Home » Posts tagged 'English health policy' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: English health policy

Can you divide hospital Trusts into "good" and "bad" hospitals?

Ringfencing or Ring-fencing occurs when a portion of a company’s assets or profits are financially separated without necessarily being operated as a separate entity.

This might be, for example, for regulatory reasons, creating asset protection schemes with respect to financing arrangements, or segregating into separate income streams for taxation purposes.

As an example, Royal Bank of Scotland has said it will not split itself into separate so-called “good” and “bad” banks. RBS will create an internal “bad bank”, ring-fencing £38bn of bad assets – such as loans it does not expect to have repaid. The bank remains 81%-owned by the government following a massive bailout at the height of the financial crisis.

The shares were among the heaviest fallers on the 100 share index in morning trading, falling almost 4% to 353p.

Whilst some people have argued against the validity of the separation between “good banks” and “bad or casino banks”, bad banks might be considered to be those with an excessive amount of risk.

Risk for a hospital could of course be a risk in the clinical setting, or risk in an economic setting (embracing financial risk and business risk.)

A political row has long erupted over the legacy of PFI for the health service as trusts face insolvency.

South London Healthcare, a merger of three hospital trusts, first began having problems spending 14% of its income on repayments to a private finance initiative (PFI).

The government said the financial problems are caused by a PFI scheme signed off under Labour, but Labour said that there are wider financial pressures in the NHS, and PFI also delivered many new hospitals.

Only recently the higher courts have ruled on the legal validity of the reconfigurations at Lewisham, but there are another 20 trusts that have declared themselves financially unsustainable in their current form. The current Care Bill amendment might see a mechanism come into play where NHS Trusts are legally allowed to conduct their reconfigurations.

The component of risk for a hospital which is clinical could in a sense be mitigated against through potentially simple steps.

Various hospitals, many of them busy district generals, have been issued with warnings by the Care Quality Commission after its latest inspections. Each was told it did not have enough staff “to keep people safe and meet their health and welfare needs” — the standard every part of the health service must meet.

Of course some argue that the real discussion is to consider whether the whole budget for the NHS should be ‘ringfenced’.

One traditional strategy for avoiding this discussion, as it is so politically totemic, has been to consider what components of the budget should still remain in scope.

Critics have argued that this has produced, willingly or not, an approach of ‘smoke and mirrors’. How, for example, would an incoming Labour government actually achieve safely combined health and social care funding monies which have come from the NHS and local government funding streams respectively?

Speaking to the Today programme’s Sarah Montague, former Labour health minister Lord Warner gave his view that ‘many elected politicians want to appear to protect the NHS’, but it is time to end the special treatment of the NHS. Warner argues that a 1% increase in “real terms”, to cover rising prices.

The problem with the ring-fence is that it “creates the illusion in the NHS that people don’t have to change the way they deliver services,” he explained.

John Appelby, chief economist of the King’s Fund, said that “pressure in certainly felt by hospitals and staff in the NHS”.

Back to the original issue, it might be possible to ringfence hospitals into ‘good’ and ‘bad’. Whilst the term has been bastardised by the NHS as a justification for closing hospitals in some quarters, part of the rationale for ringfencing has been traditionally to ring-fence liabilities.

For example, when financial entities ‘go bust’, they don’t take the rest of their empire with them.

Now that the privateers have got their way with the market, the public is left with a bundle of ‘economic activities’ comprising the so-called “NHS”.

Cumulatively, the Labour and Conservative Parties have made a mockery of the mantra, “no decision made about me without me.”

Shibley’s CV is here.

Outsourcing has become a policy drug, and they need to kick the habit

If you don’t want to do something, you pay somebody else to do it. Hopefully you pay them peanuts. Doesn’t matter if the actual product or service is a bit shit. Or you could allow somebody else to do it under your identity still. Everyone thinks you’re the author it. But you pay that person a massive mark up so they make a tidy profit. Everyone’s a winner.

