Home » Labour (Page 3)

Can English health policy be advanced through signing petitions?

Today, the intensity of opinions of some parliamentarians in spitting bullets at 38 degrees was incredible.

In case you’ve missed what they were talking about, here it is.

Here was the first blast at ’38 degrees’.

Paul Burstow:I start by acknowledging the receipt of a petition handed to me yesterday, containing 159,000 signatures collected by members of 38 Degrees, expressing their concerns about the matter we are debating today. I know that a great many Members will have received e-mails about that and will have their own opinions, and I want to discuss the issues.David T. C. Davies:Will the right hon. Gentleman refresh my memory? Is that the same pressure group that a few years ago was saying that the NHS was going to be privatised, which is completely untrue, and which a couple of months ago was saying that it was about to be silenced by some Bill the Government were pushing through yet is now very noisily campaigning once again? Surely this cannot be the same completely unreliable group of left-wingers with links to the Labour party, can it?

And then there was more.

I listened with great interest to my hon. Friend the Member for Enfield North (Nick de Bois) but I will be supporting the Government 100% tonight because I have great confidence in what the Government have achieved with the NHS. I say that because I have seen the alternative; I have seen what has happened to the NHS when it is run by Labour, because that is the problem that I and many of my constituents face at the moment in Wales.

My right hon. Friend the Member for Sutton and Cheam (Paul Burstow) came forward earlier with a petition from the left-wing pressure group 38 Degrees. Health campaigners today have been talking today about the amount of salt that we take but one has to take dangerously large pinches of salt with anything that comes out of that organisation. These people purport to be a happy-go-lucky students. They are always on first name terms; Ben and Fred and Rebecca and Sarah and the rest of it. The reality is that it is a hard-nosed left-wing Labour-supporting organisation with links to some very wealthy upper middle-class socialists, despite the pretence that it likes to give out.

It is 38 Degrees who were coming out with all sorts of hysterical scare stories a few years ago about how the Government were going to privatise the NHS. It took out adverts in newspapers, scaring people witless that that was going to happen. Of course the organisation has forgotten all about it now because there was never any intention to do that. We will never privatise the NHS because we believe in public services in this party. A couple of months ago, 38 Degrees came out with more scare stories about how it was going to be gagged because of another piece of legislation that the Government were putting through to bring about fairness in elections. It said that we would never hear from it again, and yet here we are a few months later with yet another host of terrible stories, scaring members of the public quite unnecessarily. I do not think that we have to take any lessons from 38 Degrees, nor hear any more about their petition.

But are petitions are good thing?

Critics of petitions say that petitions are too easy to organise because of the automated nature of mailing lists these days. Because of the ease in producing a petition, it can be easy to inundate people with many petitions, thus making it difficult to work out which are the genuine causes.

Consequently, due to ease of producing petitions, some feel that the volumes of signatures need to be massive before any impact is made.

And even if petitions have a large number of signatories, it can be the case that their effects are short-lived. After amassing many signatures for months for the #WOWpetition, the parliamentary debate was barely covered in the media; and there appeared to be little consequence from it.

Likewise, there was little coverage of the clause 119 debate on the BBC News 24 ‘rolling news’ service. Nonetheless, it did manage to surface as a web news story on the BBC News website.

The frustration for members of the general public is that many parliamentarians don’t appear to be listening.

There’s an inevitability about votes in parliament, where the arithmetic means that votes can be won completely divorced from the quality of the debate.

And parts of the debate were bad. Dr Dan Poulter’s debating content was incoherent, badly structured and full of ectopic odd partisan point-scoring. The style was vulgar and offensive, like a junior doctor presenting a garbled and incoherent history within the constraints of a long medical ward round.

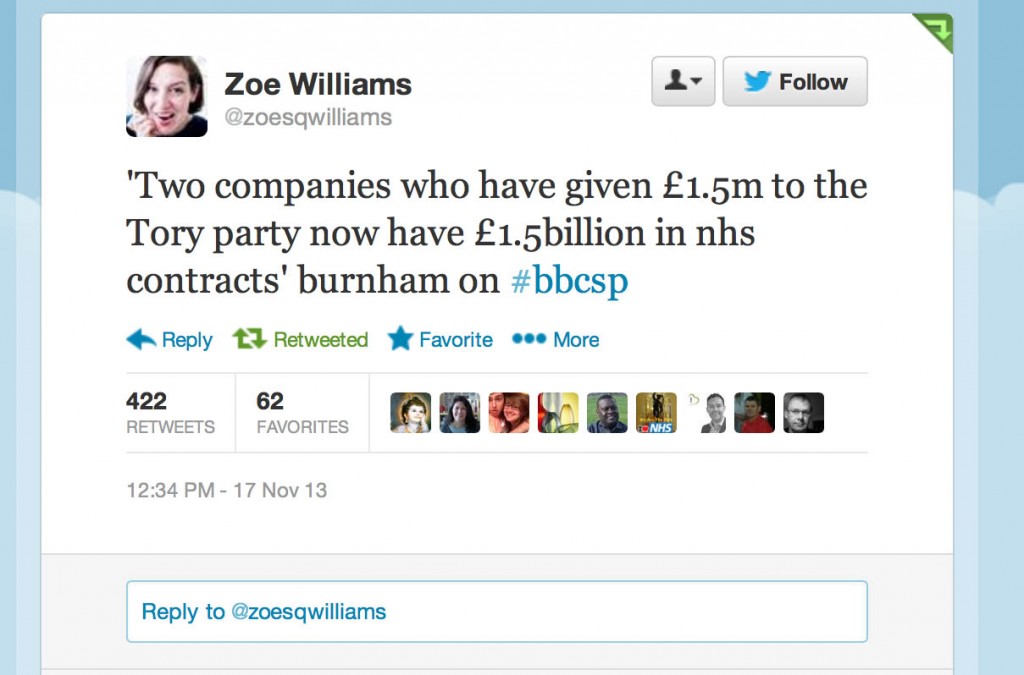

Many Labour MPs, not least the Shadow Secretary of State for Health Andy Burnham MP, were clearly more than mildly irritated at the grotesque depiction of the clause 119 policy as a natural extension of Labour’s policy.

Grahame Morris, MP for Easington, made as ever excellent comments. Along with Andrew George MP, he is on the influential Health Select Committee. And yet Morris was given rather odd replies by Simon Burns MP and Stephen Dorrell MP, head of the said committee, which did not take the debate much further.

Burstow, a Liberal Democrat who is likely to lose his seat in 2015, produced an amendment and withdrew it. But being bought off (not literally) to chair a committee is apparently not uncommonplace for shennanigans such as these.

Jeremy Hunt MP in summing up used the term ‘whole person care’ which could be an unconscious display of waving the white flag when he could have simply said ‘integrated care’.

Throwing forward, it could be that clause 119 in some form could be just what the Dr ordered to facilitate the future reconfigurations necessary for implementation of integrated care in some form.

Patently Dorrell wishes to avoid the term ‘integrated care’, in calling it ‘joined up care’, to avoid any breach of EU competition law.

It’s trite to mention it, but the only petition that really counts is the General Election.

I received a direct message from somebody today to say ‘I am fucking fuming’.

He then asked, “Should I vote Labour or NHA Party?”

As they say – “the choice is yours”.

‘Whole person care’ needs a bit of tinkering and strong leadership

In a now very famous article, “The genius of a tinkerer: the secret of innovation is combining odds and ends”, Steve Johnson describes how innovation must be allowed to succeed in face of regulatory barriers.

