Home » Information Technology (Page 2)

I would like to propose a SHA committee on the use of GP data in the NHS

The GP-patient consultation is a pivotal part of everyday activity of the NHS. Whilst the reasons that a patient may decide to go to see his or her GP are diverse, it is clear that much information is exchanged in that consultation. Some of that information will be relevant for deciding upon the need for further investigations and examination, and even possible referral to other parts of the NHS. The data might therefore very useful at an individual level. However, the data, taken as a whole for a population, might also produce useful insights which are relevant for further research, and are therefore enormously beneficial for public health.

The GP-patient consultation is a pivotal part of everyday activity of the NHS. Whilst the reasons that a patient may decide to go to see his or her GP are diverse, it is clear that much information is exchanged in that consultation. Some of that information will be relevant for deciding upon the need for further investigations and examination, and even possible referral to other parts of the NHS. The data might therefore very useful at an individual level. However, the data, taken as a whole for a population, might also produce useful insights which are relevant for further research, and are therefore enormously beneficial for public health.

When a patient goes to see his/her own GP, normally the patient has an expectation that the consultation will be confidential. This is at the crux of the doctor-patient relationship.

1. Medical confidential data from an individual perspective

From April 1st 2013 there was a noteworthy change to the way in which the Department of Health collected information about patient health from GP record systems in England. Previously, mainly aggregate health data was collected and patients could sometimes opt out of having identifiable information from their own record uploaded to central systems. From April 1st, the newly-renamed NHS “Health and Social Care Information Centre” (HSCIC) began uploading identifiable patient information, without telling patients how they can opt out of this process – or even that they can. The data uploaded included every patient’s NHS number, date of birth, postcode and ethnicity, together with details of medical conditions, diagnoses and treatments.

That information is held on HSCIC and other NHS systems where it will be used to analyse health trends and demand for services, improve treatment and provide evidence upon which local clinical commissioning groups can base decisions about service provision. The data will also be made available to outside parties such as researchers and for-profit companies, and this is where the concern that “data will be sold to the highest bidder” has emerged from in the recent media (see for example the Guardian, “£140 buys private firms data on NHS patients”, article by Randeep Ramesh @tianran 17 May 2013). The HSCIC say that it will be ‘anonymised’ before release, but the concept of anonymisation is highly controversial and it is unlikely that guarantees can be given about the possible re-identification of the data.

2. Medical confidential data from a population perspective

However, there is also a parallel consideration, which could be seen as a fundamental socialist goal of solidarity. Patient records in general practice surgeries constitute a unique resource that can provide evidence to help medical researchers improve their understanding of disease, develop potential new treatments and improve patient care. But patient information is both sensitive and private, and the security of personal data must be safeguarded. The Wellcome Trust in 2009 argued that Research has shown that the public are generally supportive of research. Two-thirds of people are likely or certain to allow ‘personal health information’ to be allowed for research – however, there is little public understanding of what this actually means in practice.

As such, the Wellcome Trust therefore believed it was imperative to improve engagement and awareness among the general public:

- there should be a national awareness-raising programme highlighting the importance of using patient records for research, describing the difference between identifiable and non-identifiable data, and explaining the safeguards that will be put in place to protect privacy

- information should also be provided locally through general practices, for example as patients register at a practice, and through posters and leaflets.

The Wellcome Trust argued that, “transparency is essential, and it should be clear that patients can opt out of the use of their identifiable information in research if they wish.” For example, there may be times when it might be useful to know how agents of the NHS themselves behave in making decisions, for example to what extent GPs comply with NICE guidance, and to look for any reasonable deviation from ‘best practice’.

There is a plethora of approaches which could be taken to a ‘train of enquiry’ in how information has handled at GP level. The aim of this Committee is not to go on a ‘fishing expedition’ about all the uses of information at a GP level, for example incentives in making clinical decisions or ‘Nudge’.

The aim of this proposed Committee, for which applications from any interested parties are invited, including from General Practice, academics, doctors in other specialties (especially public health), and patients themselves, is to consider primarily whether patients in the NHS are aware of their ‘rights’ about the information they provide into the NHS, and how the needs for patient confidentiality at an individual and population level can be reconciled from the perspectives of the patient, the researcher, and other interested parties.

