Home » NHS Management

Sir Stuart Rose’s medicine for the NHS may be too generic

What lessons can be learnt from reviving Per Una underwear to the 14 Keogh Trusts?

The left wing does business too.

Look at Alan Sugar.

Or maybe not.

Sir Stuart Rose, who was credited with rejuvenating Marks & Spencer during a turbulent six years as chief executive, has been hired to help revive the fortunes of failing hospitals in England.

In “Back in Fashion: How We’re Reviving a British Icon”, Sir Stuart Rose establishes his thinking about turning around the fortunes of Marks and Spencer, in an article in the Harvard Business Review.

In this article, Rose explained that he was a temporary “guardian of this great business and that my job is to leave it in better condition than I found it.”

On his eventual demise, Rose wants people to say, “He could have turned left but, thank God, he turned right.”

This of course is a tongue-in cheek reference to his known sympathies for the ideology of the Conservative Party. But on closer inspection his transformational agenda is not particularly right-wing in the sense that the principles are generally widely held.

In a move dubbed in Whitehall as “M&S meets NHS“, Rose will advise the health secretary Jeremy Hunt on how to build up a new generation of managers to transform failing hospitals. There will be a particular focus on the 14 NHS trusts placed in “special measures” last year.

One of his criticisms is that major decisions were being made by people not experienced enough to make them. But it will be interesting to see how he deals with CEOs of English Trusts, who are not clinically trained, who achieve good four-hour wait targets. And yet the management plans of the patients leaving A&E in those Trusts can be an unmitigated disaster for patient safety. Often, frontline staff in such Trusts are totally disenfranchised, and even discredited by their management.

“For those outside the UK, it is difficult to understand just how powerful the M&S brand is. It is a national institution. Two prime ministers, Margaret Thatcher and John Major, both famously said they bought their underwear at Marks & Spencer, just like nearly a third of the people in the UK.”

And of course the NHS is a powerful brand.

Rose is clearly a marketing guru at heart. The brand is so powerful that even private providers are allowed to use their intellectual property to market their services.

The early events Rose experienced are very revealing.

“Clearly, the battle hinged on our ability to convince reporters, analysts, and investors that I was the one to lead M&S back to prosperity. Having such intense scrutiny of you personally, as a leader, can cause self-doubt.”

One of the issues about Sir David Nicholson’s ability to lead his organisation is the extent to which he appeared ambivalent about the events at Mid Staffs.

Mike Farrar has also had such problems with the media.

Rose has previously spoken about the the “rock star” image and PR skills needed for those at the top of the world of business and politics. One thing that Nicholson and Farrar can’t be called are ‘rockstars’.

Rose warns, “Don’t Even Consider a Plan B”.

And yet it’s this ‘there is no alternative’ narrative which is causing disquiet for people running the NHS.

People are more than aware that some McKinsey ‘efficiency savings’ have in fact led to dangerous staff cuts in certain Trusts, compromising patient safety.

In “The only thing wider than the NHS funding gap is the policy vacuum’ by Colin Leys published in the Guardian today, Leys considers a number of different proposals for the ‘funding gap’.

Leys remarks,

“As a result, there is a policy vacuum, which the private health lobby is eagerly seeking to fill with renewed calls for charging and “top-ups”; in reality, these would do little to close the funding gap, but would mean the end of free and equal care for all. In the meantime, it seems that in official circles it is left to everyone except Hunt to suggest solutions: more “efficiency savings” (Sir David Nicholson); rationalisation, with fewer hospitals offering specialist care (Sir Malcom Grant); more specialist GPs and intermediate care provision (NHS England’s Dr Martin McShane); more self-care (NHS clinical commissioners); more telemedicine (the joint government-industry 3millionlives project).”

“As it became clear that one successful line could not, in reality, fuel a sustainable revival by itself, M&S suddenly discovered the allure of consultants. But for a company that had long prided itself on home-growing talent, the heralding of consultants to bring in “fresh” ideas sent a damaging message throughout the ranks.”

It is well known that the NHS has had trouble in generating home grown talent in management, symbolically heralded by the appearance of Simon Stevens from an US healthcare provider to head up the NHS.

“One of the most important messages I wanted to send to our staff was that they should trust their own judgment again.”

But this is the very essence of one of the toxic problems of the NHS.

Certain frontline staff, especially juniors, don’t have a say on what is going wrong with patient care, because of some seniors pursuing targets. If Rose is serious, he will need to talk to frontline staff to find out what problems there have been with patient care, and why.

He may find a lot of it does come down to the fact there is an unsafe staffing level, but they’ve had no-one to report their concerns to in a meaningful way.

Another problem comes to analysis of the ‘offering’.

“Then we made changes closer to home. The most symbolic thing we did was to have a massive housecleaning. Because there were so many different subbrands in our shops, we had lots of signage and titles and names on cardboard cluttering up our stores.”

Between NHS hospitals in the round, they need to offer a comprehensive offering, and not miss out any rare diseases. But here the acccusation for cherry-picking for profitability becomes particularly pertinent.

The difference in ethos between the NHS and M&S has parallels with the differences between UK state prisons and US private prisons.

In US private prisons, prisoners are able to pay for a better room – in other words, as US prisons are designed to make money, this creeps into other activities of prisons.

“The stores looked dated. We weren’t in the same league as trendier retailers like Zara, Next, and Topshop. It was the beginning of a major store-by-store refurbishment program, which cost us more than £500 million by the end of 2006, with an additional £800 million earmarked after that.”

Many people are indeed impressed by the brand-new spanky new hospitals funded by PFI, but find horrific the idea of hospitals looking like hotels a bit nauseating if there’s insufficient money to staff them properly.

But Rose is known to be very keen on showing visibly the hallmarks of his ‘turnout’.

Presumably Rose will want there to be external markers of turning around the Keogh Trusts.

But that’s admittedly another problem, and why Rose’s medicine is ‘too generic’. It is all too easy for clinical staff to be forced to cover up bad care because of not wishing to get into trouble with their regulators and a lack of duty of candour (not necessarily working independently.)

The danger is that the Keogh hospitals end up ‘looking nice’ but are still as dangerous/safe as previously.

“Having cut so many staff from a business as culturally embedded as ours, I had to spend probably 90% of my time over the next six months convincing people who were already pretty disillusioned that we were making progress.”

It’s well known that Rose cut thousands of staff to stem the fall in drop in profits.

The problem with the NHS, more so than with M&S possibly, is that it might be easier to find alternative employment for staff in the NHS about to be made redundant.

And the idea of the need to make staff redundant is still a problematic one for the NHS.

This is because, despite the urge for ‘efficiency savings’, the demand in the NHS has been traditionally described in rather hyperbolic terms such as “exponential”. In other words, the messaging problem for those who want to cut staff numbers in the NHS is that the demand on the NHS is huge.

And if the Government wishes to feed the demand, such as a ‘seven days a week service’, the demand is by definition going to get greater, unless you literally vary unilaterally employment contract terms for Consultants and their junior staff.

It is said, furthermore, that Rose is known for taking a personal interest in his customers’ thoughts on his products – he once arranged a meeting with Jeremy Paxman following the BBC presenter’s criticism of M&S men’s underwear.”

But the actual experience of many who have complained about the NHS is that complaints get sat on.

Rose was knighted in 2007 for services to the retail industry and corporate social responsibility, had worked his retail magic.

But corporate social responsibility in the NHS will not be achieved by green light bulbs or clever marketing.

There needs to be a genuine ‘investment in staff’. Trades unions for nurses and other clinical staff cannot be any longer totally ignored in policy decisions regarding the NHS.

The Health and Social Care Act (2012) was itself a monumental failure of the mantra, “no decision about me without me.” So were the decisions about the Lewisham decided in the second and third highest courts of the land.

“We’d also finally regained our stride in advertising and marketing. We led from the food side of the business, because it had suffered less than the clothing side and for that reason was seen as our stronger asset.”

For the NHS, Rose will have to concede that a bone marrow transplant for a rare blood disorder is as important as a hernia operation for the patient involved. But this is where a left-wing twang, regarding equity, might be significant after all.

How will Rose know when his Trusts have got better?

A cosmetic refurbishment, realigment of the product offerings, or better marketing are not the solutions.

They are too generic for retail, and not appropriate for this sector.

As someone else might say, he is hitting the target but missing the point?

