Home » Posts tagged 'insurance'

Tag Archives: insurance

The sting in NHS data sharing is in making insurance contracts void

Even Google gave up on their central database for health information called “Google Health“. Whilst few things are as certain as death and taxes, it is fairly certain that there is big money in big data. Lord Shutt of Greetland, Chair of the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust Ltd. warned, in a foreword on a recent report on “the database state“, that the problem is huge, and as a society we must face up to formidable challenges. There has always been a tough balance in the law between balancing individual rights of privacy and freedom, with the State’s rights of national policy of health and security, for example. Whatever ideological position the Liberal Democrats eventually settle on, it is striking that a Conservative Prime Minister should actually advocate nationalising something.

It is unsurprising that Big Pharma would have welcomed the move. Andrew Witty, the chief executive of GlaxoSmithKline, stated to the Sunday Telegraph he welcomed the data-sharing initiative: “Any action the government takes to improve the environment in this country for life science across these activities is welcome.” The Autumn Statement (2011) had indeed signposted this. It might seem paradoxical that the Department of Health at this time wishes to embark on an initiative to make the NHS “paperless”, at a time when a reorganisation, estimated at £3bn, is currently underway. Patient data, essential for individual patient security, confidentiality and consent, are “rich pickings” for the private healthcare industry, which have not collectively paid to collect this information nor invest in the IT infrastructure of the NHS, but the ethical concerns are enormous. Personalised medicine, dependent on real-time patient information, is “the next big thing” emergency in the pharmaceutical industry, currently keeping stocks of companies very healthy. However, the professional code for Doctors, from the General Medical Council (“GMC”) is very clear on the regulation of patient confidentiality and privacy: this is contained within “Confidentiality” (2009), and clearly guides doctors on the conflicting balance between confidentiality and disclosure.

There are interesting reasons why the operational roll-out of the National Patient Record failed in 2006-7. It is now reported that all prescriptions, diagnoses, operations and test results will be uploaded on to central computers by the end of next year, and, by 2018, all NHS organisations will be expected to be able to share this information with other hospitals, GPs, ambulances and health trusts. Jeremy Hunt hopes local councils will sign up to similar systems, along with private care homes. As with the overall direction of travel of the NHS towards an insurance system where private companies pay “a greater part”, this blurring of the need for patient consent has been insidious.

Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 (originally enacted under Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001), allows the common law duty of confidentiality to be set aside in specific circumstances where anonymised information is not sufficient and where patient consent is not practicable. For example a research study may require access to patient identifiable data to allow linkages between different datasets where the cohort is too large for consent. This would require time limited access to identifiable information where gaining consent from a large retrospective cohort would not be feasible and would require more identifiable data than would be necessary for linkage purposes. However, section 10 of the Data Protection Act (1988) currently allows a right for an individual to prevent damage or distress by data processing. This is indeed conveniently “triggered” by section 259(10) of the Health and Social Care Act (2010), i.e. “[the provision] is subject to any express restriction on disclosure imposed by or under another Act (other than any restriction which allows disclosure if authorised by or under an Act”:

The Secondary Uses Service (SUS) Programme supports the NHS and its partners by providing a single source of comprehensive data for planning, commissioning, management, research, audit, public health and “payment-by-results”, a reimbursement mechanism for acute care payments. It is critical to know whether patients maintain a right to opt out of the SUS database. It should not be the case that NHS patients are denied hospital care if they do not agree to my records being sent to SUS. Steve Nowottny in his “Editor’s Blog” for Pulse, a newspaper circulated to GPs, on 8 January 2013 outlined some important very recent developments:

“That year, Pulse ran a ‘Common Sense on IT’ campaign which highlighted a series of concerns over the consent and confidentiality safeguards in the new system.

“GPs wanted patients to have to give explicit rather than merely implied consent before records were created. Plans to use data within the records for research purposes without explicit consent had Catholic and Muslim leaders up in arms, because they feared the research could be purposes contrary to their faiths, such as abortion or stem cell research.

We revealed that celebrities, politicians and other patients whose information is regarded as sensitive would be exempted from the automatic creation of a Summary Care Record, raising questions about the system’s security. And we reported that patients who did not initially choose to opt out of the Summary Care Record would be unable to have their records subsequently deleted.

At the time, it felt as though the stories, while interesting and concerning, were somewhat theoretical. The Summary Care Record’s deployment to date had been patchy and it was far from certain it would continue. In the meantime, fewer than 1% of patients had bothered to opt out. (Now, with nearly 22 million records created and more than 41 million patients contacted, the figure stands at 1.34%).