“The premise that innovation prospers when ideas can serendipitously connect and recombine with other ideas may seem logical enough, but the strange fact is that a great deal of the past two centuries of legal and folk wisdom about innovation has pursued the exact opposite argument, building walls between ideas”

“Ironically, those walls have been erected with the explicit aim of encouraging innovation. They go by many names: intellectual property, trade secrets, proprietary technology, top-secret R&D labs. But they share a founding assumption: that in the long run, innovation will increase if you put restrictions on the spread of new ideas, because those restrictions will allow the creators to collect large financial rewards from their inventions. And those rewards will then attract other innovators to follow in their path.”

Bundling of goods can offend competition law, so that’s why legislators in a number of jurisdictions are nervous about ‘integrated care’.

In the past, Microsoft has accused of abusing Windows’ dominant status in the desktop operating system market to give Internet Explorer a major advantage in the browser wars.

Microsoft argued bundling Internet Explorer with Windows was just innovation, and it was no longer meaningful to think of Internet Explorer and Windows as separate things, but European authorities disagreed.

There’s no doubt that ultimately ‘whole person care’ will be some form of “person centred care”, where the healthcare needs (as per medical and psychiatric domains currently) are met.

But it is this idea of treating every person as an individual, with a focus on his or her needs in relation to the rest of the community which is the most challenging aspect of whole person care.

Joining up medical and social care with an ‘unified care record’ has never been attempted nationally, but it makes intuitive sense that care information from one institution should be made available to another.

Far too many investigations are needlessly repeated on successive admissions of the same patient, which is exhausting for the person involved. It would make far more sense to have a bank of results of investigations for persons, say who are frail, who are at risk of repeated admissions to acute hospitals in this country.

And this can’t be brought in with the usual haphazard ‘there is no alternative’ and ‘a pause for consultation’ if things go wrong. The introduction of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) and the CareData makes one nervous that lightning will strike a third time.

Labour has had long enough to think about what could go wrong.

Care professions might feel themselves ill-prepared in person-centred care. A range of training needs, from seasoned physicians to seasoned occupational therapists, will have to get themselves oriented towards the notion of a ‘whole person’. This might involve getting to grips with what a person can do as well as what they can’t do.

The BMA will need to be on board, as well as the Royal Colleges. Doctors, nurses, and all allied health professionals will have to double declutch from the view of people as problem lists, and get themselves into a gear about their patients as individuals who happen to be well or ill at the time.

This needs strong leadership, not people proficient at counting beans such that the combined sum total of a PFI loan interest payments and budget for staff doesn’t send a Trust into deficit.

Nor does it mean hitting a 4 hour target, but missing the point as a Trust does many needless admissions as they haven’t in reality fulfilled their basic admissions assessment fully.

For too long, politicians have been stuck in the groove of ‘efficiency savings’, ‘PFI’, ‘four hour waits’, and become totally disinterested in presenting a person-oriented service which looks after people when they are well as well as when they’re ill.

Once ‘whole person care’ finds its feet, with strong leadership and evident peer-support, we can think about how health is dependent on other parts of society working properly, such as housing and transport.

Technology, if this means that a GP could immediately know what a hospital physician has prescribed in real time in an acute admission, could then be worth every penny.

For the last few years, the discussion has centred around alternative ways of paying for healthcare instead of thinking how best to offer professional care to patients and persons.

The fact that this discussion has been led by non-clinicians is patently obvious to any clinician.

Technology also has the ability to predict, say in thirty years, which of the population is most likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease. Do you really want one of your fellow countrymen to have health insurance premiums at sky high because of having been born with this genetic make-up?

A lot of our problems, like the need for compassion, have been as a result of the 6Cs battling head-on with a 7th C – “cuts”. It’s impossible for our workforce to perform well if they haven’t got the correct tools for the job.

Above all, whole person care needs strong leadership, not just management. And if we get it right the NHS will be less focused on what it’s exporting, but more focused on stuff of real importance.

Building a ‘One Nation Labour Party': the “Collins Review” into Labour Party reform

I’m posting the Collins Review in case anyone wishes to make comments on the document, or simply wishes to read it.

TTIP presents as a crucial test for Labour’s future direction on the NHS

The EU-US (TTIP) trade deal could be worth £67 billion to the EU, and could bring 2 million new jobs to the EU. Here in the UK, it is expected to add between £4 billion and £10 billion a year to our economy. That could mean new jobs for British workers, and stronger, sustainable growth for the British economy. The car industry keeps on bringing up as the poster body for TTIP, but everyone knows there are clear differences.

In Peter Mandelson’s “The Third Man”, Mandelson talks about how his aim was to seek a post-Blair era in leaving a legacy of New Labour. However, he also describes the personal tensions between Blair and Brown. Mandelson felt that there was an inevitability about Labour losing the election in May 2010, but how the mantra “it’s the global economy stupid” might work for Gordon Brown. It didn’t.

The next General Election is due to occur on May 7th 2015. It will be first which Ed Miliband fights. It could also possibly be his last. Miliband is still not ubiquitously popular within his party. If he loses the election, he almost certainly will be ditched by the Party. It would be inconceivable for Ed Miliband to wish to bang on about ‘One Nation’ should the electorate deliver a defeat for his party.

If Ed Miliband loses, there will be a leadership election. Clearly activists, even those who are ambivalent about Ed’s leadership will not wish for anything other than a Labour victory. The chances of a leadership fight, given how time consuming the last one was for Labour, are virtually non-existent. It seems we are ‘nearly there’ with the Labour Policy Review and the Sir John Oldham Commission on ‘whole person care’. It’s unlikely to be as bad as 1983, but who knows. Under Michael Foot, in the 1983 general election Labour had their worst post-war election result.

It is intriguing how much both will have Andy Burnham’s personal stamp on it. Ed Miliband doesn’t wish to commit to the members of his Cabinet, if he were to be elected as Prime Minister. Likewise, there’s a growing feeling that some of the leading candidates, were he to fall on his sword, don’t particularly need his backing. Whether or not Labour can commit to Andy’s hopes would then become irrelevant, unless Andy Burnham becomes a central figure in health after the election. If somebody like Chuka Umunna takes over, what Burnham says now might not matter to an extent.

What Burnham says now can act as a ‘weather vane’ as to the opinions of grasssroots membership of Labour. There has been a growing feeling in this parliament that Labour has acted as a frontman for the corporate establishment. As criticism of monolithic unresponsive outsourcing private providers continues, Ed Miliband may wish to capture on certain elements of left populism, as indeed he did at the Hugo Young Lecture. Miliband has offered to repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012), and has overall made pro-NHS noises.

There’s no doubt that the Tories are scared of Burnham as a potential returning Secretary of State for Health. When David Cameron first addressed Parliament on the Francis Report, he told MPs that he didn’t wish to seek scapegoats. Despite numerous parts of a ‘smear campaign’ from Jeremy Hunt, with one even culminating in a legal threat from Burnham, Burnham has appeared surprisingly resilient. The only explanation of this is that he still carries with him considerable clout within the Labour Party.

The most notable comments by Andy Burnham in George Eaton’s New Statesman interview were on the proposed EU-US free trade agreeement and its implications for the NHS. Many Labour activists and MPs are concerned at how the deal, officially known as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), could give permanent legal backing to the competition-based regime introduced by the coalition.

A key part of the TTIP is ‘harmonisation‘ between EU and US regulation, especially for regulation in the process of being formulated. In Britain, the coalition government’s Health and Social Care Act has been prepared in the same vein – to ‘harmonise’ the UK with the US health system. This would open the floodgates for private healthcare providers well known in the US already. Simon Stevens as the incoming head of the NHS will wish not to appear unduly sympathetic, despite his own background with a US healthcare corporation.