Members of the Committee ideally would therefore have to keep themselves familiar with recent policy developments which are relevant, including NHS information governance (including NHS England) and the views of the research councils (including the Wellcome Trust), as well as be aware of the approximate direction of travel of the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) and EU Data Protection Regulation. It would also be useful if members of the Committee are aware of the current activities of campaigning groups such as Medical Confidential or Liberty, who have tried to raise awareness of this issue previously, and continue to work for the pursuit of that goal.

Thanking you in anticipation.

Useful background reading

http://medconfidential.org/briefings/

http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/About-us/policy/Spotlight-issues/personal-information/gp-records/index.htm

£140 buys private firms data on NHS patients: http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2013/may/17/private-firms-data-hospital-patients (Randeep Ramesh, 17 May 2013, Guardian – @tianran)

GP patient data boosts research: http://www.gponline.com/News/article/1014146/GP-patient-data-boost-research/

Shami Chakrabarti, Director of Liberty, is ‘absolutely stunned’ at the GP Extractor Scheme, questioning its legality

The Court of Public Opinion can be as important as any Court of Law.

“Human rights are about holding the powerful to account“. Lest there be any doubt: Shami Chakrabarti, Director of Liberty, is fiercely critical on the lawfulness of personal patient data derived from GPs without the consent of patients. Shami explained that privacy is a fundamental human right, “without privacy, there can be no dignity, no intimacy, and, in this context, there can be no trust”. Chakrabarti argued that trust is fundamental to the operation of the public good in running a healthcare.

Chakrabarti criticised that there was no parliamentary debate about the General Practice Extraction Service, which would be a problem if this matter went to Strasbourg. She commented:

“This new policy on GP data extraction is what I have real concerns about from a human rights perspective. The domestic courts have not been vigilant. I personally find it difficult, at first blush, how it can be necessary, proportionate and legality for this extraction mechanism which seems to remove ownership from the patient, and which seems to expose these sensitive records with real exposure to loss. We have seen this umpteen times with big databases. My colleagues are dubious about any legal basis for this even in domestic law. Even if you say you can justify this, you need to have had a proper parliamentary debate about this aspect of policy, not just the Health and Social Care Act in general.”

“Some of this information is to be passed to non-NHS bodies. I am absolutely stunned at this, I think there is a real opportunity to challenge this in the Court of Public Opinion and the European Court of Human Rights under the Human Rights Act and the European Convention of Human Rights.”

Chakrabarti was the “star turn” in a one-day conference, hosted by @MedConfidential (led by Phil Booth, @EinsteinsAttic) which I enjoyed very much in Dean Street, Soho today.

In England, there exists a general common law duty imposed on health professionals to respect the confidences of their patients. A requirement to maintain confidentiality of patient confidentiality is also maintained in the professional codes of conduct. This limits the conditions for which patient data can be used for research. Confidentiality is not, of course, an absolute principle. There is no breach of confidentiality if the patient consents to their information being shared. The doctrine of consent is therefore a pivotal consideration.

The NHS is not of course new to any controversy about data management. On 29 March 2012, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency and the Department of Health’s National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) launched the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD).The Clinical Practice Research Datalink is designed to provide researchers with access to safeguarded data that respects patient confidentiality. This will give valuable insights into serious health conditions and ultimately help reduce the time it takes to develop new treatments. The Clinical Practice Research Datalink website provides the following information (click here):

“The Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) is the new English NHS observational data and interventional research service, jointly funded by the NHS National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). CPRD services are designed to maximise the way anonymised NHS clinical data can be linked to enable many types of observational research and deliver research outputs that are beneficial to improving and safeguarding public health.” Ian Brown from the Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University, Lindsey Brown from the School of Social and Community Medicine at the University of Bristol, and Douwe Korff

London Metropolitan University, published an interesting article entitled “Using NHS Patient Data for Research Without Consent” in December 2010, in Law, Innovation and Technology (Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 219-258) (link here).