For this Government under Frances Maude, Chris Grayling and Jeremy Hunt, “outsourcing” is a drug. They need more of it to get the same kick (an increasing degree of tolerance), and if they don’t outsource something they get nasty withdrawal symptoms. Outsourcing is consider a useful step along the way to privatisation, and of course many less intelligent people have been arguing that the Health and Social Care Act is not privatisation. It is clearly privatisation if you outsource what should be a state-run health service into private hands for profit or surplus, and it is privatisation if you allow up to 50% of income to come from private sources. Both are new developments under this Government. Everyone’s a winner here – especially the hedge funds who are the major institutional shareholders of the private healthcare companies, the private companies who can find through slick procurement bids willing funders, and, of course management consultants, accountants and lawyers who can send a NHS Trust into one of the many detailed insolvency and failure régimes outlined in the Health and Social Care Act (2012). Mind you, there’s not a single clause on ‘safe staffing requirements’ in NHS Trusts, as a necessary and proportionate ‘check and balance’ on overzealous managers inflicting ‘efficiency cuts’ to frontline doctors and nurses. “More for less” is the mantra, and, with the Secretary of State now legally not obligated for the NHS for the first time (but responsible for ‘special measures’ presumably so that he can take control of both lack of patient safety in extreme measures and which private sector advisors can advise), outsourcing is not the next scandal waiting to happen. It is well and truly alive. While the ideological concern has been ‘privatising profits, socialising losses’ a concept coined by Andrew Jackson as far back as 1834 (and maybe the Royal Mail and RSB may be worthy examples to consider here), there is now an added dimension that foreign multinationals can raid the NHS, take over vast bits of it, and their registered offices for tax reasons might be abroad. The line of attack has always been that Doctors and nurses contribute nothing to the ‘wealth’ of this country not being wealth creators (footballers possibly do contribute more in a similar way to “Top Gear” by being potent foreign merchandising exports inter alia). The massive irony is that the tax from profits ends up in foreign jurisdictions, and contribute to the economy of those countries not ours. The resolution of the US-EU Free Trade Agreement, which may or may not include the NHS, will be important here, and there’s still no answer to Debbie Abrahams’ inquiry to my knowledge:

Debbie Abrahams (Oldham East and Saddleworth) (Lab): Will the Prime Minister confirm that the NHS is exempt from the EU-US trade negotiations?

The Prime Minister: I am not aware of a specific exemption for any particular area, but I think that the health service would be treated in the same way in relation to EU-US negotiations as it is in relation to EU rules. If that is in any way inaccurate, I will write to the hon. Lady and put it right.

In an article by Patrick Wintour published recently, Cruddas describes a ‘modern anomie’, a breakdown between an individual and his or her community, and alludes to the challenge of institutions mediating globalisation. Cruddas also describes something which I have heard elsewhere, from Lord Stewart Wood, of a more ‘even’ creation of wealth, whatever this means about the even ‘distribution’ of wealth. One of the lasting legacies of the first global financial crisis is how some people have done extremely well, possibly due to their resilience in economic terms. For example, it has not been unusual for large corporate law firms to maintain a high standard of revenues, while high street law has come close to total implosion in some parts of the country. In a way, this reflects a shift from pooling resources in the State to a neoliberal free market model. The global financial crash did not see a widespread rejection of capitalism, although the Occupy movement did gather some momentum (especially locally here in St. Paul’s Cathedral). It produced glimpses of nostalgia for ‘the spirit of ’45”, but was used effectively by Conservative and libertarian political proponents are causing greater efficiencies. Indeed, Marks and Spencer laid off employees, in its bid to decrease the decrease in its profits, and this corporate restructuring was not unusual. A conservative and a libertarian have several things in common, the most important is the need for people to take care of themselves for the most part. Libertarians want to abolish as much government as they practically can. It is thought that the majority of libertarians are “minarchists” who favour stripping government of most of its accumulated power to meddle, leaving only the police and courts for law enforcement and a sharply reduced military for national defence. A minority are possibly card-carrying anarchists who believe that “limited government” is a delusion, and the free market can provide better law, order, and security than any goverment monopoly.