But the news today that 4,201 patients had Summary Care Records created without them giving even implied consent – and that they will not be able to have them deleted – reignites the whole debate. Suddenly ‘what if’ scenarios have become reality.”

Tim Kelsey is the NCB’s National Director for Patients and Information – his stated aims are to put transparency and public participation at the centre of a transformation of customer service in the NHS. In a recent lecture, he quoted George Soros who said “our social institutions are imperfect, they should be open to improvement [and that] requires transparency and data“. On-line banking and e-ticketing demonstrate the power of open access to personal data in a safe, secure way – for some reason, heath data is deemed more personal that finance and travel arrangements. Data.gov.uk is an example of his vision for the future – the UK has so much medical data, not only about patients but also genomics and other bioinformatics disciplines. The law currently gives the NCB power to mandate more data flows – Kelsey apparently targets April 2014 to get outcomes-based data flows from primary and secondary care – once achieved, next step is to embrace social and specialist care. So, once the data is “freely available”, it can be made available for public participation – he is investing in a course called ‘Code for Health’, a 3 day course to learn how to develop apps. Data are essential from April 2013, there will be push for on-line interaction with GPs, to realise nationally the benefits seen in pilot areas.

So why should commissioners need access to “personal identifiable data”? It is considered that these may be “good reasons”:

- integrated care and monitoring services including outcomes and experience requires linkages across sources

- commissioning the right services for the right people requires the validation that patients belong to CCGs and have received the correct treatments

- aspects of service planning and monitoring on geographic data basis require postcodes for certain type of analysis

- understanding population and monitoring inequalities

- target support for patients and population groups at highest risk requires data from several sources linked together

- specialist commissioning is commissioned outside local areas and can require wider discussions about individual patients and their associated costs

- ensuring appropriate clinical service delivery and process requires access to records

To enable commissioning, ‘personal identifiable data’ including NHS no, DOB, Postcode data needs to flow to “data management integration centres” (“DMICs”). The DMICs need to have similar powers and controls to the Health and Social Care Act information centres to process data It was known that, in order for processing of PID at DMICs to be undertaken legally, a change in legislation would have been required.

David Cameron has stated explicitly his intention for social care to head towards a private insurance system. As stated in the transcript of the interview with Andrew Marr,

“Well the point that was being made earlier on the sofa by Nick Watt, this is a massive problem – that you know more and more people suffering from dementia and other conditions where they go into long-term care and there are catastrophic costs that lead them to have to sell their homes to pay for that care – it’s right to try and put in place a cap which will then open up an enormous insurance market, so people can insure against that sort of catastrophic loss.”

A longrunning conundrum about where there is such intense interest in ‘raising awareness of dementia’. The idea of having GPs and physicians ‘diagnose’ dementia on the basis of a screening test, without it being called ‘screening’ in name, has not been backed up with the appropriate resource allocation for dementia care elsewhere in the system, including adequate training for junior doctors and nurses crucially involved in actual dementia care. Is this and integration of care an entirely virtuous sociological problem? Integration of care at first sight seems to involve primarily avoidance of reduplication of operations, and better ‘coordinated’ care between health and social care and funding. This is not an unworthy ambition at all. It is well known that the endpoint of the Pirie and Butler “Health of Nations” blueprint for NHS privatisation has a greater rôle for the private insurance market as the endpoint, so it makes complete sense to have a fully integrated IT system which private insurers and the Big Pharma can tap into.

Lawyers will, of course, be cognisant about the added beauty of integration of clinical and financial information. One of the biggest banes of insurance markets is information asymmetry, making calculation of risk and potential payouts difficult. Insurers will argue that calculation of risk is only possible with precise information, clinical commissioning groups are merely “statutory insurance schemes”. It is a long-held belief that private insurers refuse to pay off given the slightest lack of compliance in terms and conditions, but private insurers provide that this mechanism needs to exist to protect them making unnecessary payouts. Failure to disclose medical conditions is an excellent way for private insurers to get out of “paying up”, otherwise known as rescission. Of course, this could be taking the “conspiracy theory” far too far, and these concerns about the use of “big data” otherwise than for a “public good” may be totally unfounded.

You can, nonetheless, mount an argument why the current Government wish to progress with this particular approach to private medical data. The private insurance market and Big Pharma stand to benefit massively, and their lobbying is much more sophisticated than lobbying from GPs, physicians or members of the public. The drive towards all nurses having #ipad3s and all TTOs from Foundation Doctors being sent by broadband to nursing homes may seem utterly virtuous, but there are more significant drivers to this agenda beyond reasonable doubt. On the other hand, it’s simply that healthcare policy is in fact improving for the benefit of patients.

