Home » Posts tagged 'integrated care'

Tag Archives: integrated care

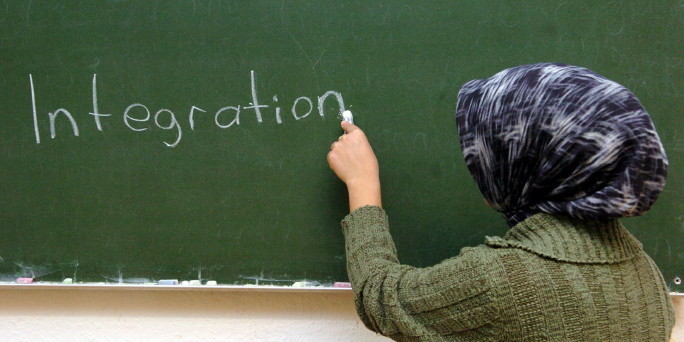

Can the English NHS enter a ‘period of calm’ if it wishes to introduce integrated care?

Sir David Nicholson, KCB, CBE, is Chief Executive of NHS England.

In 2010 Nicholson jokingly described NHS reform plans, the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012), as the biggest change management programme in the world – the only one “so large that you can actually see it from space.”

Andy Burnham MP gave a speech to The King’s Fund on 24 January 2013, entitled “‘Whole-Person Care’ A One Nation approach to health and care for the 21st Century”.

And the Conservative Party, with Jeremy Hunt MP as Secretary of State for Health, have been eyeing up ‘integration‘ too.

So, like many areas of policy such as the private finance initiative, personal budgets or ‘efficiency savings’, there might be considerable consensus amongst the main political parties about implementing a further transformational change in the English NHS.

In that famous King’s Fund speech, Burnham comments, “Second, our fragile NHS has no capacity for further top-down reorganisation, having been ground down by the current round. I know that any changes must be delivered through the organisations and structures we inherit in 2015. ”

This is coupled with, “While we retain the organisations, we will repeal the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and the rules of the market.”

The Health and Social Care Act (2012) as a legislative instrument, whatever the political bluster, had three main legislative aims.

It aimed to implement competitive tendering in procurement as the default option, thus expediting transfer of resources from the public sector to the private sector; it beefed up the powers of the economic regulator (“Monitor”) for this “market”; and it produced a preliminary mechanism for the managed decline of financially unviable entities in the NHS.

Therefore repealing the Act can be argued as a necessary and proportionate move for taking out the ‘competition jet engines’ of the NHS “market”.

Experience from a number of jurisdictions provides that the legal challenges in allowing integration (and bundling) within the framework of competition law are formidable.

There is a clinical case for integrated care, in allowing more co-ordinated care of the person across various disciplines, for example medical, psychiatric or social, for both health and disease.

If community services are ‘wired up’ with hospital services, provided that community services are not starved of money at the same time as hospital services, there is a good rationale in that the health of certain people, followed closely in the community, might not freefall so badly that they require admission to a medical admissions unit.

There is also a financial argument that integrated or whole person care might work, but clearly no political party will wish to prioritise this ahead of quality of clinical care, particularly given the current tinderbox of cuts in medical and social care.

But whichever way you look at it, ‘whole person’ care involves a huge cultural change; this has repercussions for how all professions conduct themselves in their care, especially with regards to community care, and has consequences for training of staff in NHS England.

And it is impossible to think that, whichever political party ultimately becomes responsible for introducing a whole person or integrated care approach, it won’t cost money.

For example, setting up the infrastructure for data sharing, whether clinical or for the purposes of unified budgets, has a long history of being expensive.

Estimates of the cost of the reorganisation just gone are a bit confused, but they tend to range between £2.5 and £3 bn.

The risk of turbulence can be, to some extent, mitigated against by known people at the helm, such as Andy Burnham or Liz Kendall, but the last thing the general public will wish is another period of massive upheaval.

It can be argued that these changes are ‘a good idea’, and it’s only a question of explaining the benefits to the general public, but, following the Health and Social Care Act and caredata, the track record of this current Government is nothing to write home about.

Twitter: @legalaware

Frailty: a critical test in reversing a ‘Fragmented Illness Service’ to a ‘National Health Service”?