Essentially a libertarian would fund public services by privatising them. In this ‘brave new world’, insurance companies could use the free market to spread most of the risks we now “socialise” through government, and make a profit doing so. That of course would be the ideal for many in reducing the spend on the NHS, to produce a rock-bottom service with minimal cost for the masses. And to give them credit, the Health and Social Care Act was the biggest Act of parliament, that nobody voted for, to outsource the operations of the NHS to the private sector, which falls under the rubric of privatisation. Outsourcing is an arrangement in which one company provides services for another company that could also be or usually have been provided in-house. Outsourcing is a trend that is becoming more common in information technology and other industries for services that have usually been regarded as intrinsic to managing a business, or indeed the public sector. Many expected the election of the present government to herald a more determined approach to outsourcing public services to the private sector. Initially came the idea of the “big society”, with its emphasis on creating and using more social enterprises to deliver public services, but the backers for this new era of venture philanthropism were not particularly forthcoming. The PR of it, through Steve Hilton and colleagues, was disastrous, and even Lord Wei, one of its chief architects, left. No one in the UK likes the idea of domestic jobs moving overseas. But in recent years, the U.K. has accepted the outsourcing of tens of thousands of jobs, and many prominent corporate executives, politicians, and academics have argued that we have no choice, that with globalisation it is critical to tap the lower costs and unique skills of labour abroad to remain competitive. They argue that Government should stay out of the way and let markets determine where companies hire their employees. But is this debate ever held in public? No, there was always a problem with reconciling the need for cuts with an ideological thirst for cutting the State. Here in the UK, in 2010, the government indicated that it wanted to see new entrants into the outsourcing market, and the prime minister visited Bangalore, the heart of India’s IT and outsourcing industry, for high profile meetings with chief executives of companies such as TCS, Infosys, HCL and Wipro. Nobody ever bothers to ask the public what they think about outsourcing, but if Gillian Duffy’s interaction with Gordon Brown is anything to go by, or Nigel Farage’s baptism in the local elections has proved, the public is still resistant to a concept of ‘British jobs for foreign workers’. However, it is still possible that the general public are somewhat indifferent to screw-ups of outsourcing from corporates, in the same way they learn to cope with excessive salaries of CEOs in the FTSE100. The media have trained us to believe that unemployment rights do not matter, and this indeed has been a successful policy pursued by the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. People do not appear to blame the Government for making outsourcing decisions, for example despite the fact that the ATOS delivery of welfare benefits claims processing has been regarded by many as poor, the previous Labour government does not seem to be blamed much for the current fiasco, and the current fiasco has not become a major electoral issue yet.

And the list of screw-ups is substantial. G4S – the firm behind the Olympic security fiasco – has nowbeen selected to support the Police Service of Northern Ireland at the G8 Summit next month. Despite the company’s botched handling of the Olympics Games contract last summer, G4S has been chosen to supply 450 security staff for the event at Lough Erne, County Fermanagh The leaders of the world’s eight wealthiest countries are expected in Fermanagh on June 17 and 18. Meanwhile, medical assessments of benefit applicants at Atos Healthcare were designed to incorrectly assess claimants as being fit for work, according to an allegation of one of the company’s former senior doctors has claimed. Greg Wood, a GP who worked at the company as a senior adviser on mental health issues, said claimants were not assessed in an “even-handed way”, that evidence for claims was never put forward by the company for doctors to use, and that medical staff were told to change reports if they were too favourable to claimants. Elsewhere, Scotland’s hospitals were banned from contracting out cleaning and catering services to private firms as part of a new drive towards cutting the spread of deadly superbugs in the NHS. There were 6,430 cases of C. difficile infections in Scotland in one year recently, of which 597 proved fatal. The problem was highlighted by an outbreak of the infection earlier this year at the Vale of Leven hospital in Dunbartonshire which affected 55 people. The infection was identified as either the cause of, or a contributory factor in, the death of 18 patients.