Extremely grateful to the work of Prof Ross Anderson, Chair of Computer Security at Cambridge University, and Phil Booth @EinsteinsAttic on Twitter with whom I have had many rewarding and insightful Twitter conversations with @helliewm.

NHS Privatisation: The end-game

where you see * you can click to the hyperlink to bring you to the original website source of the direct quote.

I was recently reminded of a debacle under a Labour government in 2006 which the Guardian reported as follows*:

“A secret plan to privatise an entire tier of the NHS in England was revealed prematurely yesterday when the Department of Health asked multinational firms to manage services worth up to £64bn.

The department’s commercial directorate placed an advertisement in the EU official journal inviting companies to begin “a competitive dialogue” about how they could take over the purchasing of healthcare for millions of NHS patients. …

The advertisement asked firms to show how they could benefit patients if they took over responsibility for buying healthcare from NHS hospitals, private clinics and charities. The plan would give private firms responsibility for deciding which treatments and services would be made available to patients – and whether NHS or private hospitals would provide them.” (The Guardian)

“How to create money” in the NHS has always been one about denigrating the views of its professional social capital, and thinking about ways of maximising income.

As we approach the ‘E day’, May 7th 2015, when we know that the UK will go to the polls, it is useful to consider now the end-game of NHS privatisation.

False reassurances have been a-plenty.

Privatisation, when you apply common sense, is simply diversion of resources into the private sector from the public sector. Outsourcing (enacted through section 75 Health and Social Care Act (2012) and its regulations) is a key part of that.

But it’s not the full story. You’d have to be a complete idiot to wish to maintain that the NHS is not being privatised.

Some people, it seems, are prepared to perform that rôle.

The end-game

Nearly a year ago, before the section 75 regulations had been discussed in parliament, I introduced here how this somewhat ignored clause would fix the NHS into a competitive market.

I wrote a blogpost on the predictable trajectory of the NHS privatisation which clearly argues that this had started with shifts in policy from the Thatcher and Major governments.

If you want to understand the model, it’s worth tracking it back to the horses’ mouths: Conservative MPs Mr John Redwood and Dr Oliver Letwin.

In a now seminal article, “Opening the oyster: the 2010-1 NHS reforms in England” by academics Dr Lucy Reynolds and Prof Martin McKee for the Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London (2012), known as “Clinical medicine”, the background to this journey to full privatisation is laid bare [Clin Med, April 1, 2012 vol 12 no 2, pp. 128-132.]

Reynolds and McKee argue in their conclusion*:

“Enthoven’s description of the HMO model, which he explicitly stated was at least as problematic but more expensive than the NHS, has somehow been adopted as a blueprint for the privatisation of the NHS. It was recently reported that the newer ‘accountable care model’ now finds favour with the secretary of state for health. This flexible model is a successor to the HMO model, although it is not greatly different in concept or operation. It involves a managed care arrangement in which the private sector primary care gatekeeper receives a subsidy from the government to pay all or part of the individual premiums due for the people registered with it, with the individuals concerned expected to pay any shortfall between the personal budgets provided by government and the amount charged by the accountable care organisation.

… Fulfilment of the longstanding ambition, documented by Redwood and Letwin, to expand private financing of the healthcare system through user contributions is thus now imminent. Enthoven’s reasoned view that market-based healthcare provision is more expensive and less universal than the NHS system consistently has been overlooked. …” (Reynolds and McKee, 2012)

“Commissioning support units” are for the time-being part of the new NHS landscape. Here they are discussed by Veronika Thiel on the King’s Fund website (linking to an article in the HSJ)*:

“Commissioning support units are set to take on important functions in the new NHS structure. They will support clinical commissioning groups by providing business intelligence, health and clinical procurement services, as well as back-office administrative functions, including contract management.” (Thiel, King’s Fund website)

The immediate future steps are something like this:

1. CSUs spun off as private entities, to private equity firms.

2. CSUs provide support to CCGs.

3. CCGs commission services from providers.

4. Each of us given a voucher worth what it is predicted we will cost.

5. We then exercise our choice to find an option that meets our expectations.

6. If the value of our voucher is insufficient, we top it up ourselves.

7. There’s some safety net for the very poor perhaps (and there’s a bit of lee-way here for anti-immigration politics).

8. CCGs compete with each other.

Commissioning support units and private equity

Roy Lilley, a health commentator, only this week reported on the big problem with the CSUs in an article entitled “Trojan Horse”*:

“The DH has a problem. By 2016 CSUs have to be off the NHS’s books as their grace period as chaperoned NHSE organisations comes to an end. They could be taken over and run by their staff, as a social enterprise or the private sector encouraged to buy-in. The usual suspects, Capita, Serco, Atos, and McKinsey are having a look. KPMG are not. …

