Home » Posts tagged 'English health policy'

Tag Archives: English health policy

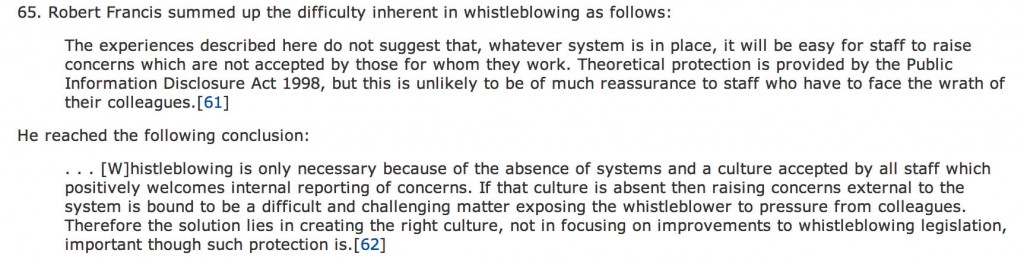

Foreword to my book 'Living well with dementia' by Prof John Hodges

This is the Foreword to my book entitled ‘Living well with dementia‘, a 18-chapter book looking at the concept of living well in dementia, and practical ways in which it might be achieved. Whilst the book is written by me (Shibley), I am honoured that the Foreword is written by Prof John Hodges.

Prof Hodges’ biography is as follows:

John Hodges trained in medicine and psychiatry in London, Southampton and Oxford before gravitating to neurology and becoming enamoured by neuropsychology. In 1990, he was appointed a University Lecturer in Cambridge and in 1997 became MRC Professor of Behaviour Neurology. A sabbatical in Sydney in 2002 with Glenda Halliday rekindled a love of sea, sun and surf which culminated in a move here in 2007. He has written over 400 papers on aspects of neuropsychology (especially memory and languages) and dementia, plus six books. He is building a multidisciplinary research group focusing on aspects of frontotemporal dementia.

Many posts like this have originally appeared on the blog of the ‘Socialist Health Association’. For a biography of the author (Shibley), please go here.

Many posts like this have originally appeared on the blog of the ‘Socialist Health Association’. For a biography of the author (Shibley), please go here.

Shibley’s CV is here.

"Co-epetition" – how collaborative competition might ultimately benefit the patient

The debate about competition is polar. Either you’re a believer or not.

Yet competition can co-exist with collaboration. Also, in theory, integration or bundling could even be seen as ‘anti-competitive behaviour’.

A trick will be ultimately to find a way in which integration of services cannot offend competition law. As an useful starting point, Curry and Ham (2010) suggest that there are three levels of integration, the top of which is a “a macro-level or systems-level integration”, in which a single organisation or network takes full clinical and fiscal responsibility for the spectrum of health services for a defined population, Underneath is a “meso-level integration of services” for patients with particular conditions, which encompasses a continuum of care for a subset of patients with those conditions.

Ultimately, clinical commissioning groups, whatever expertise they precisely consist of, will need to source services which promote highest quality and best choice for its patients. And yet the law has to reconcile one of its fundamental rules (that everyone is innocent unless otherwise proven guilty), and the law should not penalise people wishing to work together if it is for the benefit of the patient. One is reminded of Diogenes of Sinope (412-323 B.C.) who was seen roaming about Athens with a lantern in broad daylight and looking for an honest man but never finding one.

“Co-epetition” can mean a ‘joint dominance’ of suppliers of health services, provided their activity does not abuse that dominance or distort the market. There are good reasons in business management why certain parties might choose to coordinate their commercial conduct to benefit patients, such as in bundling. Despite certain conflicting interests, they also share strong common values and are exposed to common risks. Such synergies in competences is well known to be essential for building cohesive organisational entities, and in forcing strategic alliances even if there is formal relationship at all.

Unfortunately, joint or collective dominance has been traditionally treated by the Competition Authorities as equivalent to oligopolistic dominance. The concept of joint dominance has been developed under both Article 102 of the Treaty on the functioning of EU. There is some consensus among National Health Service (NHS) researchers, managers and clinical leaders that increased integration within the health system will enable the NHS to respond better to the growing burden of chronic illnesses. In “real markets”, the prohibition laid down in Article 102 TFEU has been justified by the consideration that harm should not be caused to the consumer, either directly or indirectly by undermining the effective competition. However, healthcare is not a “real market”. Unlike the other concepts, co-opetition (blend of cooperation and competition) focuses on both cooperation and competition at the same time.

Basic principles of co-opetitive structures have been described in game theory, a scientific field that received more attention with the book “Theory of Games and Economic Behavior” in 1944 and the works of John Forbes Nash on non-cooperative games. It is also applied in the fields of political science and economics and even universally [works of V. Frank Asaro, J.D.: Universal Co-opetition, 2011, and The Tortoise Shell Code, novel, 2012]. Although several people have been credited with inventing the term co-opetition, including Sam Albert, Microsoft’s John Lauer, and Ray Noorda, Novell’s founder, its principles and practices were fully articulated originally in the 1996 book, “Co-opetition”, by Harvard and Yale business professors, Adam M. Brandenburger and Barry J. Nalebuff.

One sincerely hopes that NHS management will be able to cope with the pace of this debate too. Competitors with such management ability will likely forge a co-opetitive relationship. When two companies compete fiercely in a market, they likely perceive each other as an enemy to defeat, and have less willingness to collaborate, even if they have complementary skills and resources. One day, the best minds in the world will probably ‘have a go’ at producing a coherent construct of this for the NHS quasimarket.

“Co-epetition” provides, furthermore, a mechanism for English health policy to revisit yet again the notion of “public private partnerships” which first probably became really sexy about a decad ago at the heart of the government’s attempts “to revive Britain’s public services”. A decade later, Cameron is still lingering with this particular revival. The problem with how this is sold is that many have rightly rubbished the idea that the private sector is necessarily more “efficient”, an ab initio basic assumption, The private sector, both accidentally and sometimes quite deliberately, introduces needless reduplication and waste, evidenced by the cost of wastage in the US health market. However, the “dream” is that, in trying to bring the public and private sector together, the government hopes that the management skills and financial acumen of the business community will create better value for money for taxpayers.

Globally, diabetes is the second biggest therapeutic “market segment”, behind oncology, in terms of revenues generated. IMS Institute of Healthcare Informatics forecasts that the global diabetic segment will grow to $48-53 billion by 2016. In India, it is already the fastest growing segment. Diabetes medicines currently fall into two broad categories — tablets and injectable insulin. While domestic players are market leaders in the conventional oral drugs segment (market share of 80 per cent), multinational corporations (17 percent) are fast catching up with patent-protected new generation oral drugs. The anti-diabetes market has been consistently growing well above the pharmaceutical market for the past few years. It is possible to see the future in this crowded market in a coupled business strategy that involves in-licensing one or more compounds (new products from multi-national corporations), while continuing with time tested, less expensive (own) products for the mass market.

If the NHS should wish work together with private providers in provision of integrated bundles of healthcare, and the feeling is mutual in a way which clearly promotes patient choice, assuming that all parties see a rôle for the private sector in the NHS, the legislative framework should be re-engineered immediately to reflect that. This should a pivotal task for Monitor to turn its attention to.

Whatever the precise approach taken to “co-epetition”, the current legislative guidance will need to much better defined to ensure that any form of integration does not offend the anti-competitive environment.

The author is extremely grateful for the rich conversations he has had with Dr Na’eem Ahmed who is the first person to the author’s knowledge to acknowledge the potential value of this mode of provider dynamics for the NHS.

Many posts like this have originally appeared on the blog of the ‘Socialist Health Association’. For a biography of the author (Shibley), please go here.

Shibley’s CV is here.

Sustainability: a hopelessly misused word in English health policy, popular for its misleading potential

For Twitter or Google, whose revenue potential is stratospheric, analysts have difficulty in defining how ‘sustainable‘ their business model is.

Turning the NHS into a Darwinian ‘survival of the fittest’ always implied that there were bound to be winners and losers. With recent legal decisions firmly deciding that NHS Foundation Trusts, as “enterprises”, cannot merge on purely economic competition law grounds is a profoundly significant decision, you can certainly say we are living in dangerous times.

And yet ‘sustainability’ is possibly the most misused word in English health policy. It means different things to different people. Its ambiguity means that it is highly popular, particularly for its midleading potential.

I was having dinner with a senior lawyer in Stockwell the other evening, and we both decided that, for many, the word had become synonymous with a meaning of ‘maintained’. We felt this usually led to a discussion of ‘we can’t go like this’, thus softening up the discussion to save money.