The vision to lead the NHS

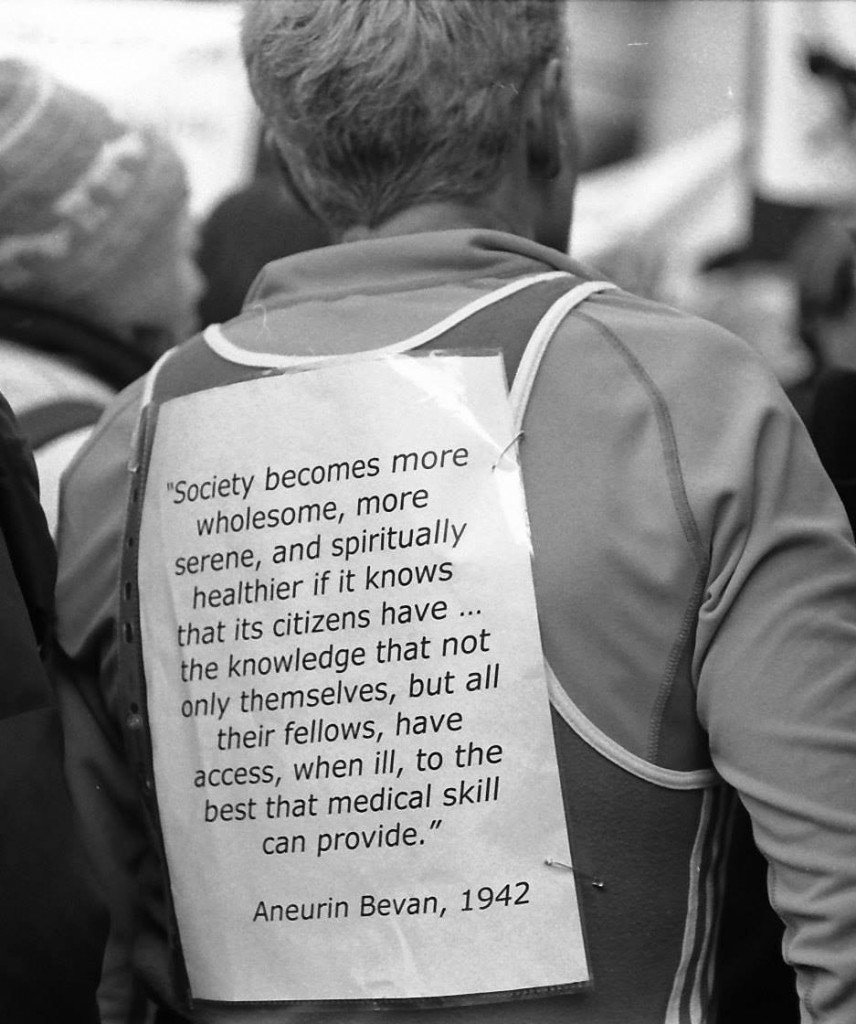

If you look at this person’s billboard, you’ll find a very short passage from Aneurin Bevan from 1942.

Aneurin Bevan had his critics too. Bevan would often comment that the Labour Party was not inherently socialist: citing that one in five members of Labour at the time were truly socialist.

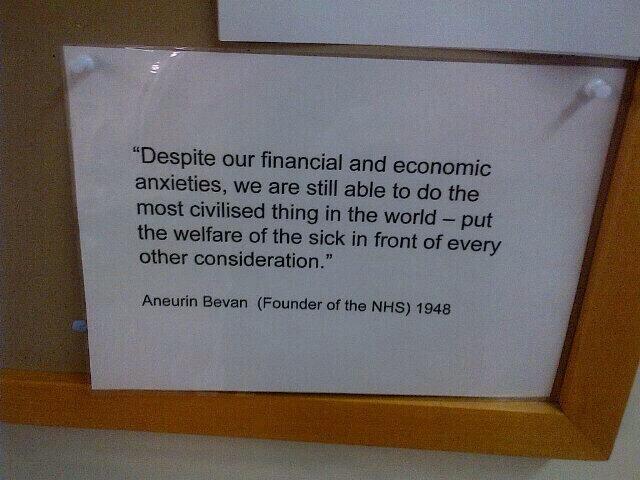

Still, Bevan and Attlee carried on regardless. Here’s a comment from Bevan from 1946.

Bevan left school at 13. He didn’t go to Charterhouse and Oxford.

The vision of the creation of the NHS is indeed one of the things which truly shocks critics of socialism. And for decades various Governments have been trying to undermine the National Health Service.

You can in fact tie yourself in knots over definitions of socialism, but certainly equality of opportunity for treatment and care (equitable access), solidarity, cooperation and collaboration might be strands. The idea of efficiently planning resources for the greater public good of the country might also be in the mix.

Lloyd George himself said it would be indecent for a democratic dictatorship to emerge from the National Government which had been put on a “war footing”.

Cameron and Clegg put us on a war footing, despite not having won the 2010 general election. But the war footing was to use the five years to extract as much money out of the public service and outsource it to the same bunch of people, as per outsourcing and privatisation of NHS, probation services, Olympics or workfare. These people are in the private sector.

Diverting resources from the public sector to the private sector is privatisation.

The result of this war footing for the NHS was an Act of parliament which did not have a single clause on patient safety, apart from the abolition of the National Patient Safety Agency; so it is rather ironic and foolhardy perhaps that Jeremy Hunt would wish to campaign on this issue.

The 493 page Act of parliament has been used to spin a number of lies, such as GPs being in the ‘driving seat’. CCGs, or clinical commissioning groups, are simply insurance schemes which apportion risk to local populations, and work out how much money should be alloted to them for their future care or treatment (and how it should be spent.)

They are conceptually the same as the “health maintenance organizations” (sic), borrowed from the United States.

The absurdity of it is that the NHS was borne out of the failure of private insurance approaches before the War, so why should we wish to return to an inequitable fragmented country which the Attlee government had tried so hard to repair?

That war footing for the NHS was a convenient way to shoehorn in that famous section 75 and its Regulations which provided the jet engine for a market – competition. This market needed to be ‘regulated’ (in as much as the cost of living crisis has demonstrated the failure to regulate an oligopoly of companies which can legally collude in setting prices). And there needed to be a régime for fast managed decline of NHS trusts.

Private markets are fragmented, and always introduce “transaction costs” leading to waste and inefficiency. Directors of private limited companies have a primary duty to make a profit for their shareholders, and that’s the case even if you’re using the “NHS” as a logo or kitemark.

And you can take treatments out of scope. This is rationing. It happened under the previous Government, is happening under the current Government, and will happen under the next.

And it cost £3bn – money which could have been better spent elsewhere, such as on the frontline.

The myths keep on coming and coming and coming.

Who’s going to pay for the NHS going seven days a week? Are NHS Consultants simply going to accept a unilateral variation of contract with no mutual agreement? It might be a case of ‘see you in court’.

The next Labour government needs to set out a vision which can inspire the general public, and equally importantly inspire the staff of the NHS.

The staff of the NHS do not want to be told that ‘a culture of evil has become normal’ by the Secretary of State for Health. They want some dignity and respect too.

They don’t want a technocrat who can implement textbook ‘transformative’ leadership, such that they can turn their NHS Trust into the healthcare version of a motor car production plant.

They wish their views to be respected, and where they can speak out safely where something goes wrong.

Nobody’s ever dared to discuss with the public the effects of PFI on local economies, or the billions of efficiency savings, but, if indeed ‘transparency is the best disinfectant’, we need all major political parties to speak openly about this issue.

It might be that “clinical leaders” need to grow some balls where possible to neutralise some who are overly aggressive NHS management seeking to balance budgets and hit targets at all costs.

I’m sorry if this sounds like a rant more fitting for a left-wing version of Katie Hopkins (perish the thought).

But we need a vision.

That vision is the SHA.

Simon Stevens. Is it not where you’ve come from, but where you’re going to?

The new NHS England Chief Executive is Simon Stevens.

Hailed as a ‘great reformer’, the first accusation for Simon Stevens is that he has been parachuted in to change the culture of the NHS. For all the recognition of patient leaders and home-grown leaders in the NHS Leadership Academy, it is striking that NHS England has made an appointment not only from outside the NHS but also from a huge US corporate. Indeed, Christina McAnea, head of health at the union Unison, told the Today programme on BBC Radio 4: “I am surprised that they haven’t been able to find someone within the NHS.”

