving information for persons with dementia or their carers. See for example Lee’s “Dementia Challengers” resource which shows ‘choice’ to be more than some minor policy whim; it’s a real thing which can help people to live successfully with dementia.

There is therefore a huge deal which could and should be done.

However, the system is like a giant oil-tanker where it’s really hard to change direction. Beth Britton’s blog is amazing – I can’t praise it highly enough. This, however, upset me about how Beth’s own father had been treated (from a blogpost of Beth from 6 November 2013, entitled “Does the world really stop?”):

I lost count of the young doctors who saw my dad during his 19 years with dementia and questioned the point of treating a man who a) had a terminal disease, b) was immobile (as dad was for many years), c) doubly incontinent, d) had a swallowing problem (for the last four years of his life) and e) apparently in their narrow-minded judgement, had no quality of life whatsoever.

And this was Sally‘s experience (from the Foreword from my book):

Dementia of Alzheimer type destroyed his brain so badly that my father was unable to feed himself, mobilise, or verbalise his needs. He became totally dependent on my mother 24/7. As the condition advanced, my father became increasingly frail, with recurrent chest infections due to aspiration from swallowing difficulties. Each time the GP would be called out, antibiotics prescribed, and so the cycle would begin again. As a nurse, I wanted to see proactive management of my father’s condition. The system locally, however, was quite unable to provide this service. I feel that the dementia of Alzheimer type is a terminal condition, and, as such, should be treated like other similar conditions in care models. What we instead experienced was a “reactive “system of care where the default option was admission to hospital into an environment where my father would quickly decline.

I am lucky as I work closely with international people of the highest calibre around the world; we have a real focus on trying to witness the quality of life resulting from policy, researching it, and doing something about any shortfalls.

Through my 11000 followers, I am hoping to take some people, from all parts of society, on this journey with me. ‘Dementia is everybody’s business’, as this excellent badge from Lucy Jane Marsters shows.

I hope very much you’ll be inspired by Beth, Gill, Kate, Lee, Lucy Jane, Norman, Sally, and Tommy and others to make dementia your concern too. It’s the type of society we all have a stake in and we should not be afraid to learn from brilliant members of society who happen to live with dementia.