When Eaton spoke to Burnham, he revealed that he will soon travel to Brussels to lobby the EU Commission to exempt the NHS (and healthcare in general) from the agreeement. He said:

I’ve not said it before yet, but it means me arguing strongly in these discussions about the EU-US trade treaty. It means being absolutely explicit that we carry over the designation for health in the Treaty of Rome, we need to say that health can be pulled out.

In my view, the market is not the answer to 21st century healthcare. The demands of 21st century care require integration, markets deliver fragmentation. That’s one intellectual reason why markets are wrong. The second reason is, if you look around the world, market-based systems cost more not less than the NHS. It’s us and New Zealand who both have quite similar planned systems, which sounds a bit old fashioned, but it’s that ability of saying at national level, this goes there, that goes there, we can pay the staff this, we can set these treatment standards, NICE will pay for this but not for this; that brings an inherent efficiency to providing healthcare to an entire population, that N in NHS is its most precious thing. That’s the thing that enables you to control the costs at a national level. And that’s what must be protected at all costs. That’s why I’m really clear that markets are the wrong answer and we’ve got to pull the system out of, to use David Nicholson’s words, ‘morass of competition’.

I’m going to go to Brussels soon and I’m seeking meetings with the commission to say that we want, in the EU-US trade treaty, designation for healthcare so that we can exempt it from contract law, from competition law.

Burnham’s opposition to HS2 was also highly significant.

Now it seems, from a totally unaccountable rumour, that Ed Miliband is to veto a policy by Burnham to hand over control of billions of pounds of NHS funding to local councils. Burnham, outlined proposals last year that would have committed a future Labour government to transfer around £60 billion of NHS money to local authorities to create an integrated health and social-care budget. It appears now that proposals have been rejected by both Miliband and Balls. Both men believe that the policy is misguided and would allow the Tories to accuse Labour of imposing another top-down reorganisation in England. Labour will still attempt to integrate health and social-care budgets to provide “whole person care”, but funding is likely to remain within the NHS.

But it is of course possible that Burnham wants increasingly to not pin his personal fortunes to Ed Miliband, but to what he believes in. And Ed Miliband may not necessarily taking Labour in the direction of a NHS relatively free from a ‘free’ quasi-market.

There are particular concerns about the potential implications of a mechanism called Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS), if it is included in the trade agreement. ISDS allows investors to challenge governments in an international tribunal if the government’s actions threaten their investments. There is concern that this could bypass national courts and limit the ability of democratic governments to enact their own policies. This on top of the EU procurement law fixes the domestic government in a rather tight spot, threatening our national legal and political sovereignty potentially.

There are also particular concerns that the ISDS could apply to the NHS. The Health and Social Care Act (2012), widely held to be a ‘vanity project’ from Andrew Lansley but actually legislated by a neoliberal coalition including the Conservative Party and Liberal (Democrat) Party allows American health care companies to compete for and win NHS contracts. There is a risk that if ISDS was applied to the NHS, repealing the Health and Social Care Act could be deemed to be in breach of the free-trade agreement. This would be a catastrophic legacy for Labour to pick up in May 2015, regardless of whether Burnham is in situ. Of course, many hope dearly he will be Labour’s Secretary of State for Health.

Negotiations are still going on, and Labour will continue to pressure the Government to ensure that the agreement does not place undue limits on future administrations. While Labour are in favour of a transatlantic trade agreement, once a draft agreement is reached, a review will be needed as a matter of some urgency.

What mandate does Miliband seek for his version of the State, and will he deliver?

“Every time I’ve introduced a reform, I wish I’d gone further.”

Tony Blair felt that political opposition to any reform was inevitable. But not even he could have predicted the opposition that faced the Health and Social Care Bill (2011), and the subsequent £2-3 bn top down reorganisation.

The striking thing was that Ed Miliband’s “Hugo Young” speech yesterday did not, in fact, leave you with the impression that his Government “believes in public services”.

Blair felt that his first term in government did not adequately deal with public services. Blair set out his agenda on winning a second term.

“It is a mandate for reform, and an instruction to deliver.”

With the landslide victory of Tony Blair in 2001, Blair believed that Labour “was at his best, when he was at his boldest”. On the other hand, Gordon Brown believed that Labour “was at its best when it is united, best when it is Labour.”

In January 2000, Blair responded to a flu crisis by producing a massive splurge on the NHS. Labour now is obsessed about sticking to the austerity programme, to prove its fiscal credibility. So spending to kickstart yet further reforms of the NHS may not be an immediate option.

The extent to which a Miliband government would be able to deliver a costly set of reforms depends on what his relationship with his Chancellor of the Exchequer is like at the time. At the moment, it can’t be certain that this person will be Ed Balls, who generally positioned himself in the impossible position that the recession would never end.

If Miliband is genuinely concerned about ‘accountability’ for the financially autonomous independent NHS Foundation Trusts, he will have to address how local accountability is in fact lost, in terms of ability to pay for staff and services, if budget sheets are biased by unconscionable interest repayments for PFI.

If Miliband is genuinely concerned about ‘accountability’ for clinical performance, the NHS complaints system and higher regulation must be made fit for purpose. There are concerns about both aspects, and much can be done procedurally to make improvements here.

Ed Miliband wants to be the man to ‘clean up politics’.

It might be procedurally easy to promise and deliver low taxes, if the economy is growing. However, it is an altogether different matter to take to the public that lower taxes might lead to more unaccountable outsourced functions, say in probation or health, where taxes end up subsidising shareholder dividends.

So one of the reforms left to Ed Miliband is public ownership.

It has been argued that bringing NHS services back such that delivered by the State would be prohibitively costly, but not if a Government wishes to maintain excellence in NHS-supplied services and therefore aspires for the NHS to win contracts on an equal playing field basis. At the moment, pitches are won on the slickness of the presentation rather than corporate ongoing performance management.

Miliband may wish the NHS is not political. But it is.

For example, if he wishes primary care to be run by outsourcing companies on behalf of the NHS, there is nothing to stop him legislating for this.

However, on the basis of ‘reforming public services’, it may be a step too far for the ordinary Labour voter.

The argument, that if the time it takes to see your GP is improved, it doesn’t matter who provides your GP services would be the predictable counterargument. It’s this sort of argument which will differentiate Miliband from New Labour – or not.

The paradox is, even if you discount that the greatest legacy of Baroness Thatcher is said to have been New Labour by the lady herself, the centre of gravity has swung away from fragmented, privatised services to a more left-of-centre dialogue.

A gift which has been handed to Miliband on a plate is the failure of the privatised utilities. From that, it has been low hanging fruit to redefine the Markets.

In response to Jeremy Paxman’s question whether Ed Miliband wants a “slimmed down state”, Liz Kendall MP, Shadow Minister for Care Services, offered that Miliband wants a “reformed state”.

Of course, offering unified personal budgets in the form of ‘whole person care’ would be a perfect vehicle for a reformed state. But Labour knows – and ultimately we will know – that it might also be a cover for a ‘slimmed down state’.

Ultimately it’s never been proven that the public actively endorsed the selling off of State assets, like Royal Mail, where there had been some public investment; nor did they ever sign off foreign ownership of previously State infrastructure.

But whilst Labour is in the hock of the City and the hedge funds, rather than the Unions, the reformed State might simply be the Square Mile after all.

What mandate does Miliband seek for his version of the State, and will he deliver?

Ed Miliband: the Hugo Young lecture 2014

It is a huge pleasure to be here with you tonight.

And to be giving the Hugo Young Lecture.

Hugo Young was a figure of great decency and integrity.

He wrote beautifully and insightfully and gave journalism a good name.