A person like Stevens is likely to bring a breadth of managerial experiences, although he has never done a hospital job. He is no expert in land economy either. Despite the drama, the transition of the NHS to a neoliberal one has been on a fairly consistent course, as I explained previously in a now quite famous blogpost. I have also discussed how competition was introduced as a major plank in the Health and Social Care Act (2012) despite the overwhelming evidence against its implementation, known at the time; and how the section 75 and associated regulations would be the mechanism to achieve the ‘final blow’ for liberalising the NHS market. Where possibly English health policy experts have failed, perhaps, in their overestimation of the predeterminism that has taken place in England’s health policy since 1997. Changes of government have brought with it various changes in emphasis, such as the Blairite need to ‘reform public services’, possibly away from a socialist centre of gravity. The changing health policy has also had to take on board changes in politics, economics and legal considerations in the last few decades.

The suggestion that NHS England could have chosen ‘a more socialist CEO’ in itself is fraught with criticisms. Can you ‘a bit’ socialist or ‘half socialist’? Indeed, can you implement a ‘socialist NHS’ without implemented a sharing of resources across various sectors, including education or housing? People who don’t wish to engage with such arguments often end up with extremist Aunt Sally arguments referring to socialism as a state like pregnancy or like a religion, but the ideological question still remains can you have state provision of the NHS on a sliding scale from 0-99% private provision? With the current debate about whether Labour would renationalise the railways, in light of the fact that monies are potentially found out of nowhere for foreign military strikes at the drop of a hat, this discussion has never been more relevant potentially. One of David Cameron’s famous phrases, somewhat ironic given his background at Eton and Oxford, is, apparently: “It’s not where you’ve come from – it’s where you’re going to.” This may apply to not only Stevens but the whole of NHS England, especially if you hold the alternative viewpoint that the NHS could and/or should jettison its ‘founding principles’.

It is all very easy to play the ‘man’ not the ‘ball’, and certainly NHS England already has its strategic goals. Nonetheless, it is critically important for any organisation, particularly the NHS, to think about how much of its strategic aims have to be driven from the very top. Attention has turned to the US company he has spent the last decade with as a senior executive: United HealthCare. There is no point, however, being necessarily alarmist. Pro-NHS campaigners will be mindful of this now largely discredited campaign. Resorting to such emotive messaging may distort the genuine discussion which needs to be had about the future of the NHS in England.

Mr Stevens, 47, was Tony Blair’s health advisor between 2001 and 2004, and before that advisor to then-health secretary Alan Milburn. Simon Stevens’ CV reveals that he was a Trustee from The Kings Fund, London (a health charity) between 2007 – 2011 after being a Councillor for Brixton, south London London Borough of Lambeth 1998 – 2002 (4 years). It has even been alleged that Stevens has been a member of the Socialist Health Association. The NHS budget has been notionally protected – it is rising 0.1% each year at the moment – the settlement still represents the biggest squeeze on its funding in its history. Labour has criticised previously how the Coalition has misrepresented the current state of NHS spending. The currently chief executive of the English NHS, David Nicholson, recently called for politicians to be “completely transparent about the consequences of the financial settlements” for the NHS. Nicholson’s point perhaps was that, although politicians say the NHS has been protected financially, this was only relative to real cuts in other areas of government and, crucially, not in terms of the demands on healthcare.

A clue as to how Mr Stevens will run the NHS could be seen earlier this year when he co-authored a report for UHC arguing that the Obama administration could save $500bn in Medicare and Medicaid funding over the next 10 years by more aggressively coordinating medical care for pensioners and the poor. This pitch will have been very attractive to Sir Malcolm Grant. Mr Stevens said instead of concentrating on either cutting benefits or cuts to doctors and hospitals, the US healthcare debate should focus on a “third way”: cutting costs while improving care. A similar challenge awaits him at the NHS. However, the Keogh mortality report identified that safe staffing was a pivotal reason why NHS Trusts had failed un basic patient safety. Stevens is definitely unlikely to find a “third way” between balancing budgets to provide unsafe clinical staffing levels and adequate patient safety.

Some ministers have repeatedly praised Blair’s attempts to reform services, in the earlier period of their administration. In a speech to the Tory party conference earlier this month, Jeremy Hunt highlighted the efforts of Mr Blair and Mr Milburn to increase the use of the independent sector to reduce waiting times. However, Mr Stevens is also associated with the introduction of NHS targets, and helped create the key plan which brought them in. This NHS “target culture” which have been repeatedly attacked by the Coalition as playing a part in scandals such as that at Mid-Staffordshire, as a root cause of the ‘bully boy’ tactics (allegedly) by some NHS CEOs to achieve Foundation Trust and receive personal bonuses. Particularly important then for Labour is not where it has come from but where it is going to.

Andy Burnham MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Health, has repeatedly stated that a Labour Government will repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012) in its first Queen’s Speech in 2015. It has also been made clear that Labour will do this, even if Burnham is recruited laterally to a different job. For any corporate strategy, a number of drivers will be essential to remember: for example environment, socio-cultural, technological, legal and economics. With the appointment of Stevens “just in time” for the privateers – quite possibly, it is still remarkable that working out the legal niceties of working out ‘mission creep’ in the special administrator powers of NHS configurations is ‘work in progress’. Only this week, it was reported that the Royal Colleges of Physicians have genuine concerns about whether other amendments to the Care Bill are in the patients’ interest, pursuant to the current high-profile mess in Lewisham. Both Stevens and Grant are fully aware that they will have to deal with the political landscape, whatever that is, on May 8th 2015 and afterwards.

Strategic demands of the NHS

Currently NHS England has a number of powerful strategic demands, which could even appear at first blush inherently contradictory. For example, a purpose of patient safety management will be to minimise risk of harm to patients, whereas successful promotion of innovation can be achieved through encouraging risk taking in idea creation. Whatever Stevens’ ultimate vision – and this is why the implementation of Health and Social Care Act (2012) has been so cack-handed – it is essential that industry-acknowledged frameworks for change management are considered at the least. For example, in Kotler’s model of change management, the leader (Stevens) will not only have to ‘create a powerful vision’ but ‘communicate the vision well’.

Patient safety

There is no doubt that the Mid Staffs scandal was a very low point in the NHS. But there’s nothing like a good scandal for focusing the mind? In a general article in June 2009 by James O’Toole and Warren Bennis in the Harvard Business Review (“HBR”), the authors that no organisation could be honest with the public if it’s not honest with itself. This simple principle has been slow to come into the English law, though it has been introduced as an amendment in the Care Bill (2013). A notion has arisen that members of senior management turn a blind eye to failings deliberately (“wilful blindness“), but interestingly the authors draw on the work on Malcolm Gladwell. In his recent book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell had reviewed data from numerous airline accidents. Gladwell remarks, “The kinds of errors that cause plane crashes are invariably errors of teamwork and communication. One pilot knows something important and somehow doesn’t tell the other pilot.” The question is, necessarily, what a CEO can do about it. The authors propose two solutions inter alia. One is to “reward contrarians”, arguing that an organisation won’t innovate successfully if assumptions aren’t challenged. The authors advise organisations, to promote a ‘duty of candour’, to find colleagues who can help, who can be promoted, and who can be publicly thanked. The authors also advise finding some protection for whistleblowers: this might even include people because they created a culture of candour elsewhere. Initiatives such as the Nursing Times ‘Speak Out Safely’ are likely to be highly influential in catalysing a change, but a lot depends on the legal protection for whistleblowers given the current perceived inadequacies of the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998.

There is a growing realisation of implementation of patient initiatives has to be ‘top down’ as well as ‘bottom up’. For example, for Diane Cecchettini, president and CEO of MultiCare Health System, Tacoma, Washington, the key to patient safety has been achieved through leader engagement. She has developed an over-arching strategic framework for quality and safety that has served as the catalyst for the development of multi-year strategic quality and safety improvement plans throughout the MultiCare Health organisation.

Innovation

Innovation is another thorny subject. Innovation (and integration) is always going to be on a dangerous path if primarily introduced as an essential ‘cost cutting measure’, rather than bringing genuine value to the healthcare pathways. Nonetheless, the issue of financial sustainability of NHS England is a necessary consideration, even if the term ‘sustainability’ is open to abuse as I argued previously.