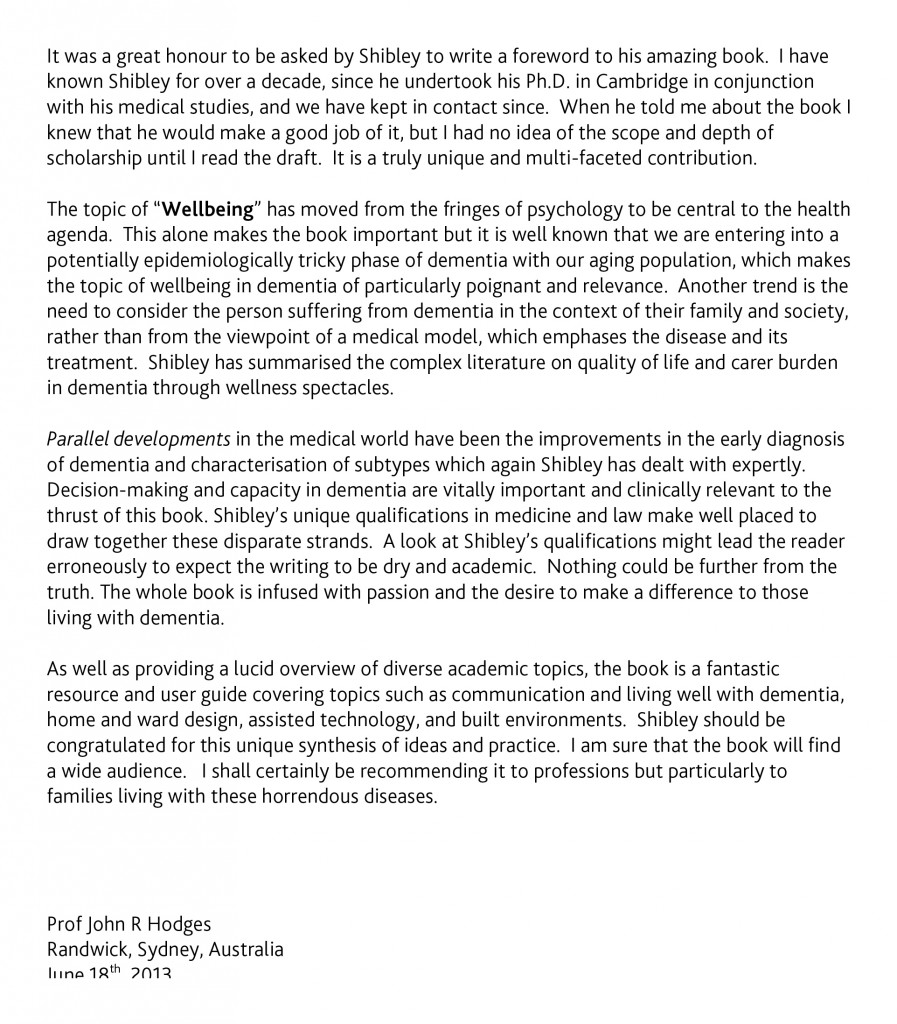

Foreword to my book 'Living well with dementia' by Prof John Hodges

This is the Foreword to my book entitled ‘Living well with dementia‘, a 18-chapter book looking at the concept of living well in dementia, and practical ways in which it might be achieved. Whilst the book is written by me (Shibley), I am honoured that the Foreword is written by Prof John Hodges.

Prof Hodges’ biography is as follows:

John Hodges trained in medicine and psychiatry in London, Southampton and Oxford before gravitating to neurology and becoming enamoured by neuropsychology. In 1990, he was appointed a University Lecturer in Cambridge and in 1997 became MRC Professor of Behaviour Neurology. A sabbatical in Sydney in 2002 with Glenda Halliday rekindled a love of sea, sun and surf which culminated in a move here in 2007. He has written over 400 papers on aspects of neuropsychology (especially memory and languages) and dementia, plus six books. He is building a multidisciplinary research group focusing on aspects of frontotemporal dementia.

Many posts like this have originally appeared on the blog of the ‘Socialist Health Association’. For a biography of the author (Shibley), please go here.

Many posts like this have originally appeared on the blog of the ‘Socialist Health Association’. For a biography of the author (Shibley), please go here.

Shibley’s CV is here.

Foreword to my book ‘Living well with dementia’ by Prof Facundo Manes

This is a Foreword to my book entitled ‘Living well with dementia‘, a 18-chapter book looking at the concept of living well in dementia, and practical ways in which it might be achieved. Whilst the book is written by me (Shibley), I am honoured that this particular Foreword is written by Prof Facundo Manes.

There are two other Forewords that also make for a brilliant introduction to my book.

Sally-Ann Marciano’s Foreword is here.

Prof John Hodges’ Foreword is here.

Prof Manes’ biography is here (translation by Google Translate):

“Facundo Manes is an Argentinian neuroscientist. He was born in 1969, and spent his childhood and adolescence in Salto, Buenos Aires Province. He studied at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Buenos Aires, where he graduated in 1992, and then at the University of Cambridge, England (Master in Sciences). After completing his postgraduate training abroad (USA and England) he returned to the country with the firm commitment to develop local resources to improve clinical standards and research in cognitive neuroscience and neuropsychiatry.

He created and currently directs INECO (Institute of Cognitive Neurology) and the Institute of Neurosciences, Favaloro Foundation in Buenos Aires City. Both institutions are world leaders in original scientific publications in cognitive neuroscience. He is also President of the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Aphasia and Cognitive Disorders (RGACD) and of the Latin American Division of the Society for Social Neuroscience. Facundo Manes has taught at the University of Buenos Aires and the Universidad Católica Argentina. He is currently Professor of Neurology and Cognitive Neuroscience, Faculty of Medicine and Psychology of the Favaloro University and was appointed Professor of Experimental Psychology at the University of South Carolina, USA.