Can patients object to their personal data being included? “Up to a point, Lord Copper”, but the paper sets out the following:

“Objectors’ records can accordingly be marked in a tab in the system as ‘Consent refused for GPRD Data Collection’, if patients are ‘adamant that they do not want their records to be included in the scheme’. According to the Guide, this ensures that their medical records will not form part of the draw-down of records for inclusion in the GPRD. The [Guide for GP Practice Managers] Guide repeatedly suggests that patients in participating GP practices have given their ‘consent’ for the extraction of their data to the system, presumably because they are assumed to have seen the poster and did not opt out of the system. That is a highly dubious assertion… Here, we may note that it is also doubtful whether many patients are actually even aware of their GP practices’ participation in the scheme.”

It is widely recognised that medical research does not benefit the individual patient directly the data concerns. It is quite easy to demonstrate that research carried out by other NHS employees, academic researchers or pharmaceutical companies do not fall within patient care. There may be benefits of this research to the patient or his/her family, but it can be easily argued that patients ought to be given a choice as to whether they wish their information to be used for such purposes. Consent should therefore be obtained in such an argument. Even with sharing of information is deemed to be ‘in the public interest’, it has been considered fair and lawful for patients to be involved in decisions about the release of identifiable information to third parties.

However, I’m pretty certain that European Convention of Human Rights law will ‘kick in’, however the above is ultimately resolved. Article 8, a right to private and family life, is a typical ‘human right’, in that it must serve a ‘legitimate purpose’, must be ‘necessary’ and must be ‘proportionate’ in relation to its purpose. The situation above, many would argue, is compatible with human rights law, even considering the purported usefulness of such a measure. The EC Directive on Data Protection is directly relevant here, and particularly the concept of “personal data”.

Opinion 4/2007 on the concept of personal data is very helpful (link here). On page 13, it provides:

“In cases where prima facie the extent of the identifiers available does not allow anyone to single out a particular person, that person might still be “identifiable” because that information combined with other pieces of information (whether the latter is retained by the data controller or not) will allow the individual to be distinguished from others. This is where the Directive comes in with “one or more factors specific to his physical, physiological, mental, economic, cultural or social identity”.

Some of the “best bits” are as follows:

11.30 Online patient records: safety and privacy – Ross Anderson, Professor of Security Engineering at the University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory

12.40 NHS Confidentially and Patient Advice – Helen Wilkinson, Coordinator of TheBigOptOut Patient Advice Line

“The Big Opt Out” link is here.

Your medical confidentiality is at risk from this new database, as over a million NHS employees and central government bureaucrats will have access to not only your medical records but also your demographic details name, address, NHS Number, GP details, phone number (even if it’s ex-directory) and mobile number.

There is no opt out whatsoever for your demographic details. You can only have them hidden in special circumstances if the police or social services request it if, for example, you are a celebrity or on a witness protection scheme. Many public and private sector workers will otherwise have access to your address and phone number, from social workers to pharmacists.

You will eventually be allowed to ‘lock down’ some of your medical details (though the security mechanisms haven’t been built yet). But although you can keep some of your medical details confidential from some of the doctors involved in your care, they can override this if they think it’s necessary, and there is no way for you to keep your information confidential from civil servants. You will no longer be able to attend any Sexual Health or GUM (Genito-Urinary Medicine) Clinic anonymously as all these details will also be held on this national database, alongside your medical records. For the first time everyone’s most up-to-date and confidential details are to be held on one massive database.

Click here for more information, here for the latest news, and here to find out what you can do about it.

16.10 Our right to medical privacy – Shami Chakrabarti, Director of Liberty

We have to wait until the end of a ‘fixed term parliament’ to bring this, and other issues such as the newly enacted section 75 regulations of the Health and Social Care Act, to the Court of Public Opinion. However, a legal challenge could be much sooner than that.

The EU Data Protection Regulation: dual challenges for proportionality in primary care and for research

According to today’s Health Services Journal, the new Caldicott Review will recommend a new duty of sharing of medical data where it is in the patients’ best interests:

“The Caldicott review into information governance in health and social care is likely to recommend a new duty to share information between agencies where it is in a patient’s best interests. In an exclusive interview with HSJ Dame Fiona Caldicott, who has been leading the review for the past year, said the six information governance principles she formulated in 1997 were still relevant today. Her previous review led to the introduction of “Caldicott guardians” responsible for data security in each organisation. However, she said her current review would propose two modifications to the rules. “We’ve suggested a new principle which is about the duty to share information in the interests of the patients’ and clients’ care,” Dame Fiona said. The move would balance a tendency towards caution over sensitive information, even where sharing it between health or care providers could lead to better care, she said.”