Professionals intuitively recognise “frail” older people as more shrinked, and slowly moving. This phenotype is beautifully described by the Finnish painter Helene Schjerfbeck in the self-portraits up to her ninth decade. Increasingly, there has been a welcome policy move in recognising older individuals as a really valuable part of Society. The emphasis should be on ‘living well’, even with comorbidities. Some have rightly attacked blaming the ‘woes’ of the NHS on “the ageing population”.

The lack of definitive diagnostic criteria for ‘frail people’ through DSM or ICD has been a stumbling block, but professionals tend to recognise frail individuals when they see them. The thing not to do is to label all people who are above a certain age as “frail”: there are for example very many able and remarkably able people in their 80s and 90s.

And yet policy has failed to tackle this across many generations in English health policy, because other issues have been considered more urgent, such as A&E “waits”. When one problem appears to be getting solved, another one starts up. Some patients may feel that they will get a ‘better deal’ from a Trust which is observing the 4-hour wait, and prefer to be “blue-lighted” in an ambulance, than to wait for a more appropriate social care referral. Geriatricians are not considered the ‘cinderella service’ of the National Health Service, and care of the elderly wards have not traditionally been considered attractive for ‘high flying’ nurses or doctors, it is sometimes claimed.

This issue is not insubstantial. Out of an acute medical take of about 40-60 patients in one 24 hour period in a busy DGH or teaching hospital, by the law of averages, a handful will be ‘frail’ and then branded ‘social’. However, the needs of such patients should not be seen as a bureaucratic, administrative exercise on the acute medical take. These patients are important, as they are vulnerable for future ‘events’ involving acute medical care in the National Health Service (fragile may be a more physical counterpart of lack of resilience in wellbeing.) Clarity of vision and leadership are both critically needed. General Practitioners will often not need to visit a frail patient at home, unless something goes wrong. And yet when a frail patient ends up in hospital, say from having fallen over but not due to an obvious medical problem, the notes can be voluminous and unintelligible. At this point, the person becomes medicalised and gets plugged into the system at full force. So here is the first problem – when such a person ends up hospital, the communication between medical, psychiatric and social care services can be extremely poor. The care of the ‘frail person’ will be therefore a test case for the success of an integrated care service, when it finally appears.

All this does not mean ignoring the medical needs of the patient, but with a less ‘last minute approach’ investigations can be planned, like a 24-hour-tape or ECG if it is considered that a person is at risk of falling, for example. Tackling frailness indeed is what a person-centred care is designed for, some might say, and would help to enhance the dignity and perceived importance of care in older life. As both the Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Psychiatrists embrace ‘whole person care’, and while SCIE continue to lead on ‘personalisation’, the hope is that the person will be given proper attention in a less panicked way. This would help enormously on steering the “National Health Service” away from a situation where it becomes a lass-minute “Fragmented Illness Service”

The individual gets better ‘whole person care’. And it will in the long run also save money.

Integrated care – there's an app for that! A hypothetical case study.

Innovation and integrated care

Andrew Neil reminded us this morning on ‘The Sunday Politics’ that there are currently around 4 million individuals who don’t have access to the internet. Prof Michael Porter, chair of strategy at the Harvard Business School, has for a long time reminded us that sectors which have competitive advantage are not necessarily those which are cutting-edge technologically, but his colleague Prof Clay Christensen, chair of innovation at the same institution, has been seminal in introducing the concept of ‘disruptive innovation’. An introduction to this area is here. The central theory of Christensen’s work is the dichotomy of sustaining and disruptive innovation. A sustaining innovation hardly results in the downfall of established companies because it improves the performance of existing products along the dimensions that mainstream customers value. Disruptive innovation, on the other hand, will often have characteristics that traditional customer segments may not want, at least initially. Such innovations will appear as cheaper, simpler and even with inferior quality if compared to existing products, but some marginal or new segment will value it.

A consortium, led by Frontier Economics, and including The King’s Fund, The Nuffield Trust and Ernst & Young, was appointed by Monitor to consider issues relating to the delivery of integrated care. Their report is here. Under the Health and Social Care Act Monitor has a duty to “enable” integrated healthcare and integrated health and social care. “Integrated care” is a concept that has been defined in many different ways. A recent review of the literature on integrated care by Armitage et al. (2009) revealed some 175 definitions and concepts. There is now a clear consensus that successful integrated care is primarily about patient experience, although all dimensions of quality and cost-effectiveness are relevant. A definition of integrated care that combines the experiential dimension with that of cost and quality means there are potential benefits from integrated care for current and future service users, the public, providers and commissioners. This means that a working definition of integrated care may be around the smoothness with which a patient or their representatives or carers can navigate the NHS and social care systems in order to meet their needs.