As Alan Rusbridger wrote after his death, “Hugo never forgot why he was there: not to make friends or amiably to chew the political cud, but to report and to explain.”

Of the many things that made Hugo Young famous, was the phrase “one of us”.

It was the title he gave to his renowned biography of Margaret Thatcher.

As Hugo began the book:

“Is he one of us? The question became one of the emblematic themes of the Thatcher years.”

“Posed by Mrs Thatcher it defined the test which politicians and other public officials vying for her favour were required to pass.”

Now, I cite this not because I think we should take it as a model for government.

Nor for appointing civil servants.

But in the use of the phrase, Hugo Young was making an important point.

The very fact that Lady Thatcher was able to ask that question meant that she was absolutely clear what she stood for.

Prime Ministers are elected on a manifesto and make policy on that basis.

But in my view whether they achieve lasting change depends not just on specific policies but whether they can define the purpose and mission of their government.

With thousands of decisions taken in government every day, unless there is that sense of purpose, ministers and the people who support them will simply go their own way.

And the whole will be far less than the sum of the parts.

This is particularly true when it comes to the incredibly complex task of running the state and public services.

Over twenty Whitehall departments, more than a hundred local authorities, thousands of hospitals and schools.

Millions of choices are made each year in these organizations.

Even the most hands-on Prime Minister cannot determine those choices—-nor should they want to.

But a Prime Minister and a government can establish a culture for the way public services ought to work.

And the reality is that it doesn’t need civil servants to be ‘one of us’ to respond.

All of my experience is that public servants want a sense of the culture of public service the government wishes to see.

Because this sense of purpose acts as a guide for them.

My aim tonight is to say what that mission would be if I was Prime Minister.

My case is that the time demands a new culture in our public services.

Not old-style, top-down central control, with users as passive recipients of services.

Nor a market-based individualism which says we can simply transplant the principles of the private sector lock, stock and barrel into the public sector.

The time in which we live and the challenges we face demand that we should always be seeking instead to put more power in the hands of patients, parents and all the users of services.

Unaccountable concentrations of power wherever we find them don’t serve the public interest and need to be held to account.

But this is about much more than the individual acting simply as a consumer.

It is about voice as well as choice.

Individuals working together with each other and with those professionals who serve them.

This commitment to people powered public services will be at the heart of the next Labour government and tonight I want to set out why it matters, and what it means in practice.

This vision for public services is rooted in one of the key principles that drive my politics.

The principle of equality.

In his poem, The Prairie Grass Dividing, Walt Whitman talks about what makes for a successful democracy and says it is about a country where people can “look carelessly in the faces of Presidents and Governors, as to say, Who are you?”

Of course, politicians today quite often have that experience.

But not quite in the spirit Walt Whitman meant.

He is expressing the belief that each person however powerful or powerless, matters as much as one another.

An ethical view about the equal worth of every citizen.

This is the foundation of my commitment to equality too.

Whoever you are, wherever you come from, you are of equal worth.

It is the standard I seek to hold myself to as a person.

It means seeking to walk in the shoes of others, not looking over their shoulder to someone more powerful.

And that defines my politics too.

Because from that flows a belief in equal opportunity.

How else can we fulfil our commitment to the equal worth of every citizen?

And from it also flows a belief that large inequalities of income and wealth scar our society and prevent the common life I believe in for our country.

As Benjamin Disraeli wrote in Sybil in 1845 the danger is of “two nations, between whom there is no intercourse and sympathy; who are as ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts and feelings as if they were dwellers in different zones or inhabitants of different planets”.

Those words were true then and feel as true today.

For decades, inequality was off the political agenda.

But nationally and internationally, this is changing.

Many people across every walk of life in Britain – politics, charity and business – now openly say they believe that inequality is deeply damaging.

Internationally too, political and civic leaders are talking about inequality in a way that they haven’t for generations.

At the end of last month, President Obama put it right at the heart of his agenda for government.

A few months before that the Democratic candidate for Mayor of New York, Bill de Blasio, was elected with precisely the same message.

We now have a Pope who says the same.

And that’s because people the world over are beginning to recognise some fundamental facts again.

That it offends people’s basic sense of fairness when the gaps between those at the top and everyone else just keep getting bigger regardless of contribution.

That it holds our economies back when the wages of the majority are squeezed and it weakens our societies when the gaps between the rungs on the ladder of opportunity get wider and wider.

And that our nations are less likely to succeed when they lack that vital sense of common life, as they always must when the very richest live in one world and everyone else a very different one.

I believe that these insights are at the heart of a new wave of progressive politics.

And will be for years to come.

Indeed, not just left of centre politics.

Intelligent Conservatives from David Skelton outside Westminster to Jesse Norman inside recognise the importance of inequality as well.

I believe that the public want to know we get it; we understand the depths of the cost of living crisis they face.

And we can’t go on with countries where the gap between those at the top and everyone else just gets bigger and bigger.

Tackling inequality is the new centre ground of politics.

In the last few years, I have been setting out what that means for Britain.

Of course it is about a progressive tax and benefits system.

But the lesson of the New Labour years is that you can’t tackle inequality without changing our economy, from promoting a living wage, transforming vocational education, to reforming executive pay, to helping create good jobs with decent wages.

I believe that inequality matters in our politics too.

We need to hear the voices of people from all walks of life not just the rich and powerful.

Building a real movement is the best hope of keeping the political conversation grounded in the reality of people’s lives, which so often doesn’t happen at Westminster.

Rooting the Labour Party in every community and every workplace in the country are what my party reforms are about.

Having explained what my beliefs mean for the economy and for politics, today I want to explain what they mean for the state and, in particular, for the way public services work.

For the left and for Labour, public services have always played an essential role in the fight against inequality and poverty.

An essay written in the late 1940s by T. H. Marshall called “Citizenship and Social Class” explained the idea of how public services could act against inequality.

Just as in the 18th and 19th century, civil and political rights had guaranteed a degree of equality, so too social rights would in the 20th.

A free national health service.

Decent state education.

Legal aid.

Pillars of the welfare state and a bulwark against inequality.

For much of the 20th century, politics became a battle about who was best placed to protect and expand this legacy.

For Labour the lesson of all this was a simple one: win power and use the levers of the state to fight against injustice.

That belief endures today.

And understandably so.

But we should never think it does enough on its own to achieve equality.

Because this traditional description of the task of Labour leaves out something fundamental.

I care about inequality of income and opportunity.

But I care about something else as well.

Inequalities of power.

Everyone – not just those at the top – should have the chance to shape their own lives.

I meet as many people frustrated by the unresponsive state as the untamed market: the housing case not dealt with, the special educational needs situation unresolved, the problems on the estate unaddressed.

And the causes of the frustrations are often the same in the private and public sector: unaccountable power with the individual left powerless to act against it.

So just as it is One Nation Labour’s cause to tackle unaccountable power in the private sector, so too in the public sector.

Of course, there is a vibrant and important tradition on the left which takes these inequalities seriously.

More than ever we need to rediscover this tradition.

Michael Young is most famously known as the author of the 1945 Labour manifesto which some saw at the blueprint for a centralized state.

But in 1949 he wrote the book Small Man, Big World which argued that the “large institutions of modern society tend to ignore the interests of ordinary people, who suffer collectively as a result.”

In the 1960s, the New Left and their colleagues also argued for a different kind of state.

The American Saul Alinsky wrote: “self-respect arises only out of people who play an active role in solving their own crises and are not helpless, passive, puppet-like recipients of private or public services.”

And at the same time, feminists were pointing out that women were often especially poorly served by the existing structures of the welfare state.