Sir David Nicholson yesterday conceded that he found it odd that he could be sitting around a board meeting table, and the Chief Nursing Officer of a particular trust would be regulated by his or her regulatory body, the Chief Medical Officer would be regulated likewise by his or her regulatory body, but the manager would not be professionally regulated by any body. However, as a mechanism of last resort perhaps, nobody is above the law. As described here, on 25 January 2012, the Commission published its proposal for a new ‘General Data Protection Regulation’. The proposed Regulation promises greater harmonisation – but at the price of a significantly harsher regime, requiring more action by organisations and with tough penalties of up to 2% of worldwide turnover for the most serious data protection breaches. The draft Regulation is even longer than the current Directive (95/46/EC), running to 118 pages and 139 Recitals. The draft is to be finalised by 2014 and is planned to enter into force a further 2 years after that finalised text is published in the Official Journal. This Regulation is to have powerful effects on domestic policy regarding medical data sharing for research and for medical care. Whilst the legal doctrine of proportionality governs both policy issues, they have the potential to cause unhelpful confusion.

The European doctrine of proportionality means that, ‘an official measure must not have any greater effect on private interests than is necessary for the attainment of its objective’:Konninlijke Scholton-Honig v Hoofproduktchap voor Akkerbouwprodukten [1978] ECR 1991, 2003. Exactly how the courts should approach issues of proportionality was discussed by Lord Steyn in the case of R (Daly) v SSHD [2001] 2 WLR 1622, in which he said at paragraph 27: “The contours of the principle of proportionality are familiar. In de akeitas v Permanent Secretary of Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Lands and Housing [1999] 1 AC 69 the Privy Council adopted a three-stage test. Lord Clyde observed, at p 80, that in determining whether a limitation (by an act, rule or decision) is arbitrary or excessive the court should ask itself: “whether: (i) the legislative objective is sufficiently important to justify limiting a fundamental right; (ii) the measures designed to meet the legislative objective are rationally connected to it; and (iii) the means used to impair the right or freedom are no more than is necessary to accomplish the objective.”

The response by the European Public Health Association to the report by the European Parliament’s Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs report on the proposal for a General DataProtection Regulation (2012/0011(COD)) sets out the formidable nature of this challenge.

“The European Public Health Association, representing 41 national public health associations with over 14,000 members, welcomes the proposal by the European Commission to propose a Data Protection Regulation (2012/0011(COD) that seeks to create a proportionate mechanism for protecting privacy, while enabling health research to continue. In particular, the clarity provided by these proposals will make it possible for high quality research that will benefit their citizens to be undertaken in some Member States where this has not previously been the case. However, we view with the utmost concern the amendments set out by the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs of the European Parliament in their report dated 16.1.2013. These amendments would mean that:

- Data concerning health could only be processed for research with the specific, informed and explicit consent of the data subject (amendments 27, 327 and 334-336)

- Member States could pass a law permitting the use of pseudonymised data concerning health without consent, but only in cases of “exceptionally high public interest” (amendments 328 and 337)

- Pseudonymised data would be considered within the scope of the Regulation, even where the person or organisation handling the data does not have the key enabling reidentification (amendments 14, 84 and 85)

The consequences of these amendments for health research would be disastrous, a description that we do not use lightly. If implemented, they would prevent a broad range of health research such as that which has contributed to the saving of the lives of very many European citizens in recent decades. We are concerned that these amendments must reflect a misunderstanding of the nature of health research and the central role played by data in undertaking it, and in particular our evolving understanding of the crucial importance of obtaining unbiased and representative data on large populations so as to minimise the risk of reaching incorrect conclusions that could potentially lead to considerable harm to patients.”

And indeed the authors of that letter, Professor Walter Ricciardi (President) and Prof Martin McKee (President-Elect) [at the time of writing of that letter 21 February 2012], concluded:

“We understand the need to strike an appropriate balance between the societal need for research that can promote the health of Europe’s citizens and the mechanisms that ensure the safe and secure use of patient data in health research and the rights and interests of individuals, while noting that they themselves have an interest in being able to benefit from treatment based on research. We believe that the Commission’s proposals achieve this balance but that the proposed amendments do not and, if passed, they would have profoundly damaging implications for the future health of Europe’s citizens.”