Will they make money? Not now, not next year, but assuming there is no political upheaval in 2015, CSUs, as a long term punt, with payback measured in years not months might make them Primary Care’s Trojan Horse.” (Roy Lilley)

On 3 November 2013, the Financial Times had reported the following*:

“The NHS has approached private equity companies about taking over organisations that help buy billions of pounds of services for hospitals and GPs. The talks focus on the 19 commissioning support units (CSUs) set up last year to provide services to the new doctor-led commissioning groups that spend more than two-thirds of the NHS budget. …

CSUs were created as part of contentious healthcare reforms pushed through by the coalition government last year in the teeth of fierce opposition from Labour and much of the medical profession. Although the turnover of the 19 units range from just £21m to £62m a year, together they employ nearly 9,000 staff, designing health services and providing back office IT, procurement and payroll services to clinical commissioning groups. While the CSUs are subsidised by the NHS, they are expected to become self-sufficient profitmaking businesses or form joint ventures with the public or private sectors by 2016.” (Financial Times)

The public’s lack of appetite for privatisation

The public generally think that all privatisations work with a lot of publicity like the BT or Royal Mail one. Where ‘word-of-mouth advertising’ has usually effective (e.g. “Tell Sid”), campaigns anti-NHS privatisation can all too easily go viral (pooled efforts of NHS activists on the section 75 regulations, which saw withdrawal of the original statutory instrument.)

The situation of the ongoing NHS privatisation, across a number of successive UK administrations, is fundamentally different, as in this case the whole project can only work if the public do not realise that they are being duped. Many organisations, politicians, and other leaders can rightly share the blame for not been truthful about the situation. What in fact is most incredible that the process of privatisation of the NHS has been so vehemently denied by politicians and think-tanks, when it is all so incredibly blatant.

There are still a few ‘barriers’ to the ultimate end described below, but these are not impossible for the ‘privateers’ given the right environment.

These include the election of a government which can implement the final steps (this could be any of the main political parties based on their past performance), a NHS IT system ‘fit for purpose’, a method of allocating funds for CCGs depending on individuals’ contributions, a method for allowing top-up payments, to name but a few. However the privateers will be encouraged by the privatisation ‘progress’ which has been made in the last few years.

