A Department of Health ‘easy read’ publication provides the “nuts and bolts” of “personal health budgets”.

The problem with initiatives from the Department of Health, these days, particularly is that quite a lot of energy can be put into selling the idea by non-clinicians, without much address to the evidence supporting the policies. The “Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge” is an unusually partisan initiative, curiously not involving all the political party leaders, raising ‘awareness’ of dementia, with very little discussion of the potential hazards of being given a provisional diagnosis of dementia for patients and immediates. But is the grass greener on the other side?

The attention also has turned to “personal health budgets”. One method of giving users significant choice and control is via the mechanism of a personal budget. This enables a person to be offered, in lieu of directly provided services, an equivalent sum of money, for them to purchase their own care and services. In the field of social care campaigning by various groups led to the setting up a set of 13 pilot projects for personal budgets in social care across local authorities in England from the end of 2005. Illustrating the dictum that it is often the case that policy drives evidence rather than the reverse, the care services minister at the time, announced that personal budgets were the future of social care, well before the evaluation was complete. Nevertheless the evaluation report did indicate that personal budgets provided increased choice and control and positive outcomes in terms of health and well being for most service user groups.

In fairness, this is not an invention of the current government. In fact, UK governments since 1979 have enacted a series of reforms to public services in this direction. For example, The Thatcher government in the UK (1979-1990) introduced market forces into health and social care via the formation of the internal market in the NHS, and a similar separation of purchasers and providers in social care with the introduction of the Griffiths reforms and the 1990 NHS and Community Care Act. The New Labour government (1997-2010) very much continued the direction of travel with further reforms to public services aimed at increasing diversity, influence and choice for users of public services. Of course, the fundamental problem with introducing this Darwinian ‘survival of the fittest’ approach to natural selection of healthcare providers is what happens if healthcare providers go out of business; this ultimately could lead to ‘missing gaps’ in the health services, or some services being under-represented. This is likely to be the case in high street law, where more profitable areas of law, such as commercial and corporate, are likely to do better than less sexy sectors, like housing, immigration, and housing. The coalition government elected in 2010 was quick to produce plans for change in the NHS, in the white paper ‘Equity and Excellence’. This document makes it very clear that the theme of patient choice will be even more central to health policy using mantra such as “The NHS also scores relatively poorly on being responsive to the patients it serves. It lacks a genuinely patient-centred approach in which services are designed around individual needs, lifestyles and aspirations”, “We will put patients at the heart of the NHS, through an information revolution and greater choice and control”, “Shared decision-making will become the norm: no decision about me without me”. The ultimate pièce-de-resistance was to implement, of course, the Health and Social Care Act (2012), cheekily implemented given that neither the Conservatives nor the Liberal Democrats won the election, and none of the Medical Royal Colleges or BMA were involved closely in the implementation of these complex, costly, reforms.

Personal budgets are already being used for some social care recipients and health budgets are now currently being trialled in some primary care trusts. Although the NHS Confederation’s report has previously provided that the budgets can help personalise healthcare, it says NHS managers are concerned the risks could outweigh the benefits. Shaping Personal Health Budgets – a view from the top originally found many NHS leaders were “uneasy with the fervour of some proponents” who, it said, could make claims beyond the supporting evidence. NHS managers interviewed by the confederation’s researchers said frank discussion of patient safety and cost risks associated with personal budgets was hindered by the “evangelism” of enthusiasts and that most NHS leaders were uncertain of any impact of mini budgets.

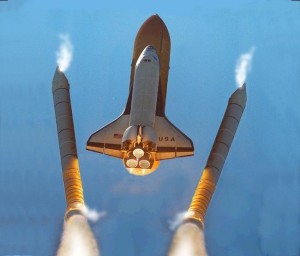

This is bound to be a continuing priority of all the NHS regulators, and it will obviously be concerning that booster rockets are being given to personal budgets, at a time when the National Patient Safety Authority is being abolished. The budgets are intended to encourage providers to be more responsive to patient preferences as patients can avoid poor providers. But managers are concerned this will lead to double running costs as patients will move only gradually, requiring the NHS to cover the fixed costs of an unpopular service as well as the personal budgets of the patients.

This is bound to be a continuing priority of all the NHS regulators, and it will obviously be concerning that booster rockets are being given to personal budgets, at a time when the National Patient Safety Authority is being abolished. The budgets are intended to encourage providers to be more responsive to patient preferences as patients can avoid poor providers. But managers are concerned this will lead to double running costs as patients will move only gradually, requiring the NHS to cover the fixed costs of an unpopular service as well as the personal budgets of the patients.

So a critical issue determining the success of any innovation must be how have the lead adopters responded? Personal health budgets are a good idea ‘in principle’, but variation in how they are applied could create damaging inequalities between patients, according to the Royal College of General Practitioners. In a letter to the Government, the RCGP has said it wants to work with the Government on setting up a stricter policy framework for the scheme, which gives patients with long-term conditions cash budgets to spend on care. However, it raises concerns that the personal care budgets are being used for ineffective treatments and that commissioning bodies are applying widely different policies for how patients can use their budgets in different areas of the country. A full evaluation of the pilots is due to be published later this year, although the Department of Health has already committed to giving a personal health budget to everyone who receives continuing care by 2014 and giving all eligible patients the right to one after that. And that of course has always been a central issue for many – does patient choice also include medical interventions which may or may not work? This is clearly an interesting development from the point of view of complementary medicine for several reasons. Firstly, the fact that the kind of NHS users who are being offered PHBs are typically the kind of people who use complementary therapies, i.e. those with chronic, long term conditions who tend to consume a lot of NHS resources and who do not experience significant benefit from these NHS interventions Secondly the fact that there is good evidence that many of those who would most like to access complementary therapies are prevented from doing so for reasons of cost and access15e17 and that PHBs may provide a new mechanism of access for many people. No professional would wish to offer a treatment that does not work, because of the principle of ‘primum non nocere‘, but what about interventions with little objective evidence base (as yet) but which might offer ‘perceived benefit’ for the patients? Such examples might include, for example, as described recently in the HSJ as follows.

During this, one patient who suffered from depression used the budget to pay for a therapist and to begin a dress-making hobby. Another who suffered from chronic lung disease used the money for singing lessons. A male patient with motor neurone disease used his personal budget for a modified

Patients ultimately will be able to access the budgets through their local NHS. They will have to work with clinicians to decide how to best spend the money to benefit their health. Ministers are investing £1.5 million in the hope that by 2014, it will be available to 56,000 people on the NHS Continuing Healthcare scheme. This scheme is for patients who suffer from complex medical conditions who require a lot of care and support. Norman Lamb has said he hoped the budgets would in time be made available to others. Michelle Mitchell, charity director of Age UK, has said:

“So long as personal health budgets are well organised and easy to use, they will help a significant number of older people to plan and be in control of their health care. Personal health budgets will not suit everyone, and may present confusing choices for some vulnerable older people struggling with illness or dementia. It is therefore essential that everyone who wants a personal health budget is well supported with the right advice and information, and those people for whom a personal health budget would not be appropriate, should not feel pressured into taking one up.”

There is also concern about what happens if a patient spends all their budget too fast, while some critics argue the initiative is a way of introducing fees for NHS services by the back door.

As they say in management, this is “work in progress”… Maybe, as tends to be the case, the grass is not necessarily greener on the other side.

Evaluation of the personal budgets pilots