There is some method behind this madness, however. Rather than spreading money thinly around various hospitals, possibly there can be fewer hospitals with a ‘safe’ level of resources.

This argument clings onto the idea that the NHS funding is finite, and increasingly ‘unaffordable’. This of course is a perfectly rationale argument if you assume that the Government is incapable of producing economic growth. And for the last three years, the Government has taken us on a turbulent rollercoaster ride of GDP when the UK economy had been recovering in May 2010.

It is currently argued by some that the most successful healthcare organisations are those that can implement and sustain effective improvement initiatives leading to increased quality and patient experience at lower cost. Indeed, the NHS itself has produced a “Sustainability Model and Guide” to support health care leaders to do just that.

Next year, the “NHS Sustainability Day 2014” will feature tools and case studies with proven technologies, methods and projects that have yielded promising results. Technology is often cited as a potential source of the ballooning NHS budget, but the NHS simply has to learn how to order and use technology which is most appropriate for the needs of employees.

So why have the media and other professionals actually lost sight of the actual definition of ‘sustainability’? The politicians have an agenda to make the NHS more ‘affordable’, given the parties en masse wish to embrace ‘savings’ and not be THE parties of high taxation. This, however, means that politicians are being somewhat economical with the truth, and a responsible media here is critical.

Sustainability is the “capacity to endure“. In ecology the word describes how biological systems remain diverse and productive over time. Long-lived and healthy wetlands and forests are examples of sustainable biological systems. For humans, sustainability is the potential for long-term maintenance of well being, which has ecological, economic, political and cultural dimensions. It usually comes from an idea that you look after the people involved, and the environment.

Thee most widely quoted definition of sustainability, as a part of the concept sustainable development, is that of the Brundtland Commission of the United Nations. It was provided on March 20, 1987: “sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

However the neoliberal approach taps into the oft-quoted saying, “The richer get richer; the poor get poorer.” Power always gets in the way of fairness in the game of sharing. With ‘finite resources’, unfortunately there will always be winners and losers. For parties which claim to offer ‘comprehensive, free-at-the-point-of-need’ NHS, clearly it is impossible to square this particular circle.

Irrespective of the ageing population, which is a sensitive argument as it implies that aged individuals are a ‘burden’ on the rest of society despite the value that they have generated over their lifetime, “demand” appears to be fundamentally outstripping “supply”.

According to the 2008 revision of the official United Nations population estimates and projections, the world population is projected to reach 7 billion early in 2012, up from the current 6.9 billion (May 2009), to exceed 9 billion people by 2050.

In 2009, McKinsey says the NHS can save an initial £6bn-£9.2bn a year over the next three years through “technical efficiencies”. This produces a cumulative three year saving close to the £20bn NHS chief executive David Nicholson has been talking about since his annual report in May.

But the McKinsey report went further, suggesting the NHS could save a further £10.7bn a year on top by improving quality and shifting care to the most cost effective settings. Sir David Nicholson, as in effect the NHS’ CEO, grabbed the bull by the horns. Unfortunately, some Foundation Trusts have used ‘efficiency savings’ to run skeleton staff who are always a number of patients ‘behind’ in the Medical Admissions Unit or A&E.

According to a previous report from the National Audit Office, in 2011-12 there was a large gap between the strongest and weakest NHS organisations. The difference was particularly marked in London. At the time, there were 10 NHS trusts, 21 NHS foundation trusts, and three Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) reported a combined deficit of £356 million. The NAO estimated, based on their census of PCTs, that without direct financial support, a further 15 NHS trusts and seven PCTs would have reported deficits.

Sustainability is an issue in the Lewisham case (judgment here). Judge Silber remarked that on occasions it has proven impossible to improve speedily the performance of a failing NHS organisation sufficiently to secure an adequate quality of care for its patients within sustainable resources. For that reason, an exceptional bespoke procedure was introduced to deal with situations which arise,

At paragraph 3, Silber describes it as follows:

“in the words of a senior official of the Department of Health, Dr. Shaleel Kesevan, “where very occasionally it proves impossible to improve the performance of an NHS organisation sufficiently to secure adequate quality of care within sustainable resources”. This regime is entitled the “Unsustainable Providers Regime” (“the UPR”), which as its name shows was intended to deal with failing NHS organisations.”

It is clear then that some of the basic, actual, definition of ‘sustainability’ has got lost in translation. This is unfortunate given that the primary purpose of politicians, of all shades, should not to be to mislead the general public whether intentionally or unintentionally.

Above all, the NHS should be in touch with its wider environment. This does mean that the NHS should look to the forests or trees for inspirations. It means that when 50,000 protest lawfully in Manchester, there is no news blackout and people are genuinely concerned about why people are so upset.

It means listening to local residents in Lewisham. It does not mean instinctively using hardworking taxpayers’ money to appeal against a decision from the High Court in the Court of Appeal.

It also means listening to the views of nurses when they’re in a job, and listening meaningfully to them if you need to sack them. It is not as if the NHS is actually short of work to do, which is why some find it objectionable that there are staff cuts with ever-increasing demand.

That is the true meaning of ‘sustainable’. Unfortunately, the current Government is producing amendments to the insolvency regime to make neoliberal closures easier for the State, quicker than you can say, “Earl Howe”.

The NHS might be truly ‘sustainable’ if you pay especial attention to hardworking hedgies, as per the Royal Mail privatisation. To take the neoliberalisation of the NHS to the limit, you could sell it off as an initial public offering (or flotation). But is this another difficult choice the public are being shielded from?

The word “sustainable” has been bastardised. It has been taken away from its true meaning from the macroeconomics. Such abuse of language is symptomatic of an abuse of political power.

Many posts like this have originally appeared on the blog of the ‘Socialist Health Association’. For a biography of the author (Shibley), please go here.

Shibley’s CV is here.

The future of general practice in England

One of the most striking aspects of the biggest reorganisation in the history of the NHS in recent years, estimated to cost about £3bn, is that it manifests glaring gaps in legislation. There is not a single clause on patient safety, save for abolishing the National Patient Safety Agency. It also does not discuss general practitioners themselves. It does contain a nice legislative framework however for the law anticipated for scenarios (sic) quite close to asset stripping, in the event that NHS Trusts have to be wound up due to insufficient funds.

I took a relative to have her ear syringed this morning in a local general practice, and I was thinking only this morning how general practice would be likely to have a backdoor reconfiguration in the next parliament whoever is in power.

I personally am fed up of even hearing about, let alone discussing, the “Tony Blair Dictum”. I prefer to think of it now as “The Deceptive London Cab Analogy“. The Dictum in its various manifestations states that it doesn’t matter who provides my NHS services, as long as it’s of good quality and free at the point of use et cetera. I have always found the idea of private providers freeloading on the goodwill and reputation of the NHS as odd, when presumably they wish to establish the quality and kudos of their own distinctive services. I think the “Deceptive London Cab Analogy”, in that I don’t particularly care if it is actually a London cab, as long as it looks like a London Cab, and gets me from A to B (for example the Royal College of Surgeons in Lincoln’s Inn Fields to the Royal College of Physicians in St Andrew’s Place). It’s a bonus actually if it costs me less. I don’t care how it gets me there; in effect, there’s no difference between using a SatNav or somebody who has done 4 years of “The Knowledge” and has been examined accordingly.

Primary care is of course “the elephant” in the room, in that everyone knows that certain multi-nationals, assisted by liberalisation of international free trade, are licking their lips. It’s yet another one of those unmentioned topics in policy, like the NHS McKinsey efficiency or productivity savings, co-payments or personal health budgets. The whole world knows the existence of policy forks in the world, except none of the established traditional parties wish to discuss precisely the details. And people within thinktanks can continue to spin their motherhood and apple pie, in the hope that they can curry favour with an incoming administration. But it’s important for us who have other views on this to make such views known clear, otherwise a political party, including Labour, could legislate through the backdoor based on conversations also done behind-the-scenes. The public, whilst fed up about this ‘democratic deficit‘, are relatively powerless over it.

In 2010, Apax Partners published a revealing document entitled, “Opportunities: Post Global Healthcare Reforms“. The Apax Partners Global Healthcare Conference, which took place in New York in October 2010, sought opinions about the future of healthcare from some interested stakeholders. The ideology of the document is clear:

“With over 1.3 million employees, the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) is the world’s fourth largest employer and one of the most monolithic state providers of healthcare services.”