This has been followed up with the following, taken from “The ESHG suppports an initiative of the EUPHA: “EU Data Protection Regulation has serious impact on health research” (dated 7 February 2013):

“A number of these have serious implications for health research, based on the rapporteur’s premise that “processing of sensitive data for historical, statistical and scientific research purposes is not as urgent or compelling as public health or social protection.” He gives no indication of how the evidence for urgent action for public health or social protection purposes might be obtained without research. Were the amendments to pass, the major concern is that they would mean that identifiable health data about an individual could never be used without their consent. This would mean that much important epidemiological research could not take place. For example, it would outlaw any registry-based research, such as that using cancer or disease registers. This would also make it virtually impossible to recruit subjects with particular conditions for clinical trials. The amendments would allow Member State to pass a law permitting the use of pseudonymised/key-coded data without consent, but only in cases of “exceptionally high public interest”. (Amendment 27, p24; Amendments 327 and 328, p194-195; Amendments 334-337, p198-200.) this would be an impossibly high bar for all but the most exceptional research, such as that on bioterrorism. In addition, the amendments would bring all pseudonymised/key-coded data within the scope of the Regulation, even where the person or organisation handling the data does not have the key. This would significantly increase the regulatory burden on organisations using pseudonynmised data or sharing these data with collaborators in countries outside the EU. (Amendments 13 and 14, p15-16; Amendments 84 and 85, p63-64). This would have implications not only for the soon to be 28 Member States but also for accession states implementing the acquis communitare and for those in other countries collaborating with EU researchers.”