According to the International Longevity Centre – UK, the current (non-integrated) health and social care system has several failures. They include:

- Lack of ‘ownership’ for the patient and her problems, so that information gets lost as she navigates the system

- Lack of involvement by the user/patient in the management and strategy of care

- Poor communication with the user/patient as well as between health and social care providers

- Treating service users for one condition without recognising other needs or conditions, thereby undermining the overall effectiveness of treatment

- Decisions made in the social care setting affect the impact of health care treatment, and vice versa

At the heart of this new model of care is the need to better integrate services between providers around the individual needs of patients and service users. As The King’s Fund’s review of the evidence for integrated care concluded, significant benefits might potentially arise from the integration of services (Curry and Ham 2010), particularly when these are targeted at those client groups for whom care is currently poorly co-ordinated. In the NHS, integrated care could be particularly important in meeting the needs of people with chronic diseases like diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; frail older people who may have several chronic diseases and be in contact with a range of health and social care professionals; and people using specialist services – for example, those involved in respiratory, cardiac and cancer care – where networks linking hospitals that provide these services have contributed to improved outcomes. In some cases integration may even entail bringing together responsibility for commissioning and provision. This form of integration is important because it allows clinicians to use budgets either to provide services more directly or to commission these services from others through ‘make or buy’ decisions. The critical ingredients of integrated care are considered to be: defining the right populations, aligning the right financial incentives to support a variety of diverse healthcare providers (but primarily to ensure the highest quality in patient overall experience), improved accountability for better performance in a more coherent outcome of coordinated care, judicious use of information technology and other knowledge management resources, effective leadership, a collaborative (and competitive where appropriate) culture, patient engagement, and better and more appropriate use of resources according to multi-disciplinary relevance.

In this hypothetical innovation described below, patients, members of CCGs, and healthcare providers have access to a smartphone app called “Integrated care”.

Who is the end user?

A problem with integrated care is that it is likely that the same organisational structures would still exist – albeit with key agents, such as health care provider organisations, healthcare professionals including doctors, clinical commissioning groups representatives, and so on, but a better way of looking at this innovation is where all participants are members of a continuous ‘network’ of innovation; this would help to diminish perception of there being a hierarchy in healthcare, which is a source of considerable inertia in the current English NHS. A version of the app could be available to clinical commissioning group members, or directly to the patient, and of course data are shared with healthcare providers.

The advantage about giving the app directly to the patient would be that the patient himself or herself makes a decision about the care, based on up-to-date information about cost and quality of care (it would be necessary to ensure that accurate data are submitted). The main procedural problem is deciding how much money each person has to play with in a personalised budget – would it be higher or indeed without limit for an individual with multidisciplinary needs or lives a long way from their place of treatment? Indeed, should the budgets be limitless, or should there be some form of rationing in keeping with the finite resources provided by the English economy? Notwithstanding these massive issues, this app would be more in keeping of what the general public understands by “money following the patient”.

Rationale for an app

This app could be based around diseases or conditions, such as dementia, systemic lupus erythematosus, and diabetes, which very often affect more than one bodily system, or more than discipline (for example nurses, doctors, dieticians, physiotherapists, SALT experts). The Department of Health initiated a two-year national programme of pilots to investigate the impact of providing integrated care. The national programme consisted of 16 specific initiatives, including: structured care for dementia, end-of-life care, older people at risk of admissions, long term conditions, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, care for diabetes, and substance misuse.

The Kings Fund/Nuffield Trust Report has emphasised the potential value of an innovation-approach to this problem. They felt a need to allow innovations in integrated care time to embed locally, requiring longer planning cycles. For this innovation change to succeed, providers should be allowed to take on financial risks and innovate as approaches to integrated care often work best when some of the responsibilities for commissioning services are given to those who deliver care. They also set out a more nuanced interpretation of patient choice. Patient choice should be intrinsic to the provision of integrated care, however, it could also be a barrier to integrated care.

It would be hard to see such an app being truly automated, in that it would be inconceivable to think of an individual making a decision about integrated care without help of an appropriate expert. However, having an app supported on the cloud has its advantages. Notwithstanding the usual privacy and security issues (which exist even with online shopping with supermarkets), resources could be scaled according to the needs of the population, and the transfer of information freely across all parts of the network would be virtually instantaneous.