It is the ultimate nirvana for a businessman to find a new market. And general practice is articulated in those terms in the Apax document:

“The other change that (Mark) Britnell sees in the UK is even more fundamental: “In future, The NHS will be a state insurance provider not a state deliverer.”

Mark Britnell has been previously mooted as a possible contender for the replacement of Sir David Nicholson in the Health Services Journal.

The main problem about the current NHS top-down reorganisation is that it is important to identify the correct problem before producing an appropriate solution. If the problem which the Government wished to address was how to outsource and increase the number of private providers in the NHS, the solution, if implemented successfully, can be considered to be appropriate. When McKinsey sneezes, English health policy catches a cold. In this regard, McKinsey’s document, entitled “Five strategies for improving primary care” (“Report”; to download, please follow this link) provides some useful pointers. Affirming the importance of this market, the authors (Elisabeth Hansson and Sorcha McKenna) begin with the statement, “Primary care is pivotal to any health system.” Indeed, the first identified problem is that ‘in many countries, patients are dissatisfied with their ability to see GPs in a timely fashion.’ This is of course a problem which the operations management of any State-run service can address too. It is reported that, in Sweden, for example, many patients report that they cannot get timely access to their GP, especially by telephone. This is conceivably something which patient groups or the Royal College of General Practitioners could collect data on (and there is no shortage of data collection in primary care in the name of QOF) to improve the quality of the service.

It is mooted that, “the productivity of British GPs, for example, has dropped sharply in the past 15 years despite the fact that the government has markedly increased what it pays them“, on page 71, but this will be strongly contested by British GPs one assumes. The Report specifically discusses QOF thus:

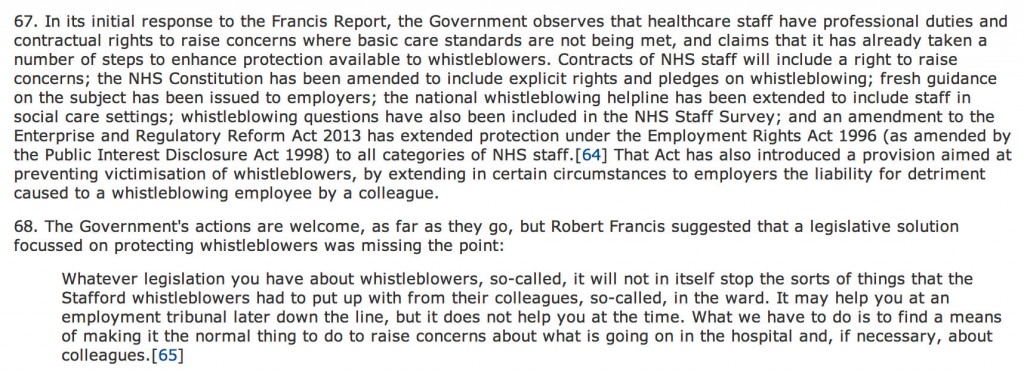

“The United Kingdom has attempted to improve the quality of its primary care services through a new program, the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), which gives GPs additional payments if they meet specified outcome metrics (for instance, the percentage of hypertensive patients whose blood pressure is lowered to the normal range). The program has been successful in focusing attention and improving scores on those metrics, but it has become clear that a GP’s performance on those metrics does not always reflect the overall quality of his or her practice.”

There has been, particularly since Kenneth Clarke’s “The Health of the Nation” paper in the 1980s, an enthusiasm for GPs to be paid to collect data, but such data has to be meaningful.

Consistent with the Health and Social Care Act (2012), and the pivotal section 75 which acted as the rocket boosters for introducing competitive tendering formally into the English NHS, the document argues that:

“In both tax-based and insurance-based systems, competition is a way to increase GP productivity and the quality of care, because it signals to physicians that they will have to perform better if they want to retain their contracts and patients.”

This has only this week been powerfully rebutted by Professor Amanda Howe (MA Med MD FRCGP), Honorary Secretary of Council the Royal College of General Practitioners, in her response to Monitor as a member of Council (as linked here):

“The RCGP welcomes Monitor’s stated aim to better understand the challenges faced by general practice at a time when it is operating under increased pressure. However, we would strongly caution against the assumption that the challenges faced by general practice are caused by a lack of competition, or that the best lever to reduce perceived variability in access and/or quality would be an increase in competition.”

One of the most powerful levers described by the Report is “changing the operating model”.

“This lever is conceptually simple but often difficult to implement. For example, it often makes a great deal of sense to move physicians away from small (often solo) practices and into larger primary care practices or polyclinics (which include a wider variety of services, including diagnostics and outpatient clinics). Larger practices and polyclinics allow physicians to achieve economies of scale in some areas, such as administration. Furthermore, having a mix of physicians working together can improve quality and provide a more attractive working environment for new physicians (which might then help increase the workforce supply).

If a health system does decide to change its primary care operating model, it should consider a question even more radical than where physicians should work—it should ask whether certain primary care services need to be delivered by physicians at all. In the United States, for example, certain nurses with advanced training (nurse practitioners) are legally able to perform physical examinations, take patient histories, prescribe drugs, and administer many other basic treatments. Nurse practitioners can usually provide these services at a much lower rate than physicians typically can, but with comparable quality.”

This is a powerful summary, as it is consistent with the view that certain jobs can be better done by cheaper workforce. This is i itself a constructive idea potentially, simply in organising functions within the workforce for the people most suitable to deliver those functions. For example, many NHS hospitals have employed “physician assistants” to put in venflons or insert catheters, freeing up junior doctors to get on with other tasks in their busy schedule too. There comes a problem as to whether diagnostic services should be ‘liberalised’ on demand, i.e. so that the ‘worried well’ establishing their autonomy can pay to have their blood pressure checked ‘on demand’ if they want it. Provided that the equipment works, and the user of the diagnostic equipment does not use that equipment negligently, and that the investigation itself did not do any harm or damage, a regulator might not intervene, depending on the exact circumstances of course.

The second “big lever” is integration, described as follows:

“As we discussed earlier, GPs are typically responsible for coordinating with all the other health professionals and organizations (sic) that provide care for a patient. Coordination is hampered, however, by the fact that few health systems have effective methods for ensuring that information is transmitted to the appropriate places. Ensuring that such communication takes place does not require that all providers be part of a single organization (sic). However, it does require that all providers commit to sharing information and coordinating care and that a strong IT system operating on a joint platform is available to facilitate data exchange. Payors can encourage this type of alignment through their contracting (for instance, by requiring the providers to report the same set of metrics).”

And there is still a hangover of the integrated healthcare model from the US health maintenance organisations. Here it is possibly more of a case of joined-up thinking in some different ways. Regulators should be mindful of referrals being made between primary care and secondary care (where VerCo GP practice refers to Verco NHS Trust) not on the basis of clinical need but for shareholder dividend, though the cases of clinical regulators making sanctions on the basis of unethical conflicts of interest are currently sparse for whatever reasoning. It is also remarkable how keen and enthusiastic many corporates are on building the IT infrastructure for primary care, and indeed these noises of data sharing and paperless records are echoed by Jeremy Hunt. Ultimately, if one so wishes, whoever ‘owns’ primary care, whether it is a state-run service or not, this IT system could be ultimately linked to the private insurance system; a minority feel that that is where an aspect of integrated care is ultimately aiming towards.

The drumbeat from McKinsey’s and Apax is therefore providing a structural set-up and culture such that there can be a greater number of private providers in the holy grail of primary care. The notion that GPs are ‘only interested in their wallet’ (as famously said by Kenneth Clarke) is not at all borne out by the evidence from the professional bodies or regulators, and whilst there have been many touting GPs as businessmen (including some isolated opinions from the leadership of the Socialist Health Association (“SHA”) which have to be read in context, e.g. as in this recent blogpost by Martin Rathfelder (Director of the SHA)):

“The issue is blurred anyway as many GPs have found ways to “profit” through taking interests in companies providing services.”

People who do not hold the same views as McKinseys’ and Apax should be allowed to influence an incoming Labour government, whether they are or have been the leadership of the SHA or not. It is hoped that these alternative views do not merely act as a boring echochamber, and genuinely reflect the founding values of the NHS.

Many posts like this have originally appeared on the blog of the ‘Socialist Health Association’. For a biography of the author (Shibley), please go here.

Shibley’s CV is here.

What's best for a person isn't necessarily what's best for a hospital

It is pretty clear that the NHS as currently engineered puts Foundation Trusts on an elevated platform. Hospitals, being paid on the basis of activity involved for any one patient, can act for a sink for funding, when the health of any particular person is not easily matched to the aggregate level of activity for that person in a hospital.

