If one thing “can be taken as red” from the interference by politicians introducing market mechanisms into the NHS, it is that there will be ‘entrepreneurial’ people; perjorative though this sounds, some of them will be gaming the system. Some of these initiatives may come under the general rubric of “rent-seeking behaviour.

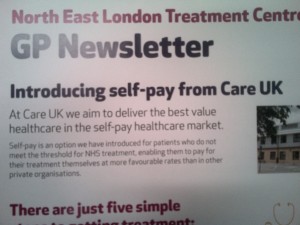

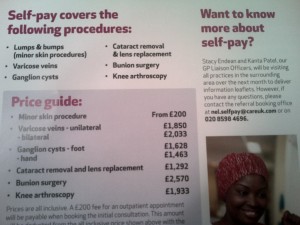

Martin Rathfelder (@SocialistHealth) described on this blog yesterday in his blogpost two recent examples of “self-pay” from CareUK (images below from the same blogpost):

@richardblogger indeed observes this phenomenon in relation to assisted conception at King’s and at the Homerton (see his blogpost here), and cursory search on Google (link here) finds a number of Trusts using the same wording for these services.

@richardblogger indeed observes this phenomenon in relation to assisted conception at King’s and at the Homerton (see his blogpost here), and cursory search on Google (link here) finds a number of Trusts using the same wording for these services.

This phenomenon has been growing in prominence, with Prof Clare Gerada (@clarercgp) having remarked on it in a previous Telegraph article [extract dated 24 Sep 2012]:

“GPs believe the numbers of patients asking about paying for operations including cataract removal and joint replacements has increased markedly in the last year, according to a poll. Dr Clare Gerada, chairman of the Royal College of GPs, said it was “incontrovertible” that increased NHS rationing was behind the increase in going private, a trend she described as “very sad”. The poll, carried out by ComRes for the firm BMI Healthcare, found that 70 per cent of GPs are now unable to refer a patient for further treatment on the NHS at least once a month because they do not qualify under local criteria.”

And the existence of this phenomenon has been made clear to another section of the population, the Daily Mail reader (for example in this article here).

What is intriguing, as observed by @richardblogger, is the precise wording of the Care UK advert:

“Self-pay is an option we have introduced for patients who do not use the threshold for NHS treatment, enabling them to pay for their treatment themselves at more favourable rates than other private organisations.“

This advert is in a GP magazine, and the provider is comparing themselves to other private organisations, not the NHS. They are therefore advertising to GPs, selling the same product but via a different route (or “micromarket”), and this is possible because the patient will trust the GP, as Richard observes.

This is significant for two classic textbook reasons in marketing.

First of all, it is feasible for the price for the Care UK product to be set higher than the price for the NHS product, as there is “price discrimination” going on – with the same product being sold to different markets (in one GPs, in the other the patient themselves). This is called “third degree price discrimination”, as helpfully defined here by Wikipedia:

Secondly, it is an interesting example of how prices are set in any market. One method of setting a price is to add up how much a product costs, and to sell it onto the consumer at a price which represents how much it cost to make the product with ADDED ON how much you think a consumer is willing to pay for it with any extra – i.e. “profit”. This is “cost-based pricing”. Another method is setting a price comparable to your competitor’s, but hoping that in a direct head-to-head the consumer will choose your one. This example of Care UK is interesting as it represents “value-based pricing” (link here), representing the “notion of value” the consumer will have for having Care UK provide the product. This is akin to why you would wish to go into a supermarket and pay triple for a jar of coffee which is essentially very similar to a jar of coffee of the same type sold in the “value range”. The fact that Care UK has sold the product to the GP rather than the patient himself or herself can be interpreted as a reflection of how much a GP might be willing to pay for it on the customer’s behalf (neither the GP or the patient is directly out-of-pocket but clearly private health providers will be seeking to ensure a shareholder dividend through their services in the NHS.)

Interestingly, the situation is different to Warrington and Halton Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust which has introduced instead “My Choice” (see here).

However, here there is a critical difference:

“Importantly, the fee charged is only the standard NHS cost for the operation or procedure. We do not charge an increased private price. It means that your patients. still access these procedures at your first class NHS surgical centre. They only pay the standard NHS price and will be treated to the high quality and safety standards that we have in place at Warrington and Halton Hospitals. The fee they pay goes directly into patient care at the hospitals.“

And here’s the rub. If you’re a patient, exerting patient choice, and if you’re paying for the repair of your varicose veins, you may prefer to go to your local A&E department than to present to your GP who may be offering the same treatment for a higher price, because of the effect of these marketing mechanisms. There is therefore an internal price discrepancy already in this privatised “neo NHS” market. Indeed, if you present with a complication of a varicose vein (as indeed the impetus for removing varicose veins is not simply cosmetic), and the list of complications is one which every medical student is obliged to learn before qualifying (link here), the NHS will treat you on the spot anyway.

I’ve often discussed in recent posts how the privatisation of the NHS throws up dangerous situations professionally, but in the name of patient choice the idea of a patient deliberately having to wait to maximise his or her chance of receiving acute medical treatment which is much cheaper (known to economists and behavioural neuropsychopharmacologists as “temporal discounting theory”) is a deplorable one and professionally repugnant.