Innovation means different things to different people. As there is no single authoritative definition for innovation and its underlying concepts, including the management of innovation, any discussion on the topic becomes difficult and even meaningless unless the parties to the discussion agree on some common terminology. Innovation requires breaking away from old habits, developing new approaches, and implementing them successfully. It is an ongoing, collaborative process that needs considerable teamwork and skilled leadership. CEOs’ ability to lead their top management team successfully may provide the guidance and inspiration needed to support others to overcome obstacles and innovate. CEOs must provide effective leadership for top management teams to help organizations innovate.

It has been argued that, “There is no innovation without a supportive organisation”. Reviewed in the “International Journal of Organizational Innovation” by de Waal, Maritz, and Shieh (2010), innovation scholars have proposed numerous factors that, to a greater or lesser degree, have the potential to make organisations more conducive to innovation:

- A culture that encourages creative thinking, innovation, and risk-taking

- A culture that supports and guides intrapreneurial liberty and growing a supportive and interconnected innovation community

- Cross-functional teams that foster close collaboration among engineering, marketing, manufacturing and supply-chain functions

- An organisation structure that breaks down barriers to innovation (flat structure, less bureaucracy, fast decision-making, etc.)

- Managers at all levels that support innovation

- A reward system that reinforces innovative and entrepreneurial behaviour

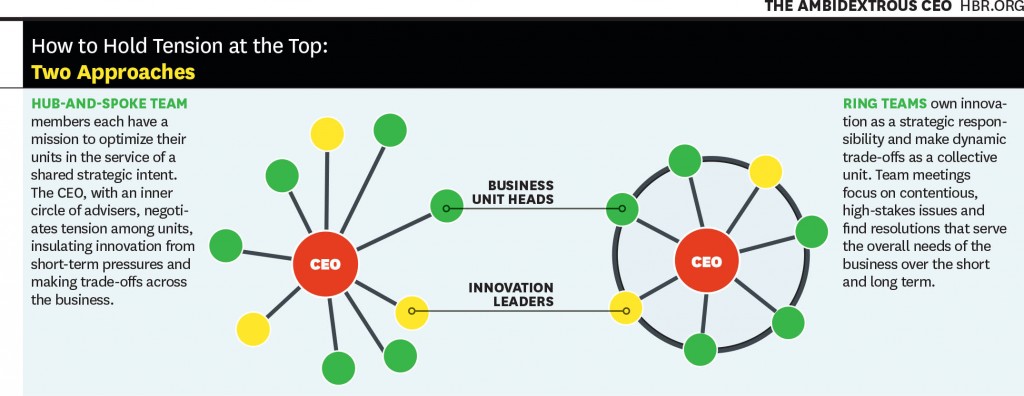

Communicating the vision, as described earlier, is also important for innovation management. This is a potential problem with KPMG’s Mark Britnell’s thesis of how raising the private income cap could promote innovation, as NHS and private wards nearly always co-exist in separate hospitals in ‘NHS Trusts’. It is argued in an interesting article in the Harvard Business Review (2011) entitled, “The ambidextrous CEO”, conflicts in innovation management are best resolved at the very top, and this could be filtered to the rest of the organisation through models such as “hub and spoke”.

It’s probably fair to say that a lot actually rests on the shoulders of CEOs in how innovative they wish their organisation to become. And certainly the ‘high-profile transfer of CEOs’, almost akin to the transfer of footballers, has attracted considerable recent interest, such as Burberry’s Angela Ahrendts joining Apple.

Thomas D. Kuczmarski in a rather sobering paper entitled, “What is innovation? The art of welcoming risk” identifies the CEO even as a potential ‘barrier-to-innovation’ (as far back as in 1996):

If you are like most CEOs, you are in a state of denial. Most CEOs express a fervent belief in new ideas and claim to be committed to innovation, but actions speak louder than words.

The truth is that most CEOs and senior managers are intimidated by innovation. Viewing it as a high-risk, high-cost endeavor, that promises uncertain returns, they are afraid to become advocates for innovation. However, because it clearly represents challenge and opportunity, most CEOs deny their reluctance to embrace innovation. They deny that their new product programs are underfunded or understaffed. They deny that they are closed to new ideas or ways of doing business. They deny that they fail to encourage or reward innovative thinking among their employees. Most of all, they deny that they have created within their organizations a fear of failure that stymies the urge to innovate.

All this denial is not good. It sends mixed messages throughout the organization and sets up the kind of second-guessing and playing politics that can undermine even the best developed business strategies. Unwilling to be measured by their failures, employees are reluctant to take risks that the successful development of new ideas demands and, as a result, even the desire to innovate diminishes.

Stevens (2010) himself has publicly expressed concerns on failure to innovate. For example, in the Harvard Business Review, he discussed how information on new clinical treatments spreads across the world quite fast, and how healthcare systems which fail to be flexible enough on picking up on this are likely to fail. Stevens’ example is striking:

However, the rate at which innovations are being translated into actual improvements is agonizingly slow — a frustrating problem that dates back to the world’s first controlled clinical trial in 1754. It proved that lemons prevented sailors from getting scurvy, but it then took another 41 years for a navy to act on the results. Wind the clock forward to today, and 15 years or so after e-mail became common, it turns out that most patients still can’t communicate with their doctors that way.

Deutsch (1973, 1980) proposed that how individuals consider their goals are related, very much affects their dynamics and outcomes. The basic premise of the theory is that the way goals are structured affects how people interact and the interaction pattern affects outcomes. Goals may be structured so that people promote the success of others, obstruct the success of others, or pursue their interest without regard for the success or failure of others. Deutsch identified these alternatives as cooperation, competition, and independence. In cooperation, people believe that as one person moves toward goal attainment, others move toward reaching their goals. They understand that others’ goal attainment helps them; they can be successful together. In competition, people, believing that one’s successful goal attainment makes others less likely to reach their goals, conclude that they are better off when others act ineffectively. When others are productive, they are less likely to succeed themselves. They pursue their interests at the expense of others. They want to ‘win’ and have the other ‘lose’. With independent goals, people believe that their effective actions have no impact on whether others succeed. Researchers have long debated whether cooperation or competition is more motivating and productive (Johnson, 2003). As regards the thrust of what happens in reality following 2015, therefore, the political landscape does very much happen. If Labour wish to promote collaboration perhaps through integration of health and social care, the entire nature of this dialogue will change. And the new CEO of NHS England will have a pivotal rôle in the organisational learning of the whole of NHS England.

Further implications for Labour in general policy

Some further issues are raised by Stevens (2010) short piece for the HBR. Labour has begun to ‘apologise’ for accelerating progress in the market of the NHS.

Introducing the ‘fair playing field’ of the market – another bogus concept which has gone badly wrong

The policy of ‘independent sector treatment centres’ under Labour has been much discussed elsewhere. PFI, although originally a policy which arose out of David Willett’s pamphlet for the Social Market Foundation (“The opportunities for private funding in the NHS“), and in the Major Conservative administration (see the work of Michael Queen), has seen various reformattings itself during successive Labour (Brown/Blair) and Conservative governments (Osborne/Cameron). The issue is that failing Trusts are not big to fail, unlike banks. Trusts ‘going bust’ are open to asset stripping from the private sector.

The opening up of the market is encapsulated in the document from Monitor, “A fair playing field for NHS patients”. Increasing the number of market providers not only potentially boosts ‘competition’ in the market, but also produces a supply of ‘predators’ in the terminology of Ed Miliband’s much maligned conference speech in Liverpool in 2011. This conference speech nevertheless successfully signposted with hindsight the highly celebrated political notion of ‘responsible capitalism‘. Many on the left now view the concept of ‘a fair playing field’ as being entirely bogus with the onset of decisions being made in the NHS on the basis of competition law not clinical priorities.

To what extent Burnham will wish to make a break from the past is the crux of the issue. Having signalled that he wishes to repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012) is the beginning of a long journey. At some stage, there will be a debate again about how much of the NHS is actually funded out of taxation, or whether, as anti-privatisation campaigners fear, whether we need to re-consider the explosive issue of co-payments or subsidiary payments. Burnham has signalled that he wishes to implement a NHS ‘preferred provider’ policy, in trying to capture lost ground on the increase in private provision in the NHS. But even here he may run into difficulty if legally the US-EU Free Trade Treaty, with discussions currently underway, make it impossible for him to implement such a policy.