The problem with ‘money following the patient‘ is it depends on whether you view it to be a success or failure that more money is spent on you the more ill you become. When a patient is admitted for an acute medical emergency in England, the care pathway can be pretty unambiguous. Most reasonable doctors on hearing about a history of cough, sputum and temperature, for a person with new breathing difficulties, on seeing the appropriate chest x-ray, would embark on a management of pneumonia; depending on the hospital, the course of antibiotics would be pretty standard from i.v. to oral, and the person would end up being discharged.

However, ‘activity based costing‘ and ‘payment by results‘ for hospital totally ignore the health of a person outside hospital. And if a healthcare model is to shift with time to ‘whole person care‘, what happens to a person outside of hospital is going to become increasingly important. If a person is better ‘controlled‘ for diabetes in the community, it is hoped that emergency admissions, such as for the diabetic ketocacidotic coma, can be avoided; or for example if a person is able to monitor their breathing peak flow in the community and notice the warning signs (such as a change in the colour of sputum), an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may be headed off at the pass.

Medicine is not an exact art or science, and the approach of ‘payment-by-results’, of a managerial accounting approach of activity-based costing, is at total odds to how decisions are actually made. Even in complex economics, within the last decade or so, the idea of “bounded rationality” has conceded that in decision-making, rationality of individuals is limited by the information they have, the cognitive limitations of their minds, and the finite amount of time they have to make a decision. Many ‘decision makers’ are not in fact perfectly rational, and it is likely that even the best doctors will differ in exact details for management of a patient in hospital for any given set of circumstances.

In health care, value is defined as the patient health outcomes achieved per pound spent. Value should be the pre-eminent goal in the health care system, because it is what ultimately matters for patients. Value encompasses many of the other goals already embraced in health care, such as quality, safety, patient centeredness, and cost containment, and integrates them.

However, despite the overarching significance of value in health care, it has not been the central focus.

The failures to adopt value as the central goal in health care and to measure value are arguably the most serious failures of the medical community.

Health care delivery involves numerous organisational units, ranging from hospitals, to departments and divisions, to physicians’ practices, to units providing single services. The fundamental failing has been not to acknowledge how all these units interact in the “patient journey”.

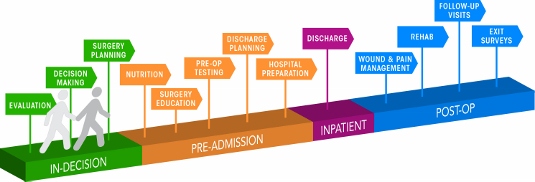

Patient journey for a surgical operation

Patient journey for a surgical operation

In health care, needs for specialty care are determined by the patient’s medical condition. A medical condition is an interrelated set of patient medical circumstances — such as breast cancer, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, or congestive heart failure — that is best addressed in an integrated way. Therefore, a patient can be ‘plugged into the system’, as Mr X attending the specialist cystic fibrosis clinic at a local hospital. However, it is equally true to say that there are many patients with many different conditions, which interact either in disease process or treatment. And there are people who may later develop a medical illness who are perfectly well at any one ti,e.

For primary and preventive care, value could be measured for defined patient groups with similar needs. Patient populations requiring different bundles of primary and preventive care services might include, for example, healthy children, healthy adults, patients with a single chronic disease, frail elderly people, and patients with multiple chronic conditions. Each patient group has unique needs and requires inherently different primary care services which are best delivered by different teams, and potentially in different settings and facilities. However, life is clearly not so simple, and the beauty about the National Health Service is that it does not consider a person as the sum of his individual insurance packages.

Care for a medical condition (or a patient population) usually involves multiple specialties and numerous interventions. The most important thing here is that value for the patient is created not by any one particular intervention or specialty, but by the combined efforts of all of them. (he specialties involved in care for a medical condition may vary among patient populations. Rather than “focused factories” concentrating on narrow sets of interventions, we need integrated practice units accountable for the total care for a medical condition and its complications. To give as an example, optimal glucose control for diabetes in the community could possibly mean fewer referrals to the specialist eye clinic for the condition of diabetic retinopathy, an eye manifestation of diabetes, or to the vascular surgeon for a gangrenous toe requiring amputation.

A major barrier to delivering this care will be a fragmented, outsourced or privatised, NHS. In care for a medical condition, then, value for the patient is created by providers’ combined efforts over the full cycle of care — not at any one point in time or in a short episode of care. The only way to accurately measure value, then, is to track individual patient outcomes and costs longitudinally over the full care cycle. And this will be difficult the more care providers there are for any one patient.

Although outcomes and costs should be measured for the care of each medical condition or primary care patient population, current organisational structure and information systems make it challenging to measure (and deliver) value. Thus, most providers fail to do so. Providers tend to measure only the portion of an intervention or care cycle that they directly control or what is easily measured, rather than what matters for outcomes. For example, current measures often cover a single department (too narrow to be relevant to patients) or outcomes for a hospital as a whole, such as infection rates (too broad to be relevant to patients). Or providers measure what is billed, even though current reimbursement is for individual services or short episodes.

A way to get round this problem is to consider “indicators” which are are biological measures in patients that are predictors of outcomes, such as glycated hemoglobin levels (“HBA1c”) measuring blood-sugar control in patients with diabetes. Indicators can be highly correlated with actual outcomes over time, such as the incidence of acute episodes and complications. A HbA1c can be a good indicator of the compliance of an individual with diabetes with his or her medication or diet.

Indicators also have the advantage of being measurable earlier and potentially more easily than actual outcomes, which may be revealed only over time.

This is where over-focus on the wrong measure can be unhelpful. The launch of the ‘friends and family test’, which has seen an explosion of innovative technologies being sold to NHS Foundation Trusts over all the land, may be an important means of ensuring patient safety. Or it may not. We don’t know, as the data on this doesn’t exist.

However, patient satisfaction has multiple meanings in value measurement, with greatly different significance for value. It can refer to satisfaction with care processes. This is the focus of most patient surveys, which cover hospitality, amenities, friendliness, and other aspects of the service experience. Though the service experience can be important to good outcomes, it is not itself a health outcome. The risk of such an approach is that focusing measurement solely on friendliness, convenience, and amenities, rather than outcomes, can distract providers and patients from value improvement.

Value measurement in health care today in the English NHS is rather limited, and highly imperfect. Most physicians lack critical information such as their own rates of hospital readmissions, or data on when their patients returned to work. Not only is outcome data lacking, but understanding of the true costs of care is virtually absent. Most physicians do not know the full costs of caring for their patients — the information needed for real efficiency improvement.

In the recent target-driven culture of the English NHS, senior physicians are well aware of how length-of-stay has been gamed so there has been a ‘quick in and quick out’ mentality, seeing readmission rates for certain patients with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease sky-high.

At worst, what could have been a properly managed non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome ultimately ends up being a full-blown heart attack. Or what could have been a minor transient ischaemic attack ends up being a full-blown haemorrhagic stroke, causing a patient to be in a wheelchair and numerous healthcare teams looking after him or her.

Today, measurement focuses overwhelmingly on care processes. Processes are sometimes confused or confounded not only with outcomes, but with structural measures as well. Radiologists focus on the accuracy of reading a scan, for example, rather than whether the scan contributed to better outcomes or efficiency in subsequent care. Cancer specialists are trained to focus solely on survival rates, overlooking crucial functional measures in which major improvements vital to the patient are possible.

Cost is among the most pressing issues in health care, and serious efforts to control costs have been under way for decades. At one level, there are endless cost data at all levels of the system. However, as an ongoing project with Robert Kaplan makes clear, we actually know very little about cost from the perspective of examining the value delivered for patients.

Understanding of cost in health care delivery suffers from two major problems. The first is a cost-aggregation problem. Today, health care organisations measure and accumulate costs for departments, physician specialties, discrete service areas, and line items (e.g. supplies or drugs). As with outcome measurement, this practice reflects the way that care delivery is currently organised and billed for. Today each unit or department is typically seen as a separate revenue or cost centre. Proper cost measurement is challenging because of the fragmentation of entities involved in care.

To understand costs properly, they must be aggregated around the patient rather than for discrete services, just as is the case with outcomes. It is the total costs of providing care for the patient’s medical condition (or bundle of primary and preventive care services), not the cost of any individual service or intervention, that matters for value. If all the costs involved in a patient’s care for a medical condition — inpatient, outpatient, rehabilitation, physiotherapy, dietician, occupational therapy, diagnostic services, pharmacy, physician services, equipment, facilities — are brought together, it is then finally possible to compare the costs with the outcomes achieved.

