Andy Burnham MP spent much time in addressing how combined health and social care approaches were vital in dementia, and for example was instrumental in establishing the Dilnot report. Rather awkwardly, I have found a viscerally hostile response for a well-meant desire to improve the wellbeing of patients with dementia coming from GPs themselves, with some people, who are doctors, saying that “empowering patients” are big words and mean nothing. I cannot even begin to explain how disappointed about this I am, as failing to address the quality-of-life of patients in this difficult time is clearly not desirable, socialist health system or not.

I have been latterly bombarded by some GPs with arguments as to why individuals should not be given an early diagnosis of dementia, saying it can destroy relationships. GPs owe a primary duty of care to their patient, and are expected to observe confidentiality, so there are further issues there as well as the central pillar of ‘primum non nocere’, at first “do no harm”. However, GPs are expected to tell the truth to their patients of course, and part of the big issue in policy is that individuals are scared from getting a diagnosis for the symptoms for fear of stigma. And why should a person who is worried not receive help from a GP? For a younger patient, which a GP is likely to refer on, it is important to consider early-onset familial Alzheimer’s Disease, which takes the argument into a different realm of genetic counselling. It is not only a Department of Health drive, but also an international drive (and has been for some time). There are certainly operational issues in that GPs cannot possibly refer on all people to memory clinics and or primary care as that would overload the system, but there is all the time more sophisticated research into the sensitivity and specificity of screening tools in the community (e.g. GPCOG in Australia). Certainly, a GP will need to use some judgment, as it is not inconceivable that a busy GP might miss the one-in-a-million temporal lobe glioma presenting as memory problems as accelerated ageing or dementia, missing that space-occupying-lesion which should be referred. But primarily I feel that GPs who do not wish to give individuals with dementia on account of it doing more damage than good are complicit in an agenda where it is treated as a ‘death sentence’ – this is wrong on so many different levels, not least because a huge amount can be to help people with dementia with their environments, in adding ‘life to years’ through empowering them through their environment. I will briefly address this at the end of this blogpost.

Prof Alistair Burns, @ABurns1907, this morning launched the awareness campaign launched today on 21 September 2012 to coincide with World Alzheimer’s Day, as part of the Prime Minister’s Alzheimer Challenge launched in March 2012.

Alistair is the National Clinical Director for Dementia here in the UK. The diagnosis is an important component of an individual’s journey in dementia care. This diagnosis explains symptoms for the first time so that the individuals concerned can understand, allows appropriate treatment to be started (this could be pharmacological, but also could well be non-pharmacological interventions aimed at improving symptoms or quality-of-life), empowers individuals, and, most importantly, averts crises. It can be a difficult conversation to encourage people to seek help from their GP, and this campaign is part of this process. I think it’s absolutely fundamental to encourage people to go to see their GP. Many people may not have dementia (might have depression, or something totally different), but it’s important that a GP gets to the bottom of it. We should try very hard as a society in trying to squash any stigma associated with a diagnosis of dementia, whether in its initial diagnosis or in ongoing support (for example through ‘dementia frjendly communities’). We now live in an age where there is a lot of enthusiasm (and increased resources) for “person-centred care”; many individuals with dementia will spend much time of their patient journey with social care services, so the initial diagnosis is just the very first step. A very important first step.

Click here on the link to an audio produced by Alistair for the Department of Health’s initiative.

As an academic, I am extremely keen to support this. I will be going in December 2012 to Hyderabad, for the Biennial Meeting of the World Federation of Neurology meeting. You will see even from our program for this year’s meeting that dementia can present to experienced physicians under a number of different guises, ranging from memory problems (amnesia) to problems doing maths (acalcula) or problems reading (alexia).

I did my Ph.D. at Cambridge with Prof John Hodges in the early diagnosis of a common type of dementia in younger patients, called the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia between 1997 and 2001. I published my findings in the journal in Brain in 1999, and this paper has now become a classic, cited by all the major labs in the world. In this paper, I provided for the first time a solution to the mystery that such patients were presenting to the memory clinic with very profound behavioural and personality change, unnoticed by them but totally obvious to their immediates such as friends or partners. And yet such people performed very well on standard neuropsychological assessment, and often had perfectly normal brain scans and brain electrophysiology.The solution to my problem in short is that all the traditional neuropsychology were testing the wrong parts of the brain. In this condition, the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia, there are profound changes in a part of the brain near the eye, the ventromedial or orbitofrontal cortex. It is very difficult to demonstrate that an invididual has a thinking changes unless you test specifically the right type of thinking, which I did. I found such patients universally to be prone to making excessively risk-taking decisions. I found that virtually always their memory and other abilities such as memory, spatial working memory or planning were normal.