In my thinking, I have been much influenced by a book written by Richard Sennett, called Respect: The Formation of Character in an Age of Inequality.

He grew up on a Chicago housing estate, and he talks about the interaction between the “professionals” of the welfare state and those who lived there.

And he talked in a memorable phrase about the “compassion that wounds” – well-intentioned, properly motivated, but nevertheless disempowering.

Since then, people like Hilary Cottam have been actively creating new ways of providing public services, moving beyond the old model of delivery.

So the issue of power in public services has always been important.

And it is, in fact, even more urgent today.

For a whole set of reasons.

Because the challenges facing public services are just too complex to deliver in an old-fashioned, top down way without the active engagement of the patient, the pupil or the parent: from mental health, to autism, to care for the elderly, to giving kids the best start in the early years.

Because we live in an age where people’s deference to experts is dramatically waning and their expectations are growing ever higher about having their say.

And because the knowledge and insight that users can bring to a service is even more important when there is less money around to cope with all the demands and challenges.

Clearly the next Labour government will face massive fiscal challenges.

Including having to cut spending.

That is why it is all the more necessary to get every pound of value out of services.

And show we can do more with less.

Including by doing things in a new way.

At the same time, while the challenges are greater for public services than ever before, and make the issue of power all the more urgent, there are greater reasons for optimism too.

Contrary to a 1980s view of self-interested individualism, people by instinct want to help each other.

And that means if we care about giving power away, there will be someone to give it to.

Similarly, technology makes things possible, in ways that simply wouldn’t have been possible in the past.

Big Data, sometimes provided by the public themselves, provides entirely new ways of tackling everything from crime to improving the environment.

And today, the internet means that whether you are a parent, a patient, or a carer you don’t need to be left on your own but can link up with others.

Able to form communities of interest even when people are thousands of miles away.

So the challenge of power is both pressing but also more capable of being solved.

Some people, including the present government, conclude from this challenge that the answer is simple.

Addressing inequalities of power just means crudely importing principles of the private sector into the public sector.

Choice, contestability and competition have a role.

Labour showed in government how the private sector could help to provide extra capacity and speed up hip replacements and cataract surgery for the NHS.

And where existing services have consistently under-performed then alternative providers, including private, third sector or mutuals, are important as a way to turn things around.

But to conclude that market principles are a panacea is simply wrong.

The logic of market fundamentalism is that just like we have a choice over which shop we go to or which cafe, so too we should apply the same to public services.

But it is fairly obvious that this logic is flawed.

Making a decision about which cafe to go to, is something which can be made each time you choose to go out.

It is a completely different story with my son’s school.

If I wasn’t happy with the teaching he was receiving, I shouldn’t have to take him out of the school, disrupting the family, moving him away from his friends.

Even having to set up a school myself.

There should be a mechanism to improve the school.

And this is not the only issue.

Even if we did think market principles were the answer, the resource constraints on government will always limit their effectiveness.

When this government sets up Free Schools in places where there are already surplus places supposedly to create more choice, it does so by taking money away from other kids in real need of a school place.

And we have a looming school places crisis as a result.

Even more problematically, the promised choice often isn’t real.

Replacing one large public sector bureaucracy with a large private sector bureaucracy doesn’t necessarily make the system less frustrating.

Once a government contract for the Work Programme is signed or a train franchise is confirmed, people themselves have no choice over which provider to use because the choice has already been made by the government.

And it turns out that the Serco/G4S state can be as flawed as the centralized state.

Finally, while the creative destruction of the private sector is what powers an economy forward overall, there are other principles that drive public service success.

Like co-operation and care.

If you want to know what can go wrong, just take the government’s decision to import the principles of the privatisation of the utilities in the 1980s into the NHS.

It has meant that hospitals that want to co-operate with each other and integrate are prevented from doing so by an army of competition lawyers who say that’s “collusion”.

The Chief Executive of the NHS himself is saying it is now bogged down in a morass of competition law.

Unable to integrate services which is crucial to improving care and controlling costs.

So while David Cameron promised a Big Society, to unleash the forces of the voluntary sector, he has delivered something rather different.

In some cases, the monolithic private sector replacing a monolithic public sector.

In others, a crude application of market principles which simply hasn’t worked.

And in others still, leaving the unsupported voluntary sector to pick up the pieces where the state has abdicated its responsibility.

It’s no wonder he never uses the phrase Big Society any more.

So what are the principles that should guide us in tackling inequalities of power and improving public services?

What kind of culture would a Labour government seek to encourage?

I want to suggest four principles that will guide what we do.

And these are principles that I hope will be welcomed by millions of public servants who work tirelessly, day in day out, often for low wages, to serve the public.

They often feel that we have a culture that stops them doing their best.

Because the system doesn’t allow them to put those they serve at the heart of what they do.

First, we should change the assumption about who owns access to information because information is power.

And if we care about unequal power, we should care about unequal access to information.

From schools to the NHS to local government, there is an extraordinary amount of information about users of public services.

But the working assumption is still that people only get access to it when the professionals say it is OK or when people make a legal request.

Our assumption should be the opposite.

That information on individuals should be owned by and accessible to the individual, not hoarded by the state.

That people get access to the information unless there is a very good reason for them not to.

As the government has already acknowledged, that must include the right to access your own health records, swiftly and effectively.

But we should go beyond that.

Take education.

Schools collect huge amounts of information on our kids.

The old assumption is that it gets shared with us once or twice a year at a parents’ evening.

But this is a very old fashioned assumption.

As good schools are already showing, there should be continuing access, all year around.

Many good teachers know that its better if parents shouldn’t have to wait for a parents’ evening to understand how their son or daughter is doing, where things are going well and what more they could do.

And new technology makes the sharing of this information much easier.

As at Shireland Collegiate Academy in the West Midlands which provides teachers, pupils and parents real-time information on pupil attainment.

Indeed the Learning Gateway they pioneered is now used by over 100 schools.

And just as with the best private sector companies, we can “track our order”, so too in the public sector we should be able to “track our case”.

Whether it is an application for a parking permit or when you have been a victim of a crime.

Boston, in the United States, pioneered that kind of service a few years ago.

And the Labour council in Birmingham has already created an app for a mobile phone that can do it as well.

We are still in the foothills of what we can achieve for users in the transformation of public services through new technology.

If it can be done by one local council, it should be possible in every government department.

And that’s what we would task the government’s digital service to do.

Guaranteeing for the first time that people get the information they need.

But information is not enough if we are going to tackle the inequalities of power that people face.

My second principle is that no user of public services should be left as an isolated individual, but should be able to link up with others.

The old assumption is that success in public services comes from the professional delivering directly to the single user.

What I have called the “letterbox model”.

Indeed the very term “public service delivery” conjures up this idea of waiting for a service to be delivered by somebody else.

In fact, there is now a wealth of evidence that the quality of people’s social networks with other patients, parents and service users can make a all the difference to the success of the service.

A recent study in the United States found that women suffering with serious illness, with small social networks had a significantly higher risk of mortality than those with large networks.

Support networks made it easier to keep to recommended treatment schedules and, just as important, kept the morale of patients higher.

This is not surprising.

Nothing makes people feel more vulnerable than having to stand on their own.

Confronted with a vast and complex world of services that they can’t make sense of or options they don’t understand.

A friend of mine was telling me just the other day, what it felt like when his son was diagnosed with autism.

And he was battling the local council for proper support.

He and his wife didn’t know what they were meant to do.

They didn’t know what information to trust, or who to believe.

They felt they were standing alone in the world.

What really would have made the difference was being able to talk to other parents in the same position.

That way they could have made sense of the services that were available.

And asked for different teaching methods.