But as it is, injecting ‘competition’ into the system could be in fact be the sort of competition which has dramatically failed in the energy sector. It is noteworthy that Ed Miliband has decided to whip himself up into a frenzy publicly about this in parliament, as part of the #costoflivingcrisis, rather than adopting the technocratic bureaucratic approach of waiting for the Competition Commission to investigate this particular market. It is well known that encouraging new entrants to the healthcare markets, even in the third sector, is fraught with difficulties, with the market occupied by a few well-known private sector brands. Here, the scandal of what are high prices, unlike ‘energy’, may remain a hidden scandal, as the customer is not directly the patient: it is the clinical commissioning group.

What do CCGs actually do?

Andy Burnham, to emphasise that he is not going to embark on yet another costly disorganisation in 2015, has explained that he intends to make the existing structures ‘do different things’. However, there is currently a bit of muddle as to what CCGs actually do.

Stevens states that:

Consolidation among care providers and barriers to entry for new hospitals mean that health-care delivery mostly relies on incumbents doing a bit better, as opposed to step changes in productivity from new entrants. Yet in the rest of the economy, new entrants unleash perhaps 20% to 40% of overall productivity advances.

Of course, with Stevens having leaving the NHS after ‘Blair times’, United Health has been set to become one of the beneficiaries of the advancing liberalisation of the NHS market.

It is now becoming more recognised that CCGs are in fact state aggregators of risk, or state insurance schemes. I had the opportunity recently of asking Sir Malcolm Grant in an exhibition at Olympia whether he had any disappointment that clinicians were not leading in CCGs as much as they could be, and of course he said “yes”. But strictly speaking GPs do not ‘need to’ lead CCGs as they are insurance schemes. The notion of ‘GP-led commissioning’ is widely felt to be a pup which was usefully actioned by the media to sell the controversial recent NHS reforms to a suspicious public.

This may or may not be what Stevens feels, albeit Stevens was speaking from the position of senior management in an aggressive US corporate at the time:

Increasingly, health plans should look to become ‘care system animators’ and not merely risk aggregators and transactional processors. Using their population health data, their information on clinical performance, their technology platforms, and their ability to structure consumer and provider-facing incentives, health plans have enormous potential to help improve health and the quality, appropriateness and efficiency of care. At UnitedHealth Group, our new Diabetes Health Plan, new telemedicine program, new eSync technology, and work on new models of primary care are all examples of what this can mean in practice.

Conclusion

In a perverse way, Stevens has an opportunity now to make the NHS work using knowledge of what the private sector does best and worst, in the same way that he was able to take advantage of his NHS policy knowledge while working for United Health. To what extent he will be concerned about the shareholder dividend of private companies as the NHS buggers on regardless will be more than an academic interest. No doubt the media will follow Stevens’ share interests with meticulous scrutiny.

The extent to which, however, he as the CEO can mould the culture of the NHS is an interesting one, however. If he (and ministers) believe that that it is he who should be leading change, then his default pathway will be one of private sector organisational change, with focus on patient safety and innovation through leadership. He will, however, run into problems if the NHS becomes primarily stakeholder-led. In other words, if patient campaigners continue to advocate that “patients come first“, especially through successful campaigning on patient safety or patient-led commissioning, Stevens might find his task is much harder than being a CEO of an American corporate.

Simon Stevens may seem like a powerful man. But there could be a man who is even more powerful from May 8th 2015, who might have a final say on many areas of policy, ahead of Stevens and Grant.

And that man is @andyburnhammp.

References

Birk, S. (2009) Creating a culture of safety: why CEOs hold the key to improved outcomes. Healthcare Executive (Mar/Apr), pp. 14-22.

de Waal G. A, Maritz P.A, Shieh C.J.(2010) Managing Innovation: A typology of theories and practice-based implications for New Zealand firms, The International Journal of Organizational Innovation 01/2010; 3(2):35-57.

Deutsch, M. (1973). The Resolution of Conflict. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Deutsch, M. (1980). ‘Fifty years of conflict’. In Festinger, L. (Ed.), Retrospections on Social Psychology. NewYork: Oxford University Press, 46–77.

Johnson, D. W. (2003). ‘Social interdependence: interrelationships among theory, research and

practice’. American Psychologist, 58, 934–45.

Kuczmarski, T.D. (1996) What is innovation? The art of welcoming risk, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 13(5), pp. 7-11.

Stevens, S. (2010) How Health Plans Can Accelerate Health Care Innovation, available at:

http://blogs.hbr.org/2010/05/how-health-plans-can-accelerate/

Toole, J.O., Bennis, W. (2009) What’s needed next: a culture of candor, Harvard Business Review, June edition, pp.54-61.

Tushman, M.L., Smith, W.K., Binns, A. (2011) The ambidextrous CEO, June, pp. 74-80.

Changing the narrative from “responsible capitalism” for the NHS

Nothing will last forever. For all the people who have spent the last few weeks attacking Andy Burnham or quoting misleading estimates of mortality rather than discussing the intricacies of patient safety, the discussion about the NHS within Labour will continue long after Andy has moved onto other things. The ethos of ‘responsible capitalism’ took root in Ed Miliband’s famous conference speech, and since then there have been countless examples in the corporate world to underline its importance. If the Health and Social Care Act (2012) did nothing for patient safety as a statutory instrument, though perhaps providing greater clarity on NHS failure regimens in the backdrop of reconfiguration, it certainly oiled the wheels for the trolley of corporatision of the NHS. Labour’s contribution to PFI has been extensively discussed elsewhere, but it is a material fact that Coopers and Lybrand were extolling the wonders of PFI long before a Labour government, from the time of Major’s think tank in 1995. In 2011, Ed Miliband called for long-term shareholders to have greater voting rights in takeovers, backed workers on company remuneration committees and said he wanted to break up unwarranted private sector monopolies in banking, energy and the media. The problem is that, in adopting an uncritical narrative of ‘responsible capitalism’ for the NHS, one is assuming the agenda of capitalism. Is this reasonable?

For Labour, it’s easy to do this. For people who wish to support Labour, like members of the Socialist Health Association, support can be lazy. John Maynard Keynes called capitalism ‘the astounding belief that the most wickedest of men will do the most wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone’. Mark Easton from the BBC has described that ‘responsible capitalism’ is an oxymoron, as “responsible” implies moral accountability while capitalism is driven by self-interest. A cornerstone of socialism is Marx’s philosophy of economic determinism, which identifies prevailing economic conditions as the motivating force behind all political and social activity. This materialistic worldview, is now deeply ingrained in American social, political, and religious philosophy, and attributes much human behaviour to the economic environment. This indeed paradoxically for libertarians thus frees man of personal responsibility for his own behaviour, and enslaves the individual to the free market. Neoliberalism, like socialism, in extreme can easily be argued as toxic.

Whilst Ed Miliband is doing political foreplay with the capitalist world, it could be a case of unrequited love. This takes on a Shakespearean dimension of tragedy, when you consider that Ed Miliband appears to have shunned his ‘socialist girlfriend’. While it’s Ed Miliband’s comments on Google and tax avoidance that will inevitably attract the most media attention, by far the more interesting section, perhaps, of his speech at the company’s “Big Tent” event at The Grove hotel in Hertfordshire was on capitalism and socialism. The Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt rejected the idea put forward by Labour leader Ed Miliband that the search giant should practise “responsible capitalism”, arguing the company simply follows international tax laws – which he described as “irrational”. This problem for Labour, now relevant to how much of the NHS should be re-allocated into private hands, therefore introduces the concept of “responsible socialism”. In a reference to Labour’s old clause IV, which called for “common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange”, Miliband added that “It wasn’t just my dad who thought it, of course. Until 1995 this view was enshrined on the membership card of the party I now lead.” However, “red baiting” — the process of referring to one’s opponents as “socialists,” and relying on that word alone to silence opposition — remains one of the oldest tricks in the Tories’ “rulebook”. Ideological opponents to socialism often use the term “socialist” to refer to any increase in government power. That is arguably, not strictly speaking, historically accurate. “Socialism” is not a direction. Historically, socialism has only one meaning: a system in which the state — or the workers directly — own the means of production.