Early diagnosis I feel is absolutely critical, as it empowers patients and their families with a credible explanation of problems, which they have previously been unable to discuss. Once they know this diagnosis, they can seek support from the NHS, including specialist NHS clinics, and, where appropriate, medications, such as for memory early on in the condition (cholinesterase inhibitors), or medications for some of the more severe symptoms once the dementia becomes advanced. The NHS has latterly treated dementia as a top priority, and the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge is a landmark initiative by the Department of Health to put on a firm base the importance of dementia, given how resources are tight and many conditions (such as chronic obstructive airways disease).

I think it is important to give individuals realistic expectations on their pathway through a diagnosis of dementia. There is at the moment no cure for treatment, whilst there are effective treatments for some of the key symptoms. I think above all the success of the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge so far has been immense in giving people hope, and making people feel that they are not alone. I had the privilege once of doing three months as a junior in the early 2000s in the clinical team of Prof Martin Rossor, at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery. Dr Nick Fox, Dr. Huw Morris, Dr Jason Warren and Dr Giovanna Mallucci were my Specialist Registrars, and they are now a Professor and 3 Consultants respectively.

In those days, a patient with queried dementia would be admitted on Monday to the National. I would take a 2 hour history with them, confirmed by a Specialist Registrar. I would always have to take a history from an informant, somebody who knew the person well. The problem is that some individuals, such as with behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia, have virtually no insight into their condition. All individuals would have a MRI, cognitive psychometry and an EEG, and a full set of bloods (which always included screens for the rarer disorders, infections, and neurogenetics for systemic medical conditions known to cause dementia, where it might assist in diagnosis). All patients, if there was no contraindication, would receive a lumbar puncture for examination of cerebrospinal fluid. I remember this being usually the most difficult time of the week, as I had to make sure the results were back for the ward round on Thursday morning. Then Martin would review all the information, with his Registrars and Clinical Fellows, and, as a world expert, would arrive at the diagnosis.

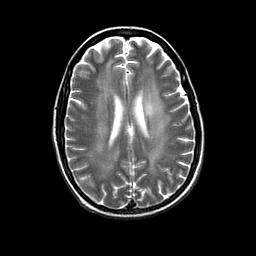

I remember one patient in particular. I will of course not give any identifying details, but he was a dancer from West London. He had presented with an insidious cognitive change in thinking and some subtle change in his personality (not known to him). The issue was, however, that he was in his late 30s, and this would have been a very unusual presentation of Alzheimer’s Disease (although some early presentations do exist). The cerebrospinal fluid had a massive white cell count (I remember being totally shocked when I read the result for the first time), and I presented a MRI similar to this to Dr Stevens, eminent neuroradiologist at the National.

Prof Rossor agreed with Dr Stevens – and it matched all the other investigations. This man had HIV dementia as a first presenting feature of AIDS, and was then referred to University College Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust for triple therapy. This was a clear case of where knowledge was power.

I strongly recommend you to tell people you know in society about the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge. Just because I do not vote Tory (and vote Labour), I am very willing to support this challenge. To help with this Challenge, I am currently writing a 250 pp book on wellbeing in dementia. For this, I have received a number of papers from various academics: Prof Felicia Huppert (definition of wellbeing in dementia), Prof. Peter Lansley (socio-economic rationale for wellbeing approaches), Prof Facundo Manes (social cognition and contexts), Prof Marcus Ormerod (built environments), Prof Roger Orpwood (assistive technology and telecare), Prof Andrew Sixsmith (ambient environments), and Prof. Catherine Ward Thompson (art and dementia). Prof. John Hodges (my PhD supervisor from 15 years ago) has kindly agreed to write the Foreword to my book which he says is “desperately needed”. I have also been very much influenced by the seminal work at Stirling on design of the home, led by Prof June Andrews and Prof Mary Marshall.

I am gradually arriving at a synthesis of their work, and I write daily on a blog especially devoted to wellbeing and dementia. To engage people who might not realise the crucial importance of dementia I publicise the importance widely on my @dementialives and @legalaware Twitter threads. I am also very excited that there will be a further chapter on innovation, which I feel is critical to the NHS (I came top of the year in my own MBA in innovation management earlier this year), and personalised care, to be written by somebody who is absolutely devoted in this field.