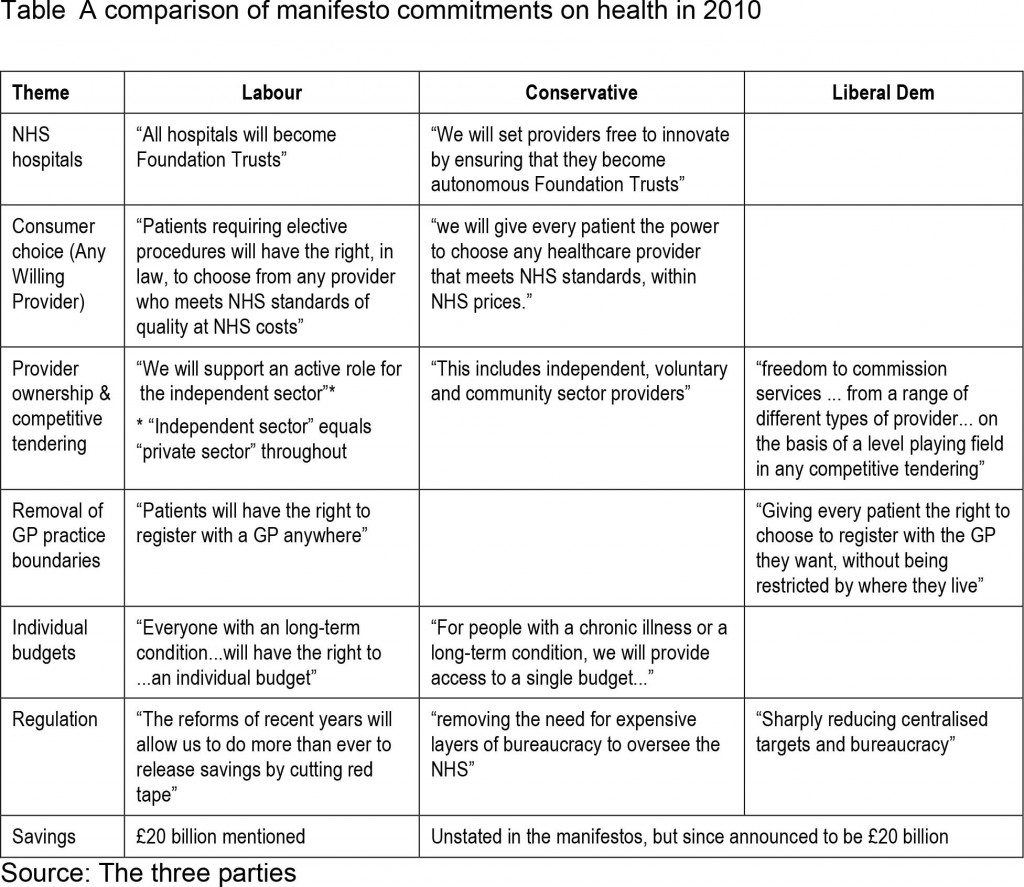

Appetite for privatisation had failed to increase prior to the last election, despite little manoeuvres like the NHS logo available to private companies to make it hard for patients to distinguish between services provided by them and the NHS proper; and permitting private hospitals to compete to sell whichever procedures they wish to offer. With all three main major political parties having converged on the market, there was barely a cigarette paper’s difference between these parties from which to choose.

Arguably, however, it would be quite unfair to blame unilaterally the UK Labour Party with the benefit of hindsight. Labour remain adamant that they would never have enacted a statutory instrument such as the Health and Social Care Act (2012). There is no indication that Labour had intended to publish a similar Act from Hansard. Furthermore, they did consistently fight tooth-and-nail against the Act in the lower House and the House of Lords.

Clinical-based commissioning

Doctors have been sold a bit of a pup, but the media and politicians were adamant that GPs would have a greater rôle in commissioning.

A starting point for understanding the relevance of commissioning to the privatised NHS is the famous Adam Smith Institute’s Pirie and Butler document, which includes a description of their proposed final phase of a switch from a classic NHS to a US-style system. Madsen Pirie and Eamonn Butler are the well known free market gurus at the Adam-Smith Institute. Their entire document reads like a promotion glossy for privatisation, completely bereft of evidence-based academic references.

The end point is a US-style health maintenance organisation (HMO).

The problem of starting new system such as Health Maintenance Organisations is largely avoided by keeping patients with their present GP. In theory, the resources go to the CCG selected by the doctor, although the ultimate choice lies with the patient, who can change CCG by going to a doctor registered with another one. The resources are thus supposed to be directed to the CCGs which are most favoured by doctors and patients.

Nonetheless, it is the CCG who holds the power. As such, CCGs don’t need to have any medical expertise.

Even a Tory MP, Dr Sarah Wollaston, has drawn attention* to how CCGs appear to have gone ‘gun-ho‘ in privatising when David Bennett from Monitor had not felt such a need:

“The existing guidance is widely ignored. David Bennet (sic), the Chief Executive of the regulator Monitor, has set out in a number of settings that commissioners are putting too many services out to tender and yet the waste of resources continues. Perhaps because no commissioners have the spare cash to fight a legal challenge themselves.” (Dr Sarah Wollaston’s blog)

That is why this from Earl Howe is pure ‘smoke and mirrors’ from when the section 75 Regulations were being discussed (shared by Clive Peedell of the National Health Action Party):

Resource allocation and “vouchers”

There are various accounts of how resource allocation works in the NHS, and indeed one of the challenges of understanding NHS privatisation is understanding new parts of the puzzle as they fall into place. NHS England, as Baumann offered in his Health Select Committee evidence this week, will be describing yet another configuration of this formula in December which is apparently going to factor in inequality as well.

In this model, each individual would receive from the state a health voucher, equivalent in value to what he or she approximately is currently ‘consuming’. Making the maths work is of course made a lot easier if the allotted budgets have already been worked out through implementation of ‘personal health budgets‘.

The voucher can be used towards the purchase of private health insurance or exchanged for treatment within the public sector health system. This can easily be sold on the basis of ‘equity’ – that each person has equal access to a ‘National Health Service’ – whereas people actually have access to an inter-tradeable insurance scheme.

Those who opt into private insurance can use the voucher to pay their premiums, and the insurance companies then collect the cash value of the “voucher” from the government. This is the most odd aspect of the model, but easy if you understand the apparent ease with which successive Conservative governments have effectively provided state benefits for their private sector colleagues (see recent outsourcing debacles across a number of sectors.)

The issue of co-payments had been kicked into the long grass.

Sir David Nicholson gave a further reassurance recently (irony klaxon) that it was unlikely that such payments would be introduced imminently on a BBC Radio 4 discussion programme called “Costing the NHS“.

People who decide that health care is particularly important to them are free to add to the amount covered by the voucher and thus purchase more expensive forms of insurance, perhaps covering more unlikely risks or providing superior standards of comfort or convenience.