Eventually after years of struggle they managed to do this, but no thanks to the state.

Just as the presumption should be that the user owns and has access to their information, so the presumption should be that service users have the right to be put in touch with others.

Of course, there are already some amazing organisations in Britain that help people do exactly that.

Voluntary groups, for the ill, and the old, for those with kids in local schools, for those battling to look after relatives.

But too often at the moment, rather than helping people come together, the official services feel they’ve been told by people at the centre that their job is not to help put people in touch.

There is often no requirement on them to do so.

It is not part of their training.

Not a central part of what they are expected to do.

We need to change that.

There are already some examples that do precisely this.

In Newcastle, GPs don’t just prescribe drugs to patients, as a norm, they also put patients with chronic or complex conditions directly in touch with others who have the same concerns.

Whether it is diabetes, cancer or Parkinson’s.

The options flash up on the doctor’s computer screen, in exactly the same way the other treatment options do, and they are passed on to the patient.

So no-one has to deal with a long-term condition by themselves.

With the political will, and a small change to the existing information made available to GPs, we could make that possible in every GP’s surgery across our country.

And that is what a Labour government would do.

It is the right thing to do, keeping people healthier and less likely to end up in hospital.

It also means that people have greater power to hold to account a state that is not being responsive.

Some people will fear this.

I think we should embrace it.

Empowering people against the state where necessary.

And we should make it happen in every service that we can.

But if we are truly to make our public services open to the voices of those they are meant to serve, we need to throw the decision making structures open to people too.

We need to tackle inequalities of power at source.

So my third principle is that every user of a public service has something to contribute and the presumption should be that decisions should be made by users and public servants together, and not public servants on their own.

Of course, this is what so many great public services already do.

Personal budgets have allowed many disabled people to shape the services that matter for them, working hand-in-hand with public service professionals.

On a community level, the co-operative council model in Lambeth also shows us the way.

Its services are shaped and controlled directly by the people who they serve, not just by the council staff.

Despite reductions in budgets, services in Lambeth have been improved by this model.

From parks to youth services.

And we should apply this principle more widely.

Take the most difficult decisions that have to be taken in public services, like the restructuring of services in the NHS.

David Cameron used to go round in Opposition saying he would have a moratorium on all hospital changes, that closures would never happen.

He has monumentally broken that promise, including at hospitals he stood outside with a sign opposing change.

Recently the government attempted to close services at Lewisham and downgrade the A and E.

But they failed because they ignored the voice of patients.

Now, instead of learning the lessons, they want to change the law so they can change services across an entire region, bypassing patient consultation.

I am not going to make promises I can’t keep particularly on this issue.

No service can stand still.

But if we truly believe in pushing power down to people, we have to accept that we can’t at the same time defend a system where decisions this important are taken in a high-handed, Whitehall knows best way.

Indeed, the problem with the current approach is that it creates a dynamic of decisions taken behind closed doors, lacking legitimacy, with little public debate about the real reasons a change is being proposed.

Clinicians, managers and patients across the NHS know the system we have isn’t working.

We need to find far better ways of hearing the patient voice.

So a Labour government will ensure that patients are involved right at the outset: understanding why change might be needed, what the options are and making sure everyone round the table knows what patients care about.

No change could be proposed by a Clinical Commissioning Group without patient representatives being involved in drawing up the plan.

Then when change is proposed, it should be an independent body, such as the Health and Wellbeing Board, that is charged with consulting with the local community.

Not, as happens now, the Hospital Trust or Commissioning Group that is seeking the change.

And we will seek to stop and will, if necessary, reverse the attempts by government, to legislate for the Secretary of State to have the power to change services across whole regions without proper consultation.

This is just one example of how we can involve people in the key decisions that affect their lives.

Not saying change will never happen.

But saying no change will happen without people having their say.

We need to do the same in schools.

Having promised to share power, this government has actually centralised power in Whitehall.

Attempting to run thousands of schools from there.

That doesn’t work.

And as a result some schools have been left to fail.

Just last week we saw the Al-Madinah School in Derby close, because its failings were spotted far too late.

Clearly, we need greater local accountability for our schools.

And in the coming months, David Blunkett will be making recommendations to us about how to do this.

As part of that plan, we must also empower parents.

Parents should not have to wait for some other body to intervene if they have serious concerns about how their school is doing, whether it is a free school, academy or local authority school.

But at the moment they do.

In all schools, there should be a “parent call-in”, where a significant number of parents can come together and call for immediate action on standards.

This power exists in parts of the United States.

And I have tasked David Blunkett with saying how that can happen here too.

The fourth principle is that it is right to devolve power down not just to the user but to the local level.

Because the centralized state cannot diagnose and solve every local problem from Whitehall.

And if we are to succeed in devolving powers to users, it is much harder to do that from central government.

It is right that we elect a national government to set key benchmarks for what people can expect in our public services.

That’s part of tackling inequality.

Like how long we have to wait for an operation in the NHS.

What standards of service the police should provide.

And to ensure that the teachers in our classrooms possess a proper qualification.

But how specific services are delivered within these standards and guarantees cannot simply be dictated from Whitehall.

For the last year, as part of Labour’s Policy Review led by Jon Cruddas, our local innovation taskforce comprising outstanding council leaders from Manchester, Hackney and Stevenage has been looking at how we can deliver more with less.

And Andrew Adonis has been leading work on city regions, and their potential to drive our future prosperity if we devolve budgets and power down.

The conclusions of both these important pieces of work will be published in the coming months.

And as we prepare for a Labour government the on-going Zero-Based Review across all of public spending, being led by Ed Balls and Chris Leslie has these ideas at its core.

This work is clear that by hoarding power and decision-making at the centre, we end up with duplication and waste in public services.

As well as failing to serve people, particularly those with the most complex problems.

That is why the next Labour manifesto will commit to a radical reshaping of services so that local communities can come together and make the decisions that matter to them.

Driving innovation by rethinking services on the basis of the places they serve not the silos people work in.

Social care, crime and justice, and how we engage with the small number of families that receive literally hundreds of interventions from public services.

And so too in the coming months, across the major public services, we will be showing how we can improve genuine local accountability.

In addition to the Blunkett Review in education, the Institute of Public Policy Research’s Condition of Britain project is doing important work here.

John Oldham will also be reporting on how we can fulfil the vision of “whole person” care, better co-ordinating mental health, physical health and social care by devolving power down.

And following the Stevens Review on policing, Yvette Cooper will be coming forward with recommendations on how we can bring decisions on neighbourhood policing closer to local people.

In all of these public services, we are determined to drive power down.

This devolution of power is the right thing to do for the users of public service and is the right way to show that we can do more with less.

When I set out on the journey of becoming Leader of the Opposition nearly three and half years ago, I knew the most important thing was to do the hard thinking about the condition of Britain and what needed to change.

As Hugo Young knew, ideas and hard intellectual thinking are the most under-rated commodities in British politics.

To be a successful Opposition, you need to be able to tell the country what’s wrong and how it can be changed.

And to be a successful government, you need a defining mission.

Hugo Young and I didn’t agree with Lady Thatcher on most things.

But I suspect he would have agreed with her on this: “Politics is more when you have convictions than a matter of multiple manoeuvrings to get you through the problems of the day.”

Over the last few months, whether it is on energy or banking or on 50p tax, Labour has prompted debate and indeed criticism.

I relish that debate and believe strongly that the criticism just comes with the territory.

It is what happens when you make the political running.

I know that we are putting the right issues at the heart of our programme.

And we are standing where the British people stand.

They want a government that will stand up for them against unaccountable power, wherever it is.

They want more control over their own lives.