Proper cost aggregation around the patient will allow us to distinguish charges and costs, understand the components of cost, and reveal the sources of cost differences.

Today, most physicians and provider organisations do not even know the total cost of caring for a particular patient or group of patients over the full cycle of care. There has been no reason to know, and Doctors resent turning their profession of medicine into one of bean-counting.

In aggregating costs around patients and medical conditions, we quickly arrive at the second problem: “the cost-allocation problem“. Many, even most, of the costs of health care delivery are shared costs, involving shared resources such as physicians, staff, facilities, equipment, and overhead functions involved in care for multiple patients. Even costs that are directly attributable to a patient, such as drugs or supplies, often involve shared resources, such as units involved in inventory management, handling, and set-up (e.g., the pharmacy). Today, these costs are normally calculated as the average cost over all patients for an intervention or department, such as an hourly charge for the operating room. However, individual patients with different conditions and circumstances can utilize the capacity of such shared resources quite differently.

The NHS in England has latterly become obsessed by its “funding gap”. Much health care is delivered in over-resourced facilities. Routine care, for example, is delivered in expensive hospital settings. Expensive space and equipment is underutilised, because facilities are often idle and much equipment is present but rarely used. Skilled physicians and staff spend much of their time on activities that do not make good use of their expertise and training. It is not uncommon for junior doctors to end up spending hours in a hospital taking blood, putting in catheters, or putting in venflons.

It is likely that ‘payment-by-results’ will at some stage have to go. Reimbursement should cover a period that matches the care cycle. For chronic conditions, bundled payments should cover total care for extended periods of a year or more. Aligning reimbursement with value in this way rewards providers for efficiency in achieving good outcomes while creating accountability for substandard care.

Improvements in outcomes and cost measurement will greatly ease the shift to bundled reimbursement and produce a major benefit in terms of value improvement. Current organisational structures, practice standards, and reimbursement create obstacles to value measurement, but there are promising efforts under way to overcome them.

The “payment-by-results” model is a complete anethema to how decisions are made in the real world. Prospect theory is a behavioral economic theory that describes the way people choose between probabilistic alternatives that involve risk, where the probabilities of outcomes are known. The theory states that people make decisions based on the potential value of losses and gains rather than the final outcome, and that people evaluate these losses and gains using certain heuristics. The model is descriptive: it tries to model real-life choices, rather than optimal decisions. The theory was developed by Daniel Kahneman, a professor at Princeton University’s Department of Psychology, who won the Nobel Prize for economics in 2002.

It is a pity that the payment-by-results ideology has been so overwhelming, perhaps powerfully pushed for by the accountants and management consultants wishing to drive ‘efficiency’ in the NHS, taking the media with them on this escapade. However, it is poorly aligned to how healthcare, psychiatric care and social care professionals make decisions in the real world.

Critics will correctly argue that value is notoriously difficult to measure, and might be virtually impossible to measure across a ‘care cycle’. Indeed the original criticism of the Kaplan and Cooper (1992) account of ‘activity based costing’ warned against organisations allocating excessive resources to collecting information which they are then able to make use of properly.

We are quickly coming to an age where it is going to be a ‘good outcome’ to keep a frail patient out of hospital through high quality care in the community through integrated teams. By that stage, the ideological shift from cost to value will have needed to have taken place, and funding models will have to reflect more the drive towards value and ultimate clinical outcome.

Many posts like this have originally appeared on the blog of the ‘Socialist Health Association’. For a biography of the author (Shibley), please go here.

Shibley’s CV is here.

Should Doctors and Nurses act as surrogate immigration officials?

Anyone can get very ill at any time.

This issue is also about recognising mutual obligations and responsibilities, and looking after all our futures.

Would you like to be a British citizen abroad in France and being refused treatment?

Nonetheless, the British media has been relentless in presenting the ‘dogwhistle’ politics of immigration, rather than having an open, honest or complete debate about the NHS privatisation enacted by this Government.

Jeremy Hunt MP says today:

Having a universal health service free at the point of use rightly makes us the envy of the world, but we must make sure the system is fair to the hardworking British taxpayers who fund it.

This current Government, it has been argued, has been extremely divisive, setting off able-bodied people against disabled citizens, employed people against unemployed, and so it goes on.

The ludicrous farce of this latest announcement, of cracking down on “health tourism”, is that similar announcements have been made before. In the meantime, Hunt has been forced to apologise for a tweet when faced with legal action, and there has been talk of an impending crisis in acute medicine.

Today’s announcement will again see Ministers facing renewed claims that GP surgeries are being turned into “border posts”.

In its three years in power the government has a poor record on announcing policies that sound good but prove to be completely unworkable

(shadow health minister Liz Kendall, previously)

The Chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners, Prof Clare Gerada, has previously warned that:

“GPs must not be a new ‘border agency’ in policing access to the NHS. While the health system must not be abused and we must bring an end to health tourism, it is important that we do not overestimate the problem and that GPs are not placed in the invidious position of being the new border agency.”

Today, the Department of Health is publishing the first comprehensive study of how widely migrants use the NHS. These independent findings show the major financial costs and disruption for staff which result from a system which will be substantially reformed in the interests of British taxpayers. Just because they are ‘independent’ findings does not necessarily mean they are very accurate, as any observer of the “output” of the OBR will tell you.

Previous estimates of the cost to the NHS have varied, but this latest attempt research reveals the cost may be significantly higher than all earlier figures.

To tackle this issue and deter abuse of the system, the #omnishambles Government is proposing the following now:-

- introducing a simpler registration process to help identify earlier those patients who should be charged.

- looking at new incentives so that hospitals report that they have treated someone from the EEA to enable the Government to recover the costs of care from their home country.

- introducing a new health surcharge in the Immigration Bill to generate income for the Government (but it is unlikely this money will go into frontline patient care, as indeed the £2.4bn “efficiency savings” have not been returned either);

- appointing Sir Keith Pearson as an independent adviser on visitor and migrant cost recovery;

- identifying a more efficient system of claiming back costs by establishing “a cost recovery unit”, headed by a Director of Cost Recovery;

Andy Burnham MP, Labour’s Shadow Health Secretary, responding to Jeremy Hunt’s announcement on overseas visitors’ and migrants’ use of the NHS, said:

We are in favour of improving the recovery of costs from people with no entitlement to NHS treatment. But it’s hard not to conclude that this announcement is more about spin than substance. The Government’s own report undermines their headline-grabbing figures, admitting they are based on old and incomplete data. Instead of grand-standing, the Government need to focus on delivering practical changes. Labour would not support changes that make doctors and nurses surrogate immigration officials.

For a video of Andy Burnham MP responding to this latest report, please go here.

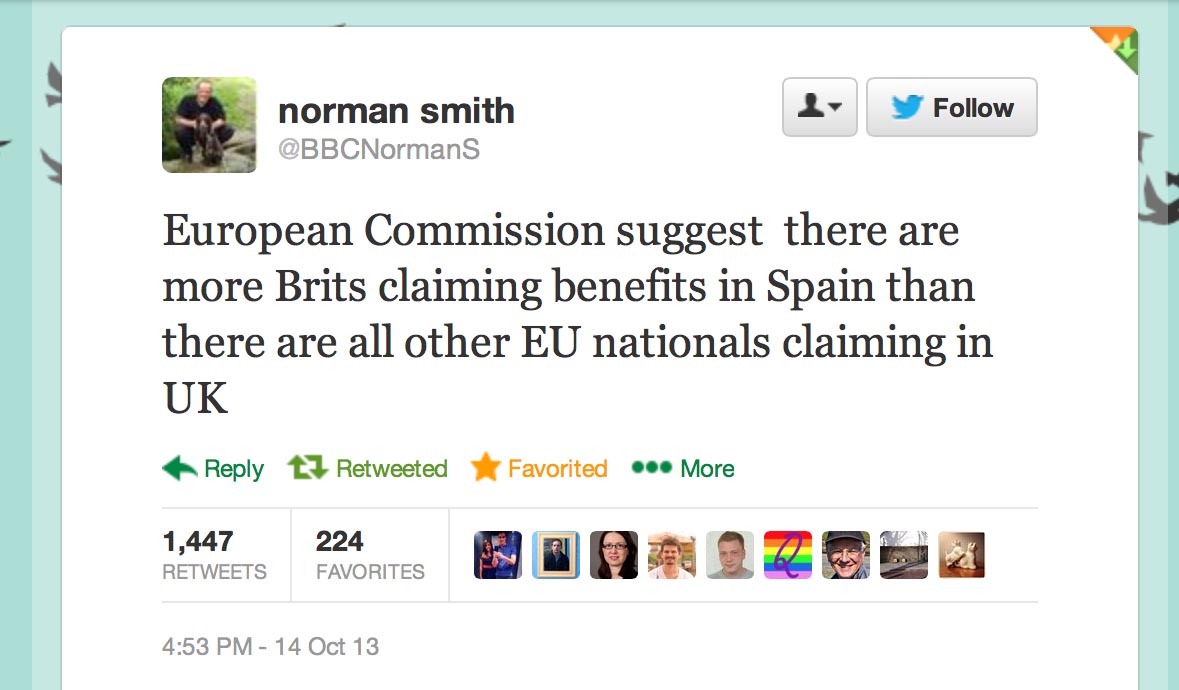

Furthermore, it appears that what Hunt won’t say about migrants is that British expatriates might make much heavier use of the NHS than any other visitors (and accordingly they should pay.)