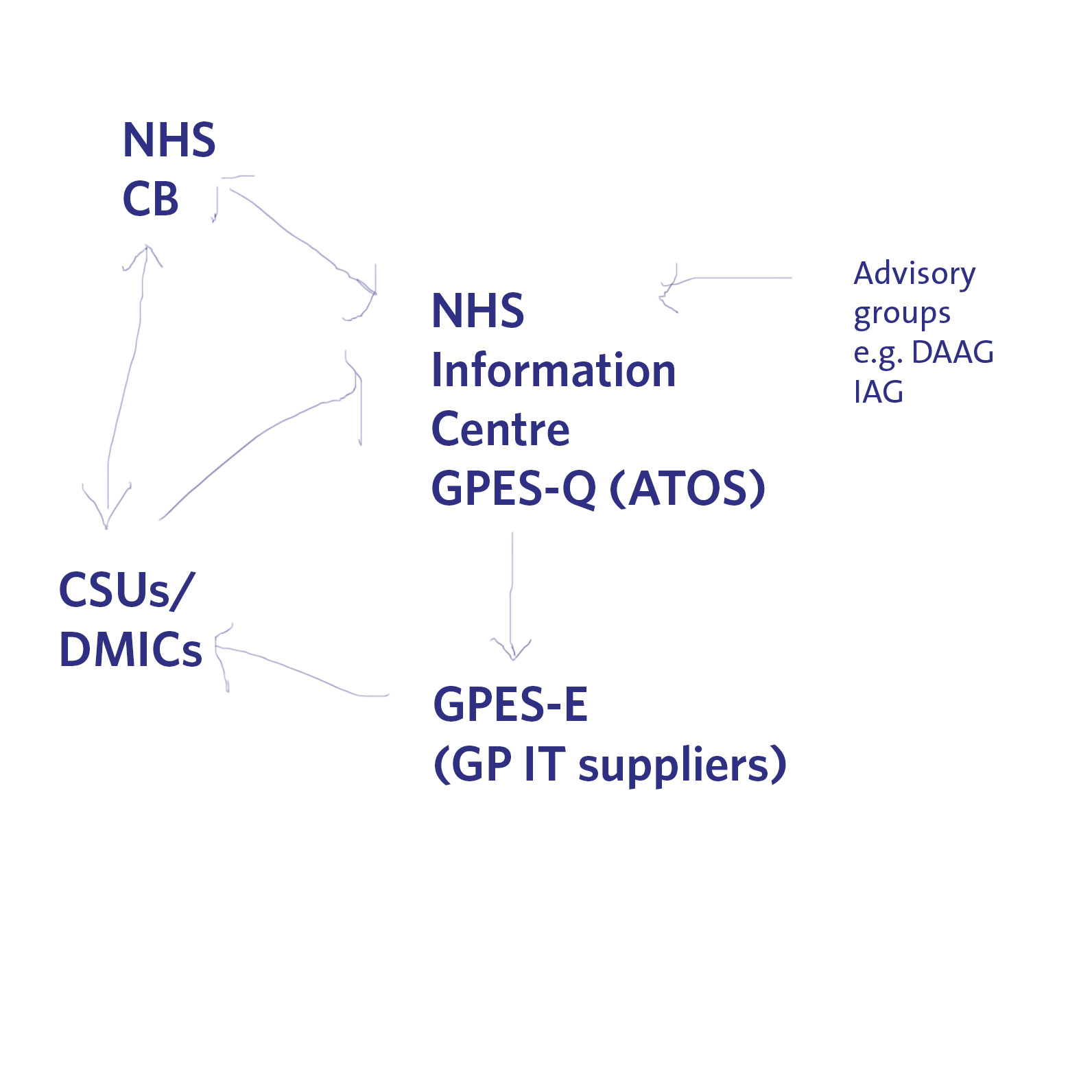

Indeed, there is another big problem looming on the horizon for data sharing of medical information. Currently ATOS is running a service which allows queries to be made of GP data (“GP extraction service”), with the main GP IT “system suppliers” providing the hardware for this to be possible in GP surgeries. The information can then be made available to DMICs (formerly the “CSUs”), and it is currently unclear how the DMIC will be processing this information legally in compliance with the Data Protection Act [1998], and the rôle of the NHS Commissioning Board in “requiring” information from the system. A very basic description of this new scheme is shown pictorially below.

The expectation is, nonetheless, that these medical data have commercial value to industry, pharma, social marketing companies, management consultancies in health, etc. as “big data”. It is argued that the prospect of commercial sale of medical data is part of the justification for government expenditure on GP data and the drive towards “integration”. Already, there is growing recognition for the need for clinical regulators to keep a careful eye on potential drifting of confidential information under the guise of ‘presumed consent’, not genuine informed consent. There is arguably a material risk that any public outcry over commercial sale of patients’ data without consent, or any major mishap in commercial handling of personal health data, may lead to justification for clamours to support the EU proposals and subsequent legislation.

However, the legal doctrine of proportionality might come back to haunt the keeping of these data somewhere in the system. In a famous unanimous judgment, S and Marper v UK (2008), delivered 4 December 2008, the European Court of Human Rights found that the retention of the applicants’ fingerprints, cellular samples and DNA profiles was in violation of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights – the right to respect for private and family life. Again, this case fundamentally rested on the legal doctrine of proportionality (full judgment here); as discussed elsewhere, the Court recognised the state had a legitimate aim in retaining DNA and fingerprints. The Court then examined whether retention was necessary in a democratic society. Certainly, the door is ajar to a test case being taken later down the line whether the GP extraction scheme is unlawful given article 8 considerations, and organisations such as Liberty may then be the most unlikelist of campaigners for patient confidentiality in reality.

These are complicated issues, but the framework for the extraction of GP data and their use, and the use of information for research in public health, appears to be the EU Data Protection Regulation. That is why it is important to get the implementation right in our domestic policy, otherwise there will be test cases brought in front of Europe in due course. Whatever the knee-jerk reaction politically to Europe and the whole issue of human rights, it is most unlikely that we will leave Europe as all three major parties have triangulated themselves into a position of being pro-EU. However, whilst the details of these discussions might be taking place behind closed doors amongst key stakeholders, they will need to be aired one day.

Don’t you think it’s very odd a Conservative PM should nationalise something? What is the real issue about patient records?

Even Google gave up on their central database for health information called “Google Health”. Whilst few things are as certain as death and taxes, it is fairly certain that there is big money in big data. Lord Shutt of Greetland, Chair of the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust Ltd. warned, in a foreword on a recent report on “the database state”, that the problem is huge, and as a society we must face up to formidable challenges. There has always been a tough balance in the law between balancing individual rights of privacy and freedom, with the State’s rights of national policy of health and security, for example. Whatever ideological position the Liberal Democrats eventually settle on, it is striking that a Conservative Prime Minister should actually advocate nationalising something.