I am determined that is what the next Labour government will do.

That is the culture of the government I want to lead when it comes to public services.

Tackling inequality in income, opportunity and power.

That will be Labour’s mission in 2015.

Andy Burnham MP’s speech in Birmingham on the state of the NHS

Thank you all for coming today.

It’s a sign of how much we value the NHS that you have taken time to come along this morning.

In February 2012, the battle over the Government’s proposed reorganisation was reaching its peak.

There were claims and counter-claims about what it would all mean.

Now, two years on, it’s time to assess what has happened in the two years since and the overall state of the NHS today as we head towards a General Election which will determine its future.

My conclusion is this: the NHS has never been in a more dangerous position than it is right now, and the evidence for that is the relentless pressure in A&E.

The last 12 months have been the worst year in at least a decade in A&E with almost a million people waiting more than four hours.

A&E is the barometer of the whole health and care system and it is telling us that this is a system in distress with severe storms ahead.

A reorganisation which knocked the NHS to the floor, depleted its reserves, has been followed by a brutal campaign of running it down.

It looks to many that the NHS is being softened up for privatisation which, all along, was the real purpose of the reorganisation.

Things can’t go on like this. It’s time to raise the alarm about what is happening to the NHS and build a campaign for change.

The tragedy is that the Government can’t say they weren’t warned.

Even at the eleventh hour, doctors, nurses, midwives and health workers from across the NHS were lining up in their thousands and pleading with the Prime Minister to call off his reorganisation.

Why?

Because they could see the danger of throwing everything up in the air in the midst of the biggest financial challenge in the history of the NHS.

But David Cameron would not listen. He ploughed on regardless.

It was a cavalier act of supreme arrogance.

As the dust settles on this biggest-ever reorganisation, the damage it has done is becoming clear.

The NHS in 2014 is demoralised, degraded and confused.

The last two years have been two lost years of drift.

Even now, people are unsure who is responsible for what.

Two years of drift when the NHS needed clarity.

And what was it all for?

The Government hasn’t even achieved its supposed main goal of putting doctors in charge.

CCGs are not the powerhouse we were promised.

Instead, the NHS is even more ‘top-down’ than it was before, with an all-powerful NHS England calling the shots.

Just look at Lewisham.

When local GPs opposed plans to downgrade their hospital, the Secretary of State fought them all the way to the High Court.

So much for letting GPs decide.

Now the Secretary of State wants sweeping powers to close any hospital in the land without local support. Labour will oppose him all the way.

And the specific warnings Labour made ahead of the reorganisation have come to pass.

First, we said it would lead to a loss of focus on finance and a waste of NHS resources.

An outrageous £3 billion and counting has been siphoned out of the front-line to pay for back-office restructuring – £1.4 billion of it on redundancies alone.

Just as we warned, thousands of people have been sacked and rehired – 3,200 to be precise.

One manager given a pay-off of £370,000 – and last week we learn he never actually left the health service.

It is a scandalous waste of money and simply not justifiable when almost one in three NHS trusts in England are predicting an end-of-year deficit.

Cameron promised he would not cut the NHS but that is precisely what is happening across the country as trusts now struggle to balance the books.

2,300 six-figure pay outs for managers; P45s for thousands of nurses – that’s the NHS under Cameron.

What clearer sign could there be of a Government with its NHS priorities all wrong?

Second, Labour warned that the reorganisation would result in a postcode lottery.

Last week, a poll of GPs found that seven out of 10 believe rationing of care has increased since the reorganisation.

NICE has warned that patients are no longer receiving the drugs they are entitled to and has even taken the unusual step of urging them to speak up.

New arbitrary, cost-based restrictions have been introduced on essential treatments such as knee, hip and cataract operations – leaving thousands of older people struggling to cope.

Some are having to pay for treatments that are free elsewhere to people with the same need.

Cameron’s reorganisation has corroded the N in NHS – again, just as we warned.

Third, we warned that rhetoric about putting GPs in charge was a smokescreen and the Act was a Trojan horse for competition and privatisation.

Can anyone now seriously dispute that?

Last year, for the first time ever, the Competition Commission intervened in the NHS to block collaboration between two hospitals looking to improve services.

How did it come to this, when competition lawyers, not GPs, are the real decision-makers?

The NHS Chief Executive has complained that the NHS is now “bogged down in a morass of competition law”.

Since April, CCGs have spent £5 million on external competition lawyers as services are forced out to tender.

And it will come as no surprise that, since April, seven out of 10 NHS contracts have gone to the private sector.

Who gave this Prime Minister permission to put our NHS up for sale, something which Margaret Thatcher never dared?

The truth is that this competition regime is a barrier to the service changes that the NHS needs to make to meet the financial challenge.

It is sheer madness to say to hospitals that they can’t collaborate or work with GPs and social care to improve care for older people because it’s “anti-competitive”.

If we are to relieve the intense pressure on A&E, and rise to the financial challenge, it is precisely this kind of collaboration that the NHS needs.

So the summary is this – the NHS has been laid low by the debilitating effects of reorganisation, has been distracted from front-line challenges and is now unable to make the changes it needs to make. It is a service on the wrong path, a fast-track to fragmentation and marketisation.

It lost focus at a crucial moment – and is now struggling to catch up.

The evidence of all this can been seen in the sustained pressure in A&E – the barometer of the NHS.

The price we are all paying for the Prime Minister’s folly is a seemingly permanent A&E crisis.

Hospital A&Es have now missed the Government’s own A&E target in 44 out of the last 52 weeks.

This is unprecedented in living NHS memory – a winter and spring A&E crisis was followed by a summer and autumn crisis. The pressure has never abated.

The reorganisation has contributed very directly to this A&E crisis.

Three years ago, the College of Emergency Medicine were warning about a growing recruitment crisis in A&E but felt like “John the Baptist crying in the wilderness” as Ministers were obsessing on their structural reform.

The very organisations that could have done something about it – strategic health authorities – were being disbanded. Just when forward planning was needed, we saw cuts to training posts.

All this leaves us with an A&E crisis which gets worse and worse.

Of the one million people who went to a hospital A&E this January, 75,000 waited longer than 4 hours to be seen.

Of the 300,000 people admitted to hospital after going to A&E, 17,500 had to wait between 4 and 12 hours on a trolley before they were admitted.

On one day in January, 20 patients were left on trolleys for over 12 hours.

In the last year, ambulances have been stuck in queues outside A&E 16,000 times – leading to longer ambulance response times.

On 92 occasions, A&E departments had to divert ambulances to neighbouring hospitals because they were so busy.

And now the pressure from the A&E crisis is rippling through the system.

In January, over 4,500 planned operations were cancelled – causing huge anxiety for the people affected.

The waiting list for operations was the highest for a November in six years.

The truth is that the Government have failed to get the A&E crisis under control and it is threatening to drag down the rest of the NHS.

They have desperately tried to blame the last Government’s GP contract – it’s never their fault, of course – but the facts shows an exponential increase in A&E attendance since 2010.

In the last three years of the Labour Government, attendances at A&E increased by 16,000.

In the first three years of this Government, attendances increased by 633,000. No wonder we have an A&E crisis.

The question we need to ask is: why, behind the destabilising effect of reorganisation, has there been such an increase?

I see three reasons – all policy decisions taken by David Cameron.

First, David Cameron has made it harder to see your GP.

He scrapped Labour’s guarantee of an appointment within 48 hours.

Now, the story I hear up and down the country is of people phoning the surgery at 9am only to be told there is nothing available for days.

The Patients Association say that it will soon be the norm to wait a week or longer to see your GP.

What will they do? Go to where the lights are on – A&E.