A recent report by the European Commission concluded that so-called benefits tourism was “neither widespread nor systematic”.

As for most countries, residency not nationality primarily determines eligibility for healthcare treatment.

With the Conservative Party finding themselves ‘squeezed’ by UKIP in the run-up to the European elections, this could provide an useful smokescreen for the disaster in acute care which the Conservatives have somehow single-handedly generated.

However, the “benefits tourism” narrative of the Conservatives and UKIP was dealt a heavy blow by the emergence of this information, which the BBC’s Norman Smith tweeted earlier last week:

Last week’s announcement by Jeremy Hunt on loneliness was panned in a widespread manner by many professionals.

Maybe for the Conservatives there is ‘no such thing as Society’ after all?

Overseas visitors and migrant use of the NHS: extent and costs

Many posts like this have originally appeared on the blog of the ‘Socialist Health Association’. For a biography of the author (Shibley), please go here.

Shibley’s CV is here.

Simon Stevens. Is it not where you've come from, but where you're going to?

The new NHS England Chief Executive is Simon Stevens.

Hailed as a ‘great reformer’, the first accusation for Simon Stevens is that he has been parachuted in to change the culture of the NHS. For all the recognition of patient leaders and home-grown leaders in the NHS Leadership Academy, it is striking that NHS England has made an appointment not only from outside the NHS but also from a huge US corporate. Indeed, Christina McAnea, head of health at the union Unison, told the Today programme on BBC Radio 4: “I am surprised that they haven’t been able to find someone within the NHS.”

A person like Stevens is likely to bring a breadth of managerial experiences, although he has never done a hospital job. He is no expert in land economy either. Despite the drama, the transition of the NHS to a neoliberal one has been on a fairly consistent course, as I explained previously in a now quite famous blogpost. I have also discussed how competition was introduced as a major plank in the Health and Social Care Act (2012) despite the overwhelming evidence against its implementation, known at the time; and how the section 75 and associated regulations would be the mechanism to achieve the ‘final blow’ for liberalising the NHS market. Where possibly English health policy experts have failed, perhaps, in their overestimation of the predeterminism that has taken place in England’s health policy since 1997. Changes of government have brought with it various changes in emphasis, such as the Blairite need to ‘reform public services’, possibly away from a socialist centre of gravity. The changing health policy has also had to take on board changes in politics, economics and legal considerations in the last few decades.

The suggestion that NHS England could have chosen ‘a more socialist CEO’ in itself is fraught with criticisms. Can you ‘a bit’ socialist or ‘half socialist’? Indeed, can you implement a ‘socialist NHS’ without implemented a sharing of resources across various sectors, including education or housing? People who don’t wish to engage with such arguments often end up with extremist Aunt Sally arguments referring to socialism as a state like pregnancy or like a religion, but the ideological question still remains can you have state provision of the NHS on a sliding scale from 0-99% private provision? With the current debate about whether Labour would renationalise the railways, in light of the fact that monies are potentially found out of nowhere for foreign military strikes at the drop of a hat, this discussion has never been more relevant potentially. One of David Cameron’s famous phrases, somewhat ironic given his background at Eton and Oxford, is, apparently: “It’s not where you’ve come from – it’s where you’re going to.” This may apply to not only Stevens but the whole of NHS England, especially if you hold the alternative viewpoint that the NHS could and/or should jettison its ‘founding principles’.

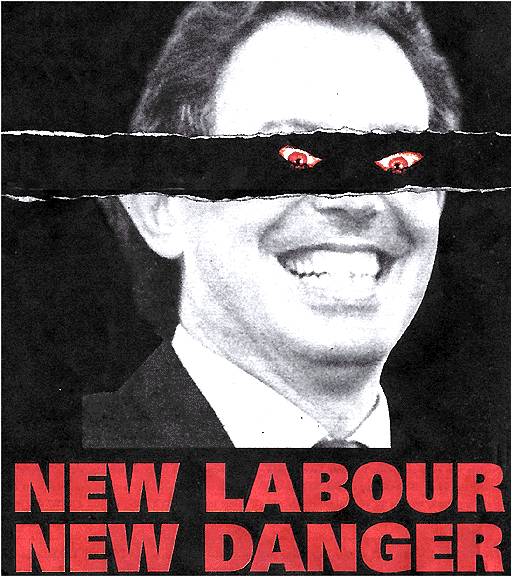

It is all very easy to play the ‘man’ not the ‘ball’, and certainly NHS England already has its strategic goals. Nonetheless, it is critically important for any organisation, particularly the NHS, to think about how much of its strategic aims have to be driven from the very top. Attention has turned to the US company he has spent the last decade with as a senior executive: United HealthCare. There is no point, however, being necessarily alarmist. Pro-NHS campaigners will be mindful of this now largely discredited campaign. Resorting to such emotive messaging may distort the genuine discussion which needs to be had about the future of the NHS in England.

Mr Stevens, 47, was Tony Blair’s health advisor between 2001 and 2004, and before that advisor to then-health secretary Alan Milburn. Simon Stevens’ CV reveals that he was a Trustee from The Kings Fund, London (a health charity) between 2007 – 2011 after being a Councillor for Brixton, south London London Borough of Lambeth 1998 – 2002 (4 years). It has even been alleged that Stevens has been a member of the Socialist Health Association. The NHS budget has been notionally protected – it is rising 0.1% each year at the moment – the settlement still represents the biggest squeeze on its funding in its history. Labour has criticised previously how the Coalition has misrepresented the current state of NHS spending. The currently chief executive of the English NHS, David Nicholson, recently called for politicians to be “completely transparent about the consequences of the financial settlements” for the NHS. Nicholson’s point perhaps was that, although politicians say the NHS has been protected financially, this was only relative to real cuts in other areas of government and, crucially, not in terms of the demands on healthcare.

A clue as to how Mr Stevens will run the NHS could be seen earlier this year when he co-authored a report for UHC arguing that the Obama administration could save $500bn in Medicare and Medicaid funding over the next 10 years by more aggressively coordinating medical care for pensioners and the poor. This pitch will have been very attractive to Sir Malcolm Grant. Mr Stevens said instead of concentrating on either cutting benefits or cuts to doctors and hospitals, the US healthcare debate should focus on a “third way”: cutting costs while improving care. A similar challenge awaits him at the NHS. However, the Keogh mortality report identified that safe staffing was a pivotal reason why NHS Trusts had failed un basic patient safety. Stevens is definitely unlikely to find a “third way” between balancing budgets to provide unsafe clinical staffing levels and adequate patient safety.

Some ministers have repeatedly praised Blair’s attempts to reform services, in the earlier period of their administration. In a speech to the Tory party conference earlier this month, Jeremy Hunt highlighted the efforts of Mr Blair and Mr Milburn to increase the use of the independent sector to reduce waiting times. However, Mr Stevens is also associated with the introduction of NHS targets, and helped create the key plan which brought them in. This NHS “target culture” which have been repeatedly attacked by the Coalition as playing a part in scandals such as that at Mid-Staffordshire, as a root cause of the ‘bully boy’ tactics (allegedly) by some NHS CEOs to achieve Foundation Trust and receive personal bonuses. Particularly important then for Labour is not where it has come from but where it is going to.