Whatever our perception of the public perception, the impact on transparency and strong democracy merit consideration. As we outsource any public service, we appear to risk removing it from the checks and balances of good governance that we expect to have in place. Expensive corporate lawyers can easily outmanoeuvre under-resourced government departments, who often appear to be unaware of the consequences, and this of course is the nightmare scenario of the implementation of the section 75 NHS regulations. Even talking domestically, where contracts privilege commercial sensitivities over public rights, they can be used to exclude the provision of open data or to exempt the outsourcer from freedom of information requests. Talking globally, “competing in the global race” has become the buzzword for allowing UK companies to outsource to countries that do not have laws (or do not enforce laws) for environmental protection, worker safety, and/or child labour. However, all of this is to be expected from a society that we are told wants ‘less for more’, but then again we never have this debate. Are the major political parties afraid to talk to us about outsourcing? Yes, and it could be related to that other ‘elephant in the room’, about whether people would be willing to pay their taxes for a well-run National Health Service, where you would not be worried about your local A&E closing in the name of QUIPP (see this blogpost ). Either way, Jon Cruddas is right, I feel; the ‘modern anomie’ is the schism between the individual and the community, and maybe what Margaret Thatcher in fact meant was ‘There is no such thing as community’. If this means that Tony Blair feels that ‘it doesn’t matter who supplies your NHS services’, and we then get invasion of the corporates into the NHS, you can see where thinking like this ultimately ends up.

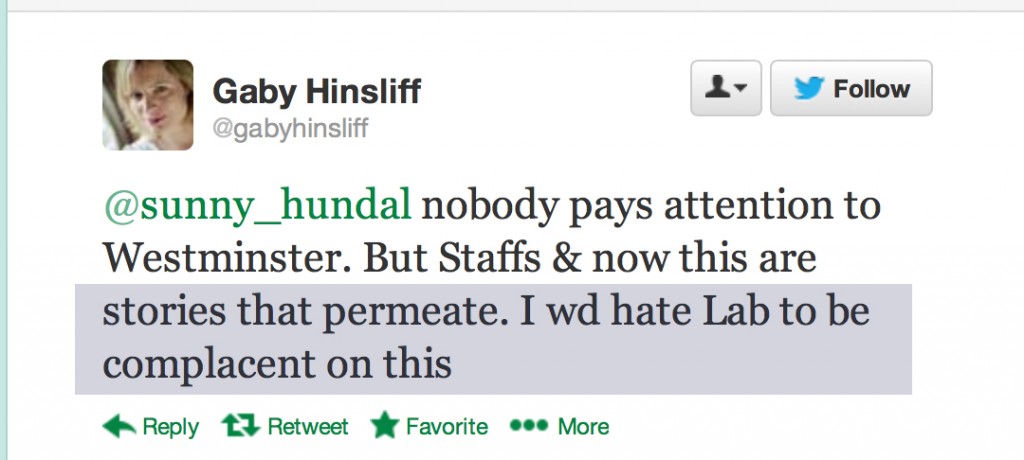

Politically, outsourcing vast amounts of the National Health Service is a big mistake. Take for example the scenario of what happens when something goes wrong. Will you get your money back? The lack of responsibility of the private sector shows how the NHS has to bail out the surgical mistakes of PIP breast implants. The State, evil though it is, does make a habit however of bailing out the private sector, as we all remember from the £860 bailout for the banking industry. It seems like a ‘cost saving’, but it clearly isn’t, in the same way that the private finance initiative has become a ‘cash cow’ for corporates. The essence of NHS policy is not to let the policy lunatics take over, in this case people with clearly vested interests having more impact on policy than professionals in the field. Part of the problem is that there is a lot more in common for Conservative and Labour policies, and indeed this is contributing to a growing sentiment that Labour is becoming complacent on the NHS (tweet by @gabyhinsliff):

Time will tell whether such fears will indeed materialise.