We have called on the Government to reverse their scrapping of the 48-hr target this winter.

The problem is made worse by the scrapping of Labour’s extended opening hours scheme.

Now hundreds fewer GP surgeries stay open in the evening and at weekends – taking us backwards from the seven day NHS we need.

To make matters worse, a quarter of Walk-In Centres have closed and NHS Direct has been dismantled.

A terrible act of vandalism even by this Government’s standards – nurses replaced by call-handlers and computers that say ‘go to A&E’.

The second reason for the sudden increase in people attending A&E is cuts to social care and mental health.

Under this Government, almost £2 billion has been taken out of budgets for adult social care.

Compared to a decade ago, half a million fewer older people are getting support to help them cope.

We have an appalling race to the bottom on standards with 15-minute slots, minimum wage pay, zero hours contracts.

Over-stretched care workers, often not paid for the travel time between 15 minute visits, having to decide between feeding people or helping them wash.

Social care in England is on the verge of collapse – and yet last year Jeremy Hunt handed back a £2.2bn under-spend to the Treasury.

That’s unforgiveable when care is being taken away from vulnerable people.

If Labour were in Government now, we would be using the NHS underspend to tackle the care crisis this year.

Instead, older people are being allowed to drift towards A&E in record numbers – often the worst possible place for them.

A recent Care Quality Commission report found avoidable emergency admissions for pensioners topping half a million for the first time – and rising faster than the increase in the ageing population.

Terrible for older people, putting huge pressure on A&Es and costing around a billion pounds a year.

But other vulnerable people are suffering too.

The Government is cutting mental health more deeply than the rest of the NHS.

Some mental health trusts are now reporting bed occupancy levels of over 100%.

That means more than one patient being allocated to the same bed.

It’s no wonder we’ve heard growing evidence of highly vulnerable people being held in police cells or ending up in A&E because no crisis beds are available.

Under this Government, A&E has become the last resort for vulnerable people

And this brings me to the third reason for the pressure on A&E – the cost-of-living crisis.

As Michael Marmot set out in his seminal public health report, our health isn’t just about our health services, but the kind of society in which we choose to live.

No phenomenon more clearly symbolises the true impact of this Government than the rise of food banks, teachers having to feed hungry children at school or GPs having to ask their patients if they can afford to eat.

And all this while millionaires get a tax cut.

We have seen diseases of malnutrition like scurvy and rickets on the rise – diseases we once thought had gone for good.

Today we are exposing another scandal that goes right to the heart of whose side this Government is on.

People are struggling to keep warm in their homes.

The average energy bill has risen by more than £300 since 2010 – while the support for people in fuel poverty has been cut considerably.

The Government replaced 3 successful Labour schemes- warm front, community energy saving programme and carbon emissions reduction target with their ECO scheme.

And the consequence is that just a fraction of households have received help in the past year, just when the support is most needed.

I don’t see how it can be right that money from all of our energy bills should subsidise people who can afford to improve their properties, over those people in dire fuel poverty.

We’ve seen record levels of hypothermia reported this year.

Since the election there has been a dramatic increase in the number of older people admitted to hospital for cold-related illnesses.

There have been 145,000 more occasions when over-75s had to be treated in hospital for respiratory or circulatory diseases than in 09/10.

This is the human cost of this Government’s cost-of-living crisis and their failure to stand up to the energy companies.

And why Labour’s energy bill freeze cannot come a moment too soon.

In conclusion, this is the fragile state of the NHS and the country after almost four years of Tory-led Coalition.

The country can’t go on like this – the NHS needs a different Government.

Cameron’s Government has delivered it a brutal double whammy.

First they knocked it down the NHS down with a reorganisation no-one wanted. Then they have spent the last year running it down at every opportunity.

They are guilty of the gross mismanagement of the NHS.

But it is not just incompetence. They are running it down for a purpose.

Only yesterday, the head of the independent regulator attacked the NHS and called for more privatisation.

This was an astonishing intervention at a time when politicisation of regulators is so high in the news.

To have the independent regulator making such a political statement means there can no longer be any doubt – more privatisation is the explicit aim of this Government’s NHS policy.

Labour believes this will break up the NHS and bring fragmentation when what the NHS desperately needs is permission to integrate and collaborate.

That is why this Wednesday we will force a debate in the Commons on the A&E crisis and repealing the Government’s competition regime.

This is the choice the country faces – a public, integrated NHS under Labour or a health market under David Cameron.

That’s the ground on which we will fight in 2015 and, for our NHS, it’s crucial that we win.

After New Labour, does Russell Brand have a point?

“It’s not up to Tony Blair to rename my party to ‘New Labour'”.

And thus spake Tony Benn.

With nearly 10 million “hits”, it’s beyond reasonable doubt that the interview between Jeremy Paxman and Russell Brand has been an internet viral sensation. It’s appreciated that, despite successes as the national minimum wage, Blair’s government was ideologically of ‘no fixed abode’, and the “clause 4 moment” can be interpreted as a symbol of the rejection of socialism (akin to Hugh Gaitskell).

Jeremy Paxman himself has said publicly that he is not particularly drawn by any political party, and about three and a half years ago the popular Labour blogger, Sunny Hundal, started an initiative to recapture “a million lost votes”.

At around the time, Peter Kellner did a tour of the conferences circuit explaining how people had curiously become detached from “the political process”. The backdrop to this is that the political process produces one leg of the ‘One Labour tripos’, the other two legs being the ‘one nation economy’ and ‘one nation society’.

Various cogent explanations were offered for this ‘democratic deficit’ in England, but curiously not high on the list was the finding that this Coalition kept on introducing statutory instruments which had not been clearly signposted in either of their two manifestos (sic). One glaring example, apart from tuition fees of course, is the Health and Social Care Act (2012).

There is no doubt that Russell Brand’s viewpoint, whilst appearing somewhat self-exhibitionist, is potentially very engaging. However, Brand’s conclusion of not bothering voting appears at first blush to be completely at odds with what Tony Benn has been arguing for ages. That’s if you don’t factor in the possibility of a Lib-Lab coalition, with our unamended boundary changes.

Tony Benn is of course not the font of all knowledge, but he is an incredibly wise man whom is the target of much affection by modern day socialists. Benn has long argued that ‘democratic socialists’ often cannot buy influence by donating lots of money to multinational corporates, but they can exert influence their democratic vote. Rather than being Brand’s ‘lost cause’ or spoilt ballot paper, in Benn’s Brave New World a vote means hope.

And indeed logically any vote against decades of English policy designed to transfer resources from the State to the shareholder dividends of private limited companies and plcs, otherwise known as “privatisation”, fits the bill.

Also, if it’s the case that the Lobbying Bill has a parliamentary intention of strangling at birth trade union activity rather than the private sector companies wishing to ‘rent seek’ in a new liberalised NHS, Benn’s desire for us socialists to exercise our vote could not have come at a better time.

The question is of course: which party should I vote for which has the best chances of delivering a NHS based on reciprocity, solidarity, equality, cooperation, collaboration and social justice (otherwise known as socialism)? There’s an argument that true “believers” of the NHS might vote Labour (as the party which implemented the NHS under Clement Attlee’s Prime Ministership with Aneurin Bevan as health minister).

You could ‘hold your nose’ and vote Labour, as Professor Ray Tallis put it at the book launch of ‘SOS NHS’ at the Owl Bookshop in Kentish Town, or you could, on the other hand vote for one of the other alternatives, Greens or NHS Action Party. At the end of the day Benn, I’m sure, would endorse the idea that you should produce a vote most likely to produce your preferred option in the real world? But which party represents best how you feel?