Andy Burnham MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Health, has repeatedly stated that a Labour Government will repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012) in its first Queen’s Speech in 2015. It has also been made clear that Labour will do this, even if Burnham is recruited laterally to a different job. For any corporate strategy, a number of drivers will be essential to remember: for example environment, socio-cultural, technological, legal and economics. With the appointment of Stevens “just in time” for the privateers – quite possibly, it is still remarkable that working out the legal niceties of working out ‘mission creep’ in the special administrator powers of NHS configurations is ‘work in progress’. Only this week, it was reported that the Royal Colleges of Physicians have genuine concerns about whether other amendments to the Care Bill are in the patients’ interest, pursuant to the current high-profile mess in Lewisham. Both Stevens and Grant are fully aware that they will have to deal with the political landscape, whatever that is, on May 8th 2015 and afterwards.

Strategic demands of the NHS

Currently NHS England has a number of powerful strategic demands, which could even appear at first blush inherently contradictory. For example, a purpose of patient safety management will be to minimise risk of harm to patients, whereas successful promotion of innovation can be achieved through encouraging risk taking in idea creation. Whatever Stevens’ ultimate vision – and this is why the implementation of Health and Social Care Act (2012) has been so cack-handed – it is essential that industry-acknowledged frameworks for change management are considered at the least. For example, in Kotler’s model of change management, the leader (Stevens) will not only have to ‘create a powerful vision’ but ‘communicate the vision well’.

Patient safety

There is no doubt that the Mid Staffs scandal was a very low point in the NHS. But there’s nothing like a good scandal for focusing the mind? In a general article in June 2009 by James O’Toole and Warren Bennis in the Harvard Business Review (“HBR”), the authors that no organisation could be honest with the public if it’s not honest with itself. This simple principle has been slow to come into the English law, though it has been introduced as an amendment in the Care Bill (2013). A notion has arisen that members of senior management turn a blind eye to failings deliberately (“wilful blindness“), but interestingly the authors draw on the work on Malcolm Gladwell. In his recent book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell had reviewed data from numerous airline accidents. Gladwell remarks, “The kinds of errors that cause plane crashes are invariably errors of teamwork and communication. One pilot knows something important and somehow doesn’t tell the other pilot.” The question is, necessarily, what a CEO can do about it. The authors propose two solutions inter alia. One is to “reward contrarians”, arguing that an organisation won’t innovate successfully if assumptions aren’t challenged. The authors advise organisations, to promote a ‘duty of candour’, to find colleagues who can help, who can be promoted, and who can be publicly thanked. The authors also advise finding some protection for whistleblowers: this might even include people because they created a culture of candour elsewhere. Initiatives such as the Nursing Times ‘Speak Out Safely’ are likely to be highly influential in catalysing a change, but a lot depends on the legal protection for whistleblowers given the current perceived inadequacies of the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998.

There is a growing realisation of implementation of patient initiatives has to be ‘top down’ as well as ‘bottom up’. For example, for Diane Cecchettini, president and CEO of MultiCare Health System, Tacoma, Washington, the key to patient safety has been achieved through leader engagement. She has developed an over-arching strategic framework for quality and safety that has served as the catalyst for the development of multi-year strategic quality and safety improvement plans throughout the MultiCare Health organisation.

Innovation

Innovation is another thorny subject. Innovation (and integration) is always going to be on a dangerous path if primarily introduced as an essential ‘cost cutting measure’, rather than bringing genuine value to the healthcare pathways. Nonetheless, the issue of financial sustainability of NHS England is a necessary consideration, even if the term ‘sustainability’ is open to abuse as I argued previously.

Innovation means different things to different people. As there is no single authoritative definition for innovation and its underlying concepts, including the management of innovation, any discussion on the topic becomes difficult and even meaningless unless the parties to the discussion agree on some common terminology. Innovation requires breaking away from old habits, developing new approaches, and implementing them successfully. It is an ongoing, collaborative process that needs considerable teamwork and skilled leadership. CEOs’ ability to lead their top management team successfully may provide the guidance and inspiration needed to support others to overcome obstacles and innovate. CEOs must provide effective leadership for top management teams to help organizations innovate.

It has been argued that, “There is no innovation without a supportive organisation”. Reviewed in the “International Journal of Organizational Innovation” by de Waal, Maritz, and Shieh (2010), innovation scholars have proposed numerous factors that, to a greater or lesser degree, have the potential to make organisations more conducive to innovation:

- A culture that encourages creative thinking, innovation, and risk-taking

- A culture that supports and guides intrapreneurial liberty and growing a supportive and interconnected innovation community

- Cross-functional teams that foster close collaboration among engineering, marketing, manufacturing and supply-chain functions

- An organisation structure that breaks down barriers to innovation (flat structure, less bureaucracy, fast decision-making, etc.)

- Managers at all levels that support innovation

- A reward system that reinforces innovative and entrepreneurial behaviour

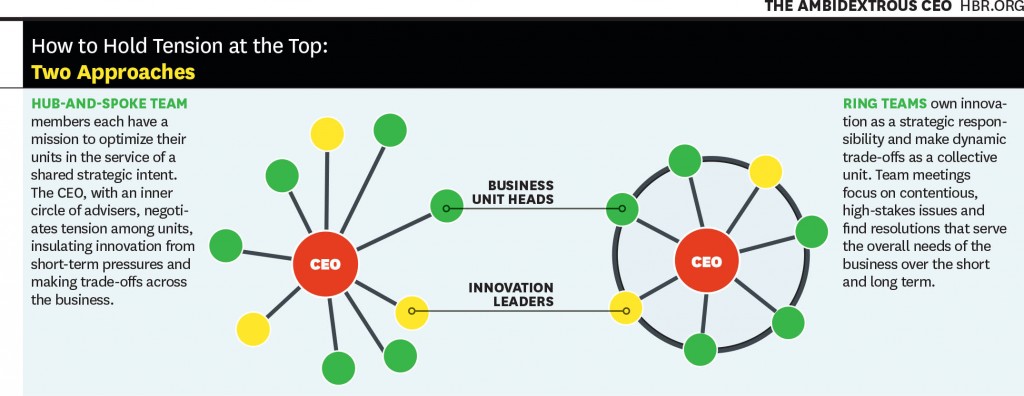

Communicating the vision, as described earlier, is also important for innovation management. This is a potential problem with KPMG’s Mark Britnell’s thesis of how raising the private income cap could promote innovation, as NHS and private wards nearly always co-exist in separate hospitals in ‘NHS Trusts’. It is argued in an interesting article in the Harvard Business Review (2011) entitled, “The ambidextrous CEO”, conflicts in innovation management are best resolved at the very top, and this could be filtered to the rest of the organisation through models such as “hub and spoke”.

It’s probably fair to say that a lot actually rests on the shoulders of CEOs in how innovative they wish their organisation to become. And certainly the ‘high-profile transfer of CEOs’, almost akin to the transfer of footballers, has attracted considerable recent interest, such as Burberry’s Angela Ahrendts joining Apple.

Thomas D. Kuczmarski in a rather sobering paper entitled, “What is innovation? The art of welcoming risk” identifies the CEO even as a potential ‘barrier-to-innovation’ (as far back as in 1996):

If you are like most CEOs, you are in a state of denial. Most CEOs express a fervent belief in new ideas and claim to be committed to innovation, but actions speak louder than words.

The truth is that most CEOs and senior managers are intimidated by innovation. Viewing it as a high-risk, high-cost endeavor, that promises uncertain returns, they are afraid to become advocates for innovation. However, because it clearly represents challenge and opportunity, most CEOs deny their reluctance to embrace innovation. They deny that their new product programs are underfunded or understaffed. They deny that they are closed to new ideas or ways of doing business. They deny that they fail to encourage or reward innovative thinking among their employees. Most of all, they deny that they have created within their organizations a fear of failure that stymies the urge to innovate.

All this denial is not good. It sends mixed messages throughout the organization and sets up the kind of second-guessing and playing politics that can undermine even the best developed business strategies. Unwilling to be measured by their failures, employees are reluctant to take risks that the successful development of new ideas demands and, as a result, even the desire to innovate diminishes.

Stevens (2010) himself has publicly expressed concerns on failure to innovate. For example, in the Harvard Business Review, he discussed how information on new clinical treatments spreads across the world quite fast, and how healthcare systems which fail to be flexible enough on picking up on this are likely to fail. Stevens’ example is striking:

However, the rate at which innovations are being translated into actual improvements is agonizingly slow — a frustrating problem that dates back to the world’s first controlled clinical trial in 1754. It proved that lemons prevented sailors from getting scurvy, but it then took another 41 years for a navy to act on the results. Wind the clock forward to today, and 15 years or so after e-mail became common, it turns out that most patients still can’t communicate with their doctors that way.