Barriers to integration which the app would seek to overcome:

- Quality of IT and communication system: having separate information systems with different formats for clinical documents and without a common access to service users’ information makes integrated care more difficult (i.e. inter-operability); apps are commonplace on a variety of media including Apple iphones and Google Android phones, and for example different operating systems?

- Risk aversion: health professionals often work under heavy responsibilities and may be over-cautious e.g. when transferring their patients to another organisation, or collaborating with other providers; using an app might itself might be symbolic of embracing a different cultural approach to the more cumbersome (and slower) paper handling of integrative healthcare administration?

- Service users choosing alternative providers: service users have freedom of choice regarding their elected place of care. However, this freedom can create deviations from the planned pathway of care and may cut across attempts to provide integrated care. Regulation has a critical rôle here, if the definition of ‘any qualified provider’ allows as many regulated healthcare providers to enter into a competitive market.

There are still problems that the app would have difficulty in overcoming, namely:

- Governance: it may be unclear who has ultimate clinical and/or organisational responsibility should anything go wrong. That may make individuals reluctant to discharge patients from their care into that of another clinician.

- Clinical practice: differences in how to treat patients between different institutions can mean a lack of consensus and unwillingness to transfer patients from one part of the system to another.

- Cultural differences: driven by some of the issues above but even also by management style, extent of delegation of authority, clarity over objectives and other factors that might affect willingness to share information, resources and service users.

Nonetheless, there are possible advantages of the app:

- Having structured relationships between service providers and with patients – co-location, case management, multidisciplinary teams and assigning patients to a particular primary health care provider

- Using structured arrangements for coordinating service provision between providers – coordinated or joint consultation, shared assessments, and arrangements for priority access to another service

- Using systems to support care coordination – care plans, shared decision support, patient-held or shared records, shared information or communication systems, and a register of patients

- Improving communication between service providers – electronic transfer of data could be facilitated through instant messaging, or audio/video conferencing (like Skype)

- Providing support for patients – access to the most-up-to-date information about the condition, and healthcare providers.

Advantages of integrated care

Integrated Care should improve quality of health care. Quality can have several dimensions and interpretations. However, according to the evidence that we have reviewed, integrated care should improve quality based on four types of benefits:

- Patient experience: according to the NHS Confederation, improving patient experience as a whole is complex. It involves looking at every aspect of how care is delivered, including how the patient comes into contact with the ‘health system’ in the first place.

- Clinical outcome: based on Frommer et al. (1992), a clinical outcome is the “change in the health of an individual, group of people or population which is attributable to an intervention or series of interventions”. It could include lower admission and readmission rates, shorter hospital stay, reduction in the use of hospital beds, shorter recovery periods, etc.

- Patient safety: the Department of Health’s report on patient safety states that healthcare relies on a range of complex interactions between people, skills, technologies and drugs. Sometimes things can – and do – go wrong. While progress has been made, patient safety is not always given the same priority or status as other major issues such as reducing waiting times, implementing national service frameworks and achieving financial balance.

- Cost efficiency: reducing the overall cost of health-related concerns is complicated by defining the scope of such concerns and the extent to which prevention, actual treatment and post-treatment recovery, rehabilitation and re-integration and ongoing support are included in the calculation of costs.

The author is well aware that there are many operational and strategic issues with the implementation of such an app, but the purpose of this article is simply to introduce some basic concepts of integrated healthcare.

An ethos of collaboration is essential for the NHS to succeed

As a result of the Health and Social Care Act, the number of private healthcare providers have been allowed to increase under the figleaf of a well reputed brand, the NHS, but now allowing maximisation of shareholder dividend for private companies. The failure in regulation of the energy utilities should be a cautionary tale regarding how the new NHS is to be regulated, especially since the rule book for the NHS, Monitor, is heavily based on the rulebook for the utilities. The dogma that competition drives quality, promoted by Julian LeGrand and others, has been totally toxic in a coherent debate, and demonstrates a fundamental lack of an understanding of how health professionals in the NHS actually function. People in the NHS are very willing to work with each other, making referrals for the general benefit of the holistic care of the patient, without having to worry about personalised budgets or financial conflicts of interest. It is disgraceful that healthcare thinktanks have been allowed to peddle a language of competition, without giving due credit to the language of collaboration, which is at the heart of much contemporary management, including notably innovation. (more…)