It is said socialism may have emerged from a discontent with what remained of the feudal state after the French Revolution of 1789, and with the emergent, eminently abusive nature of pure laissez faire industry. For the peasant and working classes, there was a sense that real change had been within grasp at the turn of the 18th century. Marx developed a theory whose purpose, in part, to embrace this frustration and lessons from other jurisdictions: socialism — which Marx regarded as a means to an end — was a hybrid capitalist/Communist system, in which the means of production were publicly owned, but working and bourgeoisie classes remained separate, and therefore, to Marx, impermissibly unequal. It can be argued that some politicians, like Nixon and LaGuardia, took deliberate and permanent possession of private property, for the collective benefit of their constituents, and yet neither modern America nor New York City can fairly be called socialist. Whatever socialism might be, it is not straight-forward. However, it is perhaps time to start stop trying to scare floating voters with “the spectre of Communism” and, as a nation, finally make peace with the fact that United Kingdom, like the United States, is not, nor has it been for some time, a pure laissez faire nation, because fundamentally the public will not accept it. Socialism, like all political philosophies is a complicated and diverse ideology. It has like all ideologies its pros and cons. It has its tradeoffs. Yet, like all political philosophies, it needs to address actively its downsides to be at its best. People do not dare mention that S word. They prefer the other S word: “Social” (and “D” for Democratic).

It is therefore time to change the narrative away from ‘responsible capitalism’ and to contemplate an approach of ‘responsible socialism’ as well, perhaps? The irony of NHS England is that it is the biggest QUANGO in the land, but the possible advantage is that it could implement a coherent public health policy genuinely for the ‘health of the nation’. Responsible socialism, whilst felt as a tautology by some and an oxymoron by others, potentially can dispose of irrelevant, meaningless pseudo-choice, and eliminate the unnecessary transaction costs in waste and inefficiency injected by a free market. Critical friends of Labour can do no more better than to think about innovative ways of standing up for what they believe in. This will ultimately, I feel, earn more respect from the senior echelons in Labour. While Ed Miliband may be ‘right’ about ‘responsible capitalism’, there are so many bandwagons we can all jump on, and taking about responsible capitalism in the NHS might suggest we have given up on socialism for good.

Reconfigurations and reconsultations: when is a consultation on the NHS actually legally “fair”?

What this article is not about

Last week, the “Save Lewisham A & E” (@SaveLewishamAE) campaign finally arrived at Court 76 of the Royal Courts of London in the Strand. I should like to give an overview of some of the background issues of this area of law, known as “public law”. To read an account of it, you might like to refer to this brief article on the BBC website.

Reconfiguration in the NHS: a need to revisit LeGrand’s chess pieces?

All of this which is the NHS is doing seems to be like one giant 3D game of chess where it is difficult to see all of the pieces. The imposition of the market on the NHS, and the game of chess, is of course a topic more than familiar to Prof Julian LeGrand.

Legrand’s seminal article can be viewed here.

The policy background

Reconfiguration is in fact a highly significant issue in social policy. For example, in a very thought-provoking article entitled, “Publics and markets: What’s wrong with Neoliberalism?”, Clive Barnett from the Faculty of Social Sciences at the Open University writes that:

“Thinking seriously about the political rationalities of liberal governmentality should lead to the recognition of how assumptions about motivation and agency help shape public policy and institutional design. For example, market-reforms in social policy in the UK have been partly driven by fiscal pressures dictated by ‘neoliberal’ macroeconomic policies. However, just as important “was a fundamental shift in policy-makers’ perceptions concerning motivation and agency” (LeGrand 2006). LeGrand suggests a stylized (sic) distinction between two models of motivation and two models of agency.

- If it assumed that people are wholly motivated by self-interest, they are thought of as knaves; if they are thought of as motivated by public-spirited altruism, they are knights.

- If it assumed that people have little or no capacity for independent action, then they are thought of as pawns; if they are treated as active agents, they are thought of as queens.

This distinction helps to throw light upon how institutional reconfigurations of welfare are shaped by changing assumptions about how state agencies function, how officials are motivated, how far people are agents, and in particular how agential capacities of recipients can be mobilised to make public officials more knight-like. LeGrand characterizes the post-1979 period of social policy in the UK as ‘the triumph of the knaves’. It involved two related shifts: towards an empirical assumption about the knavish tendencies of professionals working in public administration; and towards a normative assumption that users should be treated more like queens than pawns. The preference for ‘market’ reforms follows from these two assumptions: “if it is believed that workers are primarily knaves and that consumers ought to be king”, then it follows that “the market is the way in which the pursuit of self- interest by providers can be corralled to serve the interests of consumers” (ibid. 9).”

This suggests that the distinction between Keynsian social democracy and neoliberalism is simply a difference between abstract, substantive principles: egalitarianism (and the state as a vehicle of social justice), versus liberty (and the state as a threat to this). Just as significant is a practical difference between two sets of beliefs about motivation and agency (ibid, 12). ‘Neoliberals’ tend to think of motivation in terms of self-interest and egoism, ‘social democrats’ in terms of knights and altruism. And ‘neoliberals’ tend to presume a capacity for autonomous action, whereas ‘social democrats’ presume this capacity is conditioned and therefore can be justifiably cultivated by state action.

The Handbook of Social Geography, edited by Susan Smith, Sallie Marston, Rachel Pain, and John Paul Jones III. London and New York: Sage

Only time will tell whether this approach is fundamentally flawed.

The English law

Where does any legitimate expectation arise from and do they exist in English law?

Consultation with those likely to be affected by a decision increases the transparency of the process. By allowing engagement in the decision-making process, it may lessen the blow for those affected by the decision that is ultimately taken. Legitimate expectations are very important in the English law. Prior to Coughlan, it was unclear “whether substantive legitimate expectations were recognised within UK law”. In order to understand the issues surrounding legitimate expectations, it is useful to consider the actual details of “Coughlan”, R v. North and East Devon Health Authority ex parte Coughlan (2001) QB 213. The claimant, Miss Coughlan, was a quadriplegic who lived in a hospital for the chronically disabled from 1971-1993 called Newcourt hospital. Newcourt hospital was deemed to be unacceptable for modern care and as a result, she was moved to a new, purpose built facility in 1993 called Mardon House that was specifically designed to accommodate severely disabled patients. Miss Coughlan and other residents in the new facility were given an explicit “promise that they could live there ‘for as long as they chose’ whereby it would be their “home for life”. The evaluation in Coughlan primarily hinged upon the Health authority’s promise in providing a ‘home for life’ to the claimant.

Woolf MR stated (at paragraph 57):

“Where the Court considers that a lawful promise or practice has induced a legitimate expectation of a benefit which is substantive, not simply procedural, authority now establishes that here too the Court will in a proper case decide whether to frustrate the expectation is so unfair that to take a new and different course will amount to an abuse of power. Here, once the legitimacy of the expectation is established, the Court will have the task of weighing the requirements of fairness against any overriding interest relied upon for the change of policy.”

And what about the actual law? R v. Inland Revenue Commissioners ex parte MFK Underwriting Agents Limited (1991) WLR 1545 in which Bingham LJ and Judge J stated that, for a statement to give rise to a legitimate expectation, it must be:

“clear, unambiguous and devoid of relevant qualification” (para. 1570)

The promise has to be made by the decision maker: R (on the application of Bloggs) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2003] EWCA Civ 686, [2003] 1 WLR 2724. Further the promise must be made by someone with actual, or ostensible, authority, otherwise the decision will be ultra vires: South Buckinghamshire DC v Flanaghan [2002] EWCA Civ 690, [2002] 1 WLR 2601. Where a promise is contained in a policy of general application it is not necessary for the applicant to show that he knew of the policy provided he fell within the policy’s general scope, R v Secretary of State for the Home Department ex parte Zeqiri [2002] UKHL 3. Detrimental reliance by the applicant is not an essential prerequisite but it may affect the weight that is to be given to the legitimate expectation.

Is there a need for a consultation at all?

Whether or not there is in law an obligation to consult, where consultation is embarked upon it must be carried out fairly. What is ‘fair’ will obviously depend on the circumstances of the case and the nature of the proposals under consideration: see R (Edwards) v Environment Agency [2006] EWCA Civ 877 per Auld LJ at [90]. This rather open-ended doctrine of fairness means that different judges could reach different views on the lawfulness of the consultation process on the same facts. This raises the possibility that the underlying merits of the decision in question could (even sub-consciously) influence the outcome of any challenge. the decision-maker will usually have a broad discretion as to how a consultation exercise should be carried out (see R (Greenpeace) v. Secretary of State for Trade & Industry [2007] EWHC 311 (Admin) at [62] per Sullivan J); and what should be consulted upon (see The Vale of Glamorgan v. The Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice [2011] EWHC 1532 (Admin) at [25]).