He has published over 100 scientific papers in the most prestigious original specialised international journals such as Brain and Nature Neuroscience. He has also given lectures at several international scientific fora as the “Royal Society of Medicine” (London) and the “New York Academy of Sciences”, among others. His current area of ??research is the neurobiology of mental processes. He believes in the importance of scientific disclosure for Society. He led the program ” The Brain Enigmas ” on Argentina TV and wrote many scientific articles in the national press. Finally, Prof. Facundo Manes is convinced that the wealth of a country is measured by the value of human capital , education, science and technology, and that there is the basis for social development.

This biography wants to put on record this journey. And the beginning of the future.”

FOREWORD TO ‘LIVING WELL WITH DEMENTIA’ BY PROFESSOR FACUNDO MANES, PROFESSOR OF NEUROLOGY AND COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE AT FAVAROLO UNIVERSITY, BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA AND CO-CHAIR OF THE WORLD FEDERATION OF NEUROLOGY APHASIA/COGNITIVE DISORDERS RESEARCH GROUP

A timely diagnosis of dementia can be a gateway to appropriate care for that particular person. Whilst historically an emphasis has been given to medication, there is no doubt that understanding the person and his or her environment is central to dementia care. Shibley’s book will be of massive help to dementia researchers worldwide in my view, as well as to actual patients and their carers, and is great example of the practical application of research. For patients with dementia, the assistance of caregivers can be necessary for many activities of daily living, such as medication management, financial matters, dressing, planning, and communication with family and friends. The majority of caregivers provide high levels of care, yet at the same time they are burdened by the loss of their loved ones. Interventions developed to offer support for caregivers to dementia patients living at home include counselling, training and education programmes, homecare/health care teams, respite care, and information technology based support. There is evidence to support the view that caregivers of patients with dementia especially benefit from these initiatives.

I am currently the Co-Chair of Aphasia/Cognitive Disorders Research Group of the World Federation of Neurology (WFN RG ACD). In this group, we also have a specialist interest in world dementia research. “Wellbeing” is notoriously difficult to define. Indeed, the World Health Organization indirectly defines wellbeing through its definition of mental health:

“Mental health is defined as a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.” (WHO, 2011)

Such a definition necessarily emphasises the potential contribution of a person to society. Some people who participate in research are voluntarily contributing to society. Irrespective of the importance that they assign to their own wellbeing, it is the duty and responsibility of researchers to protect participants’ wellbeing and even to contribute towards it if possible. Participating in research can and should be a positive experience.

I felt that there is much ‘positive energy’ in dementia research around the world. Dementia research is very much a global effort, and many laboratories work in partnership both nationally and internationally, where expertise can be pooled and more progress can be made through collaborative efforts.

In England, the support and funding of world-class health research in the best possible facilities by NIHR, Medical Research Council, the Economic and Social Research Council and the Research Charities is vital to the development of new and better treatments, diagnostics and care. Likewise, the “World Brain Alliance” is working toward making the brain, its health, and its disorders the subject of a future United Nations General Assembly meeting. As part of this effort, a “World Brain Summit” is being planned for 2014, Europe’s “Brain Year,” to create a platform involving professional organisations, industry, patient groups, and the public in an effort to set a World Brain Agenda.

It is certainly appropriate to think these are exciting times, at last, for living well with dementia.

Prof Facundo Manes

Buenos Aires,?Argentina

24th August 2013

References

Mental health: a state of wellbeing. [October 2011]

A Foreword to my book ‘Living well with dementia’ written by Sally-Ann Marciano (@nursemaiden)

This book has now been published and is available here.

I am very grateful to Sally-Ann for writing a Foreword to my book on ‘Living well with dementia’. The other Foreword has been written by Prof John Hodges, Professor of Cognitive Neurology, NEURA Australia and Emeritus Professor of Behavioural Neurology Cambridge University. Sally-Ann offers an unique perspective regarding her father’s own dementia, especially as she is a trained nurse. Sally-Ann’s journey, I feel, shows how in its purest form a “medical model” can fail patients, and a person-centred approach might be much positive for all. Prof. Hodges and I feel deeply honoured that Sally-Ann has added her enormously valuable contributions here.