It is unsurprising that Big Pharma would have welcomed the move. Andrew Witty, the chief executive of GlaxoSmithKline, stated to the Sunday Telegraph he welcomed the data-sharing initiative: “Any action the government takes to improve the environment in this country for life science across these activities is welcome.” The Autumn Statement (2011) had indeed signposted this. It might seem paradoxical that the Department of Health at this time wishes to embark on an initiative to make the NHS “paperless”, at a time when a reorganisation, estimated at £3bn, is currently underway. Patient data, essential for individual patient security, confidentiality and consent, are “rich pickings” for the private healthcare industry, which have not collectively paid to collect this information nor invest in the IT infrastructure of the NHS, but the ethical concerns are enormous. Personalised medicine, dependent on real-time patient information, is “the next big thing” emergency in the pharmaceutical industry, currently keeping stocks of companies very healthy. However, the professional code for Doctors, from the General Medical Council (“GMC”) is very clear on the regulation of patient confidentiality and privacy: this is contained within “Confidentiality” (2009), and clearly guides doctors on the conflicting balance between confidentiality and disclosure.

There are interesting reasons why the operational roll-out of the National Patient Record failed in 2006-7. It is now reported that all prescriptions, diagnoses, operations and test results will be uploaded on to central computers by the end of next year, and, by 2018, all NHS organisations will be expected to be able to share this information with other hospitals, GPs, ambulances and health trusts. Mr Hunt hopes local councils will sign up to similar systems, along with private care homes. As with the overall direction of travel of the NHS towards an insurance system where private companies pay “a greater part”, this blurring of the need for patient consent has been insidious.

Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 (originally enacted under Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001), allows the common law duty of confidentiality to be set aside in specific circumstances where anonymised information is not sufficient and where patient consent is not practicable. For example a research study may require access to patient identifiable data to allow linkages between different datasets where the cohort is too large for consent. This would require time limited access to identifiable information where gaining consent from a large retrospective cohort would not be feasible and would require more identifiable data than would be necessary for linkage purposes. However, section 10 of the Data Protection Act (1988) currently allows a right for an individual to prevent damage or distress by data processing. This is indeed conveniently “triggered” by section 259(10) of the Health and Social Care Act (2010), i.e. “[the provision] is subject to any express restriction on disclosure imposed by or under another Act (other than any restriction which allows disclosure if authorised by or under an Act”:

The Secondary Uses Service (SUS) Programme supports the NHS and its partners by providing a single source of comprehensive data for planning, commissioning, management, research, audit, public health and “payment-by-results”, a reimbursement mechanism for acute care payments. It is critical to know whether patients their right to opt out of the SUS database. It should not be the case that NHS patients are denied hospital care if they do not agree to my records being sent to SUS. Steve Nowottny in his “Editor’s Blog” for Pulse, a newspaper circulated to GPs, on 8 January 2013 outlined some important very recent developments:

“That year, Pulse ran a ‘Common Sense on IT’ campaign which highlighted a series of concerns over the consent and confidentiality safeguards in the new system.

“GPs wanted patients to have to give explicit rather than merely implied consent before records were created. Plans to use data within the records for research purposes without explicit consent had Catholic and Muslim leaders up in arms, because they feared the research could be purposes contrary to their faiths, such as abortion or stem cell research.

We revealed that celebrities, politicians and other patients whose information is regarded as sensitive would be exempted from the automatic creation of a Summary Care Record, raising questions about the system’s security. And we reported that patients who did not initially choose to opt out of the Summary Care Record would be unable to have their records subsequently deleted.

At the time, it felt as though the stories, while interesting and concerning, were somewhat theoretical. The Summary Care Record’s deployment to date had been patchy and it was far from certain it would continue. In the meantime, fewer than 1% of patients had bothered to opt out. (Now, with nearly 22 million records created and more than 41 million patients contacted, the figure stands at 1.34%).

But the news today that 4,201 patients had Summary Care Records created without them giving even implied consent – and that they will not be able to have them deleted – reignites the whole debate. Suddenly ‘what if’ scenarios have become reality.”