How should the consultation take place?

The decision-maker’s discretion cannot unbounded, however, as it is commonly accepted that certain fundamental propositions must be adhered to. These propositions are known as the Gunning (or Sedley) principles, having been propounded by Mr. Stephen Sedley QC and adopted by Mr. Justice Hodgson in R v. Brent London Borough Council, ex parte Gunning (1985) 84 LGR 168 at 169. They were subsequently approved by Simon Brown LJ in R v. Devon County Council, ex parte Baker [1995] 1 All.E.R. 73 at 91g-j; and by the Court of Appeal in R v. North and East Devon Health Authority, ex parte Coughlan [2001] QB 213 at [108].

The Gunning principles are that:

- the consultation must take place when the proposal is still at a formative stage;

- sufficient reasons must be put forward for the proposal to allow for intelligent consideration and response;

- adequate time must be given for consideration and response; and

- the product of consultation must be conscientiously taken into account.

The English law provides that the actual responses of consultation must be conscientiously considered. This ties in with the first Gunning principle which is really a proxy for whether the decision-maker has made up its mind. If the decision-maker does not properly consider the material produced by the consultation, then it can be accused of having made up its mind; or of failing to take into account a relevant consideration.

Where there are large numbers of individuals who are affected, it may be appropriate to consult with their representatives (e.g. trade unions, or professional bodies). In British Medical Association v. Secretary of State for Health [2008] EWHC 599 (Admin), for instance, a case concerning changes to doctors’ pensions, Mitting J. held that it was sufficient to discharge the consultation obligation for the Minister to have engaged in correspondence with doctors’ leaders. The Court did not say that there needed to be consultation with individual doctors themselves.

Is there ever a need for a re-consultation?

A decision-maker is faced with a conundrum where it has genuinely considered consultation responses and wants to adjust its original proposals, or where circumstances have changed since consultation began. Is the decision-maker required to consult again? This precise issue was discussed by Silber J. in R (on the application of Smith) v East Kent Hospital NHS Trust and another [2002] EWHC 2640 (Admin), [2002] EWHC 2640. Silber J. observed that ‘trivial changes do not require further consideration’ (at [43]). The learned judge was mindful of ‘the dangers and consequence of too readily requiring re-consultation’, noting that in R v. Shropshire Health Authority and Secretary of State ex parte Duffus [1990] 1 Med L R 119, Schiemann J (with whom Lloyd LJ agreed) had stated that:

‘Each consultation process if it produces any changes has the potential to give rise to an expectation in others, that they will be consulted about any changes. If the courts are to be too liberal in the use of their power of judicial review to compel consultation on any change, there is a danger that the process will prevent any change — either in the sense that the authority will be disinclined to make any change because of the repeated consultation process which this might engender, or in the sense that no decision gets taken because consultation never comes to an end. One must not forget there are those with legitimate expectations that decisions will be taken’.

Silber J. concluded that fresh consultation was only required where there was ‘a fundamental difference between the proposals consulted on and those which the consulting party subsequently wishes to adopt’. What then is ‘fundamental’? In R (Elphinstone) v Westminster City Council, [2008] EWHC 1287 (Admin) at [62], Kenneth Parker QC observed that ‘a fundamental change is a change of such a kind that it would be conspicuously unfair for the decision-maker to proceed without having given consultees a further opportunity to make representations about the proposal as so changed.’

Where the Court finds that the consultation process was unfair (or non-existent) it will be in rare cases that the decision-maker will be able to persuade a Court that consultation would have made ‘no difference’. In most cases, a failure to consult fairly will result in the quashing of the underlying decision. In Shoesmith v. Secretary of State for Education [2011] EWCA Civ 852, the Court of Appeal expressed great reluctance to give weight to the ‘no difference’ principle in a case where one might have thought that the decision would inevitably have been the same whatever opportunity to make representations had been provided to the claimant.

In considering the fairness of the consultation, Silber J. held that the council had to comply with the ‘Sedley principles’, and also with the observations of Lord Mustill in R v. Secretary of State, ex parte Doody [1994] 1 AC 531, 550 that ‘Since the person affected cannot make worthwhile representations without knowing what factors may weigh against his interests fairness will very often require that he is informed of the gist of the case which he has to answer’3.

Silber J. held, with respect to the second of the Sedley formulation that:

“It is important that any consultee should be aware of the basis on which a proposal put forward for the basis of consultation has been considered and will thereafter be considered by the decision-maker as otherwise the consultee would be unable to give, in Lord Woolf’s words in Coughlan, either “intelligent consideration” to the proposals or to make an “intelligent response” to it. This requirement means that the person consulted was entitled to be informed or had to be made aware of what criterion would be adopted by the decisionmaker and what factors would be considered decisive or of substantial importance by the decision-maker in making his decision at the end of the consultation process.

I do not think that a consultee would not have been properly consulted if he ought reasonably to have known the criterion, which the decision-maker would adopt or the factors, which would be considered decisive by the decision-maker but that the only reason why the consultee did not know these matters was because, for example, he had turned a blind eye to something of which he ought reasonably to have been aware. Thus, consultation will only be regarded as unfair if the consultee either did not know the criterion to be adopted by the decision-maker or ought not reasonably to have known of this criterion. Of course, what a consultee ought reasonably to have known about the factors, which will be considered decisive by the decision-maker depends on all the relevant circumstances, which may well be different in each case.” [46] – [47]

Conclusion

On the last day of the Lewisham hearing in the High Court, the following was announced, as mentioned on the “Save Lewisham Hospital Campaign: legal challenge” webpage:

“A dramatic back-drop was NHS London’s announcement – strangely coinciding with the final day of our challenge – that they intend to close 9 A&Es from London’s 29 current A&Es over the next 5-6 years.”

The problem about reconfiguration is the “domino effect”, and for all the talk about autonomous units in the NHS, it is clear that this policy is volatile, unstable, and clearly a challenge for people in the community as well as the judiciary. The Lewisham Campaign could just be the tip of the iceberg, as leading QCs and their staff continue to deliberate over whether existant policies imposed by Statute and by the Department of Health are clear and unambigious enough, and whether the Secretary of State is entitled to feel that he has met any tests he has set himself about consultations. From the case law, it will seem that the validity of any consultation will depend on the extent to which the respondents knew about the ambit of the consultation, and it seems that the Court is very keen to hear from those affected by decisions which are made in their name.

GPs “as businessmen”: from ‘Ready Mix Concrete’ to the NHS

This article is not peer-reviewed. You are advised to read this article in bits, according to which parts interest you. If you would like to engage constructively in some of the issues here, I can easily be reached on my twitter thread @legalaware_coys.

Part of the strategy employed by agents in the media in convincing the general public that a new privatised NHS is not vastly different from the NHS prior to 1 April 2013 has been to emphasise that GPs have “always been businessmen”. GPs are, however, clearly not businessmen in that you don’t see adverts for them on Google or the internet at large. They do not, as yet, spend time advertising in local newspapers or other media, such as local radio. It is a dangerous proposition, however, to suggest that they are businessmen rather than primarily professional clinicians, who are concerned more about how they can minimise spending in their budget, or how they could make a surplus. They are not, as such, directly selling anything to patients.

I asked Dr David Wrigley (@DavidGWrigley) about this media curiosity of ‘GPs as businessmen’. David replied to me as follows,

“Hi Shibley, It comes up all the time. In public debates I have had with MPs and radio/TV interviews it is a question that is always levelled at GPs. Usually it is from those who are keen to promote private sector encroachment onto the NHS. I always say GPs are totally different to the private sector. We work in a community for a whole career and invest in the local people and the practice. We are self employed and make an income from the NHS but we don’t move on when the going gets tough – as the private sector do. The breast PIP scandal shows what the private sector does when the profits dry up – they move on and wash their hands of the patients and leave the NHS to pick up the pieces.I try and keep getting the message across and hope you can help to do so too!”

Looking at the precise legal status of a GP is possibly more productive. Self-employed GPs have been held to be “workers” for the purposes of the Employments Right Act (1996). It had been widely reported that the term that “GP-led companies” is a myth (for example here). The issue is that self-employed GPs are not individually operating as as private limited companies; if they were, they would have shareholders and be obligated as directors to ensure success of the company, and generate a profit consistent with the Companies Act (2006). In the absence even of any formal agreement, they can indeed be a traditional partnership, but a traditional partnership lacks limited liability (link here).