This is where the right-wing are able to allow for the fact that people who want to pay more can. People on the centre and left, however, interpret this as producing potentially a ‘two tier system’. It is currently not that difficult to find stories of how inadequate the US Medicaid services are currently, and it is a national disgrace of theirs that there are some citizens who are too poor or too ill to be able to afford an insurance-based healthcare.

The voucher would not force people into private insurance, although it certainly makes the option of going private instantly available to everyone. Those who want to use the state service will continue to receive it, their voucher being their ticket to free treatment just as their national insurance number is at the moment.

The distinction between a public health service which does what it can on a take-it-or-leave-it basis, and a private system for the rich which offers choice and competition begins to overlap.

The demise of the CCGs

“Integration” is the standard weapon in the war of words which tries to legitimise the smuggling of the US health insurance industry into running the NHS. The insurance/voucher system fits snugly into such “integration” (or even “whole person care”), and could see one arm of the system (e.g. “universal credit”) enmeshing with another (e.g. “personal health budgets”) for whole person care. This is of course is hugely dangerous without the proper safeguards. Successsive governments have tried so hard to shore up the NHS IT system, under various pretences such as “the paperless NHS”, precisely for this purpose.

A possible relationship between universal credit and whole person credit was mooted here in the mysteriously insightful article by Jennie Macklin and Liam Byrne.

Why are MasterCard so keen on working on payment mechanisms? This article explores possibly why.

The public sector CCGs, taking responsibility for total health care of NHS patients, are not too far removed in structure from private insurance and management bodies. The funds for premiums are publicly provided, but the same competition and incentives operate, and the same choices are made available. Experience, however, from the US is that it is difficult for a patient to sue a CCG directly if a problem arises.

So the Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) still remains a favourite means of achieving the NHS privatisation ‘end game’. The CCG format simply lays the groundwork and the basis for further changes at a later stage.

One of the first things to happen is that CCGs receive their population-based allowances. Whilst it is likely that this will be done on an incremental basis from what the current allocations might be, as CCGs become more sophisticated, they might make use of other techniques such as ‘the dementia prevalence calculator‘ which appears to have achieved somewhat of a pedestal status in dementia public health.

Another trick in the ‘registration process’ is hoping that some members of the public never register and so never receive their allowance. This is known to be a trick of the Department of Work and Pensions which have often failed to notify benefit claimants that their welfare benefits have come to an end.

CCGs might become themselves sitting ducks for becoming insolvent.

The Department of Health will have to conjure up increasingly imaginative methods of arranging CCG funding sharing so as to not make them look like cuts (and find a mouthpiece to publicise them).

A final change of direction for the NHS hoped by some?

Nick Seddon has recently been reported to have caused some controversy by proposing NHS cuts and GP charges. He of course has been the Deputy Director of the think-tank Reform. In 2008, published during the time of a Labour government, Reform produced a pamphlet entitled, “Making the NHS the best insurance policy in the world “.

Their “top recommendations” included the following*:

“These incentives could be introduced by changing the National Health Service to a National Health Protection System. Taxpayer funding and guaranteed access would continue, but individuals would be empowered to decide which approved Health Protection Provider to use. Custody of individual health outcomes would be made independent; it would no longer be in the hands of politicians.

This would mean the following for individuals:

- A “healthcare protection premium” of £2,000 per year would be paid out of general taxation, equivalent to the current NHS cost per individual in England. NB this is similar to the cost of health insurance in France and the Netherlands.

- A choice of where to spend the health protection premium, between Health Protection Providers (HPPs). Coverage for a wide, core level of health treatment, including all essential operations and treatments.

- Extra services, such as gym membership, and rebates for healthy living, for example smoking cessation, offered by HPPs to attract customers.

- Regulation of HPPs by government to ensure they reach minimum standards.

- The ability to top-up their premium to have extra services such as certain drugs, cosmetic surgery or better accommodation in hospitals. People in the UK already value their healthcare enough to spend £1,600 per family per year on health and fitness.The current Departmental review of top-up payments for cancer drugs and the draft EU Directive on cross-border healthcare are likely to lead to greater clarity over what individuals are entitled to and to a new market in insurance for top-up payments.

- Guaranteed accident and emergency cover through a general agreement with insurers, on the model of the Dutch compulsory insurance system.

Because of the positive developments in the UK, this is a task of evolution rather than revolution which could be complete in three to five years. The key steps would be turning Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) into Health Protection Providers; allowing other insurers to join the system; and defining the core entitlement to healthcare.