Tim Kelsey is the NCB’s National Director for Patients and Information – his stated aims are to put transparency and public participation at the centre of a transformation of customer service in the NHS. In a recent lecture, he quoted George Soros who said “our social institutions are imperfect, they should be open to improvement [and that] requires transparency and data“. On-line banking and e-ticketing demonstrate the power of open access to personal data in a safe, secure way – for some reason, heath data is deemed more personal that finance and travel arrangements. Data.gov.uk is an example of his vision for the future – the UK has so much medical data, not only about patients but also genomics and other bioinformatics disciplines. The law currently gives the NCB power to mandate more data flows – TK targets April 2014 to get outcomes-based data flows from primary and secondary care – once achieved, next step is to embrace social and specialist care. So, once the data is “freely available”, it can be made available for public participation – he is investing in a course called ‘Code for Health’, a 3 day course to learn how to develop apps. Data is essential from April 2013, there will be push for on-line interaction with GPs, to realise nationally the benefits seen in pilot areas.

So why should commissioners need access to “personal identifiable data”. It is considered that these may be “good reasons”:

- integrated care and monitoring services including outcomes & experience requires linkages across sources

- commissioning the right services for the right people requires the validation that patients belong to CCGs and have received the correct treatments

- aspects of service planning and monitoring on geographic data basis require postcodes for certain type of analysis

- understanding population and monitoring inequalities

- target support for patients and population groups at highest risk requires data from several sources linked together

- specialist commissioning is commissioned outside local areas and can require wider discussions about individual patients and their associated costs

- ensuring appropriate clinical service delivery and process requires access to records

To enable commissioning, ‘personal identifiable data’ including NHS no, DOB, Postcode data needs to flow to “data management integration centres” (“DMICs”). The DMICs need to have similar powers and controls to the Health and Social Care Act information centres to process data In order for processing of PID at DMICs to be undertaken legally, a change in legislation will be required; it is considered that legislative changes can not be achieved by April 2013, and that the new Caldicott is report expected around Jan/Feb 2013. Meanwhile, DMICs need to be operational in April 2013.

David Cameron has stated explicitly his intention for social care to head towards a private insurance system. As stated in the transcript of the interview with Andrew Marr,

“Well the point that was being made earlier on the sofa by Nick Watt, this is a massive problem – that you know more and more people suffering from dementia and other conditions where they go into long-term care and there are catastrophic costs that lead them to have to sell their homes to pay for that care – it’s right to try and put in place a cap which will then open up an enormous insurance market, so people can insure against that sort of catastrophic loss.”

A longrunning conundrum about where there is such intense interest in ‘raising awareness of dementia’. The idea of having GPs and physicians ‘diagnose’ dementia on the basis of a screening test, without it being called ‘screening’ in name, has not been backed up with the appropriate resource allocation for dementia care elsewhere in the system, including adequate training for junior doctors and nurses crucially involved in actual dementia care. Is this and integration of care an entirely virtuous sociological problem? Integration of care at first sight seems to involve primarily avoidance of reduplication of operations, and better ‘coordinated’ care between health and social care and funding. This is not an unworthy ambition at all. It is well known that the endpoint of the Pirie and Butler “Health of Nations” blueprint for NHS privatisation has a greater rôle for the private insurance market as the endpoint, so it makes complete sense to have a fully integrated IT system which private insurers and the Big Pharma can tap into. Lawyers will, of course, be cognisant about the added beauty of integration of clinical and financial information. One of the biggest banes of insurance markets is information asymmetry, making calculation of risk and potential payouts difficult. Insurers will argue that calculation of risk is only possible with precise information, and as I described earlier, clinical commissioning groups are merely “statutory insurance schemes”. It is a long-held belief that private insurers refuse to pay off given the slightest lack of compliance in terms and conditions, but private insurers provide that this mechanism needs to exist to protect them making unnecessary payouts. Failure to disclose medical conditions is an excellent way for private insurers to get out of “paying up”, otherwise known as rescission.

So, given all the above, you can see why the current Government wish to progress with this particular approach to private medical data. The private insurance market and Big Pharma stand to benefit massively, and their lobbying is much more sophisticated than lobbying from GPs, physicians or members of the public. The drive towards all nurses having #ipad3s and all TTOs from Foundation Doctors being sent by broadband to nursing homes may seem utterly virtuous, but there are more significant drivers to this agenda beyond reasonable doubt.