“It seems likely that the medical profession is set for a more federated future and smaller practices in particular may wish to explore opportunities to either merge with other practices or to enter into co-operative or federated arrangements to bring together specialist expertise, share overhead resources and take advantage of economies of scale without totally sacrificing their autonomy. The demands on general practice look set to increase as the trend for care is transferred from hospital to the community. Simultaneously, the increasing commercialisation of the medical profession is likely to inspire more dynamic management structures and possibly greater separation of healthcare provision and management. Opportunities will arise for all natures of practice, but it will be down to each individual practice to harness those which will allow them to reap the greatest benefits for their business and patients. In this environment, investing time to consider the optimum form of legal entity to take forward a practice is crucial and well worth making. “

The trickiest situation currently, in working out the employment status of a GP, is in the GP working under an out-of-hours contract. Such a GP had his claim ‘struck out’ for not being an employee ab initio (link here):

“An out-of-hours general practitioner (GP) who argued that he was victimised for making a public interest disclosure (PID) has had his compensation claim ruled out by the Employment Appeal Tribunal (EAT) on the basis that he was in business on his own account and was neither a worker nor an employee within the meaning of the Employment Rights Act 1996.”

The explanation is very interesting:

“In ruling that his role within the charity did not bring him within the definition of worker or employee under the act, the EAT noted that he also worked for other out-of-hours services, took responsibility for his own tax and national insurance matters and had entered into an agreement with the charity which stated unequivocally that he was self-employed.

The GP contended that he had an overarching contract with the charity and was employed during each separate shift he worked. However, the EAT accepted the charity’s arguments that practitioners on its books were under no obligation to work shifts and that it was not obliged to offer work to any particular GP. Concluding that the GP ‘was in business on his own account’, the EAT ruled that the charity had insufficient control over his work and there was insufficient mutuality of obligation to give rise to an employment relationship.”

“Mutuality of obligations” is all about whether there an obligation on the company to provide work and for the individual to perform work when given it; if this mutuality is not present, an employment relationship will not exist. Traditionally it has been held that if an individual were entitled to send a substitute to perform his duties, this would usually be enough to demonstrate that the contract is not a contract of employment. In “Ready-Mixed Concrete” (case description here), the claimant drove a concrete mixing lorry for the respondent. He had to drive the lorry exclusively for the respondent, he wore the respondent’s uniform and he agreed to submit to all reasonable orders ‘as if he were an employee’. Notwithstanding this, it was held that he was an independent contractor and not an employee. One of the critical features was that he was not required to drive the lorry personally. He could employ a substitute driver to do so. [Note that this lack of personal service would also mean that he would not be held to be a worker under the worker definition.]

The unfortunate description of “GP as businessmen”, arguably encourages the public to consider that they are driven by profit. This is a problem, when you add in three further strands of argument.

- Firstly, that the NHS is able to make £2.4 bn “surplus”, but this is not put in back into frontline care by the Treasury, but is used to ‘balance the books’ for an ever-worsening UK economy.

- Secondly, it has been widely reported that there are GPs on “clinical commissioning groups”, and there are concerns about conflicts-of-interest where the commissioner and commissioned might be one-in-the-same (link here).

- Thirdly, the introduction of CCGs has not made doctors feel more involved in commissioning decisions, a new survey has revealed (link here). Research by Pulse magazine found that out of 303 doctors questioned more than half (55%) said they do not feel any more involved in commissioning services now than they did under PCTs. Only 36% of GPs surveyed said the introduction of CCGs had made them feel more involved in commissioning decisions.

The argument that “GPs have always been businessmen”, mainly advanced by people who are in favour of the “Reforms”, is extremely harmful potentially to the reputation of healthcare professionals, as the General Medical Council’s own code of conduct ‘Duties of a Doctor’ makes it very clear that: “You must make the care of your patient your first concern“. Any suggestion that this priority is displaced threatens to undermine the very heart of the doctor-patient relationship, and this could be very destructive for the new privatised NHS, if left unchallenged.

“Voters back private care in the NHS”: but so soon after Winterbourne?

The extent of the evidence-based, peer-reviewed, rôle of ‘competition’ in the National Health Service is limited. It necessarily has to be taken with caution, and findings should not be inferred lightly.

“Presented with the statement, “It shouldn’t matter whether hospitals or surgeries are run by the government, not-for-profit organisations or the private sector, provided that everyone including the least well-off has access to care”, 83% agreed while only 14% disagreed. Of those, more than half – 56% – said they agreed strongly. Just 10% said they disagreed strongly.

In addition, only a minority of voters think the NHS provides better care than systems in France and Germany which have forms of universal social insurance with higher proportions of private provision.

Asked what they thought of the idea, “People living in European countries such as France and Germany don’t receive as good a level of healthcare as we do on the NHS,” only 36% agreed. More people – 41% – disagreed. Another 23% said they did not know. Still a small majority of the population think that the NHS is “the envy of the world”, however, by 56% to 38%.

David Green, Director of Civitas, said: “It is clear that most people still support the NHS, but that does not mean they are opposed to change.

“What this poll shows is that people generally support the idea of universal care at the point of need – not the virtual state monopoly of healthcare provision that we currently see.

“Despite the apparent fears of ministers, most people would be happy to see greater diversity of provision, which would help increase efficiency and drive up standards by enhancing competition.

“The best way to raise standards and look after patient interests is to promote pluralism so that rival providers are compelled raise their game. We all know as consumers that, unless we have alternatives, producer interests come to dominate.”

This is interesting from a management perspective, if only because extremely bad healthcare can occur in both the private and public systems. This was only written recently about the “Winterbourne Care Home Scandal” on 9 August 2012:

“As the reformed health service prepares for more competition and increased use of the private sector, there are important lessons for commissioners. The serious case review says that on paper Castlebeck’s policies, procedures, operational practices and clinical governance were impressive. Yet the reality of the way patients were assessed and cared for, how staff were recruited, trained, managed, led and disciplined, how complaints were handled and how records were kept came down to “arbitrary violence and abuses”.

This does not mean, of course, that such practices are in any way representative of the private sector, and rotten cultures take root in the public sector as well. But the chasm between what Castlebeck promised and the reality means that commissioners had clearly failed to test the foundations of those claims at the outset or use them as a rigorous benchmark for monitoring performance.

A similar question arises in the commissioning of NHS services. They are more open to scrutiny and evaluation, but failure still happens.

The purchaser/provider split is intended to promote quality, drive up standards and ensure the interests of the patient are championed. But the scandal at Winterbourne View hospital demonstrates how far commissioning still has to travel before it meets its objective.”

Bad practice can occur in both the private and public sector, and when it occurs it is a tragedy for all. The irony is, of course, that it has been a stated intention of policy-makers in healthcare to “import” the best practices from the private sector, such as efficiency and productivity. Experience from the privatised utilities is not one of a market approaching perfect competition. Far from it. There are few suppliers, meaning that the bargaining power of suppliers compared to customers is huge, and there is poor ‘competitive rivalry’ as it is in the best interests of these companies in different sectors including electricity, gas, water and telecoms to keep prices relatively high and return maximum shareholder dividend. The justification for keeping these prices high is to ‘return investment’ into the infrastructure of these sectors, but this argument is much harder to pull off in the NHS, where some of the infrastructure in the NHS is being abolished (which includes national institutions such as the National Patient Safety Agency, the Health Protection Agency, or the NHS Institute for Innovation and Change), and there needs to be funding for the training of doctors, nurses and all other health care professionals. Even the most ardent critics of the NHS have difficulty in explaining how the expensive £3bn undemocratic change will improve patient safety, particularly since the market will end up being much more fragmented (as has been, for example, the experience of the privatised railways industry in England.) Therefore the press release is carefully worded, “Voters back private care in the NHS”, rather than “Voters back privatisation in the NHS”. When the question is worded in the latter version, the outcome is rather different, as demonstrated by 38 degrees. 354155 signatures have been recorded to date (link here).

It is particularly interesting that the Civitas press release contains this attack on the ethos the NHS:

“If the Mid-Staffs scandal is not to be simply the latest in a series of outrages, the government must wake up to the need for reform. The Francis report has shown that the current command-and-control regime does not guarantee a public-service ethos in the NHS.”