FOREWORD TO ‘LIVING WELL WITH DEMENTIA’ BY SALLY-ANN MARCIANO, PROJECT SPECIALIST, SKILLS UTILISATION PROJECT, SKILLS FOR HEALTH, BRISTOL.

I feel a tremendous honour that I have been asked to write a foreword to Shibley’s outstanding book. I am not an academic but I am a nurse, whose wonderful father died of Alzheimer’s in September 2012. Nothing during my training or nursing career could have prepared me for the challenge that came with supporting my mother in my father’s journey with dementia. I have never met Shibley in person, which makes being asked to write this even more special. What we do have in common, however, is real passion for raising profile of dementia and a hope that we can – one day –improve care for all those living with dementia.

Many people with dementia will live for many years after their diagnosis, and it should be everyone’s ambition in health and social care to ensure that those living with dementia do so as well as possible for all of the remaining years of their life. Diagnosis is just the start of the journey, and, with that, should come full care and support to allow those with dementia to live where they wish, and with their closest present every step of the way.

Sadly my father’s experience revealed a system where no one appeared to take direct responsibility for his care or support. He was, rather, classified as a “social care problem”, and as a result, he had to fund his own care. Even when he was dying, his care was classified as “basic” so that he did not even qualify for funded health care. Our only visit was once-a-year from the memory nurse, and, as his condition declined, my once intelligent, articulate father, who did not even know my name towards the end, needed total care.

Dementia of Alzheimer type destroyed his brain so badly that my father was unable to feed himself, mobilise, or verbalise his needs. He became totally dependent on my mother 24/7. As the condition advanced, my father became increasingly frail, with recurrent chest infections due to aspiration from swallowing difficulties. Each time the GP would be called out, antibiotics prescribed, and so the cycle would begin again. As a nurse, I wanted to see proactive management of my father’s condition. The system locally, however, was quite unable to provide this service. I feel that the dementia of Alzheimer type is a terminal condition, and, as such, should be treated like other similar conditions in care models. What we instead experienced was a “reactive “system of care where the default option was admission to hospital into an environment where my father would quickly decline.

Dementia awareness and training amongst staff must be better; many staff within health and social care will come into contact with people living with dementia as part of their everyday work. That is why I am so excited about Shibley’s book. It is written in a language that is easy to read, and the book will appeal to a wide readership. He has tackled many of the big topics “head on”, and put the person living with dementia and their families at the centre of his writing. You can tell it is written by someone who has observed dementia, has seen its joy, but also felt the pain.

My father was cared for at home right up until he died, mostly through the sheer determination of my mother to ensure she fulfilled his wishes. Not everyone is so fortunate, and for these individuals we really need to be their champion and advocate. Everyone should be allowed to live well with dementia for however long that may be, and, with this book, we can go some way to making this a reality for all.

Sally-Ann Marciano (@nursemaiden)

Bristol, England, United Kingdom

August 8th, 2013

Foreword to my book ‘Living well with dementia’ by Prof John Hodges

This is the Foreword to my book entitled ‘Living well with dementia‘, a 18-chapter book looking at the concept of living well in dementia, and practical ways in which it might be achieved. Whilst the book is written by me (Shibley), I am honoured that the Foreword is written by Prof John Hodges.

Prof Hodges’ biography is as follows:

John Hodges trained in medicine and psychiatry in London, Southampton and Oxford before gravitating to neurology and becoming enamoured by neuropsychology. In 1990, he was appointed a University Lecturer in Cambridge and in 1997 became MRC Professor of Behaviour Neurology. A sabbatical in Sydney in 2002 with Glenda Halliday rekindled a love of sea, sun and surf which culminated in a move here in 2007. He has written over 400 papers on aspects of neuropsychology (especially memory and languages) and dementia, plus six books. He is building a multidisciplinary research group focusing on aspects of frontotemporal dementia.