In January 2008 the Prime Minister described the NHS as “the best insurance policy in the world”. That is the right idea. It means radical change, to combine universal coverage with the focus on the patient evident in other countries. Success would see the UK rejoin the top rank of international health systems and become again the envy of the world.” (Reform Report, 2008)

I remember when I was once in a cab in London, and the cabbie was telling me how, for some private care his wife had received, the insurer had refused to pay for certain aspects of after-care. This is somewhat reminiscent for me of the following criticism made by Reynolds and McKee (2012) in relation to the Reform report*:

“This plan is alluded to in the 2010 white paper in the opaque phrase ‘money will follow the patient’. This refers to the impending roll-out of personal health budgets for all those registered with the NHS. These have been greeted with enthusiasm by patient groups, somewhat strangely when one considers that the NHS currently undertakes to cover all costs of care, whereas the concept of a finite budget implies that it is possible that the actual costs of care could exceed that budget, leaving the patient to cover the excess.” (Reynolds and McKee, 2012)

Andy Burnham MP: “I admit it – we let the market in too far”

Andy Burnham MP is reported on June 9th 2013 as saying the following*:

“When Shadow health lead Andy Burnham MP visited Lewisham the previous evening, he began his speech:

“I admit it – we let the market in too far and now on the 65th anniversary of the NHS we need to renew our commitment to Bevan’s NHS: public service over privatisation; collaboration over competition and people’s wellbeing before self-interested profit.”” (“Left Foot Forward” blog)

This was an important statement to have made.

And Burnham is reported in the same article as wishing to put a stop to the neoliberal firestorm of hospital reconfigurations:

“Later in the day Burnham left his Lewisham audience in no doubt as to his feelings and his intention :

“I give my full support and backing to Lewisham Hospital. 25,000 people marching through the streets is a remarkable achievement. We support the campaign.””

Conclusion

It’s all fairly predictable.

Or so it might appear. You could mount an argument that the present system is far better (having “liberalised” the NHS with non-NHS providers) than having an insurance-based system.

Indeed, indeed Andrew Lansley, the former Secretary of State for Health preceding Jeremy Hunt in the current government, claimed to be opposed to be against such a method of funding the NHS when the Bill was beginning to reach a climax in its discussions.

(see beginning of this video)

Aside from who exactly is in the market post 2015, whether it’s Andy Burnham MP’s “NHS preferred provider” or the Coalition’s “Any qualified provider”, it’s still of concern that there’s still a market. As a first step, Burnham in October 2012 asked for a block on the further ‘roll out’ of “any qualified provider”.

There’s no ‘conspiracy theory’ about it.

For anyone with a training in business and commercial or corporate law, it’s dead obvious.

If you wish to look at what we might be heading to, this overview of the ‘current problems’ of the US healthcare system is a good introduction.

‘Competition’ was used to crowbar the market in. Everyone knows that. People who aggressively pimped competition as a means of improving quality know exactly how faulty their reasoning was (see my previous blogpost). Unfortunately this has done massive damage to English health policy.

This video’s quite useful as it approaches some topics which will are likely to become inevitable for us in this jurisdiction, if we should decide to go down this route: what the process of transformation will cost, how the insurance packages are likely to have to be controlled, competition between CSUs and competition between CCGs in the private market (we know quite how successful competition has been in the energy market), what clinical services will still become out-of-scope, and so on.

The current ‘state of play’ is that Labour has stated categorically to repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012) on many occasions. This is a determined attempt to ‘turn back the tide’ on NHS privatisation, which is a highly popular move amongst potential Labour voters.

Specifically, Labour wishes to put the stuff on competition in part 3 of the Act into reverse. Both Andy Burnham MP and Ed Miliband MP have stated their intention for this independently. Andy Burnham MP is reported as recently as 25 September 2013 as emphasising that he will end ‘fast track privatisation’.

A shift in emphasis from competition to collaboration will make it difficult to run the NHS as a market based on the rules of EU competition, with the correct adjustments in legislation from the Executive.

Many brilliant NHS activists have had landmark successes in opposing Government policy, too.

Never have the stakes been higher for the NHS with the election of the next UK Government, to take place during the course of May 8th 2015.

Try to talk to someone else about it to see what they think?

Andy Burnham's "whole person care" has a huge academic and practitioner literature, and demands discussion

“Whole-Person Care” was at the heart of the proposal at the heart of Labour’s health and care policy review, formally launched this week, and presents a formidable task: a new “Burnham Challenge”? It may not be immediately obvious to people outside of the field, but whole books and a plethora of academic papers have been written on it. I agree its consideration is very timely, given the special set of challenges which the NHS faces, and it is yet another failure of the national media that this speech has not been discussed at all by the national media. Whatever your particular political or philosophical inclination, it does demand proper scrutiny.