Deutsch (1973, 1980) proposed that how individuals consider their goals are related, very much affects their dynamics and outcomes. The basic premise of the theory is that the way goals are structured affects how people interact and the interaction pattern affects outcomes. Goals may be structured so that people promote the success of others, obstruct the success of others, or pursue their interest without regard for the success or failure of others. Deutsch identified these alternatives as cooperation, competition, and independence. In cooperation, people believe that as one person moves toward goal attainment, others move toward reaching their goals. They understand that others’ goal attainment helps them; they can be successful together. In competition, people, believing that one’s successful goal attainment makes others less likely to reach their goals, conclude that they are better off when others act ineffectively. When others are productive, they are less likely to succeed themselves. They pursue their interests at the expense of others. They want to ‘win’ and have the other ‘lose’. With independent goals, people believe that their effective actions have no impact on whether others succeed. Researchers have long debated whether cooperation or competition is more motivating and productive (Johnson, 2003). As regards the thrust of what happens in reality following 2015, therefore, the political landscape does very much happen. If Labour wish to promote collaboration perhaps through integration of health and social care, the entire nature of this dialogue will change. And the new CEO of NHS England will have a pivotal rôle in the organisational learning of the whole of NHS England.

Further implications for Labour in general policy

Some further issues are raised by Stevens (2010) short piece for the HBR. Labour has begun to ‘apologise’ for accelerating progress in the market of the NHS.

Introducing the ‘fair playing field’ of the market – another bogus concept which has gone badly wrong

The policy of ‘independent sector treatment centres’ under Labour has been much discussed elsewhere. PFI, although originally a policy which arose out of David Willett’s pamphlet for the Social Market Foundation (“The opportunities for private funding in the NHS“), and in the Major Conservative administration (see the work of Michael Queen), has seen various reformattings itself during successive Labour (Brown/Blair) and Conservative governments (Osborne/Cameron). The issue is that failing Trusts are not big to fail, unlike banks. Trusts ‘going bust’ are open to asset stripping from the private sector.

The opening up of the market is encapsulated in the document from Monitor, “A fair playing field for NHS patients”. Increasing the number of market providers not only potentially boosts ‘competition’ in the market, but also produces a supply of ‘predators’ in the terminology of Ed Miliband’s much maligned conference speech in Liverpool in 2011. This conference speech nevertheless successfully signposted with hindsight the highly celebrated political notion of ‘responsible capitalism‘. Many on the left now view the concept of ‘a fair playing field’ as being entirely bogus with the onset of decisions being made in the NHS on the basis of competition law not clinical priorities.

To what extent Burnham will wish to make a break from the past is the crux of the issue. Having signalled that he wishes to repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012) is the beginning of a long journey. At some stage, there will be a debate again about how much of the NHS is actually funded out of taxation, or whether, as anti-privatisation campaigners fear, whether we need to re-consider the explosive issue of co-payments or subsidiary payments. Burnham has signalled that he wishes to implement a NHS ‘preferred provider’ policy, in trying to capture lost ground on the increase in private provision in the NHS. But even here he may run into difficulty if legally the US-EU Free Trade Treaty, with discussions currently underway, make it impossible for him to implement such a policy.

But as it is, injecting ‘competition’ into the system could be in fact be the sort of competition which has dramatically failed in the energy sector. It is noteworthy that Ed Miliband has decided to whip himself up into a frenzy publicly about this in parliament, as part of the #costoflivingcrisis, rather than adopting the technocratic bureaucratic approach of waiting for the Competition Commission to investigate this particular market. It is well known that encouraging new entrants to the healthcare markets, even in the third sector, is fraught with difficulties, with the market occupied by a few well-known private sector brands. Here, the scandal of what are high prices, unlike ‘energy’, may remain a hidden scandal, as the customer is not directly the patient: it is the clinical commissioning group.

What do CCGs actually do?

Andy Burnham, to emphasise that he is not going to embark on yet another costly disorganisation in 2015, has explained that he intends to make the existing structures ‘do different things’. However, there is currently a bit of muddle as to what CCGs actually do.

Stevens states that:

Consolidation among care providers and barriers to entry for new hospitals mean that health-care delivery mostly relies on incumbents doing a bit better, as opposed to step changes in productivity from new entrants. Yet in the rest of the economy, new entrants unleash perhaps 20% to 40% of overall productivity advances.

Of course, with Stevens having leaving the NHS after ‘Blair times’, United Health has been set to become one of the beneficiaries of the advancing liberalisation of the NHS market.

It is now becoming more recognised that CCGs are in fact state aggregators of risk, or state insurance schemes. I had the opportunity recently of asking Sir Malcolm Grant in an exhibition at Olympia whether he had any disappointment that clinicians were not leading in CCGs as much as they could be, and of course he said “yes”. But strictly speaking GPs do not ‘need to’ lead CCGs as they are insurance schemes. The notion of ‘GP-led commissioning’ is widely felt to be a pup which was usefully actioned by the media to sell the controversial recent NHS reforms to a suspicious public.

This may or may not be what Stevens feels, albeit Stevens was speaking from the position of senior management in an aggressive US corporate at the time:

Increasingly, health plans should look to become ‘care system animators’ and not merely risk aggregators and transactional processors. Using their population health data, their information on clinical performance, their technology platforms, and their ability to structure consumer and provider-facing incentives, health plans have enormous potential to help improve health and the quality, appropriateness and efficiency of care. At UnitedHealth Group, our new Diabetes Health Plan, new telemedicine program, new eSync technology, and work on new models of primary care are all examples of what this can mean in practice.

Conclusion

In a perverse way, Stevens has an opportunity now to make the NHS work using knowledge of what the private sector does best and worst, in the same way that he was able to take advantage of his NHS policy knowledge while working for United Health. To what extent he will be concerned about the shareholder dividend of private companies as the NHS buggers on regardless will be more than an academic interest. No doubt the media will follow Stevens’ share interests with meticulous scrutiny.

The extent to which, however, he as the CEO can mould the culture of the NHS is an interesting one, however. If he (and ministers) believe that that it is he who should be leading change, then his default pathway will be one of private sector organisational change, with focus on patient safety and innovation through leadership. He will, however, run into problems if the NHS becomes primarily stakeholder-led. In other words, if patient campaigners continue to advocate that “patients come first“, especially through successful campaigning on patient safety or patient-led commissioning, Stevens might find his task is much harder than being a CEO of an American corporate.

Simon Stevens may seem like a powerful man. But there could be a man who is even more powerful from May 8th 2015, who might have a final say on many areas of policy, ahead of Stevens and Grant.

And that man is @andyburnhammp.

References

Birk, S. (2009) Creating a culture of safety: why CEOs hold the key to improved outcomes. Healthcare Executive (Mar/Apr), pp. 14-22.

de Waal G. A, Maritz P.A, Shieh C.J.(2010) Managing Innovation: A typology of theories and practice-based implications for New Zealand firms, The International Journal of Organizational Innovation 01/2010; 3(2):35-57.

Deutsch, M. (1973). The Resolution of Conflict. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Deutsch, M. (1980). ‘Fifty years of conflict’. In Festinger, L. (Ed.), Retrospections on Social Psychology. NewYork: Oxford University Press, 46–77.

Johnson, D. W. (2003). ‘Social interdependence: interrelationships among theory, research and

practice’. American Psychologist, 58, 934–45.

Kuczmarski, T.D. (1996) What is innovation? The art of welcoming risk, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 13(5), pp. 7-11.

Stevens, S. (2010) How Health Plans Can Accelerate Health Care Innovation, available at:

http://blogs.hbr.org/2010/05/how-health-plans-can-accelerate/

Toole, J.O., Bennis, W. (2009) What’s needed next: a culture of candor, Harvard Business Review, June edition, pp.54-61.

Tushman, M.L., Smith, W.K., Binns, A. (2011) The ambidextrous CEO, June, pp. 74-80.

Many posts like this have originally appeared on the blog of the ‘Socialist Health Association’. For a biography of the author (Shibley), please go here.

Shibley’s CV is here.

Does speaking out safely under the Public Interest Disclosure Act (1998) work?

The irony is that, if as a junior doctor you spend an extra three hours unpaid checking that all the results for your unwell patients are in, nobody will thank you, but if any mistake is made the system can come down on you like a tonne of bricks. This aggressive blame culture is at odds with the much-needed openness many love talking about but actually fail to practise. How clinical staff, and indeed managers, are able to speak out safely about problems in the system, such as inadequate levels of staffing for the clinical workload, has never been a more important issue as the NHS seeks to make £20bn efficiency savings in the next few years.