It is described as follows:

“Whole-Person Care is a vision for a truly integrated service not just battling disease and infirmity but able to aspire to give all people a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being. A people-centred service which starts with people’s lives, their hopes and dreams, and builds out from there, strengthening and extending the NHS in the 21st century not whittling it away.”

Andy Burnham did not mention the Conservatives once in his speech yesterday for the King’s Fund, the leading think-tank for evidence-based healthcare policy. He did not even produce any unsolicited attacks on the private sector, but this entirely consistent with a “One Nation” philosophy. Burnham was opening Labour’s health and care policy review, set to continue with the work led by Liz Kendall and Diane Abbott. He promised his starting point was “from first principles”, and “whatever your political views, it’s a big moment. However, he faces an enormous task in formulating a coherent strategy acknowledging opportunities and threats in the future, particularly since he suffers from lack of uncertainty about the decisions on which his health team will form their decisions: the so-called “bounded rationality”. The future of the NHS is as defining a moment as a potential referendum on Europe, and yet the former did not attract attention from the mainstream media.

Burnham clearly does not have the energy for the NHS to undergo yet another ‘top down reorganisation’, when the current one is estimated as costing £3bn and causing much upheaval. He indeed advanced an elegant argument that he would be seeking an organisational cultural change itself, which is of course possible with existant structures. This lack of cultural change, many believe, will be the primary source of failure of the present reorganisation. He was clear that competition and the markets were not a solution.

Burnham identifies the societal need to pay for social care as an overriding interest of policy. This comes back to the funding discussion initiated by Andrew Dilnot prior to this reorganisation which had been kicked into the ‘long grass’. Many younger adults do not understand how elderly social care is funded, and the debate about whether this could be a compulsory national insurance scheme or a voluntary system is a practical one. It has been well rehearsed by many other jurisdictions, differing in politics, average income and competence of state provision. The arguments about whether a voluntary system would distort the market adversely through moral hazard and loss aversion are equally well rehearsed. Whilst “the ageing population” is not the sole reason for the increasing funding demands of all types of medical care, it is indeed appropriate that Burnham’s team should confront this issue head-on.

It is impossible to escape the impact of health inequalities in determining a society’s need for resources in any type of health care. Burnham unsurprisingly therefore suggested primary health and preventative medicine being at the heart of the new strategy, and of course there is nothing particularly new in that, having been implemented by Ken Clarke in “The Health of the Nation” in the 1980s Conservative government. General medical physicians including General Practitioners already routinely generate a “problem” list where they view the patient as a “whole”; much of their patient care is indeed concerned with preventive measures (such as cholesterol management in coronary artery disease). A patient with rheumatoid disease might have physical problems due to arthritis, emotional problems related to the condition or medication, or social care problems impeding independent living. Or a person may have a plethora of different physical medical, mental health or social needs. The current problem is that training and delivery of physical medical, mental health or social care is delivered in operational silos, reflecting the distinct training routes of all disciplines. As before, the cultural change management challenge for Burnham’s team is formidable. Also, if Burnham is indeed serious about “one budget”, integrating the budgets will be an incredible ambitious challenge, particularly if the emphasis is person-centred preventive spending as well as patient-centred problem solving spending. When you then consider this may require potential aligment of national and private insurance systems, it gets even more complicated.

The policy proposed by Burnham interestingly shifts emphasis from Foundation Trusts back to DGHs which had been facing a challenge to their existence. Burnham offers a vision for DGHs in coordinating the needs of persons in the community. Health and Well-Being Boards could come to the fore, with CCGs supporting them with technical advice. A less clear role for the CCGs as the statutory insurance schemes could markedly slow down the working up of the NHS for a wholesale privatisation in future, and this is very noteworthy. Burnham clearly has the imperfect competition between AQPs in his sights. Burnham is clearly also concerned about a fragmented service which might be delivered by the current reforms, as has been previously demonstrated in private utilities and railways which offer disproportionate shareholder value compared to end-user value as a result of monopolistic-type competition.

The analysis offered by Andy Burnham and the Shadow Health team is a reasonable one, which is proposed ‘in the national interest’. It indeed draws on many threads in domestic and global healthcare circles. Like the debate over EU membership, it offers potentially “motherhood” and “apple pie” in that few can disagree with the overall goals of the policy, but the hard decisions about how it will be implemented will be tough. Along the way, it will be useful to analyse critical near-gospel suggestions that competition improves quality in healthcare markets, if these turn out to be “bunkum”. Should there be a national compulsory insurance for social care? How can a near-monopolistic market in AQPs be prevented? Nonetheless, it is an approach which is well respected in academic and practitioner circles, and is potentially a very clever solution for the NHS, whatever your political inclination, for our time.